Comprehensive Review of Ecosystem Services of Community Gardens in English- and Chinese-Language Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Resources

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Result

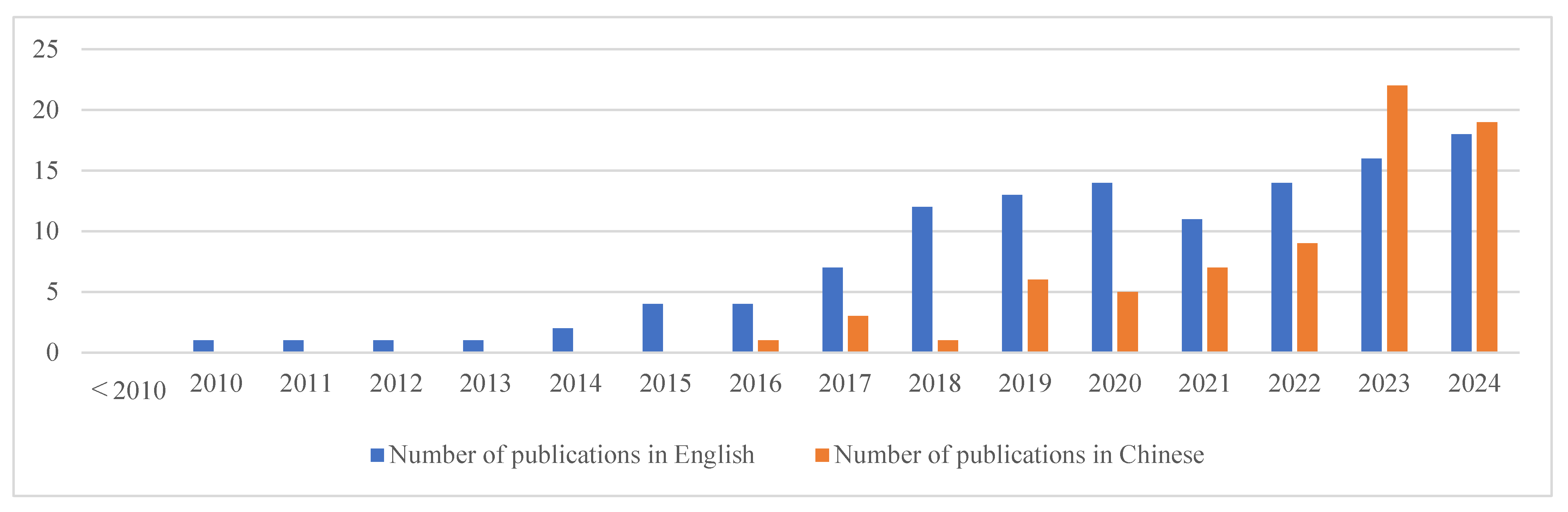

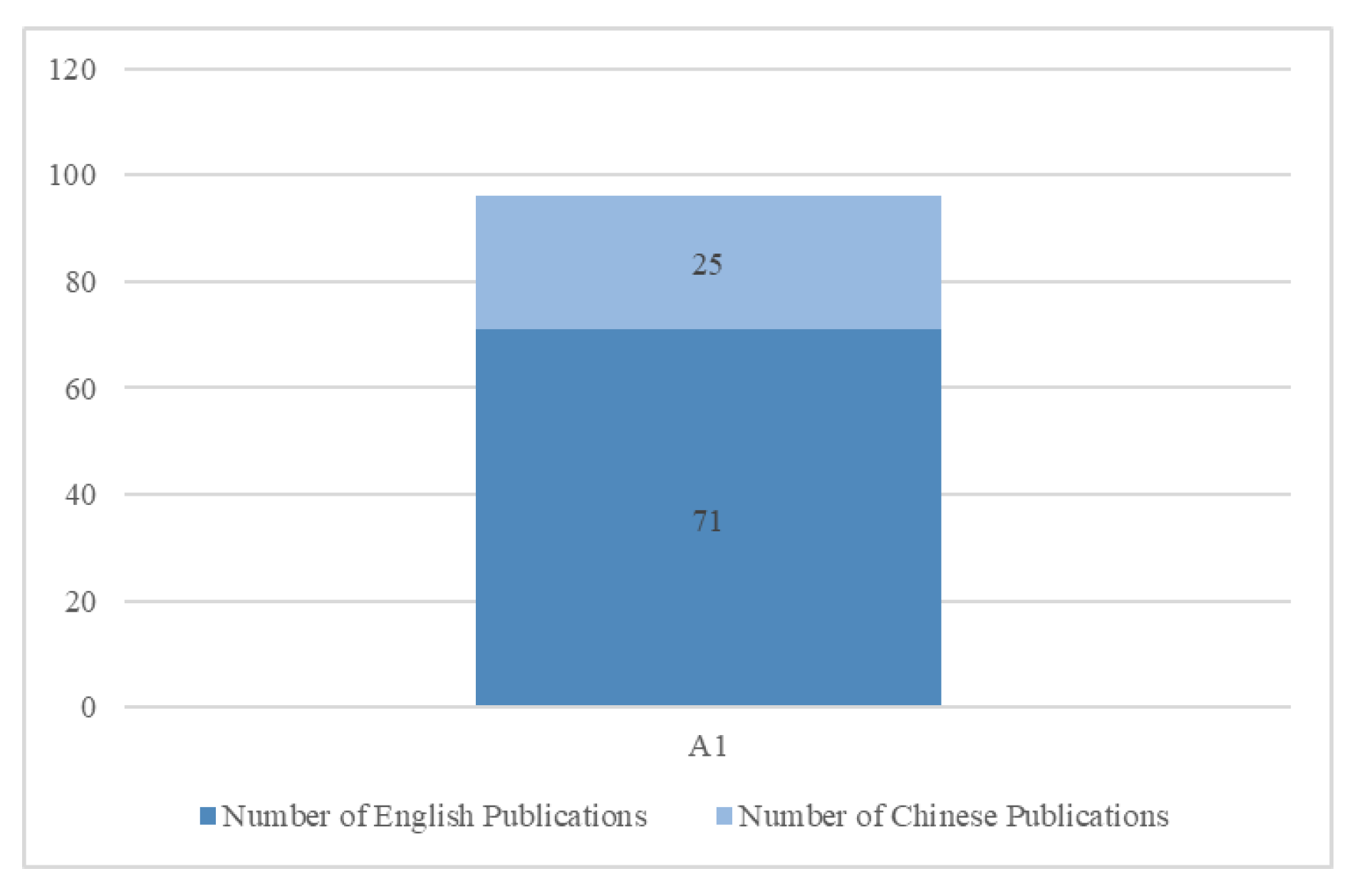

3.1. Publication Years and Numbers

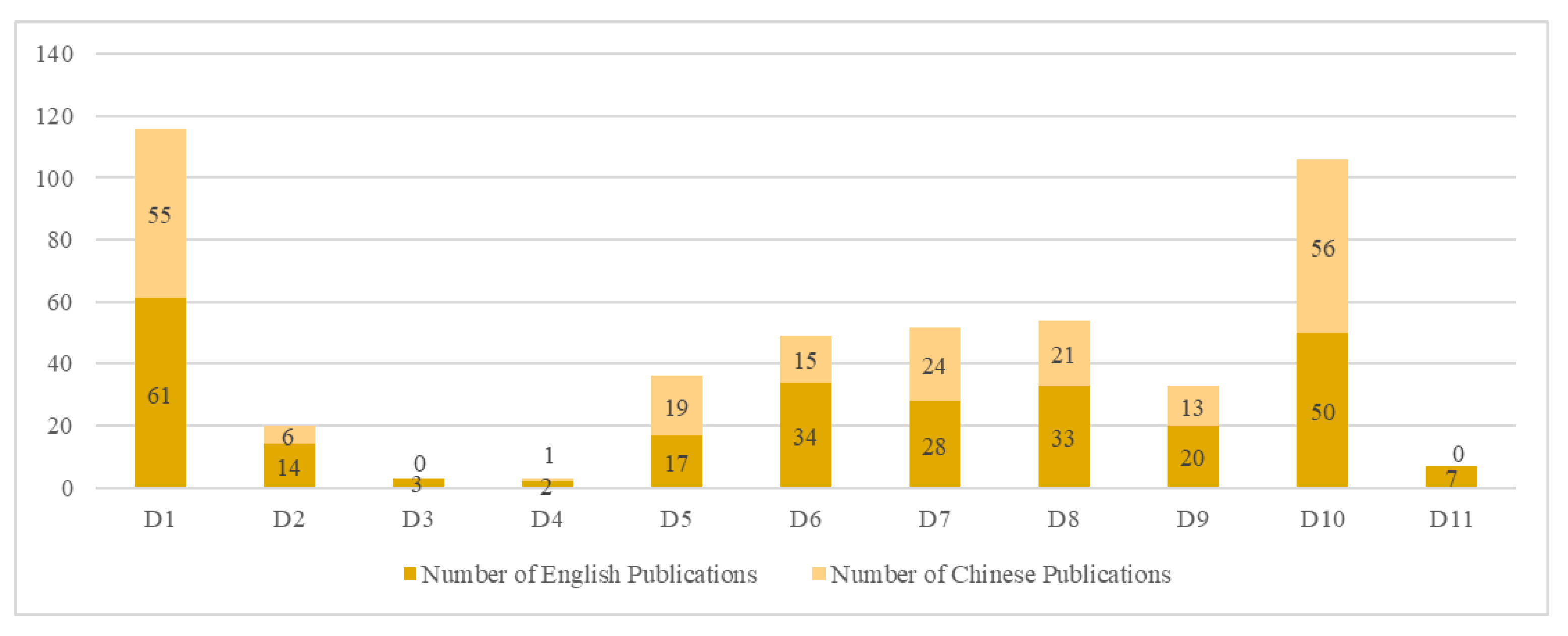

3.2. Study Locations

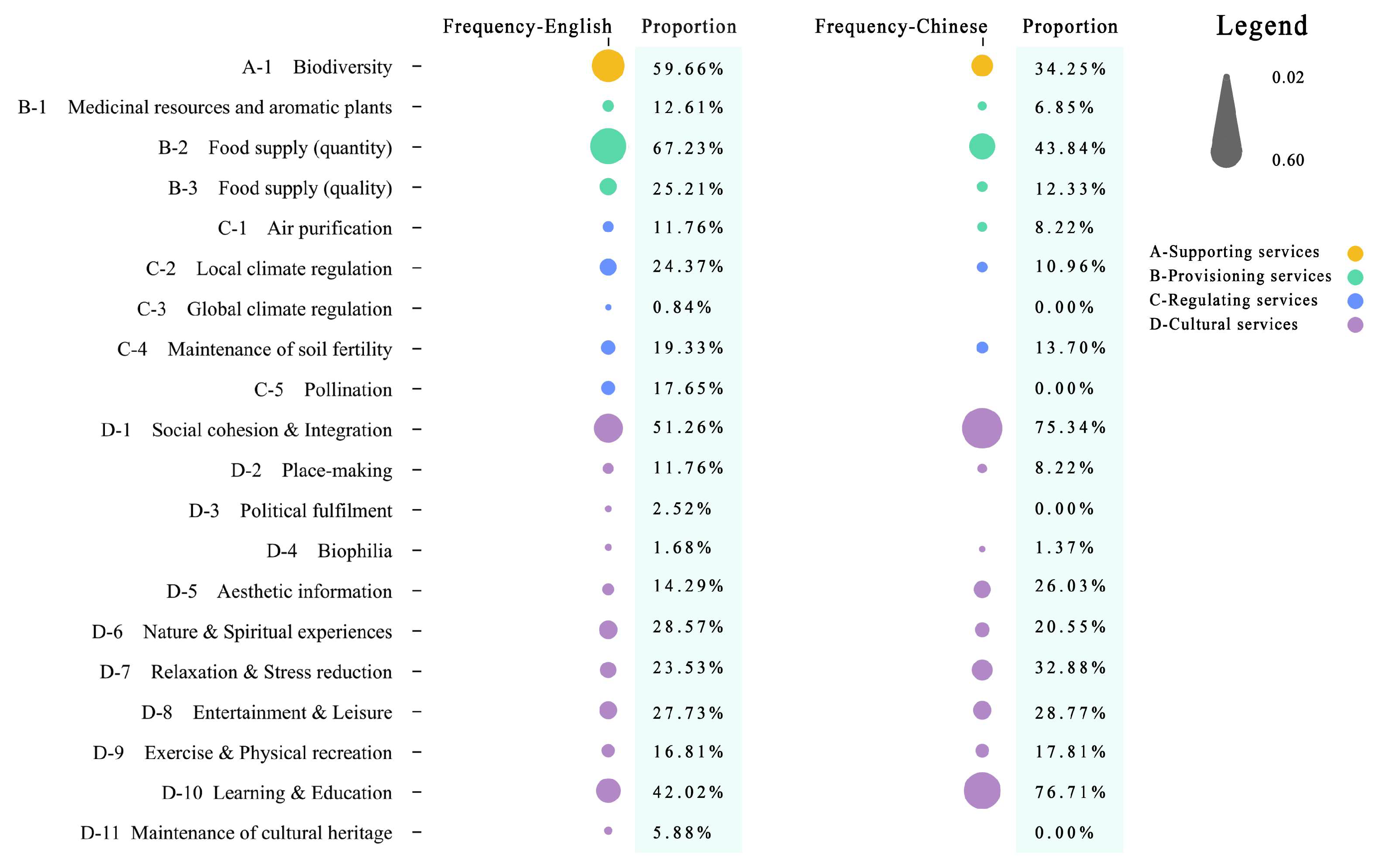

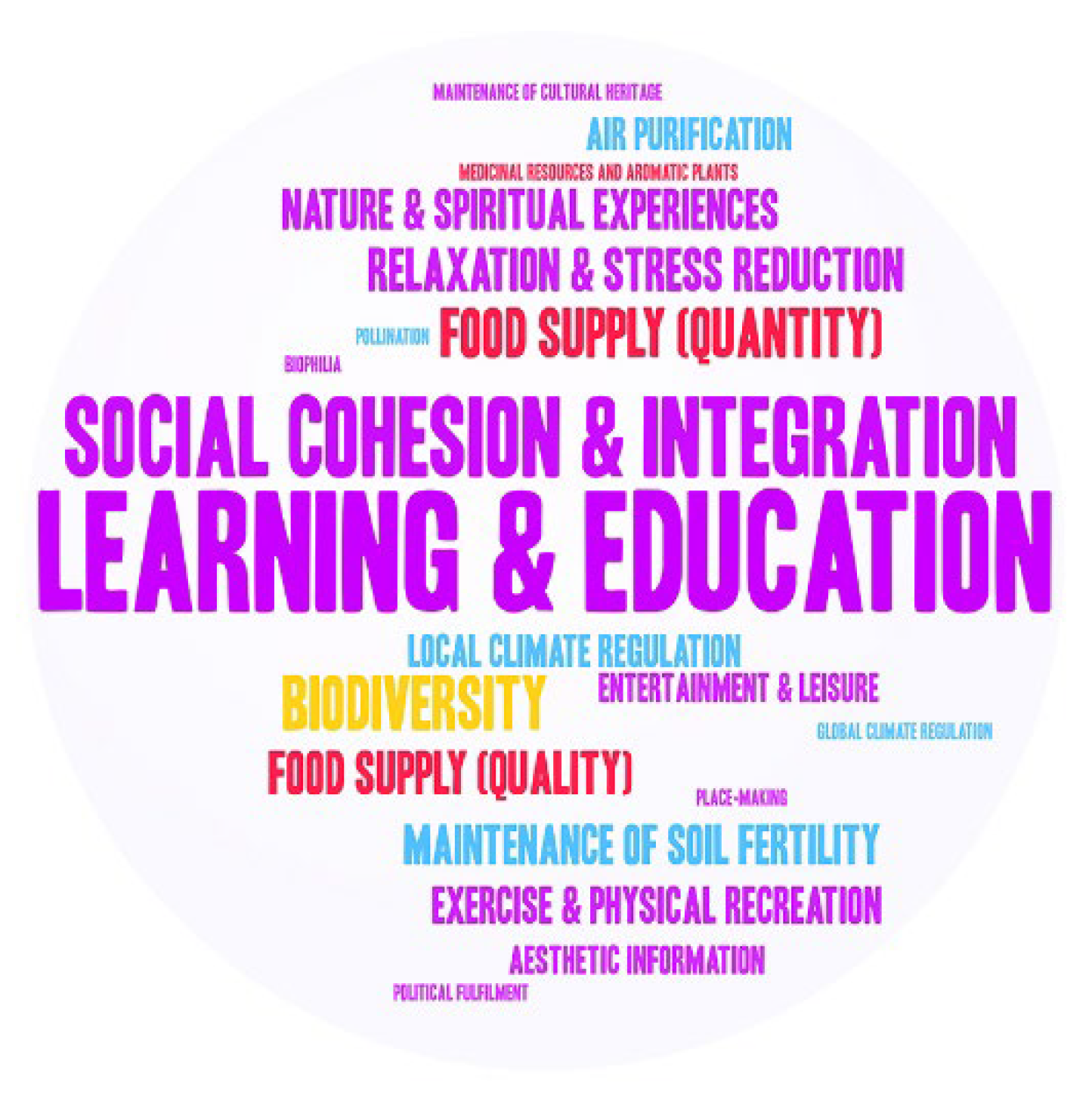

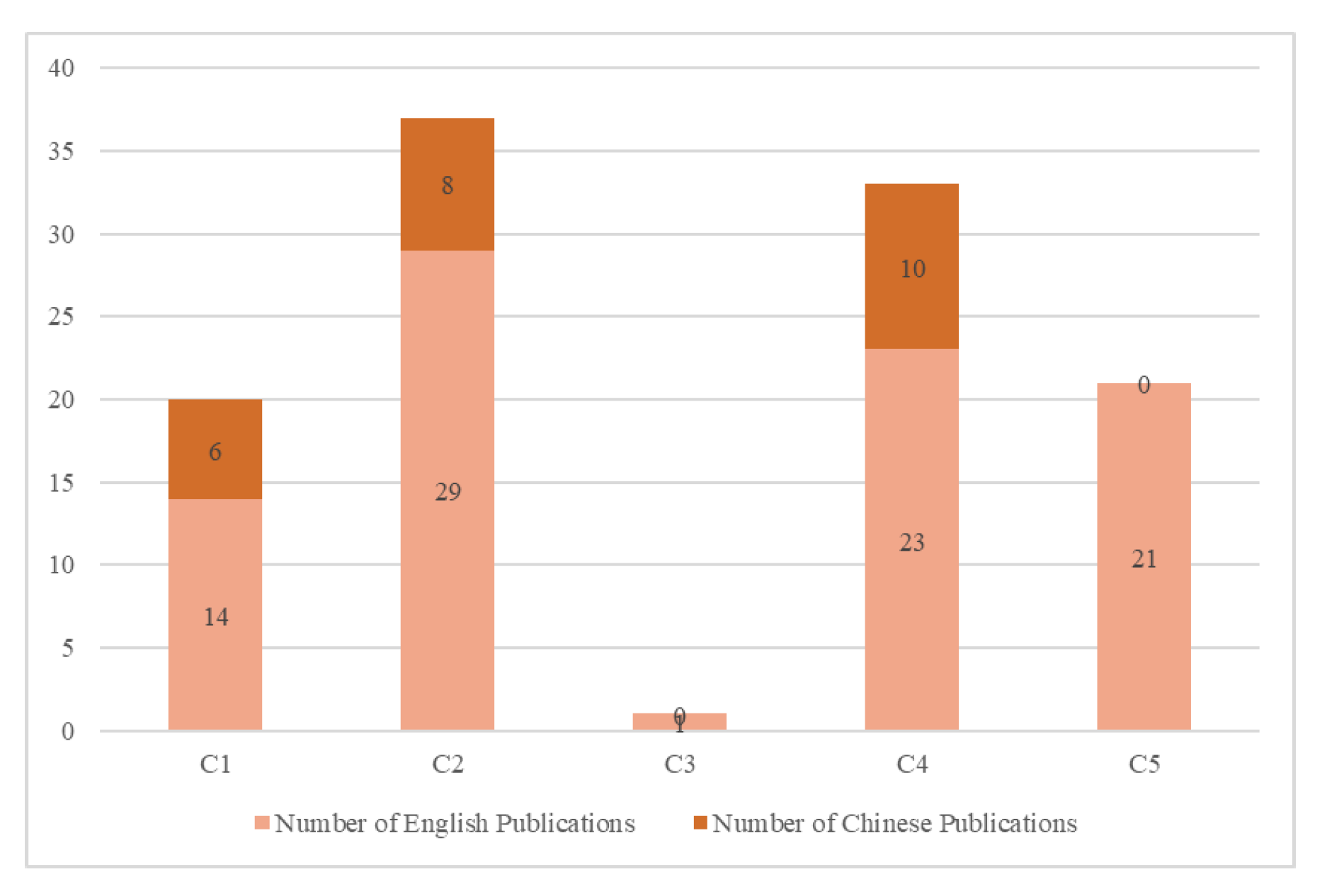

3.3. Research Topics

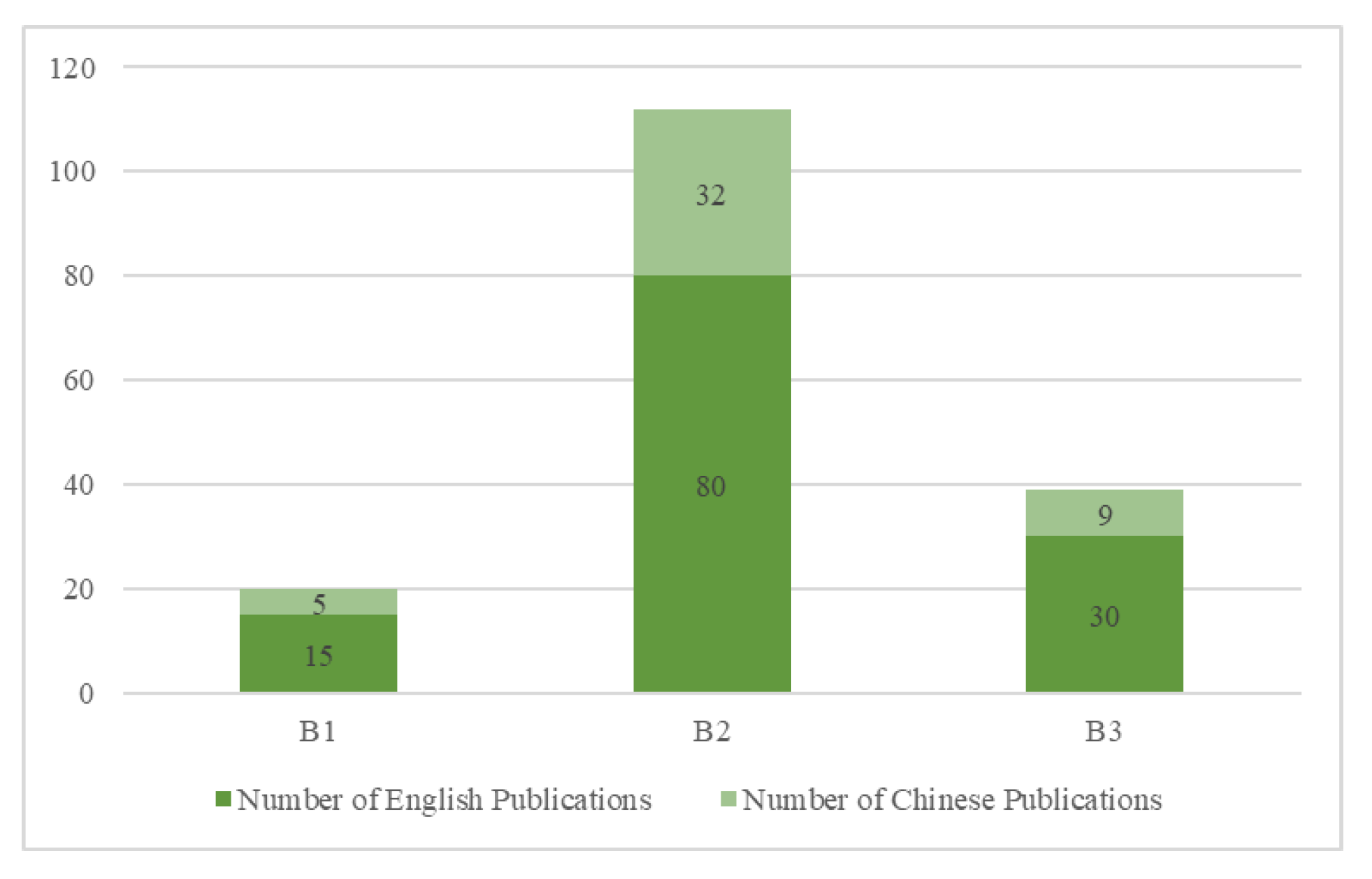

3.3.1. Provisioning Services

3.3.2. Supporting Services

3.3.3. Regulating Services

3.3.4. Cultural Services

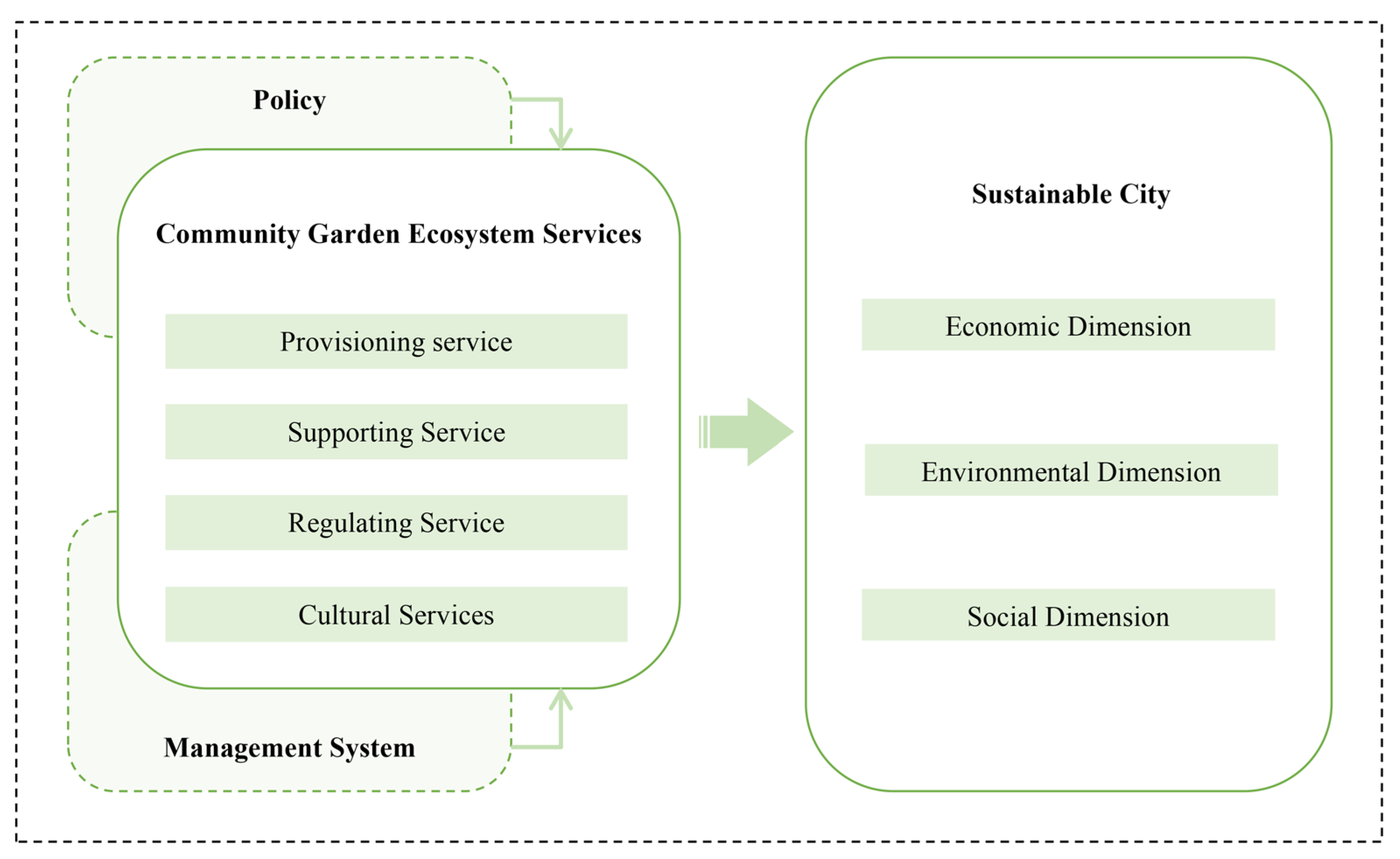

4. Discussion

4.1. The Publication Timeline and Quantity Are Related to Governance Frameworks for Community Gardens

4.2. Study Locations Are Influenced by the Local Management System and Climatic Conditions

4.3. Research Topics Respond to the Need for Urban Sustainable Development and Human Well-Being

4.4. Adaptive Planning Strategies for Community Gardens Under Different Ecosystem Service Orientations

4.5. Knowledge Gaps and Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lam, D. The Next 2 Billion: Can the World Support 10 Billion People? Popul. Amp Dev. Rev. 2025, 51, 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Liu, Z.; Yu, W.; Chen, W.; Jin, D.; Sun, S.; Dai, R. Trend of Urbanization Rate in China Various Regions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 772, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hatab, A.; Cavinato, M.E.R.; Lindemer, A.; Lagerkvist, C.-J. Urban Sprawl, Food Security and Agricultural Systems in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cities 2019, 94, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatti, W.; Majeed, M.T. Information Communication Technology (ICT), Smart Urbanization, and Environmental Quality: Evidence from a Panel of Developing and Developed Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cheng, D.