1. Introduction

With the change in disease spectrum and population structure brought about by China’s economic and social development, people’s healthcare needs have undergone a major adjustment, and the healthcare model is changing from the traditional therapeutic medical treatment to life support healthcare. Compared to large hospitals, med–small-sized hospitals (with 20–299 beds) will play a major role in this transformation, but hospitals often take 3–5 years or more from design to construction. In order to guide architects to make hospital planning and design that meets future needs, this study aims to explore the perceived value of patients to med–small-sized hospitals and identifies the key points of planning and design that can enhance the value of med–small-sized hospitals in terms of functional configuration, spatial environment, etc.

First of all, lifestyle diseases caused by bad lifestyle habits, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, are gradually becoming major challenges to global health [

1], and China is no exception. Lifestyle diseases can be fundamentally cured mainly by improving living habits [

2], so the importance of life support healthcare based on chronic disease treatment, rehabilitation and health guidance will gradually become prominent in the future [

3]. Med–small-sized hospitals are the main undertakers of life support healthcare system [

4]. Secondly, in China’s healthcare system, large hospitals are generally responsible for the treatment of acute and difficult diseases, while med–small-sized hospitals participate in the treatment of common and frequently occurring diseases, home care, and community healthcare, which main users include the elderly and children. In 2021, the population aged 65 and above in China reached 14.2% and entered the aging society [

5]. The increase in the proportion of elderly people has led to a decrease in the demand for acute medical treatment and an increase in the demand for rehabilitation, chronic care, and home care and nursing [

6]. With the implementation of the two-child and three-child policies, the proportion of newborns and teenagers has increased, leading to a higher demand for maternal and child healthcare and services [

7]. To sum up, med–small-sized hospitals close to residents’ lives and with high accessibility will play an increasingly important role [

8]. However, the actual situation in China is that large hospitals are overcrowded and the utilization rate of med–small-sized hospitals is low, and the perceived value is an important indicator of patients’ recognition of policies or environments. Therefore, the author believes that the low perceived value of patients toward med–small-sized hospitals is the main reason why Chinese patients are reluctant to seek treatment in med–small-sized hospitals.

Disease spectrum transformation and demographic aging are common problems faced globally, so there are many experiences in the construction of med–small-sized hospitals that China should learn from. Taking Japan [

9], which is similar to China and has entered the super-aged society in advance [

10], as an example, after conducting a large number of surveys on patients’ healthcare needs, satisfaction [

11], and hospital function evaluation [

12], Japanese scholars proposed the slogan “high-quality chronic care makes Japan strong”, expanding the role of chronic hospitals, which should be closely integrated with the local communities [

13] and be responsible for all healthcare treatment, except for the highly acute phase, and the important pillar supporting the chronic care system is med–small-sized hospitals [

14]. Through the case study of Japanese hospitals, it can be seen that there are many types of med–small-sized hospitals in Japan, with a large outpatient volume, including specialized hospitals that participate in the healthcare division and cooperation system in urban areas with high population density and comprehensive hospitals that provide services from the acute stage and rehabilitation stage to hospice care in areas with low population density. On the other hand, many design studies addressing the diversity of wards were also found [

15], such as studies on design strategies for rehabilitation wards, dementia care wards, hospice wards, etc. There is also some research on the impact of technological developments such as telemedicine and patient portals [

16] on hospital design. Given that patients around the world perceive different values for med–small-sized hospitals, this affects their visiting behavior and, in turn, their architectural design. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct research on the perceived value among Chinese patients.

The original concept of perceived value is based on consumers’ perception of “what they have received” and “what they have given” from products and services [

17,

18,

19] and was later extended to tourism and geographical studies [

20], psychological research [

21], transportation policy studies [

22], and environmental impact and urban studies [

23]. With the introduction of perceived value theory into the field of healthcare research, it provides a broad perspective on patient needs and has even influenced the philosophy of hospital management to a certain extent, meaning that patients, together with all their emotional and social needs, became the focus of hospital management strategy and the basic starting point of architectural design [

24].

A space environment is the carrier for healthcare professionals to carry out medical behavior [

25], and it is also the main carrier for patients’ perceived value of a hospital. The perceptual experience of patients in the hospital environment is a comprehensive feedback on the spatial function, atmosphere, and overall environmental quality [

26]. This perception is comprehensive and multidimensional, involving the layout of the hospital functional space, color, light, sound, smell, and other aspects [

27]. These perceptual experiences help us to understand more deeply the interaction between patient and healthcare spatial environment.

