Abstract

The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) property of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is undesirable because of the insufficient active edge sites and the poor conductivity. To enhance HER performance of MoS2, nickel phosphide (Ni2P) was combined with this catalyst and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids (38 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-38, 50 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-50, and 58 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-58) were fabricated via a hydrothermal synthesis process. Morphologies, crystallinities, chemical components, specific surface areas, and HER properties of the fabricated MoS2/Ni2P samples in an alkaline electrolyte were characterized and tested. In addition, the insight into the HER properties of as-prepared catalysts were revealed by the density functional theory (DFT) calculation. Additionally, the stabilities of pure MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/Ni2P-50 samples were evaluated. The results show that the addition of Ni2P can enhance the HER property of the MoS2 catalyst. Although HER properties of the above-mentioned three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids are inferior to that of pure Ni2P, they are much higher than that of MoS2. Among as-prepared three hybrids, MoS2/Ni2P-50 exhibits the best HER performance, which may be due to its uniform morphology, large specific surface area, and excellent stability. The MoS2/Ni2P-50 hybrid shows a high cathodic current density (70 mA/cm2 at −0.48 V), small Tafel slope (~58 mV/decade), and a low charge transfer resistance (0.83 kΩ·cm2).

1. Introduction

With growing concerns about environmental pollution and energy crises resulting from overconsumption of coal and fossil fuels, the exploitation of renewable clean energies, such as solar energy, wind energy, hydraulic power, biological energy, fuel cell, and hydrogen energy come to the forefront [1,2,3]. Among the clean energies mentioned above, hydrogen energy is attracting ever-growing attention due to the convenient production and effective cost [4,5]. Apart from the traditional method through steam from fossil fuels, the process of electrochemical water splitting is considered as an alternative to produce hydrogen through the HER [6,7,8,9]. Until the present, the well-known platinum and platinum-based alloys show the best electrocatalytic performance for HER [10,11,12,13]. However, their high-cost and scarcity impede their wide applications in practice [14,15,16].

To facilitate HER application, it is urgent to develop low-cost alternatives with Earth-abundant and cost-effective features to replace the noble metals [17,18]. Thus, various non-noble materials including transition metal sulfides [19], selenides [20], oxides [21], carbides [22], and nitrides [23], as well as phosphides [24], have been reported as electrocatalysts for HER. Among these catalysts, MoS2-based materials have been researched as the promising substitutes owing to their low cost, Earth-abundance, and the relatively high activity [25,26]. However, the inert basal surface, poor intrinsic conductivity, and insufficient edged activity sites limit their HER performance [27]. In order to enhance the HER performance of this catalyst efficiently, a large number of efforts have been devoted and can be briefly classified as follows [4,28,29]: (1) increasing the density of active edge sites; (2) enhancing the inherent activity; (3) improving the electrical contact between active sites. Generally, intensive endeavors such as interlayer intercalation [30,31], phase transformation (from 2H-MoS2 to 1T-MoS2) [32], gentle oxidation [33], functional structural design [34], and stabilizing the edge layers with organic molecules [35] have been made to increase the active sites located at the edge, whereas the basal plane is still chemically inert.

Additionally, for the purpose of improving the electrical contact between active sites of MoS2, various promoters, such as gold [30], platinum [36], palladium [37], carbon materials [38], core-shell MoO3 [39], Co3O4 nanosheet array [40], graphene [41,42], graphene oxide [17,43], and nickel-phosphorus (Ni-P) powders [4], have been adopted as electrical conduction-enhancing supports. Of all the above-mentioned supports, the cost-effective Ni-P powder possesses superior electrical conductivity and outstanding HER performance [28,44,45]. Thus, this material is a suitable candidate employed to enhance the HER activity of MoS2. In view of the fact that Ni-P incorporation is advantageous to the enhancement in the HER property of MoS2 [4], herein, it should be worth noting that the coexistent nickel phosphide phases (i.e., Ni5P2, Ni2P, Ni3P, Ni12P5, NiP2, Ni5P4, NiP, and Ni7P3) [46] will play a major role in HER feature of this catalyst. Among these nickel phosphides, Ni2P demonstrates an excellent HER characteristic [14,47] and draws tremendous attention. Although the attempt of incorporation of Ni2P on to the surface of nano-MoS2 has been made in the hope of the increment in HER performance [16]; to the best of our knowledge so far, the effort of Ni2P employed as a sublayer support to improve the HER property of MoS2 is insufficient. In this sense, the role of Ni2P as a layer support in pursuit of the increase in MoS2 HER deserves to be investigated.

Unambiguously, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations as a major supplement to experimental techniques will be significantly valuable for revealing the intrinsic feature of HER [30,42,48,49,50]. Atomistic details related to the adsorption and desorption of hydrogen atoms, as well as the immanent interaction between hydrogen atom and the catalyst can be perfectly interpreted. To date, some studies in HER process for MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/graphene catalysts have been reported [42,49,50], but efforts related to that of MoS2/graphene hybrid catalyst via the DFT simulation are insufficient.

In this work, MoS2 was anchored on the surface of the Ni2P nanosheet via a hydrothermal synthesis process, and the three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids (38 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-38, 50 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-50, and 58 wt % Ni2P addition for MoS2/Ni2P-58) were fabricated. The aim of this study is to offer an effective route to improve the HER property of MoS2 by combining of this metal sulfide with Ni2P. Morphologies, crystallinities, chemical components, and active areas of the prepared MoS2/Ni2P hybrids were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. Techniques of linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), Tafel polarization, cyclic voltammetry (CV), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were employed to test HER properties of the above three hybrids; subsequently, the effect of Ni2P as the bottom substrate was illustrated. Additionally, the adsorption energies (ΔEads) and the Gibbs free energies of adsorption (ΔGads) between the hydrogen atoms and the catalyst were calculated. Furthermore, the stability of the hybrid was evaluated.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Material

Analytical grade reagents of ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate ((NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 99 wt %), thiourea (CH4N2S, 99 wt %), red phosphorus, nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2·6H2O, 98 wt %), potassium hydroxide (KOH), and absolute ethanol were purchased from Jingchun Scientific Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The 5 wt % of Nafion solution was offered by Alfa Aesar Chemicals Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The Pt/C power (20 wt % Pt on Vulcan XC-72R) was supplied by Yu Bo Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). In this present study, all above reagents were used as received in the present study and without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis of the Ni2P Nanosheet

Under vigorous stirring condition, 1.63 g red phosphorus and 1.25 g NiCl2·6H2O were dissolved in 15 mL deionized water for 30 min and a slurry-like mixture was obtained. Then this mixture solution was transferred into a 25 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and followed by placed into a muffle furnace (WRN-010, Eurasian, Tianjin, China), which was preheated to 180 °C. The hydrothermal synthesis process was carried out at 180 °C for 24 h. When the temperature of the muffle furnace was cooled to room temperature naturally, the formed particles were separated by centrifugation and washed with ethanol twice and deionized water three times. Lastly, the fabricated gray-black Ni2P powders were dried in a vacuum oven (DZF-6050, Boxun Industrial Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) and retained for use.

