1. Introduction

In the context of swift urbanization and the enlargement of administrative boundaries, certain areas that were once villages have undergone administrative transformations, evolving into unique “village-to-city areas”. This transition has introduced a set of challenges to the housing model, which was previously dominated by self-built houses. The dynamics of these areas, now designated as “village-to-city areas”, pose distinctive considerations as they navigate the shift from rural to urban structures and services.

As urbanization progresses and administrative boundaries expand, former villages undergo a transformation from rural to urban areas, surrounded by newly constructed collective housing. Simultaneously, factors such as city finances and the stage of development contribute to a slower pace of renewal in farm-to-house areas within county towns that have recently overcome poverty. Consequently, these areas may persist for a certain duration before undergoing comprehensive renewal.

Distinguished from conventional urban and rural regions, the term “village-to-community area” designates regions that have taken shape during the course of local urbanization, primarily due to the non-agricultural repurposing of land. This transformation leads to shifts in the economic and social makeup of these formerly rural areas [

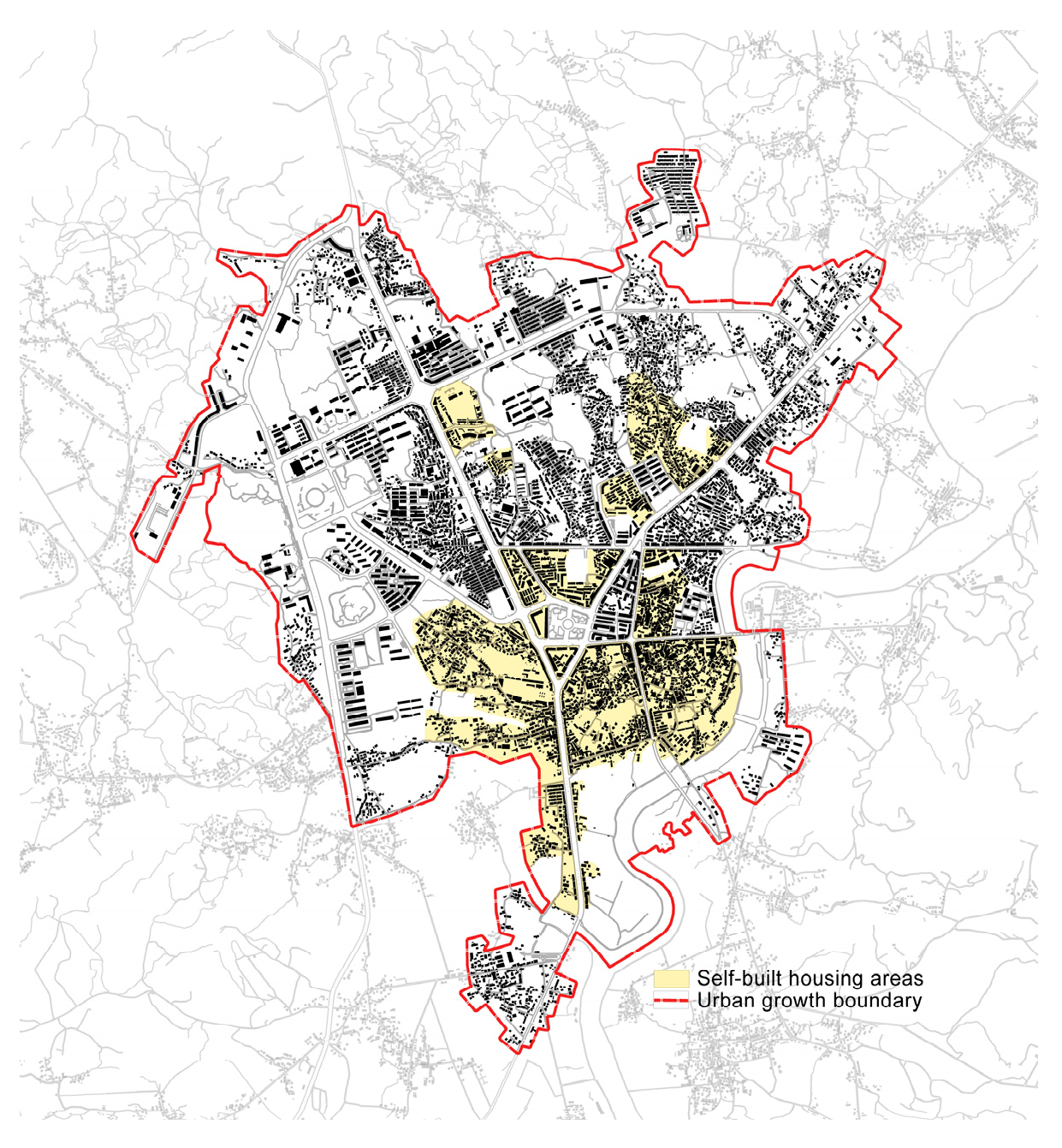

1]. In the context of this article, the term primarily pertains to areas where rural housing has not been relocated as a consequence of in situ urbanization, and self-built houses remain the dominant housing model. Some of these areas are situated in close proximity to the urban development boundary, while many still adjoin rural land. Therefore, it has a broader connotation than the familiar “urban village”.

The village-to-community areas straddle the line between urban and rural locations. In these areas, most, if not all, of the agricultural land has been requisitioned, and the residents’ identities have transitioned from rural to urban. The village committees have evolved into community committees, yet the living arrangements, lifestyles, and administrative practices still retain a semblance of traditional rural life. These areas are prevalent in the historical urban cores developed from villages within counties and the so-called “urban villages” on the outskirts of major cities. As economic development and urbanization continue to accelerate, the use of self-built houses for civilian purposes has undergone significant transformations, with self-built houses taking on increasingly commercial characteristics. However, these buildings carry inherent safety risks, making safety concerns a prominent issue.

