Numerical Simulation of Arc Characteristics of VP-CMT Aluminum Alloy Arc Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

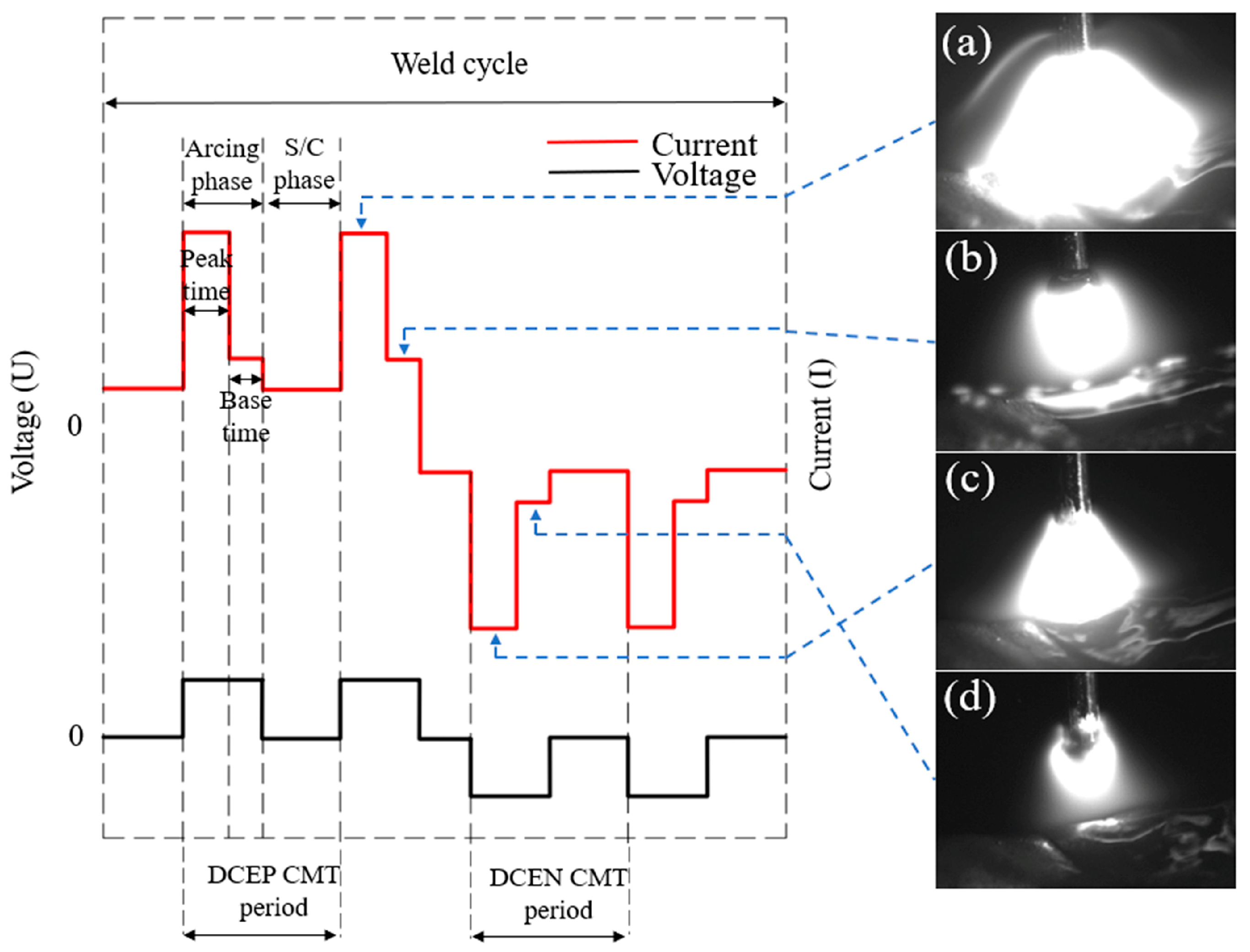

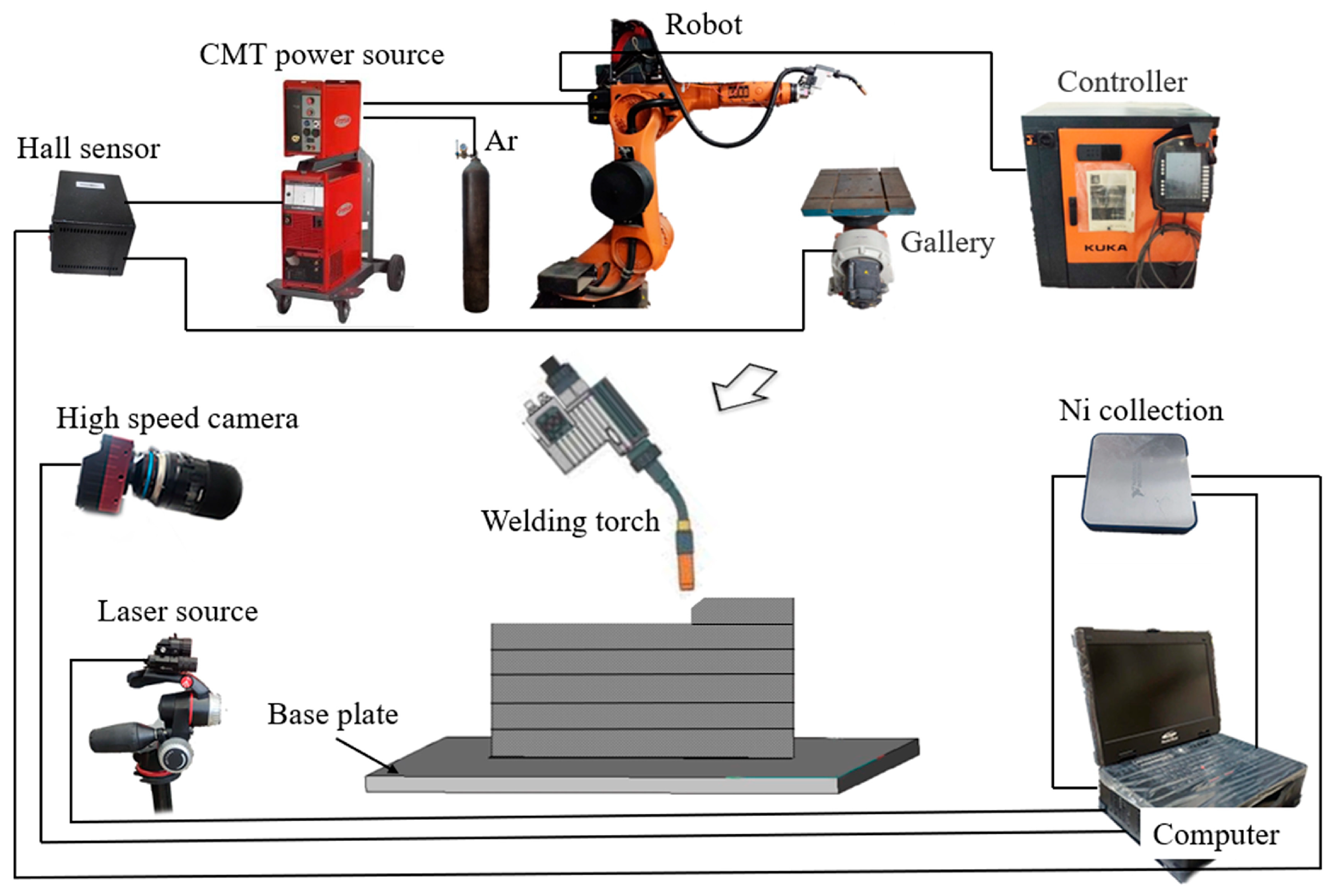

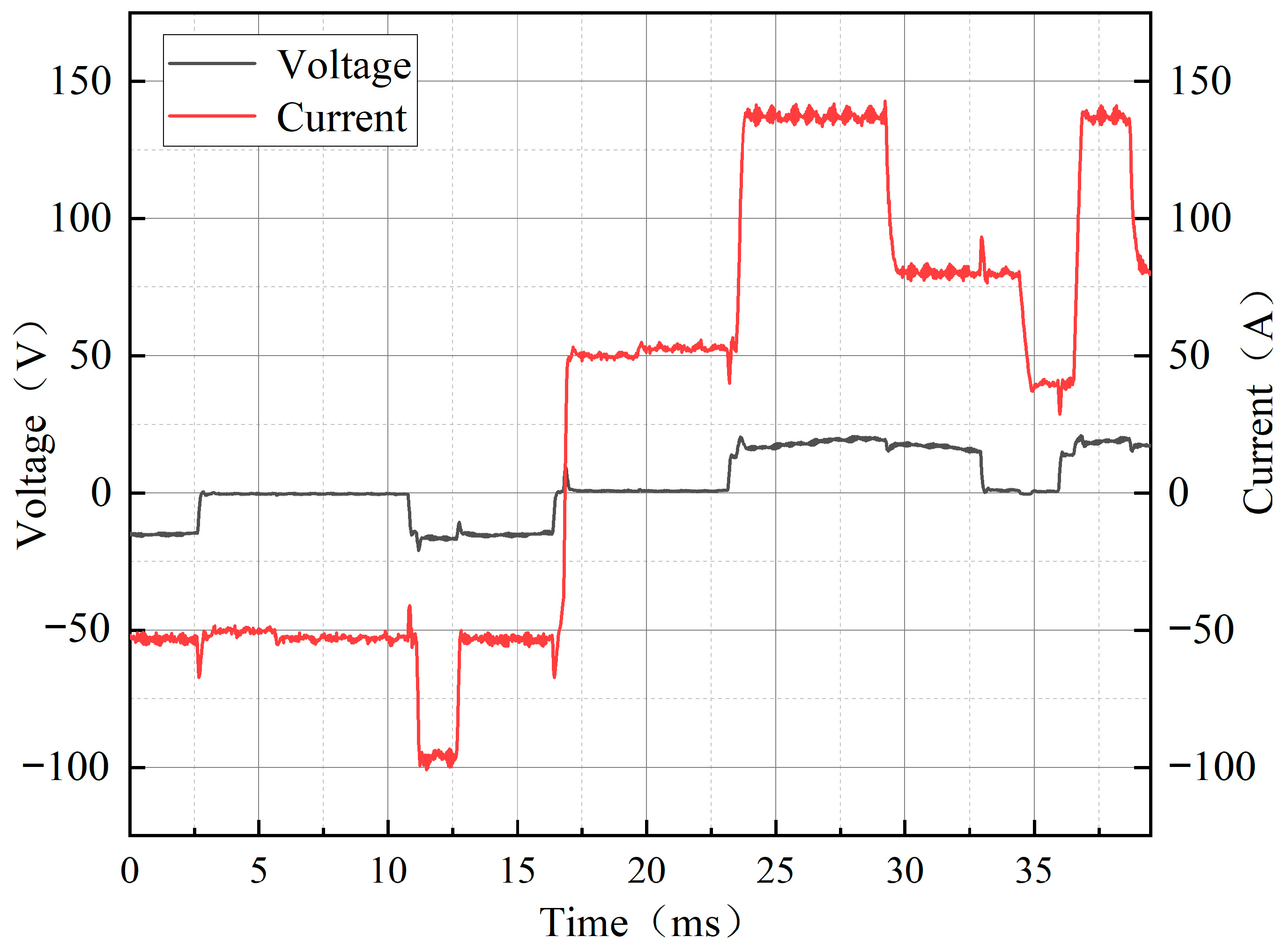

2. Additive Processes and Modeling of Arc Plasma Heat Transfer

2.1. Experimental Materials and Additive Processes

