Abstract

The Hashim Chalbi house, a historic private residence with notable architectural features located within Erbil Citadel—a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2014—was turned into a museum. This study utilizes space syntax analysis (depth maps) to explore the spatial configuration of the Hashim Chalbi house, aiming to evaluate its potential and provide guidance for conservation strategies that maintain its architectural and cultural integrity as a museum. Space syntax offers both a theoretical and analytical tool to map and interpret the spatial formation of heritage buildings. A commonly recognized limitation has been the lack of broader-scale spatial analyses of houses that can shed light on social and cultural interaction. This approach aims to provide a better analysis to inform conservation and restoration.

1. Introduction

The city of Erbil (Arbela), first mentioned during the 23rd century BC, later became one of Assyria’s most important centers and capitals [1,2]. Archaeological research has postulated the continuity of settlement since prehistoric times. Although it was advised to preserve the districts, rapid economic and demographic growth resulted in rules that accepted new districts as an addendum to the system. The Erbil Citadel, the last continuously inhabited mudbrick citadel in Kurdistan, enclosed by a historic wall [3,4], became the focus of a revitalization program initiated in 2007 by the Kurdistan regional government and the city of Erbil. This included establishing museums and a cultural heritage institute. Following its designation as a UNESCO world heritage site in 2010, international collaboration involving twenty-five countries aimed to preserve its unique historical fabric [5,6]. As an architectural icon reflecting the region’s socio-cultural structure, the citadel contains numerous traditional dwellings. The Hashim Chalbi house exemplifies the complex spatial and functional relationships typical of traditional Iraqi domestic architecture. Erbil Citadel is an artistic expression that reflects the region’s rich cultural heritage as an unparalleled residential center that houses the most ancient surviving part of Erbil city [7]. The significance of this study lies in its potential guidance in the process of conservation and rehabilitation of Erbil Citadel, as well as its contribution to the comprehensive understanding of the relationship between architectural space and social forces and urban identity through a historical process. The Hashim Chalbi house showcases a distinctive architectural typology shaped by climatic, social, and cultural influences. Its design includes a central courtyard that organizes interconnected private and public areas [3,5], representing the characteristics of traditional Ottoman housing in the region. This house was constructed in the early 20th century and is recognized for its architectural design and historical significance in hosting social events. Its structure uses unique materials and construction methods, featuring brickwork and elements spanning multiple phases [6].

2. Research Questions and Objectives

Space syntax theory provides a theoretical framework, and its associated tools offer an analytical strategy for mapping and analyzing the spatial organization of historical buildings. This paper uses space syntax techniques to investigate the architectural and spatial context of the Hashim Chalbi house and provides informed conservation strategies in support of its architectural and cultural significance. This research aims to answer the following questions:

- -

- Firstly, how does a space syntax analysis of the Hashim Chalbi house provide insights into its potential as a museum and its conservation?

- -

- Second, how does the Hashim Chalbi house’s spatial configuration, analyzed using space syntax metrics (e.g., integration, connectivity, and visibility), reflect its historical socio-cultural functions?

- -

- Third, what insights do this spatial analysis provide into the house’s suitability and potential challenges for adaptive reuse as a museum, respecting the building’s heritage?

- -

- Finally, how can these findings guide the development of targeted, knowledgeable, and focused conservation and design strategies while enhancing the museum’s functionality as a public museum?

This study aimed at achieving the following objectives:

- -

- Analyze Spatial Configuration:

This study analyzes the spatial layout of the Hashim Chalbi house using analytical techniques. It explores the design of interior spaces, architectural boundaries between private and public areas, and their alignment with concepts of privacy and social interaction.

- -

- Investigate Spatial Properties:

This study analyzes the house’s spatial properties—connectivity, accessibility, visibility, and movement patterns—using a depth map analysis. These metrics reveal the connections between spaces and their roles in social and cultural activities.

- -

- Recommend Conservation Strategies:

This study aims to recommend strategies for preserving and adaptively reusing the Hashim Chalbi house while respecting its architectural and cultural integrity. This research seeks sustainable methods for integrating historical heritage into contemporary uses by examining the house’s spatial and social dimensions.

3. Theoretical Framework

Architectural Analysis of Hashim Chalbi House

The morphology of Erbil Citadel is unique and forms an organic relationship with its topography and the other elements of the city. The architectural vocabulary of an identifiable style is described in certain visual forms, rhythm, and composition, as well as in cohesive structural solutions and material use [4].

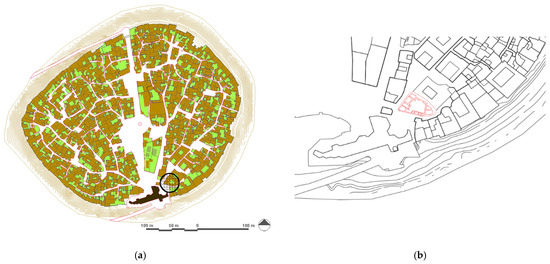

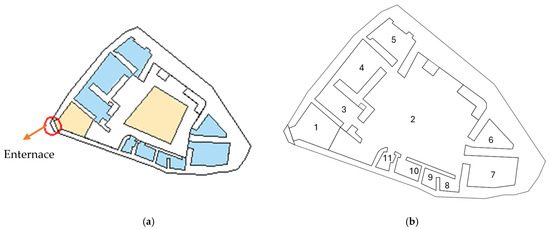

The ICOMOS World Heritage Committee’s decision to include Erbil Citadel on the World Heritage List has brought international attention to its unique and outstanding universal value, confirming its status as a rare and precious cultural site. Hashim Chalbi’s work thoroughly examines the citadel’s urban, compositional, stylistic, and constructive aspects. This work serves as a superb introduction to and an impressive examination of the architectural heritage of Erbil Citadel. A long and venerable history unfolds through this close reading of the citadel [5,6] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Erbil Citadel’s master plan; “Green” the open space of the Citadel, “Brown” the built area, and “Black circle” represents the Hashim Chalbi house. (b) “Red” The Hashim Chalbi house is located within the citadel.