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Feng, Z. Spatial-Temporal Change of Ecosystem Health across China: Urbanization Impact Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. New Urban Models for More Sustainable, Liveable and Healthier Cities Post Covid19; Reducing Air Pollution, Noise and Heat Island Effects and Increasing Green Space and Physical Activity. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklina, V.; Sizov, O.; Fedorov, R. Green Spaces as an Indicator of Urban Sustainability in the Arctic Cities: Case of Nadym. Polar Sci. 2021, 29, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “We Don’t Only Grow Vegetables, We Grow Values”: Neighborhood Benefits. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315259819-7/grow-vegetables-grow-values-neighborhood-benefits-community-gardens-flint-michigan-katherine-alaimo-thomas-reischl-pete-hutchison-ashley-atkinson (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Egli, V.; Oliver, M.; Tautolo, E.-S. The Development of a Model of Community Garden Benefits to Wellbeing. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I. Categorizing Urban Commons: Community Gardens in the Rhine-Ruhr Agglomeration, Germany. Int. J. Commons 2018, 12, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.K.; Trinidad, N.; Bickford, S.H.; Bickford, N.; Torquati, J.; Mushi, M. Engaging Residents in Planning a Community Garden: A Strategy for Enhancing Participation Through Relevant Messaging. Collab. A J. Community-Based Res. Pract. 2019, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, L.; Barnett, K. The Significance and Praxis of Community-based Sustainability Projects: Community Gardens in Western Australia. Local Environ. 1998, 3, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, J.; Norman, C.; Sempik, J. People, Land and Sustainability: Community Gardens and the Social Dimension of Sustainable Development. Soc. Policy Adm. 2001, 35, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.; Freedman, D. Review and Analysis of the Benefits, Purposes, and Motivations Associated with Community Gardening in the United States. J. Community Pract. 