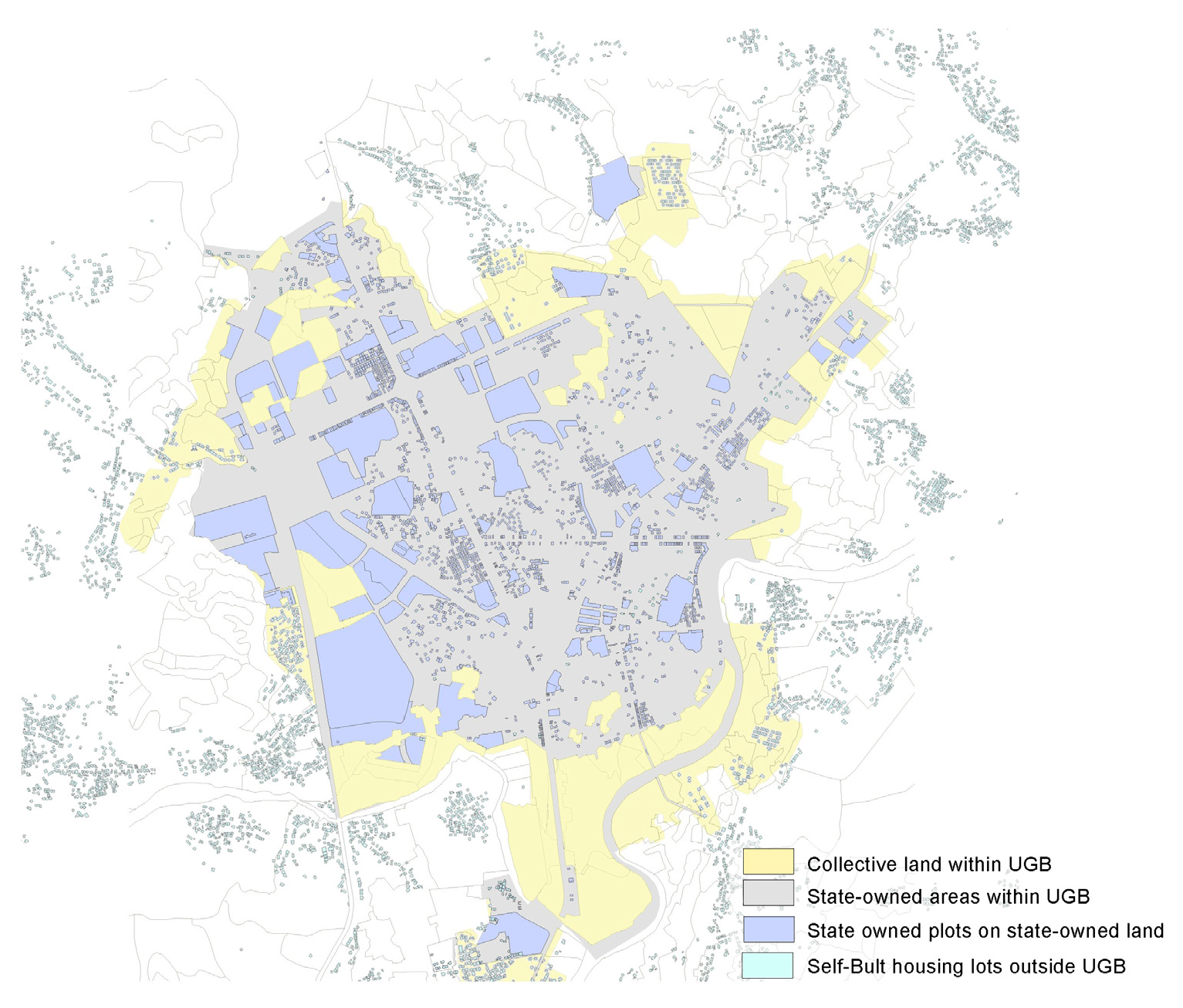

The ownership of land in village-to-community areas is complex and diverse. Self-built houses in the county can be divided into two types according to their land use nature. The land within urban construction areas is residential land, which belongs to the state. In principle, the homeowner has the property certificate and land use certificate. The land outside urban construction areas is homestead land, which belongs to the collective. It needs to be expropriated before it can be converted into state-owned land, which has a certain impact on the planning, construction, management, and environment of the city. The residential property rights in the self-built housing area are usually complex, involving various types of property rights, such as personal property rights, joint property rights, and collective property rights. This involves a large and complex population. The cost of redevelopment and construction after national expropriation is extremely high, and the challenges in policy guidance and control are numerous. At the same time, as a type of historical legacy residential land, self-built houses include the right to independent living, but with the increasingly prominent problems of urban land waste and the tightening of urban land resources, more and more cities are raising the threshold for obtaining land use rights or prohibiting the construction of self-built houses.

In the midst of China’s rapid urbanization, areas transitioning from rural villages to community spaces have emerged as a unique product of our time within Chinese cities. In some of these areas, self-built houses have become the prevailing housing model. This refers to residents constructing their own homes, which may encompass rebuilding on the original site, renovating and expanding, or building entirely new structures in different locations.

Self-built houses often lead to a variety of civil and administrative disputes and, in some cases, even serious criminal incidents. The elevated occurrence of safety incidents related to self-built houses within village conversion areas in recent years is a significant aspect of the spatial vulnerability in urban settings. A stark illustration of the challenges associated with self-built housing occurred on 29 April 2022, when an aged self-built residential structure in Changsha City collapsed, resulting in 53 fatalities. This tragic incident swiftly garnered widespread attention, raising significant concerns about the safety of self-built houses in densely populated areas, particularly in urban villages. Self-built houses used for commercial and service purposes, in particular, have exhibited lower safety standards and limited oversight.

However, the subsequent implementation of a “one size fits all” ban on self-building has also elicited concerns among scholars. To enhance the guidance for planning and constructing self-built houses, official safety inspections, planning guidance, and institutional constraints are imperative. Nevertheless, conducting safety inspections for self-built houses across China is currently challenging. Obtaining data on individual buildings—such as age, use, structural ratio, foundation condition, structural integrity, and instances of illegal demolition, alteration, and use—is problematic. The primary method for acquiring such data relies mainly on basic checks conducted by grassroots safety officers responsible for safety grids. However, the current organizational system of safety officers is imperfect, and the associated training for evaluations is inadequate. Additionally, due to financial constraints and varying stages of development, “village-to-city areas” in poverty-alleviated counties are less likely to undergo rapid renewal compared to cities in developed regions. Instead, projects may be implemented over an extended period, emphasizing the significance of an organic renewal process.

Housing development typically involves two main construction modes: speculative development and self-builds. Speculative development entails constructing houses without the commitment of users, based on the belief that there is demand for the space and that the houses will be rented out within a reasonable period after completion. Self-builds, on the other hand, broadly refer to any housing in which the first occupants are involved in the construction, encompassing both organization-built and self-built structures. Speculative development and self-builds represent formal and informal behaviors in housing construction, respectively. Self-builds are characterized by their bottom-up nature, distinguishing them from other-built or speculative housing, as well as collective housing, which is top-down.

The question arises: does the rationalization of self-builds still exist within the current urban planning context? Self-built housing can be viewed as a “bottom-up” approach to urban form generation. It is owner-driven, characterized by spontaneity and fragmentation, yet occurs at a scale that generates multiple and complex macro effects. Before liberation, the movement of plots was largely within property rights, with no combination of plots. The property rights and institutional environment were different. In an era of rapid urbanization, institutional intervention and regulation are crucial to prevent self-built housing from devolving into “slums” or becoming hotbeds of urban vulnerability.

