4.1. Main Findings

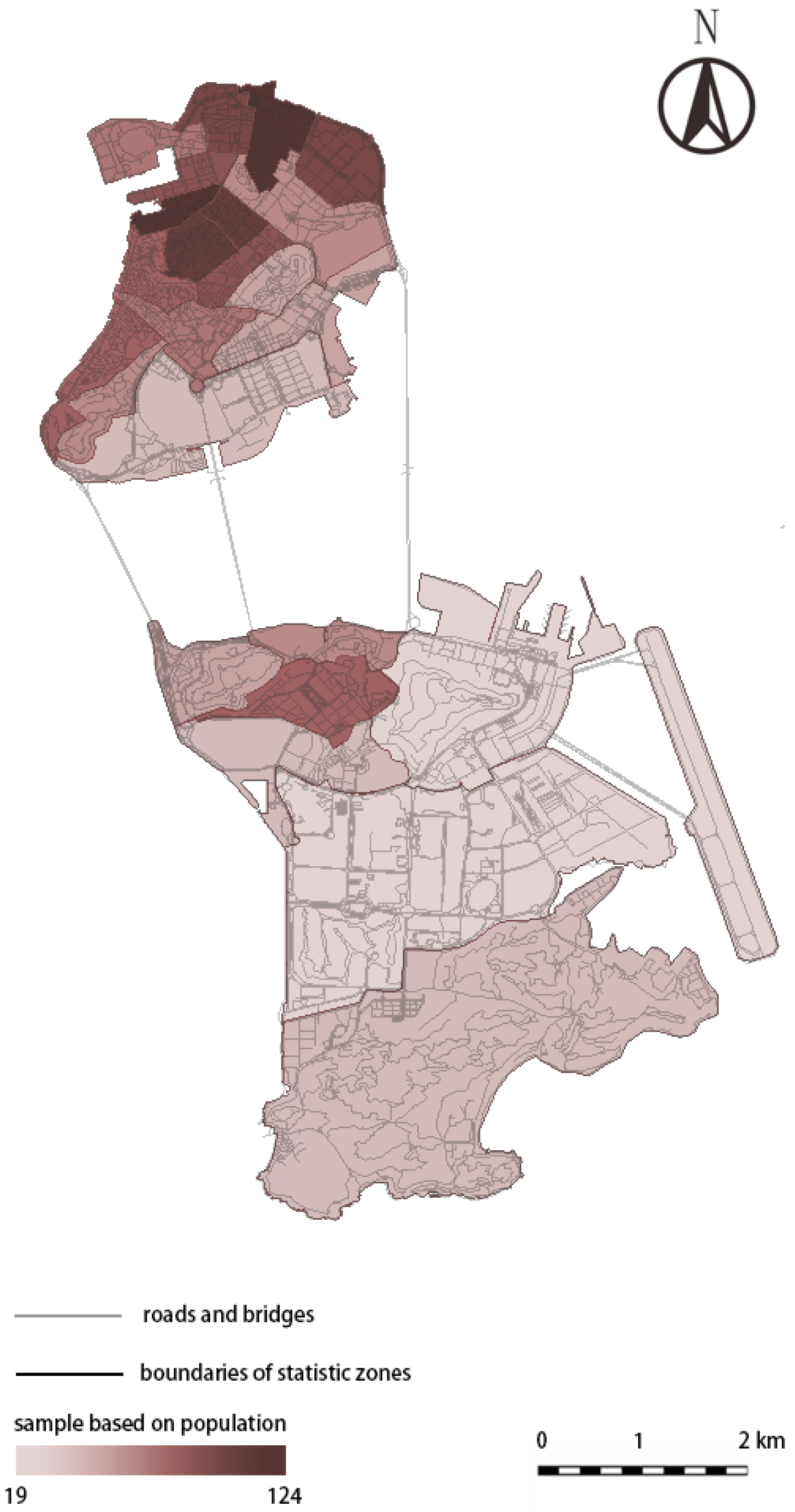

The main findings are based on a new theoretical framework that explores the impact of the social and morphological significance of the architectural environment on subjective well-being. This directly addresses Research Objective (1) by revealing the mechanisms through which the built environment influences well-being. Determinants of well-being have been identified. In addition, the intrinsic pathway between environmental factors and well-being was also considered. Different models were established using statistical dimension partitioning methods. By comparing eight models, the impact path of the built environment on well-being is revealed.

