Abstract

As sustainability becomes an essential approach in the USA hospitality sector, green certifications like Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) are increasingly adopted by hotel developers. However, the extent to which different LEED certification levels influence guest satisfaction remains unclear. This study investigates how the LEED certification level interacts with the relationship between a hotel’s sustainability performance and guest satisfaction in the United States. A mixed-methods approach was used, combining Random Forest Regression and the Process macro on a dataset of LEED-certified USA hotels with normalized guest satisfaction scores. The Random Forest model identified Energy and Atmosphere (EA) and Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ) as the most influential LEED categories in predicting satisfaction. Additionally, the results reveal that the positive effect of sustainability on satisfaction is strongest at the lower LEED levels (Certified and Silver), but shows diminishing returns at higher levels (Gold and Platinum), suggesting that an increased sustainability performance does not uniformly improve guest experience. These findings support all three hypotheses and offer practical insights for hotel developers, operators, and certification bodies seeking to align sustainability strategies with guest expectations.

1. Introduction

The hospitality sector significantly contributes to environmental impacts through energy consumption, water use, and waste generation [1,2]. As awareness of these environmental costs grows, the industry has seen a marked shift toward adopting sustainable practices, including energy efficiency, green procurement, and eco-labeling [3]. In particular, green building certifications such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) have become prominent tools for signaling environmental responsibility and operational excellence (USGBC, 2023) [4]. Hotels adopting LEED are not only aiming for an improved environmental performance but increasingly leverage sustainability as a competitive strategy in attracting environmentally conscious guests [5,6]. Therefore, the effectiveness of these measures must also be evaluated through the lens of guest satisfaction, which is the primary indicator of success in service-oriented environments such as hotels.

The USA hotel industry is a highly competitive and guest-driven market, where guest satisfaction is shaped by a constellation of service and experience attributes, including cleanliness, service quality, staff responsiveness, location, value for money, and increasingly, digital and environmental engagement [7,8]. These factors are critical not only for immediate guest experience but also for influencing online ratings, customer loyalty, and financial performance [7,9]. As environmental awareness grows among travelers, there is increasing demand for eco-conscious accommodations that do not compromise on comfort or service [10,11]. In response, many hotels are turning to green building certifications like LEED as a way to operationalize sustainability and signal their commitment to environmental values.

However, LEED’s impact extends beyond backend efficiencies or marketing appeal. It encompasses features that directly influence guest comfort and well-being, such as indoor air quality, thermal comfort, acoustic control, and natural lighting [12]. These elements closely align with traditional satisfaction drivers and have the potential to reinforce the overall guest experience when effectively implemented. For example, LEED-certified hotels may improve their perceived service quality by offering quieter, cleaner, and better-ventilated rooms, which can influence how guests evaluate their overall stay. When hotels communicate these benefits, LEED becomes not just a green badge but a value proposition that enhances both satisfaction and loyalty [5,6].

Despite this strategic alignment, there is a lack of empirical research examining whether different levels of LEED certification, ranging from Certified to Platinum, actually produce differentiated satisfaction outcomes. Most studies focus on the binary distinction of green vs. non-green, without addressing the gradients of sustainability performance that LEED levels represent. This gap is particularly important in the USA, where guests are sensitive to value perception and comfort, and where LEED adoption is rising but uneven. The current study addresses this gap by examining whether and how the LEED certification level moderates the relationship between sustainability performance and guest satisfaction, with a focus on USA hotel properties.

To guide this investigation, the following hypotheses, focused on the relationship between LEED scores, certification levels, and guest satisfaction, were formulated:

Hypotheses 1.

LEED-certified hotels with higher overall sustainability scores will report higher levels of guest satisfaction.

Hypotheses 2.

The positive relationship between LEED score and guest satisfaction will be moderated by certification level, with diminishing effects at higher tiers (e.g., Gold or Platinum).

Hypotheses 3.

The predictive influence of the Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ) and Energy and Atmosphere (EA) credit categories on guest satisfaction will vary across LEED certification levels.

These hypotheses are tested using a combination of process modeling and machine learning techniques, described in detail in Section 3. This study examines how the overall LEED score and key sustainability categories influence hotel guest satisfaction and whether this relationship varies across certification levels (Certified, Silver, Gold, Platinum). The findings offer practical guidance for hotel developers and insight into evolving green certification systems.

The value of this research lies in its ability to inform hotel developers, policymakers, and sustainability advocates on how to optimize green building practices. Understanding the role of the certification level in guest satisfaction enables decision-makers to refine sustainability strategies, ensuring that investments in green building certifications yield maximum benefits for both the environment and hotel stakeholders. By addressing these gaps, this research makes a significant contribution to the body of knowledge on sustainable hospitality management, green building certifications, and customer satisfaction. The findings will not only enhance academic discourse but also offer practical insights for the hotel industry to better align sustainability initiatives with guest expectations, ultimately fostering a more effective and impactful approach to sustainable hotel design, construction, and operations.

2. Literature Review

The relationship between sustainability and occupant satisfaction has been extensively studied across residential and commercial settings. Guo et al. [13] employed a natural language processing (NLP)-based approach to analyze social media reviews from 232 LEED-certified and 129 non-LEED-certified apartment buildings, revealing marginal satisfaction improvements in certified buildings, particularly concerning lighting. However, disparities in satisfaction levels diminished when rent and property values were accounted for. Goodarzi and Berghorn [14,15,16] expanded upon these findings by developing a post-occupancy evaluation model, demonstrating that sustainable design features significantly enhance occupant experience and overall satisfaction in multifamily residential complexes. These prior studies offer foundational insights into how sustainability metrics translate into user satisfaction.

Further research by Wang et al. [17] examined the relationship between building performance and resident well-being, highlighting that energy-efficient and environmentally conscious designs positively impact occupant satisfaction when coupled with effective system management and user engagement. Similarly, Liu et al. [18] compared satisfaction levels in Chinese Green Building Three-Star-certified and non-certified office buildings, reporting higher satisfaction levels in certified buildings, particularly concerning air quality, humidity, and lighting. These studies suggest that while certification correlates with improved building performance, the degree of impact varies based on contextual and operational factors.

2.1. Sustainability and Satisfaction in Hotels

Research has demonstrated that sustainability influences both operational standards and client expectations in the hospitality sector. Prud’homme et al. [19] found that hotels’ sustainable development methods not only solve environmental challenges but also have a major impact on consumer satisfaction. By surveying 473 guests at eleven hotels in Canada, they found that sustainable elements like energy and water efficiency help to improve guest perceptions, perhaps leading to repeat visits and stronger loyalty. This shows that as people grow more environmentally concerned, they choose hotels that promote sustainable operations. A study by Abulaali et al. [20] explored the effects of several IEQ parameters on guests’ comfort and satisfaction in hotels using a systematic review approach. Their study showed a high connection between indoor environmental quality parameters and visitor happiness in hotels. They indicated that indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting, scenes, acoustic comfort, building design, interior design, and indoor plants are all important aspects of IEQ and have a significant impact on guests’ comfort and overall experience. However, external factors such as temperature and humidity were also found to influence thermal comfort, which directly affects visitors’ experiences.

Moliner et al. [21] investigated how customers’ views of environmental standards in tourist accommodation affect their overall satisfaction and experiences. Their study of 412 Spanish tourists indicated that environmental sustainability positively impacts customer satisfaction by improving the overall consumer experience. Zhang et al. [22] analyzed 543,213 IEQ-related reviews from 1397 hotels on Booking.com and found that LEED-certified hotels improve visitor satisfaction by emphasizing factors such as clean air, low noise, and temperature management. Similarly, Ma et al. [23] used text-mining techniques to analyze over 1.2 million Booking.com reviews, finding that air quality and noise control are critical factors influencing guest satisfaction.

Floricic [24] examined the role of sustainability in hospitality management, particularly among younger travelers. This study found that while over 90% of respondents valued sustainability in hotels, only 52.9% were willing to pay extra for eco-friendly accommodation, highlighting the gap between awareness and purchasing behavior. Chi et al. [25] found that green certifications positively influence booking decisions and consumer trust. Xue et al. [26] reinforced this by demonstrating that guests prefer hotels with visible sustainability initiatives, such as renewable energy use and reduced plastic consumption. Peiro-Signes et al. [27] analyzed the impact of the ISO 14001 [28] environmental certification on hotel ratings, showing that certified hotels received higher ratings, particularly in service and comfort categories. Gerdt et al. [29] found that while sustainability measures enhance guest satisfaction, their effectiveness depends on hotel classification and guest expectations. Berezan et al. [6] investigated how sustainable hotel practices influence satisfaction across different nationalities, demonstrating that while green practices generally improve guest experiences, their perceived importance varies by cultural background, necessitating tailored sustainability strategies.

