The Role of Temporary Architecture in Preserving Intangible Heritage During the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Holy Karbala: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ▪

- How do current temporary architecture projects in Holy Karbala influence the preservation of intangible heritage during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage?

- ▪

- How can temporary architecture be designed to respect and enhance Holy Karbala’s traditional architectural and cultural values, especially during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage?

2. Methodology

- ▪

- The existing examples were studied to build a comprehensive understanding of similar rituals and events that suggested other insights to serve the purpose of this study.

- ▪

- Structured surveys and expert questionnaires were completed with urban planners, architects, and heritage specialists. The surveys aimed to gather professional opinions on the effectiveness, challenges, and design considerations of temporary architecture in Holy Karbala. The questionnaire covered policy implications, community engagement, and cultural sensitivity.

- ▪

- To ensure the data collected was relevant, deep, and rich, this study used a purposive sampling strategy to select the experts. This was appropriate given the specialized nature of the research topic, which cuts across architecture, urban planning, heritage conservation, and religious event management.

- ▪

- The purposive sampling allowed us to select individuals with proven expertise and deep context knowledge of the topic under study, specifically those with academic qualifications or field experience in designing, evaluating, or implementing temporary structures for major religious events such as the Arbaeen Pilgrimage.Sample selection criteria were as follows:

- ○

- Academic or professional specialization in architecture, urban design, or heritage conservation;

- ○

- Involved in projects related to temporary religious structures or mass cultural events;

- ○

- Diverse institutional affiliations (universities, government agencies, NGOs);

- ○

- Variety in years of professional experience (from novice to experienced experts);

- ○

- Geographical diversity includes experts from Iraq, Arab countries, and foreign countries;

- ○

- The goal was not to achieve general statistical representation but to achieve analytical generalization by engaging multiple and content-rich perspectives. This approach ensured the data collected was relevant to the research objectives and could provide in-depth insights into the symbolic, functional, and urban dimensions of temporary structures in a unique religious and cultural context.

- ▪

- Field observations were performed during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage to document the spatial characteristics, functionality, and integration of temporary structures within the historic urban fabric. The observations recorded the materials used, design strategies, and overall visual and cultural impact of the structures. In addition, the data from the surveys and questionnaires were quantitatively analyzed to identify trends and correlations. Statistical methods were applied to expert opinions and public feedback to determine the key factors that contribute to the success of temporary architecture in heritage conservation.

2.1. Global Case Studies

- ▪

- Gion Matsuri Festival, Kyoto, Japan: One of the major cultural events of the city of Kyoto is the Gion Matsuri, a traditional festival. Visitors and hosts are accommodated with the use of temporary buildings such as tents and platforms that also serve as venues. Their construction must connect with the historical character of the city while preserving traditional design features (1). The temporary structures support the continuity of the festival and enhance Kyoto’s cultural heritage while preserving the traditional ambiance of the city (2), see Figure 3.

- ▪

- Covent Garden Market, London, United Kingdom: Despite significant modernization challenges, Covent Garden Market in London is still considered a historic landmark [20]. During renovations, temporary structures were used to house market activities and provide public spaces. These structures were designed to blend with the historical character of the market [21]. The temporary structures helped preserve the market’s historical character while allowing ongoing commercial activities without disrupting the historic fabric, see Figure 4 [22].

- ▪

- Edinburgh Festival, Scotland: The Edinburgh Festival is one of the world’s largest arts festivals, drawing thousands of visitors to the city each year [23]. Temporary theaters and performance spaces are constructed throughout the historic city. These structures are lightweight and mobile, facilitating festival activities without affecting historic buildings [24]. Temporary architecture supports the festival’s operations and enhances cultural events while preserving Edinburgh’s historic urban environment, see Figure 5 [25].

- ▪

- Carnival festivities in Brazil: Carnival festivities in Brazil date back to 1723, with the Portuguese immigrants from the islands of Acores, Madeira, and Cabo Verde introducing the Extrude. During the 1840s, masquerade carnival balls set to polkas and waltzes became popular [26]. Towards the end of the century, the carnival became a working-class festivity where people wore costumes and joined the parade accompanied by musicians playing string instruments and flutes. Carnival was also used during the years of military censorship to express political dissatisfaction. Temporary structures such as performance stages and tents are set up to accommodate visitors and artists [27], see Figure 6. Temporary architecture supports cultural activities and promotes local heritage, maintaining the historical character [28].

- ▪

- Rose Monday Festival in Germany: The annual Rhine Carnival began in 1823, when the city of Cologne decided to set 11 November of each year as the beginning of the celebrations of the festival, which lasts until March. On this day, people go out in disguise and wear colorful clothes to the public squares where different musical groups gather to celebrate the start of the first day of the carnival, which is considered an opportunity to have fun and break free from the constraints of life (3). With thousands of people taking part, the “Flower Monday” festival, celebrated by the regions along the Rhine River in Germany, is held on Monday, the most important event of the “annual Rhine Carnival”. Temporary structures, like tents and exhibition spaces, are shown in Figure 7. These structures are designed to complement the city’s historical and scenic environment. The temporary structures enable the festival to be held successfully without impacting historic landmarks (4).