The results indicate that in terms of morphology, the most intuitive aspect is that the number of facilities within the statistical partition directly and significantly affects well-being. In addition, land use diversity, income background diversity, and education background diversity, which are socioeconomic indicators, also have a profound impact on well-being. The intersection density, road network density, and number of bus stops, which are three indicators related to walking accessibility, have a complete mediating effect on health satisfaction.

First, morphological variables require discussion. The following observations were derived from cross-sectional survey data and objective built environment data obtained via GIS:

(1) There is a significant correlation between intersection density and residents’ well-being, but after adding individual family attributes as control covariates, this correlation disappears. After adding health satisfaction as a mediator variable, this association reappears. This indicates that the variable of intersection density has a deep correlation with health satisfaction and affects residents’ well-being through health satisfaction.

(2) Road network density does not show any correlation with well-being in Models 1 and 2, but it becomes significant after incorporating social satisfaction and health satisfaction. This result indicates that its association with well-being is actually strongly correlated with social satisfaction and health satisfaction, and it should not be assumed that there is a connection between road network density and well-being.

(3) The regression results for service facilities, entertainment facilities, catering facilities, and office facilities are similar and can be discussed together. Service facilities do not have a direct correlation with well-being, and after adding personal family attributes to Model 2, the impact on well-being becomes significant. The significance of service-oriented facilities is also highlighted in Guo et al.’s article [

35]. This is a normal phenomenon because service facilities include various venues, gas stations, and other facilities that are closely related to individual choices. Entertainment facilities, catering facilities, and office facilities all demonstrate a strong correlation with well-being. Lin et al. point out that access to a hospital, supermarket, and gym enhanced people’s well-being, corresponding to service facilities, retail facilities, and leisure facilities [

36]. The distribution of these four facilities also affects well-being through entertainment satisfaction, social satisfaction, and job satisfaction. Although there is no correlation between service facilities and office facilities and health satisfaction, catering and entertainment facilities show a significant correlation with health satisfaction. Work facilities and service facilities have a positive impact on well-being, indicating that the rationality of urban spatial facility configuration has a considerable impact on well-being, which is similar to the conclusions of articles studying the walkability of urban facilities [

37].

(4) The number of public transportation stops has a positive impact on well-being, and the impact is significant when social satisfaction and health satisfaction are used as mediating variables, indicating that the rationality of urban spatial facility configuration has a significant impact on well-being. A study in Singapore also noted that safe and convenient transportation infrastructure is often linked to people’s health [

10].

(5) There is no evidence to suggest that building density and population density are related to resident well-being, which is consistent with some previous research findings [

36], while some studies targeting elderly individuals have found a strong correlation between building density and well-being [

37]. Possible reasons for these different research conclusions may be the selection of research units (statistical zones) or differences in research subjects (all age groups and only elderly people).

For the socioeconomic factors, the following observations can be made:

(1) The Shannon index of educational background does not show a direct correlation with well-being in Models 1 and 2 but instead shows a negative correlation with entertainment satisfaction, job satisfaction, and social satisfaction in Models 3–5. This result indicates that as the difference in educational background increases, life satisfaction tends to decrease, and the improvement in well-being often occurs under the premise of a close educational background. Pei [

38] indicates that the level of education has a significant positive impact on subjective well-being, and the widening gap in educational background may weaken the sense of social equity, which aligns research findings.

(2) The Shannon index of income background shows a significant correlation with well-being in all models. Similar to the Shannon index of educational background, the coefficients are also negative, indicating an increase in income differentiation and a decreasing trend in life satisfaction and well-being. For territories, a higher index signifies greater socioeconomic fragmentation—where neighborhoods exhibit extreme heterogeneity in household incomes. Moreover, the Shannon index of income background is fully mediated by four types of life satisfaction, indicating that the diversification of income levels will affect the well-being of regional residents. Filip Fors Connolly et al. [

39] finds that in wealthier countries, the correlation between income and life satisfaction decreases as per capita GDP increases, but income disparities may affect well-being through relative deprivation mechanisms. Pei’s research also suggests that the weakening effect of family economic status on happiness after exceeding the average level further supports the negative impact of income inequality [

38].

(3) The Shannon index of land use is significant in Models 1 and 2. After adding the four types of life satisfaction as covariates, the significance decreases. Only when entertainment satisfaction is used as a mediator variable does it remain significant. This indicates that land use diversity directly affects the well-being of residents and is not influenced by life satisfaction. However, there is no significant relationship between population density and building density and well-being. The above results show that the overall socioeconomic development of statistical zones has a significant impact on individual residents, and differences in social diversity lead to certain differences in well-being levels. Guo demonstrates that land use change may indirectly enhance residents’ well-being through policies, rather than solely through economic intermediaries [

39]. Similarly, land use diversity may directly affect residents’ experiences through resource availability and spatial functional differences; the distribution of entertainment facilities reflects this point [

13].