2.2. LEED and Drivers of Satisfaction

Guest satisfaction in the hospitality sector is typically influenced by tangible and intangible service attributes such as cleanliness, room comfort, staff responsiveness, location, and perceived value [8,30]. With growing environmental consciousness, an emerging body of research explores how green attributes, such as energy-efficient lighting, indoor air quality, natural materials, and noise control, can also enhance the guest experience [10,23]. LEED-certified hotels are uniquely positioned to leverage this trend, as the certification encompasses criteria that overlap with key satisfaction drivers, particularly in the Indoor Environmental Quality and Energy and Atmosphere categories. These features can support wellness-focused stays, quieter room environments, improved lighting, and thermal comfort, enhancing both guest well-being and environmental impact.

Moreover, by explicitly communicating the benefits of LEED-related features (e.g., clean air, natural daylighting, waste reduction), hotels can reinforce their commitment to guest-centered sustainability. Studies have shown that when guests are aware of a hotel’s environmental practices, they are more likely to report higher satisfaction, trust, and return intentions [3,6]. Therefore, LEED certification, when aligned with traditional service dimensions, has the potential to enhance both perceived service quality and environmental value.

2.3. Research Gap and Contribution of This Study

In the context of green hotels, several studies have shown that environmental initiatives positively influence guest attitudes, provided these initiatives do not compromise comfort or convenience [3,31]. USA-based surveys have also indicated that a growing share of hotel guests prefer properties with visible sustainability practices [32], and that a green image can drive brand preference [33]. Yet, few studies have explored how graded certification systems like LEED influence guest satisfaction beyond the binary “green/not-green” distinction and the moderation effect of the level of sustainability remains underexplored.

This lack of nuance is particularly notable in the USA market, where LEED is the dominant green building rating system (USGBC, 2023) [4], and where hotels often use certification in marketing as a signal of operational excellence. However, little is known about whether higher certification levels yield proportionally higher satisfaction. The current study builds on this gap, using empirical data to assess whether the LEED level acts as a moderator in shaping how sustainability performance translates into perceived guest value.

Additionally, past research has examined guest satisfaction largely through either qualitative surveys and review-based sentiment analysis or using one source of data as a measure of user satisfaction. However, there is a need for a more robust, data-driven approach that integrates multiple sources of guest feedback and certification data to identify patterns in sustainability-driven satisfaction.

This study employs machine learning techniques such as Random Forest Regression to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the relationship between certification level and guest satisfaction. In recent years, machine learning models such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), XGBoost, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been applied to predict guest satisfaction or assess sustainable building performance. For instance, Gerdt et al. [29] explored sustainability-driven satisfaction using SVM classifiers, while Zhang et al. [22] employed ANN for modeling the effect of indoor air quality features on satisfaction. Compared to these approaches, Random Forest offers a strong predictive capability with higher interpretability and built-in feature importance rankings, which are particularly useful in explaining model behavior in applied settings such as this study.

While prior work has identified correlations between sustainable practices and guest satisfaction, no study, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has used LEED certification tiers as a moderator or identified diminishing marginal effects at higher levels. Unlike Berezan et al. [6], who explored cultural differences in guest response to green practices, or Gerdt et al. [29], who classified sustainable attributes by perceived importance using eWOM, this study demonstrates a statistically significant nonlinear effect, guest satisfaction increases with sustainability but tapers or reverses beyond a certain LEED threshold.

3. Materials and Methods

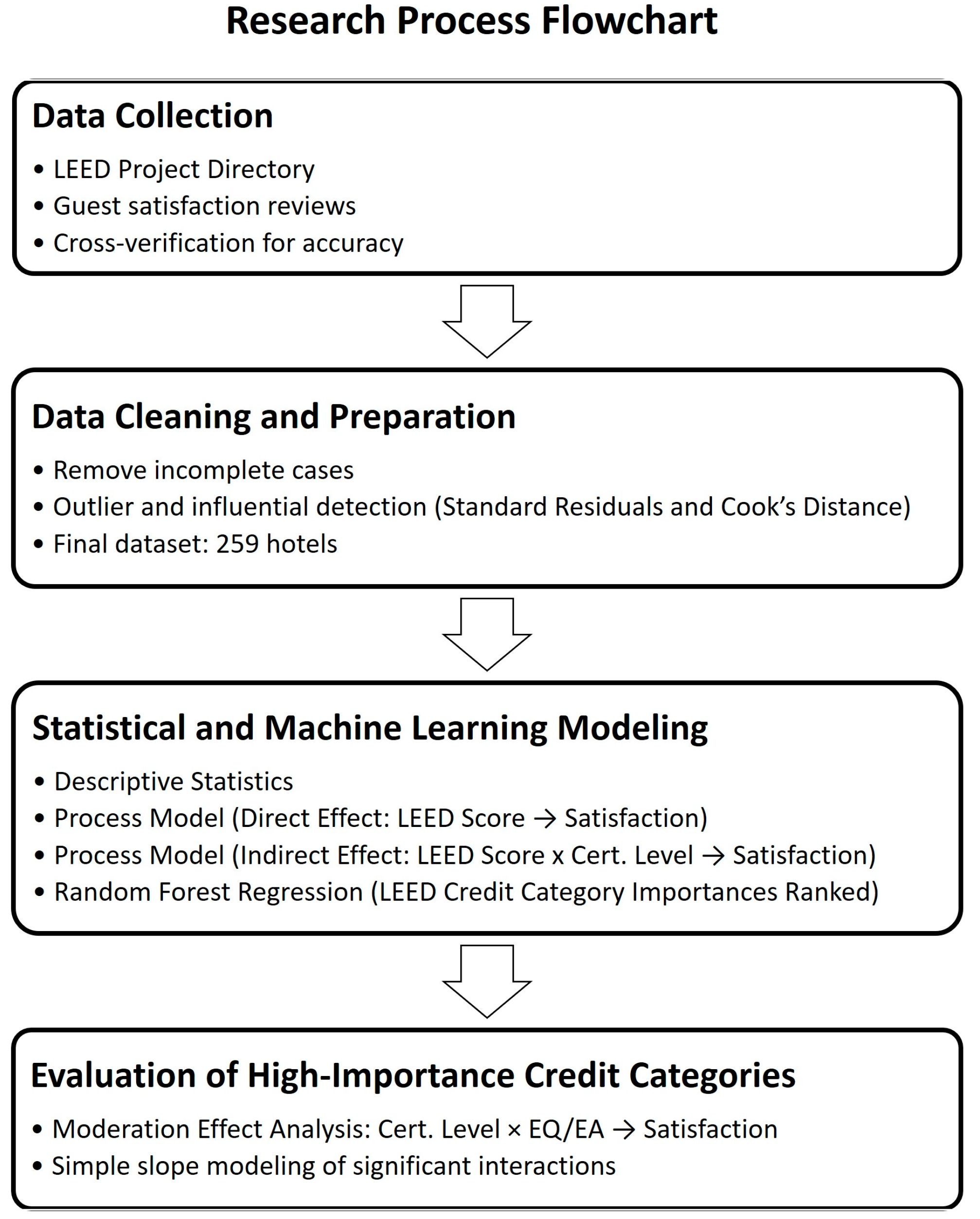

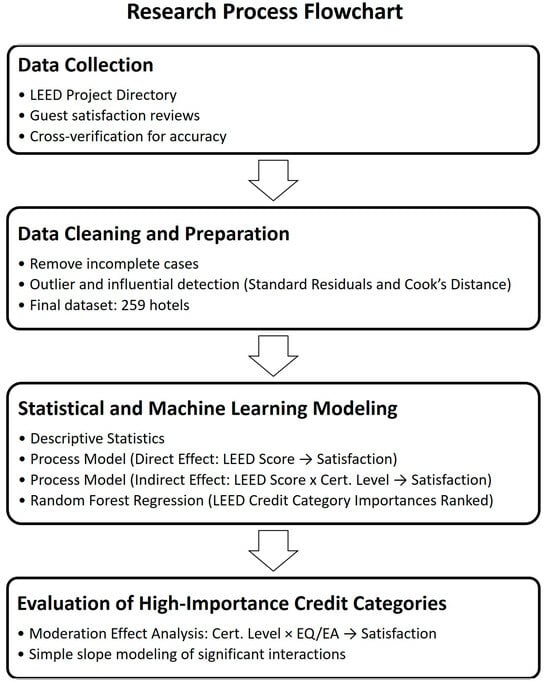

This study utilized a methodical data collection and analysis approach to evaluate the moderation effect of certification level on the relationship between LEED score and satisfaction. The study aims to find out whether the influence of the overall LEED score, as well as the two impactful credit categories, on user satisfaction, varies between the different certification levels of LEED for New Construction version 2009 (LEED NC v2009). Figure 1 shows a methodological flowchart summarizing the stages of the study, from data collection to moderation analysis. Key steps and corresponding results are highlighted.

Figure 1.

Research process flowchart.

