Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Evaluating Historic Sites in Huai’an Ancient Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historic Sites

2.2. Research on Historic Sites

- A.

- Theory of preservation and restoration of historic sites

- B.

- Practice of preservation and restoration of historic sites

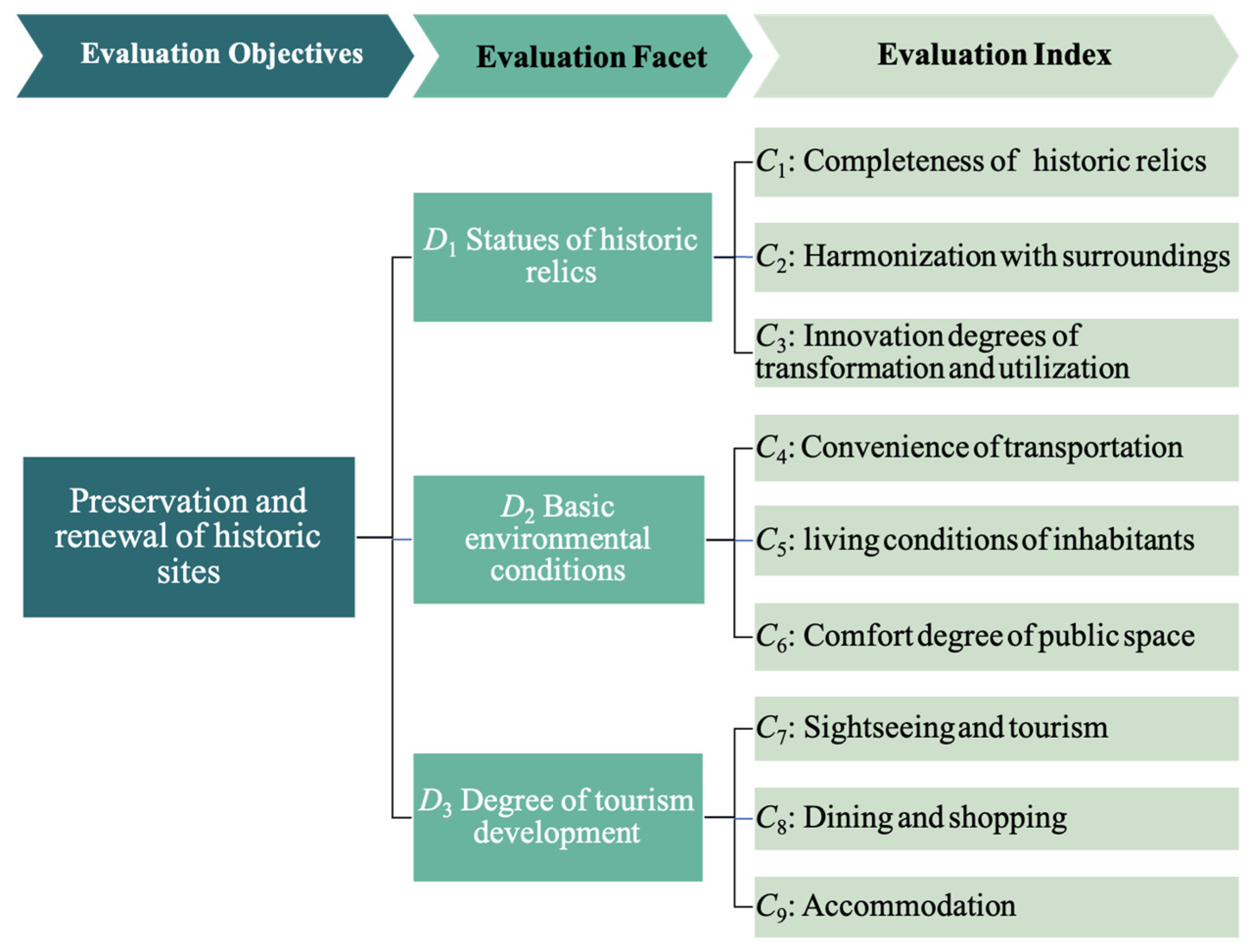

2.3. Determination of Evaluation Indexes

3. Research Objects and Methods

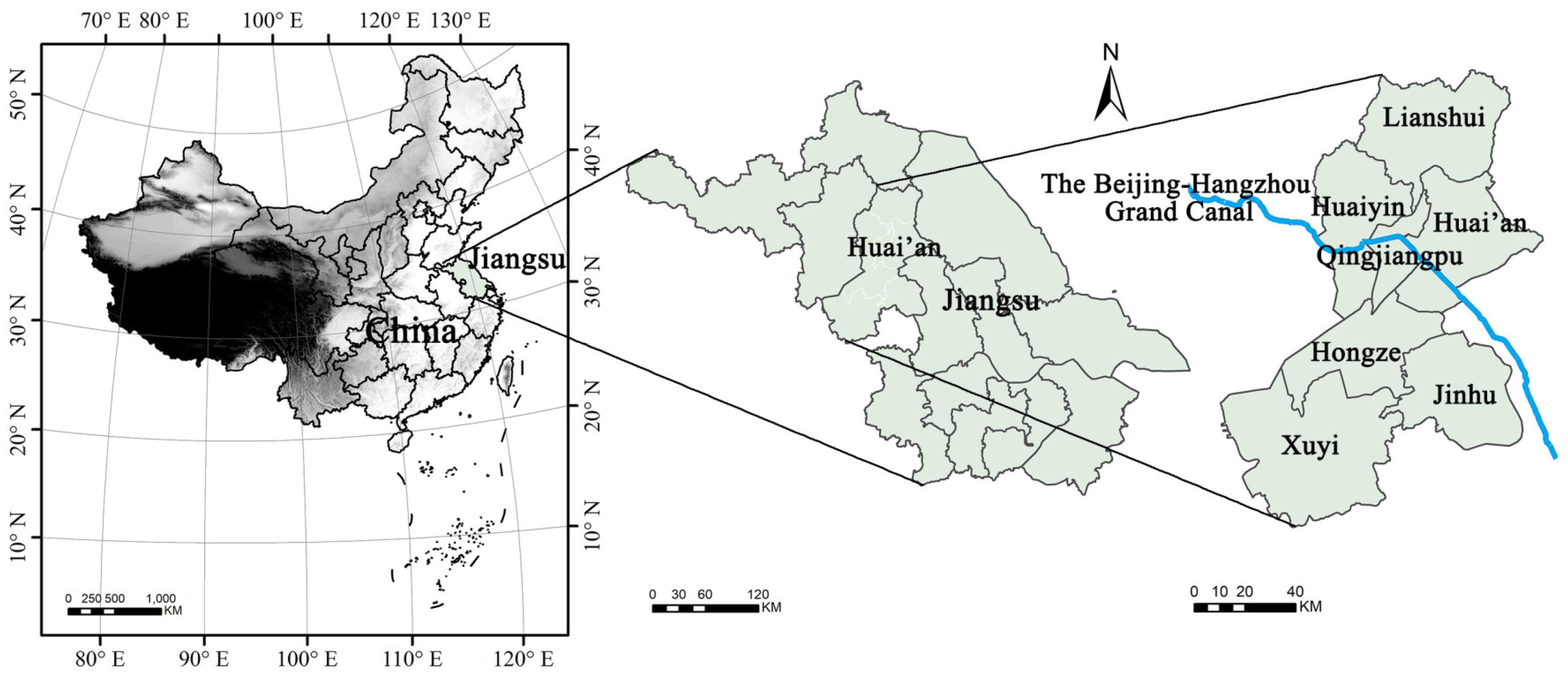

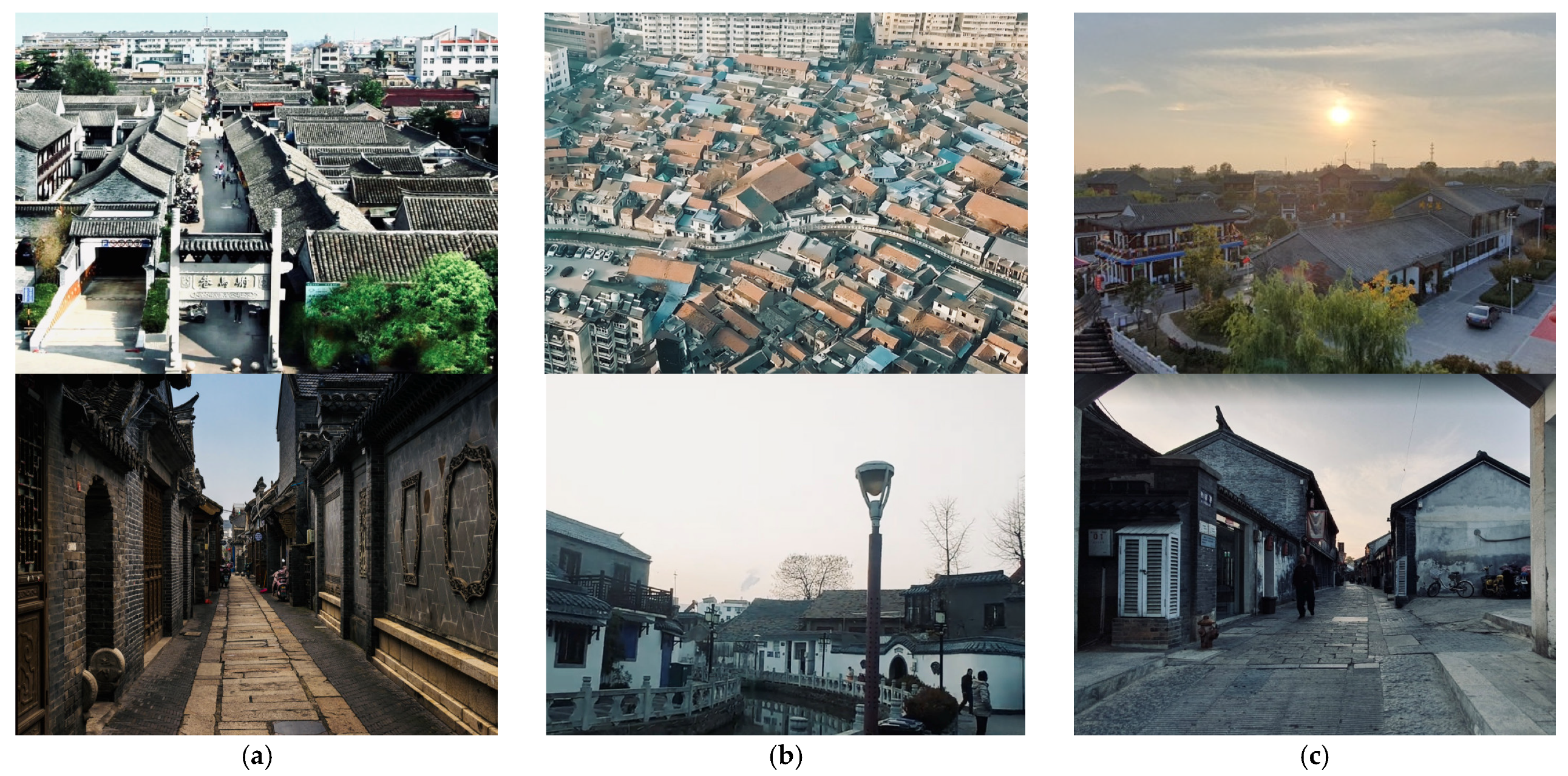

3.1. Study Area: Historic Sites in Huai’an

3.2. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM)

3.2.1. Concept and Application of Analytic Hierarchy Process

3.2.2. Calculation Steps

- (1)

- Construction of a judgment matrix

- (2)

- Calculations of eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- (3)

- Consistency check

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Weight Analysis of Evaluation Indexes