2.3. Synthesis of the MoS2/Ni2P Hybrids

A total of 1.41 g (NH4)6Mo7O24∙4H2O, 0.26 g CH4N2S and three different amounts of Ni2P (38 wt %, 50 wt %, and 58 wt %) were dispersed in 20 mL of distilled water. The mixture solution was vigorously stirred for 1 h at room temperature. After that, the solution was transferred into a 25 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave placed in a muffle furnace, and then reacted at 200 °C for 24 h. As the solution temperature was cooled to room temperature naturally, the resultant three black samples (MoS2/Ni2P-38, MoS2/Ni2P-50, and MoS2/Ni2P-58) were centrifuged and adequately washed with ethanol and deionized water. Finally, the as-synthesized samples were dried under a vacuum atmosphere at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.4. Characterization

Crystal structures of the synthesized MoS2/Ni2P samples were determined by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, SmartLab, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) from 5 to 100 angles at a scanning rate of 5°/min. The morphologies of the samples were obtained using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-4800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. The elemental compositions and chemical states of these three MoS2/Ni2P samples were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS, ESCALAB MK II, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using Mg Kα as the excitation source. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface areas of the obtained samples were examined by N2 adsorption/desorption measurement on a Nova 4000e analyzer (Quantachrome Instrument, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) at 77 K.

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

Before preparing the working electrode, a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) of 3 mm in diameter was firstly polished with 1000# water sandpaper and cleaned with ethanol and deionized water. Typically, 5 mg of catalyst (Ni2P, MoS2, MoS2/Ni2P hybrids, and the commercial 20 wt % Pt/C) and 30 µL Nafion solution (5 wt %) were dispersed in 1 mL solution consisting of 250 µL absolute ethanol and 750 µL deionized water, and followed by sonication for 1 h to form a homogeneous ink. Then, 5 µL of the dispersion solution was loaded onto the surface of the polished GCE and the electrode was dried at room temperature; herein, the excessive ethanol present in the slurry was removed as much as possible by extending the drying time. Prior to each electrochemical test, the electrolyte solution was degassed by bubbling pure nitrogen gas for 30 min to remove the dissolved oxygen.

All electrochemical tests were conducted in a typical three-electrode system attached to an electrochemical workstation (CHI 650C, Chenhua Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) in 1.0 mol/L KOH electrolyte. The GCE modified by the MoS2/Ni2P hybrids (MoS2, Ni2P or Pt/C) acted as the working electrode, while a Ag/AgCl electrode and a platinum foil were employed as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. The acquired potential values relevant to the Ag/AgCl electrode were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale: ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.059 pH + 0.209 V, i.e., the value of potential throughout this manuscript is relative to RHE. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was analyzed in the potential of −0.8 to 0.2 V at a scan rate of 2 mV/s. Tafel polarization curves were measured in a potential window of 0.3–0.65 V with a scan rate of 2 mV/s. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were conducted in a potential window from −0.6 to 0.8 V at a scan rate of 10 mV/s. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out at a cathodic overpotential of 0.7 V by employing the sinusoidal signal amplitude of 5 mV; the frequency ranged from 105 to 0.01 Hz.

2.6. Computational Details

The calculations based on DFT were implemented in the Materials Studio DMol3 (version 7.0, Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) [50,51]. Pulay’s direct inversion in the iterative subspace (DIIS) technique, as well as double numerical plus polarization functions (DNP) and the revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (RPBE) functional were employed. The effective core potential was applied to treat the core electrons of nickel atoms. With respect to the aqueous HER process, a continuum solvation model (COSMO) was used and water with the dielectric constant of 78.54 as the solvent [52]. In addition, for the purpose of taking into account of the weak interactions (hydrogen bond and van der Waals force), the TS (Tkatchenko-Scheffler) method for DFT-D correction was employed [52].

As is well known, the basal plane of MoS2 has been validated as chemically inert, thus, only the Mo edge-type structure of this catalyst was considered [30]. Three kinds of geometries for MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/Ni2P catalysts were employed: a (4 × 5 × 1) supercell with two S-Mo-S trilayer for MoS2, a (2 × 1 × 1) supercell derived from Ni2P (111) crystal surface with four layers, and a single (4 × 5 × 1)-sized trilayer MoS2 combined by three (2 × 1 × 1)-sized Ni2P layers for MoS2/Ni2P. A vacuum with the thickness of 15 Å in the z-direction was used to separate neighboring slabs and to minimize the interactions between them. During the calculations, only the first layers of MoS2 and Ni2P were relaxed in order to save time and computational cost.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Samples

3.1.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

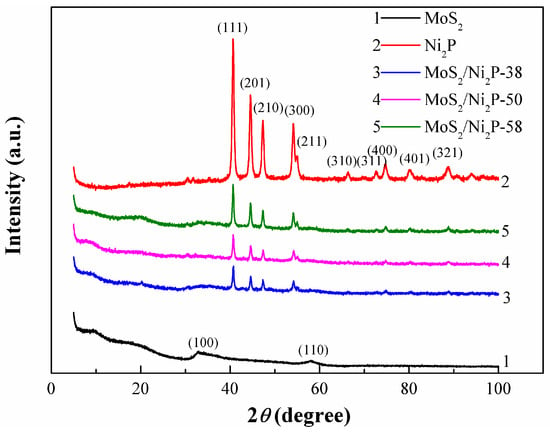

The XRD patterns of MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids (MoS2/Ni2P-38, MoS2/Ni2P-50, and MoS2/Ni2P-58) are displayed in Figure 1. The characteristics peaks at 2θ = 33.8° and 57.1° (curve 1) can be identified, corresponding to (100) and (110) crystal planes of MoS2, respectively. Herein, it should be noted that the diffraction peak of (002) plane of MoS2 is undetected. The absence of the (002) diffraction peak of MoS2 indicates a low stacking height along this direction [5,53]. As demonstrated in curve 2, the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 40.71°, 44.61°, 47.34°, 54.19°, 54.96°, 66.37°, 72.4°, 74.9°, 80.5°, and 88.6° corresponding to (111), (201), (210), (300), (211), (310), (311), (400), (401), and (321) confirm the presence of hexagonal Ni2P; besides the above-mentioned peaks, the detectable weak peaks (2θ = 30.36°, 31.58°) may be attributed to the coexistence of Ni5P4 phase [54], and another weak peak at 2θ = 35.4° can be assigned to the presence of Ni12P5 phase [55]. XRD patterns of the MoS2/Ni2P hybrids are presented in curves 3–5. The diffraction patterns of MoS2/Ni2P hybrids consist of very weak diffraction peak of MoS2, which indicates that the MoS2 is amorphous [5]. In addition, the diffraction peaks related to MoS2 and Ni2P are observed, thus suggesting the successful combination between MoS2 and Ni2P. It may be indexed to a proof of the fabrication of MoS2/Ni2P hybrid. Compared with pure Ni2P, the diffraction intensity of Ni2P crystal for three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids becomes weak. However, with the increase of Ni2P addition, intensities of diffraction peaks attributed to Ni2P become strong and those of MoS2 show a descending trend, which indicates that Ni2P plays a major role in the crystallinity of the hybrids.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids.