The Hashim Chalbi house embodies the beginning of the end of traditional residential architecture in Erbil, incorporating modern elements that reflect early 20th-century urban life in the city. Located prominently in the heart of the citadel, it is an essential example of the period, with a style that merges traditional insights with modern touches. The building, with its facade of fired bricks and limestone, incorporates stylistic references that may have been inspired by the Western architecture of the period [6,7].

From an architectural standpoint, the Hashim Chalbi house stands out in Erbil, as it fuses aspects of traditional Kurdish architecture. The house is also crucial in an urban setting, underscoring its essential role in the city’s architectural history. This outward-facing interaction with urban space marks a shift from the more enclosed and private character of traditional courtyard houses in urban areas. Inside, the building preserves the details and proportions characteristic of the Empire era [6].

Essential maintenance, including surface treatments, appears to have been delayed. Evaluating a building’s worth encompasses aesthetic, scientific, heritage, and functional elements. Preservation tactics frequently require balancing heritage integrity with adaptive reuse to maintain historical accuracy and ongoing significance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Hashim Chalbi house in Erbil Citadel has a different visual interior view. (a,b) Different angle of the stairway leads to a lower level; (c) traditional carpets displayed on the walls; (d) an entrance or hallway with stairs leading up to a wooden door; (e) a view from outside through a wooden doorway into the building.

The Hashim Chalbi house was constructed from traditional bricks sourced locally, encapsulating historical architectural practices. The materials are durable, aligning with the restoration of Erbil’s heritage. The house’s natural wood doors and decorative finishing styles reflect traditional craftsmanship and cultural authenticity.

The house layout, floor plan, and room dimensions have small but usable rooms. The flow for domestic and communal use is designed to accommodate traditional family living and collaborative ventures, punctuated by a balance of public and private spaces throughout the floor plan.

For the proportions and ratios, the building’s mass focus point is the central courtyard, which provides the correct proportion and orientation to ensure that various units receive optimum ventilation and locality. This arrangement nods to traditional architectural models that favor symmetrical and spatial circulation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Hashim Chalbi house in Erbil Citadel. (a) Exterior views; a view of the house from a side alley; (b) a closer, angled view of the house; (c) a front view of the entrance, featuring a wooden door.

Architectural features: The house’s sturdy walls and solid arches indicate durability and traditional construction. Decorative touches, such as intricate carvings on doors and traditional carpets, allow for exploring culture and narrative within the architecture.

Building orientation: The house lets in natural light and ventilation, creating a comfortable indoor environment suited to the region’s climate. Windows are strategically placed for adequate lighting while maintaining privacy. Meanwhile, a condition and structure assessment show that the house is safe, as demonstrated by the well-maintained walls, sturdy entrance, and wooden elements. This first assessment highlights the house’s preparedness for conservation and adaptive reuse, allowing it to remain a cultural touchstone for the community (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The Hashim Chalbi house. (a) Ground floor plan; (b) upper floor plan.

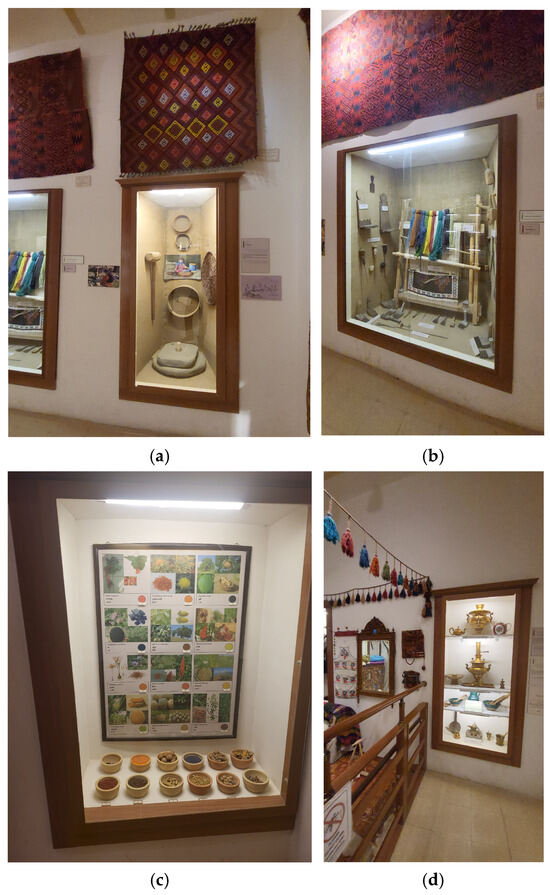

Figure 5.

The Hashim Chalbi house, located in Erbil Citadel, features an exhibit inside the house. (a) Display case showing traditional textile tools; (b) display featuring a conventional loom and weaving tools and demonstrating the textile-making process; (c) display showing a plant with bowls containing natural dyes or seeds; (d) a decorative exhibit of ceramic and metalware items.

