1. Introduction

The territory of Peru is characterized by an enormous diversity of ecological systems, which is basically explained by the convergence of the Andes, the highest tropical mountain range, and the Humboldt cold water current, which runs along its Pacific Ocean coast, as well as the presence to the east of the tropical rainforests of the Amazon.

This diversity has produced significant variations in methods of inhabiting the region. Since the inception of civilization, in this expansive and varied region, the processes of plant and animal domestication evolved into the domestication of the environment, utilizing broad knowledge and technical resources that facilitated significant territorial adjustments. This resulted in the anthropic formation of a “second nature” inside the territories, exemplified in the Central Andes by the remarkable existence of numerous cultural landscapes, as varied and abundant as the diverse ecosystems found in the country.

However, despite the extraordinary diversity and transcendental value of the cultural landscapes preserved in Peru, we encounter profound difficulties in their recognition and, above all, in their conservation and heritage revaluation.

The Sondondo Valley is in the Ayacucho region, in the heart of the Andes. In 2019 it entered the World Heritage Indicative List, given the exceptional values of its ancestral cultural landscape. Our research facilitated the application by the Ministry of Culture before UNESCO.

We describe these values based on the characterization of various landscape units of pre-Columbian origin that make up the Sondondo territory. Among them are the Andean towns, with colonial roots, and the vernacular architecture that forms them, which are historically associated with the modeling of spectacular systems of cultivation terraces and platforms. These towns constitute the core of the rural dwelling and cultural identity of their inhabitants: in them, the architecture of the houses is uniquely integrated with varied open interior spaces, linked to the main landscape.

2. Background

Competitive project research funding provided by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) through its Annual Competition for Research Projects made possible the research project entitled Cultural Landscapes in the Sondondo Valley (Ayacucho, Peru), which has been carried out from 2015 through to now in several phases. The authors of this work have conducted research within the research project and have previously published their findings in conference proceedings and associated articles. The bibliography contains references to these works. This paper describes the project’s findings.

A diverse array of professional experts, including architects from a variety of specialties, including vernacular and project architecture, archaeologists, anthropologists, geographers, designers, and cartographic experts, as well as undergraduate and graduate students, have collaborated on this project. Additionally, the Cultural Landscape Directorate of the Ministry of Culture of Peru has provided institutional support. Thus, the initiative has integrated a variety of perspectives and knowledge regarding this region.

Simultaneously, the location has emerged as a focus of attention for various academic disciplines, as well as in the research and initiatives proposed within the Master’s in Architecture, Urbanism and Sustainable Territorial Development (AUTS) program at the PUCP. The program has organized a series of intensive workshops in the Valley every six months, during which students and teachers engage in a rigorous week of work in the town and with the community (

Figure 1). The local community receives the findings of these seminars, as well as the postgraduate theses that focus on the diverse themes suggested by the built heritage.

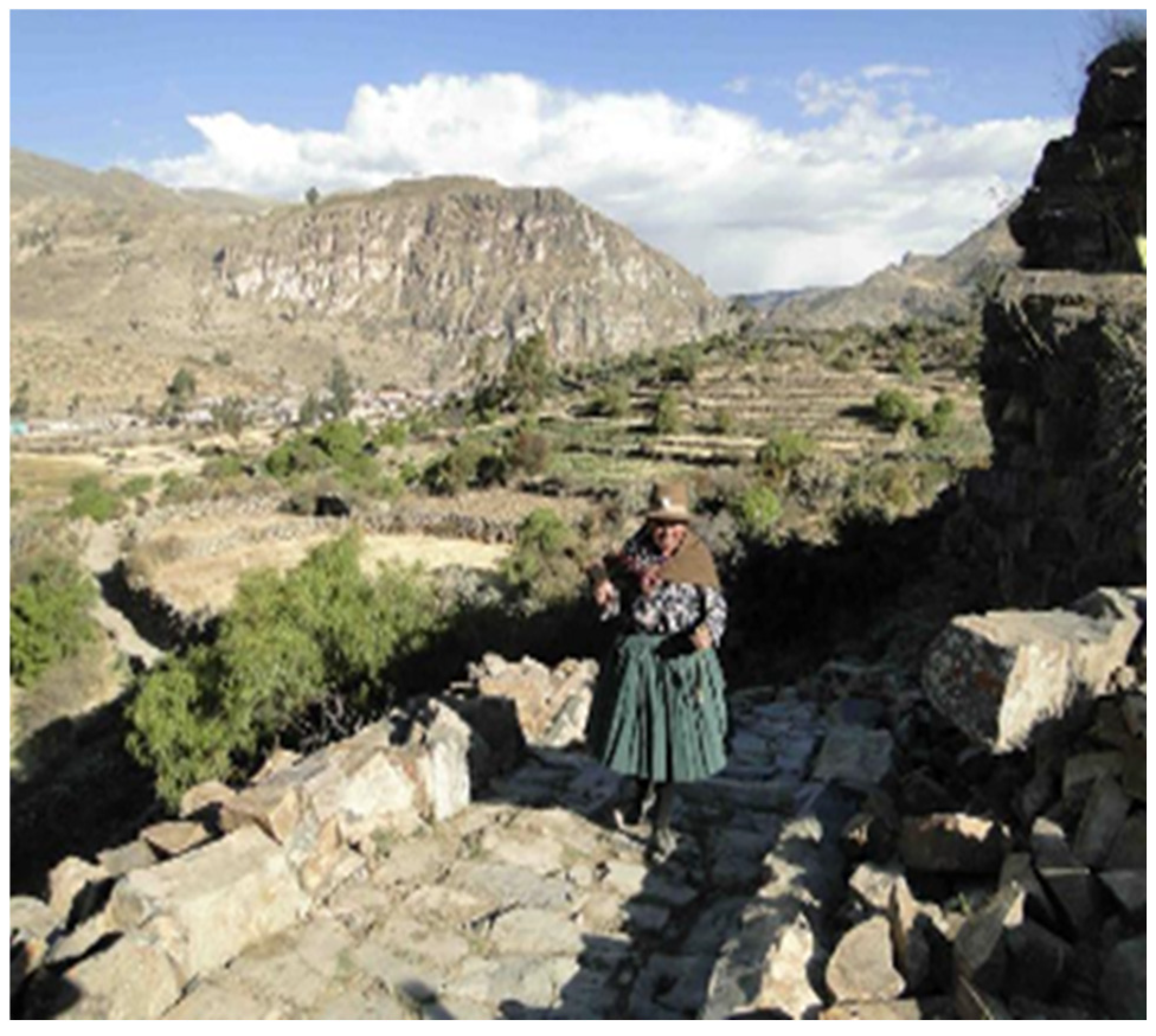

During the time we spent at the research site, we lived and worked together with the people of the Valley, who are a cohesive community, heirs to the collective values of the Andean peoples. We shared their daily routines, their productive and residential spaces of their daily lives, as well as the public, shared representative and symbolic space. We simultaneously carried out formal, institutional activities, together with municipal and community authorities. As part of that knowledge sharing and intercultural dialogue, we conducted visits to the territory accompanied and advised by local Quechua-speaking people, who treasure the memory of the places and the ancestral knowledge of the inhabitants of the Valley (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

This collaborative endeavor enables us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the site and to assist in the preservation and restoration of its values, despite the opposing current reality. We strive to cultivate a collective perspective on the Valley, its surviving heritage, and the landscape that serves as a vital foundation of the cultural identity of its people and which creates a heritage site, with a view of the potential emergence of a tourism industry that may drive development but also poses certain threats.

The documentation that substantiated the application of the Sondondo Valley as a World Heritage site was compiled on the basis of the concept of an inhabited, living, and fertile landscape. This perspective of territory administration and handling must be maintained. In December 2018, the Ministry of Culture organized an International Technical Assistance Workshop for the Indicative List of Peru, during which UNESCO experts were requested to collaborate on blurring the hard boundaries between the natural and the anthropic when defining a cultural landscape with a view to leveraging the notion of a landscape as a dynamic and evolving entity, sustained over time by the ancestral action of the peoples who are among its integral components [

1,

2].

3. Territory and Cultural Landscapes

Located between the Pacific Ocean and the Amazon rainforest, Peru’s territory is characterized by its significant ecological and environmental value [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The Andes Mountains range, which structures the territory with immense plateaus and a sequence of valleys embedded in the mountain range, emerges as a backbone between them. The rivers that pour their waters down the eastern and western slopes have created conditions for the emergence of life since ancient times.

The combination of this geographical–territorial condition at a tropical latitude should result in a distinct climate. Nevertheless, the Humboldt current, which ascends along the Pacific coast from the south and cools the coastal band contour, alters this condition and creates another intriguing paradoxical space, a vast arid desert, devoid of rain but humid and interrupted by the valleys that descend from the mountain range, that is home to most of the country’s population (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The variety of unique ecological systems, which are also a result of the diverse altitudinal and climatic conditions that occur in this tropical region, generate an unprecedented biological bounty, resulting from the geographic and environmental diversity (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The immense diversity found in Peru’s territory has resulted in 84 identified life zones out of the 108 known zones on Earth. Such ecosystem diversity has created conditions that are frequently too extreme for life, where nonetheless diverse cultures and civilizations have built over millennia environments suitable for living [

7,

8,

9].