4.2. Empirical Study

4.3. Suggestion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andra-Topârceanu, A.; Verga, M.; Mafteiu, M.E.; Andra, M.-D.; Marin, M.; Pintilii, R.-D.; Mazza, G.; Carboni, D. Vulnerability Analysis of the Cultural Heritage Sites—The Roman Edifice with Mosaic, Constanța, Romania. Land 2023, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, J. Architecture in Conservation: Managing Development at Historic Sites; Routledge: Oxfordshire, England, 1994; Available online: https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=eholJejLxEMC&lpg=PP2&ots=y2wG9a9BXf&lr&hl=zh-CN&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Shirvani Dastgerdi, A.; De Luca, G. Specifying the Significance of Historic Sites in Heritage Planning. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2018, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Ma, Y. Network Construction for Overall Protection and Utilization of Cultural Heritage Space in Dunhuang City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, S. Cultural Selection and National Identity: Establishing Historic Sites in a National Framework, 1920-1939. Public. Hist. 1996, 18, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łakomy, K. Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Sun, Y. Power relationships and coalitions in urban renewal and heritage conservation: The Nga Tsin Wai Village in Hong Kong. Land. Use Policy 2020, 99, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, L.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B.; Karač, Z.; Kraus, I. Disappearance and Sustainability of Historical Industrial Areas in Osijek (Croatia): Three Case Studies. Buildings 2022, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B.J. Urban heritage: Putting the past into the future. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2013, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosagrahar, J.; Soule, J.; Girard, L.F.; Potts, A. Cultural heritage, the UN sustainable development goals, and the new urban agenda. BDC. Boll. Del. Cent. Calza Bini 2016, 16, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K. Urban conservation and spatial transformation: Preserving the fragments or maintaining the ‘spatial spirit’. Urban. Des. Int. 2000, 5, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z. Legal protection of cultural heritage in China: A challenge to keep history alive. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2016, 22, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. The context of the Venice Charter (1964). Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 1998, 2, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y. The scope and definitions of heritage: From tangible to intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, M.; Young, D. Revising the Burra Charter: Australia ICOMOS updates its guidelines for conservation practice. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2000, 4, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. International Trends in Historic Preservation: From Ancient Monuments to Living Cultures. APT Bull. J. Preserv. Technol. 1998, 29, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höpel, T.; Siegrist, H. (Eds.) Kunst, Politik und Gesellschaft in Europa seit dem 19. Jahrhundert; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; 270p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.R. Creating the Charter of Athens: CIAM and the Functional City, 1933-43. Town Plan. Rev. 1998, 69, 225–247. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40113797 (accessed on 17 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Łukaszewicz, A. A Reply to Fulvio Mazzocchi’s ‘Diving Deeper into the Concept of “Cultural Heritage” and Its Relationship with Epistemic Diversity’. Soc. Epistemol. Rev. Reply Collect. 2022, 11, 42–47. Available online: https://wp.me/p1Bfg0-6V7 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Pickard, R. Management of Historic Centres; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, England, 2001; Volume 2, Available online: https://xueshu.zidianzhan.net/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=GISRWIHVubAC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=Charter+for+the+Conservation+of+Historic+Towns+and+Urban+Areas&ots=PxNVWVdR2Y&sig=OzhNpE5Oid8i-V6oCV9cAjAYnF4 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Wai-Yin, C.; Shu-Yun, M. Heritage preservation and sustainability of China’s development. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J. The characteristics of formation, development and evolution of National Protected Areas in China. Int. J. Geoherit. Park. 2019, 7, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Gu, K.; Zhang, X. Urban conservation in China in an international context: Retrospect and prospects. Habitat. Int. 2020, 95, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Sykes, O.; Börstinghaus, W. Thirty years of urban regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The importance of context and path dependency. Prog. Plan. 2011, 75, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lah, L. From architectural conservation, renewal and rehabilitation to integral heritage protection (theoretical and conceptual starting points). Urbani Izziv 2001, 12, 129–137. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44180358 (accessed on 5 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Regenerative Design of Archaeological Sites: A Pedagogical Approach to Boost Environmental Sustainability and Social Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, J. Sustainable Renewal of Historical Urban Areas: A Demand–Potential–Constraint Model for Identifying the Renewal Type of Residential Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Ikebe, K. Urban heritage conservation and modern urban development from the perspective of the historic urban landscape approach: A case study of Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slave, A.R.; Iojă, I.-C.; Hossu, C.-A.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Petrișor, A.-I.; Hersperger, A.M. Assessing public opinion using self-organizing maps. Lessons from urban planning in Romania. Landsc. Urban. Plann. 