4. Methodology

This study’s methodology uses space syntax theory and the DepthmapX 0.8.0 software to examine the spatial configuration of the historical house and its social implications. Developed in the 1960s, space syntax helps understand how spatial configurations affect social interactions, fostering connections within environments. It conveys how visibility within buildings creates movement patterns related to other spatial features. Space syntax analyzes a building’s organization and visual control, enhancing comprehension of spatial interconnections. Combined with the DepthmapX software for VGA and axial map statistics, it allows for evaluating spatial functionality on three levels: configurable, visual, and comprehensive. This approach reveals the impact of design on spatial connections, providing insights into societal choices and opportunities.

The DepthmapX software visualizes topological accessibility and adjacency using isolines, illustrating a building’s spatial layout. It highlights unintended corridors, like blocked staircases. Additionally, DepthmapX enhances our understanding of spatial navigation and interaction, aiding studies on social behavior, functionality, and urban networks. This quantitative analysis connects heritage architectures’ historical layouts with current social needs, guiding adaptive reuse processes.

The methodology of this research combines quantitative spatial syntax analysis using the DepthmapX and AGRAPH v.1.14 software with qualitative architectural interpretation, aligning spatial metrics with cultural and functional principles of museum design.

For this study, the methodology is structured around three core components: [spatial syntax theory, the DepthmapX software, and Justified Graph Analysis (AGRAPH)].

The following is a step-by-step description of the methods applied.

Step 1: Data Preparation

- -

- Analyze the urban spatial layout of the Hashim Chalbi house and construct VGA and axial maps using the UCL DepthmapX software. Import the citadel map into the software in DXF format, then generate an axial map of all lines. The graph illustrates the relationships between each line and the corresponding visibility lines.

- -

- DepthmapX automatically reduces the axial map of all lines to the fewest line map for the entire system, and the analysis is run to calculate the related values of syntactical properties (connectivity and global integration, r = n).

Step 2: Axial and Visual Graph Analysis (DepthmapX)

- -

- An axial map measures whether the house is integrated or segregated in the urban context and the effect of visibility on users’ use of semi-public or public spaces.

- -

- A Visual Graph analysis (VGA) of the house measures syntactical properties (integrations, connectivity, and choice).

Step 3: Justified Graph Analysis (AGRAPH)

- -

- A justified map graph of the ground floor was used to calculate the house’s mean depth and symmetry/asymmetry using the AGRAPH software to address the building’s key control spaces for different visitors.

- -

- Reviewing: Many studies have addressed space syntax theory and this methodology within the historical context. Below are the primary literature links that connect space syntax with heritage studies:

Step 4: Comparative Analysis

- -

- The spatial configurations of the house were analyzed before and after the intervention to check the original layout, comparing the metrics to evaluate changes in terms of accessibility and efficiency.

Many studies utilize space syntax, such as a study of the traditional bazaar in Gaziantep, employing integration and choice studies to evaluate spatial accessibility, and propose conservation strategies that may combine tourism with historicity. Emphasis on the traditional bazaar, a social center integrating busy bazaar streets, was essential for historical trade and social activities, but downtown developments have disrupted this. The study suggests that reintegrating them through pedestrian routes would be satisfactory [7,8]. On the other hand, a study analyzes the spatial configuration of the historic center in the Peninsula of Istanbul. The analysis utilizes Visual Graph analysis and axial map analysis to measure integration spaces in the area, aiming to understand pattern morphology and movement dynamics. The insights of this study revealed the integrated streets in the historical center, which have significant social interaction [8].

Space syntax analyzes an old city’s spatial structure while examining courtyard houses and street patterns. Integration and connectivity are measured to identify limitations and conservation aspects, providing insights into the modern needs of historical buildings. Another study also addresses restoring and enhancing the houses’ accessibility and spatial adjustments [9]. Another study critically evaluated and reinterpreted old Ottoman houses in Turkey. The spatial layout was assessed using a justified graph as a metric for evaluating the regional spatial structure of the houses concerning their conservation strategy. It documented the layout of the houses, particularly Ottoman ones, highlighting characteristics such as socialization around a courtyard to illustrate the social implications within the heritage context [10].

Space syntax theory has been employed, and one study analyzes the configuration of exhibition space in Venice. It uses visual analysis to indicate visitors’ navigation and experiences in heritage space settings. It measures the visibility of the location and observes people’s engagement with a historical site in Venice [11].

Though this study essentially utilizes Visual Graph analysis (VGA) to examine spatial arrangements, the broader methodological contexts within space syntax analysis are also worth mentioning. Axial and segment analyses have been widely applied in studies of historical urban areas to understand pedestrian movement, spatial accessibility, and tourism dynamics. For example, axial analysis was used to analyze tourist flows in the historical core area of Kuala Lumpur [12].

In contrast, segment analysis was used to study tourist spatial behavior in Gulangyu, China, demonstrating how spatial accessibility and connectivity significantly affect tourist distribution [13].

Enhanced connectivity and integration can boost vitality in the Yushan Historic District, suggesting that the space syntax approach has the potential to contribute to the regeneration of historic districts through integrated measures of spatial and functional configurations [14].

Space syntax has been combined with “multi-criteria decision analysis” (MCDA) to simulate pedestrian flow patterns influenced by the street network and urban function attractors in shaping urban spaces. Such observations underscore the importance of combining various space syntax methodologies to enhance our understanding of spatial behavior in heritage environments [15]. Aside from VGA, other space syntax approaches, including axial and segment analyses, have also been used to investigate historical urban spaces. These methods provide different perspectives on spatial organization regarding pedestrian movement, accessibility, and urban form. For example, axial analysis has been conducted to assess historical districts’ spatial integration and connectivity, contributing to developing conservation strategies and urban renewal plans, such as the Sishengci Historic District case study of Chengdu [16].

