1. Introduction

The AECO (architecture, engineering, construction, and operations) industry is undergoing a digital transformation [

1], which involves a comprehensive change process enabled by the innovative use of digital technologies [

2], where organizations integrate digital technologies into all aspects of their business. It has been described that digital transformation is not only about upgrading technology but also about developing ways of working, developing skills, and creating a culture that adapts to the digital age. Motivated goals for organizations to engage in digital transformation have been framed as improving business efficiency, creating new value, and meeting changing customer needs [

2,

3], making organizations more competitive, efficient, and adaptable in a rapidly changing world [

4]. The combination of BIM, machine learning, and data analytics can predict and prevent problems during construction, resulting in a more efficient and productive building process [

3]. Research suggests that the key to achieving digital transformation with the intended positive outcomes is the adoption of a systems approach to implement new technologies, including organizational support for individual employees to accept and learn to trust and use new technologies [

5]. To achieve this, previous research points to the importance of organizational change management, including providing clear goals, processes, and ways of working, but also creating a culture that integrates digital technology [

6,

7,

8]. In particular, leadership from a more human-centered perspective that encourages a holistic understanding of digital development and creates an organizational culture of trust is positively related to user acceptance and adoption of new technologies, such as BIM (building information modeling), robotics, and AI (artificial intelligence) [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Overall, leadership has emerged as one of the most important factors for successfully implementing digital work processes [

13,

14]. In this paper, we focus on trust-based leadership that promotes employee trust in and use of digital work systems.

1.1. Literature Review

There are established and common core leadership qualities that overall have been shown to promote trust and development in AECO organizations. These core leadership qualities include ensuring that employees have good development opportunities, effective work planning, and decisiveness, i.e., making timely and firm decisions, even under pressure and when dealing with conflict [

15,

16,

17]. Research has furthermore pointed out specific leadership traits that support a digital transformation. Haroon et al. [

18] point to the importance of leaders’ growth mindset, i.e., the ability to view failure as a learning experience, to believe that all people can develop their ability to do new things, to accept new challenges, to use feedback, and to provide timely feedback to subordinates.

Trust-based leadership is a leadership philosophy based on creating trust between leaders and employees and within different levels of the organization. Key characteristics of trust-based leadership include trust as a foundation, where the leader starts with a basic belief in the competence and willingness of employees to do their best; supportive leadership, where the leader acts as an enabler rather than a controller, focusing on removing barriers and supporting development; and long-term relationships, which last over time and focus on sustainable development rather than short-term results [

19,

20]. Transformational leadership is an example of a leadership style based on trust that has also been shown to promote the development and engagement of employees within a range of different sectors, including AECO organizations [

21]. At its core, transformational leadership relies on leaders who trust and strive to unleash the potential of their employees. By showing care, encouraging autonomy, and stimulating creativity, a culture of trust is created. Research also shows that transformational leadership is positively related to psychological safety and trust in work groups [

22]. Overall, the interplay between trust and leaders’ ability to promote role clarity appears to be important in digital transformation processes. Research suggests that clear definitions of roles and responsibilities, combined with strong management support, can increase trust, which in turn fosters effective collaboration and contributes to the success of digital initiatives [

9,

23,

24]. Examining employees’ perceptions of role clarity and how it interacts with trust in digital work systems in the AECO is therefore of interest. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies investigating this relationship within the industry.

In general, research suggests that leadership can promote learning and employee confidence in achieving goals through the ability to provide social support and empathize with people’s feelings when needed [

25], as well as foster open communication by speaking clearly, listening actively, and showing empathy, i.e., listening, helping, and supporting when problems arise [

26,

27,

28,

29]. As an example, according to Omer et al. [

14], pro-social behavior can be beneficial in managing construction teams that intend to implement BIM. Examples of such behavior could include a sense of concern and care for others, being open-minded and receptive to opinions, being tolerant and patient, and being understanding [

14]. Omer et al. [

14] conclude that such leadership strategies promote a constructive digital culture in construction projects, including followers who can better cope with stress and difficulties. Therefore, it is of interest to further explore interactions between social support from supervisor and employee trust in digital technology.

