1. Introduction

Architectural studios play a crucial role in shaping the built environment and driving design innovation. However, traditional modes of representation, such as cardboard models and technical drawings, fall short of capturing the complex and multi-layered nature of architectural contexts. To effectively conceptualize the contextual milieu, more expansive and inclusive representational methodologies are needed.

Critiques of traditional models center on their tendency to limit material exploration and hinder creative ideation. This procedural constraint results in a representation that reduces originality to a singular entity, distorting the genesis of designs that are attuned to, or emanating from, the contextual backdrop and espousing sustainable principles. To fully realize its potential as an incubator for a nuanced, context-sensitive, and sustainable design paradigm, the architectural studio must transcend the confines of customary representation.

This research explores the evolving approach in architectural studios, highlighting the importance of contextualization and environmental information in the development and expression of design. Rather than relying on restrictive techniques and conventions, modern practices prioritize experimentation with materials and methodologies as essential components of the studio experience. This shift fosters a more dynamic and collaborative understanding of the context, empowering architects to make informed and thoughtful design choices.

In this academic framework, it is crucial to incorporate a variety of representation methods to gain a nuanced understanding of the complex contextual nuances that influence design proposals. Material experimentation plays a pivotal role in enabling students to decode and respond to contextual complexities by exploring the latent potential of materials. This departure from reductionist approaches promises to have a significant impact on a one-to-one scale, where responsiveness to context goes beyond traditional paradigms.

The proposed studio approach is founded on methodologies that encourage a lively and interactive understanding of the surrounding environment. This shift away from static representations goes beyond the norm, enabling students to interact with the context as a dynamic and living entity. In light of this, the complete paper will delve into the process, method, content, and outcomes of the architectural design studio’s exploration of tectonic ecological housing concepts during the 2nd semester of Gebze Technical University’s Department of Architecture in the Fall semester of 2023–2024.

To sum up, the architectural studio’s transformative ethos represents a significant shift in how designers engage with their surroundings. By adopting contemporary methodologies and experimenting with materials, they break free from traditional representation and create a more dynamic, inclusive, and sustainable design practice. This evolution enhances the studio’s creative potential while ensuring that architectural innovations blend seamlessly with the built environment.

This study contributes to the growing body of research on architectural design education by integrating phenomenological spatial experiences and material experimentation into the early stages of studio learning. It addresses a notable gap in conventional studio practices, where material awareness and contextual responsiveness are often overlooked in favor of abstract formal exercises. Unlike similar studies that primarily focus on representational techniques, this research introduces a dynamic, experiential, and tectonic approach, aiming to cultivate a deeper understanding of the material and environmental dimensions of architectural design.

2. A Comprehensive Approach for Architectural Design Studios

Conceptual framework architectural design studios, due to their multifaceted nature and relationships with various disciplines within architectural education, constantly renew their dynamics, evolving and transforming alongside the dynamics of the times to capture current issues and develop proposals for the future. As in the exploration of the constructed tectonic approach, the studio framework also aligns with Holl’s perspective [

1], emphasizing architecture as a haptic field shaped by the body’s sensory engagement with spatiality and temporality [

2]. This aligns with Pallasmaa’s argument [

3] that architecture should be understood through multi-sensory experiences, rather than purely visual terms.

Within the scope of architectural education, it becomes crucial for contemporary design studio methods and their contributing components to nourish a new conceptual framework for studio education. Within the conceptual framework developed in this article, the architectural design studio environment, its actors, roles, and interaction practices, as well as design tools, are reexamined in the context of current changes and needs, aiming to exemplify new forms of learning and teaching. As emphasized by Pombo, Bervoets, and De Smet [

4], phenomenological approaches in design education help students integrate experiential understanding into architectural analysis. Additionally, Andersen [

5] highlights that embodied environmental communication fosters meaningful architectural situations, further enriching the pedagogical approach of design studios.

In the formation of the conceptual framework, architectural design decisions are considered within the combination of conceptual and contextual approaches. The nature of the site is explored and defined through conceptual approaches, allowing the design to transcend restrictive influences and consider all aspects of physical, social, cultural, and historical characteristics. In the developed conceptual framework, the content of the studio is based on describing and questioning the relationship between architecture and its cultural and social environment. These topics both define the nature of the design and constitute a part of the design process.

3. Architectural Design Studio’s Pedagogical Framework

Within the scope of the course, a dwelling will be designed in the Prince’s Islands, Istanbul during the fall semester of 2023/24. The projected building will be added to the urban texture by utilizing neglected or underused land on the islands. The project area Kınalıada (formerly known as ‘Proti’), dates back to the Byzantine period and the built environment that gives the Island its current identity has begun in the 19th century [

Figure 1] [

6]. It is possible to see the prominent styles of the previous periods throughout the Island, which attributed a summer resort identity to the Island eventually [

7].

The design focuses on the building’s characterization which will be based on a tectonic perspective developing from a touchdown. The program of the dwelling will be determined by the tutor, according to the design problems; in other words, a unique scenario will be created regarding the needs and demands of the occupants, the site, and the dynamics of the island. This follows Özçam’s phenomenological method [

8], which emphasizes the integration of sensory experiences into architectural representation and design. Moreover, Zumthor [

9] discusses how atmospheric qualities in architectural settings influence user perception, reinforcing the importance of contextual design decisions.

The overall framework of the design studio discussed above aims for architecture students in the Architectural Design 221 studio process to acquire the ability to shape residential and urban design, considering the components of human, culture, behavior, and architecture. As Koş and Gasseloğlu [

10] state, the first year of design education involves exploring architectural knowledge through the construction and deconstruction of spatial, bodily, and perceptual boundaries. Throughout this process, the goal is to evaluate and define design concepts in relation to these components. Sözen and Yavuz [

11] highlight that phenomenological experience in basic design education fosters students’ ability to interpret space dynamically, reinforcing its role in the studio process. The studio is considered as a dynamic process nourished by the concept of ‘place,’ accepting it as a fundamental component in design thinking. Each semester, the studio initiates the process with a seminar series, foreseeing its contribution to the conceptual foundation of the studio based on the chosen site and its assistance in conceptual narratives. This is followed by collective workshops, where the chosen ‘residence’ theme is explored through experiences, routines, current issues, or different perspectives, prompting a reevaluation of the concepts forming of the project. These workshops serve as the initial step in the design process where mental images derived from discussions transform into spatial manifestations.

