Participatory Drawing Methodology for Light in Architecture: Drawing Experienced Space

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- How can we analyse and make conclusions about these spatial drawings?

- 2.

- How can drawings support other methods?

- 3.

- Do the drawings need to be explained with words?

- 4.

- How can we use the findings from the drawings?

- 5.

- Does the method work better for professional sketchers than non-professionals?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Concepts, the Experienced Space, and the Light-Room

2.2. Sketching in Research

2.3. An Attentive Drawing Experience

2.4. Participatory Drawing

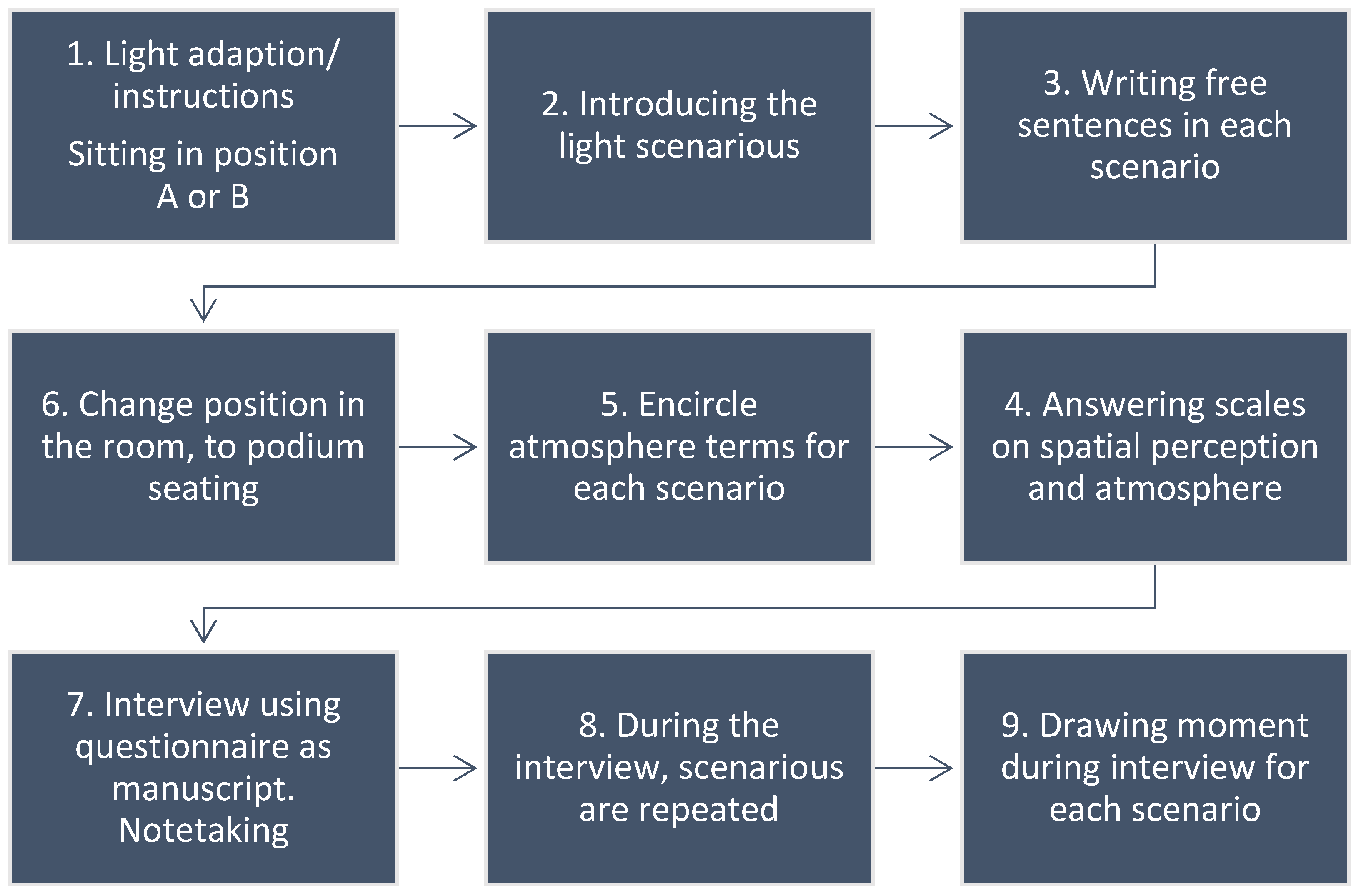

3. Materials and Methods

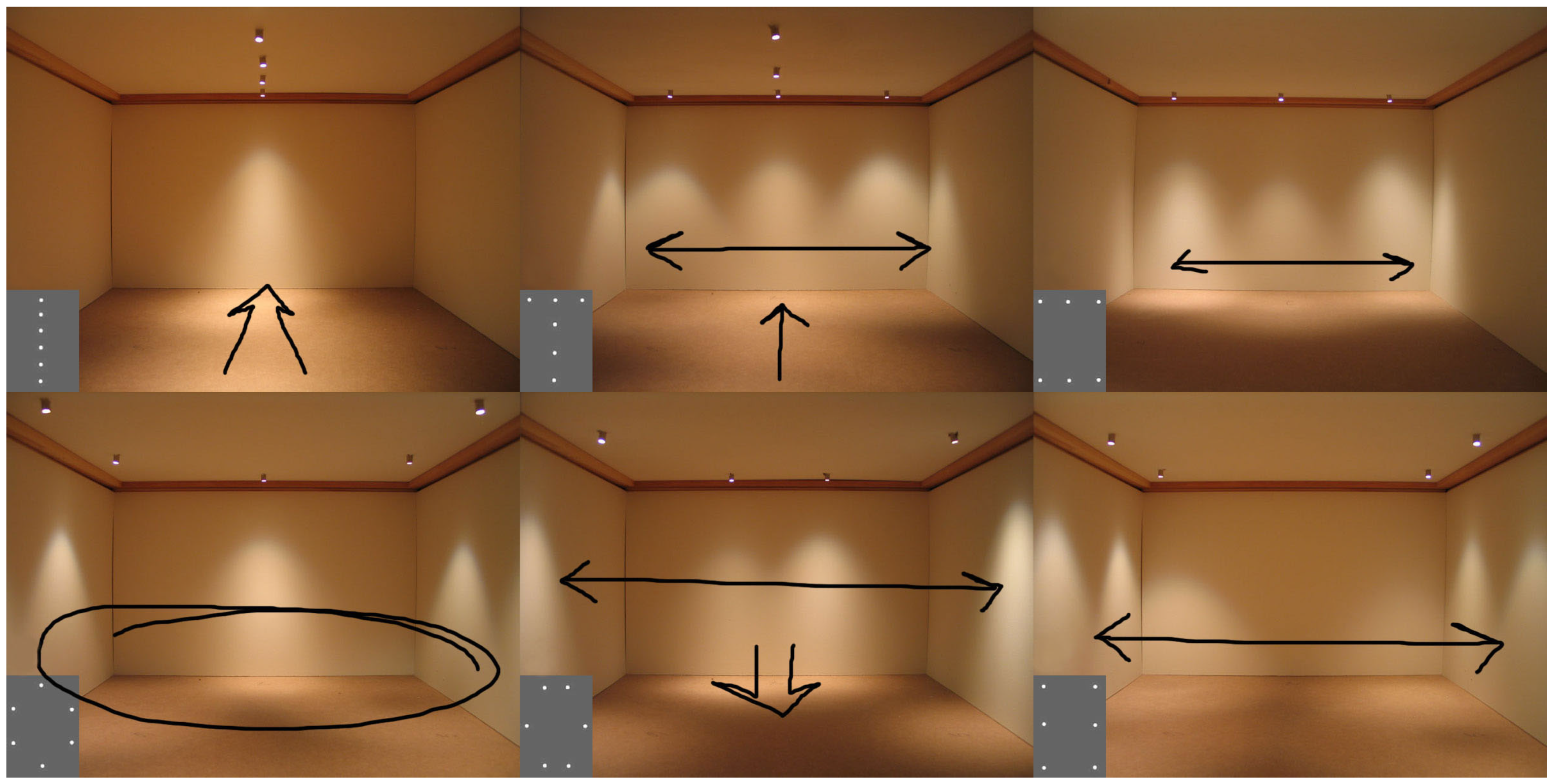

- The Lecture Scenario is a bright scenario with less ceiling emphasis and greater focus on the podium.