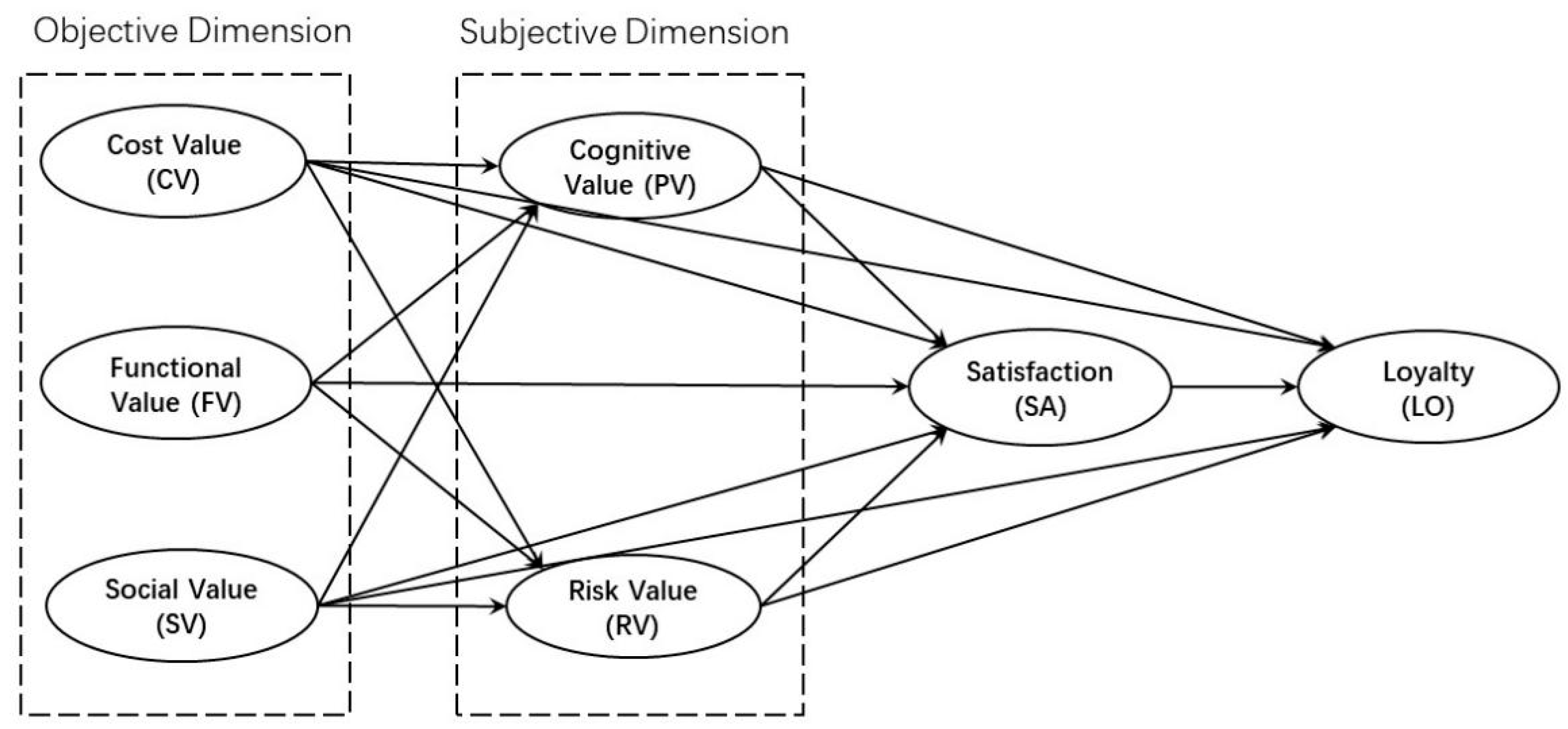

Despite the large number of med–small-sized hospitals in China, most of the related studies have been conducted from the perspective of architectural design [

28,

29], and less studies have been focused on patients’ perceptions. Therefore, based on the theory of perceived value, this study constructs a structural equation model of patients’ perceived value of med–small-sized hospitals, reveals their internal network relationships, and explores the correlation between various types of perceived value dimensions in med–small-sized hospitals and patients’ satisfaction and behavior intention based on loyalty. This paper identifies Chinese patients’ demands for the functional configuration and environmental design of med–small-sized hospitals and focuses on the perceived value elements of life support healthcare facilities. After that, we propose sustainable planning and design strategies for med–small-sized hospitals based on the actual research situation in Nanjing, which will serve as a reference for architects.

