Challenges and Strategies for the Retention of Female Construction Professionals: An Empirical Study in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key Literature Findings

2.1. Theories of Female Retention in Construction

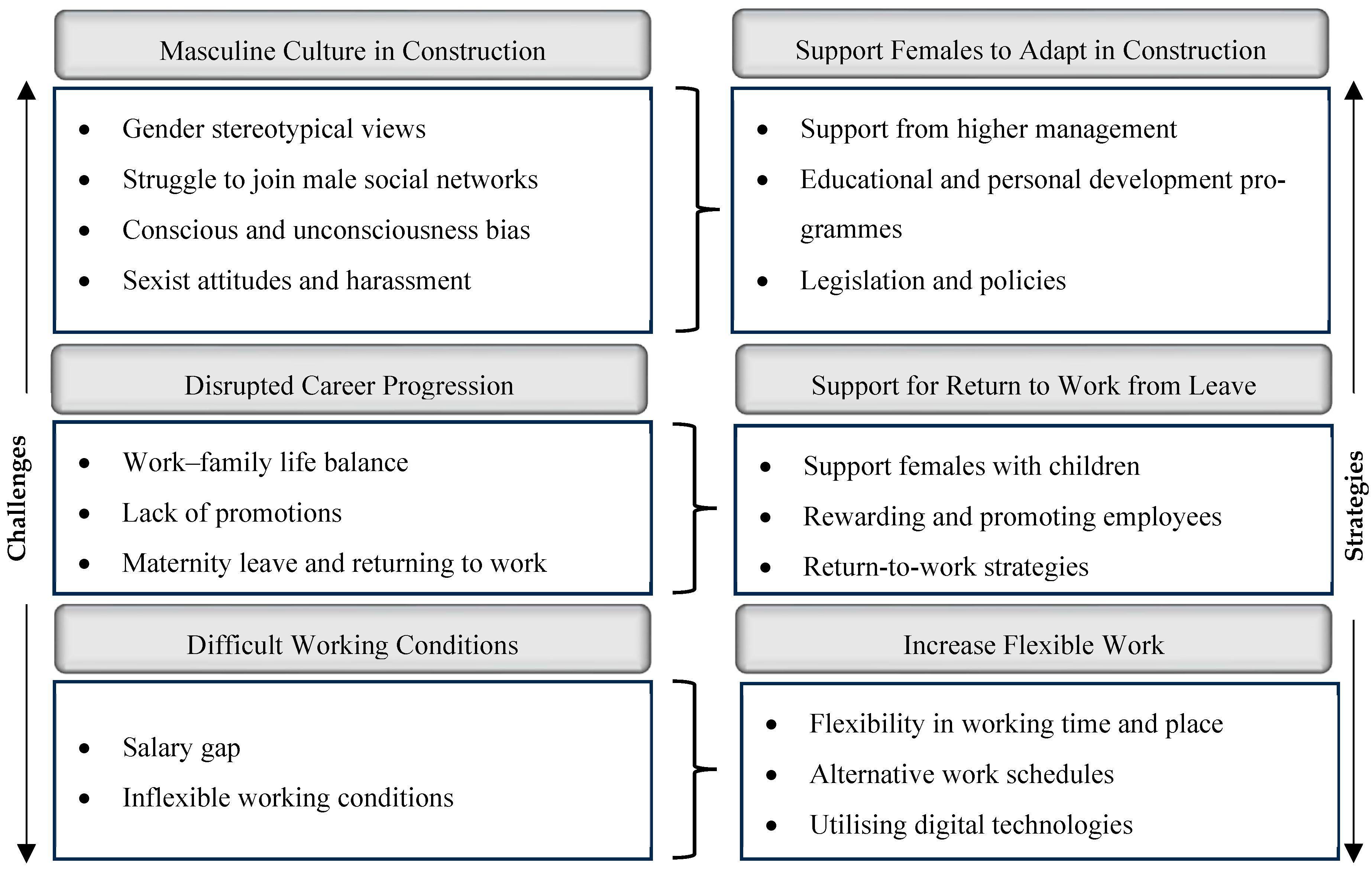

2.2. General Challenges for Female Construction Professionals

- Masculine Culture in Construction

- Disrupted Career Progression

- Difficult Working Conditions

2.3. General Strategies to Retain Female Construction Professionals

- Support Females to adapt in Construction

- Support for Return to Work from Leave

- Increase Flexible Work

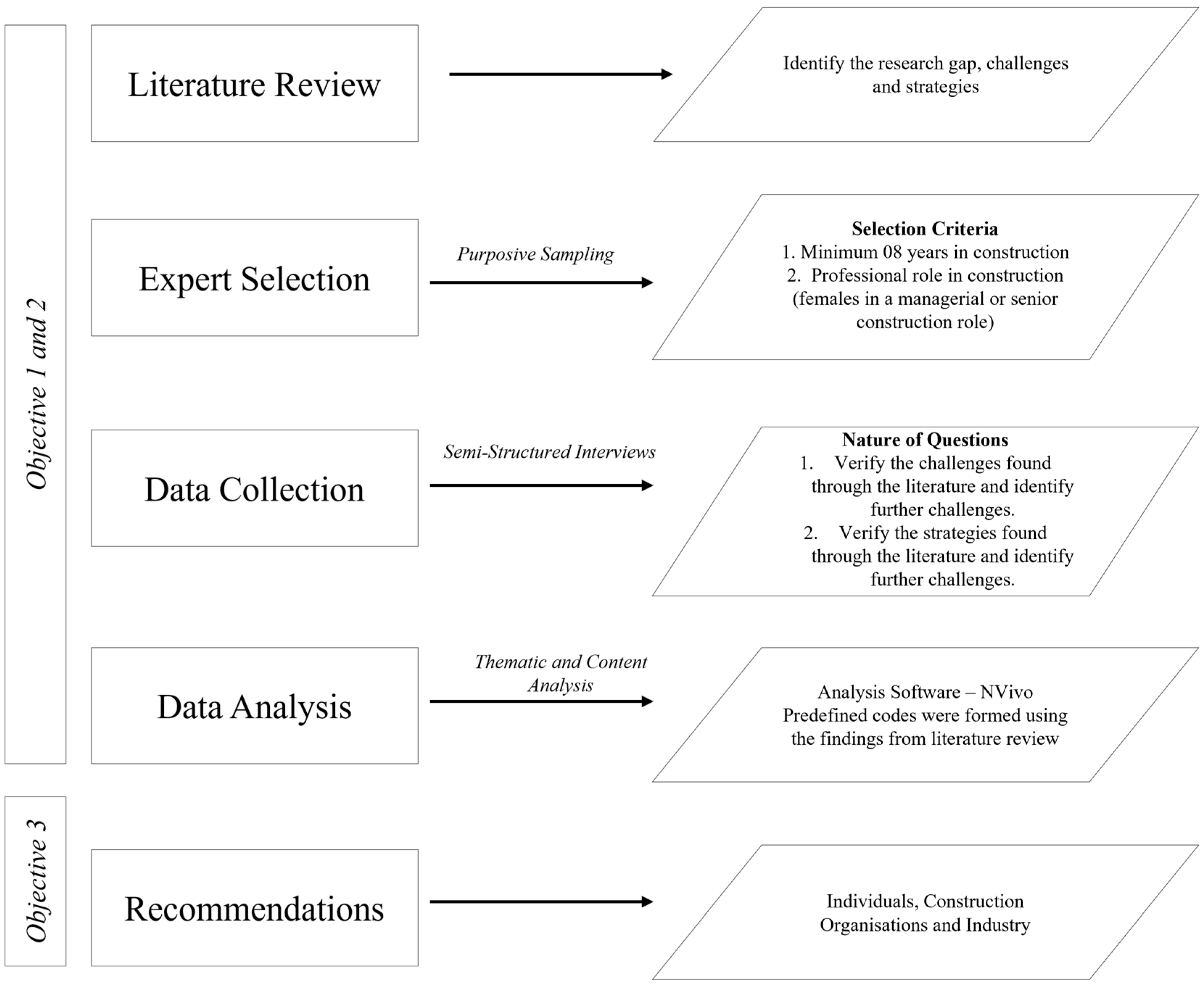

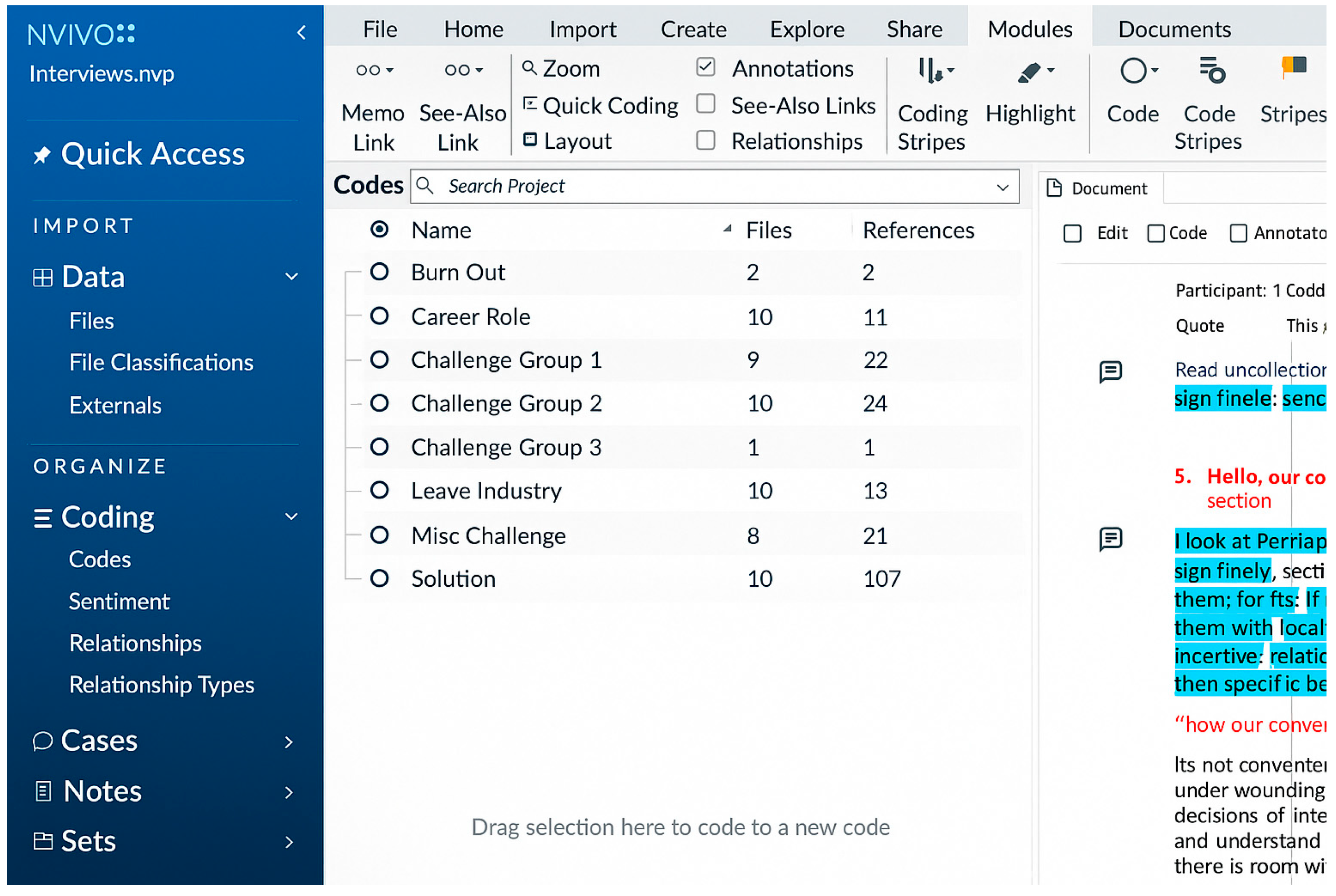

3. Research Method

4. Empirical Findings and Discussion

4.1. Respondents’ Details

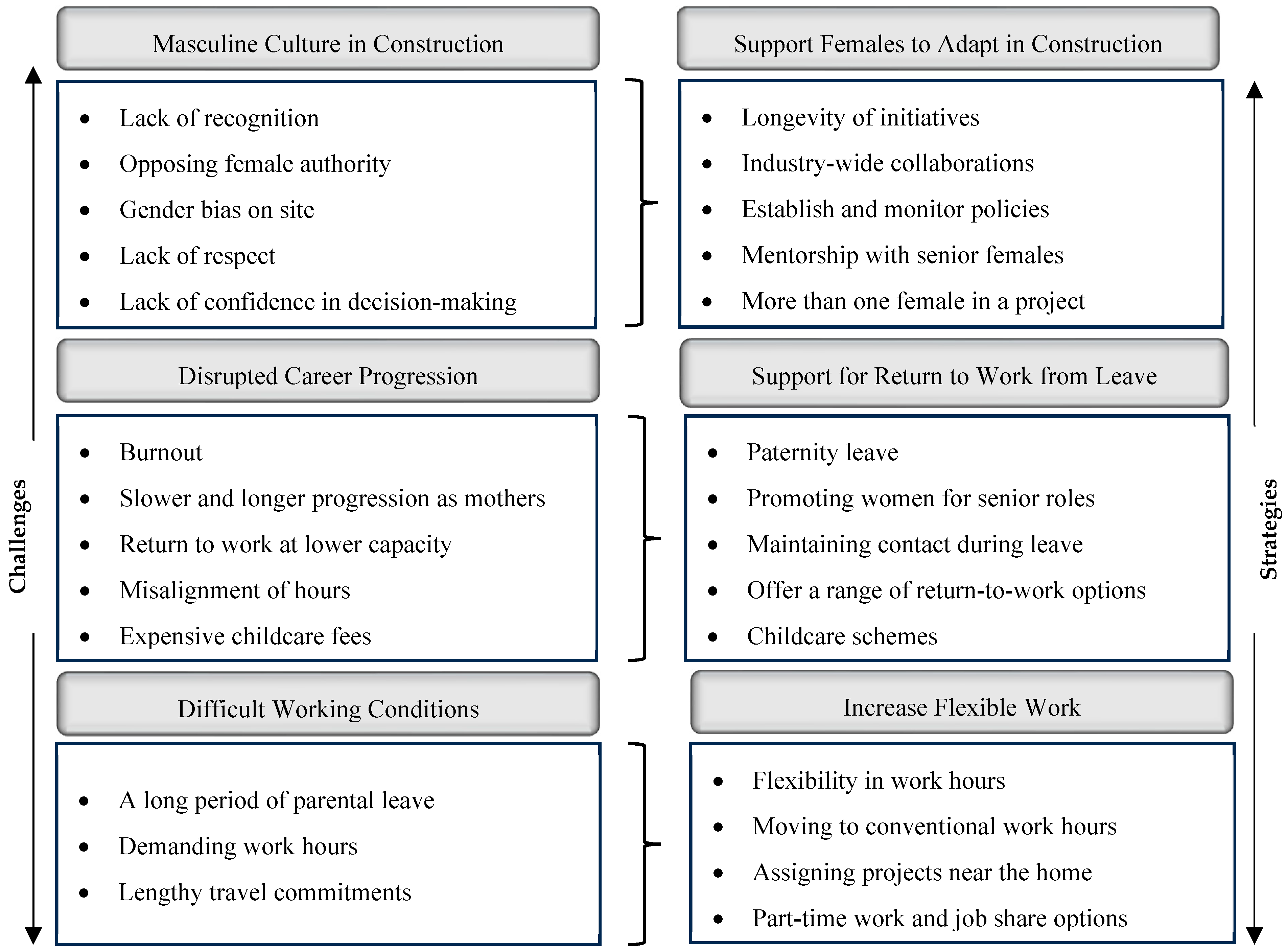

4.2. Specific Challenges Faced by Female Construction Professionals

- Masculine Culture in Construction

- Disrupted career progression

- Difficult Working Conditions

4.3. Specific Strategies to Retain Female Construction Professionals

- Support females to Adapt in Construction

- Support for Return to Work from Leave

- Increase Flexible Work

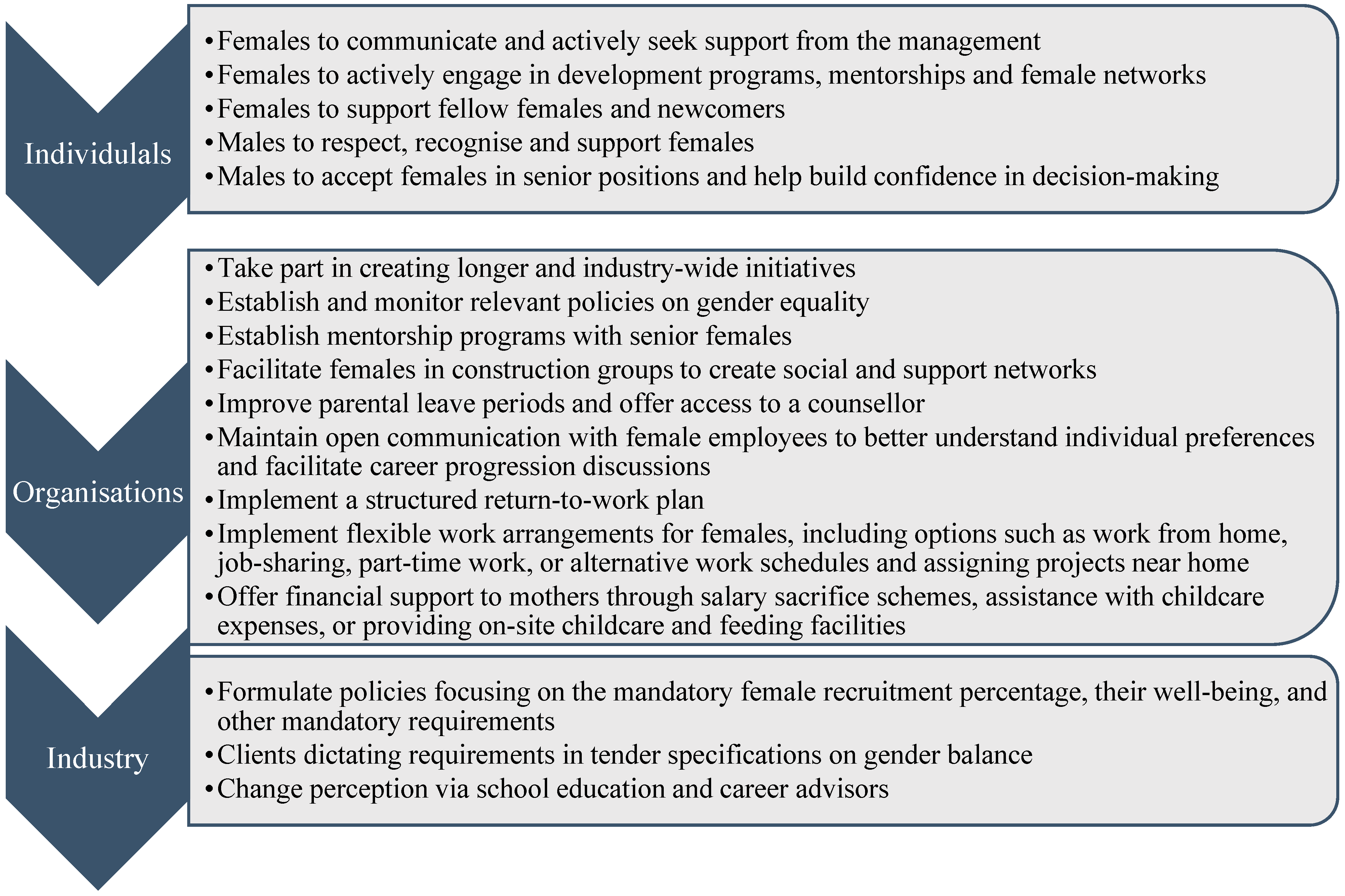

5. Recommendations Emerging from the Research Findings

6. Research Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Policy Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francis, V.; Michielsens, E. Exclusion and inclusion in the Australian AEC industry and its significance for women and their organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mito, T. Developing the Construction Industry for Employment-Intensive Infrastructure Investments; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_policy/---invest/documents/publication/wcms_734235.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Perrenoud, A.J.; Bigelow, B.F.; Perkins, E.M. Advancing women in construction: Gender differences in attraction and retention factors with managers in the electrical construction industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A. Plights of Women Construction Workers in Bangladesh. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Aminian, E.; Stewart, I. Barriers Contributing to the Underrepresentation of Women in the Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Gender Research, Porto, Portugal, 10–11 April 2025; pp. 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, A.; Oyeyipo, O.; Ojelabi, R.; Patience, T.