This study focuses on hotels certified under LEED NC v2009. Although LEED NC v4 and v4.1 represent the latest versions, LEED NC v2009 remains widely used due to its accessibility, familiarity, and reduced documentation burden. Many project teams continue to choose v2009 because it offers streamlined requirements, more flexible paths to certification, and aligns with established industry practices. As a result, the number of hotel projects certified under v2009 significantly exceeds those under v4 at the time of this research, making it the most practical and generalizable version to study.

By analyzing LEED NC v2009, this study provides insights into sustainable construction strategies that have been adopted at scale across the hospitality sector. Given that many professionals in the building industry are more experienced with this version, the findings are also more likely to resonate with and inform current design and certification practices in the field.

Therefore, LEED v2009 was selected for this study due to its widespread adoption during the period under investigation and the availability of consistent, complete data across projects in the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED Project Directory. Using a single LEED version ensures the comparability of credit structures and point allocations across all analyzed hotels.

3.1. Data Collection and Preparation

Overall LEED scores and the scores achieved in each credit category were collected from the United States Green Building Council’s (USGBC) LEED Project Directory. Detailed project information was collected about all the projects, including certification levels, dates, and locations. Data from each project’s scorecard captured the total LEED points earned, and points allocated to various credit categories such as Sustainable Sites (SS), Water Efficiency (WE), Energy and Atmosphere (EA), Materials and Resources (MR), Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ), Innovation (IN), and Regional Priority (RP).

The satisfaction data was gathered from several travel platforms, including Expedia, Priceline, Kayak, Booking.com, Hotwire, Trip Advisor, Google Review, and the customer reviews on each hotel’s website. To ensure accurate alignment, hotel names, locations, and certification dates from the LEED Project Directory were cross-referenced with listings on travel platforms. Discrepancies were resolved through manual verification using official hotel websites and public directories. If a hotel had insufficient satisfaction data (i.e., fewer than three review platforms with available ratings), it was excluded from the analysis. Therefore, no imputation techniques were used, and only complete and reliable satisfaction data were retained.

The collected satisfaction scores were then normalized and averaged to create a single composite satisfaction score per hotel, which served as the response variable in this study. Guest satisfaction ratings were reported on different scales depending on the platform (e.g., 1–5 stars, 1–10 points, or percentages). To ensure consistency across sources, all satisfaction scores were linearly rescaled to a standard 0–1 range using min–max normalization. For example, a 4.2 rating on a 1–5 scale was converted to 0.84, and an 8.6 on a 1–10 scale was converted to 0.86. After normalization, scores from multiple platforms were averaged to produce a single composite satisfaction score per hotel. This method ensured comparability while preserving the relative satisfaction levels across different review sources.

While min–max normalization was used to rescale guest satisfaction ratings from various platforms to a common 0–1 range, it should be acknowledged that this approach does not fully eliminate differences in rating cultures, demographic tendencies, or platform-specific norms. For example, users on TripAdvisor may exhibit more critical behavior compared to those on Expedia or Booking.com. To partially account for this, this study included platform identifiers as dummy variables in both the linear regression and Random Forest models. This helps control for fixed platform effects in the statistical estimation, though we recognize that more granular corrections, such as hierarchical modeling, could offer further improvements. This limitation is discussed later in the manuscript.

Of the 312 projects certified by 1 March 2025, 278 projects with complete information were analyzed to detect and remove influential and outlier cases using Cook’s Distance and the standardized residual range. Standardized residuals served as the initial diagnostic tool for identifying potential outliers, with any observations exceeding an absolute value of 3 (i.e., standardized residuals > 3 or <−3) flagged for further review [34]. To refine the dataset further and evaluate the influence of individual observations on the overall model, Cook’s Distance was applied as a secondary criterion for detecting influential outliers. Cook’s Distance measures the effect of deleting a given observation and identifies data points that substantially influence the fitted regression model [35]. The threshold for Cook’s Distance was calculated using the following formula:

where n represents the number of observations and k is the number of predictors in the model. This threshold helps identify data points that may exert undue influence on the regression results. For this study, with n = 278 and k = 32, the threshold was calculated as:

Following this data refinement process, 259 projects across four certification levels were retained in the final dataset. Table 1 presents the number of projects that have achieved each certification. The highest number of projects are in the Silver category, accounting for 42.86 percent of the total (N = 111). Second are Certified projects, accounting for 39 percent of the total projects studied (N = 101). Gold-certified projects are the third most frequently achieved certification level, accounting for 15.83 percent of the total (N = 41). Lastly, Platinum projects had the lowest achievement among all certification levels, accounting for only 2.32 percent of the total projects (N = 6).

Table 1.

Frequency of LEED certification level achievement.

3.2. Data Analysis

To analyze the data, this study utilized JASP version 0.19.3 [36], available at JASP. The analysis consisted of four steps. First, descriptive statistics for the data were gathered to understand the number of cases in each credit category and provide some general information about the data. Next, using the PROCESS macro for moderation analysis [37], the direct relationship between sustainability (measured by the overall LEED score) and guest satisfaction was evaluated, and the moderation effect of certification level on the relationship between overall LEED score and satisfaction was then investigated to understand whether this relationship varies between Certified, Silver, Gold, and Platinum levels. The analysis was conducted using JASP, which includes an integrated version of the PROCESS modeling framework.

Next, to understand the importance of each LEED credit category in predicting overall satisfaction and to model the associations and explore the relative importance of these predictors, a Random Forest Regression analysis was conducted. This machine learning algorithm was used to account for the assumptions of the linear regression models and address the modeling limitations in linear regression. Random Forest evaluates the importance of variables based on out-of-bag evaluations of the decision trees in a forest [38]. In this study, rather than assigning equal weight to LEED credit categories, Random Forest Regression was used to determine their actual importance in predicting overall guest satisfaction. This data-driven approach allows the categories to be ranked based on their contribution to prediction accuracy, identifying the most influential variables.

Random Forest was selected over other machine learning techniques due to its ability to handle complex, nonlinear relationships and interactions between variables while maintaining resistance to overfitting. Furthermore, its internal validation via out-of-bag error estimation and feature importance metrics makes it ideal for exploring which sustainability factors most influence satisfaction. While more complex models, such as XGBoost or deep neural networks, could offer incremental gains in prediction, they often require larger datasets and pose challenges towards interpretability, which is critical in the context of informing hotel developers and policymakers.

Even though Random Forest is a well-established ensemble method and not considered state-of-the-art in contemporary machine learning, it remains a robust and interpretable technique, which is particularly useful for evaluating feature importance in nonlinear contexts. In this study, RF is not presented as a novel algorithm but rather as an appropriate tool for identifying the relative predictive power of LEED categories with respect to guest satisfaction. Furthermore, RF handles multicollinearity and interactions effectively, which is especially valuable when LEED categories may correlate or interact. We also recognize that RF has computational overheads and may require more storage than lighter algorithms; however, for our dataset size (~300 observations), these demands were manageable.

Random Forest Modeling Details

The Random Forest (RF) analysis was conducted using JASP software (v0.19.3). To validate model performance and mitigate overfitting, this study employed out-of-bag (OOB) error estimation, an internal cross-validation mechanism of Random Forest, which evaluates prediction error using samples excluded from each bootstrap iteration. The full dataset (n = 259 hotels) was automatically split into training (n = 222), validation (n = 25), and test (n = 12) subsets. The model used 88 trees with 2 features per split, and scale features were enabled. The RF model was trained using out-of-bag estimation, which also served to minimize overfitting and validate performance.

Inputs consisted of seven normalized LEED category scores: EA, EQ, SS, MR, RP, WE, and INN. The target was a min–max-normalized guest satisfaction score. No categorical control variables (e.g., platform or region) were included in this exploratory analysis to isolate the contribution of LEED factors.

The model performance metrics used were as follows: R2 = 0.69; MAPE = 61.58%; RMSE = 0.158; and MSE = 0.025. Feature importance was evaluated using three metrics: mean decrease in accuracy, total increase in node purity, and mean dropout loss based on 50 permutations.

After ranking the LEED credit categories based on their predictive power through Random Forest analysis, the high-importance credit categories that showed the highest contribution to guest satisfaction were entered into another Classical Process Model analysis. This was conducted to understand whether the predictive power of these credit categories on satisfaction changes by the certification level. Finally, the relationships that were shown to be affected by certification level were further evaluated using a Simple Slope Model, a post hoc analysis method for probing interaction effects in moderation analysis [37].

4. Results

4.1. Classical Process Model on the Relationships Between Sustainability and Satisfaction

The classical process model analysis examined the relationship between sustainability (measured by LEED points) and satisfaction and evaluated the moderation effect of certification level on the relationship between sustainability efforts and guest satisfaction in LEED-certified hotels.