The overall structure of the studio follows the main framework of “seminars + workshops+ studio + jury”. Within the scope of Architectural Design Studio 221, where workshops and studio activities take place, the semester-long process involved the participation of 14 students and 2 tutors. In the next section, productions, practices, and processes related to the project topic within the architectural design studio will be conveyed through the dynamics.

The methodology of this study is structured around the analysis of the architectural design process, emphasizing the sequential phases that contribute to the development of comprehensive design solutions. The study examines key activities such as scenario development, user profile creation, and the integration of function and form.

These phases are critical in guiding students from initial design intentions through to the final evaluation stage, where feedback from juries plays a crucial role. This structured approach ensures that each phase of the design process is thoroughly explored, providing a holistic understanding of how architectural concepts evolve within studio settings.

With the aim of forming the conceptual framework for the projects to be undertaken throughout the term regarding urban housing and new lifestyles, and to assist students in shaping their project narratives, the architectural design studio process commenced with a short-term collective workshop. Within the architectural design studio, which spans 14 weeks in a semester, the workshops covered 3 weeks. Initially, each student was expected to describe their spatial experiences in writing, and subsequently, groups were formed based on three designated fundamental concepts. Following the initial discussions, the objective was to establish a narrative, discuss the concepts to convey the experience, present these concepts, and engage in collaborative discussions during each session based on these presentations. The collective workshop concluded with presentations involving models that represented the three fundamental concepts. The aim at this point was to freely discuss the concepts, situations, potentials, dreams, and problems related to lifestyle descriptions, and to express all these through visualizations and models.

4. Methodology of the Study

This study employs a qualitative research methodology structured around the analysis of an architectural design studio conducted during the Fall semester of 2023–2024 at Gebze Technical University. The research explores how phenomenological spatial experiences and material experimentation can enhance the design process in early-stage studio education.

The study’s methodological approach aligns with recent perspectives on embodied environmental communication in architectural education [

5] and emphasizes the role of material-sensitive and experiential learning strategies [

12]. Within this framework, multiple thematic areas such as “Defining the Experience” and “Conceptualizing ‘Place’” were systematically explored through workshops, observations, and reflective practices [

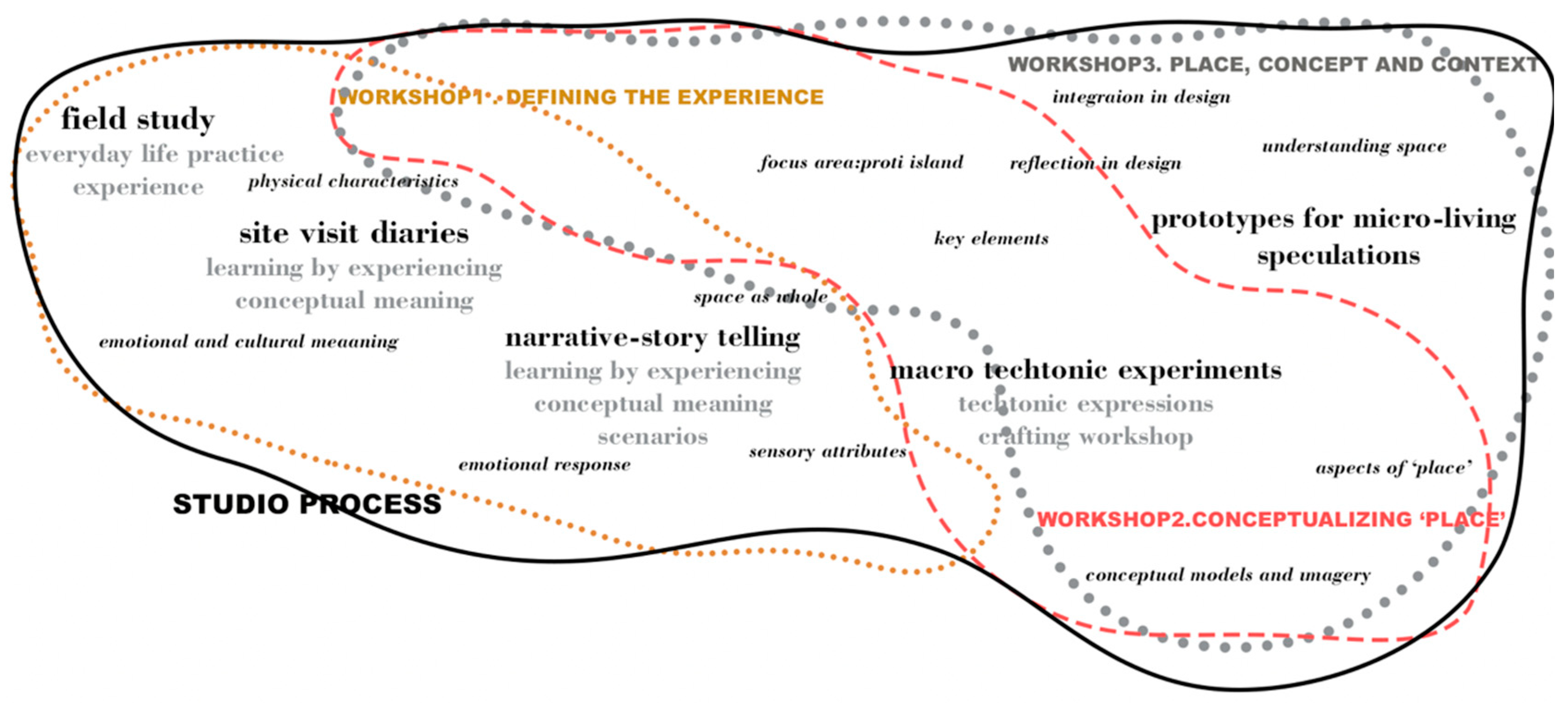

Figure 2]. A qualitative thematic analysis method was adopted to synthesize student experiences, spatial concepts, and pedagogical insights.