Particularly in combination with angular and metric distance measures, segment analysis has successfully represented pedestrian flows and access patterns, some of which are fundamental to studying tourism dynamics and the development of walkable spaces. These approaches also have been implemented in planning systems to help support the regeneration of heritage cities and areas by achieving a compromise between preservation and modern urban growth [17].

Space syntax informs adjustments of the Hashim Chalbi house in Erbil Citadel, highlighting the need for integrated spaces, like courtyards, which serve as social areas with strong visual connections. Urban studies underscore the Hashim Chalbi house’s importance within Erbil Citadel as a prime example of conserving historical social functions while addressing current needs.

5. Analysis and Results

As spatial patterns in historical buildings are contextually embedded in cultural and social layers, they demand a multi-layered analysis. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of social behaviors and spatiality would be possible. At the same time, space syntax has been recognized as a quantitative method for studying spatial configurations that extends beyond their descriptive qualities, utilizing computational tools, such as DepthmapX or A graphs, to interrogate aspects like spatial integration and connectivity [18]. The spatial syntax analysis can be classified into two groups based on the site area of change: the urban scale level and the building scale level. This difference enables an understanding of the house within the context of its broader surroundings and articulates the spaces within it. Here is how each scale can be approached in detail.

5.1. Urban Spatial Context Analysis: Visual Graph and Axial Map

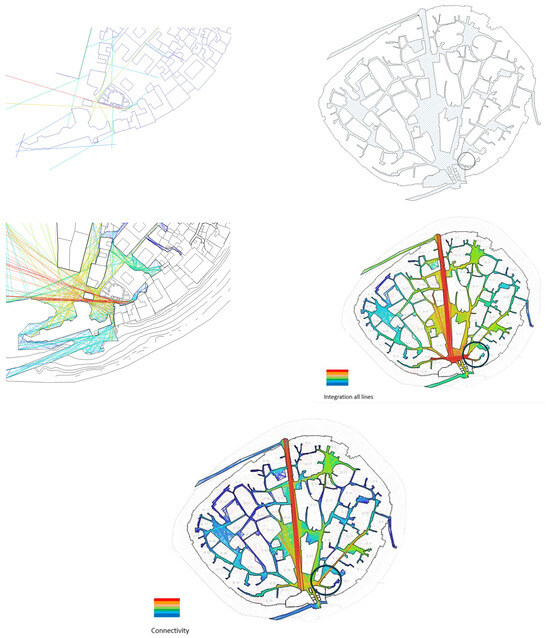

The spatial syntax analysis demonstrates that the chosen historical house is strategically located within an area that exhibits moderate to high integration within the urban fabric. This level of integration supports functional reuse proposals reliant on visibility, access, and public interaction. Statistical metrics further affirm this, showcasing high average integration and a diverse spatial depth typical of adaptable, historically rich urban environments. The main syntactical variables are as follows.

Integration: Global integration means how accessible a space is from every other space in the network. If integration values are high, the system has more connected and accessible space. Local integration concerns the connectivity of spaces within a regional area, analyzing how a space is integrated with its local neighborhood.

Connectivity is the number of direct connections of a given space (node) to adjacent spaces. This variable enables us to identify well-connected areas in the layout.

Depth: This denotes the number of direct connections (edges) a space has to other spaces, indicating its position within the spatial network. Visual Depth: This refers to how spaces in a space are based on their sequencing and what is visually exposed vs. what is visually hidden in a space from the viewpoint of points.

The axial line is where the lines represent the longest and shortest set of lines covering the entire spatial system. The colored lines (red, yellow, green, and blue) indicate varying levels of visual and spatial integration, ranging from high (red) to low (blue). The central building (presumably the focus for reuse) appears connected to multiple intersecting axial lines, suggesting it sits at a moderately connected junction within the urban network. This map shows the spatial network’s global integration values (HH). Red lines denote highly integrated spaces that are more accessible and central to pedestrian movement. Blue lines indicate the most segregated or least connected paths. The clustering of red and yellow lines near the target house suggests it lies within a spatially integrated and well-used path, which is critical for use. Statistical summary (integration HH values): The average integration value is 1.71. This is relatively moderate to high, indicating that spaces in this network are decently accessible on average.

- -

- The minimum is 0.65, and the maximum is 3.67: this wide variation confirms a heterogeneous spatial network typical of historic urban areas.

- -

- The standard deviation is 0.63: this indicates significant variability in integration levels, and the count suggests that the sample includes 26 axial segments, possibly within a defined local sector.

The spatial data indicates that the building is well-integrated within its network, rendering it suitable for public or semi-public use. Nearby high-integration zones enhance visitor-oriented functions. The varying integration values in the surrounding network may present zoning opportunities, such as positioning quieter or private functions along more secluded edges and placing active or public functions toward integrated fronts (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

VGA and axial analysis for Erbil Citadel regarding the Hashim Chalbi house.

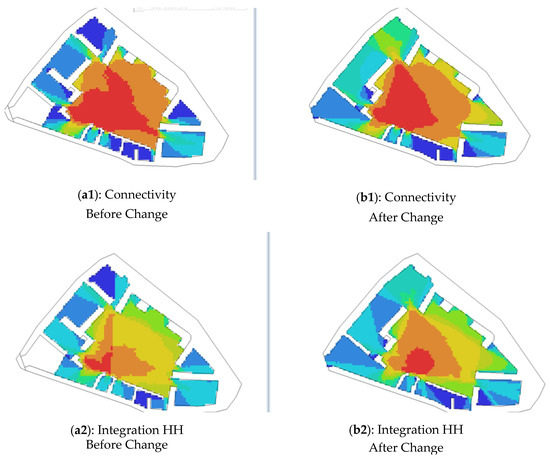

5.2. Building Spatial Analysis

The following properties were measured for the house before and after changes were made to the interior walls. These outputs present two visual integration analyses, each depicting different types and levels of visual interconnectivity within the spatial layout.