In the British “Burgage Cycle” theory, the medieval burgage maintained the basic residential and industrial functions of a city during the period of the Black Death; this became an important cornerstone for the recovery and development of the city. However, during the Industrial Revolution, the peak of the Burgage Cycle, the burgage continued to support the progress of the city while producing a huge negative effect—environmental degradation. The burgage environments deteriorated, with high densities, poorly formed buildings, ill-conceived combinations, and mixed functions. Blind-backed houses inspired the infamous “back-to-back houses”, and the environment of the new workers’ settlements, influenced by the built form of the burgage, was the hardest hit during the cholera period of the 19th century (informality affecting formality). This forced the launch of public health campaigns and housing reforms in Britain, which in turn led to modern, integrated urban planning, urban planning and policies that promote the coherence of the four functions of the city—living, working, leisure, and transportation—through the empowerment of centralized and top-down social control legislation, the establishment of urban management systems and administrations from the central to the local level, and the optimization of technological innovations for the governance of the housing units. Thus, the “Burgage Cycle” plays an important role in the health, resilience, and security of cities.

Given this backdrop, it is imperative to intensify efforts to investigate and rectify safety hazards within self-built houses and enhance the supervision of building quality and safety. In light of these considerations, there is immense importance in conducting an analysis and summarizing the salient issues and potential solutions pertaining to the planning, construction, utilization, and oversight of self-built houses in areas transitioning from villages to community spaces. This paper is grounded in the research on “burgage theory” within the urban form theory of the Conzenian tradition. It formulates a framework for the revitalization of self-built houses, focusing on safety resilience in the transition from agricultural to residential areas in poverty-stricken counties. The paper aims to establish a mechanism for integrating and coordinating formal planning with informal self-built houses. Specifically, it is essential to identify existing challenges, systematically examine the mechanisms and strategies for renewal within a comprehensive management framework, and execute an organic renewal of self-built housing. The overarching goal is to progressively realize a safe and resilient development model.

Section 2 of this paper provides a comprehensive review of both domestic and international theories and practices related to self-built houses in village resettlement areas. In

Section 3, the main methodology employed in the study is introduced.

Section 4 establishes a framework for the renewal of self-built houses in village conversion areas, emphasizing security resilience. Moving forward,

Section 5 utilizes Lianhua County as a case study, examining the historical evolution of the local city, current land property rights, and the distribution of self-built houses, particularly in the county city area that has undergone poverty alleviation. In