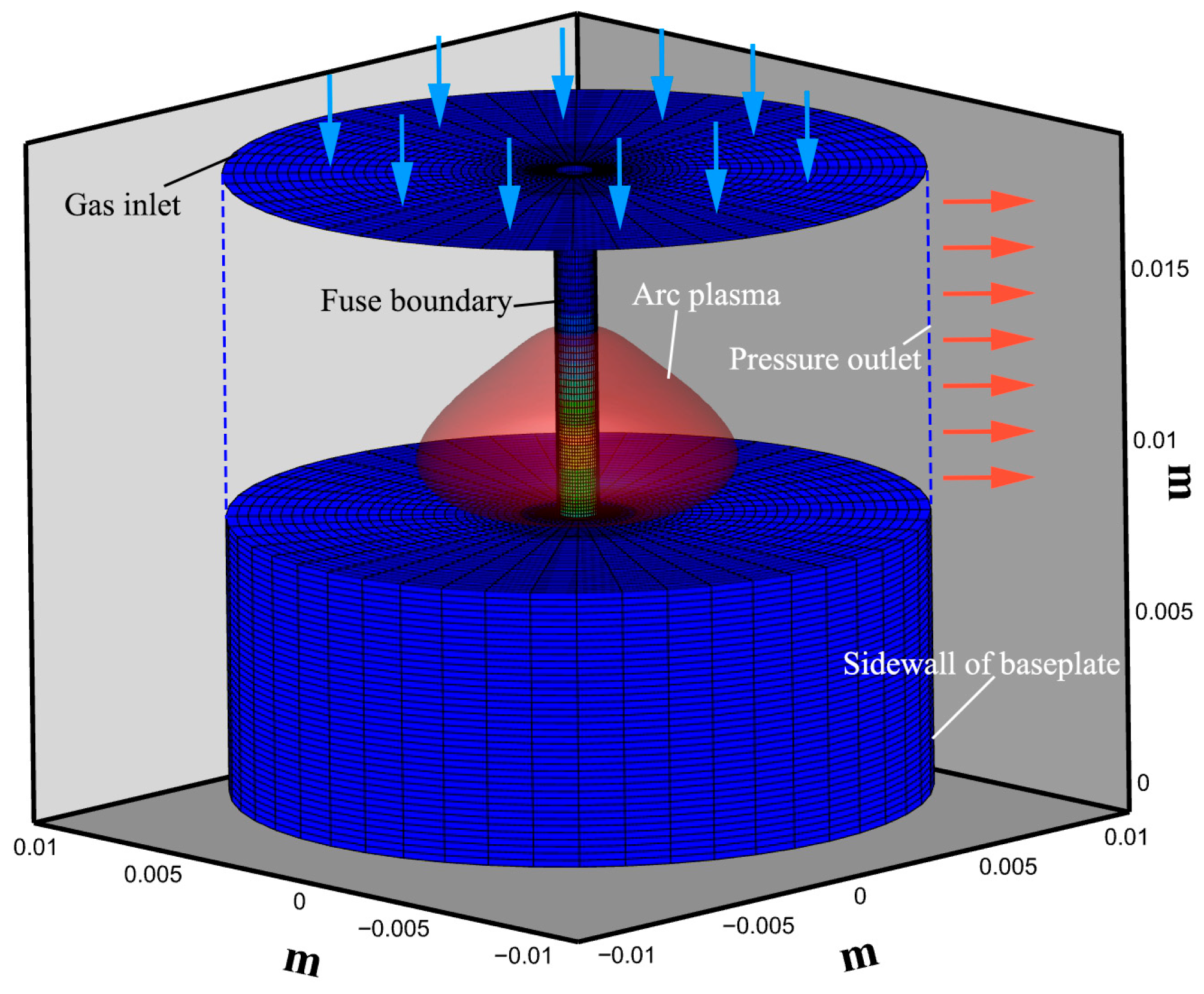

2.2. Modeling of Arc Plasma Heat Transfer Underlying Assumption

- (1)

- Arc plasma serves as the continuous, laminar Newtonian fluid under atmospheric pressure.

- (2)

- Arc plasma reaches the local thermodynamic equilibrium, i.e., it is characterized by the same particle temperature without considering the variability of the electron and heavy ion temperatures.

- (3)

- The arc plasma satisfies the optical thinness property.

- (4)

- The variation in multiphysics field within the welding wire and metal mass transfer process are neglected.

- (5)

- The melt pool is a laminar, unsteady, incompressible fluid.