5.2.1. Visual Analysis (VGA): Integration

The integration visual values are as follows: minimum: 3.82, maximum: 25.5, and mean: 13.5. The colors in space convey areas of visual integration (lighter centers, such as yellow and red), suggesting that this is a location where one can be seen or attract attention. The second plan has a broader span, with values ranging from 5.23 to 26.2 and an average of 15.5. Similar to the pre-change plan, higher-level visual integration regions cluster at the center; however, higher overall integration is reflected in the elevated mean value (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Visual integration (HH) comparison data.

The VGA integration example indicates a denser integration in fewer locations (i.e., it has fewer values and a marginally lower average). This might mean visual barriers or a less intuitive arrangement disrupts the visual connection. Visual integration is better overall, confirming a more significant number and a broader spread of values for the right plan. This suggests that they are more visible and accessible due to a more spatially configured arrangement, whether in a single row or arranged closer together with stable relations with one another or alternative ideas with fewer obstructions.

5.2.2. Visual Analysis (VGA): Connectivity

In the pre-change plan, the connectivity values range from a minimum of 34 to a maximum of 173, with an average of 982. The image indicates that areas with high connectivity (notably warm colors, like red and orange) are mainly concentrated in the central region, suggesting that this area is well-connected and accessible (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Connectivity comparison data.

5.2.3. Justified Map

The justified map was used to perform a spatial analysis to help better understand the heritage house’s spatial arrangement and connection to the larger neighborhood.

The spatial arrangement of the house’s design encourages functional zoning, where private quarters are screened from public spaces, and communal areas, such as the courtyard, are designed for family and community activities. Functional relationships show how traditional households balance public hospitality and private family life. The spatial distribution facilitates social rituals, communal events, and daily living.

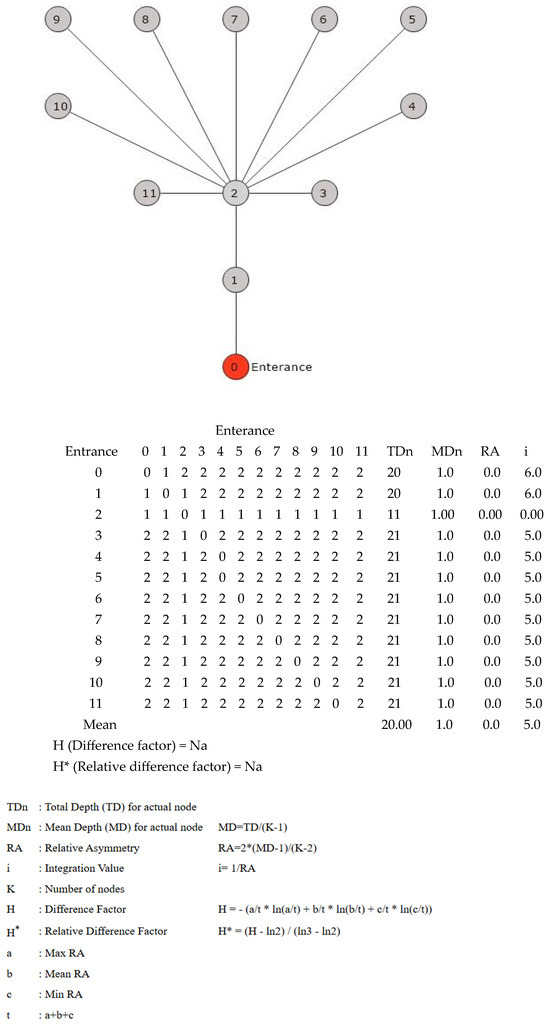

Justified graphics represent a spatial system for which hierarchy is a measure. Hierarchy is used within space syntax analysis to illustrate how the physical arrangement of the spaces in a floor plan is structured regarding their connectivity and accessibility from any given starting point (a spatial network root node). It translates the spatial arrangement into a diagram where the spaces are arranged in depth (i.e., the distance in the number of links or steps needed while starting from the ‘root’). Justified maps can help architects and planners understand how spaces are structured; how open or closed they might be; and how much they impact movement, interaction, or social experience. They were developed in The Social Logic of Space (1984) by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson as part of space syntax theory (see Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Visual graph—connectivity and integration analyses before and after changes.

Figure 8.

The Hashim Chalbi house (a) ‘Blue areas’ represent private or semi-private rooms; ‘Beige areas’ indicate public or shared spaces; Red Circle’: Highlights the main entrance. (b) The spaces numbered 1 to 11 correspond to individual rooms.

The Main Significant aspects of the graph

- -

- “Entrance” (Node 0) is red. Nodes (spaces) are numbered 1 to 11 to indicate their connectivity and depth from the entrance.

- -

- The floor plan of the building and the numbering of the control points, corresponding to the nodes of the graph (0), are for the entrance, and Nodes 1 to 11 are for inner spaces.

- -

- This graph is tree-shaped, and there is only one path from the entrance: entrance (0) → Node 1 → Node 2 → Nodes 3 to 11.

- -

- Node 2 is a central node with direct access to nine more nodes (3 through 11), so it identifies that it has access to most of this building.

