Reviving Architectural Ornaments in Makkah: Unveiling Their Symbolic, Cultural, and Spiritual Significance for Sustainable Heritage Preservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Historical Background of Islamic Art

2.2. The Influence of the Quran and Sunnah on Islamic Art

2.2.1. Content

- (a)

- Stylisation

- (b)

- Non-Individuation

- (c)

- Repetition

2.2.2. Form

- (a)

- Non-developmental Structure

- (b)

- Arabesque Structure

2.3. Previous Related Studies

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Data Collection

- Historical Documents and Manuscripts:

- Archival records, architectural treatises, and historical manuscripts provide primary references for identifying ornamental motifs.

- Selection criteria focus on documents explicitly describing or illustrating Makkah’s decorative traditions, ensuring reliability in tracing symbolic meanings.

- Photographic Archives and Media:

- A systematic review of historical photographs, videos, and films from reputable digital libraries and archives is conducted.

- Ornamentation samples are selected based on their recurrence across multiple sources, indicating their historical and cultural significance.

- Visual analysis techniques, including pattern recognition and motif comparison, are applied to categorise and interpret these decorative elements.

- Digital Reconstruction and Symbolic Analysis:

- Software tools such as Adobe Illustrator 2024 v28.6 and AutoCAD 2023 v24.2 aid in reconstructing faded or lost details, enhancing the clarity of ornamentation for detailed study.

- The reconstructed motifs are analysed through an interpretive framework, considering their stylistic elements, symbolic connotations, and cultural context.

- The study cross-references reconstructed symbols with historical sources and existing literature on Islamic art and architecture to ensure accurate interpretation.

3.3. Theoretical Framework

3.3.1. Carl Jung’s Theory of the Collective Unconscious

- Collective Heritage: Drawing on Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, the botanical motifs in Makkah’s architectural heritage can be seen as manifestations of universal archetypal symbols—deeply embedded in humanity’s collective memory—reflecting spiritual and cultural values that transcend time and place.

- Symbolism in Architecture: According to Jung, architectural symbols act as conduits for expressing unconscious ideas and cultural narratives. This study explores how Makkah’s ornaments embody deeper symbolic meanings, like arabesque designs and plant-based patterns.

- Religious Contexts: Jung’s focus on religion and mythology underscores the interplay between spiritual identity and collective symbols. The decorative architectural elements in Makkah, infused with Islamic motifs, reflect this dynamic, reinforcing its religious significance.

3.3.2. Lamya Al-Faruqi’s Theory of Tawhid in Islamic Art

- Content: Islamic art avoids depicting humans, animals, or naturalistic forms, emphasising geometric patterns, calligraphy, and stylised plant motifs. These elements affirm the absoluteness of God and His separation from the material world.

- Form: The structure of Islamic art employs non-developmental designs and arabesques that symbolise infinity and transcendence, further reinforcing the Tawhidic principles.

3.4. Analytical Approach

- Symbolic Interpretation: Using Jung’s framework, the study interprets the archetypes and symbolic representations in Makkah’s architectural elements. This involves identifying recurring patterns and themes that resonate with universal human experiences.

- Cultural Contextualisation: Al-Faruqi’s theory is employed to contextualise the symbols within Islamic art’s spiritual and cultural traditions, focusing on their alignment with the principles of Tawhid and their role in reflecting Islamic values.

3.5. Methodological Justifications

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Overview of Decorative Elements

4.1.1. Visual Characteristics

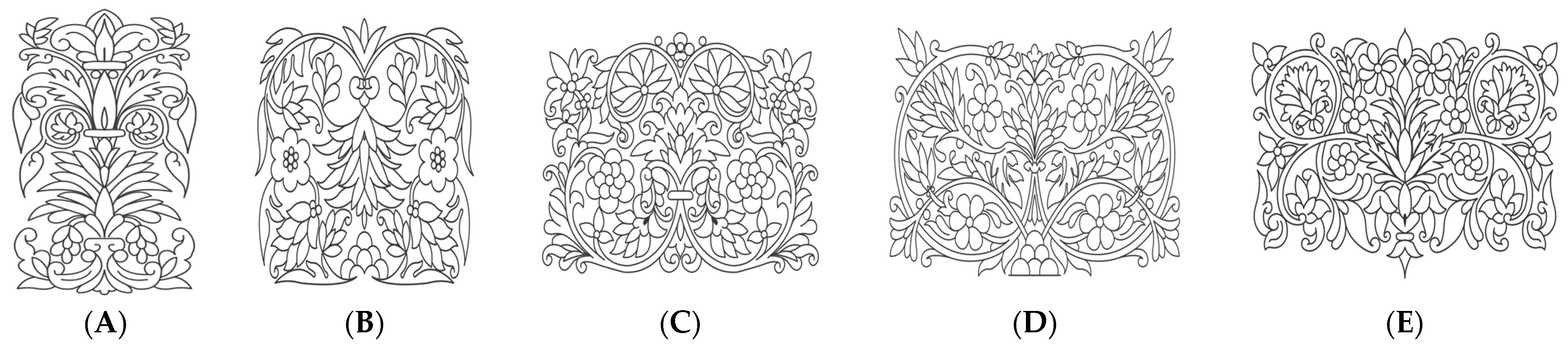

- (a)