Leadership is also identified as a key factor in shaping a culture based on the trustful use of digital technology in the AECO industry, which is essential for the successful digitalization of an organization. A lack of trust is an obstacle for an organization that intends to adopt digital technologies and work systems [

14,

30,

31]. While digital tools and processes have the potential to transform project organization and execution, trust issues arise due to a lack of understanding and misinterpretation of the technology among team members. This can lead to mistrust and hinder project success [

32]. In contrast, an organization characterized by digital trust can foster innovation [

21,

33], facilitate team collaboration, and enhance the decision-making process during a construction project [

30]. In line with this, for successful digital transformation, Haroon et al. [

18] specifically mention honesty, humility, and courage as critical leadership behaviors.

In general, trustworthiness, ethical behavior [

34], and integrity are important leadership qualities that build trust and ensure that followers believe in the leader’s decisions and actions [

35]. The development of employees’ trust in and willingness to adopt new digital work systems can also be seen as a dynamic process in which a general and reciprocal climate of trust and support between leaders and employees creates psychological safety, which in turn can promote innovation and adaptation to new ways of working in knowledge-intensive sectors [

36]. Vertical trust is defined in this paper as trust between leaders and employees within an organization, including mutual norms of social reciprocity and recognition, which research has shown to promote engagement in developmental work [

37] and innovation within a work organization [

38]. While trust is partially addressed in studies on leadership, technology use, and organizational behavior [

12,

39,

40,

41], there is a gap in research focusing on the specific interaction between vertical trust and trustful use of digital work systems in the AECO industry.

Moreover, leadership in digitally transforming organizations appears to require additional characteristics beyond traditional leadership characteristics [

21]. Although many core leadership skills remain the same, the unique demands of digital disruption also require some new skills [

4]. The management team needs digital literacy, i.e., the necessary competencies to implement a digital strategy and digital development, and these competencies include specific behaviors and characteristics rather than just technical skills and a business orientation [

21].

1.2. Scope and Aim of This Study

In summary, the AECO industry is currently undergoing a digital transformation, and research shows that leadership and trust are important factors for successful digital transformation. There are indications that certain leadership qualities can promote trustful use of digital work systems; however, there is limited research on what these specific characteristics are. Therefore, building on trust-based leadership, it is of interest to investigate which aspects of leadership specifically promote the trustful use of digital technologies. The purpose of this study was to identify which aspects of leadership are of most importance for trustful use of digital work systems in the AECO industry. To achieve the objectives of this study, the following research questions were addressed:

RQ1 Which leadership aspects (digital literacy of the management team, general leadership qualities, vertical trust, role clarity, and social support from supervisor) are associated with employees’ trust in and use of digital work systems?

RQ2 Which leadership aspect has the strongest association with employees’ trust and use in digital work systems?

RQ3 Are there differences between groups of experts in their use and trust of digital work systems?

2. Materials and Methods

A quantitative research design was applied, including an online questionnaire survey targeting employees in the construction industry. The use of quantitative methods and closed-ended questionnaires has proved effective in gathering structured data and providing nuanced insights in a variety of research areas [

42].

2.1. Context and Participants

A single-stage sampling method was used for this study. Participants were employed in the same department at Sweden’s largest infrastructure owner, the Swedish Transport Administration (STA), and had expertise in one of five different areas: construction, design, digital information management, environment, or technical systems. This selection of groups was considered valuable for this study because the organization is currently in the preliminary stages of adopting building information modeling (BIM), artificial intelligence (AI), and automation. In addition, these professionals are expected to incorporate digital work practices into their routine tasks in the near future.

The organization was selected for its significant role in establishing standards within the Swedish construction industry. Due to its considerable size and complex nature, this organization encapsulates a wide range of viewpoints on digital advancements and applications within the Swedish construction industry. In addition, the experts involved in this research came from different professional fields, each bringing unique experiences, methodologies, and levels of proficiency in the use of digital work.

