Unraveling Tourist Behavioral Intentions in Historic Urban Built Environment: The Mediating Role of Perceived Value via SOR Model in Macau’s Heritage Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do different dimensions of environmental stimuli affect tourists’ perceived value in a historic urban setting?

- (2)

- How does perceived value mediate the relationship between environmental stimuli and behavioral intentions?

- (3)

- Which types of environmental stimuli are most effective in fostering desirable tourist behaviors?

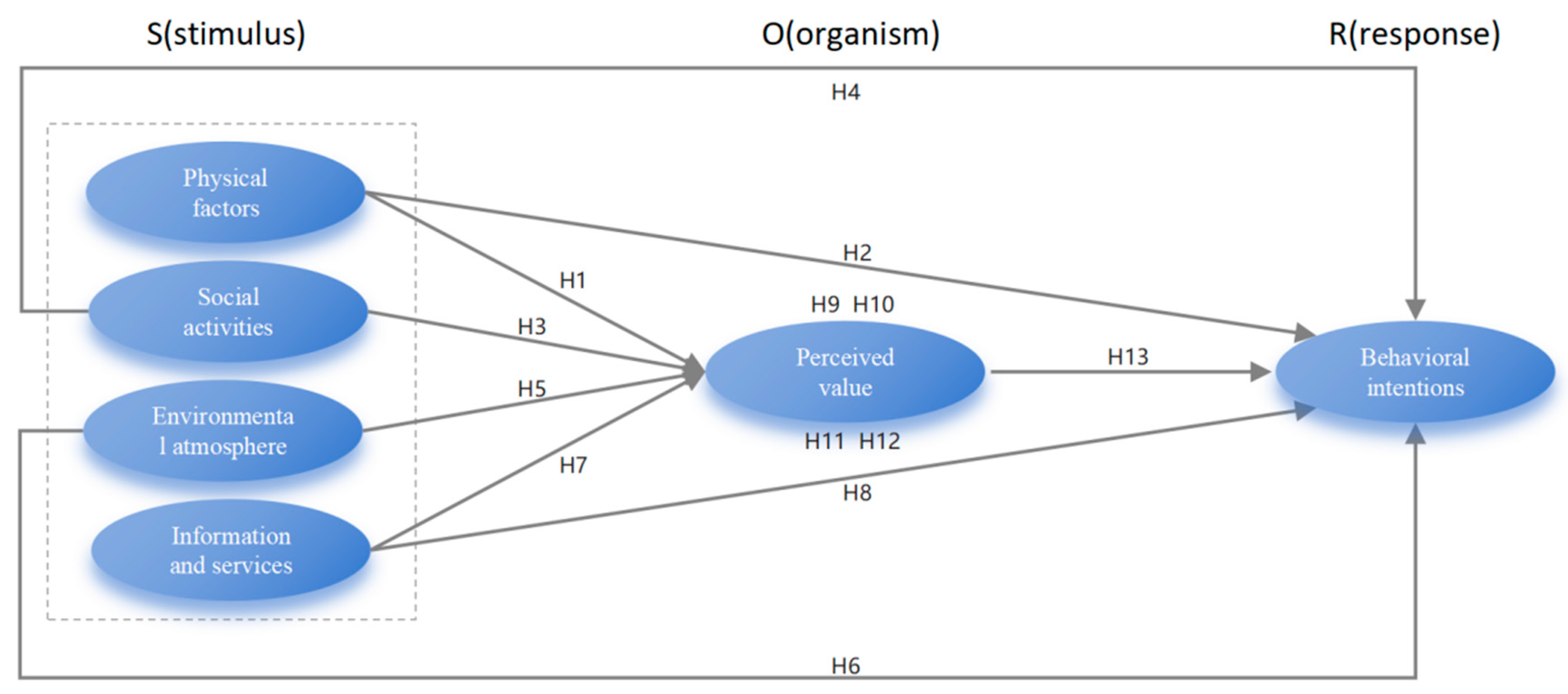

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory

2.2. Perceived Value

2.3. Conceptual Framework

2.4. Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Object

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Collection

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Model Fit

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.4. Mediating Effect Test

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Significance

5.2. Practical Significance

5.3. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horlacher, P. Tourists Go Home: Stakeholder Attitudes in the Face of Overtourism the case of Dubrovnik, Croatia. In ISCONTOUR 2024 Tourism Research Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Student Conference in Tourism Research; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2024; p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Daily Overseas Edition. Macau Polishes its Cultural Tourism Brand. The State Council Information Office of China. Available online: https://www.zlb.gov.cn (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Luo, W.; Wang, L. Safeguarding the cultural roots in urban and rural development. Guangxi Daily, 7 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, A.; Mohino, I.; Moya-Gómez, B. Using Flickr geotagged photos to estimate visitor trajectories in world heritage cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Timothy, D.J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: Cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W. Extending the theory of planned behavior with the self-congruity theory to predict tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions: A two-case study of heritage tourism. Land 2022, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rêgo, C.S.; Almeida, J. A framework to analyse conflicts between residents and tourists: The case of a historic neighbourhood in Lisbon, Portugal. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, M.A.; Alnaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E. The heritage jewel of Saudi Arabia: A descriptive analysis of the heritage management and development activities in the at-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, Ö.; Karaman, A. A participatory planning model in the context of Historic Urban Landscape: The case of Kyrenia’s Historic Port Area. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Noonan, D.S. The price of preserving neighborhoods: The unequal impacts of historic district designation. Econ. Dev. Q. 2020, 34, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Wong, Y.D. The multivalent nexus of redevelopment and heritage conservation: A mixed-methods study of the site-level public consultation of urban development in Macao. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Annunziata, A.; Yamu, C. The multi-method tool “PAST” for evaluating cultural routes in historical cities: Evidence from Cagliari, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqadam, S.; Nubani, L. The impact of spatial changes of Shiraz’s historic district on perceived anti-social behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareti, S.; Henche, B.G. Association practices in historical districts as facilitators of destination brand image. The case of las letras Distric, Madrid & Italia District, Santiago of Chile. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2021, 79, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jayantha, W.M.; Yung, E.H.K. Effect of revitalisation of historic buildings on retail shop values in urban renewal: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.E.; Lee, J.R. The impact of historic building preservation in urban economics: Focusing on accommodation prices in Jeonju Hanok Village, South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.M.; Silva, S.; Carvalho, A. Economic valuation of urban parks with historical importance: The case of Quinta do Castelo, Portugal. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X. Development of a Phenomenological Evaluation Model for the Dark Tourism Experience in the Mem-Oral Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Chosun University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 2022, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Pandita, S.; Mishra, H.G.; Chib, S. Psychological impact of COVID-19 crises on students through the lens of stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodworth, R.S. Psychology, 2nd ed.; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Vonoga, A. Trends of consumer purchases via social media according to the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. Dev. 2021, 1, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. A verbal measure of information rate for studies in environmental psychology. Environ. Behav. 1974, 6, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Garrod, B.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Seyfi, S.; Cifci, I.; Vo-Thanh, T. Antecedents of memorable heritage tourism experiences: An application of stimuli–organism–response theory. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, R.; Li, W.; Xiong, M. Stimulating tourists’ senses for sustainable destination development: Combining embodied cognition theory and the SOR model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 13567667241289611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X. Stimulus-organism-response framework: Is the perceived outstanding universal value attractiveness of tourists beneficial to world heritage site conservation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandža Bajs, I. Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The example of the Croatian tourist destination Dubrovnik. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, M.H. Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: Involvement as a moderator. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Castañeda-García, J.A.; Del Barrio-García, S. Self-congruity and motivations as antecedents of destination perceived value: The moderating effect of previous experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Park, K.S.; Wei, Y. An extended stimulus-organism-response model of Hanfu experience in cultural heritage tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 30, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. How visitors perceive heritage value—A quantitative study on visitors’ perceived value and satisfaction of architectural heritage through SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Chen, T.; Liu, J. Research on the evaluation model of tourism destination image perception bias. Tour. Trib. 2009, 24, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Liang, Y.W.; Lin, W.R. Conceptualization and measurement of the recreationist-environment fit. J. Leis. Res. 2012, 44, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, L. A study of the influence of environmental stimuli on behavioral intentions in the tourism experience of memorial spaces. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Seebaluck, V.N.; Naidoo, P. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Case of Mauritius. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 904–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. Research on the Behavior and Influencing Factors of Rural Tourists. Master’s Thesis, Ningxia University, Ningxia, China, 2023, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Cui, C.; Ma, C.; Guan, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Research on community relations, benefit perception, and pro-tourism behavior: A moderated mediation model. Arid Land Geogr. 2020, 43, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, M. The Influence of the Atmosphere of Religious Landscape ‘Emei’ on Tourists’ Perceived Value. Doctoral Dissertation, Siam University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2023, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Ma, S.; Li, Y. The impact of the cultural atmosphere of overseas Chinese hometowns on tourists’ behavioral intentions—The moderating role of cultural contact. J. Huaqiao Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 45, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. Research on the Relationship Between the Cultural Atmosphere of Scenic Spot Names and Tourists’ Behavior Intentions. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China, 2019, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Shen, C.W. The correlation analysis between the service quality of intelligent library and the behavioral intention of users. Electron. Libr. 2020, 38, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Shu, M. The impact of digital service scenarios in urban ecological parks on tourists’ behavioral intentions. J. Zhejiang Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Research on the Impact of Gym Environment and Perceived Value on Fitness Enthusiasts’ Continuous Consumption Intention. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China, 2023, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsios, F.; Mitsopoulou, E.; Moustaka, E.; Kamariotou, M. User-Generated Content behavior and digital tourism services: A SEM-neural network model for information trust in social networking sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X. Research on the impact of social support on tourism behavior intention in the era of the internet economy—Mediated by perceived value. Econ. Res. Guide 2023, 15, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haji, S.A.; Surachman, S.; Ratnawati, K.; Rahayu, M. The effect of experience quality on behavioral intention to an island destination: The mediating role of perceived value and happiness. Accounting 2021, 7, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Lu, C.C. Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, I.; Unusan, C.; Cobanoglu, C. Service Quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on behavioral intention in restaurants: An integrated structural model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tourism 2021, 22, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Cristovao Verissimo, J.M.; de Oliveira, J.C.L. Memorable tourism experiences, perceived value dimensions and behavioral intentions: A demographic segmentation approach. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1472–1486. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, R.E.; Tinsley, M. Athletics versus academics? Evidence from SAT scores. J. Pol. Econ. 1987, 95, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A.; Rhemtulla, M. Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling: A discussion and tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 4, 2515245920918253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Cheng, X. Formation mechanism of heritage responsibility behaviour of tourists in cultural heritage cities from the perspective of affective-cognitive evaluation. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1278–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Leou, C.H. A study of tourism motivation, perceived value and destination loyalty for Macao cultural and heritage tourists. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shang, H. Service Quality, perceived value, and citizens’ continuous-use intention regarding e-government: Empirical evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ziadat, M.T. Applications of planned behavior theory (TPB) in Jordanian tourism. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Fyall, A. Destination service quality, affective image and revisit intention: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. Macau Inbound Tourists in 2024 and December 2024. Available online: https://mo.mofcom.gov.cn/tjsj/amjjsj/art/2025/art_1734d1fc9b644974bc86063a35a52ff1.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J.; Liu, H. Testing procedure and application of mediation effect. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, H.; Collins, J.R. How Commercialized Festivals Affect the Transmission of Traditional Religious Rituals: A Case Study of the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto. Art Soc. 2024, 3, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Reisinger, Y.; Ahmad, M.S.; Park, Y.N.; Kang, C.W. The influence of Hanok experience on tourists’ attitude and behavioral intention: An interplay between experiences and a Value-Attitude-Behavior model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šegota, T. Two Faces of the Adriatic Pearl: The Leader in Overtourism and Sustainability. In Tourism Interventions; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon, J.P.; Barrieau, N.; Beale, A.; Bourgeois, D.; Gannon, D.; Cohnstaedt, J.; Dutil, P.A.; Harvey, F.; Jeanotte, M.S.; Marontat, J.; et al. Cultural Policy: Origins, Evolution, and Implementation in Canada’s Provinces and Territories; University of Ottawa Press: Otawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadin, I.M.; Gjurašić, M.; Krešić, D. From over-tourism to under-tourism—An opportunity for tourism transformation in the City of Dubrovnik. In Ethical and Responsible Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhuele, N.; Vanneste, D. How Significant Are Buffer Zones for Tourism at Urban UNESCO World Heritage Sites? Heritage 2025, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, H.; Marzano, M.; Cruz, A.R.; Elston, J.N. Overtourism and Short-Term Rental Effects in Florence and Lisbon: The Perspective of Residents’ Associations. In Short-Term Rentals and Their Impact on Destinations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 201–236. [Google Scholar]