-O. Balancing the female identity in the construction industry. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 24, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISC (Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC)). National Industry Insights Report; Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC): Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australia Bureau of Statistics. Gender Indicators, Australia. 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/gender-indicators-australia/latest-release (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Wang, C.C.; Mussi, E.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Analysing gender issues in the Australian construction industry through the lens of empowerment. Buildings 2021, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Ali, M.; Crawford, L. What do women want? An exploration of workplace attraction and retention factors for women in construction. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokbolat, S.; Karaca, F.; Durdyev, S.; Calay, R.K. Construction professionals’ perspectives on drivers and barriers of sustainable construction. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 22, 4361–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. 2019–2020 Annual Report; Department of Education, Skills and Employment: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cassells, R.; Duncan, A.S. ; Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (BCEC), Curtin Business School. Gender Equity Insights 2020: Delivering the Business Outcomes; Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (BCEC), Curtin Business School: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Skills Commission. Labour Market Insights: Construction Managers. Available online: https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/occupation-profile/construction-managers?occupationCode=1331 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Master Builders Australia. Breaking Ground: Women in Building and Construction; Master Builders Australia: Fyshwick, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gorde, S. A Study of Employee Retention. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2019, 6, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Del Puerto, C.; Guggemos, A.; Shane, J. Exploration of strategies for attracting and retaining female construction management students. In Proceedings of the 47th ASC Annual International Conference Proceedings, Omaha, NE, USA, 6–9 April 2011; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- NAWIC. The NAWIC Journal 2019. Available online: https://nawic.com.au/common/Uploaded%20files/2019_nawic_journal_online-2%20(1).pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Maurer, J.A.; Choi, D.; Hur, H. Building a diverse engineering and construction industry: Public and private sector retention of women in the civil engineering workforce. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, V.; Layton, D.; Prince, S. Diversity Matters; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wangle, A. Perceptions of Traits of Women in Construction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, N. The Rise of Women in Construction: Why It’s Critical, Especially in Field Leadership. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/blogs/construction/the-rise-of-women-in-construction-why-its-critical-especially-in-field-leadership/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Tangara, F. Women in Construction. Available online: https://evercam.com.au/blog/women-in-construction/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchiri, S.; Kamm, J.D. Navigating barriers faced by women in leadership positions in the US construction industry: A retrospective on women’s continued struggle in a male-dominated industry. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Andamon, M.M. Does gender really matter? A closer look at early career women in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbaripour, A.N.; Tumpa, R.J.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Zhang, W.; Yousefian, P.; Camozzi, R.N.; Hon, C.; Talebian, N.; Liu, T.; Hemmati, M. Retention over attraction: A review of women’s experiences in the Australian construction industry; challenges and solutions. Buildings 2023, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, B.; Senaratne, S.; Mirza, O.; Camille, C. Overcoming challenges faced by female construction management graduates: An exploratory study in Australia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Ghosh, A.; Mahmood, M.N.; Thaheem, M.J. Scientometric review of the twenty-first century research on women in construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: Lessons from the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, E.; Strachan, G. Women at work! Evaluating equal employment policies and outcomes in construction. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2015, 34, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V. What influences professional women’s career advancement in construction? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.E.; Hon, C.K.; Xia, B.; Lamari, F. Challenges, success factors and strategies for women’s career development in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salignac, F.; Galea, N.; Powell, A. Institutional entrepreneurs driving change: The case of gender equality in the Australian construction industry. Aust. J. Manag. 2018, 43, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, T.; Far, H.; Gardner, A. Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.; Feng, S. Early career women in construction: Are their career expectations being met? Constr. Econ. Build. 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. The gendered dimensions of informal institutions in the Australian construction industry. Gend. Work. Organ. 2020, 27, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H. Changes in job situations for women workforce in construction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E.; Ali, M. Insights into ineffectiveness of gender equality and diversity initiatives in project-based organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P.; Galea, N. Why Australian female high school students do not choose construction as a career: A qualitative investigation into value beliefs about the construction industry. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Holdsworth, S.; Scott-Young, C.M.; Sandri, K. Resilience in a hostile workplace: The experience of women onsite in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Liu, X.; Lim, B.T.H. The experiences of tradeswomen in the Australian construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E.; Ali, M.; Tootoonchy, M. Influence of Work–Life Programs on Women’s Representation and Organizational Outcomes: Insights from Engineering and Construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40, 04024005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Sandri, O. Gender Bias in the Australian Construction Industry: Women’s Experience in Trades and Semi-Skilled Roles. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Ding, Y.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Yang, Z. Career progression of female and male managers in the Australian construction industry: A comparative analysis using LinkedIn data. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, B.F.; Bilbo, D.; Mathew, M.; Ritter, L.; Elliott, J.W. Identifying the most effective factors in attracting female undergraduate students to construction management. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2015, 11, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye-Nimo, E.; Wood, H.; Collison, J. Complexity of women’s modern-day challenges in construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 2550–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. Women’s Progression in the Workplace, a Rapid Evidence Review for the Government Equalities Office; Government Equalities Office: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dainty, A.R.J.; Bagilhole, B.M.; Neale, R.H. A grounded theory of women’s career under-achievement in large UK construction companies. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, N.D.O.C. Building Commission NSW Women in Construction Report; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, U.B.; Sánchez, Y.A.; Pagan, J.P.M.; Ballón, W.C.; Jara, O.B.; Astete, R.A. Women and glass ceilings in the construction industry: A review: Las mujeres y los techos de cristal en la industria de la construcción: Una revisión. South Fla. J. Dev. 2021, 2, 4775–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, L.; Harris, K.; Stewart, R.; Thomas, A.; McDermott, P. Barriers to women in the UK construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2010, 17, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurjao, S. The Changing Role of Women in the Construction Workforce; CIOB: Ascot, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, E.F. Protean organizations: Reshaping work and careers to retain female talent. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Astor, E.; Román-Onsalo, M.; Infante-Perea, M. Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Oliver, A.; Blaviesciunaite, A. The changing nature of workplace culture. Facilities 2014, 32, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.L.; Sexton, M. Career journeys and turning points of senior female managers in small construction firms. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndweni, M.P.; Aghaegbuna, O.U.O. The need investigate career progression of female professional employees in the South African construction industry. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABCC. Your Rights and Responsibilities; Sexual Harassment. Available online: https://www.palmscheme.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-09/Sexual%20harassment%20-%20English.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Scott-Young, C.; Sandri, K. Women in Construction: Exploring the Barriers and Supportive Enablers of Wellbeing in the Workplace; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, H.; Carter, N.; Silva, C. Why men still get more promotions than women. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 80–85, 126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, M.; Stoltz, E. Employees’ satisfaction with retention factors: Exploring the role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Australia’s Gender Pay Gap Statistics. Available online: https://www.wgea.gov.au/publications/australias-gender-pay-gap-statistics#:~:text=Currently%2C%20Australia’s%20national%20gender%20pay,using%20data%20from%20the%20ABS.&text=%241%2C591.20%20compared%20to%20men’s%20average,earned%20%24255.30%20less%20than%20men (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Richard, B.; Travis, H.; Adrian, T. The Pay Gap: Pay Inequality but Pay Equity Found in the Construction Industry. J. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 19, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Australia’s Gender Equality Scorecard. Available online: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019-20%20Gender%20Equality%20Scorecard_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Perera, B.; Ridmika, K.; Wijewickrama, M. Life management of the quantity surveyors working for contractors at sites: Female vs male. Constr. Innov. 2022, 22, 962–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Lin, J. Career, family and work environment determinants of organizational commitment among women in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D.; Wulff, E.; Bamberry, L.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Jenkins, S. Negotiating gender in the male-dominated skilled trades: A systematic literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King Lewis, A.; Shan, Y. Persistence of women in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adogbo, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Ibrahim, Y. Development of a framework for attracting and retaining women in construction practice. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 20, 99. [Google Scholar]