2.2. Questionnaires

2.2.1. Expert Panel Composition and Qualifications

2.2.2. Statistical Tests and Measures Employed

2.2.3. Exploring Temporary Architecture and Intangible Heritage in the Arbaeen Pilgrimage

2.3. Analysis and Descriptions of the Survey

2.3.1. Impact of Temporary Architecture on Heritage Preservation

2.3.2. Design Considerations for Temporary Structures

2.3.3. Community Involvement

2.3.4. Regulatory and Policy Framework

2.3.5. Examples of Successful Projects

3. Results

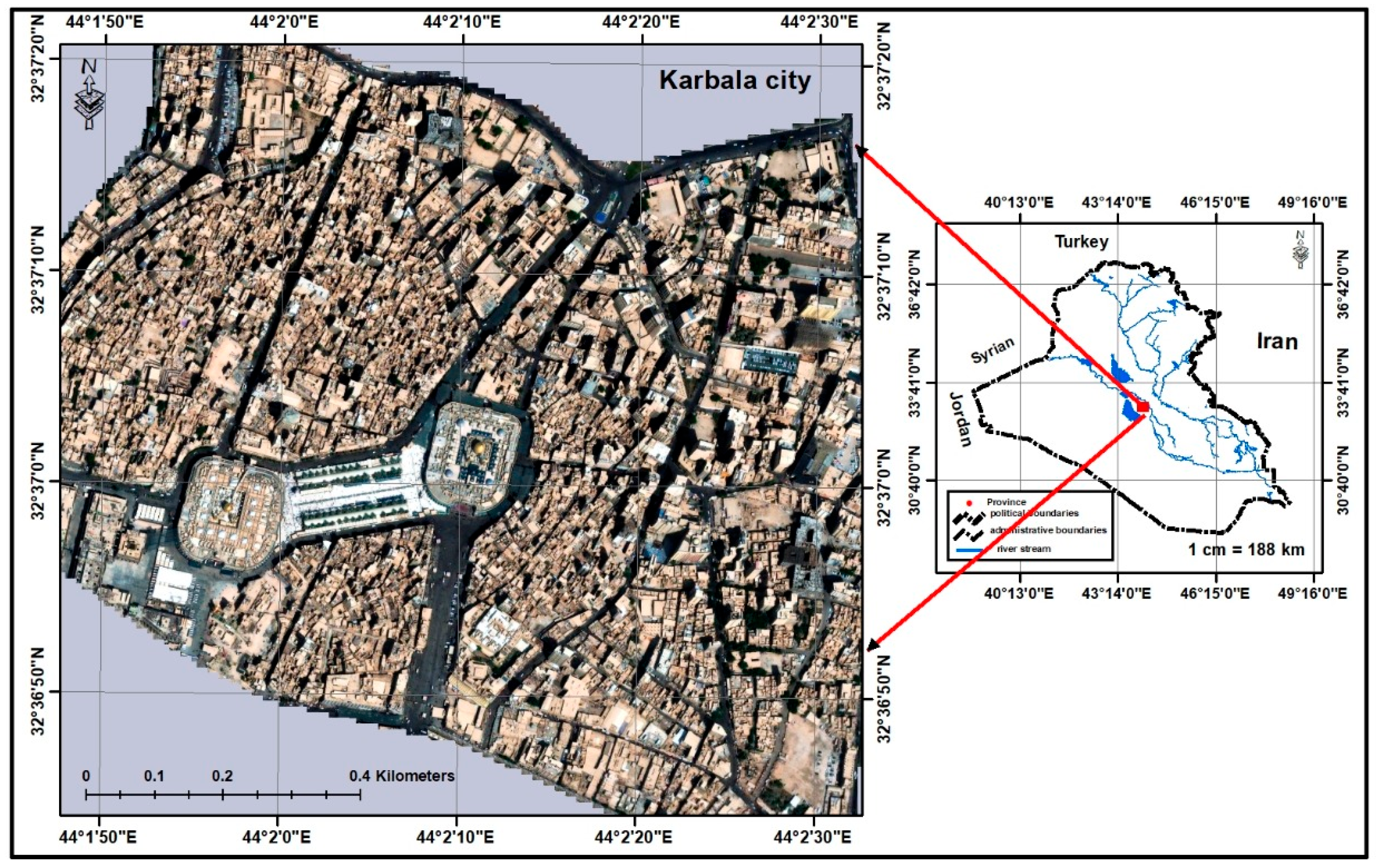

3.1. Historical Significance and Urban Transformation

- ▪

- Holy Karbala is a main pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims, home to the shrine of Imam Hussein, a key figure in Islamic history. The Arbaeen Pilgrimage, one of the biggest in the world, makes Holy Karbala even more important as millions of pilgrims come every year. This pilgrimage not only highlights the city’s religious importance but also an intangible cultural heritage that has been kept for centuries.

- ▪

- Holy Karbala’s historical background is reflected in its old urban fabric, traditional architecture, and cultural landscape that has been developed over time. The city’s architecture and urban form are deeply connected to its religious and cultural history, so it is a key site to study the conservation of both tangible and intangible heritage, especially during Arbaeen.

- ▪

- Holy Karbala is undergoing rapid modernization driven by economic growth and the influx of pilgrims—especially during the massive Arbaeen Pilgrimage. That growth is driving urban expansion but also threatening the city’s historical heart and soul. What that development really highlights is the need to find a balance between modern demands and cultural continuity—that means preserving the city’s intangible heritage.