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

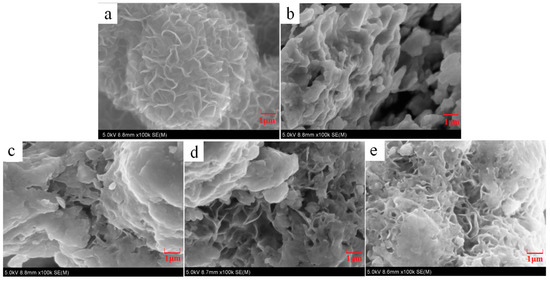

The morphologies of MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids are given in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2a, the nanoflower-like structure of MoS2 can be ascertained; of course, there are some nanosheets randomly stacking, which may lead to the decrease in active sites. The fabricated Ni2P particle exhibits a nanosheet-type morphology (Figure 2b), which would be advantageous to electrochemical conduction among the active sites. Morphologies of the three hybrids are observed in Figure 2c (MoS2/Ni2P-38), 2d (MoS2/Ni2P-50) and 2e (MoS2/Ni2P-58). All of them exhibit a mixed morphology of flower-like and lamellar structures.

Figure 2.

SEM images of MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids: (a) MoS2; (b) Ni2P; (c) MoS2/Ni2P-38; (d) MoS2/Ni2P-50; and (e) MoS2/Ni2P-58.

As for the SEM pictures of hybrids, with the increasing addition of Ni2P, the flower-shaped structure can be more easily observed, the presence of the Ni2P nanosheet will be helpful for the fabrication of MoS2 nanoflowers. For the sample of MoS2/Ni2P-38, the small amount of Ni2P cannot provide an abundant depositing area, thereby resulting in the serious agglomeration of MoS2 (Figure 2c). For MoS2/Ni2P-50 sample (the mass ratio of MoS2 and Ni2P is 1:1), it can be observed that the petal structure and the plate-type structure uniformly coexist (Figure 2d), and more well-proportioned nanoflower-like MoS2 particles distribute on the surface of Ni2P. Whereas, for MoS2/Ni2P-58 (Figure 2e), with the large addition of Ni2P, it is explicit that the dense MoS2 flower structure can be obtained, showing a resemblance to that of MoS2 (Figure 2a). By a comparison of morphologies of the three hybrids, for the MoS2/Ni2P-50 sample, the MoS2 nanoparticles evenly disperses on the surface of the Ni2P nanosheet.

3.1.3. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

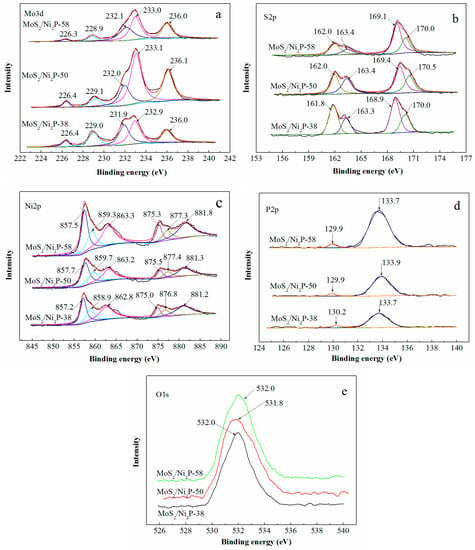

The elemental compositions and their valences of three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids were measured by XPS. The Mo 3d, S 2p, Ni 2p, P 2p and O 1s high-resolution spectra of three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids are respectively presented in Figure 3, and the corresponding bond energies and assignments are given in Table 1. As shown in Figure 3a, the characteristic peaks located at 229.0 eV and 231.9 eV (take MoS2/Ni2P-38 as an example, the following is the same) can be assigned to Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 respectively, suggesting the existence of Mo4+. The two peaks at 232.9 eV and 236.0 eV are ascribed to the compounds MoO3 or MoO42− (Mo6+) due to the oxidation of the samples. In addition, the weak peak appearing at 226.4 eV corresponds to S 2s of MoS2 [56]. For S 2p spectra, which is shown in Figure 3b, the two peaks at 161.8 eV and 163.3 eV are attributed to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals of divalent sulfide ion (S2−), while the other two peaks at 168.9 eV and 170.0 eV represent the existence of tetravalent sulfur in the form of SO32− (S4+). Generally, the sulphur atom with a +4 state locates at the edge of MoS2 layered structure due to the oxidation of MoS2 particle [57].

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids: (a) Mo 3d; (b) S 2p; (c) Ni 2p; (d) P 2p; and (e) O 1s.

Table 1.

Bond energies and assignments of Mo 3d, S 2p, Ni 2p, P 2p, and O 1s photoelectron peaks of three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids.

As shown in Figure 3c, the three peaks observed at 857.2 eV, 858.9 eV and 862.8 eV may be assigned to Niδ+ (0 < δ < 2) in Ni2P, oxidized Ni species (Ni2+) and the satellite of Ni 2p3/2, respectively, while the other three peaks at 875.0 eV, 876.8 eV, and 881.2 eV can be indexed to Niδ+ in Ni2P, oxidized Ni species, and the satellite of Ni 2p1/2 [58]. As for the P 2p spectra (Figure 3d), the peak at 130.2 eV is mark of metal-P bonds in metal phosphides, the peak at 133.7 eV can be assumed to the oxidized P species because the samples are exposed to the air [59].

Additionally, the O 1s peak (Figure 3e), with the binding energies of 532.0 eV, indicates the existence of Mo(IV)-O bond [60]. Thus, to some extent, it is also confirmed that the three hybrids were oxidized during the preparation process.