- Derke, F.; Filipović-Grčić, L.; Raguž, M.; Lasić, S.; Orešković, D.; Demarin, V. Neuroaesthetics: How we like what we like. In Mind, Brain and Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, A.; Ward, J. Eye-tracking Boston City Hall to better understand human perception and the architectural experience. New Des. Ideas 2019, 3, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles, D.H.; Boak, J. Bonding with beauty: The connection between facial patterns, design and our well-being. In Urban Experience and Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy, M.; Salingaros, N.A. Design for a Living Planet: Settlement, Science, & the Human Future; Sustasis Press: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lavdas, A.; Sussman, A.; Woodworth, M. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Neuroscience and the Built Environment, Routledge: London, UK, 2025; in press. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Handbook-of-Neuroscience-and-the-Built-Environment/Lavdas-Sussman-Woodworth/p/book/9781032744216 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

| Variable | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Physical factors | A1: The historic urban area has abundant natural landscape resources. | Liu et al. (2023) [36]; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al. (2015) [37]; Cai and Cheng (2024) [55] |

| A2: The historic urban area has multiple historical and cultural buildings. | ||

| A3: The historic urban area has a well-developed infrastructure. | ||

| A4: The historic urban area has abundant cultural relic resources. | ||

| Social activities | B1: The historic urban area provides diverse recreational activities. | Liu et al. (2023) [36]; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al. (2015) [37]; Wu and Li (2017) [38]; Wang and Leou (2017) [56] |

| B2: The historic urban area provides various types of cultural exchanges. | ||

| B3: The historic urban area regularly hosts cultural activities, such as folk ceremonies, festive celebrations, and performances. | ||

| B4: The historic urban area blends harmoniously with the daily life of local residents. | ||

| Environmental atmosphere | C1: The signs at the historic urban area are esthetically appealing and blend seamlessly into the overall environment. | Liu et al. (2023) [36]; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al. (2015) [37] |

| C2: The background music and lighting design of the historic urban area create a strong scenario-specific atmosphere. | ||

| C3: A strong historic and cultural atmosphere is created around the historic urban area through the use of color, decorations, and cultural symbols. | ||

| C4: The historic urban area is clean, hygienic, and comfortable in general. | ||

| Information and services | D1: The historic urban area provides convenient information guidance. | Liu et al. (2023) [36]; Wu and Li (2017) [38]; Li and Shang (2020) [57] |

| D2: The historic urban area provides various information media. | ||

| D3: The historic urban area provides comprehensive information and services for tourists. | ||

| D4: The service personnel of the historic urban area behave with proper etiquette. | ||

| Perceived value | E1: Visiting the historic urban area is highly beneficial (as I gain more experience and knowledge). | Pandža Bajs (2015) [28]; Wu and Li (2017) [38] |

| E2: Visiting the historic urban area is pleasant. | ||

| E3: Spending time and money touring the historic urban area is worthwhile. | ||

| Behavioral intentions | F1: I will share my experience of this trip with others. | Wu and Li (2017) [38]; Kolar and Zabkar (2010) [58]; Al Ziadat (2015) [59]; Tosun et al. (2015) [60] |

| F2: I would recommend the historic urban area to others af-ter this trip. | ||

| F3: I will revisit the historic urban area when the opportuni-ty arises. |

| Category | Statistical Indicator | Sample Size | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 141 | 51.27 |