4. Results

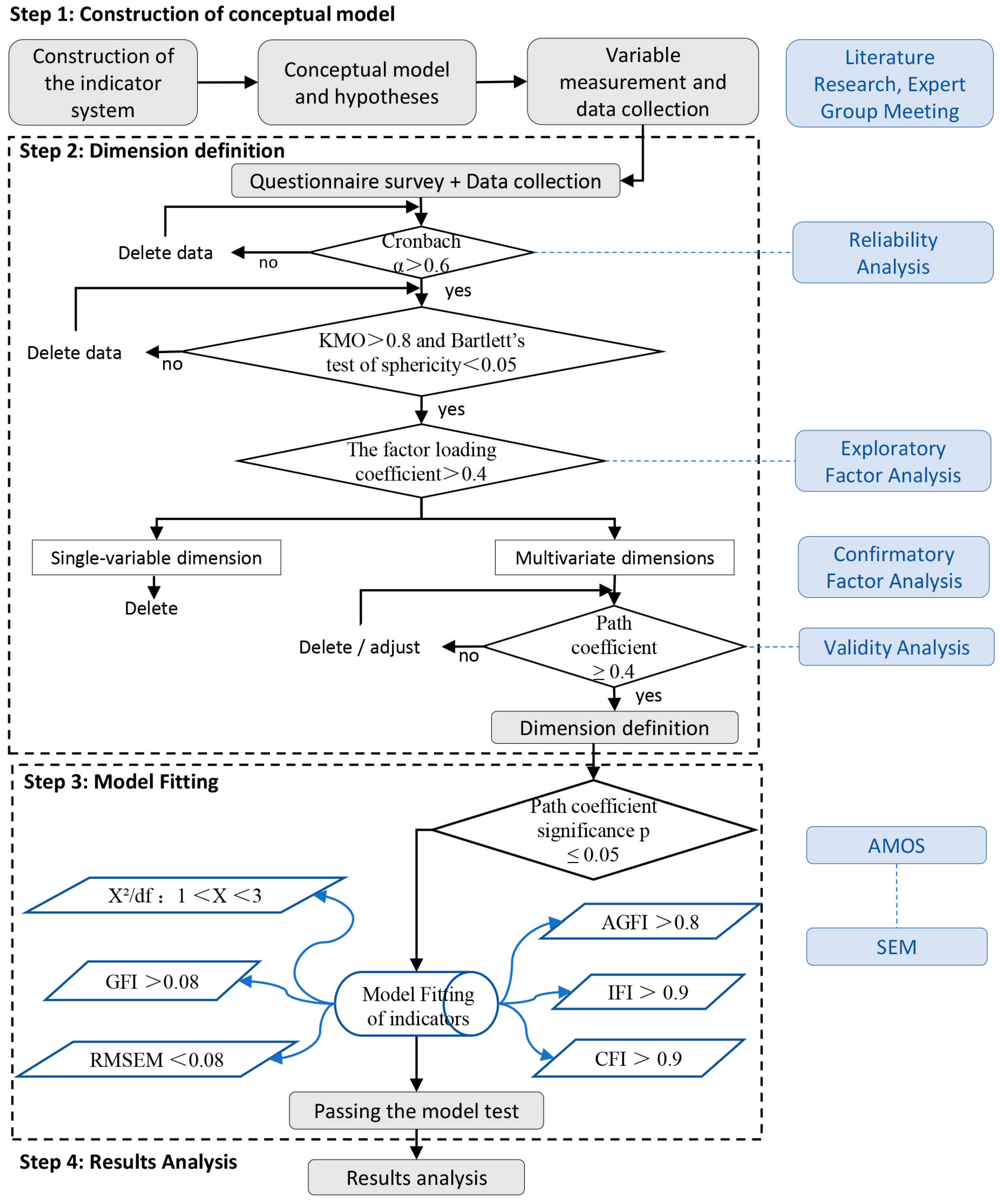

4.1. SEM Validation

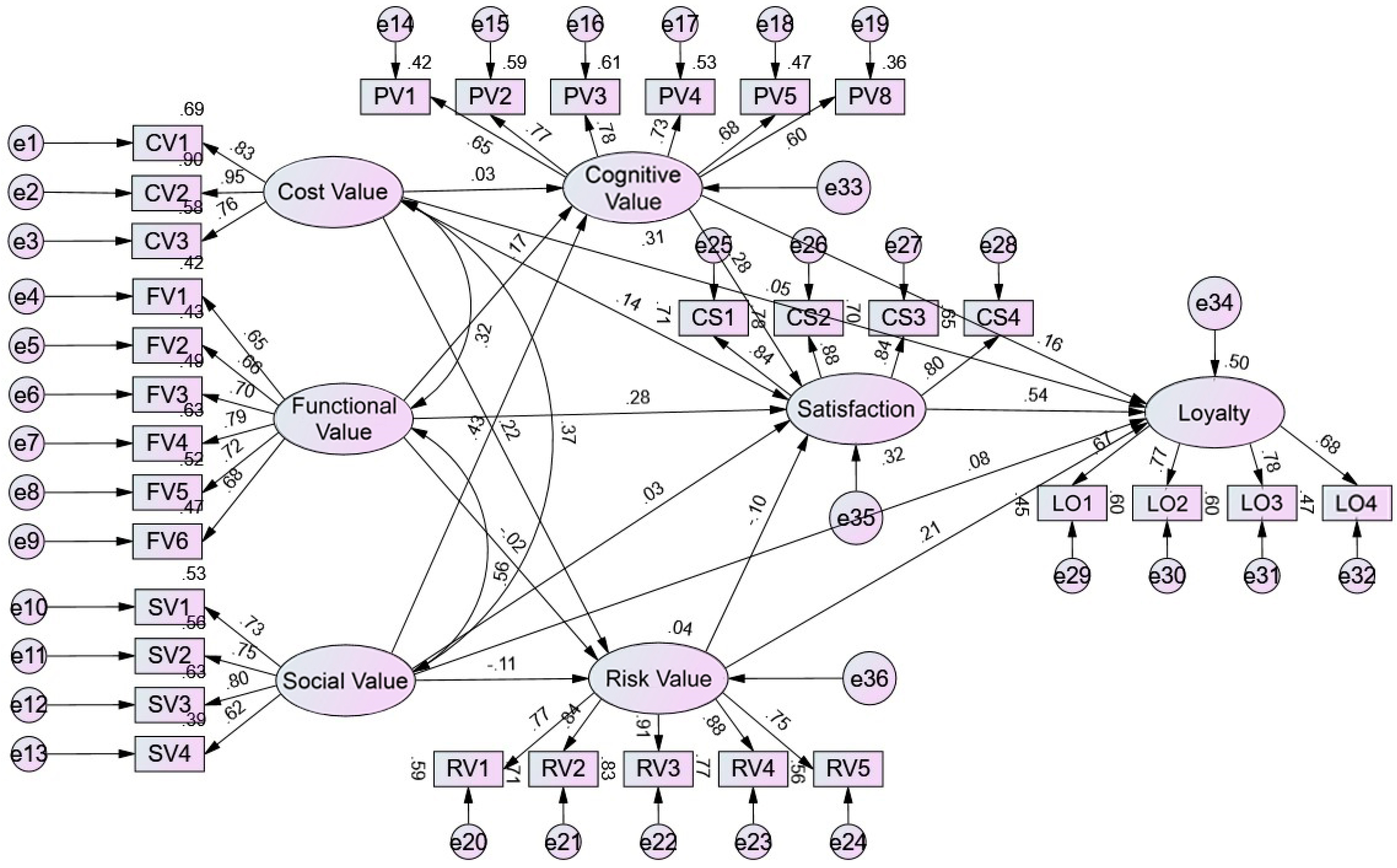

Based on the data processing results mentioned above, AMOS 26.0 software was used to build a structural equation model of patient perceived value of med–small-sized hospitals, and the significance and importance of the model variables and the collinearity of the three exogenous variables were tested by non-standardized calculation and standardized calculation [

43,

44]. The running results of the model are shown in the

Figure 3.