The results, presented in Table 2, indicate a moderately strong positive effect of sustainability efforts on guest satisfaction (β = 0.621, 95% CI [0.122, 1.120], p = 0.015), suggesting that each additional LEED point contributes meaningfully to improved satisfaction. However, certification level alone does not have a significant direct effect on satisfaction (β = −0.031, SE = 0.041, p = 0.448), implying that a higher certification level (e.g., Silver, Gold, or Platinum) does not necessarily lead to higher guest satisfaction independently of sustainability efforts.

Table 2.

Moderation effect of certification level on the relationship between LEED score and guest satisfaction.

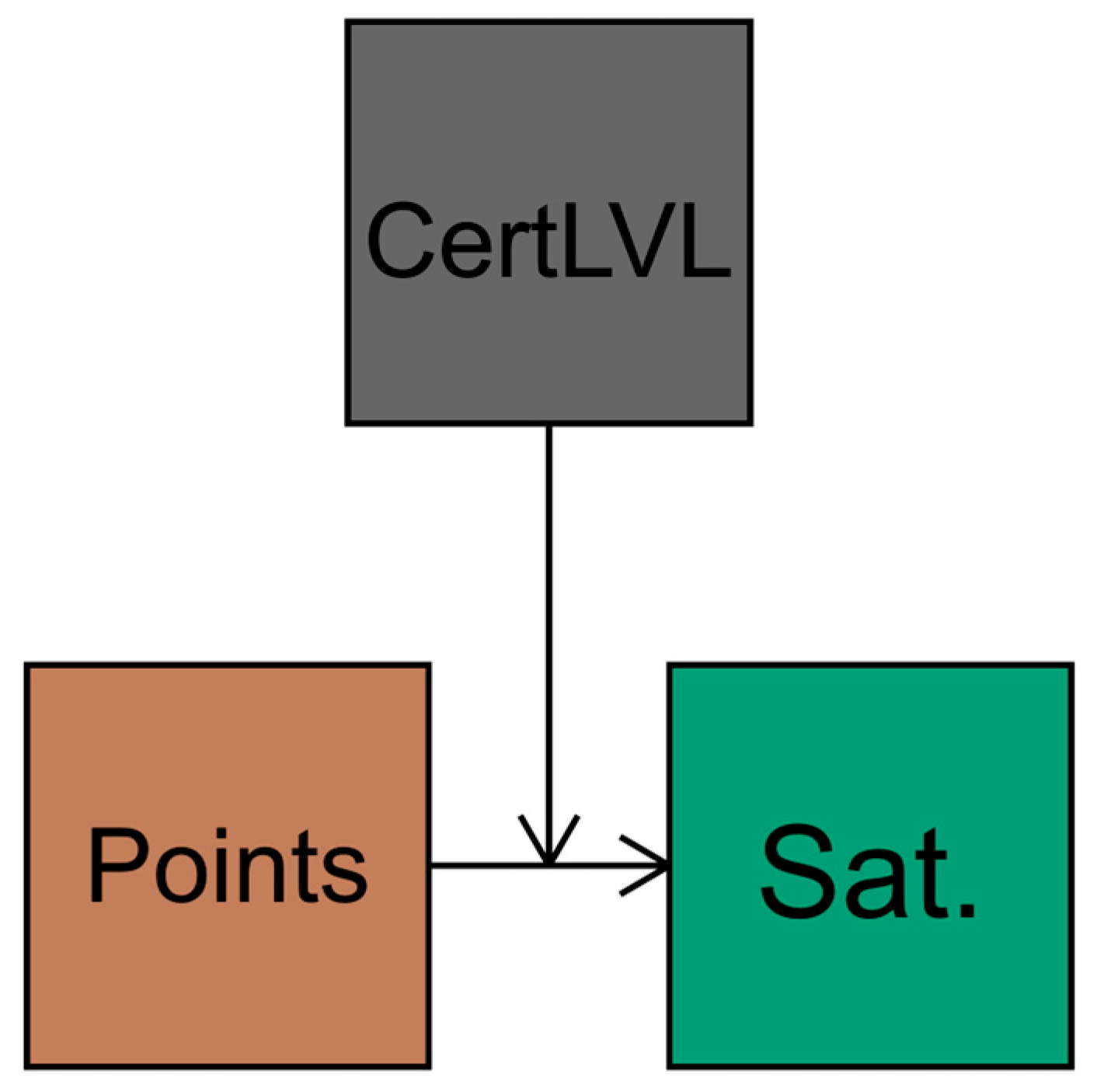

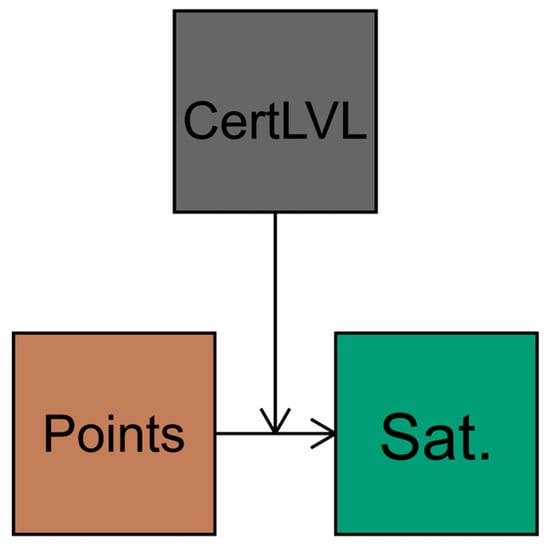

The interaction between sustainability and certification level (β = −0.084, SE = 0.043, p = 0.046) was, however, statistically significant, suggesting a moderating effect of certification level on the relationship between sustainability and satisfaction. The negative coefficient indicates that while sustainability efforts generally increase satisfaction, the effect diminishes as the certification level increases. Figure 2 indicates the moderation model structure, showing the effect of the LEED score on guest satisfaction, moderated by certification level.

Figure 2.

Model structure of the moderation effect.

Although the interaction term’s coefficient is low, suggesting a weak moderation effect, its significance indicates that higher certification levels may not necessarily enhance the positive impact of sustainability efforts on guest satisfaction and, in some cases, could slightly diminish it. Nonetheless, the strong positive association between sustainability and guest satisfaction underscores the need for a deeper examination of the factors contributing to overall sustainability, particularly the LEED NC v2009 credit categories, and their relationship to guest satisfaction. To explore this further, a Random Forest Regression analysis was conducted, using credit categories as predictors and satisfaction as the response variable, to assess the predictive power of each credit category in influencing guest satisfaction in LEED-certified hotels.

4.2. Random Forest Regression

The Random Forest Regression model predicts an output ŷ by averaging the predictions from an ensemble of T individual regression trees. The overall prediction for an observation x is given by:

where (X) represents the prediction of the t-th decision tree for input X, and T is the total number of trees in the forest (88 in this study). Each tree is trained on a bootstrap sample of the training data, and only a random subset of features is considered at each node split.

The RF regression model demonstrated limited predictive accuracy in evaluating green building parameters, as shown by key performance metrics (Table 3). The model achieved a mean squared error (MSE) of 0.025, with a scaled MSE of 0.31, indicating a relatively low prediction error. The root mean squared error (RMSE) was 0.158, and the mean absolute error (MAE) was 0.122, further affirming the model’s accuracy. However, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was notably high at 61.58%, suggesting potential variability in relative prediction errors. Despite this, the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.69, suggesting that the model explains 69% of the variance in the dependent variable, which is a reasonable fit given the complexity of green building performance data. The relatively high MAPE (61.58%) may be attributed to heterogeneity in guest preferences and behaviors across hotels, as well as regional differences in climate, culture, or hotel classification that influence satisfaction in ways not fully captured by LEED credit data. This high error rate may be due to the inherent subjectivity of guest satisfaction ratings, the modest sample size (n = 259), and the absence of hotel-level control variables (e.g., brand, location, room rates). Therefore, model predictions should be interpreted cautiously, and the use of Random Forest in this study is primarily aimed at exploring feature importance, rather than delivering precise forecasts.

Table 3.

Model performance metrics.