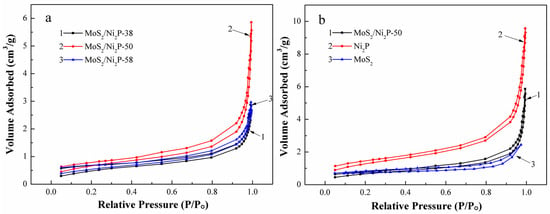

3.1.4. N2 Adsorption/Desorption Isotherm Measurement

The specific surface areas of the as-synthesized pure MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids were characterized by N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm measurement (Figure 4). All curves reveal a type IV isotherm with a distinct hysteresis loop, indicating the mesoporous structures of the above samples. The specific surface areas of aforementioned three hybrids are in a trend: MoS2/Ni2P-50 (2.42 m2/g) > MoS2/Ni2P-58 (1.95 m2/g) > MoS2/Ni2P-38 (1.86 m2/g). The specific surface areas of these three hybrids are smaller than that of pure Ni2P (4.62 m2/g). For pure MoS2, although its specific surface area (7.04 m2/g) is larger than the other four samples, its basal surface is HER inert, so it cannot provide abundant active sites for hydrogen adsorption, which means an inferior HER property. Among the three hybrids, MoS2/Ni2P-50 possess the largest specific surface area, the HER performance of this hybrid will be more outstanding than the other two hybrids. However, its HER characteristic cannot be comparable to that of Ni2P, because of its smaller determined specific surface area (ca. 52.4% of that of Ni2P).

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption/desorption curves of the samples: (a) MoS2/Ni2P-38, MoS2/Ni2P-50, and MoS2/Ni2P-58; (b) MoS2/Ni2P-50, Ni2P, and MoS2.

3.2. Electrochemical Analysis of HER

3.2.1. Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV)

The LSV curves of all samples in 1.0 mol/L KOH at a scan rate of 2 mV/s are depicted in Figure 5. The obtained onset overpotentials (ηonset) [61] are tabulated in Table 2. All samples were measured within the potential window of −0.8~0.2 V. The pure MoS2 shows the lower HER activity which is attributed to its inert basal surface and inferior conductivity [28]. By contrast, HER performances of the three hybrids are higher than pure MoS2 because of the excellent conductivity and affordable active sites. Although the catalytic performances of three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids are lower than those of Ni2P and commercial Pt/C, they can still raise attention in hydrogen evolution reaction. When the potential was kept at −0.1 V, the cathodic current density of HER for tested samples is in the following sequence: MoS2 (1.56 mA/cm2) < MoS2/Ni2P-38 (1.86 mA/cm2) < MoS2/Ni2P-58 (2.52 mA/cm2) < MoS2/Ni2P-50 (3.53 mA/cm2) < Ni2P (5.71 mA/cm2) < Pt/C (8.57 mA/cm2). Herein, it should be mentioned that although Ni2P shows a better HER feature than the produced three hybrids, its stability will be worse in an alkaline solution [14]. Among the three hybrids, MoS2/Ni2P-50 shows a high cathodic current density (70 mA/cm2 at −0.48 V), thus exhibiting the best HER performance. The HER performance of this hybrid might be due to the excellent conductivity, as well as the coexistence of nanosheet-type Ni2P crystal on the bottom and nanoflower-like MoS2 on the surface. Without doubt, the incorporation of Ni2P brings a great enhancement in HER performance of MoS2.

Figure 5.

LSV curves of the pure MoS2, Ni2P, three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids, and commercial 20 wt % Pt/C. Scan rate: 2 mV/s, potential window: −0.8~0.2 V (vs. RHE).

Table 2.

The obtained values of onset overpotentials (ηonset), Tafel slope (b), and charge transfer coefficient (α).

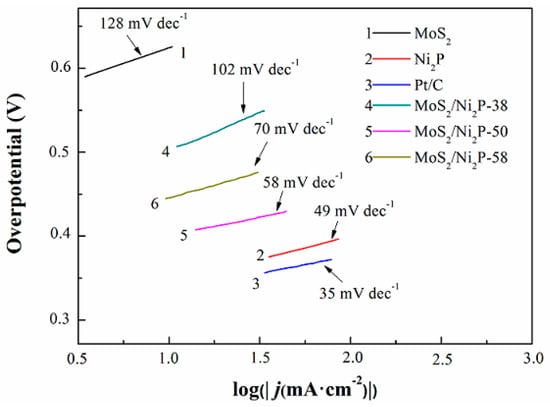

3.2.2. Tafel Polarization

Equation (1) was employed to describe the relationship of overpotential (η, V) and current density (j, mA/cm2); the charge transfer coefficient (α) can be obtained by Equation (2) [62]:

where b and R are the Tafel slope (mV/decade) and gas constant (8.314 J/(K∙mol)), respectively. A is an analyzed constant, T is the absolute temperature, me is number of electrons transferred, and F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol). According to published studies [12,13], the HER in alkaline solutions is typically considered as the Volmer-Heyrovsky process or Volmer-Tafel pathways, they are depicted as follows:

Volmer reaction: H2O + e → Hads +OH−;

Heyrovsky reaction: Hads + H2O + e → H2 + OH−;

Tafel reaction: Hads + Hads → H2

The kinetic mechanism in the HER process is determined by the rate-determining step (rds) of a multi-step reaction. The Tafel equation can play an important role in estimating the kinetic mechanism. The parameter of α corresponds to the rds for multi-step reactions, this is depicted as follows: the value of α is ~0.5 when the rds is Volmer reaction step, the value of α is ~1.5 when the rds is Heyrovsky reaction step, and the value of α will be close to 2 when the rds is step Tafel reaction [63,64]. Additionally, the Tafel slope is an important factor to describe the HER rate by examining the change of current density with overpotential. Generally, a small Tafel slope is desirable to drive a large catalytic current density at low overpotentials [65]. The Tafel plots of these samples derived from the polarization curves are shown in Figure 6. The HER performance of MoS2 is inferior due to its large Tafel slope (~128 mV/decade) and small α (0.46). Within three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids, MoS2/Ni2P-50 has a minimum Tafel slope (~58 mV/decade), indicative of the excellent HER performance. It might be a substitute to noble metals in HER application.

Figure 6.

Tafel plots of MoS2, Ni2P, three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids, and commercial 20 wt % Pt/C. Scan rate: 2 mV/s, potential window: 0.3~0.65 V.

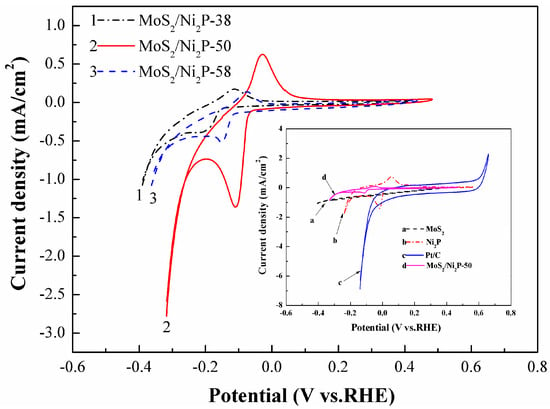

3.2.3. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurement (in a potential window of −0.6~0.8 V) can be helpful to reveal the reversibility of the electrochemical reaction. CV curves of MoS2/Ni2P-38, MoS2/Ni2P-50 and MoS2/Ni2P-58 samples are exhibited in Figure 7; the inset shows those of MoS2/Ni2P-50, pure MoS2, pure Ni2P and Pt/C. It can be seen from the determined CV curves that each of them is composed of an anodic oxidation and a cathodic reduction peak. The quasi-reversible redox peaks may be related to the processes of electrochemical hydrogen adsorption and electrochemical hydrogen desorption [28]. For the three hybrids, cathodic reduction potentials of them are as follows: −0.21 V for MoS2/Ni2P-38, −0.11 V for MoS2/Ni2P-50, and −0.15 V for MoS2/Ni2P-58. In addition, the current density follows the same tendency. Thus, a positive potential and the large current density for MoS2/Ni2P-50 composite can be validated, inferring its higher HER property than those of the other two hybrids.