The next step is to perform a goodness-of-fit test, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the SEM. The initial model (

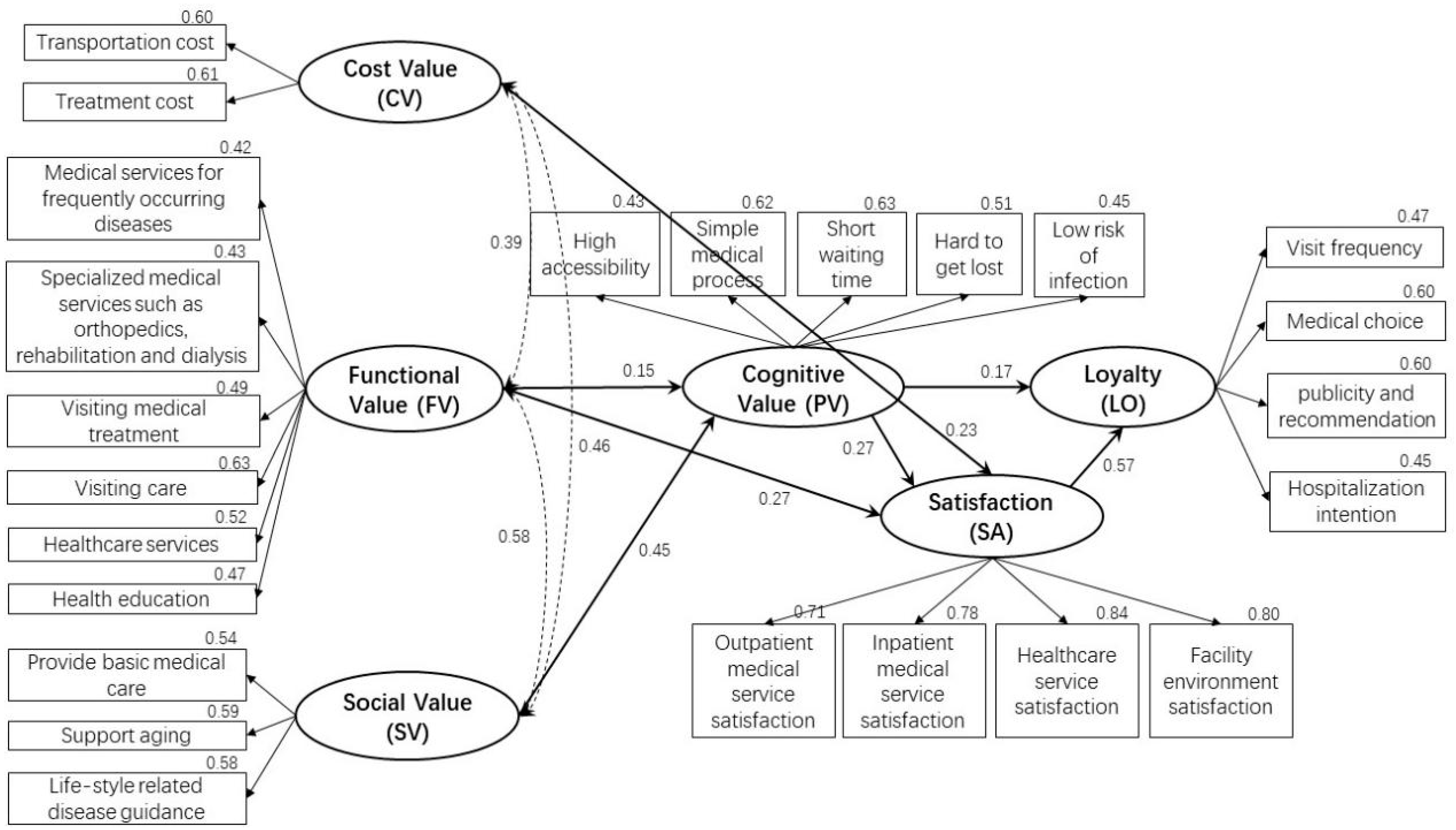

Figure 3) failed to pass the goodness-of-fit test, so the model was modified until the final model (

Figure 4) met the verification requirements in the fit degree test (

Table 7), and the AVE values among the measured variables in the convergent validity were all >0.5 and the CR values were greater than 0.8. The correlation coefficients among the measured variables in the discriminant validity test were smaller than the square root of the AVE values (

Table 8). The final model (

Figure 4) displayed the observed variables with large explanatory coefficients corresponding to each measurement variable and retained seven paths and correlation coefficients with high significance among the measurement variables.

