Reimagining the High-Density, Vertical 15-Minute City

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives and Methodology

2. Overview of 15-Minute City

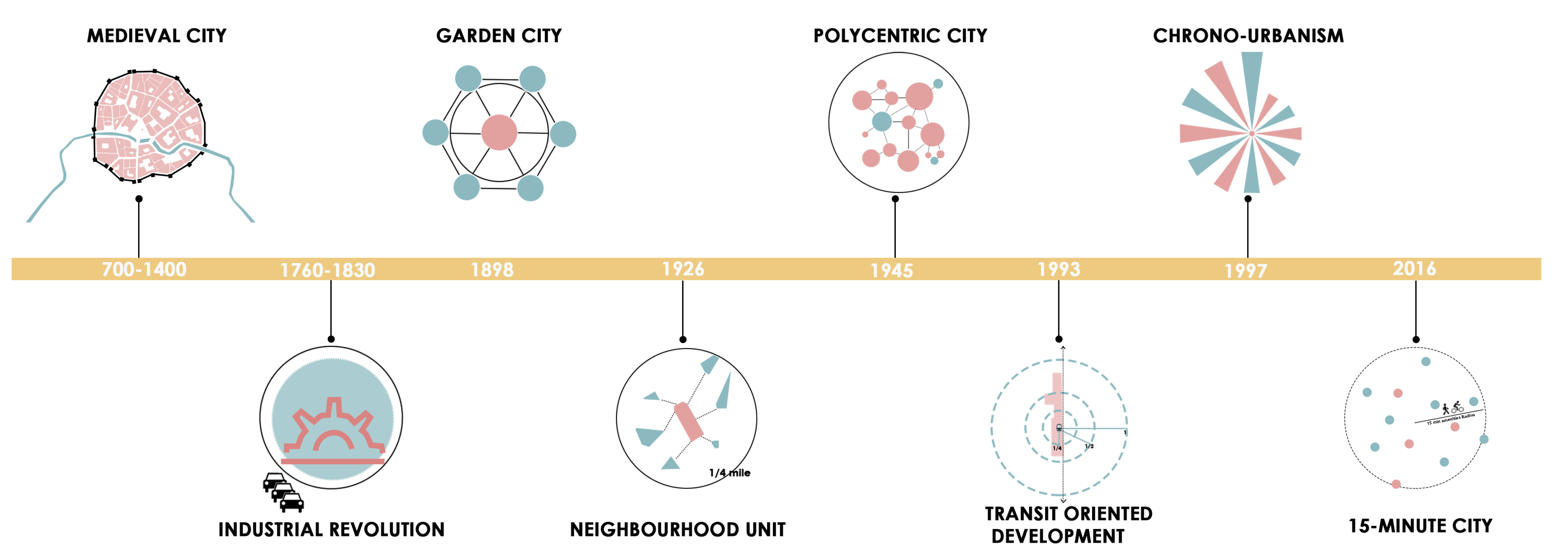

2.1. Historical Development of Cities

2.2. Implementation of the 15-Minute City in Global Cities

2.3. Transport and Mobility Within a 15-Minute City

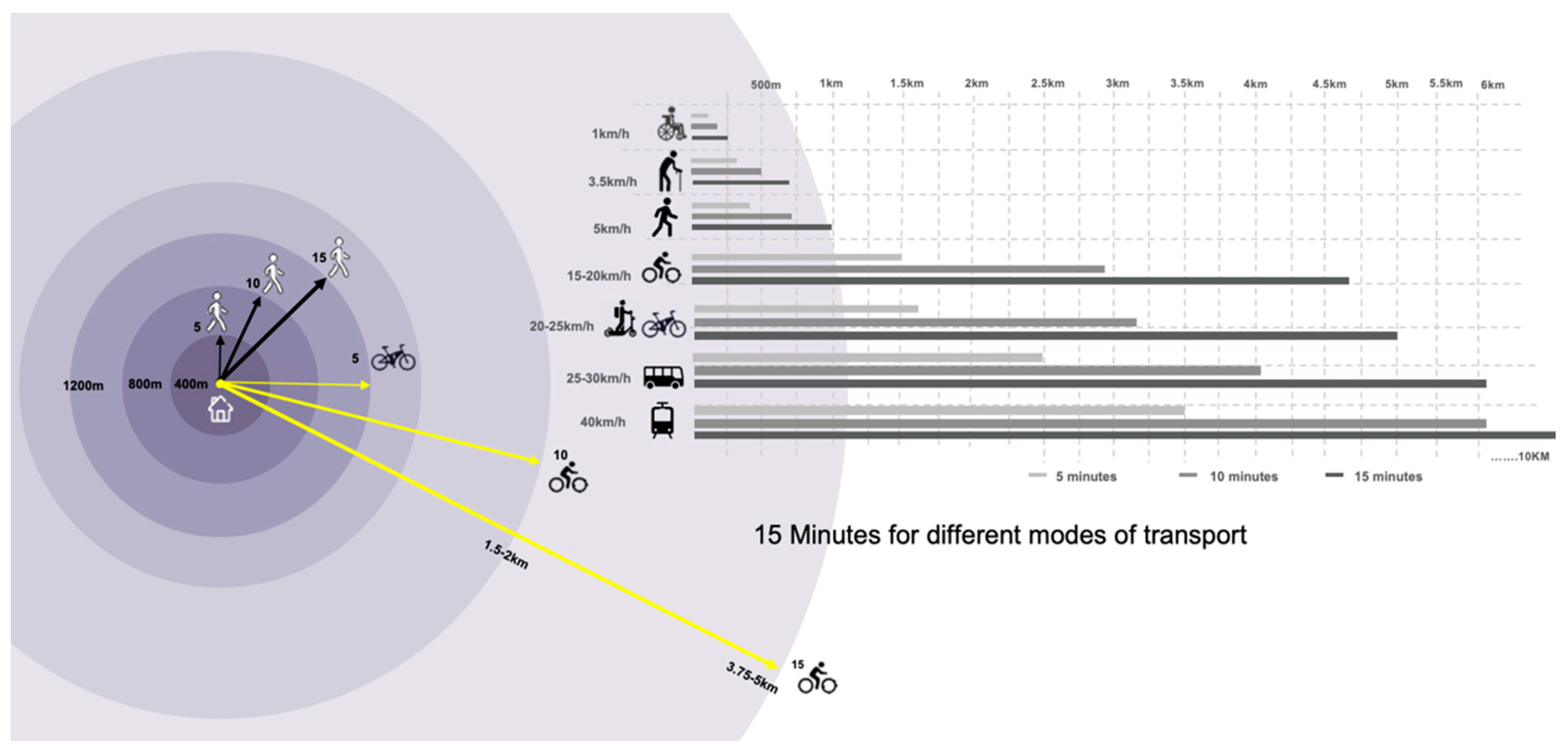