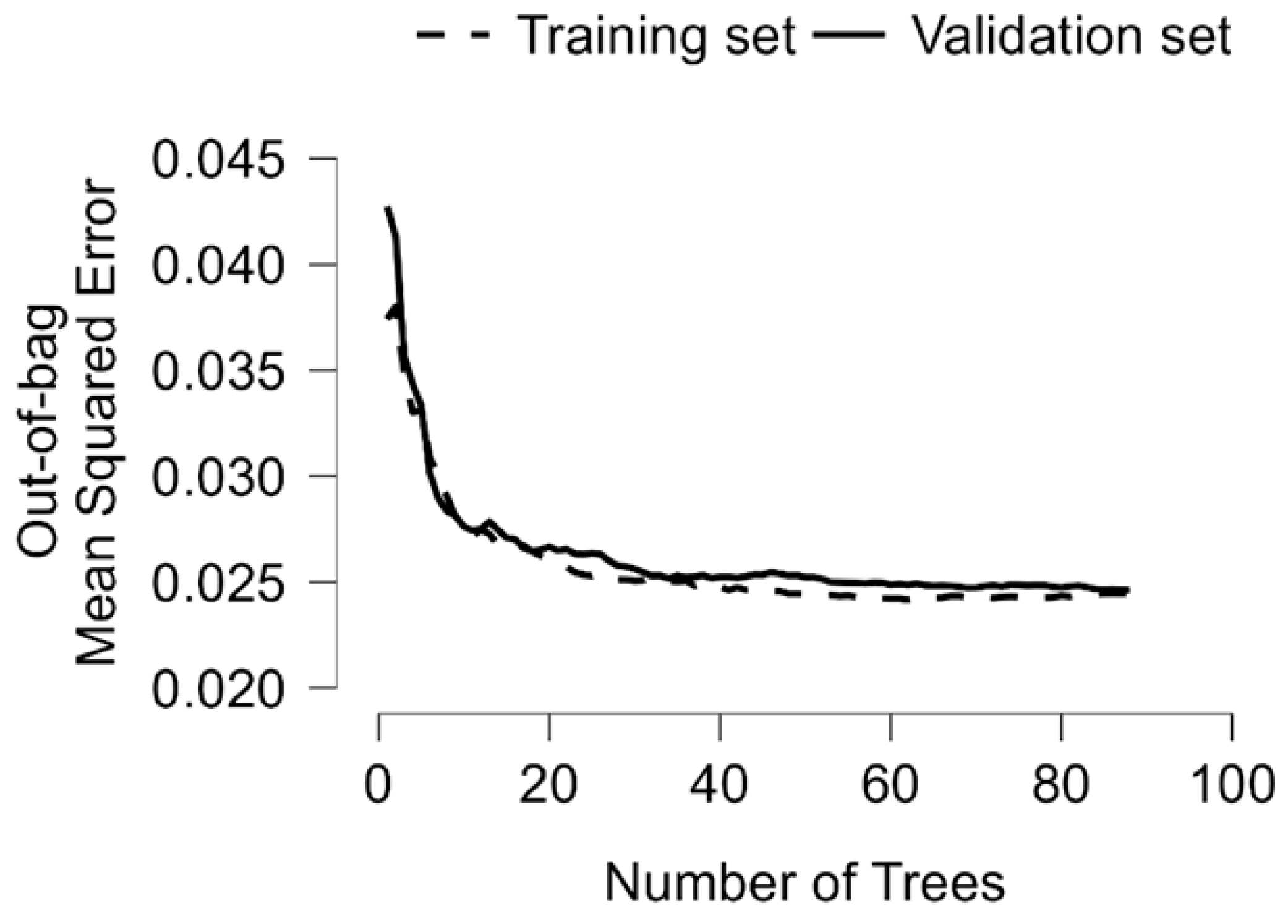

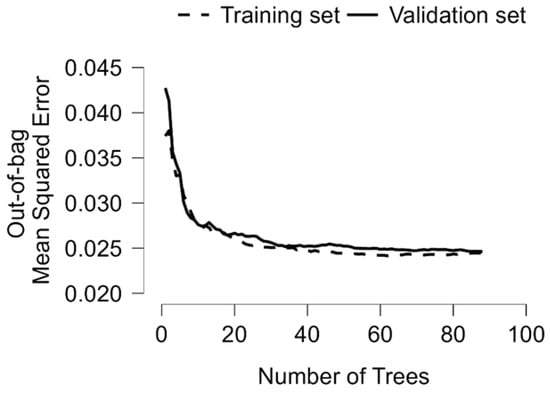

The model configuration, summarized in Table 4, consisted of 88 trees with two features per split. The training dataset included 222 samples, with 25 used for validation and 12 for testing. The validation and test MSE values were consistent at 0.025, reinforcing the model’s generalizability. Additionally, the out-of-bag (OOB) error, optimized during model training, was also 0.025, confirming stable performance across subsets of the data. The OOB mean squared error plot (Figure 3) provides further visual validation of the model’s reliability.

Table 4.

Model summary: Random Forest Regression.

Figure 3.

Out-of-bag mean squared error plot.

The feature importance analysis (Table 5) identified key predictors influencing the model’s performance. The most significant variables based on the mean decrease in accuracy and the total increase in node purity were EQ (0.00290 and 0.432, respectively) and EA (0.00270 and 0.458, respectively), indicating their strong predictive contributions. Other features, such as MR, RP, SS, IN, and WE, had lower importance scores but still played a role in model performance. Notably, mean dropout loss, a measure of variable significance in prediction, was highest for EQ (0.139) and EA (0.136), further validating their relevance in green building assessments.

Table 5.

Feature importance metrics.

Overall, the Random Forest model demonstrated a solid predictive power and stability, with key environmental and structural parameters driving model performance. While the MAPE value suggests potential room for improvement in reducing relative errors, the model’s high R2 and low OOB error indicate strong reliability in predicting green building outcomes.

4.3. Moderation Effect of Certification on Credit Categories and Satisfaction Relationship

The results of the Random Forest Regression analysis showed that the EQ and EA credit categories have the highest predictive power in determining the overall satisfaction of the LEED-certified hotels. Therefore, these two variables were entered into a Classical Process Model to evaluate the moderation effect of certification level on their relationships with overall satisfaction. In other words, it was necessary to understand whether their relationships with overall satisfaction vary by the certification levels (Table 6).

Table 6.

Moderation effect of certification level on the relationship between EQ and EA scores and guest satisfaction.

Since the moderation effect of the certification level on the relationship between the Energy and Atmosphere credit category and satisfaction was significant, this effect was further investigated to understand the relationship between those factors in each certification level. Table 7 shows the results of this analysis.

Table 7.

The relationship between EA score and guest satisfaction across certification levels.

The path coefficients indicate a substantial negative relationship between EA score and satisfaction at the Gold certification level (β = −0.576, 95% CI [−1.033, −0.120], p = 0.013), suggesting that additional EA credits at this level are associated with a decrease in satisfaction. However, this relationship is negative, suggesting that with an increase in the LEED score at this level, the level of satisfaction decreases significantly (β = −0.576, p = 0.013). The interactions between EA and both CertLVL-2 (β = −0.085, p = 0.665, 95% CI: [−0.473, 0.302]) and CertLVL-4 (β = −0.082, p = 0.846, 95% CI: [−0.912, 0.747]) were not statistically significant, indicating limited moderation effects at these levels. These findings underscore the importance of EA in driving satisfaction, particularly at the Gold certification level, while suggesting diminishing returns of EA on satisfaction at higher certification levels.