- -

- Beyond this, all positions are equidistant, and Node 2 is at the same depth (3), creating a topology of no branches. Node 2 is interconnected by some other space at the bottom of the similarly “rooted” set.

The spatial configuration analysis of the graph

- -

- The “Depth” from the entrance, in the graph, representsDepth 1 = (one step).Depth 2 = (two steps), where Node 2 is linked to Node 1.Depth 3 = (three steps), or those spaces connected to Node 2.

- -

- The entrance represents the base of the graph (Node 1), while the foyer, the transitional space of the house (Node 2), is directly linked to the entrance. The courtyard (Node 2), the central area, connects to Node 2 and other spaces in the floor plan from Node 3 to Node 11, representing the house’s bedrooms and storage areas before being converted into a museum.

- -

- The spaces are arranged around the courtyard as a central hub, with a linear path from Node 1 to Node 2 and no alternative entrances. Meanwhile, Nodes 3 to 11 represent symmetry and isolation, arranged linearly in Node 2 at a depth of three steps.

- -

- All movements within the pattern must go through the hub area (Node 2), while privacy, represented by Nodes 3–11, is two steps from the entrance, making it suitable for private functions.

- -

- At the same time, Node 2 incorporates social interaction, serving as the primary space for social integration and the most crowded area in the house designed for communal use.

- -

- Node 2 serves as the most organized environment and the leading center for movement and interaction.

- -

- Nodes 3–11 are more profound and appropriate for unique or isolated functions (see Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 9. Justified graph for the Hashim Chlabi House using AGRAPH software.

Figure 9. Justified graph for the Hashim Chlabi House using AGRAPH software.

6. Discussion

Connecting the spatial syntax results of the Hashim Chalbi house with key criteria for museums allows us to categorize the findings accordingly. This connection illustrates how the house’s arrangement influences its role as a heritage museum. This study investigates the importance of visitor engagement in museums and the intersection of experiential learning and visitor interactions. The Hashim Chalbi house is an example of the citadel’s architectural style. It features a courtyard, an entrance vestibule, thick mudbrick brace walls, and adjacent rooms for family living and storage.

The justified graph of the house features a central design layout, with the entrance (Node 0) connecting to the linear walkway (Nodes 1 and 2) and fanning out into nine peripheral regions (Nodes 3–11). Node 2 has an MDn of 1.00, which is higher than expected, indicating that Nodes 3–11 (at Depth 3, with an MDn of 1.91 and i of 5.49) are generally less accessible, implying they serve private or specialized purposes. The floor plan and elevational design reflect this, with the building comprising a central courtyard as Node 2, wrapped by a sequence of small rooms, embodying controlled circulation in a traditional design layout.

In contrast, the connectivity and visual integration (VH) maps of the Hashim Chalbi house offer a more exhaustive urban analysis. The connectivity map shows values ranging from 158 to a maximum of 267, with high nodal connectivity represented in vivid colors. The red and orange areas indicate locations with many direct interactions, such as courtyards. Moreover, the visual integration map (HH R3) presents an average integration of 13.5 and a peak of 23.5, where red and dark red zones signify greater visual accessibility and integration, likely reflecting central public or semi-public spaces. There are 616 nodes with a high degree (e.g., >156) and 70 integrated nodes (>215), pointing to less integrated regions.

Comparing the structures, some commonalities are observed, while others differ. The highly integrated Node 2 for the simulated house corresponds to the Hashim Chalbi house’s courtyard as a well-connected (26.7) and integrated (23.5) central area. In both designs, the straight passageway imbues the project with the privacy and security (notions culturally intrinsic to Erbil Citadel and its history of vulnerability) of the linear act of entering, from the vestibule to the courtyard. The Depth 3 (positioning) nodes of 3–11 in the hypothetical house correspond with the peripheral spaces of the Hashim Chalbi house, which exhibit poor integration (in this case, the blue zones; V1560.40); these peripheral compartments are likely to be private and storage spaces.

The moderate integration value of the Hashim Chalbi house (13.5) indicates that most local areas are easily accessible, which is crucial for enhancing the visitors’ museum experience through improved mobility and opportunities for exploration. Conversely, the maximum integration value (23.2) suggests the existence of central, well-connected spaces that function as social and educational hubs within the building.

The standard deviation of the integration value (5.59) indicates the coverage of the used spaces, and the areas with low integration may restrict movement. Applying a visual connectivity analysis, such as sightlines and the placement of exhibits in visually integrated spaces, can help address these disparities and enhance visitors’ attention to and engagement with the content [19].

Studies on experiential learning in museums emphasize the importance of immersive environments in fostering a sense of suspended disbelief and engagement with exhibits [20]. In doing so, the house can leverage its spatial strengths by creating an environment that facilitates the attainment of educational goals through its well-integrated spaces, thereby fostering a closer bond with visitors and amplifying the experience of the heritage narrative. This method uses adaptive reuse theory to transform historic structures while preserving their architectural value and enabling modern use [21].

The minimum integration value (3.6) and a distribution of 2.64 spaces in the building enable functional zoning, a crucial requirement for the museum. More distant zones can accommodate specific uses, such as storage or staff offices, while keeping the walkway of all public areas reserved for exhibitions and visitor services.

This approach contributes to broader debates about heritage sustainability by exploring how adaptive reuse can reintegrate local narratives into museum functions, foster empathetic relationships with the surrounding context, and allow the site to evolve while ensuring the sustainability of intangible cultural heritage values.