2.3.1. Multimodal Catchments: Active Transport and Public Transit Modes

- Slow walking/assistive devices (≈1 km h−1) extend the 15-minute catchment to ~250 m, highlighting the importance of barrier-free design for the very young, elderly, or mobility-impaired.

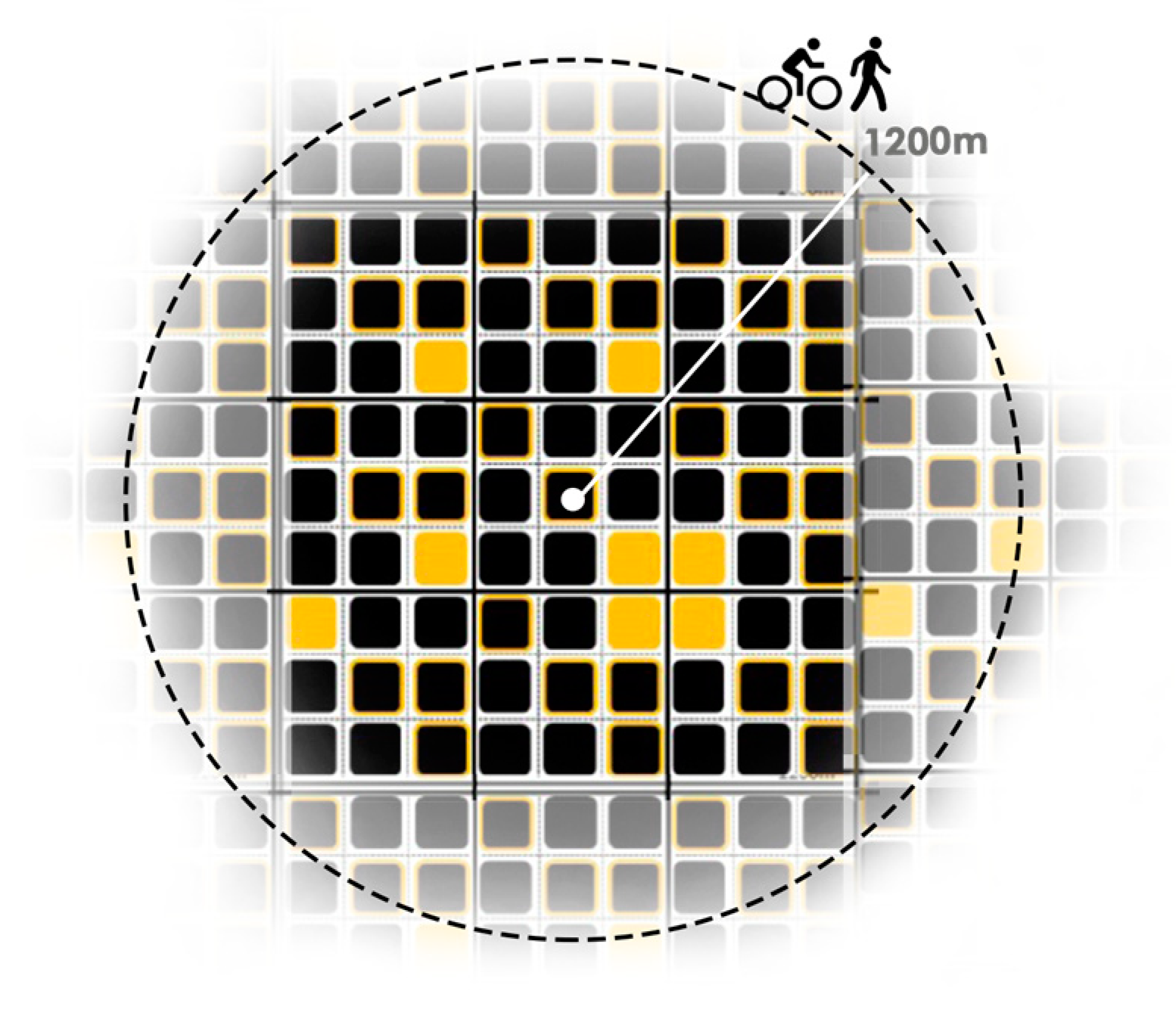

- Typical walking (3.5–5 km h−1) expands the radius to 1.0–1.2 km.