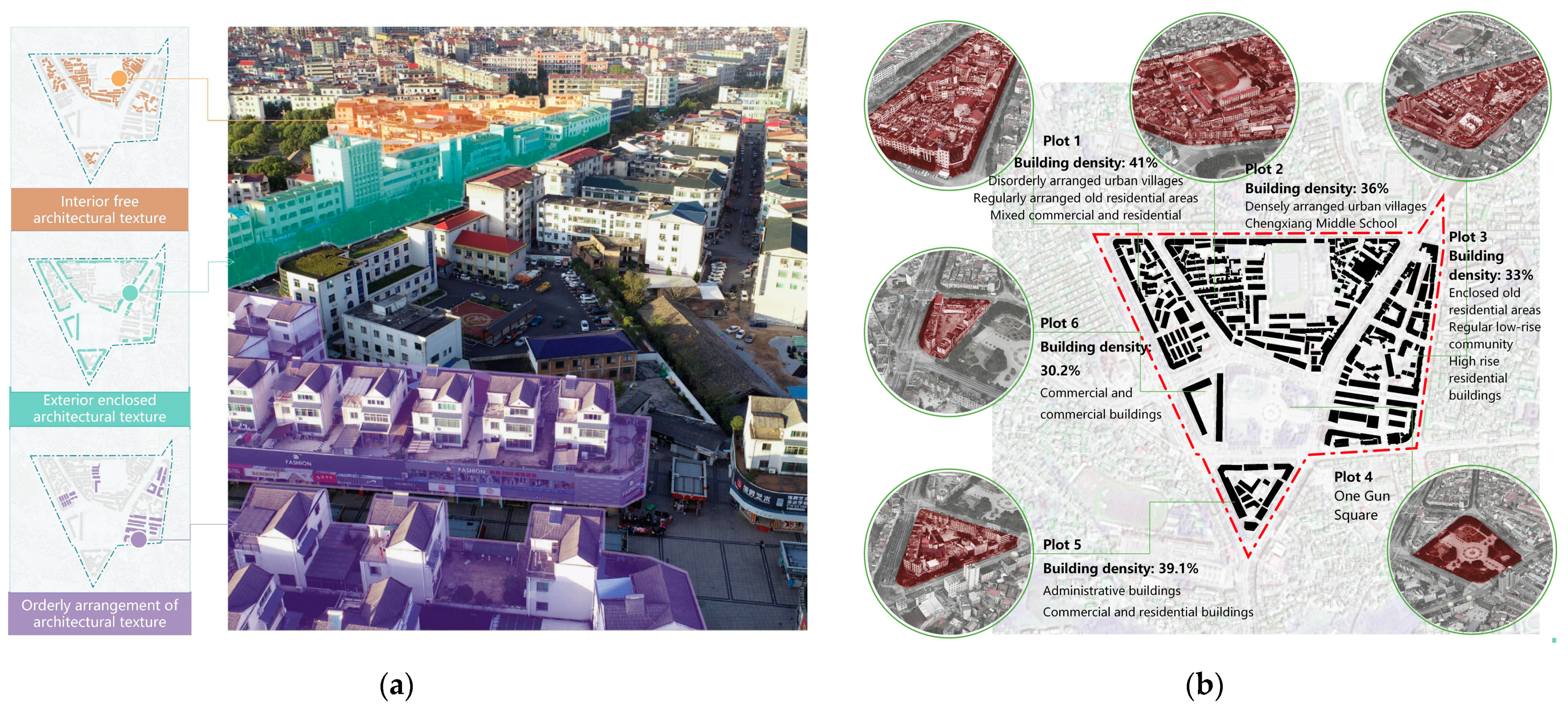

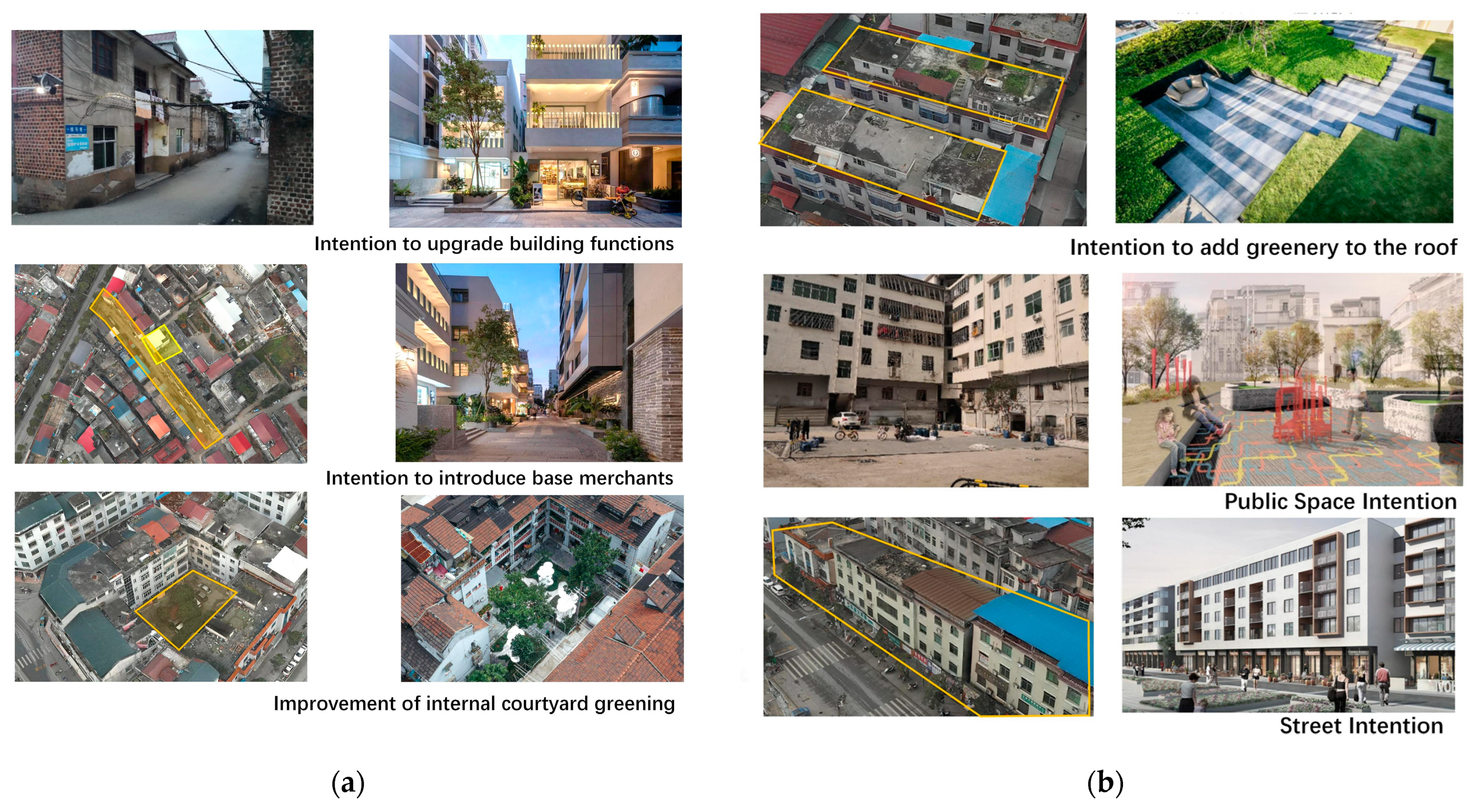

Section 6, a detailed analysis and investigation of the problems and underlying issues in self-built housing areas are conducted through investigation of the current situation. Building upon a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing safety in self-built housing, the section clarifies planning objectives and value orientation. It advocates for hierarchical and classified planning and construction controls tailored to local conditions. An orderly updating of the planning process is proposed to enhance the safety of self-built housing areas.

Section 7 delves into a literature review to discuss and reflect on the findings, highlighting the innovative aspects of the study and its significance for future research, industry, and policy makers.