Figure 7.

CV curves of pure MoS2, Ni2P, three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids and commercial 20 wt % Pt/C. Scan rate: 10 mV/s, potential window: −0.6~0.8 V (vs. RHE).

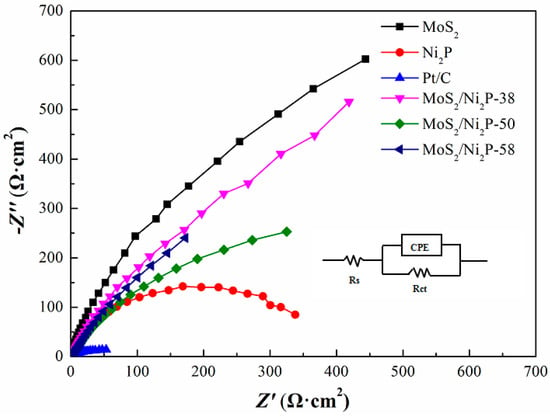

3.2.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

The obtained Nyquist plots for the pure MoS2, Ni2P and three MoS2/Ni2P samples are shown in Figure 8. The Rs (CPERct) equivalent circuit was adopted to analyze the obtained EIS data by use of Zsimpwin software. Where Rs (Ω·cm2) and Rct (kΩ·cm2) are the solution resistance and charge transfer resistance. The double layer capacitance (Cdl) and the exchange current density (j0) of the electrode are calculated by Equations (6) and (7) [6,66,67]:

Figure 8.

EIS spectra of pure MoS2, Ni2P, three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids, and commercial 20 wt % Pt/C. Cathodic overpotential: 0.7 V, frequency: 105 Hz–0.01 Hz, amplitude of the sinusoidal signal: 5 mV.

Herein, Q is the capacitance coefficient (Ω−1·sn·cm−2) of constant phase element (CPE), and n is the phase angle of constant phase element. R is the gas constant (J/(K·mol)), T is the absolute temperature (K), me is the number of switched electrons (the parameter of me is the same as that in Equation (2)) and F is the Faraday constant. The calculated values of them are also reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), double-layer capacitance (Cdl), the dimensionless CPE exponent n, and exchange current density (j0) analyzed from the EIS spectra.

Of all the tested samples, it is no doubt that Pt/C, with the feature of the largest Cdl and j0, exhibits the best HER performance. Apart from the commercial Pt/C specimen, among other five lab-made samples, pure Ni2P has the largest Cdl and j0, followed by the three hybrids and, lastly, by the pure MoS2. From the above results, it seems that Ni2P is an ideal HER catalyst, however, the demerit of its instability in alkaline solution will retard its application. Although Cdl and j0 of the three hybrids are smaller than Ni2P, they are much larger than that of MoS2. Among these catalysts, the HER performance of MoS2/Ni2P-50 is remarkable.

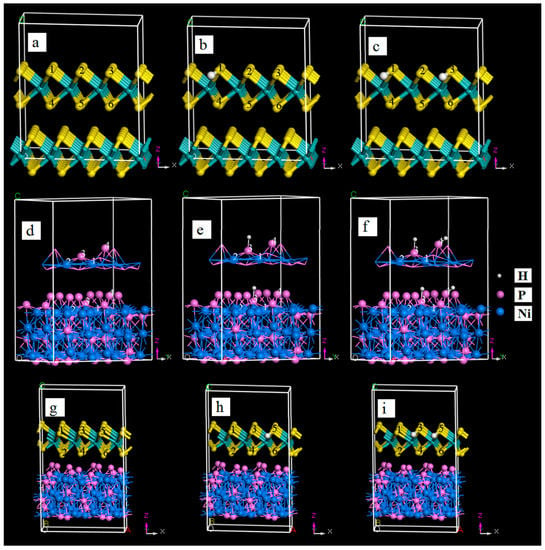

3.3. DFT Calculations

The optimized structures of the three catalysts of MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/Ni2P without hydrogen adsorption, as well as those with one and two adsorbed hydrogen atoms are shown in Figure 9. The adsorption energy (ΔEads) and Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔGads) for the uptake of hydrogen by the catalyst at 298 K were calculated using Equations (8) and (9) [30].

where E(catalyst + xH, x = 1 or 2) is the COSMO-corrected total energy for the system containing the catalyst support and x adsorbed hydrogen atoms, E(catalyst + (x − 1)H) is that of for (x − 1) adsorbed hydrogen atoms-including system, and E(H2) is the energy of an isolated hydrogen molecule. G(X) is the computed temperature-corrected free energy of the aforesaid species (X) at 298 K. ΔEads shows the absorption capability catalyst toward the hydrogen atom; the more negative value of ΔEads suggests the stronger interaction between them, and the geometry with the most negative ΔEads will be more stable. The negative value of ΔGads convinces the spontaneous characteristic of the adsorption interaction process.

Figure 9.

The optimized structures of MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/Ni2P three catalysts without hydrogen adsorption, as well as those with one and two adsorbed hydrogen atoms. (a) MoS2; (b) MoS2-1H; (c) MoS2-2H; (d) Ni2P; (e) Ni2P-1H; (f) Ni2P-2H; (g) MoS2/Ni2P; (h) MoS2/Ni2P-1H; and (i) MoS2/Ni2P-2H.

As for pristine MoS2, there are six edge sites (identified by numbers in Figure 9a) that can absorb the hydrogen atom. After one hydrogen atom capture, ΔEads(MoS2 + H) values are as follows: −16.12 kcal/mol for site 1, −16.07 for site 2, −16.08 for site 3, −12.91 for site 4, −12.98 for site 5, and −12.97 kcal/mol for site 6. Therefore, among these six sites, site 1 is more suitable than others for the anchor of hydrogen atom (Figure 9b). When one hydrogen atom is absorbed, the negative ΔGads of all six hydrogen-containing configurations (−13.47, −13.34, −13.35, −9.55, −9.67, and −9.61 kcal/mol for hydrogen atom at sites 1–6) indicates the spontaneous characteristic of the hydrogen uptake. After one hydrogen atom adsorption, there are only five edge sites (2–6) for trapping another hydrogen atom. Among geometries for the two hydrogen atoms, the structure with ΔEads of −14.78 kcal/mol for MoS2 with sites 1 and 3 for the capture of hydrogen atoms (Figure 9c) is most stable; ΔEads for others are: −13.52 kcal/mol for sites 1 and 2, −2.45 kcal/mol for sites 1 and 4, −12.37 kcal/mol for sites 1 and 5, and −13.19 kcal/mol for sites 1 and 6. The values of ΔGads of these five compounds are negative, also inferring the easy uptake of the second hydrogen atom. Of course, by comparison of ΔEads, the capture of the first hydrogen atom is easier than that of the second one.