During the inception of civilization in this vast and diverse region, the processes of domestication of plants and animals were expanded to include the domestication of the environment. This was achieved through the use of a variety of technical resources and knowledge, which resulted in transcendental territorial modifications. These modifications addressed the provision of water, the enhancement of soils, and adaptation to climatic conditions. This process consistently demonstrates the incorporation of interventions fitting the unique characteristics of the territories, in order to allow the breeding of plants and animals and to guarantee the sustainability of human settlements [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

In the Central Andes, the exceptional presence of numerous cultural landscapes, as numerous and diverse as the various ecosystems in the nation, is a manifestation of the extensive territorialization process that results in the anthropic configuration of a “second nature” [

18].

Along the coastal band, the rivers that flow down the western flank of the Andes permitted farming these desert territories though requiring construction of canal systems to ensure crops’ artificial irrigation (

Figure 8). Where water was scarce or flow limited, aquifers were cleverly exploited, either by digging holes in the ground so that the roots of the plants had, by capillarity, the necessary humidity to grow, or also by excavating underground galleries to conduct the water from the aquifer to the surface and thus create agricultural oases in areas of extreme aridity (

Figure 9) [

19,

20,

21].

The necessity of constructing vessels made of totora reeds for navigation and the significance of fishing as the economic mainstay of coastal civilizations necessitated the establishment of artificial lagoons for totora cultivation (

Figure 10). Similarly, salt marshes and drying systems were established to facilitate the conservation and distribution of fish using the dry salting technique (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) [

17,

22,

23].

A technique was employed to capture water in extremely arid regions, where there were no water courses or underground aquifers, but cloud forests grew on adjacent hills, where suspended water particles in the fog condensed. Infiltration channels further enhanced the retention of condensed water in the vegetation, thereby promoting the growth of tree and shrub cover. The water that was captured from the fog was subsequently directed to the lower elevations, where it was used to feed extensive cultivation terraces (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) [

17].

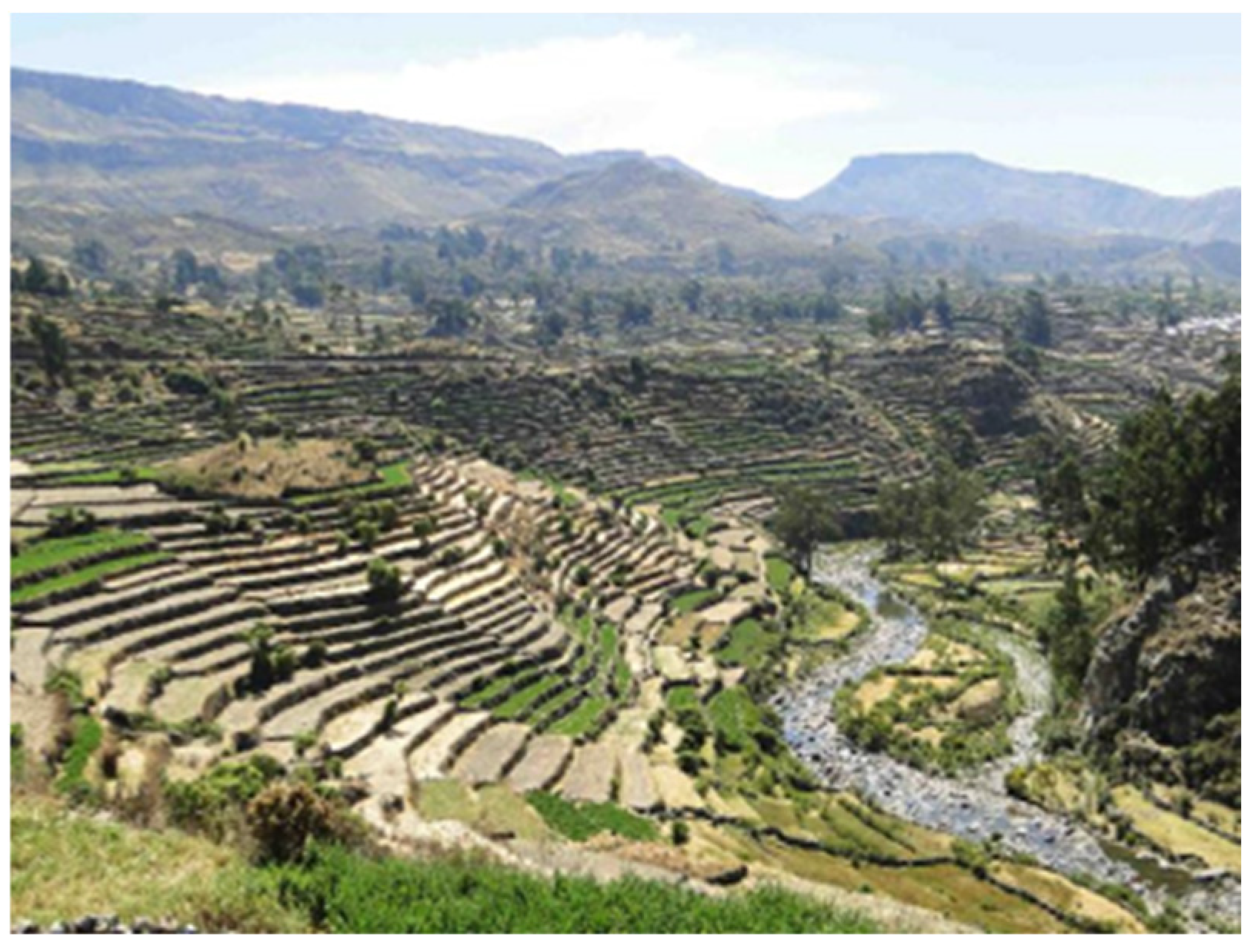

The extreme slope of the hillsides, the rugged topography of the inter-Andean valleys, and the marked temperature fluctuations in the high Andean zones would have rendered agriculture impossible in the absence of interventions to construct land that was suitable for cultivation. For this objective, two primary systems were implemented: agricultural terraces and cultivation terraces (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

Cultivation terraces, which are slow-forming and used for rainfed crops, are dependent on rainfall and are formed by establishing shrub and stone borders that adhere to the contour lines. They contain the soil that accumulates gradually as a result of farming and reduces soil erosion, enhances soil quality, and helps retain rainwater humidity. Conversely, agricultural terraces are not solely designed to produce soil; rather, they are primarily intended to facilitate its management through irrigation, thereby ensuring production and enabling multiple harvests. The terraces also provide collateral benefits by enabling water retention in the watersheds, thereby limiting erosion and calamities caused by natural events, as well as by protecting against the rigors of the climate and frost [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Natural pastures facilitate the extensive raising of camelid cattle in the high plateaus of the

puna, as will be detailed below. The most suitable locations for camelid raising are those with an abundance of water. Consequently,

bofedales, which are either expanded or man-made high-altitude wetlands, significantly alter landscapes. These wetlands are constructed through the branching of water from tiny torrents and springs or the construction of reservoirs (

Figure 17 and

Figure 18). Closely associated with camelids’ grazing in the

puna and in proximity to the wetlands, there are different types of corrals for the guarding of livestock where shepherds’ also build their shelters [

17,

28].

Finally, it should be noted that these main landscape units, which we have briefly reviewed, are often articulated or intertwined with each other, generating systemic integrations on a larger scale.

4. The Cultural Landscape of the Sondondo Valley

The Sondondo Valley is situated in the central-southern highlands of Peru, in the high Andean region of Ayacucho in the province of Lucanas. From the city of Nazca (520 masl), which is situated 450 km south of Lima, the Valley is accessible by ascending swiftly eastward to the heights of the

puna plains (4000–5000 masl). From there, a detour of approximately 80 km to the north is necessary to reach Puquio (3200 masl), which is 140 km away, and from there, taking a detour of about 80 km to the north, you reach the Valley [

29,

30].

The

Qhapaq Ñan, the Royal Road of the Incas, which cuts across this region, is evidence of its historical connection to the coast. Currently, modern highways provide a transversal connection between the two [

30,

31].

From the

puna plains that dominate the region, one can see the marked and steep ravines that make up the high basins and headwaters of the Negromayo and Mayobamba rivers, which converge to form the Sondondo River, after which the valley is named. This territory shows the traces of its intense volcanic origins, as well as the erosive processes produced by the dynamics of glacial phenomena that took place millions of years ago, followed by erosion and sedimentation of alluvial deposits. The territory’s remote volcanic origin is evidenced by its own tutelary mountains, the apus in Quechua, as well as the multiple hot springs, the stone forests, and the cliffs that surround the Sondondo River and characterize its unique landscape (

Figure 19) [

17,

30,

31,

32,

33].