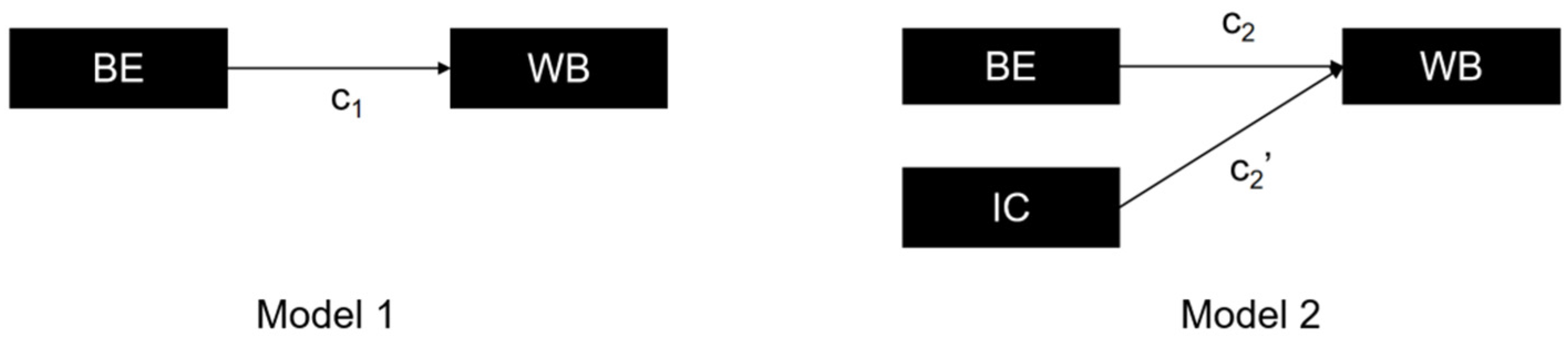

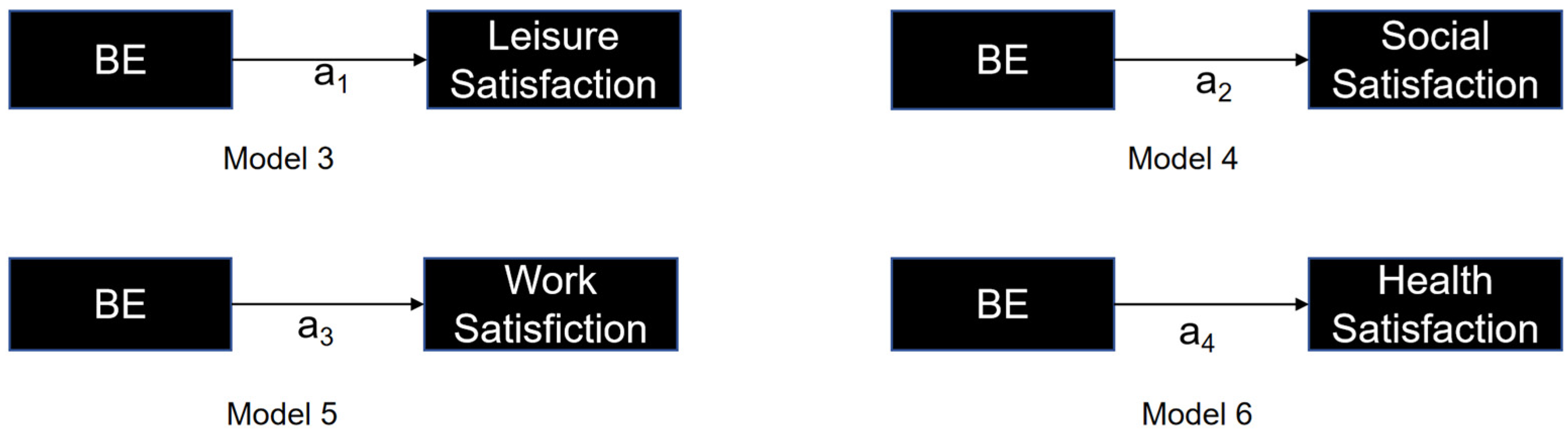

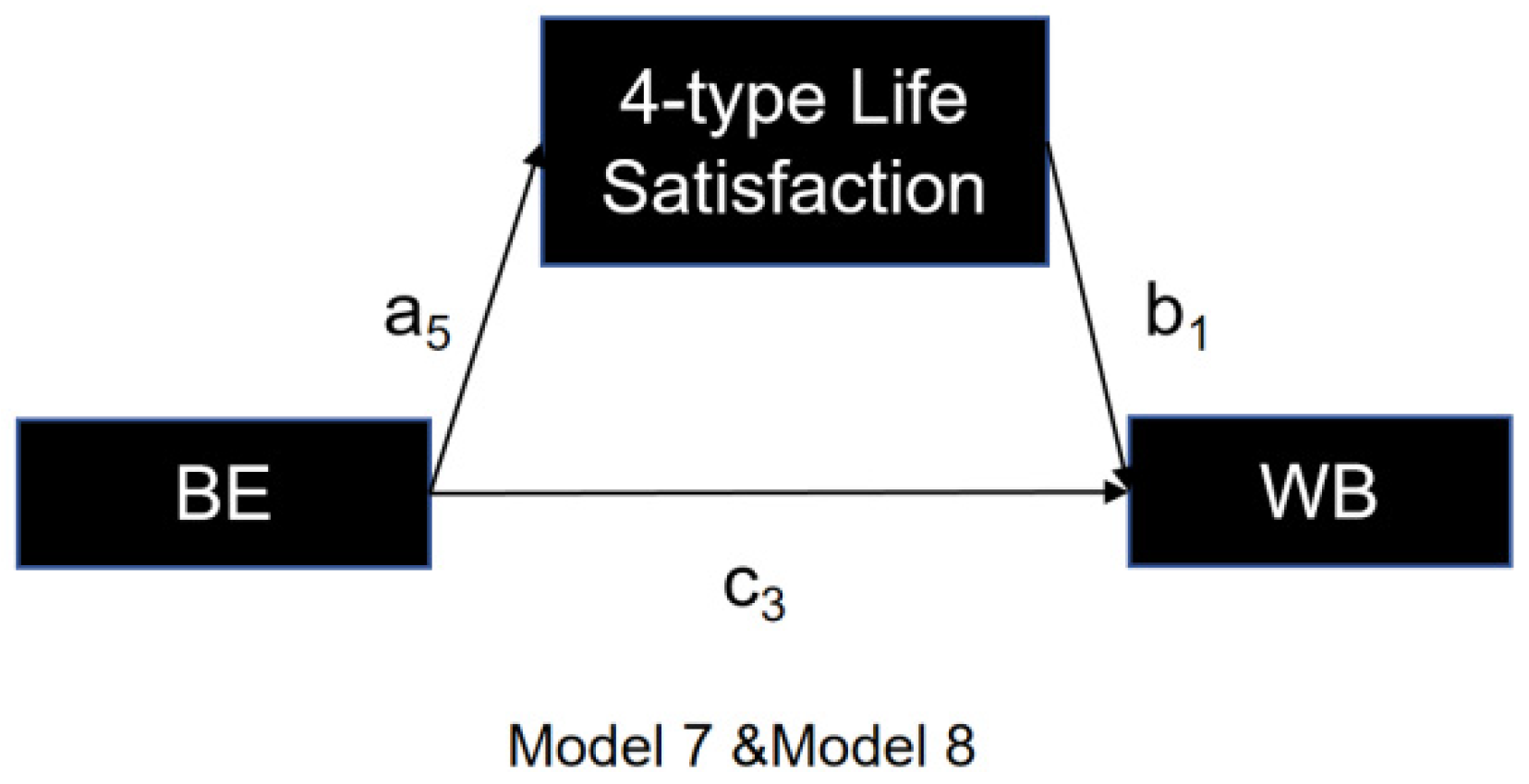

Concerning Research Objective (2) on mediation pathways, the role of mediating variables within the causal pathway was further elucidated. Model 1 revealed the direct effect of independent variables on the dependent variable, while Models 3–6 demonstrated the impact of independent variables on mediating variables. Models 7–8 showed the effects of independent variables on the dependent variable when controlling for four mediators. Five scenarios emerged:

Variables exhibiting significance in both Model 1 (significant c path,

Figure 2) and Model 7 (significant c’ path,

Figure 2) without meeting Model 1 criteria demonstrated partial mediation;

If a built environment variable showed non-significance in Models 3/4/5/6 (non-significant a path,

Figure 3) or Model 8 (non-significant b path,

Figure 4), this suggests insufficient evidence for its association with residents’ well-being;

Complete mediation occurred when variables were non-significant in Model 1 but significant in Model 7, provided they avoided Scenario 1 conditions;

Suppression effects were identified when variables transitioned from non-significant in Model 1 to significant in Model 7, with opposing signs between the product of a coefficients (Models 3–6) and c’ coefficients (Model 7);

Non-significant variables in both Model 1 and Model 7 with consistent coefficient signs indicated no substantial association.