- NAWIC. The NAWIC Journal 2021. Available online: https://nawic.com.au/Site/Site/Publications/NAWIC-Journal.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Schmidt, E.-M. Flexible working for all? How collective constructions by Austrian employers and employees perpetuate gendered inequalities. J. Fam. Res. 2022, 34, 615–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E. Female underrepresentation in project-based organizations exposes organizational isomorphism. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2018, 37, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Humbert, A.L. Discourse or reality? “Work-life balance”, flexible working policies and the gendered organization. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2010, 29, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Lew, E.J.Y. Strategies to recruit and retain generation Z in the built environment sector. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V.; Lingard, H.; Prosser, A.; Turner, M. Work-family and construction: Public and private sector differences. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Zhou, Z.; Manu, P.; Li, N. Falling risk analysis at workplaces through an accident data-driven approach based upon hybrid artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. Saf. Sci. 2025, 185, 106814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D.A. Doing Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limna, P. The Impact of NVivo in Qualitative Research: Perspectives from Graduate Students. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Jiao, X.; Qiu, X.; Xu, A. Investigating the impact of time allocation on family well-being in China. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 25, 981–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Granrose, C.S.; Rabinowitz, S.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of work-family conflict among two-career couples. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 34, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, B.L.; Arditi, D.; Balci, G. Women in construction management. CMAA eJournal 2009, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Focused Research Themes | Sources | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galea et al. [30] | French and Strachan [31] | Francis [32] | Rosa et al. [33] | Salignac, Galea and Powell [34] | Bryce, Far and Gardner [35] | Oo, Lim and Feng [36] | Galea et al. [37] | Oo and Lim [38] | Wang, Messi and Sunindijo [9] | Baker, French and Ali [39] | Carnemollo and Galea [40] | Turner et al. [41] | Francis and Michielsens [1] | Oo, Liu and Lim [42] | Ghanbaripour et al. [27] | Baker et al. [43] | Holdsworth, Turner and Sanddri [44] | Zhang et al. [26] | Wells et al. [28] | Yan et al. [45] | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||