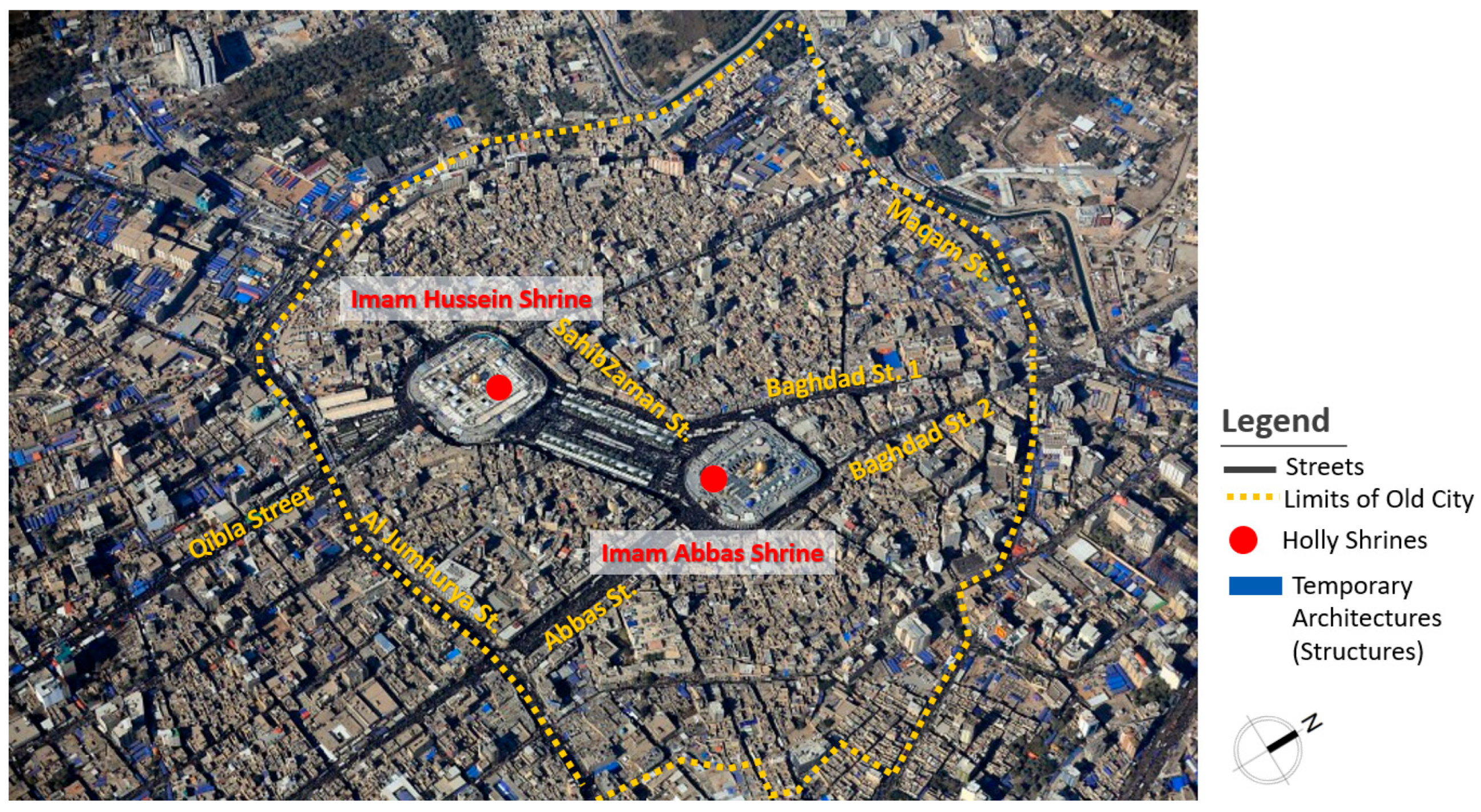

3.2. Existing Temporary Architecture

- ▪

- Holy Karbala uses temporary architecture to accommodate millions of pilgrims during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage [6]. These structures, including tents, shelters, and other temporary facilities, are essential in providing services without altering the city’s historical landscape permanently. Studying these structures gives us valuable ideas on their role in heritage preservation during big religious events [29].

- ▪

- Analyzing the current use of temporary architecture during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage provides opportunities to develop better practices and strategies. These strategies can enhance the effectiveness of temporary structures in preserving the city’s cultural heritage while meeting the demands of such large gatherings [30].

- ▪

- Figure 9 shows that the temporary tents in Holy Karbala, during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage, are a mixed bag. They come in all shapes and sizes, and are just as irregularly placed along sidewalks and streets. That haphazard placement—where they encroach on public space—disrupts both pedestrian and vehicular flow. People are forced onto the roads, which compromises safety—especially during peak pilgrimage times. The visibility of permanent buildings becomes obstructed, which diminishes the city’s architectural identity and makes its urban legibility suffer. Those tents’ inconsistent materials, colors, and forms fragment the streetscape and degrade the visual quality of the city. Without planning, they can do more harm than good to the cultural and spiritual essence of the place.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

- ▪

- A Chi-Square Test was conducted to assess the relationship between years of professional experience and the perceived importance of temporary architecture. The test yielded a Chi-Square value of 12.56 with 6 degrees of freedom and a p-value of 0.028. Since the p-value is below the conventional threshold of 0.05, the result indicates a statistically significant association between the two variables. This suggests that professionals with greater experience are more likely to recognize and value the role of temporary architecture, highlighting the influence of practical exposure on expert judgment in this field.