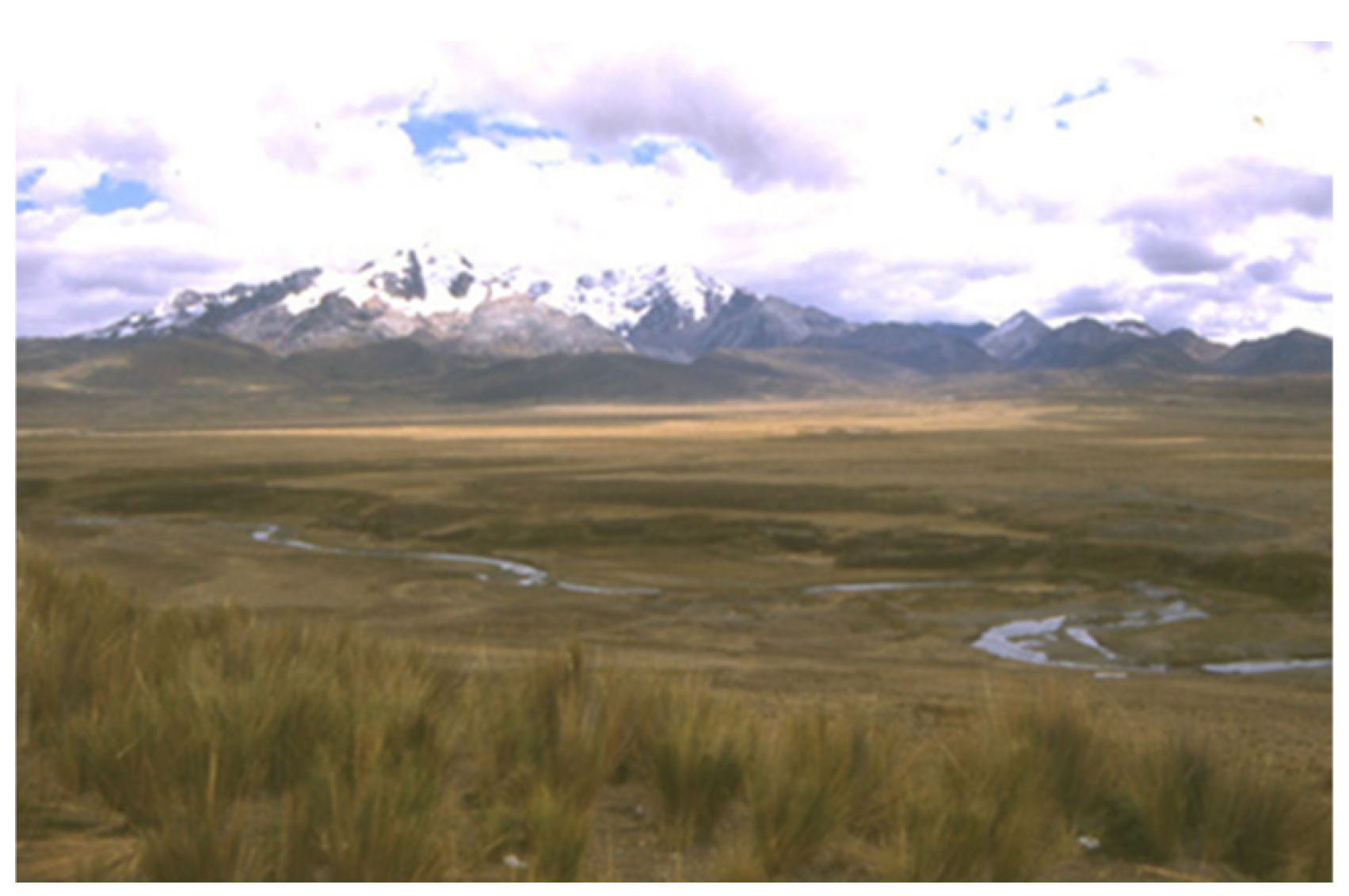

The altitude of the dominant high plateau, which is characteristic of the

puna ecology, has influenced the geography of this landscape. The predominance of South American camelid livestock rearing in this region is due to the breed’s resistance to extremely cold climates. Community members who intermittently inhabit the heights graze the herds in the vast grasslands and high-altitude wetlands that have supported the populations of wild vicuñas, and domesticated llamas, and alpacas since time immemorial. Since colonial times, sheep and cattle have also been present (

Figure 20).

Valleys flanked by the puna plains cross the quechua ecological floor (2500 to 3500 masl), where a more temperate climate permits farming on historical dry and irrigated terraces that are still in use today.

The primary populated areas, which are villages derived from colonial reductions, are also located at the same altitudinal level and are associated with the main terracing systems. Indigenous archaeological settlements occasionally occur in close proximity and continue to engage in dialogue with the territory under the colonial layout, demonstrating a significant continuity in the historical settlement of the Valley by its inhabitants across various periods [

34].

The ancestral management of the transversal and altitudinal articulation between the

puna and

quechua zones and the integration between agriculture and livestock raising are the productive territorial strategies that make life in the Andes possible. Moreover, these places condense the character of the territorial memory and express the landscape’s cultural identity. Intrinsically linked to their productive potential, the Andean societies’ cosmovision evolves within an animated and consistently sacralized terrain. This region of the Valley, dominated by the peaks of two prominent volcanic mountains, Qarwarazu (5124 m above sea level) and Osjonta (4597 m above sea level), which serve as symbolic

apus or guardian deities, features wetlands and corrals that are characteristic landscape units of the high Andean zones (

Figure 21 and

Figure 22) [

12,

13,

17,

35,

36].

The

bofedales are relatively simple ancestral territorial interventions that divert or dam small watercourses to expand the wetlands and improve the quality of the pastures. Different types of corrals are associated with these grazing sites, whose enclosures extend in the form of petals, to support the shepherds’ management of different livestock breeds. Attached to these corrals, skillfully built with dry stone walls, are small structures made with the same technique and thatched with

ichu straw (

Stipa ichu), that provide austere shelter to the shepherds (

Figure 23 and

Figure 24).

The administration of wetlands and bofedales in the high plateaus of the puna facilitates water retention and infiltration, initiating a beneficial cycle that generates reservoirs or oxbow lakes downstream, along with springs that discharge water to channel it down the valley through canals for irrigating agricultural terraces and supplying water to villages.

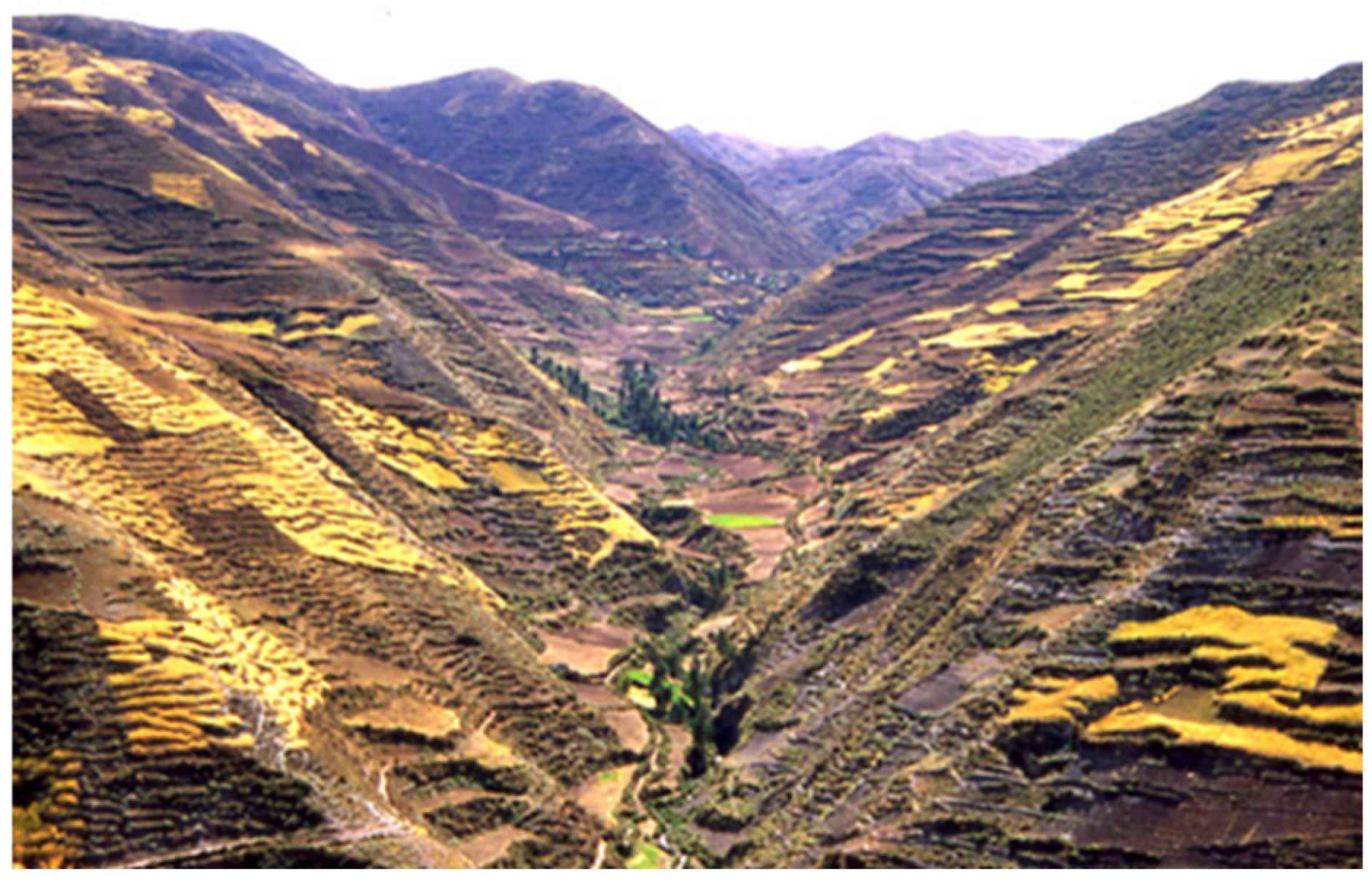

Down the mountain slopes from the

puna, we reach the suni ecological levels (3500 to 4000 masl), exhibiting extensive terraces of rain-fed crops reliant on precipitation (