2.2. Data Collection

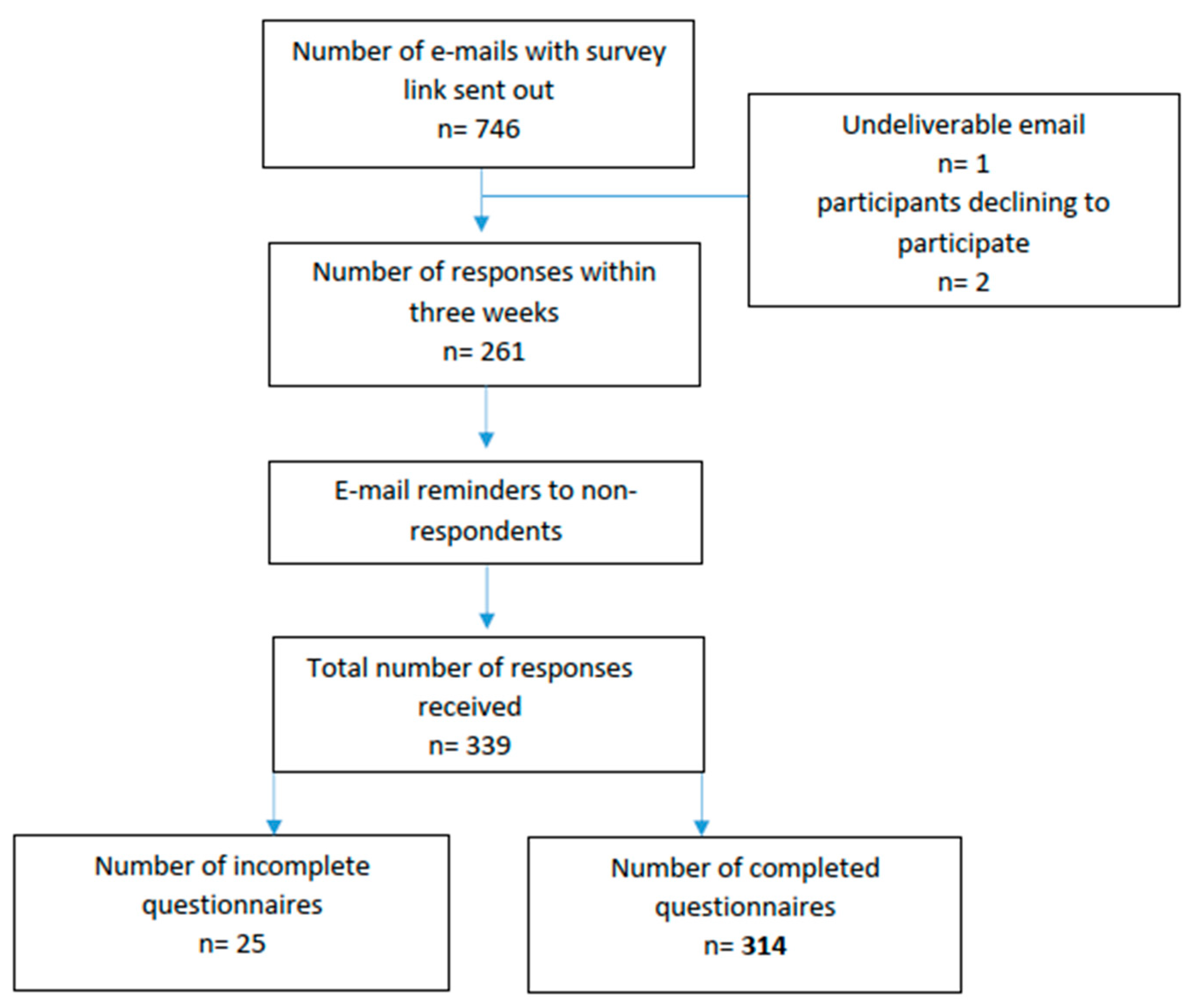

A total of 746 individuals received an email with a link to an online survey. Of the 339 responses received, 25 were identified as incomplete, resulting in 314 valid responses for analysis; see

Figure 1 for the data collection process.