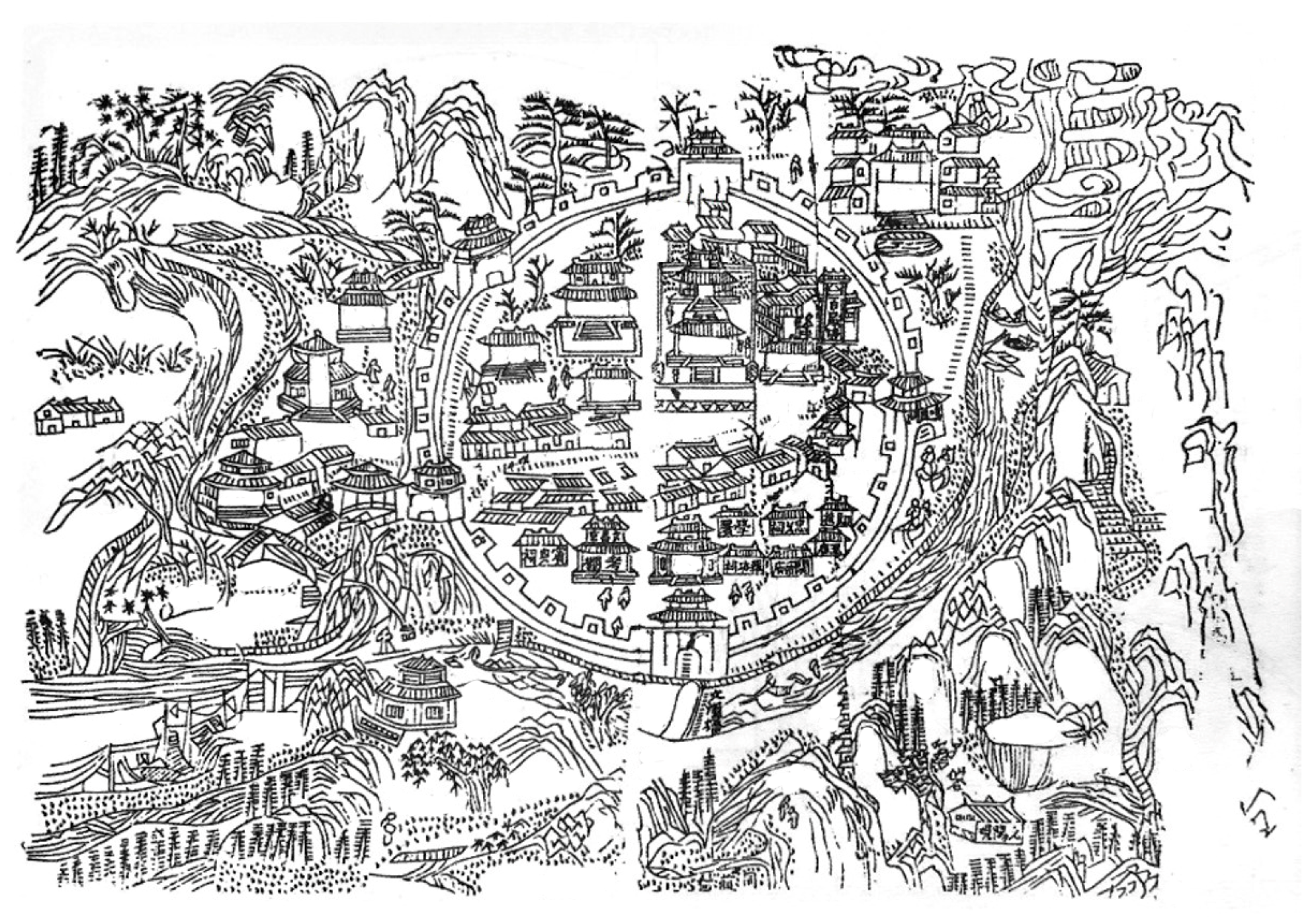

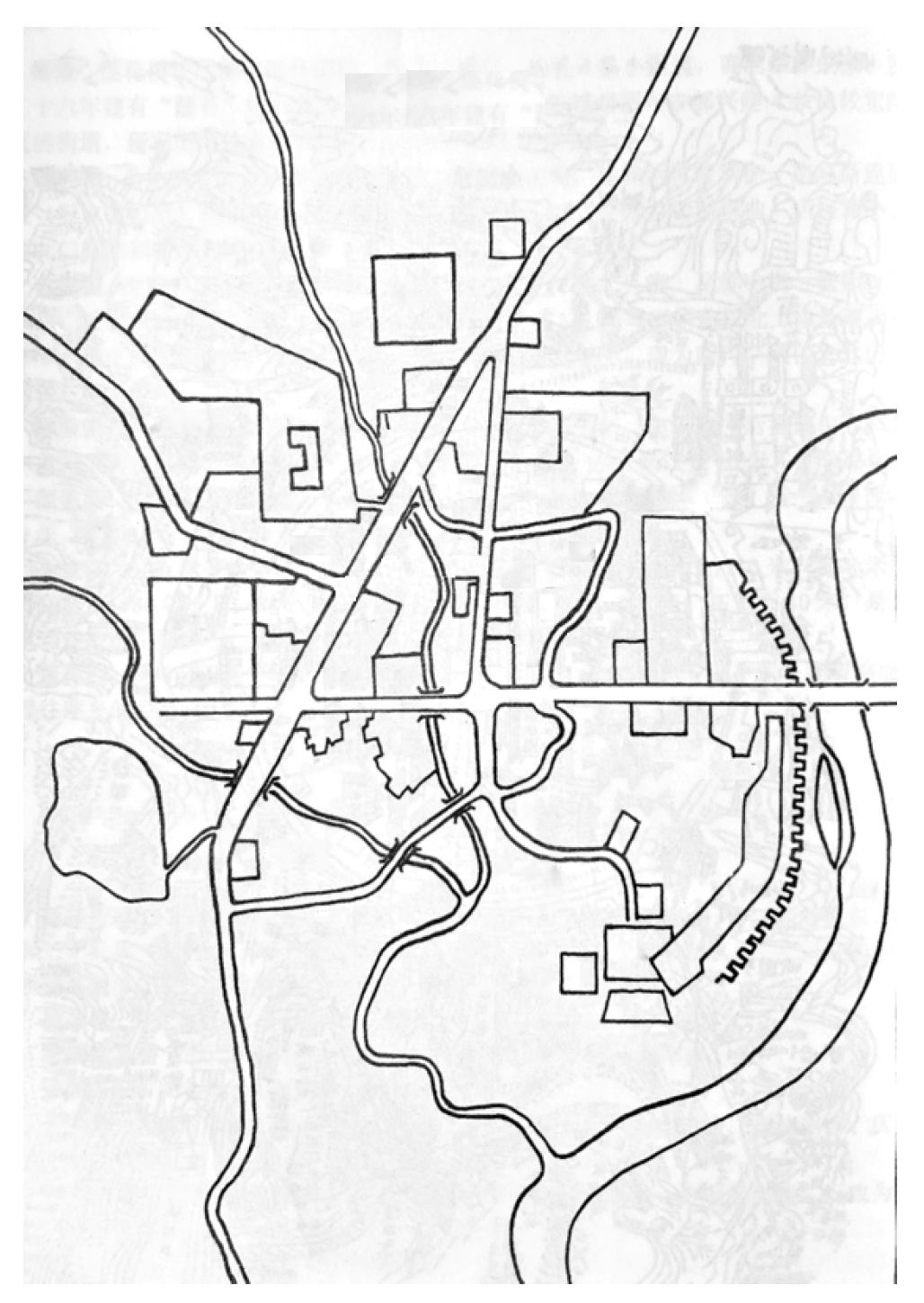

In 2019, Lianhua County in Pingxiang City, Jiangxi Province, successfully shed its designation as a poverty-stricken county, ushering in the dual responsibilities of “enhancing urban functions” and “elevating urban quality”. Lianhua County serves as a representative case for numerous counties that have overcome poverty, reflecting the broader context of the early and middle stages of urbanization in China. Particularly relevant to counties that have recently emerged from poverty, this study is poised to contribute valuable insights and policy recommendations with potential applicability nationwide. By focusing on the renewal of self-built houses in Lianhua County, the study systematically explores planning, construction, and governance strategies, offering a comprehensive reference for decision making by relevant government departments.

This paper selects the planning and construction of self-built houses, a prototypical form of informal housing, as the focal point for community vulnerability research. The choice of research object is innovative, providing a unique perspective. Moreover, this study represents a cross-disciplinary and integrative approach, incorporating community planning theory, urban governance theory, planning decision-making theory, and resilient city theory. This interdisciplinary approach contributes to knowledge updating and refinement within each field, fostering a comprehensive understanding of community vulnerability and resilience.

2. Literature Review

The Burgage Cycle in the UK, a foundational concept in urban morphology within the Korn School, encompasses three dimensions: time, space, and people. The term “Burgage” refers to medieval land, where lords divided their urban land and rented it to citizens. Unlike rental properties, burgage involves renting of the land, not the house. This form consisted of long, narrow strips of land along a street, with houses facing the street. The city and the burgage were pivotal platforms for the decentralization and transfer of power. Cities gained autonomy through charters, while citizens obtained tenure of the burgage through deeds [

2].

The “Burgage Cycle” was a historical process involving the construction and demolition of burgage houses, spanning from the middle ages to the Industrial Revolution. Urbanization, viewed as a self-regulation process of housing supply and demand by the people, represents a significant transfer of power from the “top down”. The Burgage Cycle, unchecked by the government, shaped the character and destiny of urban development. It corresponds to key historical epochs, including the Agricultural Revolution, Commercial Renaissance, and the Functional Industrial Revolution, occurring only once. After completing the cycle, the burgage areas become “urban fallow”, cleared for new development, such as commercial development, within the context of urban renewal.

The “Burgage Cycle” plays a crucial role in the health, resilience, and safety of cities. The positive effects included the medieval burgage sites serving as vital residential and industrial anchors during the Black Death, contributing to urban recovery and development. However, there were negative effects, notably during the Industrial Revolution, which marked the culmination of the burgage land cycle and had significant adverse impacts, such as environmental degradation, despite supporting urban progress [

3].