- The Picture-Showing Scenario is the darkest as it uses no wall lights. Only the recessed downlights are glowing weakly. The main light source is the overhead projector.

- The Auditory Scenario is the brightest and the most uniform scenario. It is the only scenario with upward-directed light.

- The Mood Scenario is rather dark, with wall emphasis and no directed light (no spotlight and no overhead projector).

Procedure for Analysing Empirical Data

4. Results

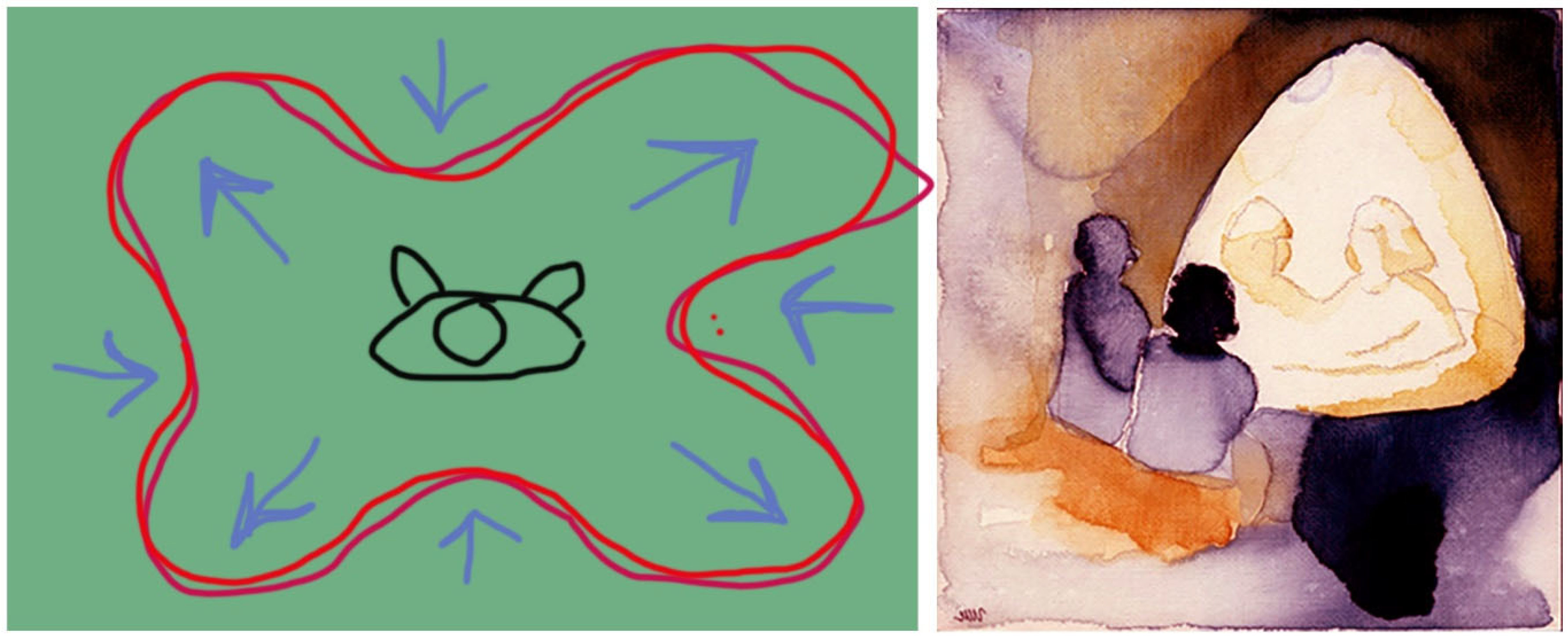

4.1. Sketches Exemplifying Spatial Concepts

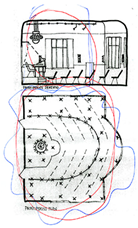

4.2. Overview of Drawing Findings

4.3. Interview Quotations from the Drawing Moment

Yes, it will be very easy. They will fill the room, both of them. … So actually, I’m lying a bit now. Actually, I should have pulled it [the line] over there because I… No, not so clearly. In such cases, it applies to the other one as well… I didn’t experience it clearly, I can say. I didn’t think about it before actually…Yes, there is no focus on anything here. Here, just as it is now, all places are equally good… Or important you could say…

The room-room is not so important here, and not prominent either. The light-room receives a much more important, larger role here. It is clearer that it is a light-room, that this is the light-room, and there is also another light-room, more diffuse on the sides. There is a kind of tension between this light-room and the other, more subdued light-room. The experienced rooms are like two different rooms, in a sort of way.