4.2. Results of SEM

The final SEM revealed that among cost value, functional value, social value, and cognitive value, functional and cognitive values, have the greatest impact on patient satisfaction and loyalty. This indicated that, for med–small-sized hospitals, functional configuration and environmental design can significantly enhance the hospital’s value. Additionally, in the behavioral statistics based on patient loyalty, it was found that patients’ willingness to go to the inpatient department is the lowest.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of the Final Model and Hypothetical Model

Comparing the final model with the initial hypothetical mode, the results showed that (1) the risk value was removed due to low correlation with the overall structural model, indicating low sensitivity in patients’ subjective perception of the potential negative impact on med–small-sized hospitals, and (2) the hypothetical model sets a total of 16 correlation paths among the variables, while the final model retained a total of 7 correlation paths among the 6 potential variables, reflecting the real path relationships between patient perceived value variables, satisfaction variables, and loyalty variables. In addition, the final model relationship path diagram in

Figure 3 shows that there may be a mediating effect between patient perceived value and loyalty; that is, patient loyalty may be driven by the direct and indirect dual paths of intermediary variables such as cognitive value and satisfaction.

4.4. Important Relationship Path Interpretation

In the pathway of the “objective dimension—cognitive value”, only functional value and social value will have a positive impact on cognitive value, while cost value does not. Social value has a greater impact, with a path coefficient of 0.45. The provision of basic medical care, support for aging, and guidance on lifestyle-related disease are the three most important aspects constituting the social value of med–small-sized hospitals. Among the six observed variables of functional value, visiting care (0.63) had the largest explanatory coefficient, followed by health services (0.52), while medical services for common diseases and frequently occurring diseases (0.42) had the smallest explanatory coefficient.

In the paths of “patient perceived value—satisfaction”, cost value, functional value, and cognitive value all have a direct positive impact on satisfaction, with path coefficients of 0.23, 0.27, and 0.27, respectively. In the observed variables of cost value, because med–small-sized hospitals are close to the residents’ life circle, the time cost for patients can be ignored.

Analyzing the paths between “cognitive value—satisfaction—loyalty”, cognitive value, as the subjective perception of patients, has a direct positive influence on satisfaction and loyalty, with path coefficients of 0.27 and 0.17, respectively. Among the five observed variables of cognitive value, short waiting time (0.63), short medical process (0.62), and easy navigation due to smaller size (0.51) are the three variables with the most significant impact, and they represent important directions in architectural environmental design to enhance patient experience. Additionally, satisfaction also positively influences loyalty, with a path coefficient of 0.57, which is greater than the impact of cognitive value on loyalty. Among the observed variables of satisfaction, outpatient medical services, inpatient medical services, healthcare, and facility environment have high explanatory coefficients. Notably, among the four behavioral intentions of loyalty, the coefficient for the hospitalization intention is the lowest, suggesting that the inpatient department of med–small-sized hospitals has the lowest attractiveness to patients.

4.5. Mediation Effects Tests and Path Analysis

There are both direct and indirect influence relationships between variables. In the final SEM, six paths with mediating effects are shown. Firstly, AMOS 26.0 software was used to test the significance of indirect effects among the model variables [

45,

46] (

Table 9). The results indicated that the indirect effects in the path of “functional value—cognitive value—satisfaction” did not pass the significance test. This suggested that, compared to the direct impact of functional value on satisfaction, the indirect impact of cognitive value can be ignored. The mediation effect of the remaining five paths all passed the significance test.

Then, the specific effect values of the full effect, direct effect, and indirect effects among the variables were calculated, and the results are shown in

Table 10 below.

According to the data in the table above, it can be explained as follows: (1) Cognitive value has both direct and indirect effects on loyalty, while satisfaction has only direct effects on loyalty, and other variables have only indirect effects on loyalty. (2) The direct impact of cognitive value on loyalty is equivalent to its indirect impact on loyalty through satisfaction. (3) Social value, functional value, and cost value indirectly influence loyalty through cognitive value or satisfaction. Changes in cost value have a weak impact on loyalty, followed by social value, while functional value has the most significant impact on loyalty.