Table 1 shows the distribution of invited experts along with the number of respondents within each expert category. The questionnaire was developed and administered using SurveyMonkey following the data collection methodology outlined by Creswell and Creswell [

43]. The first communication consisted of a brief pre-announcement, which was sent to all participants by the department heads. The second email contained both the formal invitation and the survey link. Three weeks later, a reminder email was sent to all individuals who had not yet responded.

The invitation was sent to 746 individuals, with one email returned as undeliverable and two participants declining to participate. A total of 314 responses were collected, resulting in a response rate of 42%. A detailed description of the sample is provided in

Table 2.

2.3. Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Board (2023-03239-01) prior to initiating this study and distributing the questionnaires. In addition to the e-mail correspondence, participants received an information sheet detailing the objectives of this study, the handling of personal data, and the voluntary nature of their participation. Consent was implied by the completion and submission of the questionnaire, with the option to withdraw at any time without giving reasons. To ensure confidentiality for the analysis, each respondent was assigned a personal code. The code list, including personal information, is locked in a secure storage at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in Stockholm to ensure that no unauthorized person can access it, and it will be destroyed 10 years after the survey is completed.

2.4. Questionnaire

A questionnaire survey with approximately 40 questions covering a range of topics related to digital transformation, digital work systems, and organizational and social factors, including leadership was sent to the study population in November 2023. For a complete presentation of the survey questions, see

Appendix A. The outcome variable was formulated as a single statement—I trust and use our digital work systems—to examine overall trust in digital work systems within the organization. A single statement was also chosen to measure the first explanatory variable—Our management team has the necessary skills to implement a digital strategy and develop a digital business—in order to obtain an idea of how respondents perceived the digital literacy of the management team. To our knowledge, there are no instruments that measure these factors (trustful use of digital work systems and digital literacy of the management team). However, as these are factors that have been identified as important for trust in digital work systems, we decided to formulate single questions to measure these factors. The 5-point Likert scale consisting of the following items was used for the answers of the single items: (1) to a very small extent; (2) to a small extent; (3) somewhat; (4) to a large extent; and (5) to a very large extent.

The questionnaire included four indices from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III) that were selected as explanatory variables: role clarity (the extent to which there are clear objectives, responsibilities, and expectations for the individual role),

vertical trust (perceived trust between leaders and employees),

social support from managers (perceived help and support from superiors when needed), and

leadership quality (how well supervisors plan work, resolve conflicts, and provide development opportunities). COPSOQ III has been extensively utilized across various studies in a variety of sectors [

44,

45] to assess psychosocial work factors, job satisfaction, and related psychosocial risks. COPSOQ III provides reliable and distinct measures of a wide range of psychosocial dimensions of modern working life [

46]. The Swedish validated version of COPSOQ III used in this study is shown to have good psychometric properties for its intended use [

47]. The 5-point Likert scale was used for the answers to the COSSOQ questions, consisting of the following items: (1) strongly disagree; (2) disagree; (3) neither agree nor disagree; (4) agree; (5) and strongly agree. See

Table 3 for questions.

Cronbach’s alpha was tested for all indices. The number and percentage of valid responses, as well as Cronbach’s alpha and the number of questions per index, are shown in

Table 4.

2.5. Analysis

A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to determine the variables significantly associated with trustful use of digital work systems. Backward elimination was chosen over forward selection for its reliability in jointly identifying significant predictors, its ability to provide a transparent and interpretable model, and its role in reducing the risk of overfitting [

48,

49].

A threshold

p-value of less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. Before the regression analysis, normal distribution and multicollinearity assessments were performed for each variable. First, a correlation analysis was performed to analyze the associations between the explanatory variables (i.e., the indices) and the outcome (trust in digital work systems), as shown in

Table 5. A backward elimination procedure was then applied within the framework of multiple linear regression. In the initial model (Model 1,

Table 6), variables with significant correlations were included. Variables were systematically removed until the remaining variables reached statistical significance.