5. Discussion of Results

5.1. Sketching Interpretation

5.2. Professional Differences

6. Discussions of Methods

- What one experiences;

- What one draws;

- What the researcher interprets;

- What the reader grasps;

- The interpretation of the spatial aspects/bubbles and arrows.

7. Conclusions

7.1. How Can We Analyse and Make Conclusions About These Spatial Drawings?

7.2. How Can Drawings Support Other Methods?

7.3. Do the Drawings Need to Be Explained with Words?

7.4. How Can We Use the Findings from the Drawings?

7.5. Does the Method Work Better for Professional Sketchers than Non-Professionals?

7.6. Practical Considerations for Applying the Drawing Experienced Space Method

“I see you drew a line here—can you describe your thinking, especially since it differs from what you drew over there?”

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

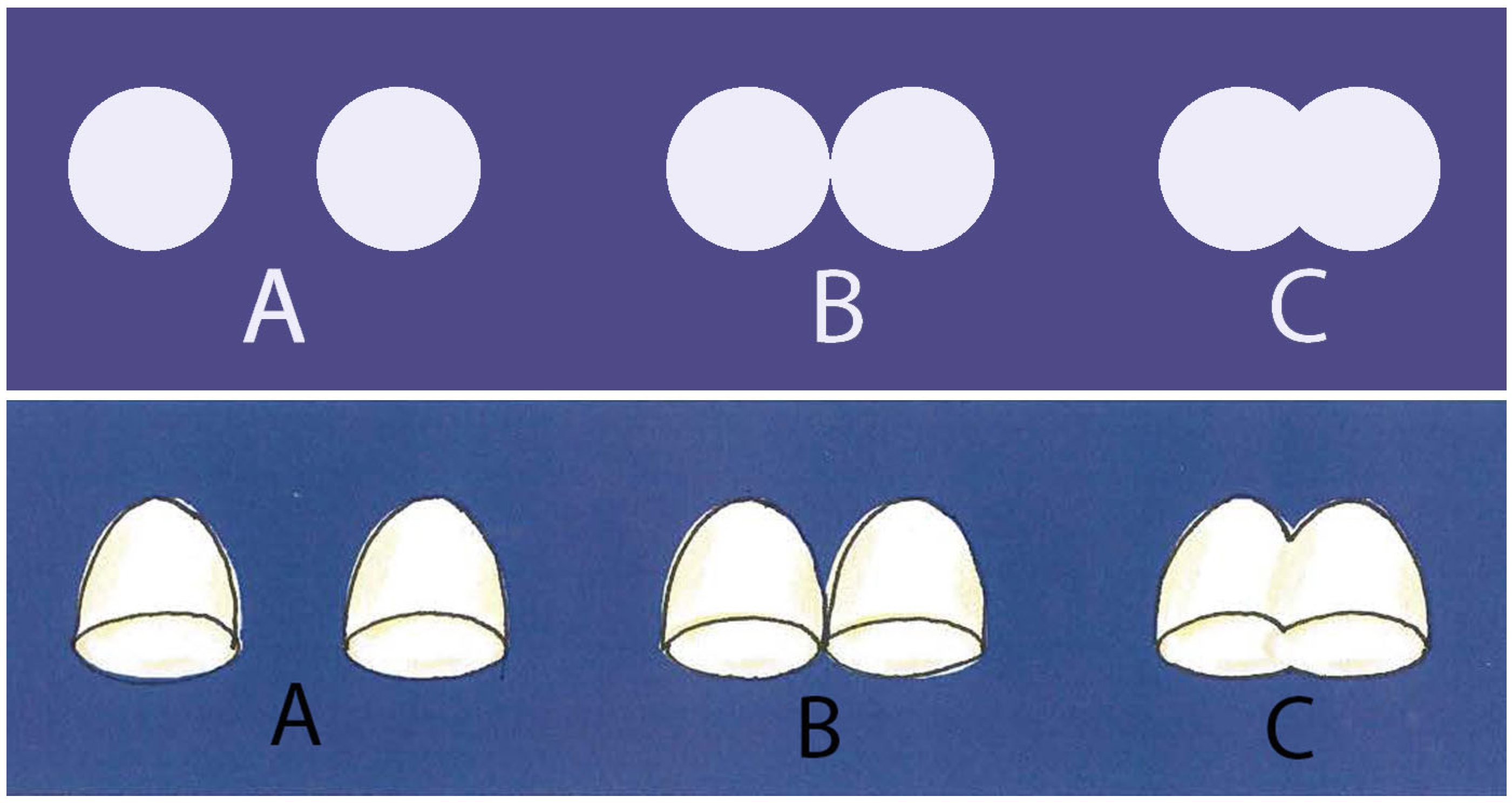

Appendix A. Patterns for Spatial Concepts

| Concepts | Explanation | Picture Example | Scenarios with Participant No. |

|---|---|---|---|

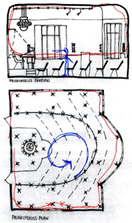

| Inwards | Arrows are pointing inwards, towards the podium. The figure shows the Lecture scenario, of Participant No. 4. |  | Lecture: 3, 4, 5, 6, 8,12, 13,14,15, 17, 18,19 and 21. Picture: 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21. Auditory: 3, 12 13, 17 and 21. Mood: 1, 8, 11, 13, 17, 18, 19 and 20. |

| Outwards | Arrows are pointing from the room centre outwards in the plan view. The figure shows the Auditory scenario, of Participant No. 18. |  | Lecture: 3, 5, 6, 19 and 20. Picture: 4 and 20. Auditory: 8, 11, 15, 17, 18, 19 and 21. Mood: 3, 4, 5,15 and 20. |

| Small | A smaller space (circle) is drawn inside the room, with a distinctly smaller size than the built room size. Also, participants’ other drawings matter for comparing the assessment of size. The figure shows the Picture scenario, of Participant No. 5. |  | Lecture: 5, 8, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18 and 20. Picture: 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 19 and 21. Auditory: - Mood: 1, 6, 14, 18 and 21. |