- (6)

- The melt pool is treated with enthalpy–porosity for the mushy zone, and a Boussinesq approximate solution is applied for the buoyancy effect in the melt pool.

- (7)

- There is no free deformation of the surface of the melt pool, and mass and heat losses due to evaporation of the metal are not taken into account.

2.3. Governing Equations (Math.)

2.4. Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

3.1. Arc Isolation

Mechanism of Temperature Distribution in Heat Transfer Process of a Substrate

3.2. Electromagnetic Field Evolution Laws for Arc Plasma Heat Transfer Processes

3.3. Comparison of Experimental and Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

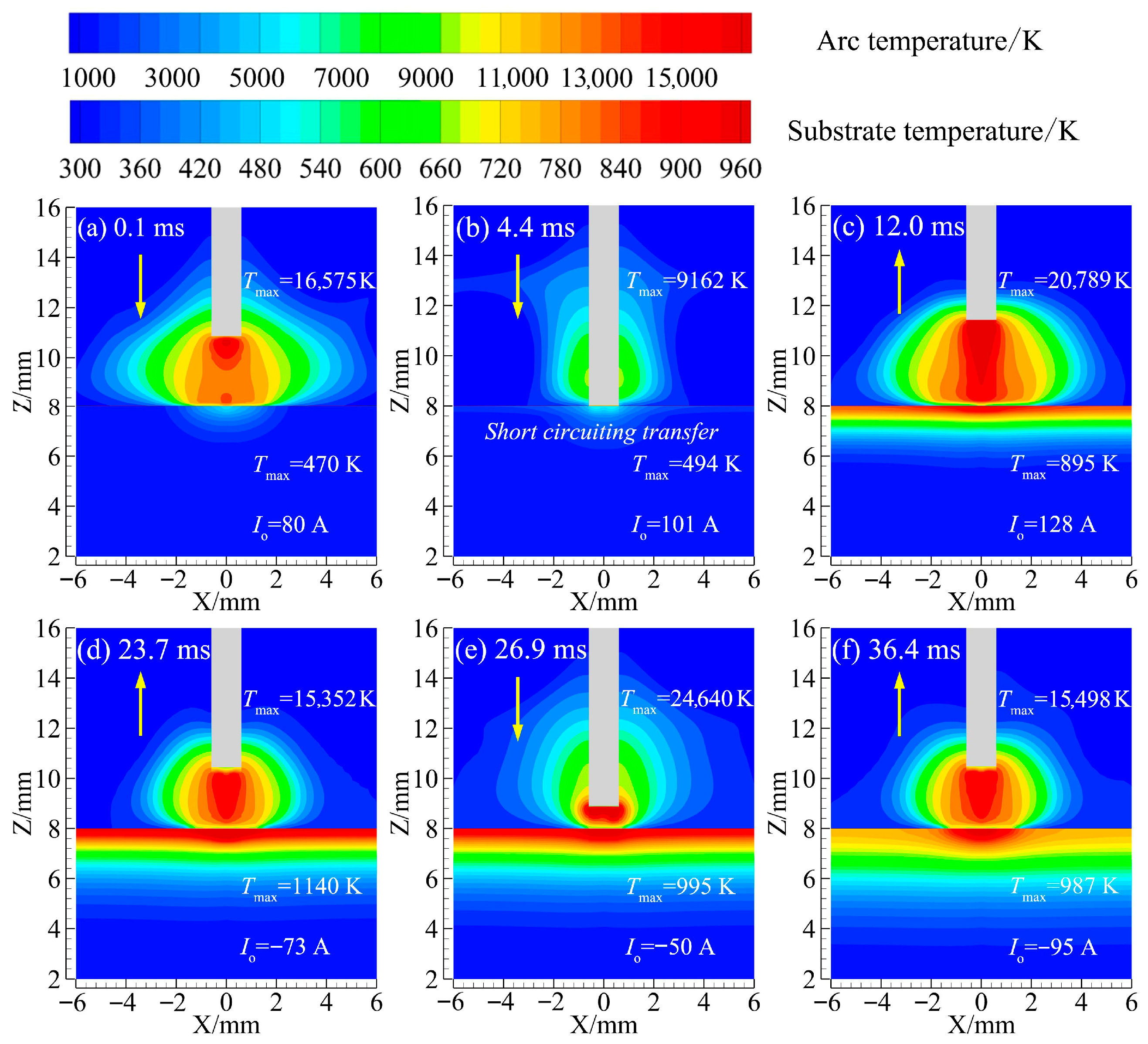

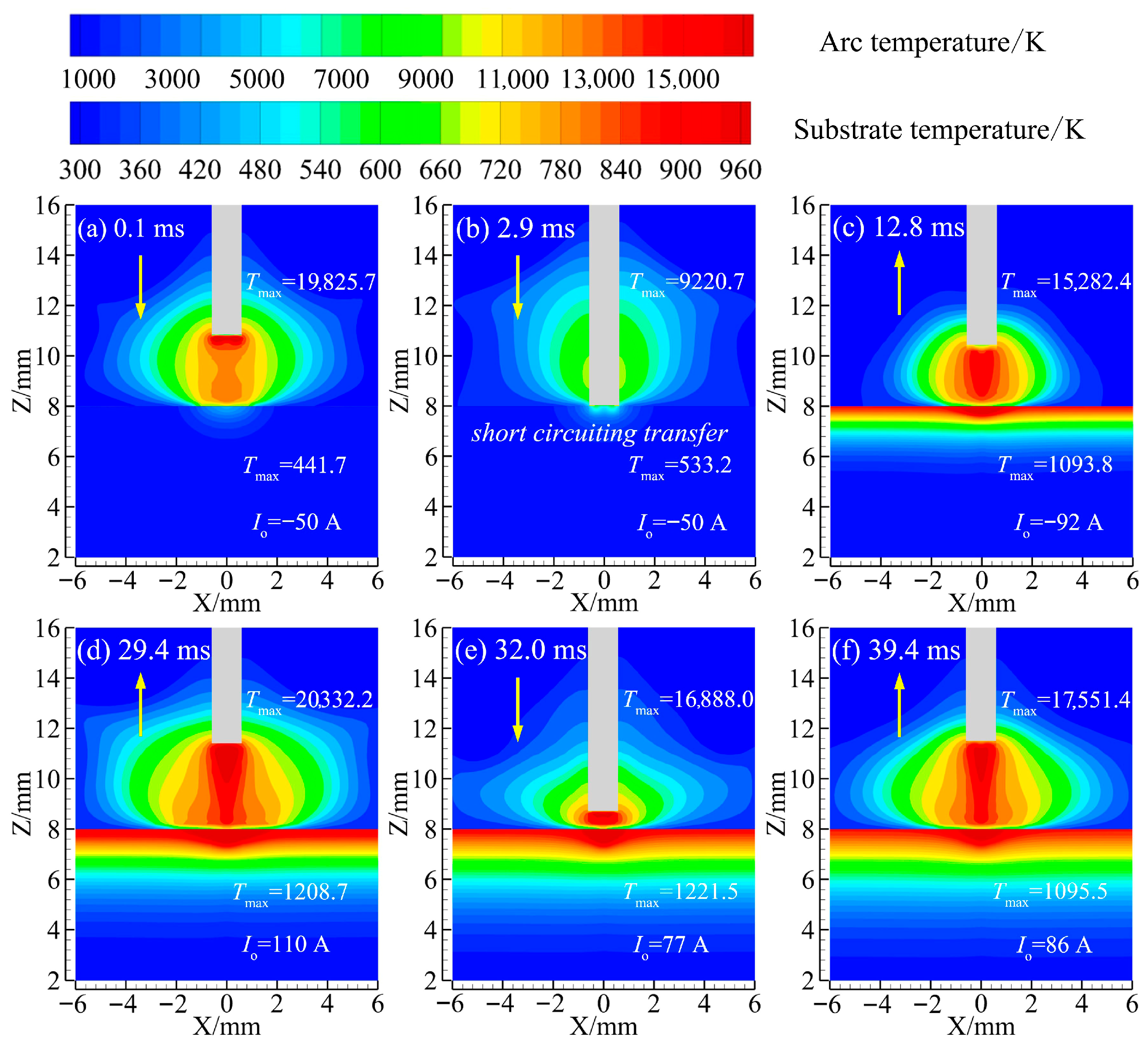

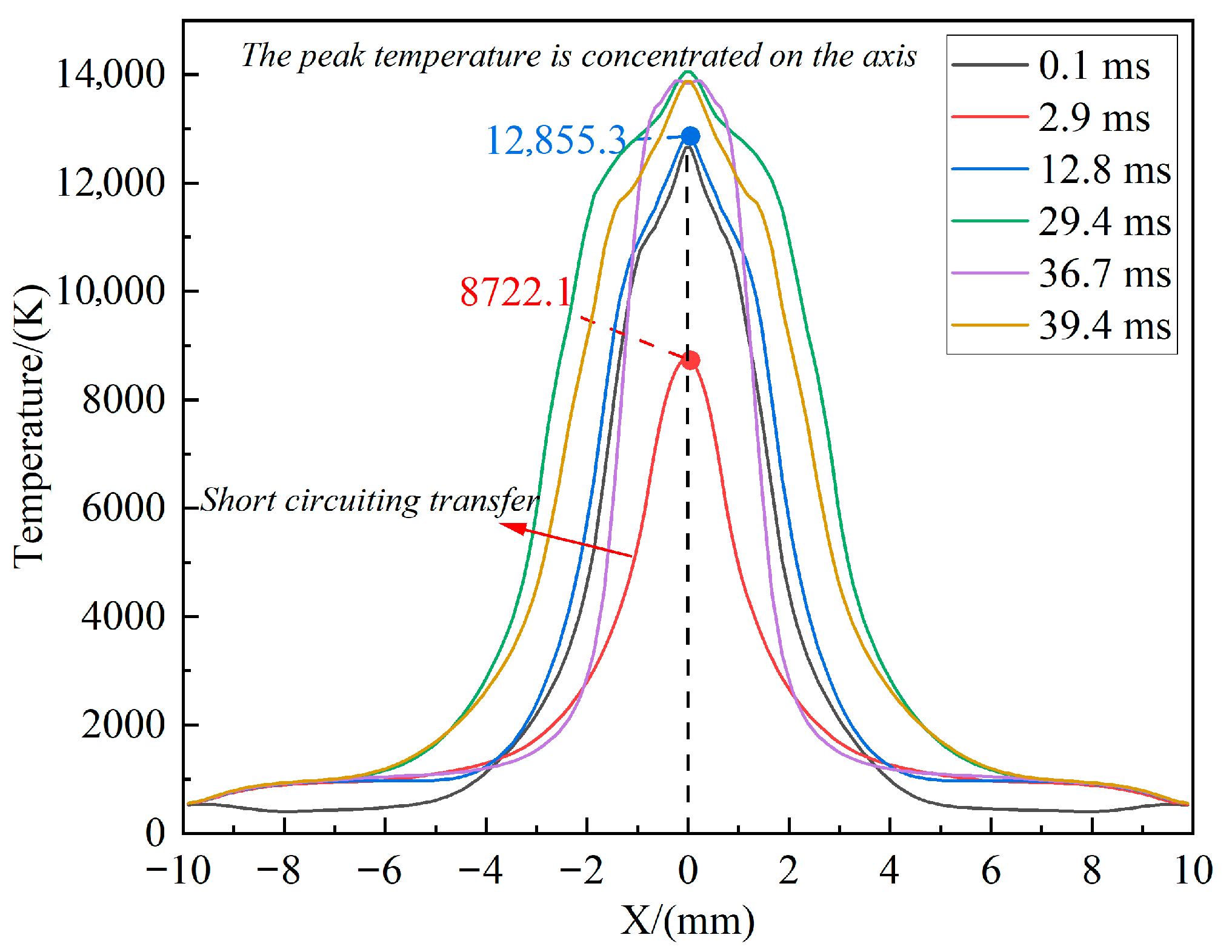

- In the EP to EN stages, EP and EN stages of the peak arc temperature are close, but the EP stage of the high-temperature zone range is wider, and the EN stage is narrower, with a more than 4000 K arc high-temperature zone distribution range of the EP stage. Meanwhile, the EN stage of the arc distribution radius is larger than 1 mm, increasing 40%., and the overall arc temperature is also higher. In addition, from EN to EP stages, the EP stage arc peak temperature is slightly greater than that in the EN stage, the distribution range of the high-temperature zone distribution in the same EP stage is wider, and the distribution range of the high-temperature zone distribution range in the EP stage is greater than that in the EN stage, reaching 1.5 mm and increasing 60%, and the overall arc temperature is greater than that in EN stage.

- (2)