- Cycling and e-bikes (15–25 km h−1) push the reachable area out to 3.7–5 km.

- Neighborhood buses or LRT (25–40 km h−1) stretch the 15-minute horizon to 6–10 km, effectively linking multiple 15-minute neighborhoods.

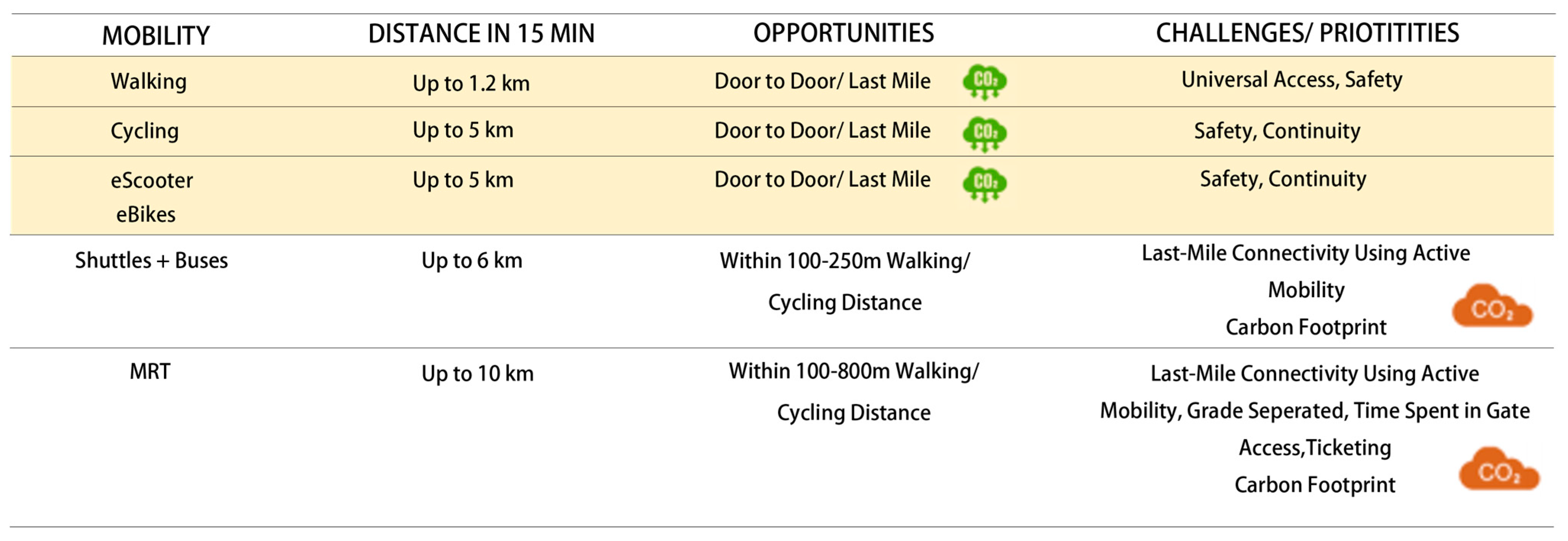

2.3.2. Recommended Mobility Systems Within 15-Minute City

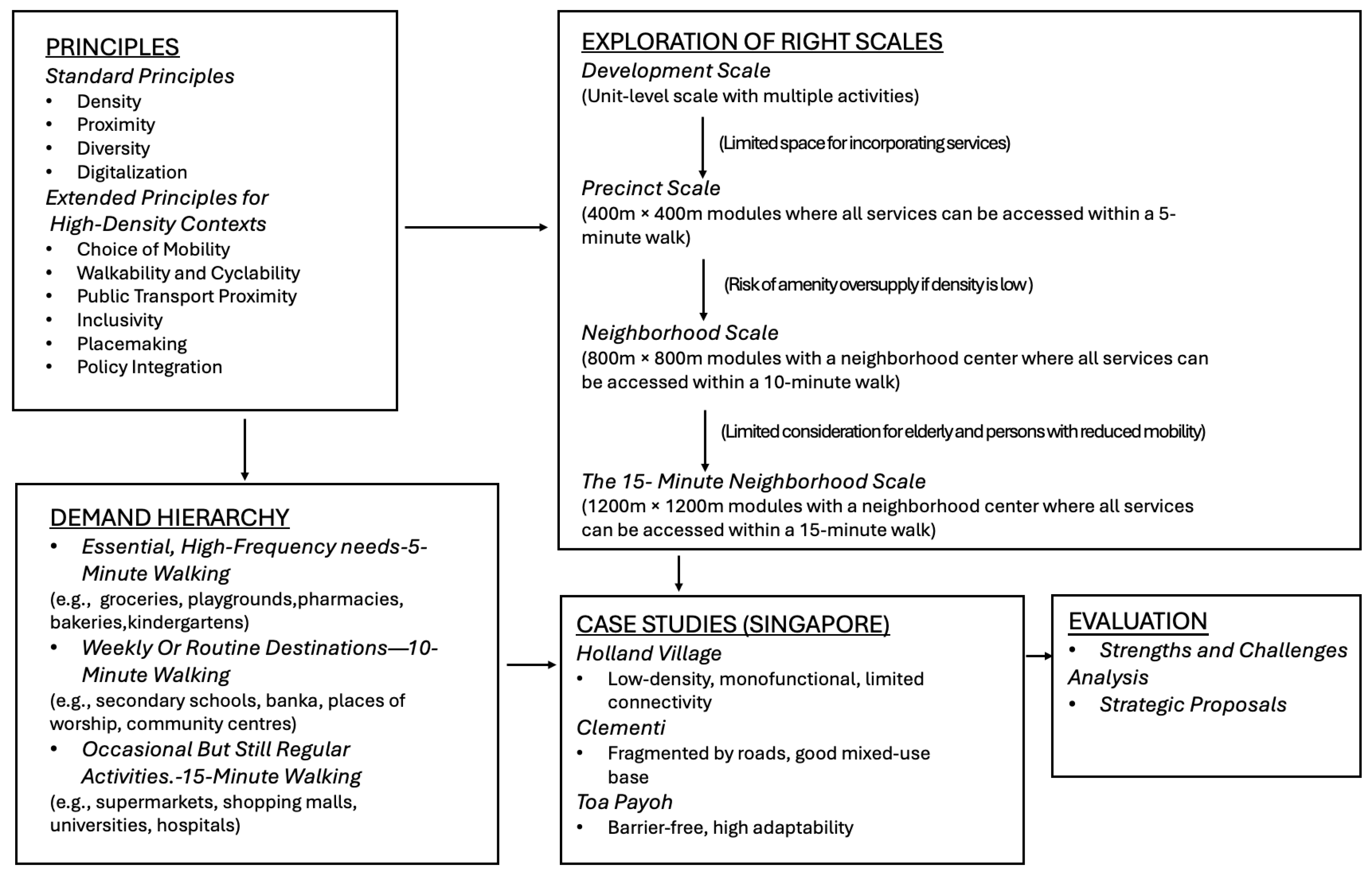

3. Methodology: Making 15-Minute Cities

3.1. The Key Principles of 15-Minute Cities

3.1.1. Essential Principles in 15-Minute City Frameworks

- Density

- 2.

- Proximity

- 3.

- Diversity

- 4.

- Digitalization

3.1.2. Toward a New Scalable Framework for High-Density Cities

- Choice of Mobility

- 2.

- Walk and Cyclability

- 3.

- Proximity to Public Transport

- 4.

- Inclusivity

- 5.

- Placemaking

- 6.

- Policy

3.2. The Scale of 15-Minute Cities

3.3. A Hierarchical Framework: 15-Minute City

3.4. Form of the 15-Minute Neighborhood: The Spatial Model

4. Case Study—Applying the Framework to Three Singapore Neighborhoods

Comparison of Neighborhood Adaptability

5. Results and Discussions

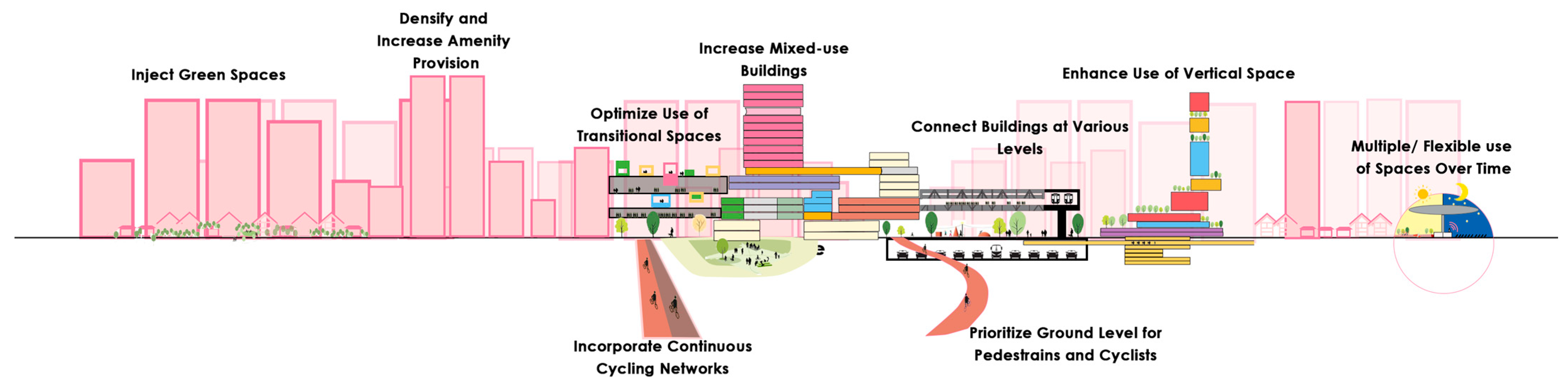

5.1. Fifteen-Minute City: Proposed Strategies

5.1.1. Mobility and Connectivity

Multilayered Mobility Network

Seamless Vertical–Horizontal Connectivity

5.1.2. Inclusivity and Comfort

Barrier-Free and Inclusive Design

Encouraging Sustainable Behavior

5.1.3. Mixed-Use and Vertical Development

Multifunctional Vertical Integration

Vertical Integration of Green and Public Spaces

5.1.4. Time-Based Flexible Planning

Chrono-Urbanism Application

6. Conclusions: Towards a New 15-Minute City Future

Limitations and Future Research

7. Glossary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Escorcia Hernández, J.R.; Torabi Moghadam, S.; Sharifi, A.; Lombardi, P. Cities in the Times of COVID-19: Trends, Impacts, and Challenges for Urban Sustainability and Resilience. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 432, 139735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Su, Z.; Jin, R.; Dawodu, A.; Sedrez, M.; Pourroostaei Ardakani, S.; Zou, T. Space and Social Distancing in Managing and Preventing COVID-19 Community Spread: An Overview. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realdania. The 15-Minute City: International Experiences; Realdania: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The 15-Minute City Represents Sustainable Urban Living; Winssolutions: Bahçelievler, Turkey, 2025.