- ▪

- A Multiple Regression Analysis was conducted to evaluate how two key variables—use of traditional materials and community involvement—influence cultural identity compatibility. The model demonstrated a high explanatory power, with an R-squared value of 0.90, indicating that 90% of the variance in cultural identity compatibility can be explained by the two predictors. Both variables showed statistically significant effects: traditional materials had a Beta coefficient of 0.75 (p = 0.001), while community involvement had a Beta of 0.60 (p = 0.005). These findings suggest that incorporating traditional architectural elements and fostering active participation from local communities both contribute meaningfully to enhancing cultural alignment. Notably, the use of traditional materials emerged as the stronger predictor in the model.

- ▪

- The Pearson correlation analysis revealed a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between the use of traditional materials and cultural identity compatibility (r = 0.92, p = 0.001), indicating that greater incorporation of traditional materials is closely associated with higher alignment to cultural identity. However, due to the absence of raw data, a full correlation matrix—including potential relationships between other variables such as community involvement—could not be generated, limiting the scope of multivariate insights.

3.4. Cultural and Intangible Heritage

- ▪

- The Arbaeen Pilgrimage is not only a religious event but also a manifestation of Holy Karbala’s intangible cultural heritage. It involves traditional practices, rituals, and communal activities that have been passed down through generations [31]. Temporary architecture during this period plays a crucial role in supporting these cultural practices by providing spaces for rituals, hospitality, and community gatherings, thereby preserving cultural continuity [32].

- ▪

- The local community’s involvement in organizing and maintaining the Arbaeen Pilgrimage is integral to preserving Holy Karbala’s intangible heritage. Investigating how temporary architecture can facilitate and enhance this community involvement helps in understanding its role in maintaining cultural traditions and heritage [33], see Figure 10.

- ▪

- That is where the images in Figure 10 come in. They show how Holy Karbala’s urban spaces are transformed into vibrant cultural corridors during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage. Images 1 and 2 capture camel processions moving through the streets, turning ordinary roadways into stages for symbolic and spiritual performances. Those performances connect contemporary rituals with historical narratives. Images 3 and 4 show community-organized stalls offering services, crafts, and traditional goods. That highlights the local community’s active role in preserving and expressing cultural identity. Those temporary interventions really bring out the power of public space to host intangible heritage practices and foster communal engagement.

- ▪

- However, those cultural activities also present some urban challenges. As Image 3 shows, camel processions occupy major roads, interrupting standard movement and requiring traffic rerouting. Temporary installations partially obstruct the visual integrity of the streetscape, masking permanent architecture and altering spatial legibility. While enriching the cultural atmosphere, those interventions also underscore the need for thoughtful planning that balances heritage expression with urban order and accessibility.

3.5. Sustainability Potential and Strategic Value

- ▪

- Holy Karbala, especially during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage, needs balancing between the millions of visitors and the city’s historical and cultural identity [34]. This study aims to explore how temporary architecture can contribute to sustainable urban development by addressing these two objectives [7].

- ▪

- The experience of Holy Karbala with temporary architecture during the Arbaeen Pilgrimage can be a model for other historical cities that face similar challenges [35], especially in other Iraqi cities that have holy shrines and heritage fabric. These lessons can help in integrating temporary architecture in heritage preservation, especially in events of large-scale religious or cultural [36].

- ▪

- Karbala’s rich history and the scale of the Arbaeen Pilgrimage make it the perfect place to explore how temporary architecture can support that preservation. The lessons learned here can inform preservation strategies not just in Karbala but in other cities with a similar cultural significance. Policymakers, planners, and architects need to be guided in how to balance the demands of the present with the need to conserve the past.

3.6. Impact of Temporary Architecture on Heritage Preservation

- ▪

- Temporary construction is a vital tool in heritage conservation. It supports the events that keep intangible cultural practices alive—like the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Karbala. Most experts (75%) agree that temporary structures have a positive impact. They provide essential infrastructure and reinforce the city’s cultural and religious identity. When those structures are designed with traditional styles in mind, they can enhance the historical character of a place and make it feel more authentic. But 25% of experts are concerned about the negative impacts of poorly integrated temporary architecture. That can block landmarks, disrupt the way a place looks and feels, and diminish its esthetic and cultural value. That is why careful planning and design that is sensitive to the local context are so important. Temporary interventions should protect and enrich heritage environments, not undermine them.

3.7. Design Considerations for Temporary Structures

- ▪

- In temporary buildings in a historical setting, 85% of the professionals agree that tradition is key. By using traditional materials and architectural motifs, temporary buildings blend in with the environment, preserve the city’s visual character, and the cultural fabric. This not only safeguards the heritage sites but also ensures that these structures reinforce the visual and cultural continuity of the built environment rather than disrupt it. To stick to the architectural language of the past in modern interventions creates a balance between tradition and innovation and preserves the city’s identity.

- ▪

- Equally important is flexibility and adaptability, a priority for 70% of the experts. Temporary structures should be designed to be functionally versatile to accommodate different uses and be easily dismantled or repurposed. This flexibility minimizes the disruption to the historical environment and allows spaces to evolve according to the needs without imposed permanent changes. By incorporating modular, reusable, and context-sensitive design strategies, temporary architecture can be a dynamic yet non-intrusive solution, enhancing urban resilience while preserving the historical fabric.