Figure 25). At lower elevations lie the

quechua zones (2500 to 3500 masl), characterized by significant expanses of terraces and cultivated areas equipped with irrigation systems (

Figure 26) [

17].

The biggest concentration of human settlements, closely associated with these agricultural landscape units, is currently documented at the archeological level, spanning a temporal sequence from the Formative period (1500–500 B.C.E.) to the Inca Empire (1450–1532 C.E.). This sequence demonstrates an ongoing and cumulative process of territorialization, and reminds us that we face a changing terrain, particularly regarding the evolution of the

andenería systems [

26,

37,

38].

Its more temperate climate and its proximity to areas of higher agricultural productivity has resulted in the continued human occupation of this territory (

Figure 27), despite the destructuring brought about by the Spanish conquest and the consequences of colonial domination for the indigenous world.

5. The Andean Towns

The colonization of the Americas, and in this case, the Andean territory, entailed an intense and radical process of transformation, not only of the political, economic, and social structure, but also of the territory. This transformation had the population centers as its center of irradiation, understanding the territory from an extractivist perspective and as a productive resource, diametrically opposed to the indigenous (productive) integration with the nature of the territory and the sacralization of the components of the landscape.

The intricate and robust sensory connection of the Andean populace with their surroundings is manifested in the creation of these cultural landscapes and settlements, which reflect a unique worldview and communal relationship with other entities, significantly disrupted by the emergence of a fundamentally different culture.

The “colonial city” in this region, characterized by its viceregal nature, is inherently founded on concepts of order, linked to geometry, and emphasizes form as a crucial element in its realization. Despite the immense diversity of indigenous Andean settlements, which exhibit greater organicity and versatility than their colonial counterparts, the potency of form and geometry was also evident in various pre-Hispanic settlement and architectural styles, particularly during the Inca period. This era rapidly assimilated the practices of preceding cultures, culminating in a remarkable manifestation of landscape architecture characterized by profound visual and compositional strength.

The colonial reductions, or Indian villages, as termed in Viceroy Toledo’s ordinances, involved the mobilization of the local populace, severing their connections to the landscape that sustained their identity. These were mechanisms for the control and evangelization of indigenous populations, structured according to a grid system. Contrary to prevalent notions, settlement in the Valley during the latter part of the 16th century occurred not distantly from this geographical framework, but rather typically in close proximity to the ancient indigenous settlements and the most fertile agricultural terraces (

Figure 28).

The relocation of the existing communities and the consolidation of the indigenous population into new towns occurred through the implementation of a grid layout on relatively level terrain, which was both practical and seemingly suitable for agricultural usage at that time. The colonial establishment, characterized by the typical grid layout, was likely imposed onto the pre-existing rural structure and its associated agricultural infrastructure, including terraces, canals, and pathways (

Figure 29 and

Figure 30). The manifestation of this intricate installation process was reflected in the morphology of the Valley’s colonial settlements, where elements of resistance, negotiation, and adaptation were necessary between the imposition of colonial authority and the dynamics of indigenous communities, as observed in various other instances elsewhere [

39,

40,

41].

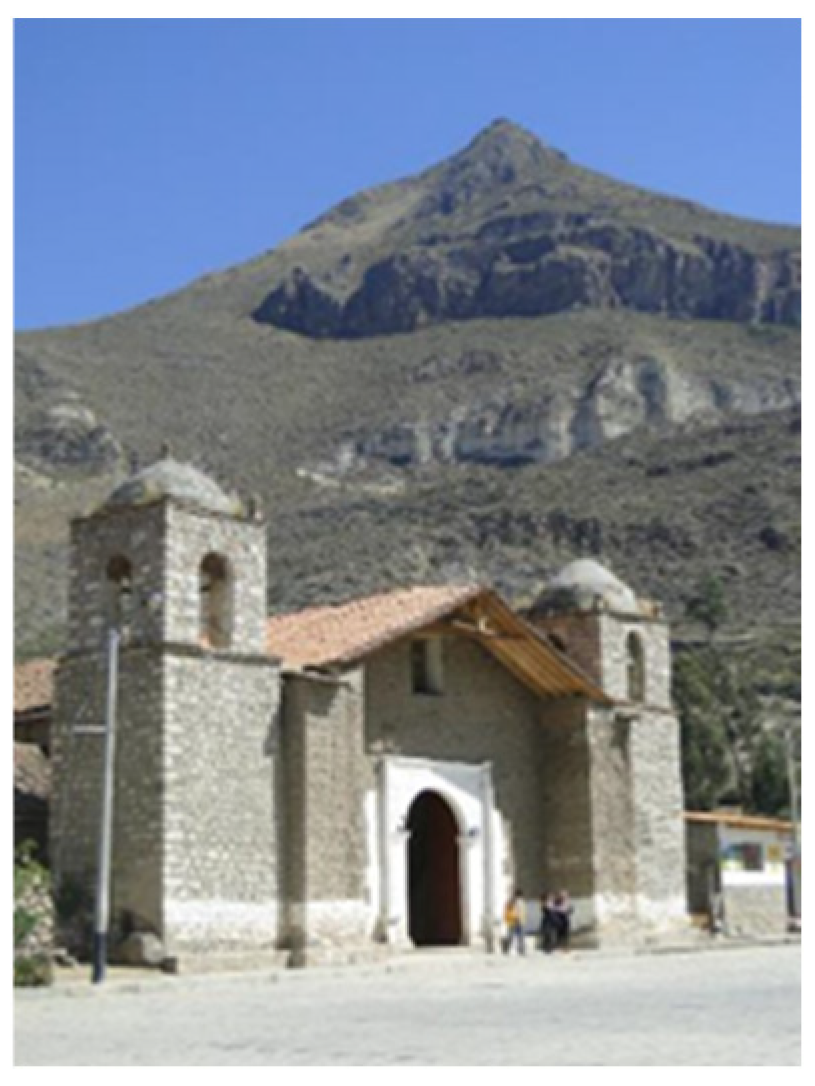

The arrangement of the principal colonial towns in the valley, including Andamarca, Aucará, Cabana, Ccecca, Chipao, Huaycahuacho, Ishua, Mayobamba, and Sondondo, features a central plaza that is a reminder of this colonial design, housing the church and key public edifices. While these main squares exemplify colonial public spaces symbolizing emerging authorities, they are not invariably centrally positioned within the pattern; instead, they are often situated to one side or at one extremity of the arrangement.

Most churches in these squares are not canonically oriented towards the east, but rather seem to have been oriented so that their facades would have the apus or tutelary mountains as a background landscape, which can be interpreted as a form of syncretism, or negotiation, between the imposition of Christian rituals and the permanence of the reverence for the sacralized mountains of the Andean cosmovision (

Figure 31,

Figure 32 and

Figure 33).