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-Minute City Lens: Mapping the Accessibility and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, W. The 8 Largest Cities of the Medieval World; TheCollector: Montreal, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.C. The Industrial Revolution: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-870678-6. [Google Scholar]

- Garden City Concept (1898–1902) by Ebenezer Howard: A Pioneering Vision in Conceptual Urban Planning Theories; Rethinking The Future: Delhi, India, 2022.

- Neighbourhood Unit; Wikipedia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024.

- Harris, C.D.; Ullman, E.L. The Nature of Cities. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 1945, 242, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraeva, A.; Correia, G.H.d.A.; Silva, C.; Antunes, A.P. Transit-Oriented Development: A Review of Research Achievements and Challenges. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, R.; Ira, V.; Trojan, J. A Tale of Two Cities: The Comparative Chrono-Urbanism of Brno and Bratislava Public Transport Systems. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2020, 28, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiazdzinski, L.; Maggioli, M.; Straw, W. Geographies of the Night. From Geographical Object to Night Studies. Boll. Della Soc. Geogr. Ital. 2018, 14, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Krier, L. Architecture: Choice or Fate; Andreas Papadakis Pub: Windsor, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-1-901092-03-5. [Google Scholar]

- DPZ CoDesign. Seaside, Florida; DPZ CoDesign: Miami, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Gehl, J.; Thorne, M. The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-394-22814-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gongadze, S.; Maassen, A. Paris’ Vision for a ‘15-Minute City’ Sparks a Global Movement; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. Benchmark: 15-Minute Cities; C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. C40 Knowledge Hub Why Every City Can Benefit from a ‘15-Minute City’ Vision; C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Authority, Land Transport. Land Transport Authority Land Transport Master Plan 2040; Land Transport Authority (LTA): Singapore, 2023.

- Duany, A.; Steuteville, R. Defining the 15-Minute City; CNU: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-Minute City: Urban Planning and Design Efforts toward Creating Sustainable Neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Y. More S’pore Residents Take Trains and Buses to Work, Fewer Drive to the Office: Population Census; Straits Times: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Land Transport Authority LTA|An Inclusive Public Transport System. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/getting_around/public_transport/a_better_public_transport_experience/an_inclusive_public_transport_system.html (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Wangchuk, T. Clarence A Perry’s Concept of a Neighborhood Unit; Planning Tank: Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ayllón, S.; Miralles García, J.L. Sustainable Urban Planning & Territorial Management: Future challenges in a world in transition. In Proceedings of the SUPTM 2024 Conference; Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena: Cartagena, Colombia, 2024; ISBN 978-84-17853-82-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Solá, A.; Vilhelmson, B. Negotiating Proximity in Sustainable Urban Planning: A Swedish Case. Sustainability 2019, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETX Studio. What Is “Chrono-Urbanism”? Malay Mail: Selangor, Malaysia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akristiniy, V.A.; Boriskina, Y.I. Vertical Cities—The New Form of High-Rise Construction Evolution. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 33, 01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOHA. Pan Pacific Orchard Hotel/WOHA; WOHA: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