3.8. Community Involvement and Successful Projects

- ▪

- Local community participation has a big impact on the design and planning of temporary buildings, with 65% of experts advocating for high local involvement. By including community input, temporary structures are more relevant and accepted and are a tool for intangible heritage conservation. This active participation gives residents a sense of ownership and belonging, which makes temporary solutions more effective and sustainable.

- ▪

- On the other hand, 30% of experts recommend a balanced approach that combines community input with professional expertise. They say that while local knowledge is valuable, combining it with architectural and preservation standards ensures temporary structures are both culturally significant and structurally sound. This level of involvement allows for an optimized design process where expert guidance enhances community-driven ideas and blends tradition with technical precision. In the end, this results in functional, resilient, and contextually appropriate temporary buildings.

- ▪

- Successful examples of temporary architecture showing its potential to enhance cultural events and heritage preservation when done with respect to the traditional. Experts point to projects where temporary structures like pavilions sit beautifully within historic contexts, enriching both spatial and social experiences without compromising authenticity. These show how temporary architecture can activate heritage spaces in flexible and meaningful ways. But poorly planned interventions without consideration of scale, materials, and harmony can disrupt the visual and cultural fabric of the heritage site. So, thoughtful design, contextual awareness, and strategic decision making are key to making temporary architecture complement rather than compete with its surroundings.

3.9. Regulatory and Policy Framework

- ▪

- Rules and regulations for temporary buildings in heritage areas are a big issue; 80% of respondents think we need clear guidelines and standards. Experts want a structured regulatory framework with design standards, safety protocols, and heritage conservation measures so that temporary structures blend in and contribute positively to the site. Also, there is a call to update existing regulations to address current challenges, especially with modern design and new materials. This should be an ongoing process, adapting to emerging needs and ensuring the integration of temporary architecture in a heritage context. Experts also stress the need for a body to oversee, plan, and regulate religious ceremonies and rituals in culturally significant areas.

- ▪

- Twenty percent of experts agree that the existing regulations provide a general framework but say that the guidelines are not enough to address modern temporary architecture. This view highlights the need to refine policies to evolve with architectural and urban changes. The discussion underlines the need for a dynamic and flexible regulatory system that not only preserves the historical and cultural integrity of the site but also accommodates modern design and society’s evolving needs.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Main Activities Related to the Visit

- ▪

- Visiting the holy shrines, accompanied by religious rituals such as prayer and reading the Quran;

- ▪

- Serving visitors, where temporary structures are formed in which service processions are held, including the following: cooking, feeding, housing, and all possible services for the comfort of the visitor, including health services and bathrooms;

- ▪

- Processions of other events, which are ritual events performed in groups and practiced in the streets in the form of a sad carnival, such as the following: (Tashabeeh-Zanjeel and Aza and other group events);

- ▪

- There are other activities (non-religious) that are also practiced by the people of Karbala and those who come to it during the days of the visit, which may require temporary structures and locations within the city’s roads, such as the extensive commercial movement. In addition to this, there are cultural institutions that work on several educational practices in temporary alternative structures.

4.2. The Role of Temporary Architecture

- ▪

- Tents and pavilions include large tents and pavilions that are erected to provide shelter, food, and medical services to pilgrims. These structures are designed to be easily assembled and disassembled, catering to the short-term nature of the event [41]. Prayer areas are temporary prayer spaces set up to accommodate the large number of worshippers. These areas are often located near key religious sites, such as the shrine of Imam Hussein [28]. Sanitation facilities consist of portable toilets and washing stations, which are installed to maintain hygiene and support the large influx of visitors [27], see Figure 11.

- ▪

- Temporary structures are often designed to respect and reflect traditional Islamic architectural styles, ensuring that they blend harmoniously with the historic character of Holy Karbala [42]. The design emphasizes functionality to handle the high volume of people efficiently. Features include easy access, ventilation, and durability to withstand the event’s demands [43].

4.3. The Impact on Heritage Preservation

- ▪

- The encouraging impacts often became apparent due to the temporary architecture that enabled the city to handle the logistical challenges posed by large numbers of pilgrims, ensuring that the religious experience was smooth and organized.

- ▪

- Community engagement is always achieved by the local businesses and communities who are often involved in setting up and managing these structures, fostering a sense of participation and connection to the event.

- ○

- Challenges and concerns that include the impact and maintenance. The impact of temporary structures on the historical urban fabric can lead to the deterioration of the traditional urban fabric, particularly if not carefully integrated. Issues include encroachment on historical sites and visual impact on the city’s skyline. The maintenance of cultural continuity appears when the temporary structures do not detract from the city’s cultural and architectural heritage requires careful planning and design.

4.4. Examples of Temporary Architecture During Arbaeen Pilgrimage

- ▪

- Case Study 1: Tent Cities Near the Shrine: Large tent cities are set up around the shrine of Imam Hussein to accommodate pilgrims. These areas provide essential services and create a temporary but organized space for the influx of visitors.

- ▪

- Case Study 2: Temporary Medical Facilities: Mobile clinics and first-aid stations are established to offer medical care during the event. These facilities are designed to be easily movable and responsive to the needs of the pilgrims, see Figure 12.

4.5. Practices and Accommodations

- ▪

- Design temporary structures with attention to the historical and cultural context of Holy Karbala. Use traditional materials and architectural styles to blend with the city’s heritage;

- ▪

- Engage local stakeholders in the planning and implementation of temporary architecture to ensure that it supports the community’s needs and maintains cultural continuity;

- ▪

- Consider the environmental impact of temporary structures and incorporate sustainable practices in their design and construction to minimize waste and resource consumption.