The diagram presents the studio process, combining observation, reflection, and experimental design. It is structured around three workshops—Defining the Experience, Conceptualizing Place, and Place, Concept and Context. The process begins with field studies and site visit diaries, where students observe everyday life and explore emotional, cultural, and physical aspects of space. Through narrative-storytelling, they transform experiences into conceptual ideas and design scenarios. It continues with macro tectonic experiments, exploring materials and spatial forms, and ends with micro-living prototypes focusing on small-scale speculative designs. The diagram reflects a creative learning cycle connecting experience to design. Organization of these thematic areas, ensuring that the analysis remained focused on the key elements identified in the workshops. By aligning the study’s methodology with the mind map, we were able to systematically explore how students integrate phenomenological experiences, personal spatial perceptions, and cultural meanings into their design practices. Doran [

13], emphasizes the significance of urban tectonics in architectural education and practice, advocating for a design approach that integrates social, economic, and environmental dynamics rather than focusing solely on physical structures. Urban design should engage with the complexities of cities rather than treating them as blank slates. Armağan [

14], examines the relationship between materiality, perception, and spatial experience, emphasizing the importance of phenomenological methods in architecture. Her research highlights how tectonic language influences material-sensitive design processes. This notion is further supported by Yorgancıoğlu and Seyman Güray [

12], who argue that alternative approaches in design education enhance students’ spatial awareness and creative processes.

Following this structured methodological framework, the participants, data collection tools, and analysis procedures were defined to guide the study systematically.

4.1. Participants

The study involved 14 second-year undergraduate students from the Department of Architecture, Gebze Technical University. 2 studio coordinators who facilitated seminars, workshops, and design critiques. Participants engaged throughout a 14-week semester-long studio course structured around the theme of “Tectonic Housing”.

4.2. Data Collection Tools

Data collection was conducted through multiple qualitative tools, including:

Participant observations during seminars, workshops, and studio sessions.

Reflective journals where students recorded personal spatial experiences and design processes.

Informal interviews and feedback sessions conducted during juries and critiques.

Analysis of design outputs such as diagrams, physical models, and narrative texts produced by students.

4.3. Data Analysis Method

A qualitative thematic analysis approach was adopted to interpret the collected data. The analysis process involved:

Categorizing spatial experiences and material explorations around key emergent themes: uniqueness, greenery, boundary, and solitude.

Interpreting workshop outputs, spatial concepts, and experiential mappings.

Synthesizing findings to identify pedagogical gains and methodological insights.

4.4. Studio Process Overview

The studio framework was organized around the following stages:

Seminars: A conceptual foundation was laid through thematic seminars focusing on tectonics, phenomenology, and contextual sensitivity.

Workshops:

- o

Workshop 1: Defining the Experience—Students analyzed personal spatial experiences and extracted emotional and physical narratives.

- o

Workshop 2: Conceptualizing Place—Group work conceptualized Kınalıada’s characteristics through site models and spatial storytelling.

- o

Workshop 3: Place, Concept, and Context—Individual studies translating environmental readings into tangible material representations.

Studio Project Development:

- o

Scenario development and user profiling guided the formation of project narratives.

- o

Functional and formal explorations through diagrams, models, and iterative design critiques.

- o

Integration of lifestyle scenarios and tectonic strategies into final spatial proposals.

Jury Evaluations: Students presented their work to instructors and external jurors. Feedback focused on spatial interpretation, material sensitivity, and context responsiveness.

5. Findings—Thematic Analysis and Pedagogical Gains

5.1. Workshop 1: Defining the Experience

The first workshop focused on students’ personal spatial experiences. Students were asked to describe spaces they had inhabited or observed, analyzing their physical, emotional, and cultural attributes. This exercise aimed to foster a deeper phenomenological understanding of space beyond its tangible characteristics, highlighting how textures, materials, atmospheres, and sensory perceptions shape spatial meaning [

14,

15]. When defining experience, a particular focus is placed on the concept of phenomenological experience. Phenomenological experience is the perception and experience of space from an individual and subjective perspective [

3]. It allows for the evaluation of space as a whole, considering both its physical and emotional dimensions. Students are expected to describe the sensory attributes of the space (textures, smells, sounds) and the feelings these attributes evoke in them. The phenomenological approach enables students to understand the space more deeply and reflect this understanding in their designs. This perspective is echoed by Pallasma [

16], who emphasizes the significance of peripheral perception in architectural experience, arguing that sensory engagement with the environment enriches the depth and authenticity of spatial understanding.

Students documented their observations of Kınalıada through reflective writings. These narratives were later categorized into four main conceptual groups: uniqueness, greenery, boundary, and solitude. Each concept reflected a particular spatial, cultural, or emotional characteristic observed on the island.