With high integration values, the Hashim Chalbi house is an ideal case for transformation into a museum. The aim is to balance the conservation of a historic building while ensuring public access, thereby contributing to broader debates about how historic buildings can maintain social relevance in contemporary contexts [22]. This zoning strategy preserves the sanctity of collections while adhering to universal accessibility and inclusive design principles outlined in museum design, accommodating a diverse range of audiences, including those with varying abilities [23]. Improved signage, walkways, and guided paths through low-integrated areas will help reduce bottlenecks and enhance wayfinding and visitor flow. The spatial configurations and impacts of movement are as essential as the historic fabric, which can be adapted to meet universal design guidelines [24]. Installation-based exhibits encourage visitors to explore the museum’s rooms, aligning with museum design theories emphasizing flexible configurations’ educational and social benefits [25].

More innovatively, multimedia displays in back-of-house spaces could help mitigate some of their remoteness, creating the experiential continuity that visitors desire. By repurposing these spaces to provide visitors with information about the house’s social significance, the museum can foster a conversation between the past and the present, in line with heritage management strategies prioritizing community investment and cultural continuity [26]. This study contributes to the discourse on the conservation and museumification of historic buildings for cultural purposes by applying spatial syntax analysis to the Hashim Chalbi house.

By demonstrating how spatial strengths can be leveraged for contemporary use, it engages with adaptive reuse, promotes accessibility, participates in universal design, and incorporates local narratives into the museum experience, thus contributing to heritage sustainability. These findings provide a model for other heritage sites that carefully balance the tensions between preservation and transformation, demonstrating that historic buildings can be active contributors to contemporary society’s processes [27] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Justified Graph map vs. Visual Graph analysis.

7. Conclusions

As a historical house, the Chalbi house serves as a model for understanding the processes of spatial constitution and the hierarchical organization of its components and furnishings, reflecting the upper-class manners and ideas of the house’s owner. Since buildings are the most immediate reflection of their residents’ cultural life, a deeper understanding of the spatial structure of traditional historic settlements is crucial for comprehensively understanding architectural alterations resulting from the impact of socio-spatial fluctuations within living environments.

The Justified Graph Map Analysis of the house indicates a center-focused layout centered around a courtyard, which serves as its primary social area, parallel to the house typology found in Erbil Citadel. However, this unidirectional layout offers limited accessibility compared to the citadel’s more interconnected systems. In contrast, the Visual Graph analysis of the Hashim Chalbi house illustrates a deeper and more spread spatial network, providing enhanced connectivity that embodies the historical urban nature of the citadel, where courtyards and streets promote social engagement. With its well-connected nodes, this adaptable house is a museum that enhances movement in the proposed house while preserving cultural ties to citadel architecture. This underscores the value of space syntax in heritage conservation; it can be adapted as a historical house residence, and by integrating the node-connected connectivity of the Hashim Chalbi house, one can maintain its functionality and cultural significance within Erbil Citadel.

This research enhances the architectural literature on Erbil Citadel and encourages interdisciplinary discussions on how space influences socio-cultural experiences. It adds to the study of social science in architecture. Additionally, the data supports the need for less integrated zones for storage or staff, making universal design essential for accessibility. These spatial characteristics, qualitative indicators, historical context, and cultural identity represent the social and spatial relationships in Erbil Citadel’s neighborhoods. This adaptation project enhances the architectural literature on Erbil Citadel and fosters interdisciplinary discourse on spatial design and socio-cultural experience. The depth map analysis emphasizes the house’s usability and provides a replicable method for assessing built heritage, guiding restoration or redevelopment, preserving historical integrity, and incorporating contemporary functionality. Ultimately, the Hashim Chalbi house exemplifies architecture’s role in reflecting and shaping society, contributing to broader studies at the intersection of social science, museum-making, and heritage practice. This research opens avenues for exploring how such spaces can serve as sustainable cultural institutions that adapt to contemporary needs.

This research significantly differs from similar works by transcending the boundaries between architectural analysis, heritage preservation, museum studies, and social science. The investigation of these historical spatial configurations and their contemporary adaptive reuse is illustrated using a depth map analysis, reflecting how technical spatial analysis can delegate cultural preservation decision-making.

It also offers objective criteria for assessing spatial relationships in historical buildings of cultural interest. The results provide scientific guidance for practitioners to conserve the historic buildings in Erbil Citadel. By externalizing space syntax, the analysis reveals the parts of the building that are most important to maintain for preserving its cultural and social value.

This analysis of the Hashim Chalbi house demonstrates how historical spatial configurations reflect historical social structures, and how social evolution has accommodated new public use forms. It also illustrates that analytics can be used for heritage research and serves as educational material for students and researchers in heritage studies. This research can be considered a capacity-building effort for heritage conservation by broadening access to such methodologies.

Collaboration with contemporary practitioners is recommended, especially if heritage is to survive as a meaningful source of spatial configuration. The findings advise conservation strategies that conserve past spatial practices throughout the future of the Hashim Chalbi house and other houses in the citadel.

The limitations of this research are notable, including the absence of physical evidence on how actual visitors are accustomed to moving and perceiving the spaces inside the Hashim Chalbi house. Including visitor-tracking surveys, interviews, or observational studies would validate the theoretical predictions from the space syntax analysis and would provide a more detailed explanation for modern spatial use. Such empirical validation would enhance the generalizability of the findings to museum design and visitor experience planning. While the lack of expert review limits the findings, it allows further enrichment. Future research should include a multidisciplinary panel to evaluate the findings against best practices in heritage management and museum design. By questioning its methodological significance, this process aims to make this study’s adaptive reuse aspirations more relevant, demonstrating how type can serve place and fostering governance among partners with shared spatial goals.