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- ▪

- Allowing the community of Karbala to participate in the creation, planning, and designing of temporary architectural structures is an assurance that such structures will reflect the cultural values of the people. Efforts to educate people, therefore, need to focus on the role that these structures have in preserving the part Karbala’s legacy.

- ▪

- Temporary architecture, on the other hand, has to be clear with its instructions for design, safety, as well as history for continuity in development. Essentially, this means that the design standards should be in line with what is required by history and the present identity and character of Karbala, both at the same time.

- ▪

- Elements, materials, and Karbala’s historic character designs should be present in future temporary constructions to guarantee cultural continuity and visual consistency between temporary and permanent buildings in the city.

- ▪

- Using eco-friendly materials, energy-efficient design, and modular construction will minimize the environmental impact of temporary structures. Planning for reuse and repurposing will also enhance sustainability and reduce waste.

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

7.1. Research Limitations

- ▪

- The research did not use advanced spatial tools such as Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA), Isovist modeling, or Urban Network Analysis (UNA) indicators like closeness and betweenness centrality. These could have helped us understand spatial legibility, pedestrian flows, and how temporary structures interact with the street network of Holy Karbala.

- ▪

- The study did not assess solar exposure, wind flows, or microclimatic effects, which are crucial for designing comfortable and sustainable temporary structures in densely populated pilgrimage contexts.

- ▪

- The global case studies lacked detailed floor plans or spatial diagrams. Although descriptive analysis was used, visual data would have been helpful for spatial clarity and accessibility, especially for multidisciplinary and non-specialist audiences.

7.2. Future Research Directions

- ▪

- Future work should look into how other heritage cities—Kyoto, Istanbul, and Rome—use temporary architecture during cultural or religious events, and what the global patterns and context-sensitive best practices are.

- ▪

- How can artificial intelligence, digital fabrication, and sustainable materials enhance the adaptability, efficiency, and ecological impact of temporary structures in historical urban spaces?

- ▪

- How can participatory design methods and robust policy interventions influence the cultural relevance, social acceptance, and regulatory integration of temporary architecture during religious events like Arbaeen?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woźniak-Szpakiewicz, E. Image of a Place: The Relationship Between Urban Heritage and Temporary Architecture; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Imperadori, M.; Brunone, F. Insegnare costruendo-architettura temporanea tra ricerca e didattica teaching and building-temporary architecture between research and didactics. Agathón 2018, 4, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tunçbilek, G.Z. Temporary Architecture: The Serpentine Gallery Pavilions. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duksi, A.; Küçükali, U.F. Sustainable temporary architecture. A+Arch Des. Int. J. Archit. Des. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, S.L.; Nasar, Z.A. Urban identity in the holy cities of Iraq: Analysis of architectural design trends in the city of Karbala. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2020, 14, 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, S.L.; Alobaydi, D.; Anton, D.; Nasar, Z. Analysing the master plan development and urban heritage of Najaf City in Iraq. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 15, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, S.A. Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.R.; Al-Thahab, A.A. Maintaining Identity of the Built Environments of Religious Cities: Impact of Expansions at the Historic Karbala, Iraq. ISVS E-J. 2023, 10, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçbilek, G.Z. Temporary architecture. In Proceedings of the 2nd ICAUD International Conference in Architecture and Urban Design, Tirana, Albania, 8–10 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Borgianni, S.; Serrani, V. Design for Emergency: Temporary Architecture. In Research Tools for Design: Spatial Layout and Patterns of Users Behaviour; Setola, N., Ed.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2011; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jid, H. Visitors accommodations: Khans between Najaf and Karbala. Yanabee Alhikmeh 2006, 10, 50–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Al-Ansari, R.M. Holy Shrines of Karbala: Architectural Study with a Historical Background of the Area Between and Around the Two Holy Shrines of Karbala-Iraq. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stuedi, P.; Trivedi, A.; Pfefferle, J.; Klimovic, A.; Schuepbach, A.; Metzler, B. Unification of Temporary Storage in the {NodeKernel} Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2019 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 19), Renton, WA, USA, 10–12 July 2019; pp. 767–782. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu, M.; Ungureanu, V.; Grecea, D.; Petran, I. Conversion of a Temporary Tent with Steel Frame into a Permanent Warehouse. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 245, p. 22056. [Google Scholar]

- Badina, A.; Annie, M.L. Temporary Architecture as a Tool to Revitalized Disused Places, Through the Case Study of Paris Former Circular Railway. Master’s Thesis, Polytechnic of Milan, Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nsaif, H.; Salman, A.; AbdulAhaad, E. Evaluation of temporary architecture in Iraq (An applied study of camps for the displaced). In Proceedings of the 1st International Multi-Disciplinary Conference Theme: Sustainable Development and Smart Planning, IMDC-SDSP 2020, Cyperspace, 28–30 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, L.R.; Alobaydi, D. Studying Sustainable Actions of Syntactic Structures of Historic Hit Citadel: A Morphological Approach. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 881, p. 012034. [Google Scholar]