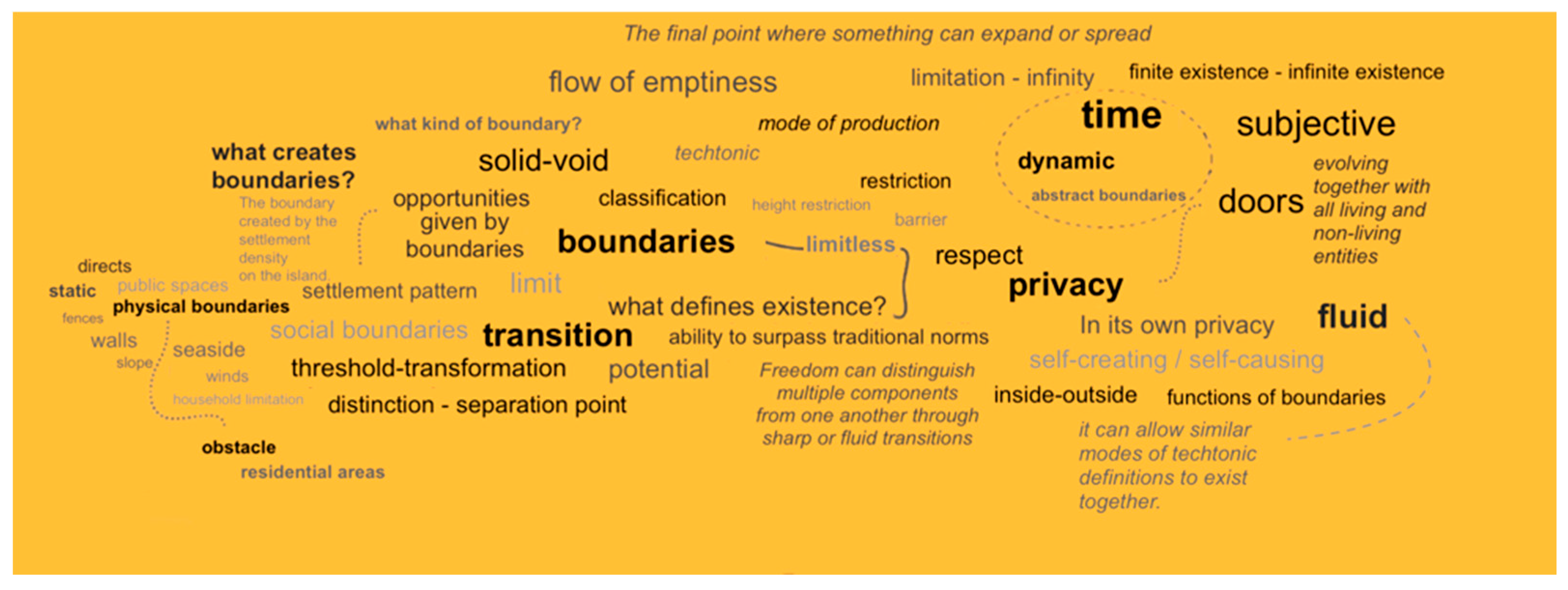

One of the student works, a mind map [

Figure 3], encapsulated the concept of boundary, illustrating thresholds, inside-outside transitions, and notions of privacy and differentiation. The analysis emphasized that spatial boundaries are not purely physical but also perceptual and emotional.

This phase reinforced the value of phenomenological experience [

3,

16] in enabling students to interpret space holistically, considering emotional, sensory, and social dimensions.

5.2. Workshop 2: Conceptualizing ‘Place’

In the second workshop, students work in groups to conceptualize the Proti Island. Reading and analyzing “place” involves discussing the integrity of culture, space, architecture, and cultural understanding for students. Therefore, incorporating “reading the island/environment” into the design education process is crucial for the conceptual foundation of the design. This involves creating conceptual models and imagery for the entire area.

Following this, the students are tasked with a group project where they design a site model that represents the four key concepts: greenery, boundary, solitude, and uniqueness.

The important aspect of this exercise is not merely to construct a physical model but to materialize spatial interpretations that are rooted in lived experiences. Based on the students’ written reflections describing their spatial experiences, four major conceptual themes—uniqueness, greenery, boundary, and solitude—were identified by the studio coordinators. These concepts emerged through a thematic synthesis of the students’ individual narratives, ensuring that the conceptual framework remained grounded in their personal phenomenological interpretations.

Each group’s design approach was expected to embody these concepts, interpreting them through collective student experiences and integrating them into the spatial and architectural characteristics of the island, thereby capturing the essence of its identity.