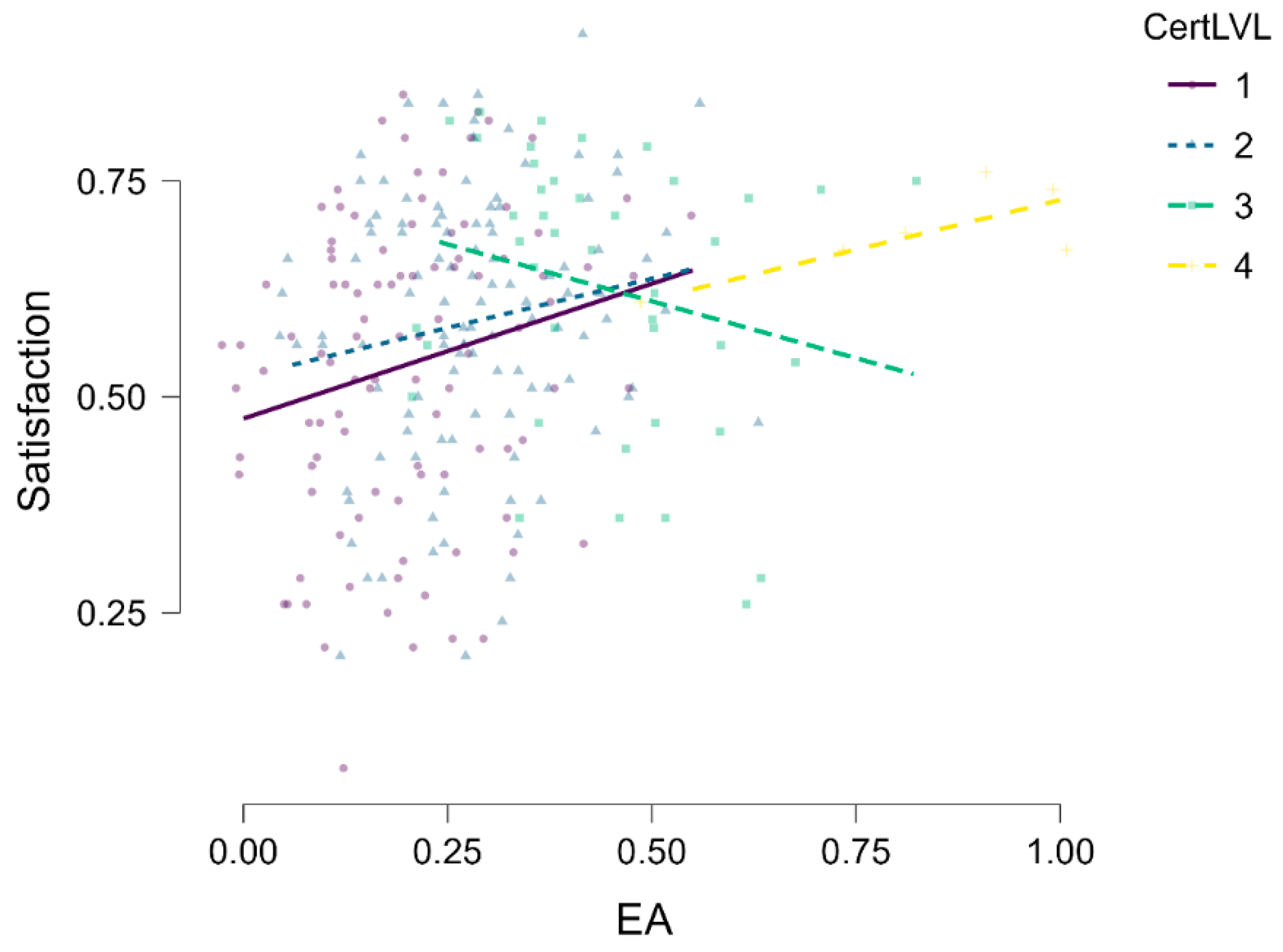

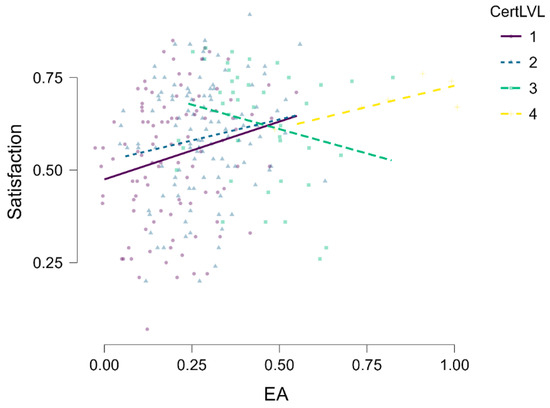

To investigate the nature of this interaction effect, it is important to draw a simple slope model for the moderation effect [39,40]. The simple slope model was developed to visualize the changes in the relationships between the predictor and response variable across certification levels (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Simple slope model: moderation effect of certification level on satisfaction vs. EA.

As shown in Figure 2, the variation in slopes across certification levels illustrates the moderating effect. Level 3, the only level that has a significant interaction term, has a visibly different trend compared to the baseline (Level 1). The slopes for the Silver and Platinum levels show less variation compared to the baseline. This visual evidence supports the statistical finding of diminishing returns, where the impact of LEED scores on satisfaction lessens as certification levels rise. However, this variation from baseline is only significant at the Gold certification level suggesting that only this level has a meaningful variation from the Certified level in terms of the predictive power of the Energy and Atmosphere credit category in predicting overall satisfaction with the studied projects.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to a growing body of literature examining the relationship between green building certifications and user satisfaction, specifically within the hospitality sector. By employing a rigorous statistical approach, this study provides empirical evidence that LEED certification levels exert a moderating effect on the relationship between sustainability efforts and guest satisfaction in hotels. The results reveal a strong positive association between overall LEED points and guest satisfaction, suggesting that sustainability-driven design, construction, and operational practices play a crucial role in enhancing guest experiences. This effect, quantified by a standardized coefficient of 0.621 with a 95% confidence interval [0.122, 1.120], underscores the practical importance of sustainability-related features in shaping the guest experience. However, the significant moderating effect of certification level challenges the assumption that a higher certification level necessarily translates into proportionally greater guest satisfaction.

This study’s findings indicate that the positive impact of sustainability efforts is most pronounced at the lower certification tiers, particularly at the Certified and Silver levels. However, the diminishing returns observed at the Gold and Platinum certification levels imply that once a hotel reaches a certain sustainability threshold, additional investments in green building features may not yield commensurate improvements in guest satisfaction. This trend is particularly evident in the Energy and Atmosphere (EA) credit category, where the moderation analysis reveals a significant negative interaction between EA scores and guest satisfaction at the Gold level. One possible explanation for the drop in satisfaction at the Gold level is that the additional sustainability measures required to move from Silver to Gold are often backend or infrastructure-related upgrades, such as energy management systems, high-efficiency HVAC, or advanced commissioning, which may not be visible or perceptible to guests. Another possible explanation for the diminishing returns observed at higher certification levels is that certain sustainability strategies, such as energy optimization through highly controlled HVAC systems, may inadvertently reduce guest-perceived comfort or autonomy. For instance, automated systems that tightly regulate room temperature, lighting, or airflow may limit guest control, leading to subtle dissatisfaction. However, it is important to note that this interpretation is hypothetical; we did not collect direct evidence of guest discomfort related to specific features. Future studies using guest survey responses or review text analysis could explore this hypothesis in greater depth. Additionally, the cost of achieving Gold-level certification may be reflected in higher room rates, which could raise guest expectations without a corresponding improvement in perceived service or comfort, leading to lower satisfaction.

These findings suggest that beyond a certain point, incremental investments in sustainability may not align with guest expectations, potentially leading to unintended negative consequences. The moderation analysis, visualized through the simple slope models, indicates that hotels at the Certified level exhibit a steeper positive trajectory in satisfaction relative to incremental LEED score gains, compared to the Silver, Gold, and Platinum categories. Specifically, while hotels at the Certified level demonstrate a steep, positive response to incremental improvements in sustainability, as reflected in guest satisfaction, the benefits taper off at higher certification levels. This counterintuitive result may be due to factors such as increased operational complexities or elevated costs that are passed on to guests, thereby altering the perceived value proposition.

This pattern of diminishing returns goes beyond prior observations (e.g., Gerdt et al., [29]), which identified certain sustainability features as “dissatisfiers,” but did not quantify how these effects vary by certification level. The use of interaction modeling in this study confirms that additional EA credits at the Gold level may reduce guest satisfaction, a finding not previously documented in the literature.

The Random Forest Regression analysis further elucidated these dynamics by highlighting Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ) and Energy and Atmosphere (EA) as the most significant predictors of guest satisfaction. These findings are consistent with Zhang et al. [22], who analyzed over half a million hotel reviews and found that air quality and thermal comfort significantly affect satisfaction, and Ma et al. [23], who emphasized energy efficiency and noise control as key factors in guest experience [22,23]. However, the process modeling results add nuance to the literature by suggesting that the relationship between these sustainability metrics and guest satisfaction is nonlinear and subject to diminishing returns at higher levels of certification. Such findings challenge the prevailing assumption that more is always better in sustainable design and call for a more balanced approach that aligns technological enhancements with guest perceptions and economic feasibility. It is also important to recognize that the observed diminishing returns may not apply uniformly across all guest segments. For example, wellness travelers, eco-tourists, or corporate clients with sustainability mandates may perceive high-level sustainability features, such as enhanced air filtration, biophilic design, or on-site renewable energy, as value-adding amenities that enhance their overall experience. For these niche markets, the environmental performance and visible alignment with personal or organizational values may outweigh potential trade-offs in cost or operational flexibility. Future studies could explore satisfaction outcomes among specific traveler types to assess whether certain segments derive greater benefit from Platinum-level or wellness-focused certifications.

This suggests that the relationship between sustainability and user satisfaction is more complex than previously assumed and that the efficacy of sustainability investments may be contingent on the contextual balance between enhanced environmental features and the inherent expectations of guests. These findings build on earlier work by Goodarzi and Berghorn [14,15,16], which emphasized the importance of aligning LEED-ND evaluation criteria with user-centered outcomes in community-level projects.

Contextualizing these findings within the broader literature reveals a significant departure from earlier studies that predominantly focused on binary comparisons between certified and non-certified hotels. While previous work (e.g., [12,13]) generally reported linear improvements in satisfaction with increased sustainability, this study demonstrates that the efficacy of green building practices is moderated by the certification level. This suggests that guest satisfaction may reach an optimal threshold beyond which further investments do not yield proportionate returns. As such, hotel developers and policymakers must carefully consider the cost–benefit trade-offs of pursuing higher certification levels, ensuring that sustainability enhancements do not exceed the actual preferences and expectations of their clients.