2010, 18, 458–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, D.; Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. Past Results and Future Directions in Urban Community Gardens Research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshyar, E. Residential Rooftop Urban Agriculture: Architectural Design Recommendations. Sustain. ITY 2024, 16, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M. Green Infrastructure as Key Tool for Climate Adaptation Planning and Policies to Mitigate Climate Change: Evidence from a Pakistani City. Urban Clim. 2024, 56, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Cheong, J.C.; Lee, J.S.H.; Tan, J.K.N.; Chiam, Z.; Arora, S.; Png, K.J.Q.; Seow, J.W.C.; Leong, F.W.S.; Palliwal, A.; et al. Home Gardening in Singapore: A Feasibility Study on the Utilization of the Vertical Space of Retrofitted High-Rise Public Housing Apartment Buildings to Increase Urban Vegetable Self-Sufficiency. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Leung, M.K.; Poon, D.; Xiang, C. Integrating Vertical Farm into Low-Carbon High-Rise Building in High-Density Context: A Design Case Study in Hong Kong. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, F.; Egerer, M.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Navas-Gracia, L. Urban Gardening in a Changing Climate: A Review of Effects, Responses and Adaptation Capacities for Cities. Agriculture 2023, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galagoda, R.U.; Jayasinghe, G.Y.; Halwatura, R.U.; Rupasinghe, H.T. The Impact of Urban Green Infrastructure as a Sustainable Approach towards Tropical Micro-Climatic Changes and Human Thermal Comfort. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, V.; Blythe, C.; Caputo, S.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Specht, K.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Cohen, N.; Poniży, L.; Fedeńczak, K. “We Have Been Part of the Response”: The Effects of COVID-19 on Community and Allotment Gardens in the Global North. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 732641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Yue, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y. Community Gardens in China: Spatial Distribution, Patterns, Perceived Benefits and Barriers. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden to Vegetable Garden “Original Intention” Warms People’s Hearts—Government Transparency. Available online: http://www.qinghai.gov.cn/zwgk/system/2021/08/02/010389696.shtml (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- The “Shared Vegetable Garden” in Xicheng Niujie has Come to Pursue the Cultivation of Youth _ Local _ CHINA Xizang. Available online: http://www.tibet.cn/cn/Instant/local/202408/t20240813_7671295.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- A New Top-Down Governance Approach to Community Gardens: A Case Study of the “We Garden” Community Experiment in Shenzhen, China. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2413-8851/6/2/41 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Media Report (China Green Times) | Beijing will Build 100 Community Micro Gardens this Year. Available online: http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU5Mzg0MzMyMQ==&mid=2247541300&idx=2&sn=c4aab2ee54923b5d3ad5b4bcc5300e1f&chksm=ffc803db7ac146d575558588aba567866f2a00d57f72b7803b9938f3780c242ffa1ddf2aa0f9#rd (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- ‘Neighborly Door’ Clears the Blockade of Community Co governance—Society and Rule of Law—People’s Daily Online. Available online: http://society.people.com.cn/n1/2023/1027/c1008-40104431.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Reply to Proposal No. 0577 of the Third Session of the 16th Municipal People’s Congress. Available online: https://lhsr.sh.gov.cn/jytabl/20250410/c18a62227c6943e1aec84fbde5884a30.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- The Beijing Municipal Bureau of Landscape and Greening, in Conjunction with the Municipal Planning Commission, is Accelerating the Implementation of the “Beijing Garden City Special Plan (2023–2035)”. Available online: https://yllhj.beijing.gov.cn/zwgk/zwxx/202407/t20240719_3753388.shtml (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Hassan, R.; et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being—Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59726-040-4. [Google Scholar]