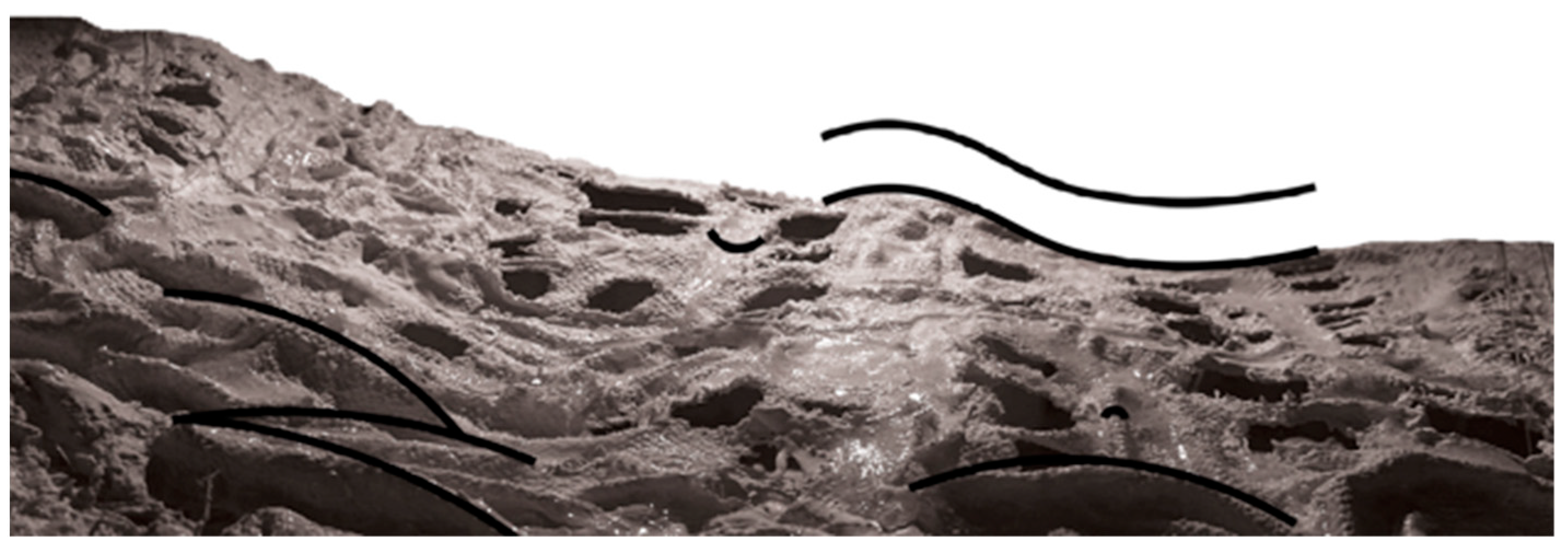

Greenery [

Figure 4]: Greenery model represents Kınalıada’s layered natural landscape, capturing organic forms and flowing paths. The textured layers evoke the island’s undulating terrain, while wavy lines suggest greenery interwoven within its natural contours.

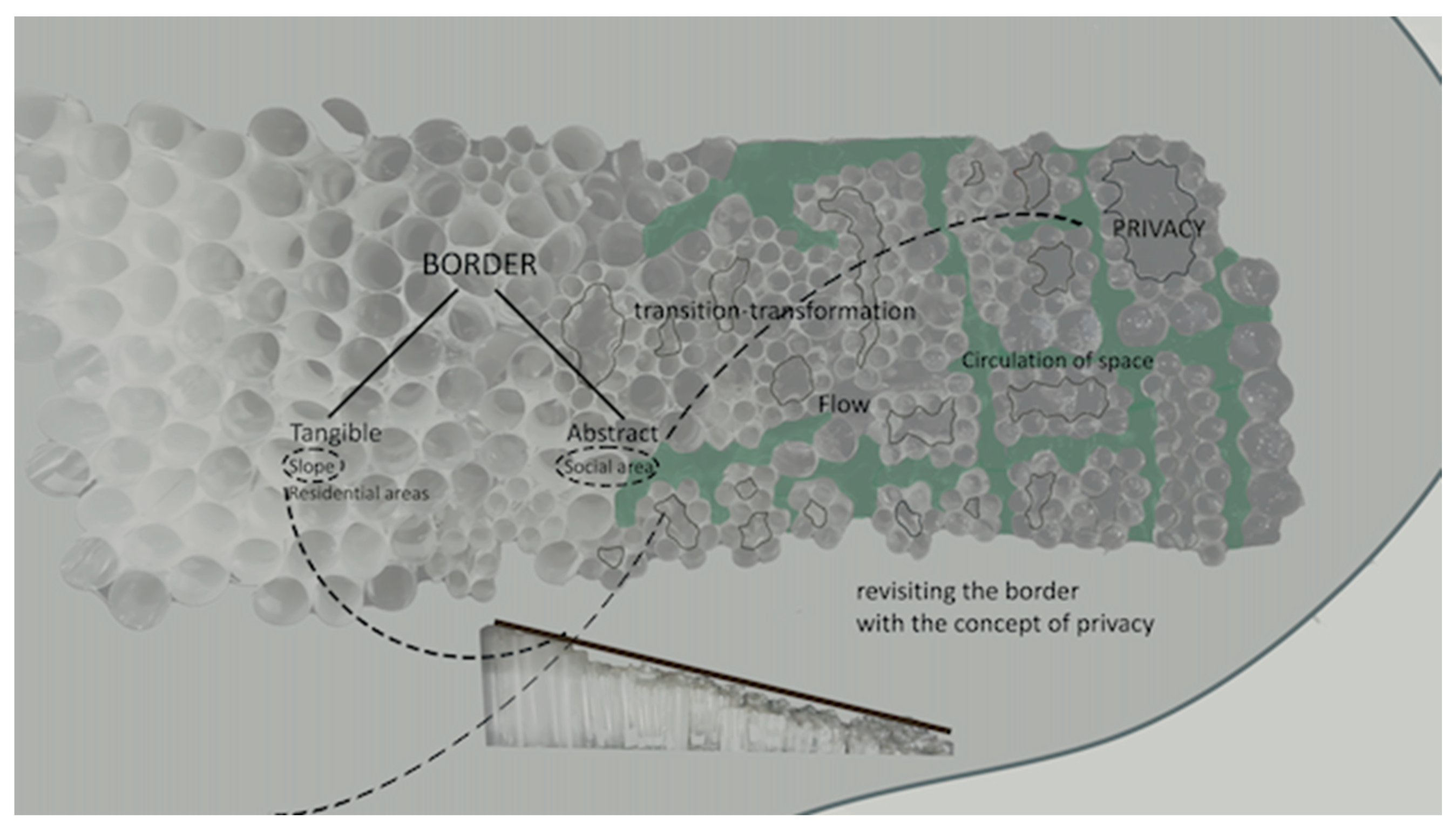

Boundary [

Figure 5]: This model conceptualizes the idea of boundaries in Kınalıada by differentiating between tangible and abstract spaces. The tangible areas represent residential zones, while abstract spaces symbolize social realms, illustrating a gradual transition from public to private. The model’s flow highlights spatial circulation, with green paths defining connectivity. This layered approach reimagines borders as flexible, transforming barriers that mediate privacy and communal interaction, reflecting Kınalıada’s spatial dynamics.

Solitude [

Figure 6]: The model reflects the concept of “solitude” in the context of Kınalıada through the gradual height variation of vertical elements, symbolizing isolation within a collective. The dense clustering of sticks at one end contrasts with sparse spacing, representing solitary presence amid a larger setting. This gradient from dense to sparse echoes the island’s spatial and social dynamics, where individual experiences of solitude blend with communal environments. The elevation variation also suggests the topography, reflecting Kınalıada’s unique layered landscape and individual spaces within a shared environment.