- Albabely, S.; Alobaydi, D. Impact of Urban Form on Movement Densities: The Case of Street Networks in AlKarkh, Baghdad, Iraq. ISVS E-J. 2023, 10, 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Al Hashimi, H.; Alobaydi, D. Measuring Spatial Properties of Historic Urban Networks. In AIP Conference Proceeding; AIP Publishing: New York City, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2651. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrecht, N. Covent Garden: The Untold Story: Dispatches from the English Culture War, 1945–2000; UPNE: Lebanon, NH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, R. Covent Garden: Its Romance and History; Simpkin Marshall Hamilton, Kent & Company Limited: London, UK, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, A.F.G. The Role of Cultural Flagships in the Perception and Experience of Urban Areas for Tourism and Culture: Case Study: The Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. Ph.D. Thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bartie, A. Cultural interactions at the Edinburgh Festivals, C. 1947–1971. Arts Int. Aff. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carlsen, J.; Ali-Knight, J.; Robertson, M. Access—A research agenda for Edinburgh festivals. Event Manag. 2007, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, J. Cultural effects of the Edinburgh International Festival: Elitism, identities, industries. Contemp. Theatre Rev. 2003, 13, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Lorena, C.D. Insights for the analysis of the festivities: Carnival seen by Social Sciences. Rev. Lusófona De Estud. Cult. Lusoph. J. Cult. Stud. 2019, 6, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Porto, A.F. Culture and tourism: Perspectives of foreigners on the Brazilian carnival. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 139, 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Jaguaribe, B. Carnival crowds. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 61, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabila, R. Sites of Worship: From Makkah to Karbala; Reconciling Pilgrimage, Speculation and Infrastructure. In Urban Design in the Arab World: Reconceptualizing Boundaries; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba Husein, U. A phenomenological study of Arbaeen foot pilgrimage in Iraq. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto, E. Beyond the Karbala Paradigm: Rethinking Revolution and Redemption in Twelver Shi’a Mourning Rituals. J. Shi’a Islam. Stud. 2013, 6, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostowlansky, T. Managing Karbala: Genealogies of Shi’a humanitarianism in Pakistan, England, and Iraq. In Political Theologies and Development in Asia; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020; pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali, A.H. Karbala and Ashura Flowed by Ziyara Ashura and Ziyara Al-Warith; Ansariyan Publications: Qom, Islamic Republic of Iran, 2022; p. 45. Available online: https://al-islam.org/printpdf/book/export/html/18646 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Litvak, M. The Shi’i Ulama of Najaf and Karbala, 1791–1904: A Sociopolitical Analysis; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Raeda, A.-D.; Asadi, S.; Danilina, N. Strategic urban planning of religious cities: The case study of karbala city in iraq. Вестник МГСУ 2020, 15, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Jurn, K. Kerbela: A Universal City, Ciwas Third Annual Conference on ‘Urban Islam: Muslim Minorities, Identity and Tradition in West Asian, South Asian, and African Cities’; Royal Halloway, University of London: Egham, UK, 2020; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Alobaydi, D.; Mohamed, H.; Attya, H. The Impact of Urban Structure Changes on the Airflow Speed Circulation in Historic Karbala, Iraq. Procedia Eng. 2015, 18, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, M. Shi’i Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: The ’Ulama’ of Najaf and Karbala; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulredha, M.; Alkhaddar, R.M.; Jordan, D.; Alattabi, A.W. Facing Up to Waste: How Can Hotel Managers in Kerbala, Iraq, Help the City Deal with Its Waste Problem? 2017. Available online: https://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/6526/ (accessed on 13 March 2018).

- Cole, J.R.I.; Momen, M. Mafia, MOB and shiism in IRAQ: The rebellion of Ottoman Karbala 1824–1843. Past Present 1986, 112, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekrenz, Y. The Elementary Forms of Carnival: Collective Effervescence in Germany’s Rhineland. Can. J. Sociol. Cah. Can. De Sociol. 2014, 39, 643–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hussein, M. From Courtyard To Monument: Effect of Changing Social Values on Spatial Configuration of The Cities of the Holy Shrines in Iraq. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Space Syntax Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–3 November 2013; Sejong University Press: Soeul, Republic of Korea, 2013; pp. 038:2–038:23. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85006326577&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&st1=najaf&nlo=&nlr=&nls=&sid=7f47108a8fc9eb4a7d7b14225ab01aa5&sot=b&sdt=sisr&sl=20&s=TITLE-ABS-KEY%28najaf%29&ref=%28architecture%29&relpos=4&citeCnt=0&se (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Al-Musawi, M.H.; Ali, S.H. Temporary Architecture as a Strategy for Stimulating Historic Place. Iraqi J. Archit. Plan. 2024, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NO | Activity’s Name | Descriptions | Types | People | Cities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gion Matsuri Festival | The Gion Matsuri, one of Japan’s biggest festivals, takes place in Kyoto every July, with the main events on the 17th and 24th. Originally begun in 869 CE as a ritual to calm the gods during an epidemic, it is now a major cultural festival that represents Kyoto. The festival is centered around Yasaka Shrine in the Gion district, and the city streets are transformed into ceremonial spaces with yamaboko floats and structures built by local guilds, blending tradition with the city’s urban landscape. | Gion Matsuri is an intangible cultural heritage event. The temporary architecture allows for crowd movement and cultural experience, preserves traditional spatial practices, and encourages community involvement. The festival shows how heritage can live in modern urban life. | Local artisans and carpenters are building wooden floats without nails, preserving ancient building techniques. Residents of Kyoto in traditional clothes, music, and dance. Shinto priests performing ceremonies at Yasaka Shrine. Tens of thousands of domestic and international visitors. | Kyoto, Japan |