Although the functionality of the DepthmapX software is robust, there are fundamental constraints regarding 3D relationships in space and time. It is important to note that this analysis heavily focuses on 2D relations in space. Additional research should explore alternative analytical approaches to address these dimensional and temporal issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.S.G. and E.S.Z.; methodology, W.A.S.G.; software, W.A.S.G.; validation, E.S.Z. and T.M., formal analysis, W.A.S.G.; investigation, W.A.S.G. and E.S.Z.; resources, E.S.Z., W.A.S.G., and T.M.; data curation, W.A.S.G. and T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.S.G.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and E.S.Z.; visualization, W.A.S.G.; supervision, E.S.Z. and T.M.; project administration, E.S.Z. and T.M.; funding acquisition, University of Pecs. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. This publication falls within the ‘Call for Grant for Publication’ framework of the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary.

Data Availability Statement

The data in the text is reliable and presented in the form of tables and graphs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mariottini, C. The City of Arbela. Claude Mariottini–Professor of Old Testament. 2014. Available online: https://claudemariottini.com/2014/08/13/the-city-of-arbela/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Arbela (Assyrian Arbailu). Encyclopaedia Iranica. Available online: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arbela-assyrian-arbailu-old (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Vrdoljak, A.F. Unravelling the cradle of civilization ‘layer by layer’: Iraq, its peoples and cultural heritage. In Cultural Heritage, Diversity and Human Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hashimi, F.W.S. The hidden face of Erbil: Change and persistence in the urban core. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2016. Available online: https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/31613/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Seismic Action. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2015, 153, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaqoobi, D.; Plichelmore, D.; Tawfiq, R.K. Highlight of Erbil Citadel: History & Architecture; Kurdistan Region Government Governorate of Erbil High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization. 2016. Available online: http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Yapici, F.; Vurdu, H. General Characteristics of Historical Safranbolu Houses Listed in the UNESCO World Heritage Cities. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2019, 27, 622–630. Available online: https://www.idosi.org/mejsr/mejsr27(8)19/10.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Kubat, A.; Özer, Ö.; Ekinoglu, H. The Effect of Built Space on Wayfinding in Urban Environments: A Study of the Historical Peninsula in Istanbul. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium; Greene, M., Reyes, J., Castro, A., Eds.; PUC: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2012. Paper Ref #8029. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338778900_the_effect_of_built_space_on_wayfinding_in_urban_environmENTS_a_study_of_the_historical_peninsula_in_Istanbul#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Malhis, S.; Al-Nammari, F. Interaction Between Internal Structure and Adaptive Use of Traditional Buildings: Analyzing the Heritage Museum of Abu-Jaber, Jordan. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2015, 9, 42–56. Available online: https://www.archnet.org/publications/10282 (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dursun, P. Space Syntax in Architectural Design. In Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, June 2007; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228646158_Space_Syntax_in_Architectural_Design#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Psarra, S.; Grajewski, T. Describing Shape and Shaping Description. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–11 January 2001; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238683190_Describing_Shape_and_Shape_Complexity_Using_Local_Properties#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Mansouri, M.; Ujang, N. Space syntax analysis of tourists’ movement patterns in the historical district of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J. Urbanism Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 10, 163–180. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17549175.2016.1213309 (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Ye, Y.; Xu, W.; Law, A. Understanding tourist space at a historic site through space syntax analysis: The case of Gulangyu, China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Malek, M.I.A.; Ja`Afar, N.H.; Sima, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Z. Unveiling the potential of space syntax approach for revitalizing historic urban areas: A case study of Yushan Historic District, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. Street network or functional attractors? Capturing pedestrian movement patterns and urban form with the integration of space syntax and MCDA. Urban Design Int. 2022, 26, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ahmad, Y.; Mohidin, H.H.B. Spatial Form and Conservation Strategy of Sishengci Historic District in Chengdu, China. Heritage 2023, 6, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-M.; Tang, Y.-F.; Zeng, Y.-K.; Feng, L.-Y.; Wu, Z.-G. Sustainable Historic Districts: Vitality Analysis and Optimization Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2025, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz Yıldırım, E.; Çağdaş, G. Space Syntax Analysis of Traditional Architectural Pattern of Gaziantep in the Context of Socio-culture. Gaziantep Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 17, 508–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, O.K.; Ismail, S.; Franco, D.J. Urban and Tourism Development Projects for Cities Citadels (Aleppo and Erbil). 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/93309408/Urban_and_tourism_development_projects_for_Cities_Citadels_Aleppo_and_Erbil_ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Elaraby, M. Architecture and Urban Transformation of Historical Markets: Cases from the Middle East and North Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359200187 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Assassi, A.; Zidani, H.; Mebarki, A.; Sekhri, A.; Hamouda, A. Recognizing the inner environment organization within buildings of ancient civilizations using a quantitative approach. Sci. Cult. 2022, 8, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H. Assessing the impact of exhibit arrangement on visitor behavior and learning. Curator 1993, 36, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country—Revisited, Illustrated Reprint ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; 676p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Leask, A. Visitor engagement at museums: Generation Y and ‘Lates’ events at the National Museum of Scotland. Museum Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamraie, A. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability, 3rd ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017; 336p, Available online: https://www.upress.umn.edu/9781517901646/building-access/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Sluis Thiescheffer, W.; Bekker, T.; Eggen, B.; Vermeeren, A.; De Ridder, H. Measuring and comparing novelty for design solutions generated by young children through different design methods. Design Stud. 2016, 43, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzera, E. The Socio-Economic Impact of Cultural Heritage: Setting the Scene. In The Socio-Economic Impact of Cultural Heritage; Panzera, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).