Although self-building practices are not predominant globally, they play a crucial role in addressing housing challenges for individuals with lower to middle incomes. Self-building initiatives contribute to the exploration of zero-carbon homes, the development of sustainable communities, the enhancement of marketplace diversity, and the improvement of housing affordability. These positive aspects can be further reinforced through the establishment of a more uniform and equitable post-build registration system. The study by Daniël B. et al. (2018) highlights the dominance of public authorities in formal housing, contributing to housing market inequities. The authors propose increased public participation, especially from lower- and middle-income residents, in self-building initiatives to address these inequalities [

4]. Emma H. (2020) emphasizes the suitability of group self-builds as a model for delivering zero-carbon homes, sustainable communities, and affordable housing [

5]. Grace S. (2021) advocates for the improvement of self- and custom housebuilding to enhance market diversity, increase housing affordability, and promote sustainable homes. She suggests that addressing uncertainty requires implementing a more consistent and fair system, including supplementary planning guidance documents and a robust support system for approval applicants [

6].

4. Framework for Planning and Construction of a Self-built House—Ensuring Safety and Resilience

4.1. Orientation: Prioritizing Livelihood and Emphasizing Safety

The planning and construction of self-built housing areas should align with the overarching objectives of urban development and adhere to relevant benchmarks set forth by the national county-level civilized city evaluation system. The following key considerations should guide this process: (i) strengthening functions: enhance the road network system to alleviate traffic congestion points; increase the availability of parking facilities; improve the overall quality of transportation infrastructure; enhance municipal support facilities, including optimizing drainage systems, improving fire safety infrastructure, and refining the layout of environmental sanitation facilities; (ii) enhancing livelihood: optimize the layout of education and medical facilities; create and maintain green spaces and parks; elevate the quality of cultural and sports amenities.

Building upon the foundation of bolstering functions and improving livelihood, the planning and construction of self-built houses should place additional emphasis on the standards of resilience, governance, and safety. This entails (i) enhancing resilience, which involves developing mechanisms for monitoring, early warning, and management of public health emergencies, contributing to the area’s resilience; (ii) emphasizing governance by strengthening the construction of community governance and service systems to foster a cohesive and well-managed community; (iii) ensuring safety by implementing stringent safety assessments for housing structures, addressing hazardous structures promptly through effective governance and management, developing emergency response and disposal protocols, and introducing rigorous oversight and management measures to maintain safety standards. By adhering to these principles, the planning and construction of self-built housing areas can not only promote functional and livable communities but also cultivate resilience, effective governance, and safety, ensuring a high quality of life for residents.

4.2. Framework: Safety Assessment and Transitional Support

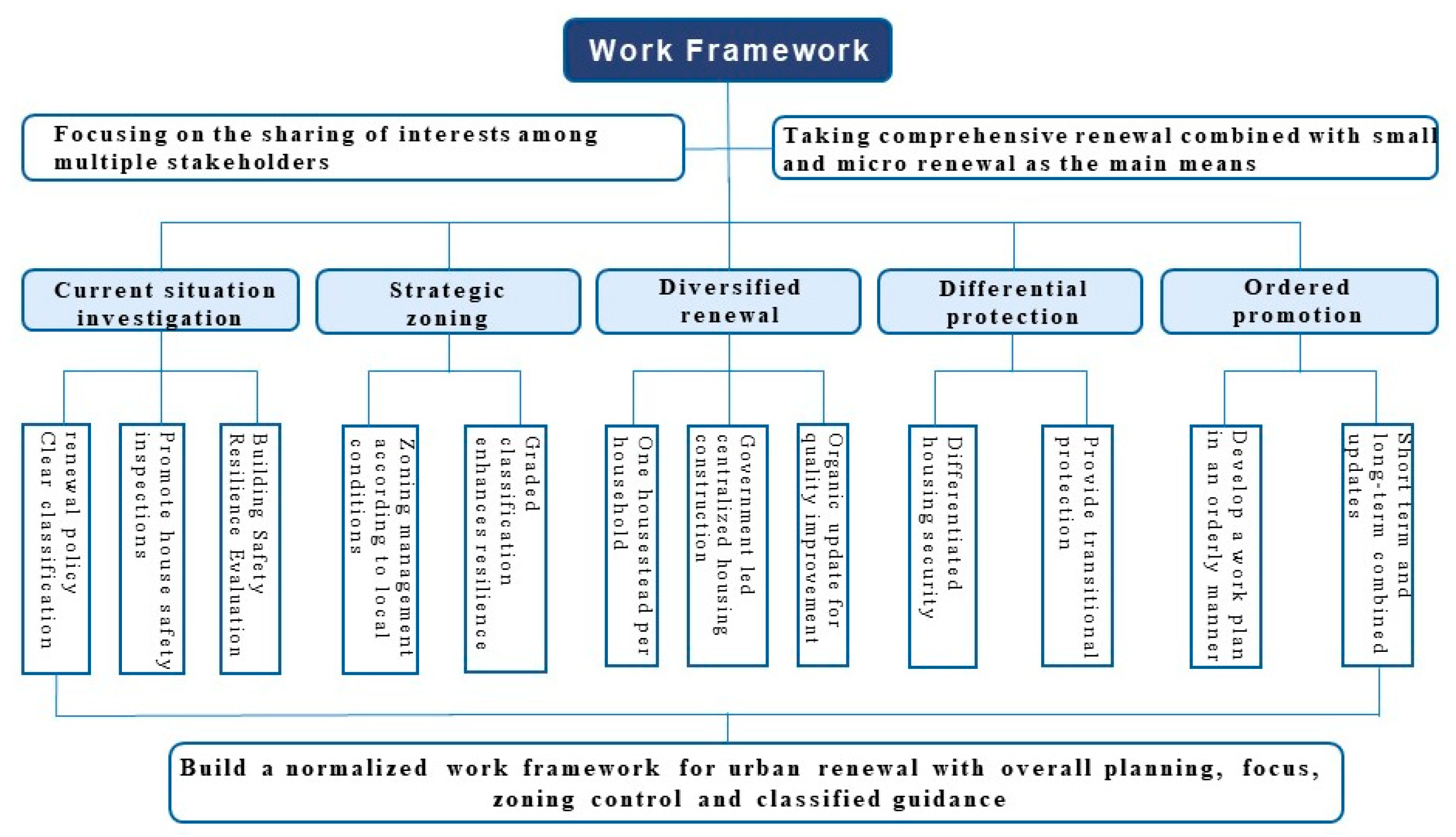

This paper delves into the planning and construction approach for self-built housing areas through a comprehensive process that includes current situation assessment, strategic zoning, diversified renewal, differentiated protection, and orderly progression. The objective is to establish a standardized framework for urban renewal characterized by comprehensive planning, focused priorities, zoning control, and categorized guidance (as depicted in

Figure 1). Central to this framework is the core principle of aligning the interests of various stakeholders. The primary method encompasses a holistic renewal strategy complemented by micro-level renovations. This strategy aims to facilitate the reconfiguration of regional space, stimulate industrial advancement, optimize population distribution, enhance governance practices, and preserve the cultural heritage of self-built housing areas. By embracing this framework, the planning and construction of self-built housing areas endeavor to harmonize the interests of all parties involved, instigate comprehensive renewal efforts, and encourage micro-level enhancements. This approach seeks to foster positive changes in regional space, stimulate industrial growth, optimize population distribution, enhance governance practices, and safeguard the cultural legacy of self-built housing areas.