- Helen; Gasparatos, A. Ecosystem Services Provision from Urban Farms in a Secondary City of Myanmar, Pyin Oo Lwin. Agriculture 2020, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Diemont, S.; Selfa, T.; Rakow, D. Gathering a Bountiful Harvest: The Impacts of Cultural Ecosystem Service Experiences on Management Practices and Agrobiodiversity in Urban Community Gardens. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, J.; Egerer, M. Cultivating Nut Tree Species in Urban Community Gardens in Germany: Motivations, Challenges, and Opportunities. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2025, 40, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, S.S.; Siebert, S.J.; Du Toit, M.J.; Barthel, S.; Mishra, S.; Cornelius, S.F.; Davoren, E. Garden Ecosystem Services of Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of Health Clinic Gardens as Social-Ecological Systems. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Clarke, M.; Campbell, C.G.; Chang, N.-B.; Qiu, J. Public Perceptions of Multiple Ecosystem Services from Urban Agriculture. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 251, 105170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.; Falagán, N.; Hardman, C.A.; Kourmpetli, S.; Liu, L.; Mead, B.R.; Davies, J.A.C. Ecosystem Service Delivery by Urban Agriculture and Green Infrastructure—A Systematic Review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 54, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caneva, G.; Cicinelli, E.; Scolastri, A.; Bartoli, F. Guidelines for Urban Community Gardening: Proposal of Preliminary Indicators for Several Ecosystem Services (Rome, Italy). Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Egerer, M.H. Global Social and Environmental Change Drives the Management and Delivery of Ecosystem Services from Urban Gardens: A Case Study from Central Coast, California. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 60, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Camps-Calvet, M.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Barthel, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Stewardship of Urban Eco system Services: Understanding the Value(s) of Urban Gardens in Barcelona. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 170, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lim, M.S.; Richards, D.R.; Tan, H.T.W. Utilization of the Food Provisioning Service of Urban Community Gardens: Current Status, Contributors and Their Social Acceptance in Singapore. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Sato, Y.; Morimoto, H. Public–Private Collaboration in Allotment Garden Operation Has the Potential to Provide Ecosystem Services to Urban Dwellers More Efficiently. Paddy Water Environ. 2019, 17, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftcioglu, G.C. Social Preference-Based Valuation of the Links between Home Gardens, Ecosystem Services, and Human Well-Being in Lefke Region of North Cyprus. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Chou, R. The Impact and Future of Edible Landscapes on Sustainable Urban Development: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Cadaval, S.; Wallace, C.; Anderson, E.; Egerer, M.; Dinkins, L.; Platero, R. Factors That Enhance or Hinder Social Cohesion in Urban Greenspaces: A Literature Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukharta, O.; Huang, I.; Vickers, L.; Navas-Gracia, L.; Chico-Santamarta, L. Benefits of Non-Commercial Urban Agricultural Practices-A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavan, M.; Schmutz, U.; Williams, S.; Corsi, S.; Monaco, F.; Kneafsey, M.; Guzman Rodriguez, P.A.; Čenič-Istenič, M.; Pintar, M. The Economic Performance of Urban Gardening in Three European Cities—Examples from Ljubljana, Milan and London. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.M.; Leslie, T.W.; Drinkwater, L.E. Agroecological and Social Characteristics of New York City Community Gardens: Contributions to Urban Food Security, Ecosystem Services, and Environmental Education. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 763–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, Y.H.; Zhou, Z.X. Community Garden Construction Based on Natural Education—Taking “The Kids’ Garden” in Hunan Agricultural University as the Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 35, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Yin, K.L.; Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Mao, J.Y. Cooperative Landscape—A Case Study of the Experiment of Integrating Public Space Renewal and Social Governance of Community Gardens in Shanghai. Archit. J. 2022, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, R.J. How to Write a Systematic Literature Review: A Guide for Medical Students. Natl. AMR Foster. Med. Res. 2013, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Han, M. Pocket Parks in English and Chinese Literature: A Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.; Maye, D.; Pearson, D. Developing “Community” in Community Gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, C.; Grieger, J.A.; Kalamkarian, A.; D’Onise, K.; Smithers, L.G. Community Gardens and Their Effects on Diet, Health, Psychosocial and Community Outcomes: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, D.; Gray, T.; Sweeting, J.; Kingsley, J.; Bailey, A.; Pettitt, P. A Systematic Review Protocol to Identify the Key Benefits and Associated Program Characteristics of Community Gardening for Vulnerable Populations. IJERPH 2020, 17, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement | Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Wu, J.; Tang, L.; Zheng, F.; Chen, X.; Li, L. A Review of the Last Decade: Pancreatic Cancer and Type 2 Diabetes. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 130, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Duan, X.; Liu, H.; Meng, L. Visual Analysis of Research Progress on the Impact of Cadmium Stress on Horticultural Plants over 25 Years. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, W.; Li, X.; Xu, B. Visualization Analysis of Research on Inefficient Stock Space by Mapping Knowledge Domains. Buildings 2025, 15, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; He, F.; Li, S.; Lu, H.; Zhang, R. Contemporary Urban Agriculture in European and Chinese Regions: A Social-Cultural Perspective. Land 2024, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, S.; Shi, Q.; Fang, Y. A Review of Ecosystem Services Based on Bibliometric Analysis: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Fan, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, K.; Wu, S.; Zhu, G.; Jiang, P.; Guo, W. Research Review on Land Development Rights and Its Implications for China’s National Territory Spatial Planning. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Journal Citation Reports 2024 Statistics | Clarivate. Available online: https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-funding-analytics/journal-citation-reports/infographic/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Zhao, X. A Scientometric Review of Global BIM Research: Analysis and Visualization. Autom. Constr. 2017, 80, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personalized Homepage. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kns8s/?classid=YSTT4HG0 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Hung, K.; Wang, S.; Denizci Guillet, B.; Liu, Z. An Overview of Cruise Tourism Research through Comparison of Cruise Studies Published in English and Chinese. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guan, Y. International Youth Football Research Developments: A CiteSpace-Based Bibliometric Analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Xiong, K.; Fu, Y.; Yu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, P. Research Progress on Eco-Product Value Realization and Rural Revitalization and Its Inspiration for Karst Desertification Control: A Systematic Literature Review between 1997 and 2023. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1420562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Calvet, M.; Langemeyer, J.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Gardens in Barcelona, Spain: Insights for Policy and Planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, A.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Sondermann, M.; Münderlein, D. Placemaking in Action: Factors That Support or Obstruct the Development of Urban Community Gardens. Sustainability 2020, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastola, A.; Cozzi, M.; Viccaro, M.; Grippo, V.; Romano, S.; Kawakami, J.; Shimpo, N. 25. Exploring urban gardening experiences in Europe and Asia: Rome vs Tokyo. In Proceedings of the Green Metamorphoses: Agriculture, Food, Ecology, Perugia, Italy, 2018; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F. Multitemporal Geospatial Evaluation of Urban Agriculture and (Non)-Sustainable Food Self-Provisioning in Milan, Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C. What Gardens Grow: Outcomes from Home and Community Gardens Supported by Community-Based Food Justice Organizations. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Valuation of Allotment Gardens in Peri-Urban Degraded Agroecosystems: The Role of Citizens’ Preferences in Spatial Planning—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2210670721000639 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Speak, A.F.; Mizgajski, A.; Borysiak, J. Allotment Gardens and Parks: Provision of Ecosystem Services with an Emphasis on Biodiversity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scartazza, A.; Mancini, M.L.; Proietti, S.; Moscatello, S.; Mattioni, C.; Costantini, F.; Di Baccio, D.; Villani, F.; Massacci, A. Caring Local Biodiversity in a Healing Garden: Therapeutic Benefits in Young Subjects with Autism. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 47, 126511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, T.T. Edible Landscape Construction for “Peacetime and Wartime Use” Community—Thinking Based on Infectious Disease Prevention and Control. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.T.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhou, Z.X. The Development and Function Overview on Community Garden in the United States. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2016, 55, 2820–2823+2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Yin, K.B.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y. New Approaches to Community Garden Practices in High-density High rise Urban Areas: A Case Study of Shanghai KIC Garde. J. Community Plan. 2017, 9, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.W.; Zhou, H.D.; Wang, X.R. The Construction Strategy of Community Gardens in Beijing from the per-Spective of Edible Landscape—A Case Study of Typical Community Gardens in the United States. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2021, 06, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.H.; Li, P.; Yang, J.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.Q. Development of Community Gardens in Israel and Its En-Lightenment to China. North. Hortic. 2019, 01, 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.W. Study on the Construction Strategies of Urban Community Garden in Response to Nature-Deficit Disorder in Children. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.R.; Xie, B.; Xie, S.Y. A Preliminary Study on the Application of Urban Organic Agriculture Based on Edible Landscape. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2019, 47, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Urquijo, J.; Gómez Villarino, M.; García, A.I. Key Insights of Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Urban Development. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 45, 1441–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Meerow, S.; Turner, B.L. Planning Urban Community Gardens Strategically through Multicriteria Decision Analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, E.I.; Collins, C.M. Urban Agriculture: Declining Opportunity and Increasing Demand—How Observations from London, U.K., Can Inform Effective Response, Strategy and Policy on a Wide Scale. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolo, F. The Social and Environmental Value of Public Urban Food Forests: The Case Study of the Picasso Food Forest in Parma, Italy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 45, 126225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Home Gardening and Urban Agriculture for Advancing Food and Nutritional Security in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepacki, P.; Kujawska, M. Urban Allotment Gardens in Poland: Implications for Botanical and Landscape Diversity. J. Ethnobiol. 2018, 38, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.A.; Stoelzle Midden, K. Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Vegetable Production on Green Roofs. Agriculture 2018, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.C.; Nadot, S.; Prévot, A.-C. Specificities of French Community Gardens as Environmental Stewardships. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, art28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.W.; Jenerette, G.D. Biodiversity and Direct Ecosystem Service Regulation in the Community Gardens of Los Angeles, CA. Landsc. Ecol 2015, 30, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.C.; Egerer, M.H.; Fouch, N.; Clarke, M.; Davidson, M.J. Comparing Community Garden Typologies of Baltimore, Chicago, and New York City (USA) to Understand Potential Implications for Socio-Ecological Services. Urban Ecosyst 2019, 22, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Keim, J.; Engelmann, R.; Kraemer, R.; Siebert, J.; Bonn, A. Ecosystem Services of Allotment and Community Gardens: A Leipzig, Germany Case Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yan, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wen, J. Research on the Development Countermeasures of Urban Community Garden in the Post-Epidemic Era. Urban. Archit. 2021, 18, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.C.; Gu, Z.N.; Shen, Y. Review and Enlightenment of Study on the Health Benefits of Community Garden Abroad. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. The Value and Function of Community Garden in Urban Renewal Design. Contemp. Hortic. 2020, 02, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Research on the Design Strategy of Open Space in Urban Residential Community Based on the Concept of Health Promotion. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhou, Z.X.; Xiong, H.; Wang, W. Construction of Children’s Community Garden Based on Urban Agriculture: Taking the Kid’s Garden in the Campus of Hunan Agricultural University for an Example. J. Urban Stud. 2017, 38, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Szczepańska, M.; Kacprzak, E.; Fox-Kämper, R. Between Food Growing and Leisure: Contemporary Allotment Gardeners in Western Germany and Poland. Die ERDE 2021, 152, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Egerer, M.; Nuttman, S.; Keniger, L.; Pettitt, P.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gray, T.; Ossola, A.; Lin, B.; Bailey, A.; et al. Urban Agriculture as a Nature-Based Solution to Address Socio-Ecological Challenges in Australian Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, C.; Randall, L.; Wang, S.; Aguiar Borges, L. Monitoring the Contribution of Urban Agriculture to Urban Sustainability: An Indicator-Based Framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, A.T.; Liste, V.; Seidel, C.; Matscheroth, L.; Otto, M.; Meier, F.; Fenner, D. How Cool Are Allotment Gardens? A Case Study of Nocturnal Air Temperature Differences in Berlin, Germany. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, S.; Schmidt, K.; Kühn, P.; Scholten, T. Engaging with Urban Green Spaces—A Comparison of Urban and Rural Allotment Gardens in Southwestern Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg Dyg, P.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C.J. Community Gardens and Wellbeing amongst Vulnerable Populations: A Thematic Review. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.; Fouch, N.; Anderson, E.C.; Clarke, M. Socio-Ecological Connectivity Differs in Magnitude and Direction across Urban Landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. The Motivation of Urban Gardens in Mountain Areas. Case South Tyrol. Sustain. 2020, 12, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Dean, A.; Barry, V.; Kotter, R. Places of Urban Disorder? Exposing the Hidden Nature and Values of an English Private Urban Allotment Landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Salvador, G.; De Luis, A.; Pérez, J.J.; Sanchis-Ibor, C. Greening the post crisis. Collectivity in private and public community gardens in València (Spain). Cities 2019, 92, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middle, I.; Dzidic, P.; Buckley, A.; Bennett, D.; Tye, M.; Jones, R. Integrating Community Gardens into Public Parks: An Innovative Approach for Providing Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E.; Heland, L.; Grohmann, D. Learning from the Gardeners of the Oldest Community Garden in Seattle: Resilience Explained through Ecosystem Services Analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S. The Potential of ‘Urban Green Commons’ in the Resilience Building of Cities. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram-Bijkerk, D.; Otte, P.; Dirven, L.; Breure, A.M. Indicators to Support Healthy Urban Gardening in Urban Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; DuBois, B.; Tidball, K.G. Refuges of Local Resilience: Community Gardens in Post-Sandy New York City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.R.; Yu, W.X.; Gao, W. The Current Status and Prospect of Edible Landscape Research in Urban Area. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.Y. Explore the Implementation Ways of Community Governance Through the Renewal of Urban Stock Green Space——Taking the Construction of Chuangzhi Agricultural Park in Shanghai as an Example. City House 2019, 26, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Shi, W.Z. Practice and Exploration of Community Farm from the Perspective of Shared Space—Taking the Phase II Landscape Project of Yantai Rongchuang Erhai Project as an Example. Bus. Lux. Travel 2019, 206–207. [Google Scholar]