2023, 231, 104641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, R. Europe’s Model and Exemplar Still? The French Approach to Urban Conservation, 1962-1981. Town Plan. Rev. 1982, 53, 403–422. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40111900 (accessed on 3 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Delafons, J.; Delafons, J. Politics and Preservation: A Policy History of the Built Heritage 1882–1996; Routledge: London UK, 2005; Available online: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=OmSQAgAAQBAJ&rdid=bookOmSQAgAAQBAJ&rdot=1&source=gbs_vpt_read&pcampaignid=books_booksearch_viewport (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Pickard, R. Area-Based Protection Mechanisms for Heritage Conservation: A European Comparison. J. Archit. Conserv. 2002, 8, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Timothy, D.J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: Cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Masciotta, M.-G.; García-Alvarez, J.; Ramos, L.F.; Oliveira, D.V.; Martín-Jiménez, J.A.; González-Aguilera, D.; Monteiro, P. Web-GIS approach to preventive conservation of heritage buildings. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T.; Guia, J.; Specht, J. Organic ‘folkloric’ community driven place-making and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M. Design Participation Theories. In Reviewing Design Process. Theories: Discourses in Architecture, Urban. Design and Planning Theories; Rezaei, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotterback, C.S.; Lauria, M. Building a Foundation for Public Engagement in Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Pereira Roders, A.; van Wesemael, P. Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities 2020, 96, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, R.; Hashempour, N.; Lotfi, M. Sustainable-resilient urban revitalization framework: Residential buildings renovation in a historic district. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletinckx, D. Virtual Archaeology as an Integrated Preservation Method. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2011, 2, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifko, S. Comprehensive Management of Industrial Heritage Sites as A Basis for Sustainable Regeneration. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, E. An Integrative Theory of Urban Design. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. Heritage protection for the 21st century. Cult. Trends 2008, 17, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Reyes, L.; Díaz-Lazcano, V.; Zumelzu, A.; Prieto, A.J. Resilience and sustainability assessment of cultural heritage and built environment: The Libertad pedestrian walkway in Valdivia, Chile. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 53, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, N.; Verpoest, L. Living with History, 1914–1964: Rebuilding Europe after the First and Second. World Wars. and the Role of Heritage Preservation/La. Reconstruction En Europe Après la Première et la Seconde Guerre Mondiale et le rôle de la Conservation des Monuments Historiques; Leuven University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, A.; Aly, R.; Ahmed, G. Toward sustainable urban development of historical cities: Case study of Fouh City, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban regeneration between cultural heritage preservation and revitalization: Experiences with a decision support tool in eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaa, D. The past as a catalyst for cultural sustainability in historic cities; the case of Doha, Qatar. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.P.; Seixas, J.; Palma, P.; Duarte, H.; Luz, H.; Cavadini, G.B. Positive Energy District: A Model for Historic Districts to Address Energy Poverty. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 648473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, A.B.; Ajekigbe, P.G. Poverty Alleviation in Nigeria: Need for the Development of Archaeo-Tourism. Anatolia 2007, 18, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Pajouhesh, P.; Miller, T.R. Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local. Environ. 2019, 24, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Contemporary Cultural Heritage and Tourism: Development Issues and Emerging Trends. Public. Archaeol. 2014, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, F.D. Cultural Tourism Potential, as Part of Rural Tourism Development in the North-East of Romania. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwajfah, M.M.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. Residents’ perceptions and satisfaction toward tourism development: A case study of Petra Region, Jordan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, D.T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Naismith, N.; Zhang, T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Tookey, J. A critical comparison of green building rating systems. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicioni, L.; Lupíšek, A.; Gaspari, J. Exploring the Common Ground of Sustainability and Resilience in the Building Sector: A Systematic Literature Review and Analysis of Building Rating Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, D. Designing a Smart, Livable, and Sustainable Historical City Center. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2022, 148, 05022023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirdar, G.; Cagdas, G. A decision support model to evaluate liveability in the context of urban vibrancy. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2022, 20, 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwajfah, M.M.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. The satisfaction of local communities in World Heritage Site destinations. The case of the Petra region, Jordan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, S.; Zhang, C. Authenticity, involvement, and nostalgia: Understanding visitor satisfaction with an adaptive reuse heritage site in urban China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ge, J.; Bai, M.; Yao, M.; He, L.; Chen, M. Toward classification-based sustainable revitalization: Assessing the vitality of traditional villages. Land. Use Policy 2022, 116, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Integrated Examination of Urban Form: Historicity and Socio-economic Vibrancy. In Conserving and Managing Historical Urban. Landscape: An Integrated Morphological Approach; Li, X., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 89–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Makore, B.N. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Targets: A Possible Harmonisation? Insights from the European Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.H.; Abdulla, Z.R.; Salih, N.M.M. Urban regeneration through post-war reconstruction: Reclaiming the urban identity of the old city of Mosul. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2019, 7, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A.; Jamaleddin, M. The authenticity of place-making. Archnet-IJAR: Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Truong, N.S.H.; Rockwood, D.; Tran Le, A.D. Studies on sustainable features of vernacular architecture in different regions across the world: A comprehensive synthesis and evaluation. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Zhang, L. Using multi-source big data to understand the factors affecting urban park use in Wuhan. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2019, 43, 126367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Ling, Y.; Lin, J.-C.; Liang, Z.-F. Research on the Development of Religious Tourism and the Sustainable Development of Rural Environment and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H. Does living in the vicinity of heritage tourism sites influence residents’ perceptions and attitudes? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1295–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeli, K. Public space and the challenge of urban transformation in cities of emerging economies: Jeddah case study. Cities 2019, 95, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Principles for public space design, planning to do better. Urban Design Int. 2019, 24, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnes, C.; Itoga, H.; Agrusa, J.; Lema, J. Sustainable Tourism Empowered by Social Network Analysis to Gain a Competitive Edge at a Historic Site. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.S.; Ritchie, B.W.; Papandrea, F.; Bennett, J. Economic valuation of cultural heritage sites: A choice modeling approach. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parga Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Sustainable tourism and social value at World Heritage Sites: Towards a conservation plan for Altamira, Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Pei, T.; Chan, C.-S.; Wang, M.; Meng, B. Tourism value assessment of linear cultural heritage: The case of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Peng, J. Introduction of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal and analysis of its heritage values. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2019, 26, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Rui, S. Research on the Historical Site Revival by the Perspective of Cultural Capital. Educ. Aware. Sustain. 2020, 3, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, R.; Shan, S.; Mori, S. Analyzing Spatial Structure of Traditional Houses in Old Towns with Tourism Development and Its Transformation toward Sustainable Development of Residential Environments in Hexia Old Town, in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of Jiangsu Provincial Government. Available online: http://zrzy.jiangsu.gov.cn/gtapp/nrglIndex.action?type=2&messageID=C710B244987BB66CE05010AC3302D99E (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Triantaphyllou, E. Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods. In Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods: A Comparative Study; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, H.; Baneshi, M.; Yaghoubi, M. Techno-economic and environmental design of hybrid energy systems using multi-objective optimization and multi-criteria decision making methods. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 282, 116873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FADLINA, F.; GINTING, G. Penerapan Aplikasi Travel Recommended Mencari Destinasi Wisata Di Sumatera Utara Menggunakan Metode Fuzzy Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) Berbasis WAP. Nuansa Inform. 2023, 17, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-b.; Klein, C.M. An efficient approach to solving fuzzy MADM problems. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1997, 88, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-J.; Liu, T.-Y.; Hwang, C.-L. Topsis for MODM. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1994, 76, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awodi, N.J.; Liu, Y.-k.; Ayo-Imoru, R.M.; Ayodeji, A. Fuzzy TOPSIS-based risk assessment model for effective nuclear decommissioning risk management. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 155, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yüksel, S.; Dinçer, H. An integrated decision-making approach with golden cut and bipolar q-ROFSs to renewable energy storage investments. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 25, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. What is the Analytic Hierarchy Process? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, H.B.; Yalpir, S.; Inam, S. Assessment of suitable shrimp farming site selection using geographical information system based Analytical Hierarchy Process in Turkey. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 235, 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, R.R.; Puthuvayi, B. A comprehensive literature review of Multi-Criteria Decision Making methods in heritage buildings. Procedia Eng. 2020, 32, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De FSM Russo, R.; Camanho, R. Criteria in AHP: A systematic review of literature. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 55, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Özdemir, M.S. How Many Judges Should There Be in a Group? Ann. Data Sci. 2014, 1, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list (accessed on 26 January 2023).