Uniqueness [

Figure 7]: These models conceptually reflect “uniqueness” through distinct, isolated structures that emphasize individual identity within a larger context. Each line and element stands uniquely, symbolizing independence while being part of an interconnected framework. The layers and textures highlight individuality’s persistence, suggesting distinct forms coexisting without merging into a homogeneous whole.

Through these models, students demonstrated how conceptual readings could inform spatial articulation and deepen contextual responsiveness.

5.3. Workshop 3: Place, Concept, and Context (Individual Studies)

The third workshop transitioned to individual studies where each student selected a site fragment and developed a conceptual model using new materials. Students were encouraged to translate their phenomenological insights and collective knowledge into personal spatial interventions.

Three sample projects are highlighted:

- 1.

Student [

Figure 8]—“Layering & Boundary”

Tectonic: Layered structures and linear elements emphasize spatial separation and boundaries

Planning: Uses a scenario-based analysis, integrating user movements and environmental interactions.

Conceptual: Focuses on the idea of “boundary,” addressing the physical and social divisions within the space.

- 2.

Tectonic: Grid systems and modular components highlight spatial organization.

Planning: Examines how the space is shaped within a structured and systematic order.

Conceptual: Expresses the idea of “repeatability and organization” within a spatial system.

- 3.

Student [

Figure 10]—“Nature & Spatial Integration”

Tectonic: A spatial model shaped by the integration of green spaces and natural elements.

Planning: Demonstrates how space is designed with a biophilic approach, emphasizing its connection with nature.

Conceptual: Examines the idea of “integration with nature” through architectural representation.

This stage fostered critical thinking, creativity, and the practical application of theoretical knowledge in tangible outputs.

These studies reveal how students interpret the meaning of space and translate it into physical models. Each approach is distinct yet interconnected.

Experiencing space phenomenologically involves describing the built and natural environment, which forms the focus of daily life, through dimensions, lengths, depths, materials, colors, and textures. In this direction, students redefine voids, create new routes, and develop the existing urban fragment with conceptual forms at different scales. Incorporating phenomenological experiences into projects makes the designs more human-centered and meaningful.

In summary, these workshops enable students to see space not only as a physical structure but also as a cultural and emotional experience. This process helps them develop a deeper and multidimensional understanding of space. In this context, students are redefining spaces, creating new routes, and enhancing the existing urban fragment with conceptual forms at different scales.

5.4. Transition from Workshops to Structured Studio Process

Following the completion of the workshops, the studio evolved into a structured design phase where students synthesized their experiential learnings into architectural proposals.

This phase involved three main stages:

User Profiles and Scenario Development: Students created fictional profiles based on environmental observations and cultural dynamics. Each user profile led to specific lifestyle scenarios shaping the dwelling needs and spatial programs.

Function + Form Exploration: Based on user scenarios, students developed housing strategies integrating functional layouts with tectonic and phenomenological design approaches.

Spatial Strategies and Ground Relations: Students investigated the dialogue between housing units, the ground plane, and the island context, aiming to balance public-private thresholds, modular flexibility, and contextual adaptation.

This structured phase was critical for consolidating the conceptual foundations established through the workshops into tangible spatial strategies. It enabled students to critically question and refine their design decisions through iterative testing of forms, materials, and environmental interactions.

5.5. Selected Student Works

As part of the evaluation process, selected student projects were analyzed to demonstrate how experiential learning, material exploration, and tectonic narratives were translated into tangible architectural outputs. These works showcase the diverse ways in which students engaged with the phenomenological and contextual dynamics of the project site, responding to both environmental and social dimensions.