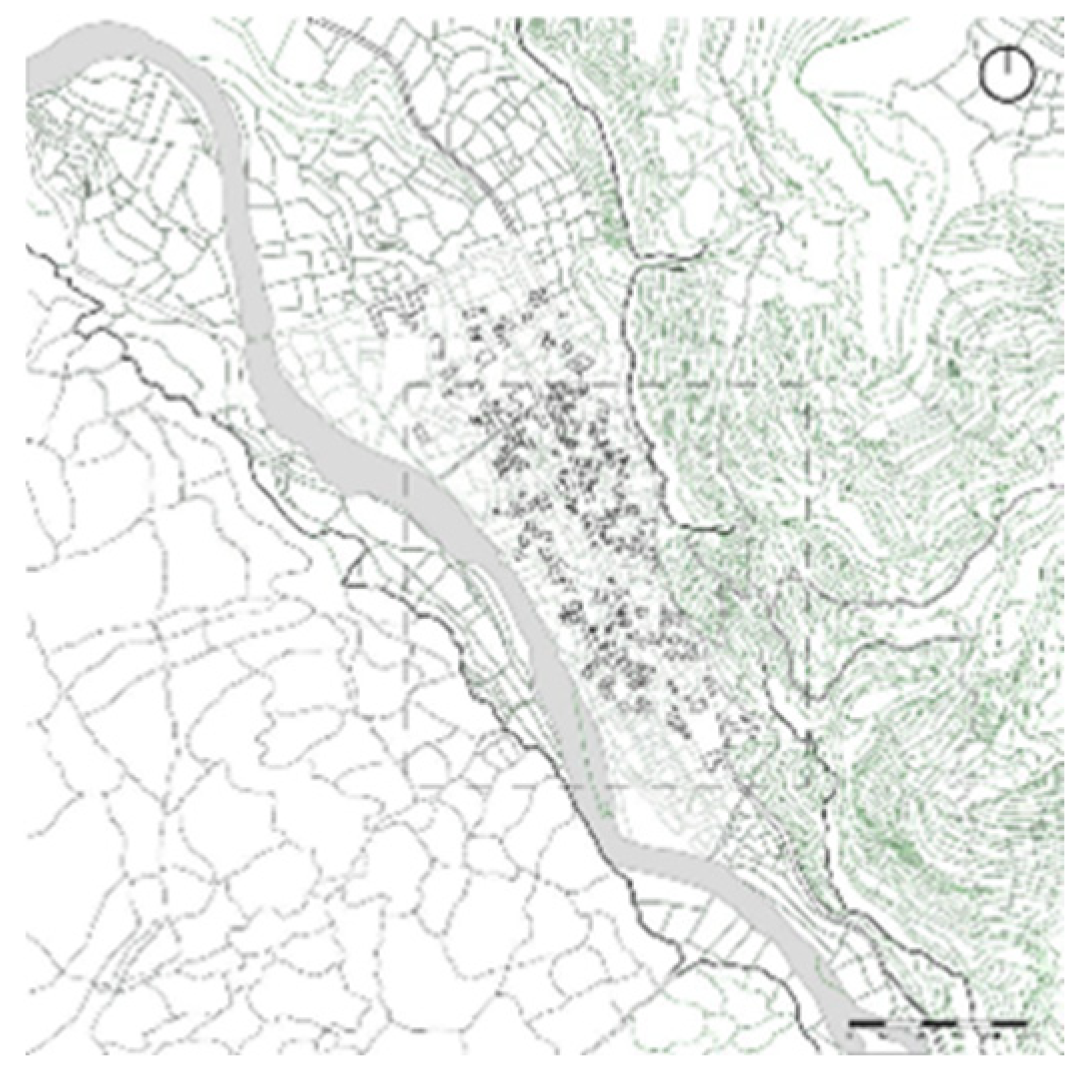

Drone and captured satellite orthophotos for our project reveal that, in addition to the alignment of buildings with street fronts, open spaces dominate within the blocks, featuring an organic arrangement of gardens, orchards, farms, corrals, and other structures that do not adhere to the orientation of the street axes. An anthropological analysis of the underlying causes for this pattern elucidates the rural lifestyle of its residents. Gardens and orchards are utilized for cultivating vegetables, aromatic, medicinal, or ornamental plants, fruit trees, and as seedbeds. Additional areas serve as enclosures for the protection and milking of livestock kept near houses, as well as for the treatment of ill animals, those nearing parturition, or their young [

42,

43,

44].

This unique arrangement of the villages’ blocks reflects the distinctly rural nature of these communities and the lifestyle of their residents (

Figure 34,

Figure 35 and

Figure 36), despite public authorities categorizing them as “urban” based on a flawed statistical and quantitative interpretation of mere population aggregation. This distortion results in the presumption that the planning and management tools align with the urban, if not metropolitan, standards set out by the State in its relevant rules [

45,

46]. Consequently, urban concepts are imposed on these towns, desensitizing them and resulting in the adoption of foreign forms. Instead, their unique plot design illustrates the rural origins and cultural identity of their inhabitants, reflecting the connections between residential areas and the agricultural and pastoral lands located both nearby and at a greater distance.

The colonial urban layout reflects a concept of order derived from geometry, seen in the alignment of streets and the configuration of architectural volumes that display façade fronts, as well as a notion of civic space associated with the power structures present in the square. In equilibrium with them, towards the interior, there exist open areas associated with agricultural activities, featuring strong visual connections to the (sacralized) mountains of the surrounding landscape, facilitating a diversity of uses and living experiences (

Figure 37). This plan, despite its rigidity, accommodates pre-existing developments and demonstrates many forms of adaptability examined in our research project. They encompass intermediary spaces, galleries, vestibules, and gateways, characterized by a synthesis between the public and private, the open and closed, along with an architecture possessing a distinct personality. This palimpsest weave demonstrates continuity with the territorial palimpsest of the Andean region and with other cultural expressions [

34,

43,

47,

48,

49].

In conducting our research in the Sondondo Valley, we validated the essential role of the historically documented settlement forms in the territorial construction of the Valley and its cultural landscape. Such is the case of the Wari administrative center of Jincamoco (600–1000 C.E.) or the archaeological settlement of Caniche (1000–1532 C.E.), both of which are outstanding examples that confirm the intense links between settlement and development styles, especially in landscape units showing intensive agricultural and livestock productive activities, that is, the areas modeled with terrace systems and platforms [

37,

38].

This approach enables the reconstruction of the significance of population centers in pre-Hispanic times regarding the characterization of the built landscape, serving as hubs for territorial development and as sites that encapsulated the essence of habitation while integrating the cultural identity of the territory. Following the traumatic consequences of the Spanish conquest and the installation of colonial rule in the 16th century, a reterritorialization process occurred, linked to the formation of reductions or Indian villages. A complex transculturation process is uniquely reflected in the layout of these new settlements and the vernacular architecture that defines them, exceptionally expressing the cultural syncretism that continues to characterize the cultural identity of the Valley’s inhabitants.

6. Vernacular Architecture

Since the onset of the colonial era, architecture, encompassing both public and residential structures, evolved in these regions in accordance with the principles derived from Spain and the Mediterranean, while adapting to various local conditions, including geography, climate, and available construction resources and techniques. Similarly, the involvement of indigenous peoples in construction activities and the preservation of specific local traditions, particularly in rural regions distant from urban centers, initiated a process of hybridization and crossbreeding that culminated in what is broadly referred to as traditional Andean architecture [

43,

47,

48,

49,

50].

The traditional architecture of the Sondondo Valley is part of the Ayacucho regional traditions and shares common features with Andean vernacular architecture, from the privileged use of earth and stone as construction materials, to the configuration of its volumes and finishes.

This austere Andean architecture is composed from the typological and compositional point of view by volumes of earthen architecture that, in the case of the houses, are made up of one or two levels and one or two bays aligned with the street. It is a sober and volumetric architecture, as popular architecture usually is [

51,

52], with large walls and small openings, which towards the street usually have small box balconies on the second level and doorways with symbolic elements, with an intense sensory charge (