- Composition Types

- Palm Tree Compositions: featuring stylised elements derived from palm trees and fronds;

- Pinecone or Fish Scale Motifs: incorporating repeating patterns inspired by pinecones or scales;

- Mixed Compositions: combining palm tree motifs, pinecones, and other botanical or abstract elements.

- (b)

- Materials and Techniques

- Doors: serving as prominent focal points in traditional Meccan architecture;

- Windows and Rawasheen: traditional wooden latticework that balances aesthetics with functionality;

- Built-in Wall Cabinets: enriching the interiors with artistic expression while maintaining utility.

- (c)

- Types of Ornamentation: Botanical Motifs

4.1.2. The Importance of Decorative Elements in Makkah’s Architectural Heritage

4.2. Analysing Makkah’s Decorative Motifs in Light of Carl Jung’s Theory of the Collective Unconscious

4.2.1. Palm Trees: Symbols of Fertility and Spiritual Elevation

- (a)

- Archetypal Symbolism of Palm Trees

- Islamic Perspectives (Palm Trees as Symbols of Divine Care): Hawting [26] highlights the association of palm trees with divine care in Islamic culture, as referenced in the Quran and Hadith. In Surah Maryam (19:23-25), the palm tree plays a pivotal role in Mary’s story, providing sustenance and comfort in a critical moment, reinforcing its symbolism as a sign of divine provision. Additionally, the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) likened the believer to a palm tree, emphasising resilience, stability, and continuous benefit. These religious interpretations enhance the significance of the motif, yet their architectural placement and artistic stylisation in Makkah require further discussion.

- Universal Context: Hageneder [27] notes that trees, including palm trees, act as a link between earth and sky, representing humanity’s perpetual quest for spiritual transcendence. The palm tree embodies this aspiration with its upright form and upward-reaching fronds. Remarkably, its symbolism transcends cultural boundaries. In Christianity, for instance, the palm symbolises eternal life and victory, while in ancient Mesopotamian cultures, it signifies fertility and abundance. This cross-cultural resonance reinforces the universal nature of the palm tree archetype, yet comparative analyses between Makkah and other Islamic architectural traditions would further illuminate its local adaptation.

- Architectural Significance (The Palm Tree as a Living Symbol): In Makkah’s sacred architecture, the palm tree carries meanings beyond its physical form to represent higher spiritual ideals. The palm-inspired geometric designs in Islamic architecture showcase a remarkable balance between simplicity and precision, reflecting the quest for harmony between earth and sky. However, the extent to which these designs communicate spiritual meanings to contemporary viewers remains an open question. How has modern interpretation influenced the perception of these motifs?

- (b)

- The Role of Design in Amplifying Archetypal Symbolism

- (c)

- Representation in Makkah’s Decorative Motifs

- (d)

- Preservation of Archetypal Legacy

4.2.2. Pinecones: Symbols of Eternity and Stability

- (a)

- Archetypal and Symbolic Significance of Pinecones

- Eternity and Timelessness: Brown [28] explores how pinecones symbolise eternity in diverse cultural traditions. Their enduring and unchanging form makes them a natural representation of permanence and immortality, resonating with the archetypal desire for stability and continuity. In Makkah, these motifs may have been reinterpreted through an Islamic lens, aligning them with divine constancy and spiritual endurance concepts.

- Spiritual Resilience: Cooper [29] connects pinecones with spiritual resilience, suggesting they represent enduring faith and eternal values. These qualities align seamlessly with the Islamic emphasis on steadfastness and the pursuit of eternal reward. Further exploration of their integration into Makkah’s architectural compositions could provide insights into their evolving symbolic associations.