The observed diminishing returns effect contrasts with earlier work that generally assumed a linear relationship between sustainability and satisfaction. For example, Moliner et al. [21] found that tourists positively associate environmental responsibility with service quality, but they did not account for differences in levels. Similarly, Gerdt et al. [29] reported that sustainability measures enhance guest satisfaction but noted that their effectiveness is contingent on guest expectations and hotel classification. The findings of this study add to this discourse by suggesting that while sustainability remains a key driver of guest satisfaction, its influence is contingent upon both perceptibility and alignment with guest priorities.

Another important contribution of this study is the application of machine learning techniques—in particular, Random Forest Regression—to rank the relative importance of different LEED credit categories. The results confirm that Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ) and Energy and Atmosphere (EA) are the strongest predictors of satisfaction, reinforcing prior findings that guests are particularly sensitive to air quality, noise levels, thermal comfort, and lighting [20]. However, the moderation analysis demonstrates that the relationship between EA and satisfaction weakens as certification levels increase, further supporting the argument that certain sustainability features lose their perceived value at higher certification tiers.

It is also important to consider that non-LEED factors such as service quality, location, or hotel tier could moderate the relationship between sustainability and satisfaction. For example, higher-end hotels may offset energy or water-saving limitations with exceptional service delivery, while climate zones or guest origin may affect comfort expectations. As such, the observed diminishing returns at higher LEED levels may be partially influenced by contextual factors not captured in this study.

5.1. Findings of the Study in the Context of Sustainable Hotels

The evidence presented in this study highlights an important nuance in the design and operation of LEED-certified hotels: while sustainability is a critical factor in guest satisfaction, the way it is perceived and experienced varies depending on the certification level. The results suggest that guests respond positively to visible and functional sustainability features such as improved indoor air quality, enhanced energy efficiency, and better thermal comfort. However, as certification levels increase, additional sustainability measures may become less perceptible to guests, leading to an apparent plateau in satisfaction gains.

One possible explanation for this trend is that at higher certification levels, sustainability investments may prioritize backend infrastructure improvements (e.g., advanced energy management systems, high-performance HVAC systems, renewable energy integration) that, while environmentally beneficial, are not necessarily tangible to hotel guests. In contrast, lower certification levels tend to focus on more perceptible green features such as improved indoor air quality, lighting, water conservation measures, and waste reduction programs—elements that guests are more likely to notice and appreciate.

Additionally, as hotels aim for Gold or Platinum certification, there may be trade-offs that impact guest experience. For instance, aggressive energy conservation measures could lead to overly restrictive climate control settings, while the use of low-flow water fixtures—despite their sustainability benefits—may not always be well received by guests who prioritize comfort over environmental considerations. Furthermore, higher certification levels often require more stringent operational protocols and staff training, which, if not executed seamlessly, could result in service inefficiencies that detract from the overall guest experience.

5.2. Practical Implications

These findings have significant implications for hotel developers, operators, and policymakers seeking to optimize sustainability strategies in the hospitality industry. First, the results suggest that hotel developers should adopt a balanced approach when pursuing LEED certification. Rather than prioritizing the highest possible certification level, they should focus on sustainability features that directly enhance guest experience and comfort. Investments in indoor air quality improvements, noise reduction strategies, and user-friendly energy-efficient technologies are likely to yield the highest returns in terms of guest satisfaction. For example, while LED lighting and occupancy sensors may sufficiently meet both energy and satisfaction goals, more advanced (and expensive) lighting control systems such as circadian lighting or daylight harvesting may be unnecessary unless hotels are targeting Platinum certification or a wellness-focused brand identity. Similarly, heat recovery systems, although useful for energy performance, are unlikely to influence guest perception unless indirectly tied to thermal comfort or air freshness. As such, developers should critically assess the experiential value of each green technology relative to its cost and LEED contribution, and consider rebalancing budgets accordingly.

Second, hotel operators should consider how they communicate sustainability initiatives to guests. Given that many high-level sustainability measures (e.g., energy-efficient building envelopes and water reclamation systems) are not immediately visible, hotels should engage in proactive sustainability branding and education efforts to ensure that guests recognize and appreciate these features. Strategies such as in-room sustainability messaging, interactive green building tours, and digital dashboards displaying real-time energy savings could help bridge the gap between sustainability efforts and guest perception.

Finally, in the context of LEED-certified hotels, these insights invite a re-evaluation of green building strategies. They imply that while initial investments in sustainability can yield substantial improvements in guest satisfaction, further escalation of the certification level might not only fail to produce additional benefits but could potentially introduce diminishing returns. Such an outcome could be attributed to factors such as increased construction and operational costs, over-engineering of sustainability features, or a misalignment between what is technologically advanced and what is perceptibly valuable to guests. Consequently, policymakers and certification bodies should take these findings into account when refining green building rating systems. The results suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach to sustainability certification may not be optimal. Future iterations of the LEED system could introduce additional metrics that assess guest perception and user experience to ensure that sustainability measures align with occupant expectations. Policymakers may also consider incentivizing features that have both environmental benefits and tangible guest comfort improvements, such as enhanced natural lighting, superior air filtration, and biophilic design elements.

Based on these findings, hotel developers should consider the following actionable strategies:

- Focus on perceptible features that directly enhance guest comfort, such as indoor air quality, thermal regulation, and noise control, which were shown to have the strongest association with satisfaction.

- Avoid over-investing in certification levels beyond the point of diminishing returns (e.g., Gold and Platinum), unless guest-facing benefits are communicated or operational goals justify the upgrade.

- Communicate sustainability measures effectively, especially those not directly visible to guests (e.g., energy management systems or water reuse). Tools like in-room infographics, mobile apps, or digital dashboards can help align perception with sustainability investments.

Beyond hotel-level strategies, these findings have implications for green building rating systems and policy development. LEED and similar frameworks may consider incorporating post-occupancy user satisfaction data or perception-based metrics to validate the experiential value of sustainability credits. Credit weighting could also be revisited to prioritize categories with demonstrated influence on guest comfort, such as indoor environmental quality. Policymakers may further support this alignment by offering incentives for hotels that achieve both high sustainability performance and positive user experience benchmarks.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence that sustainability efforts in LEED-certified hotels positively influence guest satisfaction, but the extent of this impact is moderated by certification level. The results indicate that while lower certification levels (Certified and Silver) exhibit strong positive relationships between sustainability efforts and guest satisfaction, higher certification levels (Gold and Platinum) show diminishing returns. In particular, the Energy and Atmosphere credit category demonstrates a significant negative moderation effect at the Gold level, suggesting that beyond a certain threshold, sustainability investments may not yield proportional guest satisfaction gains.

These findings challenge the assumption that higher certification levels inherently lead to better guest experiences, highlighting the need for a more strategic and experience-driven approach to green building design. The study underscores the importance of investing in sustainability features that are both environmentally effective and perceptible to guests, such as indoor air quality improvements, noise reduction measures, and user-friendly energy-efficient technologies. These results underscore the need for a balanced and context-specific approach to green building design, where the pursuit of higher certification levels is carefully weighed against the practical outcomes in terms of guest satisfaction and operational efficiency. Practical strategies include emphasizing guest-perceptible features, avoiding diminishing returns at higher certification levels, and improving the communication of invisible sustainability efforts to guests. Additionally, the findings provide insight for refining the LEED certification itself, suggesting the need to integrate more user-centric evaluation criteria and reassess the value of certain high-level sustainability features that may not enhance guest satisfaction proportionally.

Although achieving higher levels of LEED certification often requires implementing a broad range of sustainability technologies, not all of them contribute equally to guest satisfaction. This study found that categories such as Materials and Resources (MR) and Innovation in Design (ID) had low predictive importance in the Random Forest model, suggesting they may be less perceptible or valued by guests. In contrast, features tied directly to comfort and usability, including indoor environmental quality (EQ), energy efficiency (EA), and daylighting, were more strongly associated with satisfaction.

Developers may consider focusing investment on technologies that are visible, experiential, and comfort-enhancing, such as demand-controlled ventilation, thermal zoning, and noise-reduction systems, especially in projects where guest satisfaction is a core performance indicator. Conversely, overinvesting in backend systems that are not experienced by the guest may yield diminishing returns in satisfaction, despite contributing to LEED point accumulation.

Despite the robust analytical approach used in this study, several limitations should be acknowledged:

- The sample size for certain certification levels, notably Platinum, was limited, which not only affects statistical power but may also have introduced model bias during the machine learning predictions. The class imbalance may have led to a lower prediction reliability for underrepresented categories.

- The study relied on aggregated guest satisfaction data from multiple online platforms, which, while comprehensive, may introduce variability due to differing rating scales and guest demographics.

- While well-established statistical techniques such as Random Forest Regression were employed to capture complex interactions, the model’s relatively high mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) suggests that while the model may capture general patterns and rank feature importance effectively, it should not be used for precise prediction of guest satisfaction scores. Future studies could improve model performance by incorporating additional variables (e.g., hotel brand, location, price tier) and increasing dataset size to enhance stability.