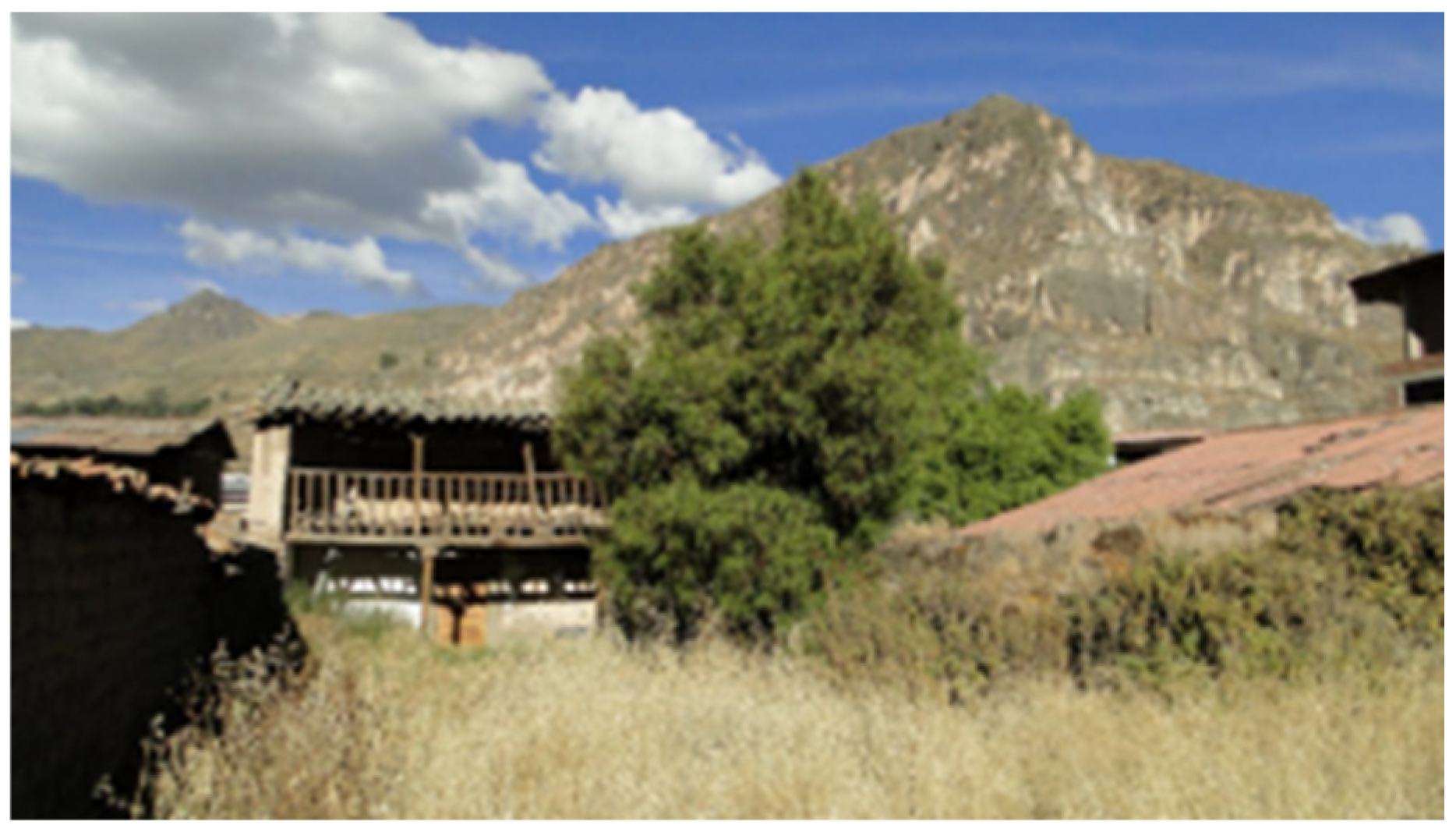

Figure 38). The volumes are crowned by an asymmetrical gable roof, since towards the interior it is designed to house and cover a gallery or corridor that opens towards the interior space of the block, open in turn to the sky. This gallery or corridor is an important intermediary space between the rooms and the courtyard or interior garden, where family life and some domestic activities take place, as well as a privileged place to receive visitors or hold reunions (

Figure 39).

Consequently, the expansive side doors, adorned with intricately carved stone pillars and arches, do not provide access to the rooms, as one might expect, but rather to the interior open areas and the corridor featuring rustic wooden benches or seats, which offer both seating and a pleasing view of the garden or orchard of the residence. These personal realms of familial existence and relationships, sustained by domestic endeavors, and the nurturing and cultivation of flora and fauna, are exposed to the expanse of the sky and the silhouette of the mountains, inside a landscape delineated by the arrangement of the constructed environment. Besides the enjoyment these areas provide to its residents, the constant observation of the sky and the changing cloud cover enables them to anticipate meteorological variations, so allowing them to tend to their crops or cattle as necessary. The architecture is once more connected to the internal landscape, resembling “landscape houses” where, surpassing the urban-colonial structure of the street, the privacy of the domestic realm is fully extended to the broader region.

Once the nighttime cold is overcome, the interior spaces of the blocks, open and at the same time sheltered, are lit from dawn by intense solar radiation, typical of the tropical latitude, turning them into pleasant places of sensory wellbeing. This climatic comfort is transmitted to the rooms that surround and configure the open spaces, which, in turn, provide natural lighting and ventilation, and incorporate the vision of the apus and the relationship with the landscape to the more intimate rooms.

From the construction point of view, this traditional architecture is made of stone walls and mud mortar or, mostly, adobe on stone foundations (

Figure 40). The walls are plastered with layers of mud and traditionally finished with a thin layer of white or red earth. In Quechua, white paint is called

qeqato. In the other colors,

ichma, which means paint, is juxtaposed with the designation of the color:

puka (red)

puka ichma, or

qillu (yellow),

qumir (green), in which mucilage extracted from cactus stalks is mixed [

53].

The structure of the roofs is preferably assembled with beams or logs of alder (

Alnus jorullansis), walnut (

Juglans neotropica), eucalyptus (

Eucalyptus) and even with the trunks of the inflorescence of the agave or maguey (

Agave). Onto this carpentry work is superimposed and secured a reed roof, on which is placed a mud and straw cake that, in turn, is the support and seat for the rustic clay tile roofing. The galleries of the corridors in their first level are supported either by slender wooden pillars, supported by carved stone bases, or by adobe columns, while the second level continues supported by wooden pillars, which also serve to support the wooden slatted railings (

Figure 41).

The materials and construction methods inherent in local architecture reflect a unique amalgamation of knowledge that influences both the selection and preparation of diverse material resources found in various ecological environments, as well as the management and preservation practices that ensure their availability in the territory, thereby shaping the landscape.

In this popular architecture, although self-construction resorts to ancestral knowledge and forms of work that call for cooperation and traditional reciprocity, such as the ayni, there are also trades that require certain levels of specialization and accumulated knowledge, as is the case of adoberos or adobe makers, stonemasons, and carpenters—a set of trades that the imposition of new forms of construction has been displacing, thus exacerbating the processes of economic impoverishment underway at the local level.

7. Heritage for Humanity

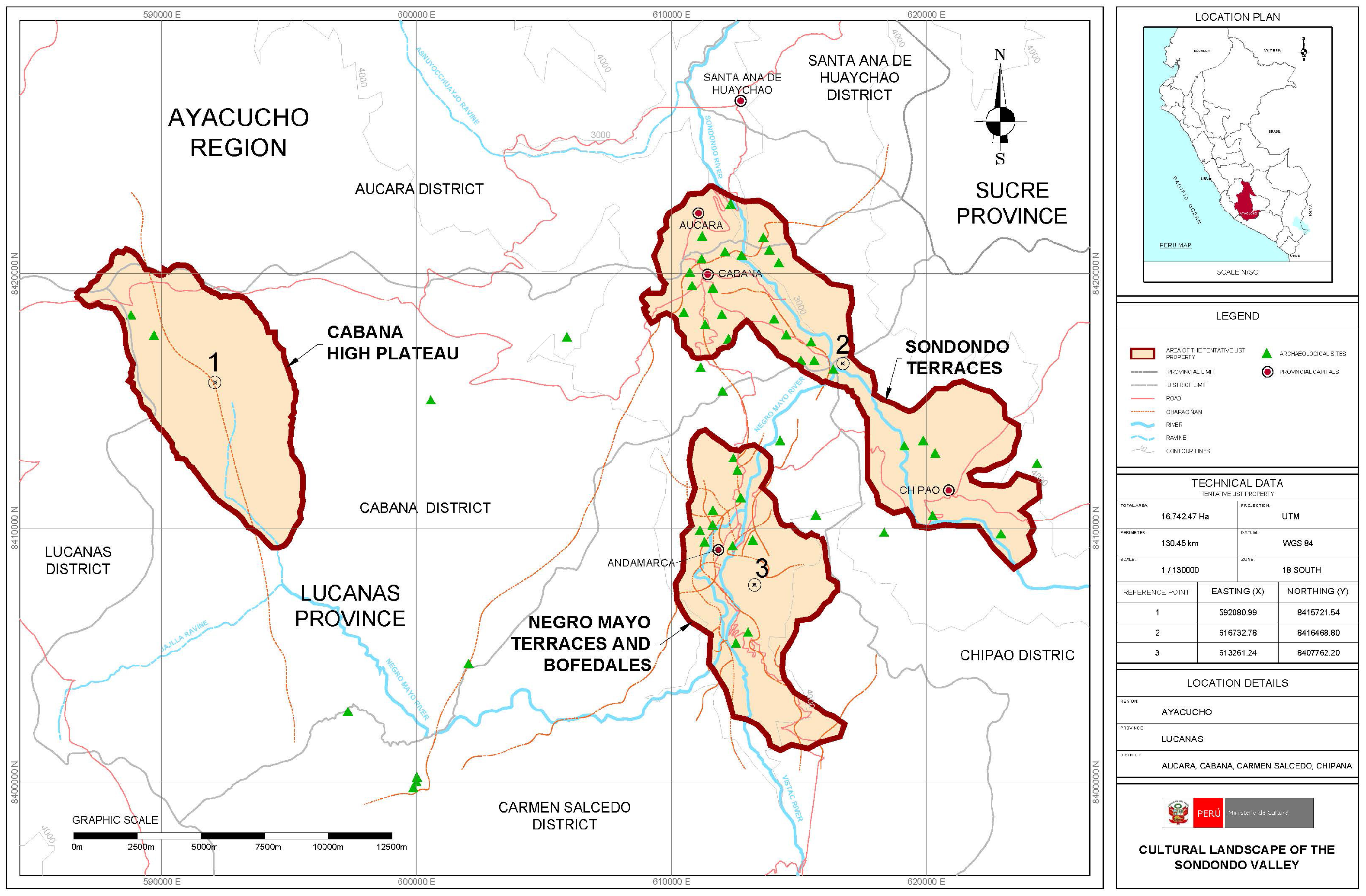

In 2019, the Sondondo Valley (

Figure 42) was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List, following a nomination by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture, partly based on our collaborative research work. This process was interesting as it helped us deepen our knowledge of the Valley in different respects.