This comprehensive framework for the planning and construction of self-built housing areas comprises the following key components: status quo investigation, policy requirement, promotion of housing safety inspections and transitional support for hazardous renovations, strategic zoning, diversified renewal, differentiated institutional supports, and scheduled promotion.

4.3. Status Quo Investigation

Responsible departments should enhance their information management systems to facilitate a comprehensive investigation into housing safety. This investigation should accurately depict the baseline conditions of self-built houses and the surrounding areas, serving as a valuable reference for government decision making.

The formulation of annual work plans and relevant urban development strategies is essential. Strengthening planning and construction management efforts and the introduction of specific policies and measures should be tailored to the specific circumstances.

4.4. Policy Implementation Requirement

It is imperative to establish a policy for renewals based on an evaluation of the current situation. In alignment with seismic and fire protection planning objectives for construction, it is essential to institute a comprehensive building safety and resilience evaluation index system. The specific components encompass planning layouts, building units, facilities, equipment, site environment, and safety governance. Through a comprehensive assessment of construction scenarios, including super-high-rise buildings, cultural heritage sites, heritage conservation units, older structures, and rural residences, measures to enhance housing construction resilience within the planning region can be explored. Systematic promotion of the renovation and transformation of housing construction should be undertaken to bolster the resilience of urban housing construction (see

Table 1). Based on the current status of building safety and resilience, we propose a “targeted” and “multistep” renewal strategy. This allows a transition from spatial transformation to connotation and quality enhancement through the introduction of industry functions, upgrades in service support, and improvements in the human settlement environment, all while optimizing the manifold values of the urban system.

4.5. Promotion of Housing Safety Inspections and Transitional Support for Hazardous Renovations

It is imperative to advance safety inspections for housing and provide transitional assistance for hazardous renovations. In cases where there are residential safety concerns arising from precarious dwellings within the confines of urban development, these issues should be promptly assessed and verified by certified housing safety appraisal institutions. Before embarking on complete demolition and reconstruction projects, residences situated within the urban development limits that meet the “one household, one house” criteria and have been categorized as Level C or D hazardous structures can opt to seek temporary housing solutions. These can be in the form of applying for public rental housing or rental subsidies from the housing department based on their specific circumstances. This is to ensure the short-term resolution of their housing predicaments. Houses that have been conclusively deemed hazardous by certified housing safety appraisal institutions and pose a substantial threat to public safety, especially if they represent the sole residential property within the county development boundaries, will be subject to purchase by the county government.

4.6. Strategic Zoning

At the planning level, it is imperative to identify critical areas and explore opportunities for optimizing spatial structures. Urban renewal zones should be categorized based on assessments of their renewal potential, with options encompassing the maintenance of the existing state, comprehensive renewal through functional transformations and reconstruction, small-scale renewals, partial renewals via functional changes, ecological and landscape enhancements, and comprehensive land improvements.

4.7. Diversified Renewal

The selection of various regeneration models should be informed by the specific conditions of each area. Options include building one house per rural household, centralized construction, a combination of demolition and renewal, and organic regeneration. For areas situated beyond the urban development boundary, a combination of individual and centralized construction is recommended, adhering to the one house per household principle and encouraging centralized construction. Within the urban development boundary, the primary approach should be centralized resettlement construction, supplemented by residents’ self-construction and other methods, including organic renewals.

4.8. Differentiated Institutional Supports

Prior to the initiation of complete demolition and reconstruction efforts, tailored residential protection measures should be implemented based on local conditions, zoning management, and synchronized progress. Transitional institutional support should be provided to relevant rights’ holders for households meeting the “one household, one homestead” requirement and whose houses have been designated as Level C or D dangerous buildings.

4.9. Scheduled Promotion

The renewal process should be carried out through defined projects with clear timelines. Work plans and urban development strategies should be developed in an organized manner, with a focus on safety, usability, cost-effectiveness, and aesthetic considerations [

11]. Aspects such as housing quality and safety, fire and disaster prevention design, public service facilities, green spaces, and road infrastructure should be prioritized. Collective land in the central city area requires specific measures to ensure efficient renewal projects. The renewal timeline should incorporate both near and distant future considerations, with a planned promotion approach emphasizing near-term implementation.

By following these comprehensive principles, the planning and construction of self-built housing areas can be conducted in a systematic and effective manner, ultimately enhancing safety, livability, and overall community well-being [

12].

7. Discussion

This paper serves as a decision support tool for advancing the planning, design, construction, and management of self-built housing. It offers a crucial resource for decision-makers involved in the renewal of self-built housing areas, providing the means to promptly analyze problems in planning and construction. The proposed countermeasures aim to promote the development of urban resilience. The case experience from Lianhua County sets a paradigm for government-led community renewal of self-built housing, contributing to the evolution of community housing construction in Chinese cities. Drawing from comprehensive studies domestically and abroad, it is evident that guiding residents’ self-building behaviors through legal and technical norms, while moderately encouraging these behaviors with improved systems, is the fundamental solution to the problem. Despite the issuance of the Residential Building Code GB 50368-2005 [

24] by the Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China in 2005, the binding effect of the norms is virtually null and void for self-built houses on residents’ residential land due to the lack of a whole-process approval mechanism [

25].

In the course of drafting this article, the local government of Lianhua County issued pertinent policy documents. These include the “Implementation Measures for Collective Land Acquisition and Compensation and Resettlement in Urban Areas of Lianhua County” and the “Implementation Measures for Compensation and Expropriation of Houses on State-owned Land in Lianhua County”. These measures aim to regulate the processes of collective land acquisition, compensation, and resettlement, as well as the compensation and resettlement procedures for houses on state-owned land. Additionally, the government released the “Measures for the Management of Residents’ Building in Lianhua County”, which is designed to govern the management of residents’ buildings and ensure the smooth implementation of urban and rural planning. The policy measures for the construction of apartments for new citizens in villages converted to residential areas involve several key principles: Prohibition of Individual Construction: Individuals are prohibited from building houses within the control line of the urban development boundary, and approval for residence bases is no longer granted. Unified Planning and Reconstruction: The construction mode emphasizes unified planning, centralized piecemeal reconstruction, and centralized resettlement, commonly referred to as “new citizens’ apartments”. This approach aims to gradually eliminate urban villages and land (residence bases) within cities. “Safeguard Mode”—Households with a Home: The policy adopts a safeguard mode known as “households with a home”, ensuring that residents have access to secure housing. Reserving Industrial Premises: In areas where the construction of apartments for new citizens takes place, industrial premises may be reserved to promote the development of the village’s collective economy in alignment with national policies and regulations. Land Reserve: The land vacated by the construction of new citizens’ apartments will be unified and controlled by the land reserve department. Phased Municipal Utilities Planning: Municipal utilities within the land area of the new citizens’ apartments are planned and constructed in phases, synchronized with the construction of the project. Compensation for Expropriation: In cases where residents’ houses need to be expropriated for the construction of the New Citizens’ Apartment, the compensation for expropriation includes monetary compensation and the exchange of house ownership rights, provided through two distinct methods.