| Core Issues | Key Contents |

|---|---|

| Statuses of historic relics | Preservation: In the first half of the 20th century, theories about preservation and restoration, such as “organic restoration”, “preservation of integrity”, and “continuous renovation”, emerged [40,41,42]. |

| Renovation: France has taken a gradual approach through the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels to provide an operable basis for the style renovation of historic sites. The United States preserves the historical styles of cities through urban design. The UK has adopted “theme planning” and “action area planning” to improve the architecture, environments, transportation, and landscapes of historic sites [43,44,45]. | |

| Basic environmental conditions | Physical spaces: to improve the living conditions of inhabitants, as well as solve urban congestion and other problems. Residential orientation means that the material revival of a historical block prioritizes the residential functions, but also gives due consideration to other functions [46,47,48]. |

| Social problems, such as residential space differentiation and urban poverty, have been addressed through the active improvement of the living conditions of vulnerable groups around the world, such as the North Village (South Korea), Brindley of Birmingham (UK), and the Heiksch Community (Germany) [49,50,51]. | |

| Degree of tourism development | The preservation and maintenance of historic sites alone cannot give full play to their historical and cultural value. One effective way to bring their value into play is tourism development based on their heritage resources. The Castlefield Block of Manchester, England, has developed cultural and tourism industries based on local featured architecture and industrial landscapes, thus converting the historic site into a new highlight of the city [52,53,54]. |

| Evaluation Facet | Evaluation Index | Description |

|---|---|---|

| D1: Statuses of historic relics | C1: Completeness of historic relics | Integrity of architectural styles and the degree of retention of street spaces [40,41]. |

| C2: Harmonization with surroundings | Harmonization of architectural forms and the degree of integration with the new city [63,64]. | |

| C3: Innovation degrees of transformation and utilization | Use of modern techniques and languages for the upgrading and innovation of traditional architectural spaces, thereby meeting the needs of modern people [65,66]. | |

| D2: Basic environmental conditions | C4: Convenience of transportation | Organization, supporting services, accessibility, and continuity of transportation. The transportation supporting services include parking lots, safe passage, sidewalks, road greening, and so on [67,68]. |

| C5: Living conditions of inhabitants | Adherence to the people-oriented principle to safeguard the interests of the inhabitants and minimize adverse effects [48,69]. | |

| C6: Comfort degrees of public spaces | Landscape architecture, service facilities, ecological environments, etc. [70,71]. | |

| D3: Degree of tourismdevelopment | C7: Sightseeing and tourism | Experience of cultural landscapes, the cultural inheritance of historic sites, etc. [53,72]. |

| C8: Dining and shopping | Transformation of houses into commercial storefronts through spatial replacements, thereby accommodating the needs of tourists for dining, shopping, and entertainment [54,73]. | |

| C9: Accommodations | Repair and transformation of residential buildings to create suitable experiential and residential spaces for tourists [74,75]. |

| Facet | Facet Weight | Evaluation Index | Index Weight | Comprehensive Weight | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 Statuses of historic relics | 0.652 | C1 Completeness of historic relics | 0.548 | 0.357 | 1 |

| C2 Harmonization with surroundings | 0.158 | 0.103 | 3 | ||

| C3 Innovation degrees of transformation and utilization | 0.294 | 0.192 | 2 | ||

| D2 Basic environmental conditions | 0.179 | C4 Convenience of transportation | 0.236 | 0.042 | 7 |

| C5 Living conditions of inhabitants | 0.203 | 0.036 | 8 | ||

| C6 Comfort degrees of public spaces | 0.561 | 0.101 | 4 | ||

| D3 Degree of tourism development | 0.169 | C7 Sightseeing and tourism | 0.525 | 0.089 | 5 |

| C8 Dining and shopping | 0.188 | 0.031 | 9 | ||

| C9 Accommodations | 0.287 | 0.049 | 6 |

| Index | Fuma Lane (O1) | Dutian Temple (O2) | Hexia Ancient Town (O3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 Completeness of historic relics | Retained the historical styles and traditional street patterns of the Ming and Qing dynasties | About 200 years old | Retained architectural styles of the Ming and Qing dynasties |

| C2 Harmonization with surroundings | Disharmony between modern decorations and traditional street styles | Poor construction quality, diversified building forms, and disharmony with the style of the historic site | Loss of the authenticity of some historical buildings after repairs; harmonization and unification in style for most buildings |

| C3 Innovation degrees of transformation and utilization | Construction of new tourism distribution center and cultural exhibition center | Emergence of new tourist attractions based on the integration of Taoist culture and tourism | Repairing ancient buildings, demolishing old buildings, lacking features |

| C4 Convenience of transportation | Narrow streets, insufficient parking spaces, and inconvenient transportation | Narrow streets and uneven roads, impossible for motor vehicles to pass through | Retained traditional stone-paved roads, smooth traffic organization, and sufficient parking spaces |

| C5 Living conditions of inhabitants | Very old buildings, outdated infrastructure, and poor living conditions | Very old buildings, outdated infrastructure, and serious population aging | Inadequate preservation of dwellings |

| C6 Comfort degrees of public spaces | Insufficient public communication spaces, serious river pollution, disordered greening landscapes, and serious occupancy of public spaces | Lack of green landscapes and scattering of many low-efficiency, idle spaces | Clear rivers, beautiful green landscapes, and comfortable public spaces |