For the case of hydrogen adsorption by Ni2P, all four sites (labeled by numbers in Figure 9d) are employed to trap hydrogen atoms. Site 3 is desirable for the capture of the first hydrogen atom (Figure 9e), and the value ΔEads for the hydrogen-capturing compound is −6.095 kcal/mol; those for the other three compounds are −1.658 kcal/mol at site 1, −4.889 kcal/mol at site 2, and −4.898 kcal/mol at site 4. Values of ΔGads for hydrogen trapper at sites 1–4 are −0.235 kcal/mol, −4.037 kcal/mol, −4.045 kcal/mol and −4.036 kcal/mol, respectively. As for the three systems containing two hydrogens, ΔEads and ΔGads of them are −0.31 and 1.74 kcal/mol for sites 3 and 1, 1.78 and 0.33 kcal/mol for sites 3 and 2, and −4.19 and −2.23 kcal/mol for sites 3 and 4. Therefore, the Ni2P catalyst tends to use sites 3 and 4 to trap hydrogen atoms (Figure 9f).

Lastly, for the hydrogen capture by the MoS2/Ni2P hybrid, among the six edge sites of top MoS2 layer (Figure 9g), which is dissimilar to that of the pure MoS2, site 5 is more competent for trapping the first hydrogen atom (Figure 9h), in view of ΔEads and ΔGads as follows: −4.79 and −3.57 kcal/mol for site 1, 9.15 and 11.25 kcal/mol for site 2, −4.89 and −4.83 kcal/mol for site 3, −4.99 and −4.64 kcal/mol for site 4, −6.78 and −8.36 kcal/mol for site 5, and −5.2 and −6.87 kcal/mol for site 6. Additionally, for the adsorption of two hydrogen atoms, sites 5 and 3 (Figure 9i) are the most acceptable, because of the following values of ΔEads and ΔGads for the second hydrogen uptake: −3.81 and −1.88 kcal/mol for site 1, −3.56 and −1.77 kcal/mol for site 2, −6.30 and −2.73 kcal/mol for site 3, −6.29 and −2.58 kcal/mol for site 4, 7.32 and 11.90 kcal/mol for site 6. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that for S atoms at the sites 4 and 6, the distances between which and the second hydrogen atom are extended, and this hydrogen atom tends to close to the S atoms at sites 3 and 5.

In terms of the DFT calculations results, for the first and second hydrogen uptakes, ΔEads and ΔGads of MoS2 are the most negative, followed by MoS2/Ni2P and Ni2P. Compared with that of MoS2, affinities of MoS2/Ni2P and Ni2P to hydrogen neither too strong nor too weak, indicating its excellent HER performance [51,68]. In addition, the ΔGads of Ni2P that capturing hydrogen atoms is more close to zero than those of the other two systems, it is sure that the HER property of Ni2P is higher than those of MoS2 and MoS2/Ni2P hybrids [51,69]. Thus, it can be concluded that the HER performances for these catalysts are in an order of Ni2P > MoS2/Ni2P > MoS2. This deduction is consistent with the experimental tests. Herein, the combination between MoS2 and Ni2P, and the role of Ni2P in the enhancement of MoS2 HER property will be investigated in a further study.

3.4. HER Stability of the MoS2/Ni2P Hybrids

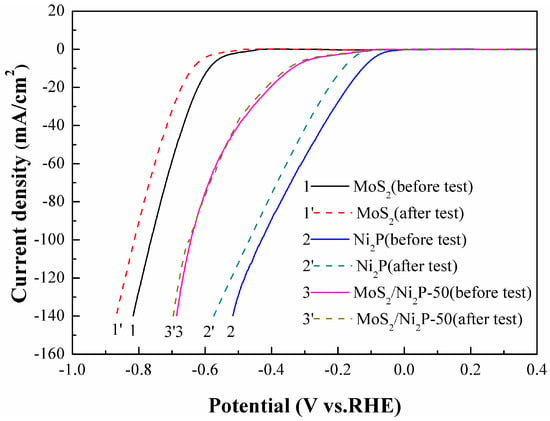

For practical applications, in addition to the HER activity mentioned above, the stability of electrocatalysts is another important criterion to evaluate the catalytic activity. To assess the durability of pure MoS2, Ni2P, and the MoS2/Ni2P-50 hybrid, continuous CV tests for 1000 cycles with the potential in range of −1.0 to 0.4 V were conducted at a scan rate of 50 mV/s in 1.0 mol/L KOH (Figure 10). By comparison of polarization curves of these three samples before and after 1000 cycles, the cathodic current densities of them decrease somewhat after tests. Compared with electrocatalytic behaviors of pure MoS2 and Ni2P, the MoS2/Ni2P-50 hybrid just shows a slight decay, and thereby exhibits an excellent durability in the HER process.

Figure 10.

Stability tests for the pure MoS2, Ni2P, and MoS2/Ni2P-50 hybrid. Scan rate: 50 mV/s, potential window: −1.0 to 0.4 V (vs. RHE).

4. Conclusions

In this work, morphologies, crystallinities, and chemical components of pure MoS2, Ni2P, and three MoS2/Ni2P hybrids obtained via a hydrothermal synthesis process were characterized. Then, HER performances of them in 1.0 mol/L KOH solution were evaluated. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The result of DFT calculation is in consistence with that of experimental test. The incorporated Ni2P observably enhances the HER property of MoS2. Among the three fabricated kinds of catalysts, the HER performance of them follows the trend: Ni2P > MoS2/Ni2P > MoS2.

- (2)

- The MoS2/Ni2P-50 shows a large cathodic current density (70 mA/cm2 at −0.48 V) and small Tafel slope (~58 mV/decade), thus exhibiting the higher HER activity than other two MoS2/Ni2P hybrids.

- (3)

- The excellent HER performance of MoS2/Ni2P-50 hybrid can be due to the desirable conductivity, the uniform morphology, large specific surface area, and favorable stability.

Author Contributions

F.Y. and N.K. prepared the manuscript. L.S. designed this work and gave the guidance for HER evaluation. F.Y., J.Y., N.K., and S.H. performed the experiments and the measurement of HER. J.H., X.W., and F.Y. analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hebei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number B2016203012), and the Science and Technology Support Key Research and Development Program of Qinhuangdao, China (grant number 201703A012).