The registration was made under the Cultural Heritage category, focused on the theme of Cultural Landscape, which, according to the Convention, refers to a diversity of manifestations of the special interaction between humanity and the natural environment [

54].

According to the definition, cultural landscapes often reflect sustainable forms of land use, based on the qualities of their natural surroundings, and may also show a spiritual relationship with nature. Therefore, the protection of cultural landscapes can contribute to sustainability and biological diversity.

It is important to highlight the importance for Peru of the nomination, and possible declaration, of cultural landscapes. Currently, and despite the vastness of Peruvian heritage, only thirteen assets (cultural, natural, and mixed) have been declared World Heritage; these declarations have been carried out between 1983 and 2021 [

55]. Nine of these properties have been designated as Cultural Property, and none as cultural landscapes, but rather as archaeological sites.

Pursuant to the definition of cultural landscape proposed by UNESCO, clearly due to the relationship of Andean communities with the territory, a large part of their territorial constructions could be called cultural landscapes. This is relevant to not only the Andes Mountains range and the coastal desert, but also to Amazonian communities, which also show an exceptional relationship with nature and a sophisticated heritage derived from it. The concept of cultural landscape, therefore, is a fundamental conceptual tool to protect the Peruvian territorial heritage, understood not only as an archaeological object, monument, and urban environment or built complex, but also considering its integrality and transversality.

Based on this understanding, in 1992, UNESCO adopted the concept of cultural landscape as a cultural asset. In Peru, which adhered to the Convention in 1981, the Ministry of Culture set up the Directorate of Cultural Landscape in 2011, provided with the legal framework for the registration, declaration, research, protection, enhancement, and management of the great diversity of cultural landscapes existing in Peru [

56].

Currently, 24 properties are on the Tentative List, most of which were submitted in the prolific year of 2019. Several of them could, due to their characteristics, be categorized as cultural landscapes. On the other hand, the Cotahuasi Canyon, presented as a natural asset, includes an exceptional display of agricultural terraces [

57].

In the Andean context, other emblematic valleys present conditions similar to those of the Sondondo Valley, such as the outstanding cases of Colca Canyon, Laraos, and Yauyos in the Cañete Valley, among others. However, the Sondondo Valley is a unique case with respect to declaring it a piece of world heritage.

In addition, the Peruvian regulation includes the term “living landscape” to refer to the second UNESCO subcategory of cultural landscape, i.e., “organically evolved landscape” [

54], and defines it as a “a continuing landscape […] which retains an active social role in contemporary society closely associated with the traditional way of life, and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress. At the same time, it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time” [

56].

This notion of a living landscape is fundamental in the Andean world and, especially, in the Sondondo Valley. Pursuant to UNESCO’s basic criteria, the unique values of the place are manifested both in its various landscape components and in the links that local communities weave with them. As stated in the report: “this cultural landscape is a reflection of the identity of the communities that inhabit it and that have inherited, preserved and transformed it in an ancestral way” [

30]. Conceptualization as a living landscape is essential to ensure its conservation, and to avoid its conversion into a museum object or fossilization as a protection mechanism.

This landscape results from the ancestral continuity in management and knowledge of agricultural technologies and forms of organization of communal work. The idea of the inhabited landscape, as the basis of its heritage value, requires, in addition to a theoretical construction, project tools that allow its conservation while maintaining its vitality.

In this regard, the application report highlights that “The Sondondo Valley—in addition to being a territory where intensive human occupation has materialized through the transformation of the environment—has become a scenario where the collective imagination of past and present populations has created sacred spaces and elements that are very important in the worldview, which remain alive and in use in daily practices. A good example of this is the recognition of the “

Danza de Tijeras” or Scissors Dance as Intangible World Heritage” [

30].

Further in the process of declaring a World Heritage site, criteria (iii), (iv), and (vi) were retained for the World Heritage nomination for the following reasons:

As required by Criterion (iii), namely, “to provide unique or at least exceptional testimony of a cultural tradition or a civilization that is alive or has disappeared” [

2], the Sondondo Valley exhibits technological processes and cultural traditions typical of Andean civilization. The conservation and continuity of use of pastoral structures, such as the typologies of livestock-keeping corrals, cultivation terraces, and irrigation systems, provide remarkable evidence, not only because of the significant transformations of the territory, but also because of the permanence of uses, technologies, symbolic meanings and agrarian festivities. Outstanding manifestations in this regard include representations of the landscape carved in rocks, replicating the modeling of the territory, with water reservoirs, canals, and cultivation terraces [

30].

Regarding Criterion (iv), i.e., “to be an eminently representative example of a type of construction or architectural or technological ensemble, or of a landscape that illustrates one or several significant periods of human history”, the Sondondo Valley has been the scene of a long evolution of territorial transformations that date back at least to the Formative period (1500–500 B.C.E.), and that, passing through different periods of the Andean world, reached their apogee during the Inca Empire (1400–1532 C.E.). The process continued under new terms after the conquest and the installation of Spanish colonial rule and is ongoing up to the present day. The agricultural and livestock landscape built in the Valley during this millenary process constitutes an invaluable testimony of the history of the Andean world [

30].

Regarding Criterion (vi): “be directly or materially associated with events or living traditions, ideas, beliefs, or artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance”, the symbolic character of the cultural landscape of the Sondondo Valley is manifested in its association with the cosmovision and symbolic practices of its inhabitants. The reverence to the apus or tutelary mountains is testimony to this, as well as the rituals and festivities associated with the agricultural calendar and infrastructure maintenance activities, especially irrigation. The Scissors Dance, declared national heritage, and whose apparent origin would be in the Valley, incorporates elements of the landscape, such as waterfalls, in the initiation rituals [

30].

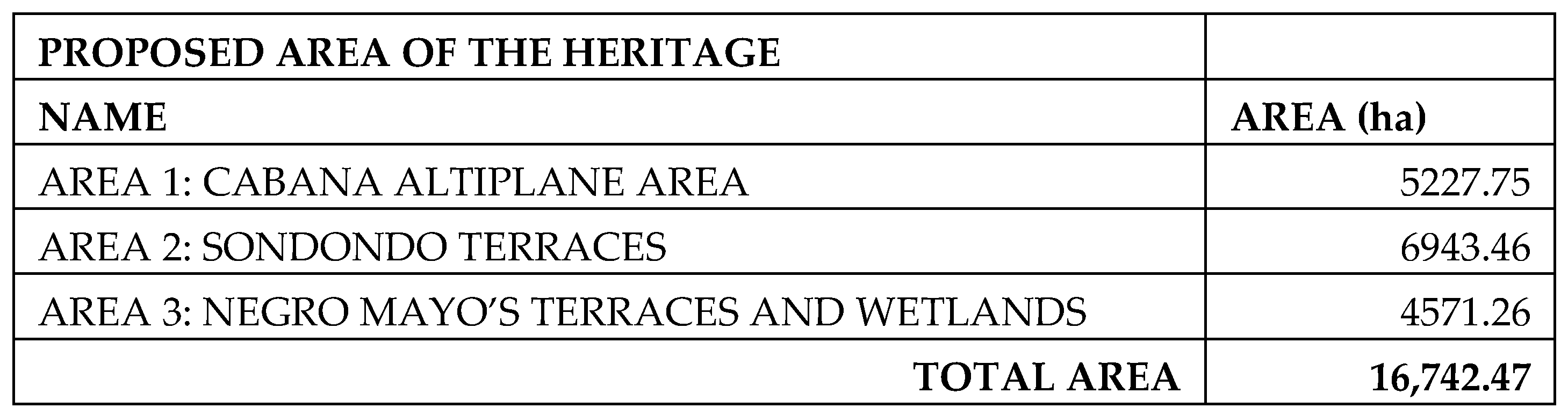

In addition, the Declaration of Authenticity and Integrity highlights the special transversal and altitudinal articulation of the Valley’s territory, between agricultural activities on the cultivation terraces and the grazing areas with the corrals of the livestock ranches. A first area is then proposed for registration as World Heritage, which includes most of the 16,742.47 hectares of terraces in the Valley, as well as the

puna territories and the irrigation system associated with them (

Figure 43). Also included are all the architectural and archaeological assets identified by the Ministry of Culture of Peru, and no less important, the management and governance exercised over the territory and its landscape by indigenous communities [

30].

The tangible and intangible characteristic of the Andean world, which nevertheless achieves a concrete materialization in the cultural landscape, leads to reflections on the idea of authenticity of the place, considering that the essential thing in this is the continuity of its cultural traditions. Likewise, the declaration of its universal and exceptional values was based on the duality between its representativeness and at the same time its uniqueness, since it was recognized that this valley, unlike other similar places, is “…the best-preserved example of an Andean agro-pastoral landscape in Peru.”