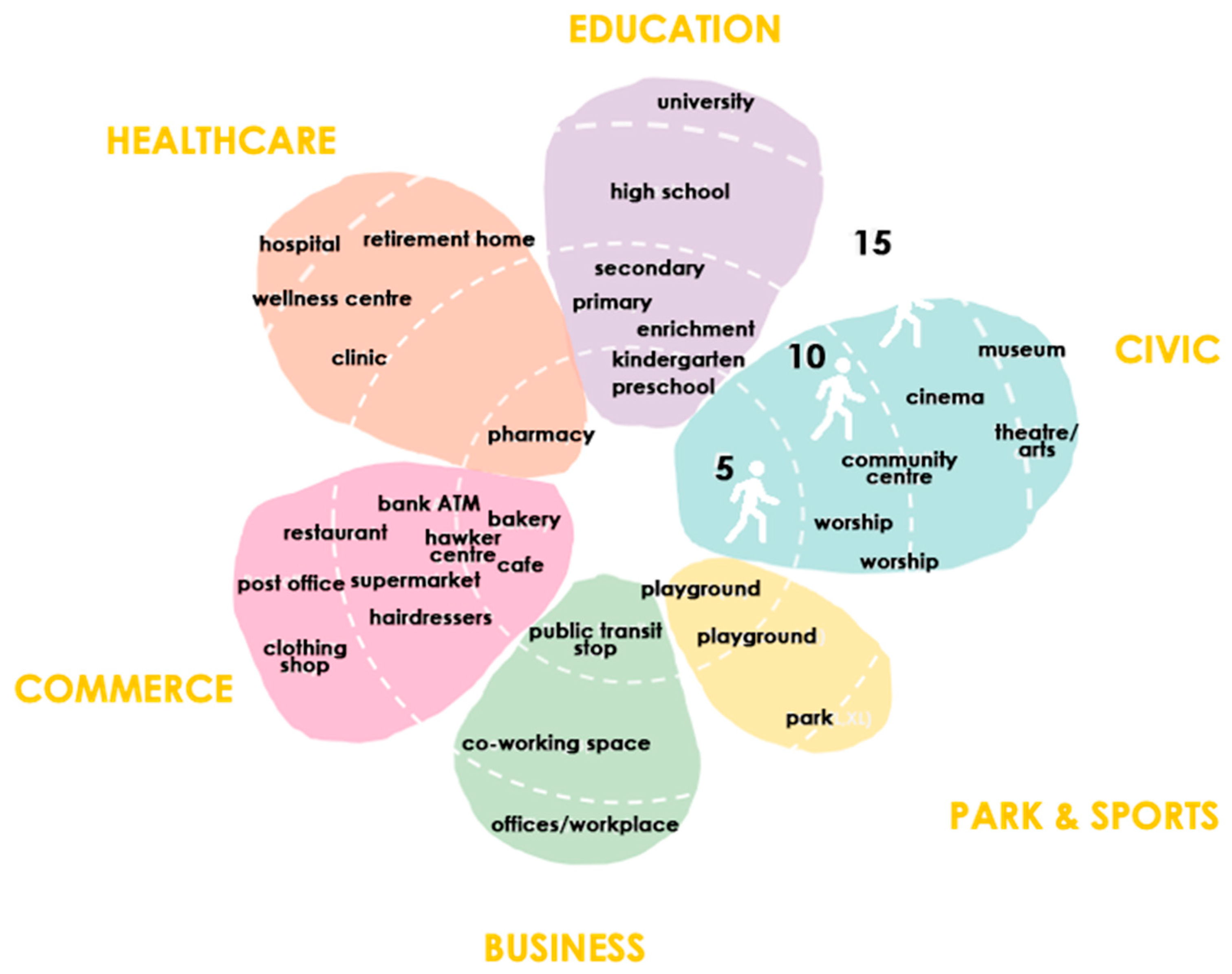

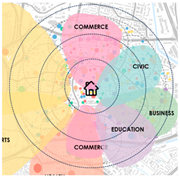

| Proximity to essential services: Distribution of daily need and essential services within 15 min walking and cycling distance of all residents. This eliminates the need to travel far from home to access amenities/services, reducing traffic on the roads and increasing car-independent mobility within neighborhoods. |

| Choice of mobility (new): Walking and cycling are considered as the key mode of transportation for the movement of people within the 15-minute city. Given the different speeds of the various modes of transport, one can cover a greater distance in 15 min by using faster means of active transportation, e.g., electric bike or e-scooter. |

| Proximity to public transport (new): For the residents to access city-level amenities, services, and businesses, e.g., higher education, specialty hospitals, and offices planned outside the neighborhood without relying on a car. Local public transport may also be considered as an additional mode of transport, especially for people with reduced mobility. For example, significant enhancements to the transport infrastructure, including transit priority corridors and the continued expansion of the rail network, have been instrumental in encouraging more people to commute to work via public transport in Singapore [24]. |

| Walk and cyclability (new): The safety of pedestrians and cyclists is another important aspect. Wide, well-connected, unobstructed, and continuous walking and cycling pathways. Wider pedestrian crossings for safety through improved road junction design. Secure bicycle parking and storage arrangements. Well-shaded and sheltered areas ensuring comfort. Seating areas along pedestrian pathways for rest and meet and greet fellow residents that increase community engagement and improve the neighborhood’s sense of safety positively. |

| Inclusivity (new): Universal design and mobility options for people with mobility impairments including the provision of wheelchairs and other mobility aids. For instance, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) in Singapore has implemented extensive barrier-free access across its public transport network. This includes allowing open strollers, wheelchairs, and other Personal Mobility Aids (PMAs) such as mobility scooters on buses and MRT/LRT trains [25]. |

| Density: The population and employment density of a neighborhood should be able to support the existence of local businesses, amenities, and services that are essential for a self-sufficient neighborhood. Medium-to-high-density neighborhoods could support vibrant mix of uses and amenities. |

| Diversity and Flexibility: A variety of uses and amenities within the neighborhood fulfill daily needs of the residents. Transient uses can be planned to meet short-term or intermediate demand for amenities within a neighborhood. |

| Placemaking (new): Creating public space and incorporating amenities through community participation and to support active community engagement. Improve comfort of residents for walking and cycling through improved urban design and streetscape design, enhancing residents’ quality of life and improving their physical and mental health. |

| Digitalization and innovation: Integrate use of diverse and advanced technologies to collect and analyze data for demand-based planning of essential services. Technology and innovation to support access to remote services without adding traffic to the road, e.g., remote working, online shopping. On demand/mobile services, popup amenities to provide essential services at doorstep. |

| Policy (new): It is key to incentivizing and bringing positive behavioral changes towards walking and cycling. Policies can facilitate flexible land and building use to allow for improved provision of and access to urban amenities and social infrastructure, e.g., school yards for public use after school hours and weekends, access to roof top green for community gardens, and adaptable street design to plan amenities within proximity of homes. |

| Scale | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Development Scale | ||

| During the pandemic, our homes formed the place for multiple activities during different times of the day, e.g., daily living, work, exercise, and other recreation. Digital technology was used to access essential services leading to less traffic on the roads and improved air quality. | The key challenge is incorporating services at building/development scale |