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely thankful to the editors and the reviewers for giving valuable and instructive comments for the revision of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, L.; Yu, T.W.; Lei, W.; Liu, W.W.; Feng, K.; Ding, Y.L.; Jiang, G.P.; Xu, P.; Chen, Z.W. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanocones encapsulating with nickel–cobalt mixed phosphides for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 16568–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, P.W.; Ci, S.Q.; Wen, Z.H. Strongly coupled 3D nanohybrids with Ni2P/carbon nanosheets as pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction electrocatalysts. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.M.; Xia, Z.M.; Gao, W.; Qu, Y.Q. Highly efficient and robust nickel phosphides as bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water-splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10826–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.Z.; Wang, X.L.; Wen, F.S.; Niu, L.J.; Shi, X.M.; Yan, J.Y. Hydrogen evolution reaction performance of the molybdenum disulfide/nickel–phosphorus composites in alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 18942–18952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.; Pan, Z.; Wu, Z.Z.; Wang, Z.P.; Liu, Z.H. Hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2 nanoflowers as highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts. J. Power Sources 2014, 264, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Li, Y.; Yin, X.C.; Wang, Y.Z.; Lu, L.; Song, A.L.; Xia, M.R.; Li, Z.P.; Qin, X.J.; Shao, G.J. Comparison of three nickel-based carbon composite catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 22655–22662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.X.; Song, X.H.; Wang, Y.R.; Chen, X. Electrodeposition-assisted synthesis of Ni2P nanosheets on 3D graphene/Ni foam electrode and its performance for electrocatalytic hydrogen production. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Guio, C.G.; Stern, L.A.; Hu, X. Nanostructured hydrotreating catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6555–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merki, D.; Hu, X. Recent developments of molybdenum and tungsten sulfides as hydrogen evolution catalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3878–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Yousaf, A.B.; Chen, M.M.; Wei, C.S.; Wu, X.; Huang, N.D.; Qi, Z.M.; Li, L.B. Molybdenum sulfide/graphene-carbon nanotube nanocomposite material for electrocatalytic applications in hydrogen evolution reactions. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.Y.; Zhang, L.S.; Luo, L.; Lu, J.J.; Yin, S.B.; Shen, P.K.; Tsiakaras, P. N-doped porous molybdenum carbide nanobelts as efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 224, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.C.; Sun, G.; Song, A.L.; Wang, L.X.; Wang, Y.Z.; Dong, H.F.; Shao, G.J. A novel structure of Ni–(MoS2/GO) composite coatings deposited on Ni foam under supergravity field as efficient hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts in alkaline solution. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 249, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.C.; Sun, G.; Wang, L.X.; Bai, L.; Su, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Du, Q.H.; Shao, G.J. 3D hierarchical network NiCo2S4 nanoflakes grown on Ni foam as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for both hydrogen and oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 25267–25276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popczun, E.J.; McKone, J.R.; Read, C.G.; Biacchi, A.J.; Wiltrout, A.M.; Lewis, N.S.; Schaak, R.E. Nanostructured nickel phosphide as an electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9267–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.G.; Vrubel, H.; Bensimon, M.; Hu, X. Easily-prepared dinickel phosphide (Ni2P) nanoparticles as an efficient and robust electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 5917–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.R.; Hu, W.H.; Li, X.; Dong, B.; Shang, X.; Han, G.Q.; Chai, Y.M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.G. One-pot synthesis of hierarchical Ni2P/MoS2 hybrid electrocatalysts with enhanced activity for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 383, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yang, N.; Chen, Y.J.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.P.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.G. Nickel phosphide nanoparticles-nitrogen-doped graphene hybrid as an efficient catalyst for enhanced hydrogen evolution activity. J. Power Sources 2015, 297, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.J.; Evans, P.; Zangari, G. Electrocatalytic properties of Ni-based alloys toward hydrogen evolution reaction in acid media. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, A551–A557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.G.; Li, L.L.; Han, X.P.; Sun, W.P.; Srinivasan, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.G.; Cheng, F.Y.; Yan, Q.Y.; Chen, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Cobalt sulfide nanosheet/graphene/carbon nanotube nanocomposites as flexible electrodes for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. 2014, 53, 12594–12599. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.X.; Yang, B.; Wu, X.L.; Li, Z.J.; Lei, L.C.; Zhang, X.W. Polymorphic CoSe2 with mixed orthorhombic and cubic phases for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.H.; Liu, P.F.; Pan, L.F.; Wang, H.F.; Yang, Z.Z.; Zheng, L.R.; Hu, P.; Zhao, H.J.; Gu, L.; Yang, H.G. Local atomic structure modulations activate metal oxide as electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution in acidic water. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.F.; Wang, C.H.; Sasaki, K.; Marinkovic, N.; Xu, W.; Muckerman, J.T.; Zhu, Y.; Adzic, R.R. Highly active and durable nanostructured molybdenum carbide electrocatalysts for hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.F.; Sasaki, K.; Ma, C.; Frenkel, A.I.; Marinkovic, N.; Muckerman, J.T.; Zhu, Y.M.; Adzic, R.R. Hydrogen-evolution catalysts based on non-noble metal nickel–molybdenum nitride nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6131–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.F.; Gu, S.; Liu, R.W.; Li, C.M. Highly active and inexpensive iron phosphide nanorods electrocatalyst towards hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 14272–14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibsgaard, J.; Chen, Z.B.; Reinecke, B.N.; Jaramillo, T.F. Engineering the surface structure of MoS2 to preferentially expose active edge sites for electrocatalysis. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merki, D.; Fierro, S.; Vrubel, H.; Hu, X.L. Amorphous molybdenum sulfide films as catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen production in water. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.R.; Hu, W.H.; Li, X.; Dong, B.; Shang, X.; Han, G.Q.; Chai, Y.M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.G. Facile one-pot synthesis of CoS2–MoS2/CNTs as efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 384, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Song, L.Z.; Yan, J.Y.; Kang, N.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, W. Hydrogen evolution reaction property in alkaline solution of molybdenum disulfide modified by surface anchor of Nickel—Phosphorus coating. Metals 2017, 7, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, X.J.; Zhu, J.; Liao, L.; Scanlon, M.D.; Ge, P.Y.; Ji, C.; Girault, H.H.; Liu, B.H. Nanocomposite of MoS2 on ordered mesoporous carbon Nanospheres: A highly active catalyst for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 22, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Nørskov, J.K. Tuning the MoS2 edge-site activity for hydrogen evolution via support interactions. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Ortiz-Quiles, E.O.; Cabrera, C.R.; Chen, Z.F.; Zhou, Z. Layer-by-layer hybrids of MoS2 and reduced graphene oxide for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 147, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.F.; Huang, S.Y.; Li, Y.P.; Steinmann, S.N.; Yang, W.T.; Cao, L.Y. Layer-dependent electrocatalysis of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Sawyer, W.G.; Perry, S.S.; Sinnott, S.B.; Phillpot, S.R. Energetics of oxidation in MoS2 nanoparticles by density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 10606–10616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Z.; Fang, B.Z.; Wang, Z.P.