- Breuste, J.H.; Artmann, M. Allotment Gardens Contribute to Urban Ecosystem Service: Case Study Salzburg, Austria. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2015, 141, A5014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, J.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Specht, K.; Fernández, J.A.; Bañón, S.; Orsini, F.; Magrefi, F.; Bazzocchi, G.; Halder, S.; Martens, D.; et al. Sustainable Community Gardens Require Social Engagement and Training: A Users’ Needs Analysis in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diduck, A.P.; Raymond, C.M.; Rodela, R.; Moquin, R.; Boerchers, M. Pathways of Learning about Biodiversity and Sustainability in Private Urban Gardens. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liu, L.Y. Practice of Participation Construction in Shanghai Community Gardens from Child-Friendly Perspective. Landsc. Des 2022, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.L. Research on Building of Community Garden in the City Based on the Children’s Natural Education—Case Study of Knowledge & Innovation Community Garden in Shanghai. Master’s Thesis, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L. Research on the Design of Children ’s Outdoor Activity Space in Residential Area from the Perspective of Natural Education. Shandong Jianzhu University. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Asuero, R.P. Public versus Private: Juxtaposing Urban Allotment Gardens as Multifunctional Nature-Based Solutions. Insights from Seville. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniży, L.; Latkowska, M.J.; Breuste, J.; Hursthouse, A.; Joimel, S.; Külvik, M.; Leitão, T.E.; Mizgajski, A.; Voigt, A.; Kacprzak, E.; et al. The Rich Diversity of Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe: Contemporary Trends in the Context of Historical, Socio-Economic and Legal Conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.H.; Philpott, S.M.; Bichier, P.; Jha, S.; Liere, H.; Lin, B.B. Gardener Well-Being along Social and Biophysical Landscape Gradients. Sustainability 2018, 10, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. A Landscape Architecture System Combining Public Health with Community Units. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusciano, V.; Civero, G.; Scarpato, D. Social and Ecological High Influential Factors in Community Gardens Innovation: An Empirical Survey in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, T.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Sousa, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Freire, E. Evidence on the Contribution of Community Gardens to Promote Physical and Mental Health and Well-Being of Non-Institutionalized Individuals: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Brieger, H. Does Urban Gardening Increase Aesthetic Quality of Urban Areas? A Case Study from Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, N.; Simpson, T.; Orlove, B.; Dowd-Uribe, B. Environmental and Social Dimensions of Community Gardens in East Harlem. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 183, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobolo, A.; Mkabela, Q. Traditional Knowledge Transfer of Activities Practised by Zulu Women to Manage Medicinal and Food Plant Gardens. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2006, 23, 1. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2989/10220110609485889 (accessed on 25 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Grohmann, D. Integrating Community Gardens into Urban Parks: Lessons in Planning, Design and Partnership from Seattle. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.P. Public Pedagogies of Edible Verge Gardens: Cultivating Streetscapes of Care. Policy Futures Educ. 2019, 17, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.H.H.; Neo, H. “Community in Bloom”: Local Participation of Community Gardens in Urban Singapore. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisbon Municipality. Green Surge. 2015. Available online: Https://Greensurge.Eu/Products/Case-Studies/Case_Study_Portrait_Lisbon.Pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- City of Sydney. Social Sustainability Policy & Action Plan 2018–2028. 2018. Available online: https://meetings.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/documents/s10301/attachment%20a%20-%20a%20city%20for%20all%20social%20sustainability%20policy%20and%20action%20plan%202018-2028.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Mayor of London. The London Plan 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/the_london_plan_2021.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Filkobski, I.; Rofè, Y.; Tal, A. Community Gardens in Israel: Characteristics and Perceived Functions. Urban Estry Urban Green. 2016, 17, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Central City Work Conference was held in Beijing, and Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang delivered important speeches. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2015-12/22/content_5026592.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Du, Y.L. A Study of Xi Jinping’s New Development Concept. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, Z. Green Urban Renewal: An Important Direction for Urban Development in the New Era. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 43, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.C.; Li, T.L.; Yan, G.R. A Study on the Influence of public Acceptance of Community Garden in Haikou City Based on SEM. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 45, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Cui, L.N.; Wang, Y.C. Research on the Practice of Community Micro-renewal in the New Era from the Perspective of Social Network: A Case Study of Community Gardens in Shanghai. Art Des. 2023, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Pan, D.Q. Research on Community Garden Practice and Public Health Promotion Under the Background of the Epidemic. Landsc. Archit. Acad. J. 2023, 40, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Huang, S.H.; Guo, Y.T.; Zeng, S.J. Exploration of the Combination Construction Model of Edible Com munity Gardens in Southwest China. Contemp. Hortic. 2023, 46, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Keshavarz, N.; Benson, M.; Caputo, S.; Noori, S.; Voigt, A. Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mwakiwa, E.; Maparara, T.; Tatsvarei, S.; Muzamhindo, N. Is Community Management of Resources by Urban Households, Feasible? Lessons from Community Gardens in Gweru, Zimbabwe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrl, I.; Moschitz, H.; Cavin, J.S. The Role of Food Gardening in Addressing Urban Sustainability—A New Frame work for Analysing Policy Approaches. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. P-Patch Gardening. 2023. Available online: Https://Www.Seattle.Gov/Neighborhoods/p-Patch-Gardening (accessed on 17th November 2023).