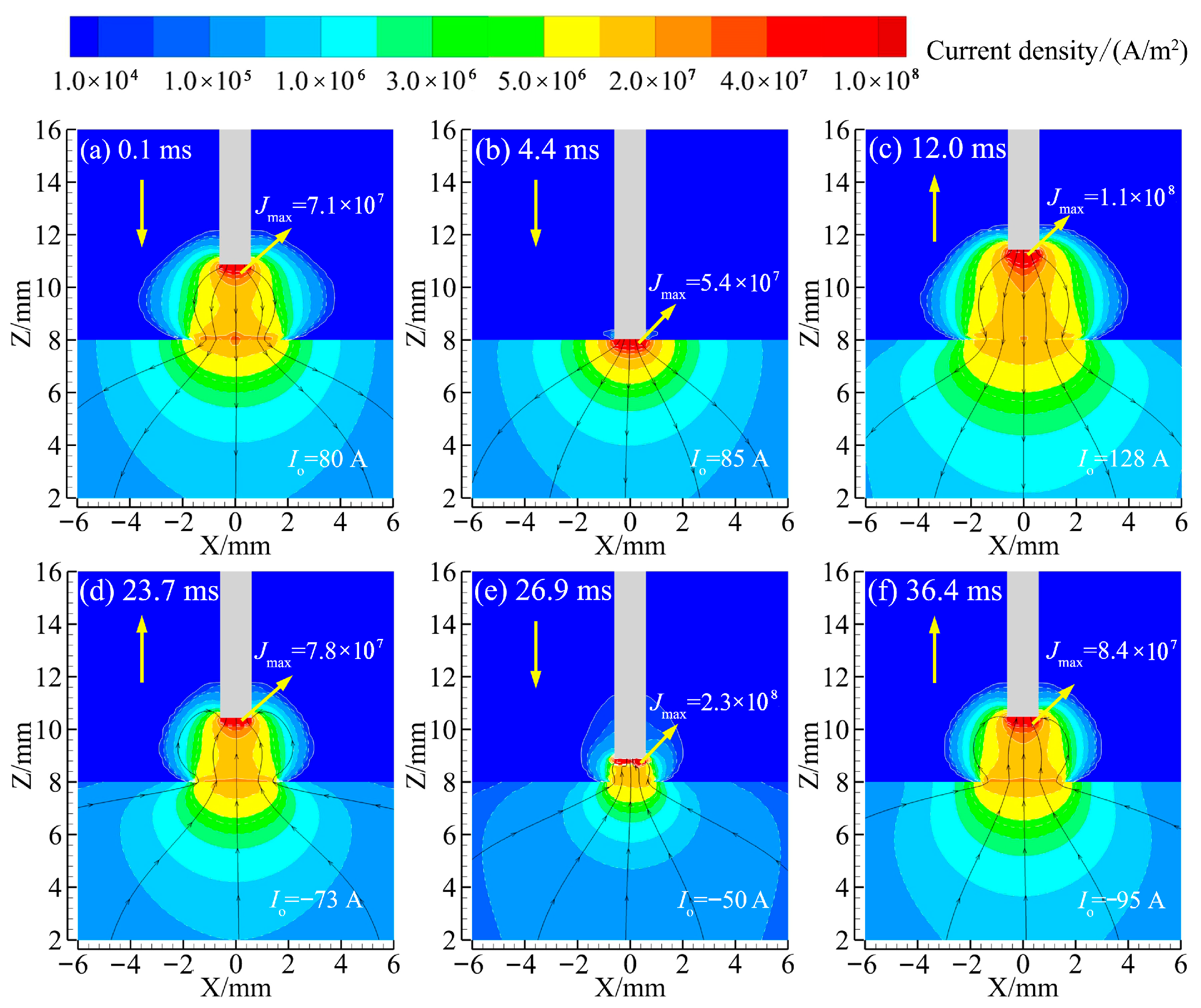

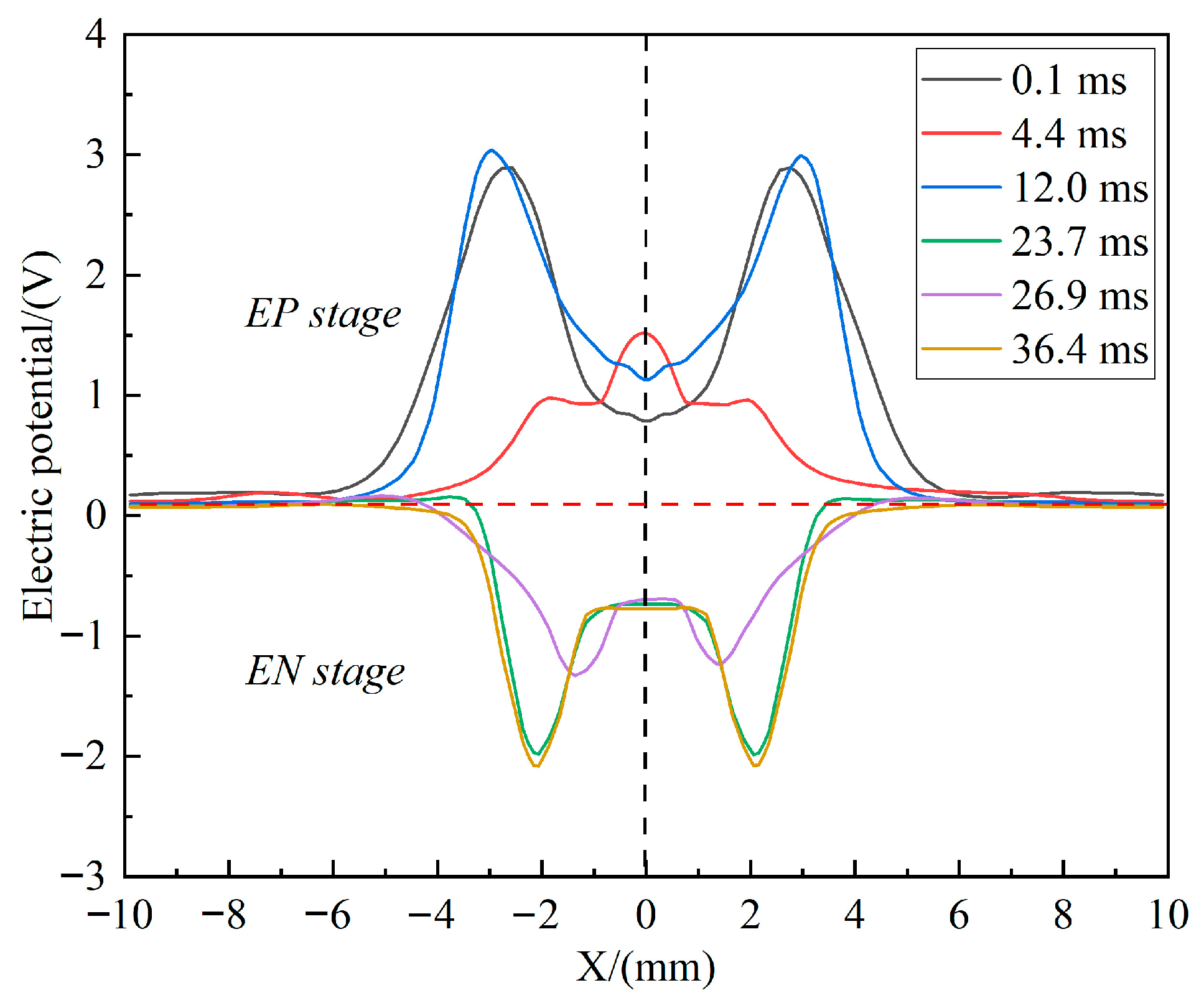

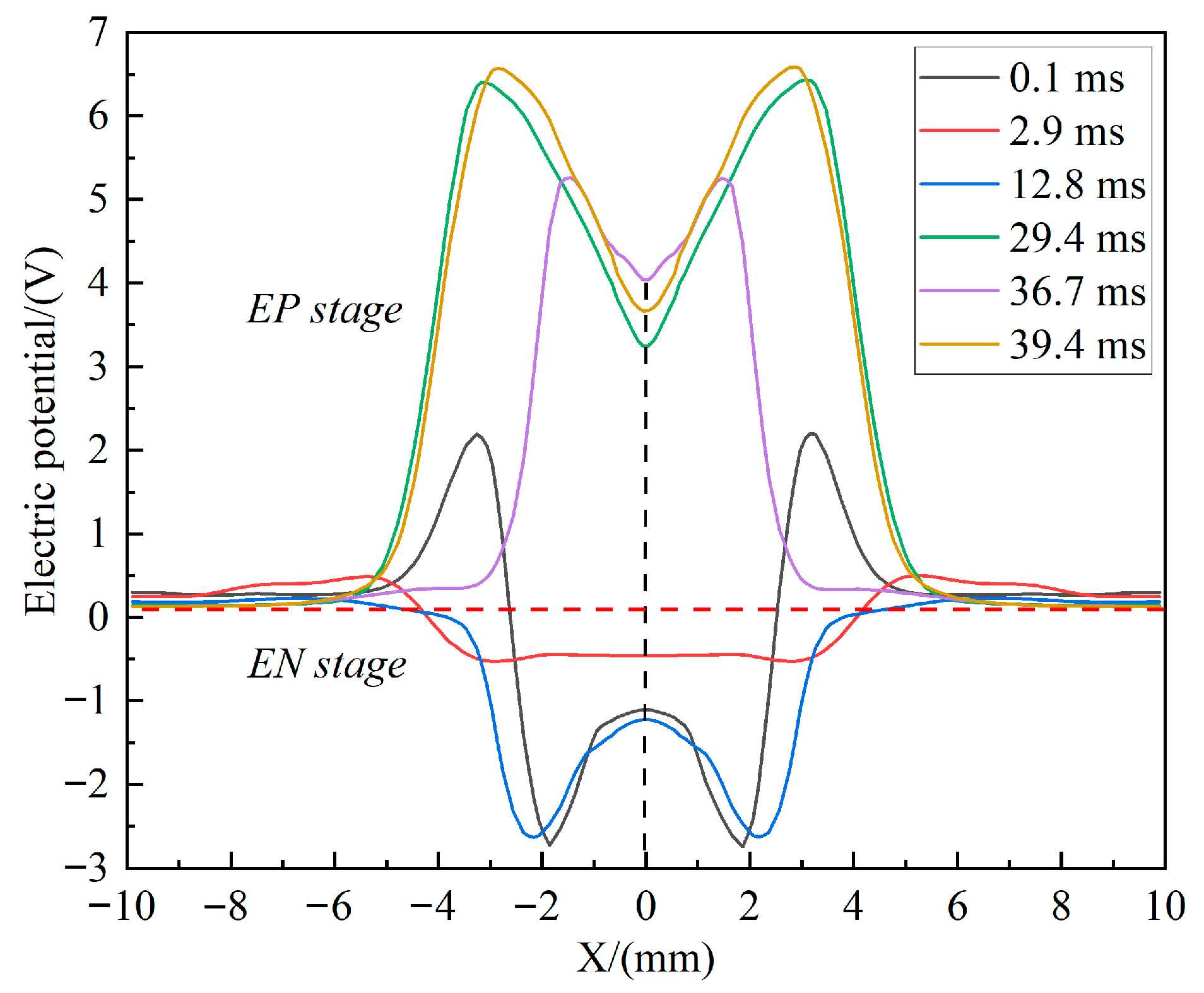

- Compared with EP stage, EN stage exhibits distinct arc characteristics due to the opposite polarity of the electrodes. As shown in the potential distribution diagrams, the arc during the EN stage forms a “wrapped” contraction arc, resulting in a smaller heat transfer area within the molten pool (characterized by a narrower high-potential region). In contrast, the arc during the EP stage assumes a more “bell-shaped” expansion form, leading to a larger heat transfer area at the bottom of molten pool (indicated by a wider high-potential region). Additionally, arc stability is greater during the EN to EP transition than during the EP to EN transition, as evidenced by the more linear current density distribution converging toward the axis.

- (3)

- Electrode spacing significantly affects arc characteristics. During the EN stage, a reduction in electrode spacing results in a more concentrated high-temperature region, with the peak temperature increasing markedly from 15,352.8 K