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Liu, F.Y.; Wang, W.; Alfantazi, A.; Wang, D.Z.; Wilkinson, D.P. MoS2 nanosheets: A designed structure with high active site density for the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.T.; Lu, Z.Y.; Kong, D.S.; Sun, J.; Hymel, T.M.; Cui, Y. Electrochemical tuning of MoS2 nanoparticles on three-dimensional substrate for efficient hydrogen evolution. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 4940–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Li, H.B.; Xiao, J.P.; Tu, Y.C.; Deng, D.H.; Yang, H.X.; Tian, H.F.; Li, J.Q.; Ren, P.J.; Bao, X.H. Triggering the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity of inert two-dimensional MoS2 surface via single-atom metal doping. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, Z.Y.; Bao, S.Y.; Wang, M.F.; Qi, X.Y.; Fan, Z.X.; Zhang, H. Solution-phase epitaxial growth of noble metal nanostructures on dispersible single-layer molybdenum disulfide nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.H.; Han, G.Q.; Liu, Y.R.; Dong, B.; Chai, Y.M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.G. Ultrathin MoS2-coated carbon nanospheres as highly efficient electrocatalyts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 6552–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.B.; Cummins, D.; Reinecke, B.N.; Clark, E.; Sunkara, M.K.; Jaramillo, T.F. Core-shell MoO3–MoS2 nanowires for hydrogen evolution: A functional design for electrocatalytic materials. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4168–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Huo, J.; Yang, Y.D.; Xu, L.; Wang, S.Y. The Co3O4 nanosheet array as support for MoS2 as highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Energy Chem. 2017, 26, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Wang, H.L.; Xie, L.M.; Liang, Y.Y.; Hong, G.S.; Dai, H.J. MoS2 nanoparticles grown on Graphene: An advanced catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7296–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.D.; Yu, S.; Wu, S.Q.; Wen, Y.H.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, Z.Z. Structural and electronic properties of superlattice composed of graphene and monolayer MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 15347–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Zhao, L.; Liu, A.P.; Li, X.Y.; Wu, H.P.; Lu, C.D. Three-dimensional MoS2/rGO hydrogel with extremely high double-layer capacitance as active catalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 182, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, I. Hydrogen evolution reaction on Ni–P alloys: The internal stress and the activities of electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 4537–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gu, S.; Li, C.M. Electrodeposition of Nickel—Phosphorus nanoparticles film as a Janus electrocatalyst for electro-splitting of water. J. Power Sources 2015, 299, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaraju, J.N.; Jahan, S.M.; Jain, A.; Rajama, K.S. Structure and phase transformation behavior of electroless Ni–P alloys containing tin and tungsten. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 436, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.H.; Liu, Q.; Tang, C.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X.P. Ni2P nanoparticle films supported on a Ti plate as an efficient hydrogen evolution cathode. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 11031–11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raybaud, P.; Hafner, J.; Kresse, G.; Kasztelan, S.; Toulhoat, H. Ab initio study of the H2–H2S/MoS2 gas-solid Interface: The nature of the catalytically active sites. J. Catal. 2000, 189, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.P.; Yang, Z.X.; Ni, X.; Wu, N.N.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, X. Hydrogenation-induced edge magnetization in armchair MoS2 nanoribbon and electric field effects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 071901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.S.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, E.G.; Chung, Y.H.; Yoo, S.J.; Lee, Y.K. The nature of active sites of Ni2P electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Catal. 2015, 326, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Rodriguez, J.A. Catalysts for hydrogen evolution from the [NiFe] hydrogenase to the Ni2P (001) surface: The importance of ensemble effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14871–14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Song, L.Z.; Yang, F.F.; He, J. Investigation of phosphate adsorption by a polyethersulfone-type affinity membrane using experimental and DFT methods. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 25036–25056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, L.; Chen, W.X.; Wang, J.M. Synthesis of MoS2/C nanocomposites by hydrothermal route used as Li-ion intercalation electrode materials. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Senevirathne, K.; Aquilina, L.; Brock, S.L. Effect of synthetic levers on nickel phosphide nanoparticle formation: Ni5P4 and NiP2. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 7968–7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.B.; Dai, J.H. A simple mild hydrothermal route for the synthesis of nickel phosphide powders. Ceram. Int. 2010, 36, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Skeldon, P.; Thompson, G.E. XPS studies of MoS2 formation from ammonium tetrathiomolybdate solutions. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1997, 91, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, T.R.; Zhai, J. Layered MoS2 nanoparticles on TiO2 nanotubes by photocatalytic strategy as high-performance electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2764–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroteev, V.O.; Bulusheva, L.G.; Asanov, I.P.; Shlyakhova, E.V.; Vyalikh, D.V.; Okotrub, A.V. Charge transfer in the MoS2/carbon nanotube composite. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 21199–21204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Chen, Z.B.; Chen, Z.Z.; Lv, C.C.; Meng, H.; Zhang, C. Ni12P5 nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for hydrogen generation via electrolysis and photoelectrolysis. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8121–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, W.H.; Liu, D.P.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.G. Carbon nanotubes decorated with nickel phosphide nanoparticles as efficient nanohybrid electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 13087–13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Jin, S.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, M.H. Design of nickel electrodes by Electrodeposition: Effect of internal stress on hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 252, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Li, Y.G. Recent advances in heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 14942–14962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalbino, F.; Delsante, S.; Borzone, G.; Angelini, E. Electrocatalytic behaviour of Co–Ni–R (R = Rare earth metal) crystalline alloys as electrode materials for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline medium. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 6696–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.T.; Mathe, M. Hydrogen evolution reaction on single crystal WO3/C nanoparticles supported on carbon in acid and alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.S.; Cha, J.J.; Wang, H.T.; Lee, H.R.; Cui, Y. First-row transition metal dichalcogenide catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3553–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, G.J.; Van Den Eeden, A.L.G.; Sluyters-Rehbach, M.; Sluyters, J.H. The analysis of electrode impedances complicated by the presence of a constant phase element. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1984, 176, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunhiraman, A.K.; Ramasamy, M.; Ramanathan, S. Efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis triggered by electrochemically anchored platinum nano-islands on functionalized-MWCNT. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 9881–9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.D.; Yan, A.Z.; Feng, Y.C.; Li, L.; Sun, C.X.; Shao, Z.G.; Shen, P.K. Study of hydrogen evolution reaction on Ni–P amorphous alloy in the light of experimental and quantum chemistry. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 2709–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnemann, B.; Moses, P.G.; Bonde, J.; Jørgensen, K.P.; Nielsen, J.H.; Horch, S.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K. Biomimetic hydrogen evolution: MoS2 nanoparticles as catalyst for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5308–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).