| Male | 134 | 48.73 | |

| Age group | Under 18 | 19 | 6.91 |

| 18–24 | 78 | 28.36 | |

| 25–34 | 24 | 8.73 | |

| 35–44 | 81 | 29.45 | |

| 45–60 | 29 | 10.55 | |

| Over 60 | 44 | 16.00 | |

| Number of Visits to This Place | Three or more times | 54 | 19.64 |

| Within three times | 93 | 33.81 | |

| The first time | 128 | 46.55 | |

| Mode of Travel | With partner | 50 | 18.18 |

| With family | 89 | 32.36 | |

| With friends | 58 | 21.10 | |

| Travel agency package | 22 | 8.00 | |

| Alone | 56 | 20.36 | |

| Source of Information About This Place | TV | 36 | 13.09 |

| Travel agency | 30 | 10.91 | |

| Tourist brochure | 16 | 5.82 | |

| Magazine | 17 | 6.18 | |

| Network | 95 | 34.55 | |

| Friends and family recommendations | 67 | 24.36 | |

| Other | 14 | 5.09 | |

| Education Level | Junior high school and below | 8 | 2.91 |

| High school or technical school | 25 | 9.09 | |

| Associate college | 22 | 8.00 | |

| Undergraduate | 145 | 52.73 | |

| Master’s and above | 75 | 27.27 | |

| Occupation | Professional technical personnel | 51 | 18.55 |

| Institution staff | 32 | 11.64 | |

| Business executives (including private business owners) | 49 | 17.82 | |

| Company staff | 34 | 12.36 | |

| Students | 22 | 8.00 | |

| Housewives | 15 | 5.45 | |

| Retired personnel | 28 | 10.18 | |

| Freelancers | 36 | 13.09 | |

| Other | 8 | 2.91 | |

| Average Monthly Income | 3000 and below | 23 | 8.36 |

| 3000–4999 | 41 | 14.91 | |

| 5000–6999 | 49 | 17.82 | |

| 7000–8999 | 32 | 11.64 | |

| 9000–10,000 | 52 | 18.91 | |

| 10,000 and above | 78 | 28.36 |

| Variable | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha | Common Factor Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical factors | A1: The historic urban area has abundant natural landscape resources. | 0.891 | 0.761 |

| A2: The historic urban area has multiple historical and cultural buildings. | 0.723 | ||

| A3: The historic urban area has a well-developed infrastructure. | 0.805 | ||

| A4: The historic urban area has abundant cultural relic resources. | 0.787 | ||

| Social activities | B1: The historic urban area provides diverse recreational activities. | 0.881 | 0.742 |

| B2: The historic urban area provides various types of cultural exchanges. | 0.729 | ||

| B3: The historic urban area regularly hosts cultural activities, such as folk ceremonies, festive celebrations, and performances. | 0.767 | ||

| B4: The historic urban area blends harmoniously with the daily life of local residents. | 0.719 | ||

| Environmental atmosphere | C1: The signs at the historic urban area are esthetically appealing and blend seamlessly into the overall environment. | 0.870 | 0.720 |

| C2: The background music and lighting design of the historic urban area create a strong scenario-specific atmosphere. | 0.776 | ||

| C3: A strong historic and cultural atmosphere is created around the historic urban area through the use of color, decorations, and cultural symbols. | 0.668 | ||

| C4: The historic urban area is clean, hygienic, and comfortable in general. | 0.755 | ||

| Information and services | D1: The historic urban area provides convenient information guidance. | 0.865 | 0.724 |

| D2: The historic urban area provides various information media. | 0.736 | ||

| D3: The historic urban area provides comprehensive information and services for tourists. | 0.751 | ||

| D4: The service personnel of the historic urban area behave with proper etiquette. | 0.697 | ||

| Perceived value | E1: Visiting the historic urban area is highly beneficial (as I gain more experience and knowledge). | 0.828 | 0.748 |

| E2: Visiting the historic urban area is pleasant. | 0.742 | ||

| E3: Spending time and money touring the historic urban area is worthwhile. | 0.745 | ||

| Behavioral intentions | F1: I will share my experience of this trip with others. | 0.803 | 0.744 |

| F2: I would recommend the historic urban area to others after this trip. | 0.727 | ||

| F3: I will revisit the historic urban area if the opportunity arises. | 0.724 |

| Variable | Item | Standard Load Factor (Std. Estimate) | AVE | Combined Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical factors | A1: The historic urban area has abundant natural landscape resources. | 0.773 | 0.672 | 0.891 |

| A2: The historic urban area has multiple historical and cultural buildings. | 0.777 | |||

| A3: The historic urban area has a well-developed infrastructure. | 0.872 | |||

| A4: The historic urban area has abundant cultural relic resources. | 0.854 | |||

| Social activities | B1: The historic urban area provides diverse recreational activities. | 0.837 | 0.650 | 0.881 |

| B2: The historic urban area provides various types of cultural exchanges. | 0.818 | |||

| B3: The historic urban area regularly hosts cultural activities, such as folk ceremonies, festive celebrations, and performances. | 0.791 | |||

| B4: The historic urban area blends harmoniously with the daily life of local residents. | 0.777 | |||

| Environmental atmosphere | C1: The signs at the historic urban area are esthetically appealing and blend seamlessly into the overall environment. | 0.775 | 0.633 | 0.873 |

| C2: The background music and lighting design of the historic urban area create a strong scenario-specific atmosphere. | 0.857 | |||

| C3: A strong historic and cultural atmosphere is created around the historic urban area through the use of color, decorations, and cultural symbols. | 0.723 | |||

| C4: The historic urban area is clean, hygienic, and comfortable in general. | 0.822 | |||