| Large | The experienced room bubble expands beyond or fills up the whole built room. Also, participants’ other drawings matter for comparing the assessment of size. The figure shows the Mood scenario of Participant No. 12. |  | Lecture: - Picture: 3, 12, 13, 15, 17 and 20. Auditory: 4, 5, 6, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19 and 21. Mood: 4, 5, 6, 12 and 20. |

| Concepts | Explanation | Picture Example | Scenarios with Participant No. |

|---|---|---|---|

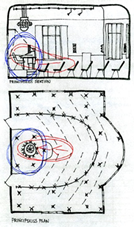

| Wide | Arrows are pointing outwards, in the widest room dimensions. Often the room bubble follows this direction. This pattern is also marked as outward. The figure shows the Lecture scenario, of Participant No. 3. |  | Lecture: 3 Picture: - Auditory: - Mood: 3, 5 and 20. |

| High | Height is shown on the section drawing either by the bubble’s shape drawn up and, or above the ceiling with a clear difference to other drawings, or height is shown through arrows pointing upwards. The figure shows the Auditory scenario, Participant No. 12. |  | Lecture: 1, 4, 17 and 19. Picture: 4, 12 and 15. Auditory: 3, 6, 12, 15 and 19, Mood: 6, 11 and 17. |

| Low | A low-height experience is either shown by a lower room bubble in the section drawing and/or is shown by arrows pointing downwards. The figure shows the Mood scenario of Participant No. 5. |  | Lecture: - Picture: 15 and 19. Auditory: - Mood: 1, 5, 15 and 19. |

| Concepts | Explanation | Picture Example | Scenarios with Participant No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centred | A room bubble is centred in the room. The figure shows the Auditory scenario, of Participant No. 5. |  | Lecture: - Picture: 20. Auditory: 5, 6. 12, 13, 17, 18 and 20. Mood: 1, 4, 14 and 17. |