- Sartison, K.; Artmann, M. Edible Cities—An Innovative Nature-Based Solution for Urban Sustainability Transformation? An Explorative Study of Urban Food Production in German Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover Nature School. New Year’s Address 2023—SEEDINGARDENS Rebuilding Neighborhoods. 2023. Available online: Https://Mp.Weixin.Qq.Com/s/y23RtOBEOmMjelz_iWGU6w (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Gittleman, M.; Farmer, C.J.Q.; Kremer, P.; McPhearson, T. Estimating Stormwater Runoff for Community Gardens in New York City. Urban Ecosyst 2017, 20, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Egerer, M.; Bichier, P.; Cohen, H.; Liere, H.; Lin, B.; Lucatero, A.; Philpott, S.M. Multiple Ecosystem Service Synergies and Landscape Mediation of Biodiversity within Urban Agroecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azunre, G.A.; Amponsah, O.; Peprah, C.; Takyi, S.A.; Braimah, I. A Review of the Role of Urban Agriculture in the Sustainable City Discourse. Cities 2019, 93, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshad, A.B. Community Gardens: An Investment in Social Cohesion, Public Health, Economic Sustainability, and the Urban Environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Foenander, E.; Bailey, A. “It’s about Community”: Exploring Social Capital in Community Gardens across Melbourne, Australia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Participatory Action Research on the Impact of Community Gardening in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Investigating the Seeding Plan in Shanghai, China. IJERPH 2021, 18, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Central People’s Government. Opinions on Comprehensively Strengthening Labor Education in Universi ties, Middle Schools and Primary Schools in the New Era. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-03/26/content_5495977.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on Issuing the Compulsory Education Curriculum Program and Curriculum Standards (2022 Version). Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/a26/s8001/202204/t20220420_619921.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- He, B.; Zhu, J. Constructing Community Gardens? Residents’ Attitude and Behaviour towards Edible Landscapes in Emerging Urban Communities of China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; Cohen, N.; Israel, M.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Poniży, L.; Schoen, V.; Caputo, S.; Kirby, C.K.; et al. The Socio-Cultural Benefits of Urban Agriculture: A Review of the Literature. Land 2022, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldivar-Tanaka, L.; Krasny, M.E. Culturing Community Development, Neighborhood Open Space, and Civic Agriculture: The Case of Latino Community Gardens in New York City. Agric. Hum. Values 2004, 21, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Wende, W. Physically Apart but Socially Connected: Lessons in Social Resilience from Community Gardening during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.R.; Jin, H.X.; Yan, Y. Evolution Process, Hotspots and Trends of Community Gardens in Recent 20 Years. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 28, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.L.; Yao, L.S. Exploration on Micro Renewal Governance Mechanism of Micro Garden Community Based on Community Building. Landsc. Des. 2022, 01, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Aida, N.; Sasidhran, S.; Kamarudin, N.; Aziz, N.; Puan, C.L.; Azhar, B. Woody Trees, Green Space and Park Size Improve Avian Biodiversity in Urban Landscapes of Peninsular Malaysia. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, V.; Cortet, J.; Baldantoni, D.; Bellino, A.; Dubs, F.; Nahmani, J.; Strumia, S.; Maisto, G. Collembolan Biodiversity in Mediterranean Urban Parks: Impact of History, Urbanization, Management and Soil Characteristics. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 119, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lima, M.F.; McLean, R.; Sun, Z. Exploring Preferences for Biodiversity and Wild Parks in Chinese Cities: A Conjoint Analysis Study in Hangzhou. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; Lang, T.; Barling, D. London’s Food Policy: Leveraging the Policy Sub-System, Programme and Plan. Food Policy 2021, 103, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witheridge, J.; Morris, N.J. An Analysis of the Effect of Public Policy on Community Garden Organisations in Edinburgh. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokić, V.; Ristić Trajković, J.; Furundžić, D.; Krstić, V.; Stojiljković, D. Urban Garden as Lived Space: Informal Gardening Practices and Dwelling Culture in Socialist and Post-Socialist Belgrade. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, R. Co-Creating Community Gardens on Untapped Terrain—Lessons from a Transdisciplinary Planning and Participation Process in the Context of Municipal Housing in Vienna. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| English Publications | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | City/Town | Number |

| USA | Seattle, Phoenix, New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Monterey, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Los Angeles, Laramie, Carbondale, Akron, Cleveland, Miami-Dade County, Denver, Appleton, Boulder, Washington | 33 |

| Germany | Karlsruhe, Leipzig, Dortmund, Aachen, Düsseldorf, Essen, Hannover, Kassel, Berlin, Kassel, Ruhr Area, Braunschweig, Munich | 21 |

| Italy | Parma, Milan, Bologna, Padua, Naples, Rome, Gallipoli | 15 |

| UK | Manchester, London, West Midlands, Ayr, Greenock | 13 |

| France | Grand Nancy, Marseilles, Nantes, Paris, Montreuil, Pré-Saint-Gervais, Bordeaux | 10 |

| Spain | Sevilla, Barcelona, Murcia, Cartagena, Valencia, Sant Feliu de Llobregat | 9 |

| Poland | Poznan, Warsaw, Gorzów Wlkp, Wroclaw, Katowice, Krakow | 9 |

| Australia | Perth, Melbourne, Brisbane, Tasmania, Sydney, Hobart | 7 |

| South Africa | Rustenburg, Madibeng, Moretele, Moses Kotane, Elundini, Mbhashe, Mbizana, Ntabankulu, Raymond Mhlaba, Umzimvubu, Potchefstroom | 5 |

| Japan | Osaka, Tokyo | 4 |

| Canada | Winnipeg, Toronto | 4 |

| Austria | Salzburg | 3 |

| China | Changsha, Hangzhou | 3 |

| Iran | 3 | |

| Portugal | Lisbon | 2 |

| New Zealand | Christchurch | 2 |

| Switzerland | Zurich | 2 |

| Czech Republic | Prague | 2 |

| Sweden | Stockholm | 2 |

| Mexico | 1 | |

| Belgium | 1 | |

| Slovenia | Ljubljana | 1 |

| Denmark | Arhus | 1 |

| Hungary | Budapest | 1 |

| Estonia | Paide, Marseille | 1 |

| Norway | Oslo | 1 |

| Singapore | 1 | |

| Chinese Publications | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Province | City | Number |

| China | Shanghai | 23 | |

| Beijing | 10 | ||

| Guangdong | Shenzhen, Foshan | 5 | |

| Hunan | Changsha | 4 | |

| Tianjin | 3 | ||

| Shandong | Weifang, Yantai | 2 | |

| Zhejiang | Shaoxing | 2 | |

| Chongqing | 2 | ||

| Fujian | Fuzhou | 2 | |

| Hainan | Haikou | 2 | |

| Sichuan | Leshan | 1 | |

| Xinjiang | Wulumuqi | 1 | |

| Guangxi | Nanning | 1 | |

| Henan | 1 | ||

| Wuhan | 1 | ||

| Nanjing | 1 | ||

| Chongqing | 1 | ||

| USA | 10 | ||

| Germany | 6 | ||

| England | 4 | ||

| Australia | 3 | ||

| Singapore | 2 | ||

| Israel | 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, X.; Yue, X.; Shu, P. Comprehensive Review of Ecosystem Services of Community Gardens in English- and Chinese-Language Literature. Buildings 2025, 15, 2137. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122137

Ding X, Zhang H, Fan X, Zhang X, Yue X, Shu P. Comprehensive Review of Ecosystem Services of Community Gardens in English- and Chinese-Language Literature. Buildings. 2025; 15(12):2137. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122137

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Xiaoying, Haotian Zhang, Xiaoxiao Fan, Xiaoyu Zhang, Xiaopeng Yue, and Ping Shu. 2025. "Comprehensive Review of Ecosystem Services of Community Gardens in English- and Chinese-Language Literature" Buildings 15, no. 12: 2137. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122137

APA StyleDing, X., Zhang, H., Fan, X., Zhang, X., Yue, X., & Shu, P. (2025). Comprehensive Review of Ecosystem Services of Community Gardens in English- and Chinese-Language Literature. Buildings, 15(12), 2137. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122137