The key findings are revealed below:

Complete mediation: Intersection density (health satisfaction), bus stop count (health and social satisfaction), and income diversity Shannon index (all outcomes).

Partial mediation: Service facilities (excluding health satisfaction), retail facilities (all outcomes), catering facilities (all outcomes), office facilities (excluding health satisfaction), recreational facilities (all outcomes), land use Shannon index (all outcomes), education diversity Shannon index (excluding health satisfaction), and unemployment rate (all outcomes).

Non-significant associations: Building density, road network density, and population density.

Therefore, a novel classification system for environmental effects was developed. The summary of these scenarios is presented in

Table 11.

4.2. Life Satisfactions: The Core Bridge Between Built Environment and Happiness

1. Health satisfaction: the core link between environmental stress and health perception

Health satisfaction is the most widely mediated pathway through which the built environment affects happiness. For example, intersection density, through its complete mediating effect on health satisfaction (rather than direct impact), suggests that high-density traffic environments may weaken residents’ perception of health through chronic stress (such as noise and safety hazards), thereby reducing their sense of well-being. Similarly, the number of bus stops serves as a dual mediator between health and social satisfaction, suggesting that the accessibility of public transportation may affect both physical health and social connectivity, but further validation of its interactive effects is needed. It is worth noticing that some variables (such as service facilities and educational Shannon index) were not mediated by health satisfaction and may be related to the differential impact of facility types on health behavior.

2. Social satisfaction: a key channel for spatial design to promote social capital

Social satisfaction is prominent in the partial mediation of the number of bus stops and service facilities, supporting the theoretical hypothesis of “space promotes social interaction”. The high accessibility of bus stops may strengthen social networks by increasing chance encounters (such as neighborhood interactions), while service facilities (such as community centers) provide physical carriers for collective activities. However, the partial mediating effect of retail and catering facilities on all satisfaction levels (including society) suggests that the business environment may affect happiness through a dual pathway: both directly improving quality of life through convenience and indirectly enhancing satisfaction through promoting socialization. This is consistent with the view of commercial spaces as social incubators in the “third place” theory.

3. Job and Entertainment Satisfaction: Environmental Diversity Supports Pathways

Job and entertainment satisfaction are not common traditional intermediary pathways, as they highlight the widespread impact of the built environment on psychological needs. The Shannon index of income diversity, through the complete mediation of all four satisfaction levels, indicates that an economic mixed environment may enhance happiness in multiple dimensions through employment opportunities (job satisfaction), leisure choices, access to health resources (health satisfaction), and community inclusiveness (social satisfaction). In contrast, the partial mediating effect of land use diversity (Shannon index) points to its direct support for work entertainment balance: such as the integration of work and residence to reduce commuting pressure. These findings expand the existing research’s understanding of the “environment happiness” pathway, suggesting the need to go beyond the health framework and incorporate the perspectives of career development and leisure equity.

4. Implications for non-significant variables: threshold effects and situational dependence of environmental indicators

The non-significance of variables such as building density and road density contradicts some research [

25], possibly due to a non-linear relationship: moderate density promotes convenience, while excessive density leads to congestion pressure. In addition, these variables may indirectly act through unmeasured mediators such as sense of security and aesthetic experience, and further testing is needed in conjunction with geographical contexts such as city level.

This systematic mediation analysis clarifies the complex pathways through which built environment characteristics influence residents’ well-being, highlighting both direct and mediated relationships. The current research has several limitations that can be addressed in future studies. First, empirical analysis based on questionnaire data may suffer from self-assessment bias and issues of non-dependence. Like many other statistical models, the ordinary least squares (OLS) model used in the current study can reveal only statistical relationships within sample data. The results based on statistical models test the credibility of causal relationships in the empirical world, which may differ from causal relationships in the real world. Due to limitations in research conditions, cross-sectional data were used in this study, which may lead to limitations in the research conclusions. Future research may strengthen the causality of research through empirical sampling methods (ESMs). Also, a limitation of our modeling strategy is that the more focused models (3–8) do not include the full set of controls examined in Model 2. While this allows for cleaner tests of specific hypotheses and avoids over-controlling, it means that the estimates in these models could potentially be influenced by unobserved or omitted confounders. This study considers only limited influences on well-being. Other factors, such as tourism and psychological satisfaction, may also play a role [

17]. Including more elements in the model could provide better insights into the factors influencing well-being.