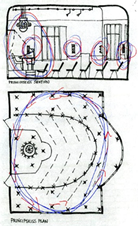

| Aligned | The experienced room extension fills the room and coincides with the built walls. Some participants exclude the bay window. Therefore, the experienced room is more angular. The figure shows the Auditory scenario, of Participant No.14. |  | Lecture: 21. Picture: - Auditory: 1, 4, 5, 8, 12, 13, 14, 18 and 21. Mood: - |

| Rooms within a room | Several participants draw “room bubbles” inside, freestanding from the physically built room. The figure shows the Auditory scenario, Participant No.11. |  | Lecture: 4, 6, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 and 19. Picture: 1, 6, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17 and 19. Auditory: 6, 11 and 12. Mood: 6, 8, 11, 13, 17, 18 and 19. |

| Scenario | Lecture | Picture | Auditory | Mood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

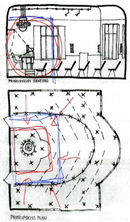

| Participant 4 Professional drawer |  |  |  |  |

| Participant 5 Professional drawer |  |  |  |  |

| Participant 6 Non-professional drawer |  |  |  |  |

| Participant 12 Non-professional drawer |  |  |  |  |

Appendix B. Comparison with Statistical Data

References

- Boyce, P. Editorial: The Divorce of the Art and Science of Lighting. Light. Res. Technol. 2017, 49, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K. A Different Type of Lighting Research—A Qualitative Methodology. Light. Res. Technol. 2017, 49, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P. Lighting Research for Interiors: The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning. Light. Res. Technol. 2004, 36, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, K.P. Architectural lighting design: A research review over 50 years. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.E.; Spencer, T.J.; Martyniuk, O.; Hendrick, C. Interim Study of Procedures for Investigating the Effect of Light on Impression and Behavior. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1973, 3, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R. Lighting as an Integral Part of Architecture. Coll. Art J. 1952, 12, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Socov, E. The movement of people toward lights. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1974, 3, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo Cortés, A.B.; Falcón Morales, L.E. Emotions and the Urban Lighting Environment: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billger, M. Rummet som färgernas mötesplats. In Forskare Och Praktiker Om Färg, Ljus, Rum; Fridell Anter, K., Ed.; Formas: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Billger, M. Colour in Enclosed Space: Observation of Colour Phenomena and Development of Methods for Identification of Colour Appearance in Rooms. Doctoral Dissertation, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kronqvist, A. Lighting Design in Computerised Offices. Doctoral Dissertation, Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Architecture, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, P. Human Factors in Lighting, 1st ed.; Applied Science Publishers Ltd.: Essex, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, P. Human Factors in Lighting, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schielke, T. The Language of Lighting: Applying Semiotics in the Evaluation of Lighting Design. Leukos 2019, 15, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugar, A.M. The role of poetics in architectural lighting design. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell Anter, K.; Billger, M. Colour research with architectural relevance: How can different approaches gain from each other? Color Res. Appl. 2010, 35, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.A. Psychological processes influencing lighting quality. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 2001, 30, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wänström Lindh, U. Light Shapes Spaces: Experiences of Distribution of Light and Visual Spatial Boundaries. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Gothenburg Art Monitor, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Häggström, C. Förhållandet mellan forskning och konstnärligt arbete—Om skissande som metod. Nord. J. Archit. Res. 1997, 4, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Molander, B. Kunskap i Handling; Bokförlaget Daidalos: Gothenburg, Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Skipetari, A.; Nijhuis, S. Drawing in architectural lighting design. Magazine for Professional Lighting Design no. 80/81 Dec 2011/Jan 2012. pp. 42–45. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287331755_Drawing_in_architectural_lighting_design (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Lyon, P. Using Drawing in Visual Research: Materializing the Invisible. In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wänström Lindh, U.; Jägerbrand, A.K. Perceived Lighting Uniformity on Pedestrian Roads: From an Architectural Perspective. Energies 2021, 14, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S.; Chapman, L.; The Morgan Centre Sketchers. Observational Sketching as method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 21, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, H. Sketching as a Research Tool for Understanding Sacred Places. Int. Res. Cent. Jpn. Stud. 2001, 2001, 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajaniemi, H.; Luusua, A.; Teirilä, M.; Österlund, T.; Tanska, T. Experiencing Participatory and Communicative Urban Lighting through LightStories. In Proceedings of the MAB‘12: Proceedings of the Media Architecture Biennale Conference: Participation, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, 15–17 November 2012; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wänström Lindh, U.; Billger, M.; Aries, M. Experience of Spaciousness and Enclosure: Distribution of Light in Spatial Complexity. J. Sustain. Des. Appl. Res. 2020, 8, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, A.; Camgöz Olguntürk, N.; Yener, C.; Güvenç, D.; Gürçinar, Y. Impact of Lighting Arrangements and Illuminances on Different Impressions of the Room. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3476–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent Prozman, J.; Houser, K.W. On the Relationship Between Object Modeling and the Subjective Response. Leukos 2005, 2, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.C.; Cassidy, B.; Kurr, J. Room preference as a function of architectural features and user activities. J. Appl. Psychol. 1978, 63, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Castell, C.; Oberfeld, D.; Hecht, H. The Effect of Furnishing on Perceived Spatial Dimensions and Spaciousness of Interior Space. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokharaei, S.; Nasar, J.L. Perceived Spaciousness and Preference in Sequential Experience. Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnkil, H.; Fridell Anter, K.; Klarén, U. Colour and Light: Concepts and Confusions; Aalto University Publication Series: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Matusiak, B.; Fridell Anter, K.; Arnkil, H.; Klarén, U. PERCIFAL Method in Use: Visual Evaluation of Three Spaces. In Proceedings of the AIC Midterm Meeting, Interaction of Colour & Light in the Arts and Sciences, Zürich, Switzerland, 7–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arnkil, H.; Fridell Anter, K.; Klarén, U.; Matusiak, B. PERCIFAL: Visual Analysis of Space, Light and Colour. In Proceedings of the AIC Midterm Meeting, Interaction of Colour & Light in the Arts and Science, Zürich, Switzerland, 7–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M. Light-Zone(s): As Concept and Tool. An Architectural Approach to the Assessment of Spatial and Form-Giving Characteristics of Daylight. In Proceedings of the ARCC/EAAE International Research Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 30 June 2006; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M. Lysrum-Som Begreb Og Redskab. Doctoral Dissertation, Kunstakademiets Arkitekturskole, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wänström Lindh, U.; Billger, M. Light Distribution and Perceived Spaciousness: Light Patterns in Scale Models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzell, A. Något Om … Liten Skissbok Om Det Upplevda Rummet; Rundqvists Boktryckeri: Göteborg, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Branzell, A. Management of sequential space experiences. In Proceedings of the Future of Endoscopy, Proceedings of the 2nd European Architectural Endoscopy Association Conference, Vienna, Austria, 30 August–1 September 1995; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Branzell, A. Att Notera Rumsupplevelser; Statens råd för byggnadsforskning: Stockholm, Sweden, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Acking, C.-A.; Küller, R. Volymupplevelser i Rum: Inledande Studier; Arbetsrapport 1; Tekniska högskolan i Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, K.W.; Tiller, D.K.; Bernecker, C.A.; Mistrick, R.G. The Subjective Response to Linear Flourescent Direct/Indirect Lighting Systems. Light. Res. Technol. 2002, 34, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberfeld, D.; Hecht, H.; Gamer, M. Surface Lightness Influences Perceived Height. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2010, 63, 1999–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J.E.; Mills, S.M. Architectural Lighting Graphic’s; Reinhold Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselgren, S. Man’s Perception of Man-Made Environment; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselgren, S. The Language of Architecture; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 1969; Volumes 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkvist, J.; Gärling, T. Visually Apparent Restricted Space as a Function of Number of Screens and Brightness Level Delineating an Empty Space. In Experimental Studies of Architectural Perception; Hesselgren, S., Ed.; National Swedish Building Research: Stockholm, Sweden, 1971; Document D2. [Google Scholar]