We find the necessary comparison with other places on a planetary scale, which UNESCO requires with other world sites for the nomination as World Heritage, and which permits understanding the global importance of this place. In most of them, the natural and human variables combine, while agricultural exploitation is part of the unity of an exceptional cultural landscape [

58]. One such case is the cultural landscape of Portovenere and Cinque Terre in Italy, exhibiting the masterful configuration of small towns in a rugged territory and communal cultivation terraces, of great beauty and cultural value, condensing the history of human settlements of the last millennium in the region [

59]. Other cases with similar characteristics categorized as cultural landscape, include the landscape of agaves and old industrial facilities of Tequila (Mexico), the cultural landscape of the Sierra de Tramuntana (Spain), the terraced vineyards of Lavaux (Switzerland), the Mediterranean agro-pastoral cultural landscape of Causses and Cévennes (France), the ancient agricultural site of Kuk (Papua New Guinea), and the cultural landscape of the terraced rice fields of the Hani of Honghe (China) [

58].

Finally, in the national context, we took into consideration the historic sanctuary of Machu Picchu, which was declared a mixed cultural asset in 2016, although it could also be considered a cultural landscape. This site combines an exceptional natural environment, on the eastern slope of the Andes, in the upper Amazon basin, and comprises an integrated terraced settlement system, although spanning a shorter time range than those of Sondondo [

60].

Ultimately, and beyond its declaration as a World Heritage site, it occurred to us that this place, in its essential values, in the global context, could be a space for reconciliation between people from different places, between people and the landscape, between present and past. We understand this past as part of our history, that is alive and active in the present. It is an opportunity for peace and reconciliation between many forces that today are beginning to strain and break. We wonder whether the declaration as a World Heritage site can contribute to recovering the fragile links in this Valley, which have always been a strength, in the face of external threats, and through this, the forces of change can find an appropriate channel.

8. Contemporaneity, Threats, Challenges, and Community

The evolution of social, economic, and environmental dynamics in contemporary history is, in part, a threat to the Sondondo Valley.

At the territorial level, ecosystems, which are relatively stable and solid under their historical conditions and traditional human activity, are at risk from phenomena such as water, air or soil pollution, or massive land exploitation, which unbalance the system and lead to the loss of livestock, biological or agricultural resources, especially in the context of climate change. Communal management and the resources of the people do not always manage to solve problems at this scale.

In this sense, the presence of the State is essential to provide major infrastructures, such as roads or large facilities, that can provide essential health, education, and production coverage. The challenge is to ensure that these services are provided in a way that is sensitive to lifestyles, carrying out projects that respect the current architecture and territory, and its forms of organization and social values. It is common to find that transport infrastructures destroy fundamental values of the territory, such as wetlands, and public facilities use typologies that are not adapted to the climate and landscape and that are insensitive to the knowledge accumulated in vernacular architecture.

The current dynamics of change in densely populated towns, characterized by ex-tensive services and commercial activity, are reshaping these areas, particularly along main streets. This transformation involves the gradual creation of open spaces, accompanied by the demolition of traditional structures and their replacement with constructions that adhere to foreign models, lacking architectural and constructive merit.

Migration to the main cities and return to the countryside, end up importing the architectural models of Lima’s peripheries, in turn derived from emergency architecture and a certain post-industrial global model, of use and abuse of reinforced concrete as a “noble” material, mirror glass, and banal lines (

Figure 44 and

Figure 45).

Land occupation has become so extensive that it undermines the thermal regulation inherent in this traditional construction. Materials and techniques that preserve accumulated knowledge are being supplanted, including sustainable adobe construction, simultaneously with the gradual replacement of traditional tile roofs with light-weight metal sheeting. This transition not only creates issues with climatic comfort but also intensifies fluctuations in temperature and humidity, exacerbating diurnal and nocturnal temperature variations. Furthermore, it compromises the structural integrity of the diaphragm formed by the tile roof, which stabilizes and restrains wall displacement during seismic events, thereby heightening the risk of structural failure and potential harm to occupants.

In addition, these interior open spaces are minimized or disappear, and with them the links of the domestic sphere of living with the landscape, and therefore the most intimate sense of belonging. Similarly, the climatic regulation that these spaces provide, and the links that they provide to the domestic space with the landscape, disappear under the idea of building the maximum possible number of interior spaces, even if they do not have basic architectural qualities. Land occupation has become so extensive that it undermines the thermal regulation inherent in this traditional construction.

Today, an intense process of destruction of traditional architecture is underway that replaces it with these “modern” constructions, without spatial qualities or bioclimatic function.

9. Applications and Limitations of the Research

The intensive ten years of continuous work undertaken on the Valley, from research projects and their transversalities with postgraduate courses at our university, among others, have produced, we believe, great and varied results, both from the academic and research point of view, and from the position, more importantly, of the real transformations on the place.

From a more abstract and invisible point of view, our presence in the area has been nourished by constant exchanges with the communities. From a more formal point of view, through various meetings and institutional workshops in the different municipalities of the Valley, we have collaborated with representatives of the communities, the State, and various professionals, in discussing progress and creating a joint vision of the Valley, with constant presentations and advances of results, subject to analysis and criticism by the inhabitants of the Valley and its most profound experts.

On the other hand, immersion in everyday life, the daily dynamics in the country-side and the villages, their festivities and encounters, through a friendly welcome by the inhabitants, have allowed us to understand better and better what the reality of the Valley is like. Outside the six-monthly week of intensive workshops, the students continued visiting the Valley for long periods, accompanying the inhabitants in their daily activities, or being accompanied by them in professional work in the Valley. The relationship with the inhabitants of the Valley has continued throughout the year, in joint work.

From a more pragmatic point of view, the joint work over all these years has produced concrete results of direct, or almost direct, application in the area, of which we could cite some, as illustrations.

Firstly, the presentation of the Valley on the World Heritage Tentative List, which is a tool for revaluation and conservation. This presentation was made as a result of the work with the community already mentioned.

On the other hand, our research was shown to the community through several meetings, one of the most important of which was the Traveling Exhibition entitled: Sondondo, living cultural landscape, which was exhibited in Lima and Cabana, in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and local municipalities.

We believe that our joint work with the community has allowed them to increasingly and concretely visualize the exceptional value of the territory and to understand the importance of its preservation as a development resource. Although we understand that the community is generally aware of the value of the place, what our work has allowed them to do is to generate more solid academic and professional paths so that this value can be realized, drawn, measured, and made visible to those who must generate the means for its protection.

On the other hand, the Master’s degree in which we participated has published a wide variety of research works on the Valley, with a diversity of solutions, from more analytical and basic research perspectives, to concrete proposals for architectural projects or designing tools that provide public policies with guidelines to intervene in the Valley from their own logic.

Similarly, our research project ended up being configured as a training space for students, who became involved in the subject beyond their undergraduate studies, proposing final year projects or postgraduate theses.

We believe that, in the medium and long term, this will not only mean the improvement of the Valley, but also a generation of students trained in landscape who can really influence the policies of intervention and protection of Peruvian cultural landscapes, and also, through their already realized stays abroad, bring lessons that the Peruvian territory can contribute to the global context.

In this sense of “knowledge transfer”, and specifically, products resulting from our research, such as the Inhabited Landscape Guide, the Vernacular Architecture Catalogue, and the determination of Landscape Units, as well as the surveying of maps and aerial photographs in the Valley, all placed at the service of the community (local, academic, and state), we hope that they will be a tool for future public policies.

Our idea is that, based on these materials, we can intervene through management plans, land use plans, urban–rural design projects, and architectural projects in the Valley. The great challenge in this phase is to find the financing, institutional ties, and legislative frameworks that allow us to intervene in an unstable political context with continuous threats to democratic management.

10. Conclusions

The Sondondo Valley is a culturally significant landscape, shaped by the unique characteristics of the Peruvian territory, the interplay of geographic, ecological, and environmental factors of notable interest, and the ancestral knowledge of Andean communities in land management and lifestyle creation, evident across various scales from architecture to territory.

The intricate connections, living strategies, and systems necessitate nuanced and vigilant intervention, grounded in accumulated knowledge that, through sustained presence and continuous interaction with the community, can be transformed into project tools facilitating conservation.

Our studies provide an interpretation of this location characterized by interdisciplinarity, knowledge integration, the intersection of territory and architecture, the multidimensionality of environmental, cultural, and social factors, and a forward-looking perspective aimed at achieving sustainable regional development.

We perceive architecture not merely as a structure, but as the creation of space encompassing territory, landscapes, towns, and buildings, viewing the constructed environment as a cohesive reality that reflects the profound connections of the community with its surroundings.

We contributed to the nomination of this area as a World Heritage site, recognizing that it embraces universal, unique, and representative values of the Andean region. The appreciation and preservation of this site as a living heritage regard the landscape as both a conservation resource and a means for development, enabling the continued inhabitation of the Valley in the contemporary context.