| Information and services | D1: The historic urban area provides convenient information guidance. | 0.784 | 0.616 | 0.865 |

| D2: The historic urban area provides various information media. | 0.827 | |||

| D3: The historic urban area provides comprehensive information and services for tourists. | 0.775 | |||

| D4: The service personnel of the historic urban area behave with proper etiquette. | 0.753 | |||

| Perceived value | E1: Visiting the historic urban area is highly beneficial (as I gain more experience and knowledge). | 0.782 | 0.618 | 0.829 |

| E2: Visiting the historic urban area is pleasant. | 0.786 | |||

| E3: Spending time and money touring the historic urban area is worthwhile. | 0.791 | |||

| Behavioral intentions | F1: I will share my experience of this trip with others. | 0.767 | 0.575 | 0.803 |

| F2: I would recommend the historic urban area to others after this trip. | 0.753 | |||

| F3: I will revisit the historic urban area if the opportunity arises. | 0.756 |

| Physical Factors | Social Activities | Environmental Atmosphere | Information and Services | Perceived Value | Behavioral Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical factors | 0.820 | |||||

| Social activities | 0.284 | 0.806 | ||||

| Environmental atmosphere | 0.311 | 0.279 | 0.796 | |||

| Information and services | 0.280 | 0.384 | 0.415 | 0.785 | ||

| Perceived value | 0.450 | 0.385 | 0.476 | 0.473 | 0.786 | |

| Behavioral intentions | 0.382 | 0.445 | 0.421 | 0.445 | 0.497 | 0.759 |

| Measurement Relationship X→Y | Non-Standardized Path Coefficient | SE | z (CR Value) | p | Standardized Path Coefficient | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical factors | → | Perceived value | 0.242 *** | 0.053 | 4.560 | 0.000 | 0.291 | Support |

| Physical factors | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.130 * | 0.061 | 2.148 | 0.032 | 0.150 | Support |

| Social activities | → | Perceived value | 0.122 * | 0.053 | 2.291 | 0.022 | 0.149 | Support |

| Social activities | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.192 ** | 0.059 | 3.256 | 0.001 | 0.225 | Support |

| Environmental atmosphere | → | Perceived value | 0.254 *** | 0.065 | 3.906 | 0.000 | 0.272 | Support |

| Environmental atmosphere | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.144 * | 0.072 | 1.990 | 0.047 | 0.148 | Support |

| Information and services | → | Perceived value | 0.241 *** | 0.066 | 3.651 | 0.000 | 0.268 | Support |

| Information and services | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.192 ** | 0.074 | 2.597 | 0.009 | 0.205 | Support |

| Perceived value | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.241 * | 0.098 | 2.462 | 0.014 | 0.232 | Support |

| Item | c Total Effect | a | b | a × b Mediating Effect Value | a × b (Boot SE) | a × b (95% BootCI) | c’ Direct Effect | Conclusion | Effectiveness Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A→E→F | 0.166 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.047 | 0.020 | 0.018~0.095 | 0.120 * | partial mediation | 27.987% |

| B→E→F | 0.244 ** | 0.144 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.006~0.062 | 0.215 ** | partial mediation | 11.662% |

| C→E→F | 0.203 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.050 | 0.019 | 0.017~0.090 | 0.153 ** | partial mediation | 24.802% |

| D→E→F | 0.204 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.046 | 0.018 | 0.016~0.087 | 0.158 ** | partial mediation | 22.618% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, P. Unraveling Tourist Behavioral Intentions in Historic Urban Built Environment: The Mediating Role of Perceived Value via SOR Model in Macau’s Heritage Sites. Buildings 2025, 15, 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132316

Liu J, Zhu Y, Liu J, Wang P. Unraveling Tourist Behavioral Intentions in Historic Urban Built Environment: The Mediating Role of Perceived Value via SOR Model in Macau’s Heritage Sites. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132316

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiaxing, Yongchao Zhu, Jing Liu, and Pohsun Wang. 2025. "Unraveling Tourist Behavioral Intentions in Historic Urban Built Environment: The Mediating Role of Perceived Value via SOR Model in Macau’s Heritage Sites" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132316

APA StyleLiu, J., Zhu, Y., Liu, J., & Wang, P. (2025). Unraveling Tourist Behavioral Intentions in Historic Urban Built Environment: The Mediating Role of Perceived Value via SOR Model in Macau’s Heritage Sites. Buildings, 15(13), 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132316