- James, F. “Sketch and Talk”—Drawing Lines Between Humans, the Interior and Stuff. Design Methodologies for Well-Being in Prisons, Forensic Psychiatric Hospitals, and Special Residential Youth Homes. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Gothenburg Gothenburg Art-Monitor, Göteborg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Causey, A. Drawing flies: Artwork in the field. Crit. Arts 2012, 26, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Drawn to That Moment. New Soc. 1976, 37, 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel, C.; Van Wezemael, J. Drawing as a Qualitative Research Tool: An Approach to Field Work from a Social Complexity Perspective. Tracey J./Draw. Knowl. 2012, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Theron, L.; Mitchell, C.; Smith, A.; Stuart, J. Picturing Research: Drawing as Visual Methodology; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen, J.; Hakoköngäs, E. Drawing as a method of researching social representations. Qual. Res. 2022, 23, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, M.; Masley, S.; Allison-Love, J. Drawing as a research tool: What does it add? In Proceedings of the RCN International Research Conference, Oxford, UK, 5–7 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jellema, P.; Annemans, M.; Heylighen, A. Drawing the researcher into data: Drawing as an analythical tool in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 1398–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, M. Drawing as a Research Tool: Making and understanding in art and design practise. Stud. Mater. Think. 2014, 10, 1–12. Available online: https://www.materialthinking.org/papers/147 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- James, F. “Sketch and Talk”: An ethnographic design method opening closed institutions. In Proceedings of the Cumulus—Open Design for Everything, Hong Kong Design Institute, Hong Kong, China, 21–24 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K. Making Sense of Place: Mapping as a Multisensory Research Method. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Townscape; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension; Peter Smith, Doubleday & Company: Gloucester, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Ings, W. Enstasy: Immersive drawings as a design process. In Proceedings of the Nordic Design. Research Conference: Experiments in Design Research, Copenhagen, Denmark; Malmö, Sweden, 9–12 June 2013; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kashanipour, J. The Gradual Gaze: Drawing as a practice of Ethnographic Description. Anthropol. Humanism 2021, 46, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literat, I. “A Pencil for your Thoughts”: Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küller, R. A Semantic Model for Describing Perceived Environment; D 12:1972; National Swedish Institute for Building Research: Stockholm, Sweden, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wänström Lindh, U.; Billger, M. Light Topography and Spaciousness in the Urban Environment. Nord. J. Archit. Res. (NJAR) 2021, 33, 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wänström Lindh, U. Distribution of Light and Atmosphere in an Urban Environment. J. Des. Res. 2013, 11, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickström, G.; Bendix, T. The “Hawthorn effect”—What did the original Hawthorn studies actually show? Scand. J. Environ. Health 2000, 26, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Interpreting Interviews; Sage Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflective Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Illumination | Lecture | Picture-Showing | Auditory | Mood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceiling light | 75% | <25% | 100% | 25% |

| Wall lamps | 75% | Off | 100% | 25% |

| Brass track | 75% | Off | 100% | 25% |

| Crown up | Off | Off | 100% | 25% |

| Crown down | 75% | Off | 100% | 25% |

| Spotlight | On | Off | Off | Off |

| Overhead light | On | On | Off | Off |

| Average illuminance, É_avg | 62 lux | 29 lux | 44 lux | 12 lux |

| Maximum illuminance, É_max | 252 lux | 141 lux | 83 lux | 26 lux |

| Minimum illuminance É_min | 21 lux | 5 lux | 29 lux | 4 lux |

| Uniformity Uo | 0.6 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 0.67 |

| Scenarios/ Concepts | Inw. | Outw. | Small | Large | Wide | High | Low | Cent | Aligned | Mult. Rooms |

| Lecture | 13 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Picture | 13 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Auditory | 5 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 3 |

| Mood | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wänström Lindh, U. Participatory Drawing Methodology for Light in Architecture: Drawing Experienced Space. Buildings 2025, 15, 2278. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132278

Wänström Lindh U. Participatory Drawing Methodology for Light in Architecture: Drawing Experienced Space. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2278. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132278

Chicago/Turabian StyleWänström Lindh, Ulrika. 2025. "Participatory Drawing Methodology for Light in Architecture: Drawing Experienced Space" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2278. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132278

APA StyleWänström Lindh, U. (2025). Participatory Drawing Methodology for Light in Architecture: Drawing Experienced Space. Buildings, 15(13), 2278. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132278