To explore additional factors associated with trustful use of digital work systems, potential confounding variables, such as age, gender, experience with current tasks, experience with digital work systems, and expert area, were controlled for. Finally, to further analyze whether there were any differences between different groups of employees, ANOVA tests were conducted on differences in mean ratings for trustful use of digital work systems.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate which aspects of leadership (digital literacy of the management team, general leadership qualities, vertical trust, role clarity, and social support from supervisor) are associated with the outcome of trustful use of digital work systems. Previous studies have examined the importance of leadership for digital transformation in general and the trustful use of digital work systems specifically, but to our knowledge, no study has focused on which leadership characteristics are of most importance for the trustful use of digital work systems in the construction industry. All variables showed unilateral correlations with the outcome, while the results from the multiple linear regression analysis in this study showed that digital literacy of the management team and role clarity were statistically significantly associated with the outcome, while vertical trust, social support from supervisor, and leadership quality were not. None of the potential confounders controlled for (age, gender, area of expertise, experience with current tasks, and experience with digital work systems) were found to have any influence on the associations between trustful use of digital work systems and explanatory variables (digital literacy of the management team and role clarity).

Vertical trust (perceived trust between leaders and employees), social support from managers (perceived help and support from superiors when needed), and leadership quality (how well supervisors plan work, resolve conflicts, and provide development opportunities) only showed significant associations with trustful use of digital work systems in the unilateral correlations. While these aspects of leadership are generally essential factors for trust within organizations, our findings suggest that other additional leadership aspects accompany trust during digital transformation. None of these factors showed statistical significance in the regression models (Models 1–3). The reason for this may be that in a project organization such as STA, experts are rarely supervised by their line manager, and decisions regarding the use of digital work systems and digital work methods are made by the project manager of the project in which the experts do their daily work. This, in turn, may mean that the digital literacy of the project management team has a greater impact on trust, while the role of the line manager becomes purely administrative. This organizational structure may be perceived as fragmented and unclear, and clarity of one’s role, for example, may seem more important than other factors.

Several leadership qualities have been identified in previous research as beneficial for successful digital transformation, for example, a change-oriented mindset [

4] and forward-looking, experimental, and innovative thinking [

50]. In addition to these future-oriented characteristics, softer characteristics, such as transparent communication, tolerance, engagement, being ethical, trust-building, inspiring, self-awareness, and role modeling [

14,

21,

51,

52,

53,

54], are also beneficial. This study contributes to the list of important leadership characteristics by highlighting the importance of the ability to develop role clarity and digital literacy of the management team. Depending on the context, certain traits may be more important in building trust in digital technologies; however, in this study, we focus on which specific leadership characteristics may contribute to employee trust in the use of digital work systems in the AECO industry.

Previous research identified role clarity as critical to building trust in professional settings, as it reduces uncertainty and increases commitment and innovativeness. The connection between role clarity and trust emphasizes the necessity for organizations to establish clear roles to cultivate a trustful environment within the workplace [

55,

56,

57]. As the results of our study show, role clarity is also an important factor in the development of trust in digital tools. By providing users with a transparent understanding of their responsibilities and the capabilities of the tools at their disposal, role clarity can increase user trust and participation in digital environments and capability to adapt [

58,

59,

60]. Role clarity was the factor that was consistently found to be most strongly associated with trustful use of digital work systems in this study, and the results suggest that addressing issues around clear role descriptions and ensuring that employees understand their responsibilities can significantly improve the industry’s ability to adapt to digital transformation. This suggests the importance for large and complex organizations of clarifying digital strategies and goals, as well as the responsibilities associated with different roles, as more digital work systems are implemented.

In line with Khamiliyah et al. [

61], the results of this study suggest that the digital literacy of management teams is essential for fostering a culture of trust in the context of digital transformation initiatives. The results may be explained by the fact that the perception that the management team does not have the necessary skills also implies distrust in management’s strategies for digitalization, including distrust in the digital work systems chosen by the organization. Furthermore, members of the management team can also be seen as important role models [

21] for leading the way in the use of digital work systems, and digital literacy can be seen as an important aspect of being able to be such a role model.