| C7 Sightseeing and tourism | Retained overall architectural styles of the Ming and Qing dynasties, which are characterized by blue bricks, black tiles, carved wooden windows, and ancient houses. Together with modern shops, the site offers rich experiences. | Presence of traditional architecture of the styles prevailing in the Ming and Qing dynasties, including religious architecture, former residences of celebrities, modern commercial relics, and numerous ancient dwellings | Profound cultural treasures, excellent tourism cultural resources, such as cultural customs, architectural arts, and folk customs |

| C8 Dining and shopping | Distributed with traditional gourmet food stores, coffee shops, and milk tea shops. Lack of diversity in types of businesses | Slow development of commerce and dining because only a small number of shops meet the daily living needs of residents | Distributed traditional gourmet food stores, photography shops, calligraphy and art shops, etc.; diversity in types of businesses |

| C9 Accommodations | Short tourist stays, lack of functions such as homestays | Mainly inhabited by locals; lacking functions such as homestays | Accommodations available around the scenic area |

| Evaluation Element | C1:C2 | C1:C3 | C2:C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of importance | 3:1 | 5:1 | 3:1 |

| Evaluation Element | C1 | C2 | C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| C2 | 1/3 | 1 | 3 |

| C3 | 1/5 | 1/3 | 1 |

| sum of columns | 1.533 | 4.333 | 9 |

| Evaluation Element | C1 | C2 | C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.653 | 0.692 | 0.556 |

| C2 | 0.217 | 0.231 | 0.333 |

| C3 | 0.130 | 0.077 | 0.111 |

| Evaluation Element | Weight |

|---|---|

| C1 | (0.653 + 0.692 + 0.556)∕3 = 0.634 |

| C2 | (0.217 + 0.231 + 0.333)∕3 = 0.260 |

| C3 | (0.130 + 0.077 + 0.111)∕3 = 0.106 |

| Facet | Evaluation Index | Comprehensive Weight | O1 | O2 | O3 | PI (O1) | PI (O2) | PI (O3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 Statuses of historic relics | C1 Completeness of historic relics | 0.357 | 0.205 | 0.413 | 0.382 | 0.073 | 0.147 | 0.136 |

| C2 Harmonization with surroundings | 0.103 | 0.237 | 0.302 | 0.461 | 0.024 | 0.031 | 0.047 | |

| C3 Innovation degrees of transformation and utilization | 0.192 | 0.406 | 0.334 | 0.260 | 0.078 | 0.064 | 0.050 | |

| D2 Basic environmental conditions | C4 Convenience of transportation | 0.042 | 0.239 | 0.177 | 0.584 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.025 |

| C5 Living conditions of inhabitants | 0.036 | 0.208 | 0.280 | 0.512 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.018 | |

| C6 Comfort degrees of public spaces | 0.101 | 0.262 | 0.141 | 0.597 | 0.026 | 0.014 | 0.060 | |

| D3 Degree of tourism development | C7 Sightseeing and tourism | 0.089 | 0.337 | 0.213 | 0.450 | 0.030 | 0.019 | 0.040 |

| C8 Dining and shopping | 0.031 | 0.280 | 0.132 | 0.588 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.018 | |

| C9 Accommodations | 0.049 | 0.160 | 0.223 | 0.616 | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.030 | |

| Value of PI | 0.266 | 0.308 | 0.426 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, X.; Chen, M.; Hsu, W.-L.; Dong, Z.; Lan, K.; Luo, H.; Lin, S.T.-H. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Evaluating Historic Sites in Huai’an Ancient Cities. Buildings 2023, 13, 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061385

Shen X, Chen M, Hsu W-L, Dong Z, Lan K, Luo H, Lin ST-H. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Evaluating Historic Sites in Huai’an Ancient Cities. Buildings. 2023; 13(6):1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061385

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Xijuan, Meng Chen, Wei-Ling Hsu, Zuorong Dong, Keran Lan, Haitao Luo, and Sean Te-Hsun Lin. 2023. "Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Evaluating Historic Sites in Huai’an Ancient Cities" Buildings 13, no. 6: 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061385

APA StyleShen, X., Chen, M., Hsu, W.-L., Dong, Z., Lan, K., Luo, H., & Lin, S. T.-H. (2023). Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Evaluating Historic Sites in Huai’an Ancient Cities. Buildings, 13(6), 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061385