These policy measures collectively aim to regulate and guide the transformation of villages into residential areas while addressing issues related to individual construction, promoting economic development, and ensuring fair compensation for affected residents. The predominant self-built housing policy of the local government currently involves a gradual renewal approach through compensation and exchange. The key focus is on the phased elimination of individual houses constructed within the control line of the urban development boundary. This policy signifies a strategic effort to manage and transform self-built housing in the region, aligning with urban planning objectives and fostering organized development in line with regulatory frameworks.

A comprehensive review of the international literature on self-built housing reveals that, despite certain incentives in countries like the UK and the Netherlands, the practice is still in an exploratory and experimental phase. The primary goal is to alleviate housing pressure, particularly in the affordable housing sector. In these countries, the Burgage Cycle has evolved to the present day, emphasizing the ongoing importance of formal urban planning and regulated housing construction for creating a livable environment. Nevertheless, the positive effects of spontaneous construction at the outset of the Burgage Cycle cannot be dismissed. Permitting controlled self-construction under official supervision, allowing for a degree of “self-growth”, could contribute to the resilient and healthy development of cities.

8. Conclusions

The safety concerns associated with self-built houses in rural areas, particularly those used for production and operations, have escalated in China. This escalation can be attributed to the absence of proper planning, design, and standardized regulations for self-built houses. The result is a range of significant problems in the planning and construction of these houses, including disorganized functional layouts and haphazard spatial structures. Furthermore, the absence of standardized constraints has led to subpar construction techniques. In addition, there is a widespread disregard for the usage rules of self-built houses, inadequate legal standards, and a lack of supervision. These factors have compounded maintenance issues and have heightened the risk of regional disasters.

Drawing on field research and the relevant literature from Lianhua County, Jiangxi Province, this article underscores the importance of setting planning objectives that prioritize the well-being of residents and emphasize safety. It advocates for a core value orientation based on “resilience, governance, and security”, with an emphasis on balancing the interests of various stakeholders. The article proposes a comprehensive approach to spatial adjustment in self-built housing areas, industrial upgrades, population optimization, governance enhancements, and the preservation of cultural heritage, with particular attention given to the transformation of self-built housing in village-to-community areas.

This study explores a structured approach to planning and constructing self-built housing areas through methods such as current situation assessment, strategic zoning, diversified renewal strategies, differentiated protection measures, and systematic promotion. It aims to create a standardized framework for urban renewal, which accounts for the overall situation, highlights key areas, manages various zones, and guides classification. The key points are as follows: Conduct a comprehensive assessment of safety and housing quality within the jurisdiction, capturing a precise understanding of the state of self-built housing and defining a policy for classified renewals. Promote house safety inspections and provide transitional safeguards for hazardous building transformations. Implement relevant planning and zoning management practices that are tailored to local conditions. In areas outside the urban development boundary, encourage a combination of individual and centralized construction methods, while emphasizing one household, one house, as well as centralization. Within the urban development boundary, prioritize centralized resettlement construction, with residents’ self-built housing as supplementary. Promote various forms of organic renewals. Enhance the guidance of differentiated zoning policies and approach land resource renewal in a classified manner, focusing on “priority differentiation and precise policies”. Promote diversified renewal methods tailored to local conditions. Implement differentiated residential protection for homesteads and self-built houses in conjunction with zoning management, outlining construction methods such as one household, one house, centralized construction, demolition and transformation, and organic renewals in rural areas. Promote the implementation of plans in an organized manner by specifying the details of renewals and their timing. Categorize plans by function and focus on improving environmental quality through block-unit combinations. Finally, this article employs the example of self-built housing around Yizhiqiang Square in Lianhua County to illustrate the implementation of organic renewals for residential and commercial self-built housing transformations. Additionally, with regards to the use and regulation of self-built houses, the following are recommended: Clarify the responsibilities of government departments and enhance their performance. Actively engage social forces to ensure the quality of self-built houses. Strengthen safety production awareness and improve residents’ safety consciousness. Bolster the construction of laws and regulations to enhance the legal framework for construction management.

This article offers a systematic exploration of China’s planning, construction, and governance strategies for self-built houses based on research in Lianhua County. It serves as a valuable reference for decision makers in relevant government departments. Future research endeavors include in-depth studies and analyses of the safety resilience evaluation system for self-built houses and an urban renewal potential assessment system based on multiple data sources. Moreover, this article, while focusing on some areas of Lianhua County, Jiangxi Province, has relevance for poverty-alleviated county towns. Future plans include supplementing case studies of different scales, such as second-tier cities and small or medium-sized cities, to offer tailored decision-making recommendations for government authorities.

This paper offers a resilient perspective on the delicate balance between formal and informal housing construction during the global urbanization process. While issues related to land ownership and housing systems may not be as pronounced in countries with predominantly private land ownership, rapidly urbanizing nations that rely on a different land ownership system may encounter similar challenges.

Spatial changes based on ownership plots are a widespread phenomenon in both China and abroad, exhibiting distinct characteristics in various institutional environments. Examples include the transformation from traditional courtyard houses to larger, mixed courtyards in Beijing, the evolution of bamboo houses to substandard bamboo houses in Guangzhou, and the progression from British courtyards to semi-slums. Each of these transitions has significantly influenced the local urban morphology.

Recognizing and respecting the underlying laws governing these spatial changes and innovating planning and design methods are crucial approaches for the renewal of self-built houses. The evolution from the historical “Burgage Cycle” to the regeneration of historic districts (bridging the past and present) and further to the development of “village-to-community” areas (linking urban and rural domains) signifies a new type of Burgage Cycle, which is notably shorter and can occur at any time, particularly in urban fringe areas.

However, the approach to bottom-up self-built housing varies in different countries. Currently, the UK and the Netherlands continue to encourage bottom-up self-built housing, while in China, such practices are universally prohibited within urban planning areas. In rural areas of China, self-built housing is permitted on homesteads. Considering the Burgage Cycle theory and its theoretical explanation of the “informality” of self-built housing construction, there is a need to explore the optimal timing and appropriate practices for the “formal” behavior of governmental agencies in future studies.