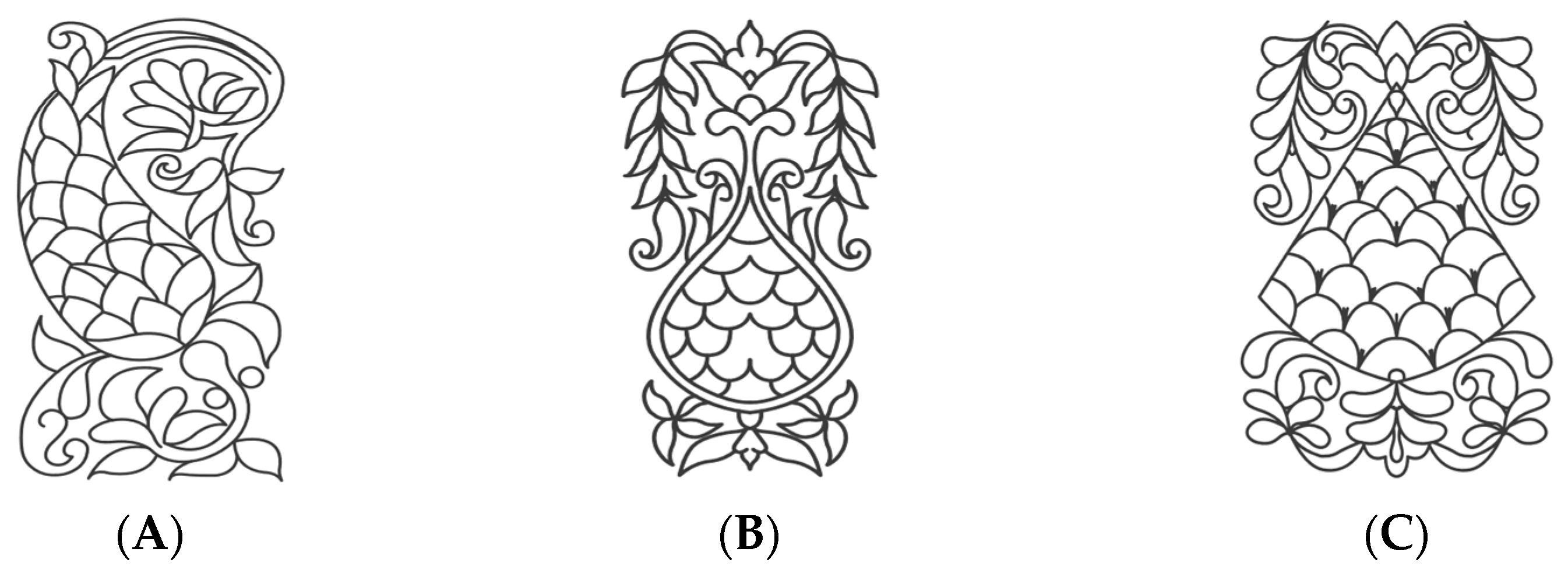

- (b)

- Representation in Makkah’s Decorative Art

- (c)

- Preserving the Archetypal Message

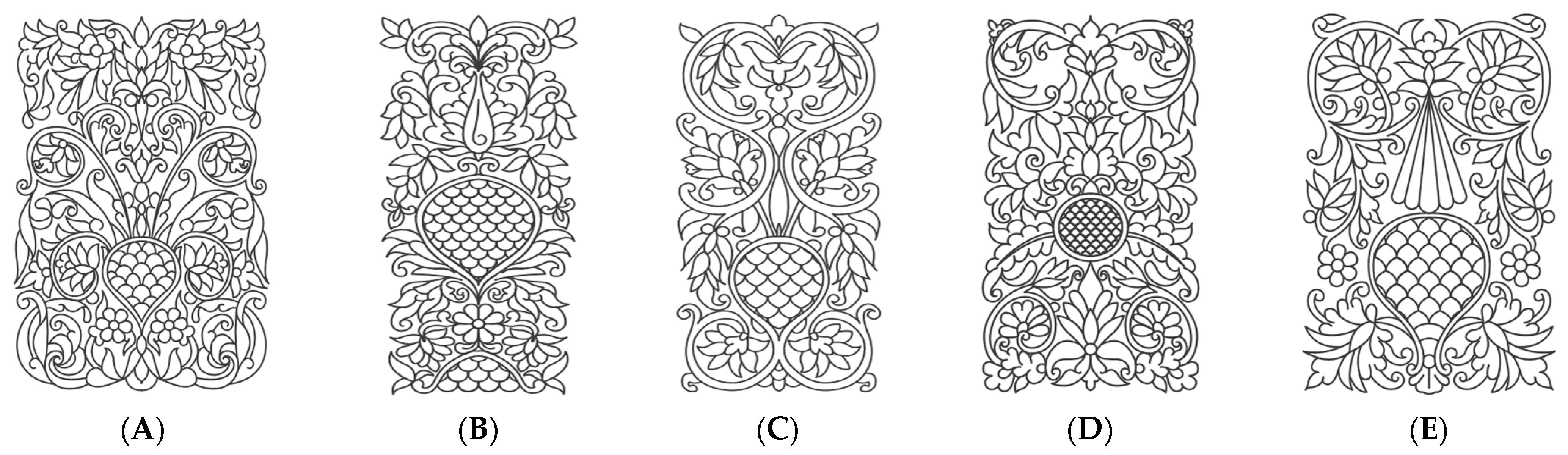

4.2.3. Interwoven Plants and Palm Fronds: Symbols of Life Cycles and Balance

- (a)