| Precinct Scale | ||

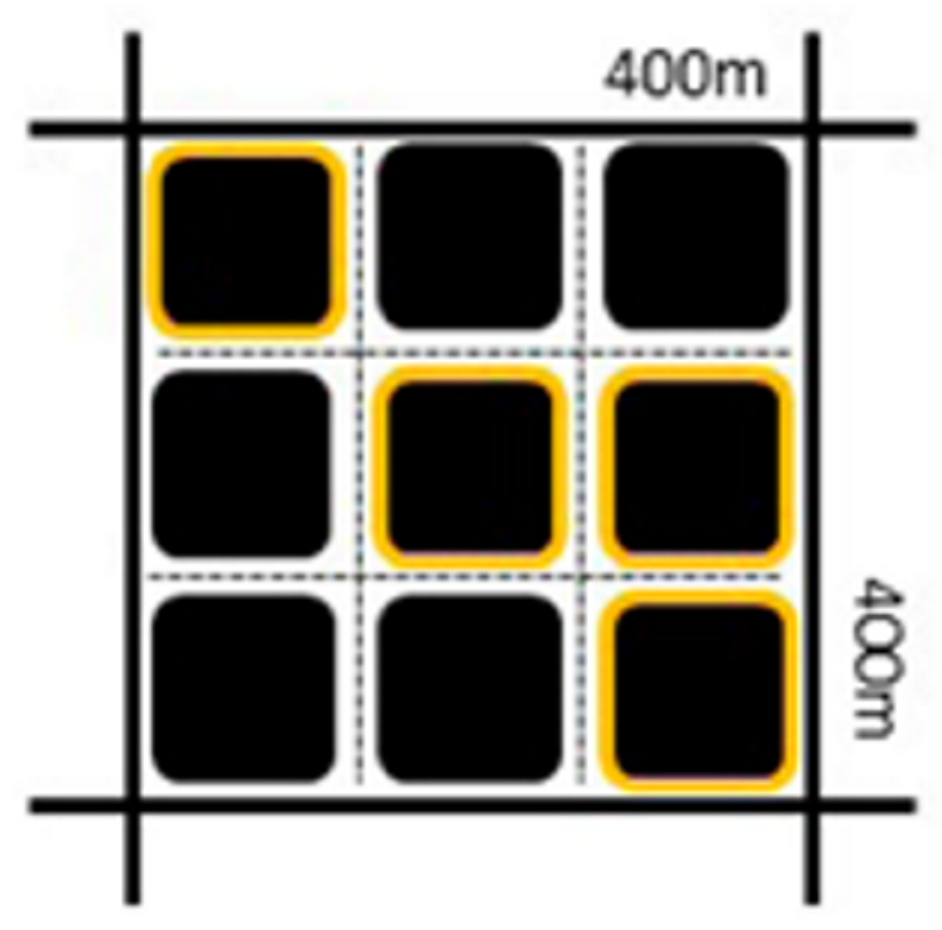

| Learning from the Barcelona City superblocks, 400 m × 400 m modules are created with inner-minor streets within the clusters bounded by arterial roads at the perimeter. The superblock scale is bigger than a regular city block (usually 100 m × 200 m) but smaller than a neighborhood (over 800 m). All essential amenities and community services are planned within the superblock and a 5 min walking distance (400 m). The safe “green” streets within the superblock help to improve walkability to access community facilities. The proximity of services and social infrastructure also improves community engagement. | All essential amenities and community services are planned within the superblock within a 5-min walking distance (400 m); risk of oversupply of amenities if the right densities are not met within the superblock. |

| The Neighborhood Scale | ||

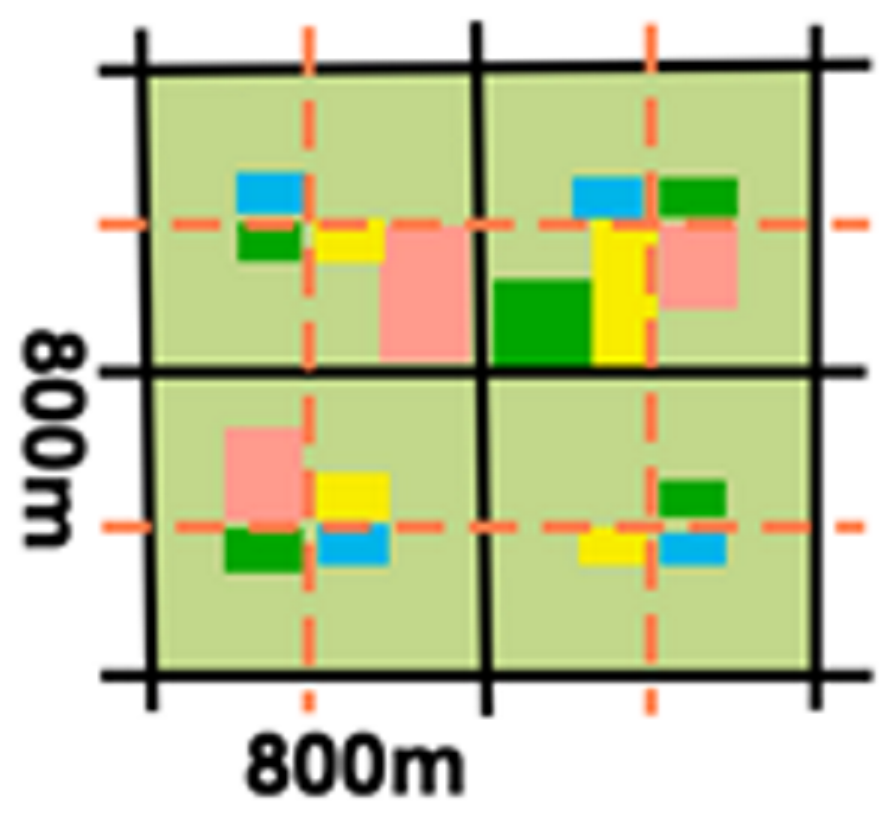

| Neighborhood scale was first defined in 1929 by Clarence Perry as a quarter-mile pedestrian shed [26]. Within the Singapore Planning context, a neighborhood unit (800 m × 800 m, 10 min walking distance) has around 4000 to 6000 dwelling units with their own neighborhood centers (NC) with shops, primary and secondary schools, and parks. | Limited consideration for elderly and people with reduced mobility |