The findings of this study reinforce the importance of trust-based leadership as a key driver of digital transformation in the AECO industry. This study more specifically contributes to knowledge on critical aspects of such leadership, including a focus on clarifying roles and manifesting competence. The results are in line with previous research that points out that clarifying roles reduces uncertainty and fosters psychological safety [

22], while leaders’ digital competence builds trust in both leadership and new technologies [

21,

36]. These factors function not only as leadership skills but also as mechanisms for establishing trust during digital change. The results of our study suggest that organizations should prioritize leadership development that promotes role clarity and strengthens digital competence to support the adoption of digital work systems. Although conducted in a Swedish context, these findings are broadly applicable across national, cultural, and institutional settings undergoing digital transformation. Role clarity and digital literacy are universal leadership principles that can stabilize organizations, reduce uncertainty, and foster trust, particularly in hierarchical or complex environments facing rapid technological change. In less digitally mature contexts, this may require targeted capacity building, while in more advanced settings, it involves strategic skills such as data interpretation and managing cross-functional teams. While specific conditions may influence the extent of their impact, role clarity and digital literacy consistently emerge as foundational strategies for building trust in digital transformation processes.

By creating an environment that fosters digital skills and knowledge in management teams, organizations appear to be able to increase employee trust and thus facilitate the adoption and use of digital work systems. Just as employees need development opportunities and training in new digital work systems, it may be necessary to improve the digital skills of management teams, for example, through targeted training, fostering a culture of continuous learning, and maintaining the adaptability of training strategies.

Method Discussion

The survey is largely based on indices from a validated survey instrument. However, there are two single-item questions included. The use of single-item measures for trustful use of digital work systems and digital literacy of the management team has both advantages and disadvantages. As Allen et al. [

62] point out, arguments against single-item measures include that the reliability of single-item measures is simply unknown in most cases. On the other hand, they can be beneficial by reducing respondent effort and thus respondent frustration [

62], which in turn should promote reliability. According to Bergkvist and Rossiter [

63], the predictive validity between multiple- and single-item measures is equivalent.

To be noted is that the analysis models explained the variance of the outcome to a more limited extent (r

2 = 0.23–0.27), which suggests that there are other explanatory factors in addition to this study’s included leadership characteristics that are important for the outcomes. For example, factors such as perceived value of digitization, user attitudes, usability of digital work systems, and communication and collaboration within construction project teams could also influence trustful use of digital work systems [

5].

The response rate of 42% can be considered low but still normal for online surveys. According to Wu et al. [

64], the typical response rate for online surveys is around 44.1%. Although the survey was conducted within one organization, the results can still be considered representative due to STA being a large and complex organization that includes experts with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and areas of work.

5. Conclusions

This study examined leadership characteristics that benefit organizations in the AECO industry undergoing digital transformation. Specifically, it addressed characteristics associated with trustful use of digital work systems and identified gaps in existing knowledge about trust-based leadership in digital transformation.

The findings showed that role clarity and digital literacy of the management team were the two leadership aspects most strongly associated with trustful use of digital work systems. Of the dimensions examined, role clarity emerged as the strongest factor. Hence, the results indicate that clearly defined roles and responsibilities reduce uncertainty, promote engagement, and foster trust, particularly in complex digital transformation processes. Digital literacy of the management team was also a significant explanatory factor. The results thus imply that leaders with digital competence can act as credible role models, guiding employees through change and building confidence in new technologies.

No significant differences were found between employee groups, suggesting that these leadership principles apply broadly across diverse roles and demographics in the sector. From a trust-based leadership perspective, these results underscore that building trust in digital transformation requires more than general leadership behaviors; it seems to demand structural clarity and leadership competence in digital domains.

These findings provide clear steps to take for organizations navigating digital transformation. First, management teams at all levels should receive targeted training to develop digital leadership skills. Second, organizations should prioritize clarifying roles and responsibilities related to new digital processes, especially in complex and evolving environments. These trust-based leadership measures will create the clarity and competence needed to strengthen employee trust and accelerate the adoption of digital work systems. Institutionalizing these practices will enhance both the human and technological dimensions of digital transformation.

This study focused primarily on the perspective of experts on trust in digital transformation. However, there is room for future research to include leaders’ perspectives to explore their potential as role models in the digitalization of work.