| √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Respondent ID | Experience | Current Career Role | Previous Career Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 20 years | State design manager |

|

| R2 | 28 years | Construction manager |

|

| R3 | 15 years | Service manager |

|

| R4 | 31 years | National sector lead for architect |

|

| R5 | 09 years | Senior project engineer |

|

| R6 | 23 years | Project manager |

|

| R7 | 15 years | Chief financial officer |

|

| R8 | 14 years | Partner at a consulting firm |

|

| R9 | 15 years | Partner at a consulting firm |

|

| R10 | 16 years | Project manager |

|

| R11 | 09 years | Site engineer |

|

| R12 | 15 years | Contract administrator |

|

| R13 | 08 years | Safety officer |

|

| R14 | 27 years | Project manager |

|

| Challenges | |

| Literature Findings | Interview Findings |

| Masculine Culture in Construction | |

| Gender stereotypical views | Lack of recognition |

| Struggle to join male social networks | Opposing female authority |

| Conscious and unconscious biases towards females | Gender bias on site |

| Sexist attitudes and harassment | Lack of respect |

| Lack of role models and mentors | Lack of confidence in decision-making |

| Lack of females on site | |

| Disrupted Career Progression | |

| Work–family life balance | Burnout |

| Lack of promotions | Slower and longer progression as mothers |

| Taking maternity leave and returning to work | Return to work at lower capacity |

| Misalignment of hours | |

| High childcare fees | |

| Lack of on-site feeding facilities | |

| Difficult Working Conditions | |

| Salary gap | A long period of parental leave |

| Inflexible work conditions | Demanding work hours |

| Lengthy travel commitments | |

| Strategies | |

| Literature Findings | Interview Findings |

| Support Females to Adapt in Construction | |

| Support from higher management | Duration of initiatives |

| Educational and personal development programmes | Industry-wide collaborations |

| Legislation and policies | Establish and monitor policies |

| Mentorship programmes | Mentorship with senior females |

| More than one female in a project | |

| Creating female social networks | |

| Support for Return to Work from Leave | |

| Support females with children | Paternity leave |

| Rewarding and promoting employees | Promoting females into senior roles |

| Return-to-work strategies | Maintaining contact during parental leave |

| Offer a range of return-to-work options | |

| Childcare scheme | |

| Feeding facilities | |

| Increase Flexible Work | |

| Flexibility in working time and place | Flexibility in work hours |

| Alternative work schedules | Moving to conventional work hours |

| Utilising digital technologies | Assigning projects near home |

| Work from home options | Part-time work and job share |

| 9-day fortnight shift | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senaratne, S.; Jayakodi, S.; Pascoe, R.D.; Atkins, A. Challenges and Strategies for the Retention of Female Construction Professionals: An Empirical Study in Australia. Buildings 2025, 15, 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132187

Senaratne S, Jayakodi S, Pascoe RD, Atkins A. Challenges and Strategies for the Retention of Female Construction Professionals: An Empirical Study in Australia. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132187

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenaratne, Sepani, Shashini Jayakodi, Ryan David Pascoe, and Annalise Atkins. 2025. "Challenges and Strategies for the Retention of Female Construction Professionals: An Empirical Study in Australia" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132187

APA StyleSenaratne, S., Jayakodi, S., Pascoe, R. D., & Atkins, A. (2025). Challenges and Strategies for the Retention of Female Construction Professionals: An Empirical Study in Australia. Buildings, 15(13), 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132187