| Form | Distance | Services |

|---|---|---|

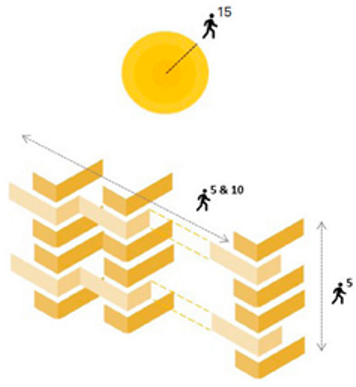

| Five-min walk (250 m–400 m) from center to the edge—daily needs, a range of housing types, and some scale amenities are planned. Five-min walking vertical neighborhood using vertical transport; mixed use building to plan amenities for daily need. | Daily needs, a range of housing types, and a center (generally a public square or main street with minimal mixed use), small businesses. |

| A 600–800 m walk from the center to the edge—housing types, daily amenities/essential services, and some neighborhood-level facilities. Utilizes vertical transport with 5 min walks to access connected buildings; mixed-use buildings are designed to include amenities for daily needs. | Range of housing type, daily amenities and essential services to cater to different demands, including some neighborhood-level facilities. |

| A 15-minute walk should cover a distance of approximately 1000–1200 m. People can reach neighborhood amenities using vertical transport and then walk for 10 min to access connected buildings. Mixed-use buildings include amenities for daily needs-public and community centers, supermarkets, and local working opportunities, serving multiple neighborhoods. | General merchandise, public (primary) schools and community clubs, sports centers, small playgrounds to larger parks that serve multiple neighborhoods and local working opportunities. |

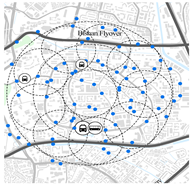

| The 15-minute Spatial Model with overlapping zones for sharing amenities between different neighborhoods | Higher order amenities such as library, botanic garden, hospitals, universities, etc. |

| 15 min cycling shed with 15 min walk sheds within; 4800 m from center to edge | Major cultural, medical, and higher-education facilities, regional parks, major employers, access to intercity transit. |

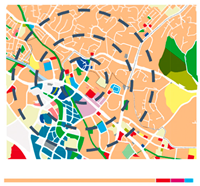

| Descriptions | Part of Bouna Vista HDB and Holland Village | Clementi North and Central | Toa Payoh Central |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Holland Village offers diverse amenities and a low-density environment with private landed houses. The business parks in the area provide numerous job opportunities. | A high-density mature HDB town with easily accessible amenities, mixed-use buildings, combining commercial, residential, and public transit facilities. Amenities within the 15-minute neighborhood are easily accessible by walking or cycling. | A high-density, mature, inclusive and livable environment with barrier-free amenities, recreational facilities, and plenty of activities are held regularly. |

| Density (2020)/km2 | 10,906 | 18,000–23,878 | 25,305–28,000 |

| Land use | Land use in Holland Village is predominantly residential, with some business areas. | Land use in Clementi is predominantly residential, with amenities comprehensively distributed within a 15 min walking radius. | Land use is mainly residential, with well-distributed amenities, including multiple children’s parks and retail shops for every need. |

|  |  | |

| Distribution of Amenities | Most amenities are within a 15 min walk. Although essential services like food courts and markets are centrally located, due to the unequal distribution of amenities, it takes longer to reach them from some peripheral areas. | Most amenities and essential services are within a 15 min walk. | Good distribution of amenities, improved walkability |

|  |  | |

| Mobility | The business park is separated from the residential areas by Commonwealth Avenue, making commuting less convenient by walking or cycling. Monofunctional districts with limited walkability. | Limited pedestrian and cycling paths, especially across the AYE and West Coast Highway, make it inconvenient for people to access their daily needs. | Traffic-free pedestrian areas with universal access within the residential zones create a more encouraging walking environment. The 5, 10, and part of the 15 min walking areas are well protected from vehicular traffic along the arterial roads surrounding the neighborhood. |

|  |  |

| Analysis | Challenges | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| Part of Bouna Vista HDB and Holland Village |

|

|

| Clementi North and Central |

|

|

| Toa Payoh Central |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zan, C.; Bhatia, R.; Samant, S. Reimagining the High-Density, Vertical 15-Minute City. Buildings 2025, 15, 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101629

Zan C, Bhatia R, Samant S. Reimagining the High-Density, Vertical 15-Minute City. Buildings. 2025; 15(10):1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101629

Chicago/Turabian StyleZan, Chenyu, Ruchi Bhatia, and Swinal Samant. 2025. "Reimagining the High-Density, Vertical 15-Minute City" Buildings 15, no. 10: 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101629

APA StyleZan, C., Bhatia, R., & Samant, S. (2025). Reimagining the High-Density, Vertical 15-Minute City. Buildings, 15(10), 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101629