- Archetypal and Symbolic Significance

- Cyclical Renewal and Growth: Jung [30], in Man and His Symbols, explores the archetypal significance of natural motifs, such as interwoven plants, which remind the cyclical relationship between humanity and the divine. They represent the unending growth, decay, and renewal processes, underscoring life’s eternal balance.

- Sacred Continuity: Barfield [31] emphasises how plant imagery in art symbolises life’s continuity and its sacred interconnectedness with the natural world. This connection resonates with Islamic perspectives on the natural order as a reflection of divine grace.

- (b)

- Integration in Makkah’s Decorative Art

- (c)

- Combined Symbolism with Fish Scale Motifs

- Spiritual Nourishment and Renewal: Fish scales, symbolising sustenance and divine provision, complement the themes of regeneration and growth depicted by the plants.

- Harmonious Balance: Together, these elements create a narrative of cyclical balance, illustrating how divine grace sustains life’s natural and spiritual rhythms. This interplay reflects the integration of Islamic principles with the collective archetypal imagery found in Makkah’s art.

- (d)

- Cultural and Spiritual Legacy

4.2.4. The Combined Symbolism: Harmony Between the Divine and the Earthly

- Balance and Unity: Together, these motifs illustrate the harmony between spiritual grace and natural cycles, embodying the interconnectedness of all existence—a central theme in both Jungian theory and Islamic art.

4.2.5. Symbolic Heritage: Unity Between the Material and Spiritual

4.3. Analysis of Decorative Patterns According to Lamya Al-Faruqi’s Perspective and Principles of Islamic Art

4.3.1. Palm Trees: Symbols of Fertility and Spiritual Elevation

- Content Analysis

- Form Analysis

4.3.2. Pinecones: Symbols of Eternity and Stability

- Stylisation

- Non-Individuation

- Repetition

- General Form Analysis

4.3.3. Interwoven Plants and Palm Fronds: Symbols of Life Cycles and Balance

- Content Analysis

- Form Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison Between Carl Jung’s Theory of Collective Consciousness and Lamya Al-Faruqi’s Theory of Tawhid