- While Random Forest is effective for handling nonlinearity and estimating variable importance, it is not considered a novel technique in modern machine learning. Additionally, RF requires large amounts of storage and may underperform with smaller datasets. RF was selected for its interpretability and robustness, but future studies could explore more scalable and optimized algorithms such as XGBoost or LightGBM to validate or extend our findings.

- The Random Forest model was implemented using JASP v0.19.3, which offers a streamlined and user-friendly interface but provides limited flexibility for advanced parameter tuning compared to platforms such as Python or R. While adequate for our study goals, future research might benefit from more advanced platforms for fine-grained control, the inclusion of categorical variables, or model comparison.

- Guest satisfaction data were aggregated from multiple review platforms with distinct rating cultures and user profiles. Although normalization addresses scale differences, it does not fully correct for platform-specific tendencies in guest ratings. While we controlled for these fixed effects by including platform dummy variables in our models, future work should consider more robust correction methods, such as multilevel modeling or platform-specific baselines, to improve accuracy.

- Some explanations offered for the decline in guest satisfaction at higher certification levels, such as reduced comfort due to tightly controlled HVAC systems, are interpretive and not directly validated by guest perception data. These should be viewed as theoretical hypotheses rather than confirmed mechanisms. Future research incorporating review sentiment analysis, occupant comfort surveys, or qualitative interviews would be valuable in confirming or challenging these interpretations.

- This study did not control for key confounding variables such as hotel class, geographic region, or guest demographic composition, all of which can significantly influence guest satisfaction ratings. For instance, luxury hotels may provide exceptional service or amenities that compensate for any perceived limitations associated with green building features, potentially masking dissatisfaction. Similarly, regional climate can affect the performance and perception of HVAC and energy systems. Future research should incorporate these covariates to better isolate the independent effect of LEED credits on guest satisfaction outcomes.

- Furthermore, no formal sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the model’s response to variations in specific sustainability measures. While Random Forest provides useful feature importance rankings, future research could employ sensitivity testing to simulate practical changes in sustainability strategy and their estimated effects on guest satisfaction.

These limitations highlight the need for further research, particularly longitudinal studies that can track changes in guest satisfaction as hotels progress through different certification levels. Future investigations should also explore additional factors, such as geographic location, hotel classification, regional market dynamics, and guest demographics, that may mediate or confound the observed relationships. For instance, regional differences in climate or cultural expectations may influence satisfaction with specific sustainability measures (e.g., thermal comfort or water efficiency). Integrating geospatial or user-level metadata into future studies would help disentangle these effects. Such insights will be crucial in refining green building practices to ensure that sustainability initiatives are both effective and aligned with the evolving expectations of hotel guests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; Methodology, M.G.; Software, M.G.; Validation, M.G. and M.T.; Formal analysis, M.G.; Investigation, M.G. and M.T.; Resources, M.G.; Data curation, M.G. and S.N.; Writing—original draft, M.G. and S.N.; Writing—review & editing, M.G. and M.T.; Visualization, M.G.; Supervision, M.G.; Funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by Aspire Published Scholarship Support Program through Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human participants, personal data, or any form of direct data collection from individuals. All data used were publicly available through the U.S. Green Building Council LEED Project Directory and online travel review platforms. Therefore, ethical review and approval were not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from publicly accessible sources: LEED certification data from the U.S. Green Building Council’s Project Directory (Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/projects (accessed on 25 March 2025). Guest satisfaction data from publicly available hotel reviews on Expedia, Booking.com, TripAdvisor, and other platforms. Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bohdanowicz, P. Environmental Awareness and Initiatives in the Swedish and Polish Hotel Industries—Survey Results. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 662–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G.; Lehmann, L.V.; Scott, D. Tourism and Water Use: Supply, Demand, and Security. An International Review. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Lee, J.S. Empirical Investigation of the Roles of Attitudes toward Green Behaviors, Overall Image, Gender, and Age in Hotel Customers’ Eco-Friendly Decision-Making Process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://readymag.website/usgbc/hospitality/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Millar, M.; Baloglu, S. Hotel Guests’ Preferences for Green Guest Room Attributes. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2011, 52, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable Hotel Practices and Nationality: The Impact on Guest Satisfaction and Guest Intention to Return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Ng, C.Y.N.; Kim, Y.S. Influence of Institutional DINESERV on Customer Satisfaction, Return Intention, and Word-of-Mouth. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, H.; Merrilees, B.; Herington, C. Towards an Understanding of Total Service Quality in Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E.; Srinivasan, S.S. E-Satisfaction and E-Loyalty: A Contingency Framework. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Green Hotel Choice: Testing the Effect of Environmental Friendly Activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030|UN Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/global/publication/tourism-and-sustainable-development-goals-journey-2030 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- USGBC LEED Green Building Rating System Committees; US Green Building Council. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/leed (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Guo, X.; Lee, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S. Occupants’ Satisfaction with LEED- and Non-LEED-Certified Apartments Using Social Media Data. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G. Development and Validation of a Post-Occupancy Evaluation Model for LEED-Certified Residential Projects. In Proceedings of the 2022 (6th) Residential Building Design & Construction Conference, State College, PA, USA, 11–12 May 2022; Volume 6, pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G. A Post-Construction Evaluation of Long-Term Success in LEED-Certified Residential Communities. EPiC Ser. Built Environ. 2022, 3, 758–766. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G.H. Pathways to Project Effectiveness in Sustainable Communities: Insights from a Residential Satisfaction Evaluation Model. J. Archit. Eng. 2025, 31, 04025014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, D. Integrated Analysis of Energy, Indoor Environment, and Occupant Satisfaction in Green Buildings Using Real-Time Monitoring Data and on-Site Investigation. Build. Environ. 2020, 182, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, B.; Hong, J.; Zhu, Y. Occupant Satisfaction in Three-Star-Certified Office Buildings Based on Comparative Study Using LEED and BREEAM. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, B.; Raymond, L. Sustainable Development Practices in the Hospitality Industry: An Empirical Study of Their Impact on Customer Satisfaction and Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaali, H.S.; Usman, I.M.S.; Alqawzai, S. Relationship between Indoor Environmental Quality and Guests’ Comfort and Satisfaction at Green Hotels: A Comprehensive Review. Open Eng. 2024, 14, 20240042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, M.Á.; Monferrer, D.; Estrada, M.; Rodríguez, R.M. Environmental Sustainability and the Hospitality Customer Experience: A Study in Tourist Accommodation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Seshadri, K.; Pattupogula, V.P.D.; Badrinath, C.; Liu, S. Visitors’ Satisfaction towards Indoor Environmental Quality in Australian Hotels and Serviced Apartments. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Q.; Murai, F.; Braham, W.W.; Samuelson, H.W. Learning Building Occupants’ Indoor Environmental Quality Complaints and Dissatisfaction from Text-Mining Booking.Com Reviews in the United States. Build. Environ. 2023, 237, 110319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floričić, T. Sustainable Solutions in the Hospitality Industry and Competitiveness Context of “Green Hotels”. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Chi, O.H.; Xu, X.; Kennedy, I. Narrowing the Intention-Behavior Gap: The Impact of Hotel Green Certification. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Chan, E.K.; Wan, L.C. How Eco-Certificate/Effort Influences Hotel Preference. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 101, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró-Signes, A.; Segarra-Oña, M.D.V.; Verma, R.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Vargas-Vargas, M. The Impact of Environmental Certification on Hotel Guest Ratings. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://amtivo.com/us/iso-certification/iso-14001-environmental-management-system/?gad_campaignid=21701195212 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Gerdt, S.O.; Wagner, E.; Schewe, G. The Relationship between Sustainability and Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality: An Explorative Investigation Using EWOM as a Data Source. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.Y.; Chu, R. Determinants of Hotel Guests’ Satisfaction and Repeat Patronage in the Hong Kong Hotel Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinot, E.; Giannelloni, J.L. Do Hotels’ “Green” Attributes Contribute to Customer Satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospitality 2015: Game Changers or Spectators?|PDF|Brand|Tourism. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/47993670/Hospitality-2015-Game-changers-or-spectators (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding How Consumers View Green Hotels: How a Hotel’s Green Image Can Influence Behavioural Intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimie, C.O.; Biu, E.O.; Ijomah, M.A.; Arimie, C.O.; Biu, E.O.; Ijomah, M.A. Outlier Detection and Effects on Modeling. Open Access Libr. J. 2020, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Regression Diagnostics; SAGE Publications Incorporated: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP—A Fresh Way to Do Statistics. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Hayes, A.F.; Little, T.D. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 732. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G. Investigating LEED-ND key criteria for effective sustainability evaluation. J. Green Build. 2024, 19, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; West, S.G.; Levy, R.; Aiken, L.S. Tests of Simple Slopes in Multiple Regression Models with an Interaction: Comparison of Four Approaches. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2017, 52, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).