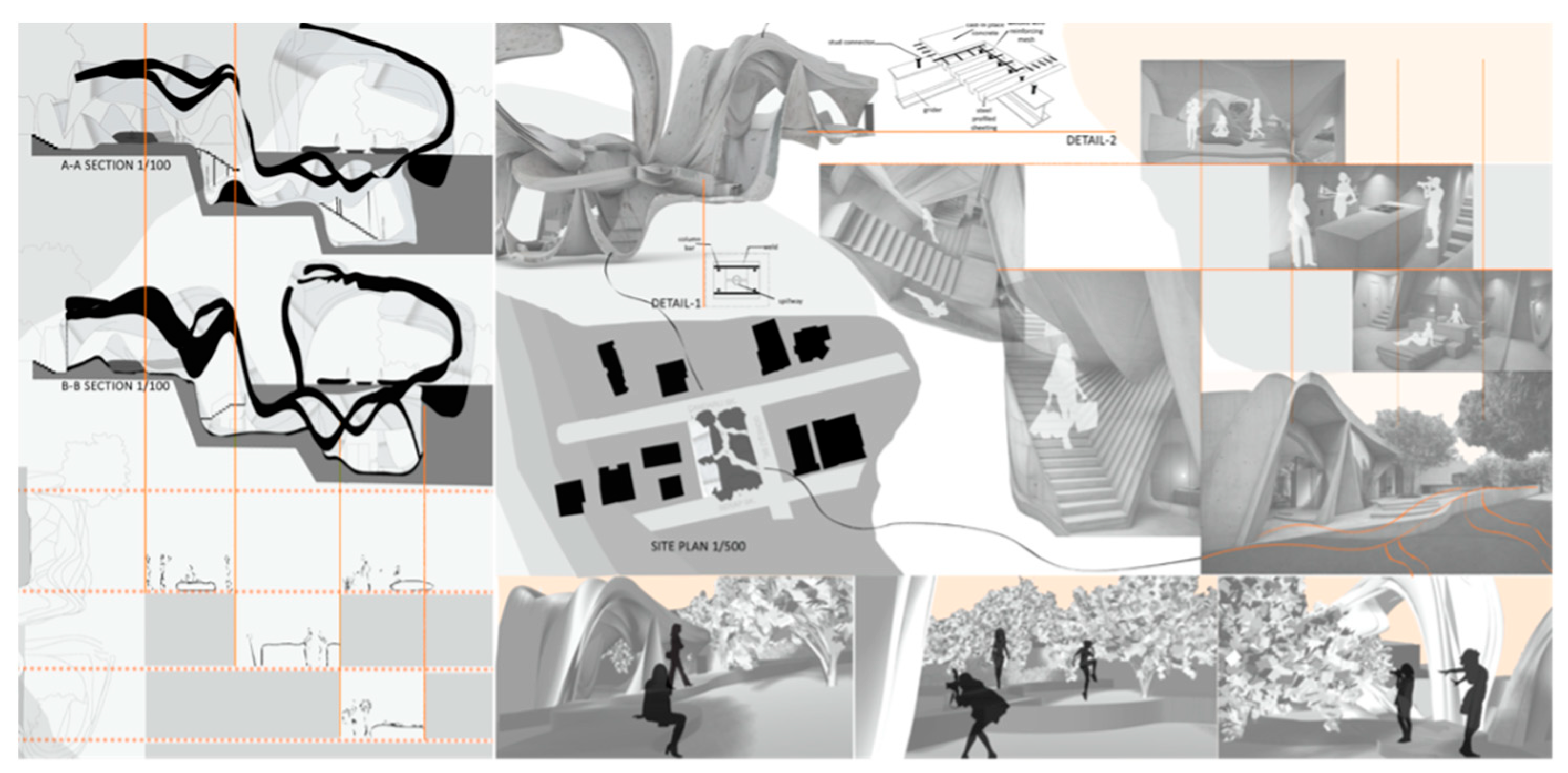

Student Work 1—“Folds Extending to the Earth” [

Figure 11]

Concept: Inspired by natural folds and layering, integrating organic forms with spatial experience.

Function & Form: Creates a semi-enclosed reading space balancing openness and privacy.

Material & Construction: Uses natural fiber, compressed materials, and layering techniques.

Spatial Interaction: Encourages tactile engagement and a sense of belonging to the earth.

Student 5—“Tessellated Spatial Envelope with Adaptive Logic” [

Figure 12].

Concept: Investigates how spatial boundaries can be redefined through geometric tessellation and modular repetition, allowing traditionally rigid enclosures to become dynamic and environmentally responsive.

Function & Form: Develops adaptable spatial configurations by organizing modular components within a repeating geometric logic, enabling transformation in response to user needs and movement.

Material & Construction: Integrates flexible joints, lightweight modules, and smart materials that react to environmental inputs and enable partial reconfiguration of the structure.

Spatial Interaction: Facilitates user-driven adaptability by supporting evolving boundary conditions and customized spatial experiences within a patterned structural framework.

Student 7—“Shell-Inspired Living” [

Figure 13]

Concept: Inspired by organic, shell-like forms, this project aims to create intimate and fluid spaces that blend with natural surroundings.

Function & Form: Spaces are shaped to adapt to the daily rhythms of the residents, including a workshop, living areas, and a garden. The design prioritizes natural light and ventilation.

Material & Construction: Uses lightweight, organic forms with smooth surfaces that mimic the texture and feel of seashells, combining natural aesthetics with functionality.

Spatial Interaction: The design promotes social interaction in flexible, open spaces while maintaining privacy and comfort for individual activities.

Concept: Organic, flowing forms create a seamless connection with the environment.

Function & Form: Curved spaces provide dynamic, flexible areas that blend with the site.

Material & Construction: Concrete and steel are used with a focus on structural integrity.

Spatial Interaction: Open and semi-open spaces foster movement and interaction.

In addition to the detailed studies discussed in the main text, several additional student projects examined complementary dimensions of tectonic design thinking. These projects collectively enhance the broader discourse on phenomenological design approaches in architecture. Summaries and visual documentation of these additional projects are provided in the

Supplementary Materials (see Figures S1–S4).

5.6. Jury Process and Project Refinement

In the final phase, students presented their projects to a jury comprising two studio instructors and three external jurors from various disciplinary backgrounds, ensuring a diverse range of critical insights. This iterative critique-feedback cycle was essential for enhancing both the theoretical depth and practical quality of the projects, specifically emphasizing:

The feedback received during the juries prompted continuous refinement of student projects. Housing scenarios, spatial configurations of housing units, and interactions between the island and housing developments were critically reassessed and adjusted according to the jurors’ suggestions. Students intensively refined their modules, housing typologies, prototypes, and spatial strategies, consolidating initial conceptual ideas into detailed design solutions. This process strengthened the coherence between user needs, site context, and architectural expression.