5.2. Study Findings

5.3. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albarqawi, W. Makkah’s Urban Modernization and the Impact of Urban Regulations. J. City Dev. 2022, 4, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bagader, M.A. The Sustainable Investment in Urban Heritage Sites: Local, regional and international models. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, R.; Chabi, N. Heritage tourism in rural areas as a tool for sustainable local development in Jijel: A Case Study of El Ancer municipality. J. Manag. Econ. Res. 2024, 6, 470–488. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M.W.I.; Kamel, M.A.E. Strategy of Sustainable Conservation and Preservation to Stop Migration from Architectural Heritage Sites. Migr. Lett. 2023, 20, 1638–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, T. Art of Islam: Language and Meaning; World Wisdom, Inc.: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Faruqi, L.L. Islam and Art; National Hijra Council: Islamabad, Pakistan, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Çakıroğlu, B.; Akat, R.; Çakıroğlu, E.O.; Taşdemir, T. Semantic and Syntactic Dimensional Analysis of Rural Wooden Mosque Architecture in Borçka. Buildings 2025, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, S.H. Islamic Art and Spirituality; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aina, Y.A.; Al-Naser, A.; Garba, S.B. Towards an Integrative Theory Approach to Sustainable Urban Design in Saudi Arabia: The Value of GeoDesign. In Advances in Landscape Architecture; Özyavuz, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhi Nashalji, M.; Mehdizadeh Saradj, F. A Recognition Technique for the Generative Tessellations of Geometric Patterns in Islamic Architectural Ornaments; Case Study: Southern Iwan of the Grand Mosque of Varamin. Buildings 2024, 14, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, S.Z.A. Preserving Cultural, Social, and Architectural Heritage in Vision 2030; Al-Madina Newspaper Online Edition; Al-Madinah Press and Publishing Establishment: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan, Y.M.; Karban, A.S.; Hasanuddin, B.L.; Muhammad, B.A. Preservation of Islamic Urban Heritage to Enhance the Users’ Expection in the Holy City of Makkah. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism-ICCAUA, Alanya, Turkey, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, I.; Al Shomely, K.; Eltarabishi, F. Sustainability Implications of Utilising Islamic Geometric Patterns in Contemporary Designs, a Systematic Analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.T. A collective unconscious reconsidered: Jung’s archetypal imagination in the light of contemporary psychology and social science. J. Anal. Psychol. 2012, 57, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Kim, E. Archetype symbols and altered consciousness: A study of shamanic rituals in the context of Jungian psychology. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1379391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.H.; Ibrahim, Y.; Badaruddin, M.I. Malay and Islamic Traditions Elements Through the Paintings of Mastura Abdul Rahman, Ruzaika Omar Basareee and Haron Mokhtar. J. Arkeol. Malays. 2021, 34, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, M.H. The Transcendent Meanings of Islamic Architecture: A Philosophical Perspective on the Arts and Methods of Construction; Dar Al-Usul—Hadramout/Dar Al-Nour: Cairo, Egypt, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wikimedia Commons Mecca, Saudi Arabia Locator Map. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mecca,_Saudi_Arabia_locator_map.png (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Maps of World Makkah Map. Available online: https://www.mapsofworld.com/saudi-arabia/cities/makkah.html (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Al-Faruqi, I.R.; Al-Faruqi, L.L. Cultural Atlas of Islam; Macmillan: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harithi, N.A. Architectural Woodwork in the Hijaz During the Ottoman Era: An Artistic and Cultural Study; National Festival for Heritage and Culture, Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2002; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Mulu, R. Surprising Symbolism of Pinecones. In Symbolsage. 2023. Available online: https://symbolsage.com/surprising-symbolism-of-pinecones/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Divine Narratives Team. Pine Cone Symbolism in Ancient Cultures and Christianity. 2024. Available online: https://divinenarratives.org/pine-cone-symbolism-in-ancient-cultures-and-christianity/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hawting, G.R. The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hageneder, F. The Heritage of Trees: History, Culture and Wisdom; Brecourt Academic: Erie, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols. Ref. Rev. 1997, 11, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.C. An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.G. Man and His Symbols; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, O. The Rediscovery of Meaning: And Other Essays; Barfield Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, J. The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann, H. Dictionary of Symbolism: Cultural Icons and the Meanings Behind Them; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1968; Volume 9i. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinghausen, R.; Grabar, O.; Jenkins, M. Islamic Art and Architecture 650–1250; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Art and Architecture; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, J. Architectural Elements in Islamic Ornamentation: New Vision in Contemporary Islamic Art. Arts Des. Stud. 2014, 21, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Necipoğlu, G. The Topkapi scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinghausen, R.; Grabar, O. The Art and Architecture of Islam: 650–1250; Pelican History of Art 46; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S.S.; Bloom, J.M. The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Lamya Al-Faruqi | Carl Jung |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Islamic philosophy and (Tawhid) Tawhid (oneness of God)) | Psychology and psychoanalysis |

| Artistic Expression | Islamic art seeks to embody spiritual values rooted in Tawhid, emphasising divine unity over human-centred expression. | Symbols representing the collective unconscious |

| Ultimate Goal | Islamic art is not merely a medium for aesthetic expression but a philosophical and spiritual reflection that reinforces the idea that God is the sole Creator and that everything in the universe is interconnected through His unity. | Understanding psychological and social meanings |

| Symbolic Tools | Stylization ،Non-Individuation Repetition ،Arabesque | Archetypes (universal patterns) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, N.A.; Al-Ashwal, N.T. Reviving Architectural Ornaments in Makkah: Unveiling Their Symbolic, Cultural, and Spiritual Significance for Sustainable Heritage Preservation. Buildings 2025, 15, 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101681

Alghamdi NA, Al-Ashwal NT. Reviving Architectural Ornaments in Makkah: Unveiling Their Symbolic, Cultural, and Spiritual Significance for Sustainable Heritage Preservation. Buildings. 2025; 15(10):1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101681

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Nawal Abdulrahman, and Najib Taher Al-Ashwal. 2025. "Reviving Architectural Ornaments in Makkah: Unveiling Their Symbolic, Cultural, and Spiritual Significance for Sustainable Heritage Preservation" Buildings 15, no. 10: 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101681

APA StyleAlghamdi, N. A., & Al-Ashwal, N. T. (2025). Reviving Architectural Ornaments in Makkah: Unveiling Their Symbolic, Cultural, and Spiritual Significance for Sustainable Heritage Preservation. Buildings, 15(10), 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101681