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences from Previous Research Results

In previous research mainly focused on patient perceived value indicators in large hospitals [

35] such as public hospitals [

24], private hospitals, university hospitals, or military medical academy [

36], patients and their families placed the highest emphasis on the treatment effectiveness for acute medical conditions and complex diseases, as well as medical costs [

47] and the efficiency of communication with healthcare providers [

48]. Their perception of value regarding the medical environment and spatial design was quite low [

41]. However, the results of this work indicated that, for med–small-sized hospitals, functional configuration and patient experience are the two primary perceived value factors for patients. This suggested that the importance of functionality and environmental design is greater for med–small-sized hospitals than for large hospitals.

The reason for this can be attributed to the fact that med–small-sized hospitals often handle the treatment of mild cases and chronic illnesses, which are significantly less complex than those treated in large hospitals. Additionally, most med–small-sized hospitals in China are non-profit institutions established by the government, resulting in lower treatment costs. The community hospital network, which closely aligns with the living circles of residents, enhances accessibility for the public. This greatly reduces both the financial and transportation costs for citizens, making these two value factors, which are relatively important for large hospitals, of lower priority for med–small-sized hospitals.

Furthermore, in terms of spatial environment design, large hospitals have a substantial size and complex functions, making it easy for patients to get lost. Additionally, with the current overcrowding in large hospitals, the waiting times and processes for receiving care can become lengthy, diminishing the patient experience. In contrast, med–small-sized hospitals, due to their smaller size and relatively simple functions, are less likely to cause patients to lose their way, and the care processes are shorter. This gives them a natural advantage in patient experience. Moreover, with the pandemic of COVID-19 in recent years [

49], patients’ cognitive sensitivity to hospital infections has increased. Med–small-sized hospitals, characterized by their smaller volume and flexible space, can easily distinguish between healthy people and unhealthy people in a streamline design. This reduces the possibility of hospital infection and thus improves the patient safety.

In summary, due to the different functional positioning in the medical system, large hospitals and med–small-sized hospitals also have great differences in the medical experience brought to patients by scale, spatial layout, and environmental design. Therefore, many general hospitals and specialty hospitals should also classify and separately discuss their functional configurations, planning layouts, and spatial environments based on bed counts of 300 or more and 20 to 299.

5.2. Optimization Strategies for the Planning and Design of Med–Small-Sized Hospitals

The results presented by the final model in conjunction with the past literature and the research findings from Nanjing are further analyzed and discussed. Optimization strategies for the planning and design of med–small-sized hospitals are proposed.

- (1)

Promote diversified development and collaboration based on regional characteristics

In the analysis of the final model, this work can still identify the shortcomings of med–small-sized hospitals. Although the number of med–small-sized hospitals in China is large, with dense and average distribution, they all provide the same basic medical services for frequently occurring diseases, which reduces the functional value of hospitals for patients and residents. Therefore, it is necessary to take a diversified development path based on the characteristics of the location. For example, if land in the city center is lacking, specialized hospitals with less bed demands such as dialysis hospitals, orthopedic hospitals, and dental hospitals can be built. On the contrary, in suburban areas where medical resources are scarce, the scale of community hospitals can be appropriately increased to undertake comprehensive medical services from acute to chronic stages within the service scope. In addition, functional planning can be carried out for various small and medium-sized hospitals within a certain area, and a collaborative network can be established [

50]. For instance, to support and enhance the community’s elderly care medical system, nursing hospitals, geriatric day hospitals [

51], rehabilitation hospitals for maintenance care, and hospice care hospitals [

52] can be integrated into a planning and construction framework around high-age communities or in conjunction with elderly care institutions.

- (2)

Optimize functional configuration

Functional value is a key aspect that patients prioritize. According to this survey, with the development of the home-based care for the aged concept, there is an increase in the proportion of women and children seeking medical treatment, as well as a rise in the number of sub-healthy individuals. Med–small-sized hospitals need to enhance or expand their medical service functions and departmental areas related to elderly chronic diseases, home care, maternal and child health, and adult diseases. Furthermore, research on several hospitals in Nanjing indicates that departments such as gynecology, pediatrics, dialysis, nursing, and rehabilitation are currently in high demand among patients. Additionally, following the pandemic, many studies have highlighted the need for hospitals to reserve space that can respond to sudden public health emergencies or allow for flexible adjustments in functionality.