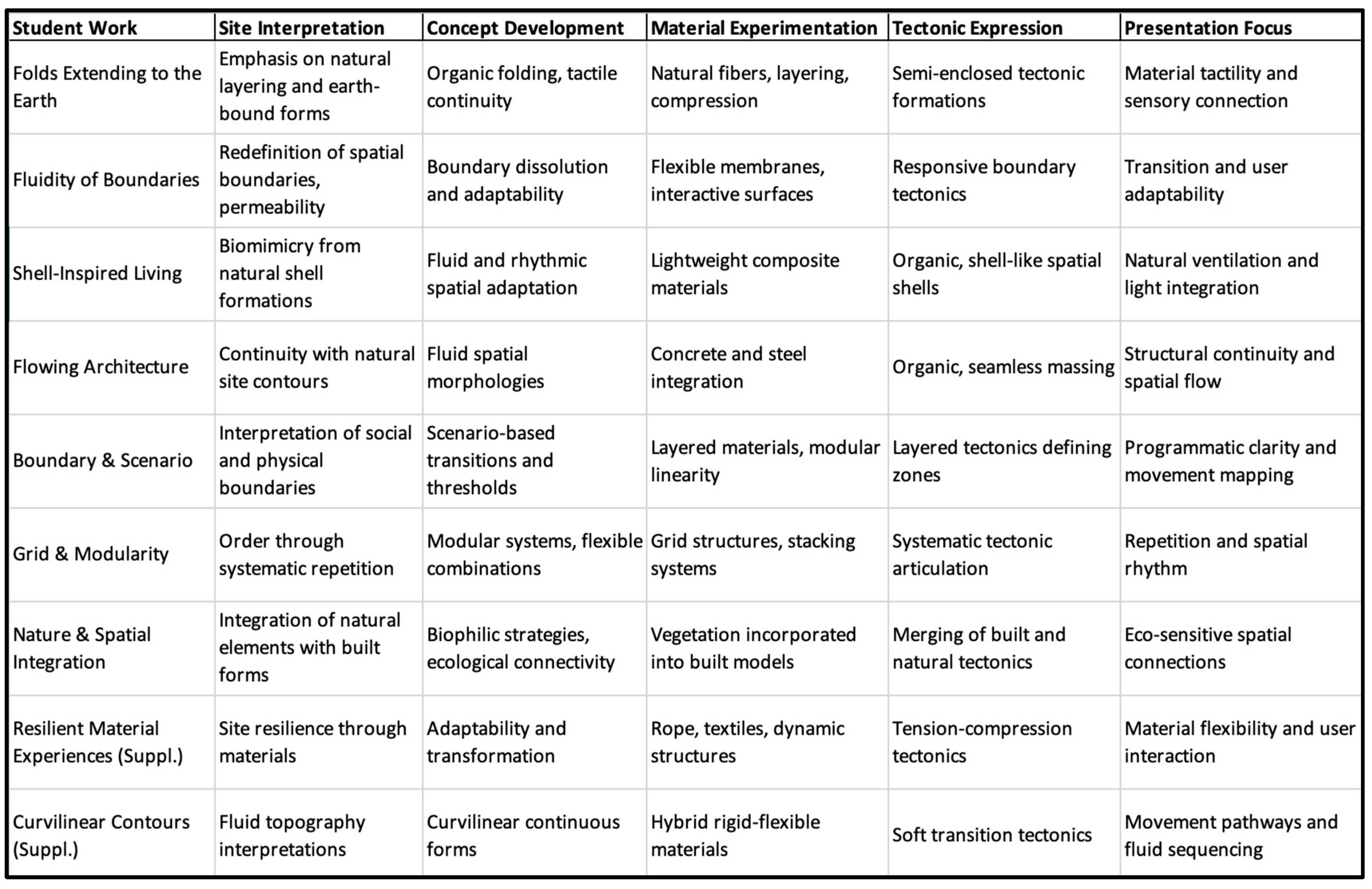

These evaluation criteria and refinement processes were structured systematically through an analytical framework, as outlined in

Figure 15.

Figure 15 outlines the criteria used to systematically evaluate student projects, detailing how various aspects—site interpretation, conceptual development, material experimentation, tectonic clarity, and presentation quality—were integrated to facilitate comprehensive assessment and refinement.

6. Discussion and Evaluation

The architectural design studio’s recent productions are conceived as part of an ongoing creation–production–feedback cycle, a dynamic process that may not culminate in a singular conclusion but evolves over time. Rather than focusing solely on final outcomes, the studio emphasizes the significance of the design journey itself, valuing the iterative experiences and productions generated throughout the 14-week studio process.

In this context, the primary aim was not to categorize students based on success or failure through conventional grading systems, but to guide them through completing the design process aligned with specific criteria. Students were encouraged to actively engage with material, contextual, and tectonic frameworks, developing a coherent architectural expression rather than solely producing finalized outcomes. The studio sought to foster an environment where individual interpretations, critical reflections, and process-oriented thinking were prioritized over rigid assessments.

The main objectives of the architectural design studio were to cultivate a holistic understanding of architectural dynamics, to foster critical and creative thinking, and to bridge the gap between theoretical concepts and design practice. In this framework, innovation refers to the introduction of new strategies, methods, and approaches within the studio process, while creativity is understood as the students’ ability to generate unique and original design outputs based on these innovative explorations. Within this context, students were encouraged to question whether traditional studio approaches remain compatible with the lifestyles, priorities, and values of new generations.

The studio’s focus on tectonics and housing served as a critical driver for the students’ design processes. By exploring the material and structural logic inherent in tectonic thinking, students reimagined housing typologies that respond flexibly to changing social needs and environmental conditions. The integration of tectonic language into architectural education allowed for a deeper material engagement and encouraged designs that were more responsive to site, atmosphere, and human experience.

Personal experiences, memories, and notions of belonging played an instrumental role in shaping students’ spatial interpretations. The students’ recollections of neighborhoods, domestic spaces, and collective environments informed their conceptual development and deepened the emotional resonance of their designs. This phenomenological approach highlighted how lived experiences could act as a crucial mediator between architectural form and social meaning.

In addition, the studio critically addressed how different housing scenarios can be articulated through tectonic expressions. Students explored how tectonic strategies—such as layering, folding, material transitions, and modularity—could give tangible form to diverse ways of living, proposing innovative spatial configurations that accommodate evolving lifestyles.

Throughout the studio process, students provided reflective feedback emphasizing how phenomenological explorations, material experimentation, and contextual analysis enhanced their spatial awareness and deepened their design thinking capacities. Particularly, they found the transition from abstract, conceptual approaches in the first-year studio to more material- and context-driven explorations in the second-year housing project to be enriching and formative for their architectural development.

Looking forward, the studio encouraged students to reflect on how architectural design education must adapt to future societal shifts. Students discussed the need for more flexible, resilient, and contextually aware educational models that prepare architects to engage with complex urban, ecological, and technological challenges. This critical awareness is intended to be further developed in later stages of their education, particularly in the fourth-year Building Construction Project course, where students will confront the realities of material execution and technical detailing, evaluating how initial design intentions are preserved or transformed during the building process.

This study contributes to the design process in architecture studios at both academic and practical levels by providing material experience and sensory awareness.