| 2 | Covent Garden Market Renovations | Covent Garden Market has been a London landmark since the 17th century and underwent major works in the late 20th and early 2000s. Temporary structures—like modular stalls and covered walkways—allowed the market to continue to operate, be open to the public, and be culturally active. Designed to reflect the site’s neoclassical architecture, these installations preserved the market’s heritage and social life during the phased restoration and showed a model of heritage management. | This approach ensured Covent Garden retained its identity and vibrancy throughout the redevelopment. The temporary architecture played a key role in bridging the past and present and keeping the space relevant to its history and community. | The stakeholders were as follows: (1) GLC and later private developers working under the guidance of heritage and planning authorities. (2) Market traders and local business owners whose livelihoods depended on access to stalls and retail space. (3) Cultural stakeholders, including street performers and artists, who define the site’s intangible heritage. (4) The public who continued to visit the space as a cultural destination. | London, United Kingdom |

| 3 | Edinburgh Festival | The Edinburgh Festival takes place every August and includes big events like the Fringe and International festivals, which attract hundreds of thousands to the UNESCO city. Temporary structures—like mobile theaters, pavilions, and seating—are used citywide to host events while preserving historic architecture and sightlines. Designed to be quick to set up and have minimal impact, these installations allow for big cultural programming without compromising Edinburgh’s heritage. | The type of event is cultural and artistic, held every August, featuring live performances, literature, music, dance, and visual arts. Temporary architecture plays a key role in delivering this large-scale cultural phenomenon, providing flexible, respectful, and inclusive spaces that fit with the historic and civic character of Edinburgh. It shows how temporary structures can activate heritage spaces without compromising their authenticity or value. | The festival involves the following: (1) Artists and performers from around the world. (2) Cultural organizations, including the Edinburgh International Festival Society and Fringe Society. (3) City authorities and heritage conservation bodies to oversee spatial regulations. (4) Local residents and businesses, many of whom host or participate in festival activities. (5) Visitors and tourists who bring cultural and economic energy to the city. | Edinburgh, Scotland |

| 4 | Brazil Festival | Brazil’s Carnival in Rio is a big cultural event with music, parades, and heritage. Temporary structures—like in the Sambadrome or the historic streets of Olinda—support samba schools and folk groups to preserve intangible heritage. These structures enable cultural expression and fit into modern and historic urban environments. | The type of event is a national, religious, and cultural celebration held before Lent, usually in February or March, depending on the Christian calendar. To accommodate millions of participants and spectators, temporary structures are set up across the cities: (1) Mobile stages for music, dance, and public speeches. (2) Tents, pavilions, and kiosks for food, crafts, and community services. (3) Viewing platforms, bleachers, and crowd control installations. (4) Portable sanitation and medical facilities for public health and safety. | The festival involves the following: (1) Samba schools, musicians, and dancers from local neighborhoods. (2) Cultural organizations and local municipalities coordinating logistics and safety. (3) Street vendors, artisans, and community associations. (4) Millions of spectators from all over the world contribute to the festival’s atmosphere and economy. | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Also, other Brazilian cities |

| 5 | Rose Monday Festival (Rosenmontag) | Rosenmontag is the highlight of the Rhineland Carnival and is a centuries-old tradition celebrated in cities like Cologne, Mainz, Düsseldorf, and Bonn. It is held on the Monday before Ash Wednesday and features parades, satire, and costumes that express community identity and political themes. In historic city centers with preserved architecture, the festival uses carefully designed temporary structures that support logistics without disrupting the visual and cultural integrity of the landmarks. This shows how temporary architecture can be functional and preserve heritage in big cultural events. | The type of event is a seasonal, religiously rooted, and cultural festival, taking place in February or March, depending on the Lenten calendar. It is the climax of the Carnival season (Karneval or Fastnacht) in the German-speaking world. A lot of temporary structures are used for the event: (1) Tents and covered pavilions for food, drink, and music. (2) Portable exhibition stands for costumes, crafts, and carnival clubs. (3) Viewing platforms, crowd control barriers, and stages for performances. (4) Mobile sanitation units and first aid stations for safety and comfort. | The festival involves the following: (1) Local Karnevalsgesellschaften (carnival associations) responsible for the floats and performances. (2) Musicians, satirical speakers, costume designers, and float builders. (3) City officials and safety personnel manage the urban logistics. (4) Residents and international tourists, many of whom dress up and participate actively. | Cologne and Rhine Region, Germany |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farhan, S.L.; Attia, H.N.; Rahim, L.A.L.; Alobaydi, D. The Role of Temporary Architecture in Preserving Intangible Heritage During the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Holy Karbala: A Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111787

Farhan SL, Attia HN, Rahim LAL, Alobaydi D. The Role of Temporary Architecture in Preserving Intangible Heritage During the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Holy Karbala: A Case Study. Buildings. 2025; 15(11):1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111787

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarhan, Sabeeh Lafta, Haider Naji Attia, Lama Abd Lmanaf Rahim, and Dhirgham Alobaydi. 2025. "The Role of Temporary Architecture in Preserving Intangible Heritage During the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Holy Karbala: A Case Study" Buildings 15, no. 11: 1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111787

APA StyleFarhan, S. L., Attia, H. N., Rahim, L. A. L., & Alobaydi, D. (2025). The Role of Temporary Architecture in Preserving Intangible Heritage During the Arbaeen Pilgrimage in Holy Karbala: A Case Study. Buildings, 15(11), 1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111787