- (3)

Maintain the advantage of an efficient and streamlined medical process

Med–small-sized hospitals are less likely to cause patients to get lost, as their medical processes are shorter, which enhances patients’ experience and their awareness of the importance of the facility’s environment. Therefore, in terms of spatial layout and environmental design, it is essential to maintain these advantages. This includes designing the flow in outpatient departments with high crowd density; creating waiting spaces for popular departments such as traditional Chinese medicine, pediatrics [

53], and maternal and child health; implementing noise reduction design in public areas of the hospital; and optimizing the lighting environment in treatment areas.

- (4)

Optimize the inpatient department

In addition, compared to the situation that it is difficult to obtain a bed in the inpatient department of a large hospital, the willingness of patients to go to med–small-sized hospitals for inpatient treatment is not high. For example, the average hospital bed utilization rate in this survey was only 60%. It can be attributed to two main factors. One the one hand, the quality of treatment and nursing in med–small-sized hospitals is not high. On the other hand, there are no relevant guidelines for the functional classification of beds in med–small-sized hospitals, which cannot meet the inpatient needs of medical treatment, rehabilitation, nursing, etc.

Therefore, it is recommended to appropriately reduce the number of beds during planning. At the same time, due to the increase in the number of elderly and pediatric patients, the proportion of rehabilitation beds for the elderly and children, as well as beds that combine medical care and nursing, can be appropriately increased. Distinct design should be applied to inpatient units for rehabilitation and nursing [

54]. Regarding room types, many research findings indicate that single rooms can significantly enhance patient satisfaction. Thus, the number of single rooms can be increased as appropriate based on the situation. Finally, in designing the ward environment, since the length of stay for chronic disease and nursing beds tends to be longer, the design approach can reference residential design [

55]. In the design of wards for patients who are bedridden for extended periods, efforts should be made to help patients perceive the changes in the external natural environment as much as possible [

56].

6. Conclusions

As China enters an aging society, changes in population structure and shifts in disease patterns have led to a major transformation of the healthcare needs of people from traditional therapeutic medical care to the life support healthcare model. Med–small-sized hospitals are expected to play a major role in this transition compared to large hospitals. However, hospitals often take 3–5 years or more from design to construction. In order to guide architects in planning and designing for future needs, this study based on the patient’s perspective utilizes perceived value research results to create a structural equation model of patient perceived value in Chinese med–small-sized hospitals. The model includes six dimensions: cost value, functional value, social value, cognitive value, satisfaction, and loyalty, comprising a total of 24 observation variables. The final model demonstrated good reliability, validity, and fit during testing. The model results intuitively indicate that optimizing a functional and spatial environmental design can significantly increase the value of hospitals and that there is a need to enhance the attractiveness of inpatient departments to patients. Based on these results, combined with the past literature and research findings from Nanjing, four optimization strategies were proposed for the planning and design of med–small-sized hospitals: promote diversified development and collaboration based on regional characteristics, optimize functional configuration, maintain the advantages of efficient and streamlined medical processes, and optimize the inpatient department.

This study investigates hospital design from the perspective of perception; uses the results of patient perceived value research to build a structural equation model; quantifies the degree of influence of the functional configuration, spatial environment, and other elements of perceived value of med–small-sized hospitals on patient satisfaction and loyalty-based behavior; and fills the gaps in the research of med–small-sized hospital design. It also combines the questionnaire data and field research to propose planning and design strategies for the sustainable development of med–small-sized hospitals in Nanjing, as well as providing important design references for architects.

However, there are still some limitations in this work: (1) The research location is in Nanjing, China, so the results of the study will be affected by the geographical limitations, and (2) the number of hospitals and respondents is limited, so the generalizability of the patient perceived value model in this study remains to be further empirically tested and verified.

In addition, different characteristics of the population, such as age, education, family structure, income, etc., will also affect the configuration of function planning. Therefore, in future research, the authors will conduct statistical analysis on the demographic differences within the surveyed population, particularly focusing on the varying needs of elderly and non-elderly people.