at high spacing to 24,640.3 K at low spacing, an increase of 60.5%. Similarly, the peak current density rises substantially from 7.8 × 107 A/m2 at high spacing to 2.3 × 108 A/m2 at low spacing, increasing 295%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsu, K.C.; Etemadi, K.; Pfender, E. Study of the free-burning high-intensity argon arc. J. Appl. Phys. 1983, 54, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B. The effects of metal vapour in arc welding. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 434001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B.; Tanaka, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Tashiro, S.; Sato, T.; Lowke, J.J. Modelling of thermal plasmas for arc welding: The role of the shielding gas properties and of metal vapour. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 194006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Huang, Z.C.; Huang, J.J.; Wang, X.X.; Huang, Y. Three-dimensional numerical analysis of the interaction between arc and molten pool in tungsten inert gas welding considering metal vapor. Acta Phys. Sin. 2015, 64, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Fan, D.; Huang, J.K. Tungsten cathode-arc plasma-weld pool interaction in the magnetically rotated or deflected gas tungsten arc welding configuration. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Fan, D.; Huang, J.K. Numerical study on arc plasma behaviors in GMAW with applied axial magnetic field. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 074502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Y.M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.R.; Lu, X. Numerical investigation on the influence of current waveform on droplet transfer in pulsed gas metal arc welding. Vacuum 2022, 203, 111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Zhang, H.; Jia, J.P.; Wu, J.Z. Numerical simulation of CMT welding arc morphology and temperature field based on dynamic grid. Hot Work Technol. 2017, 46, 241–243+246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadiou, S.; Courtois, M.; Carin, M.; Berckmans, W. 3D heat transfer, fluid flow and electromagnetic model for cold metal transfer wire arc additive manufacturing (Cmt-Waam). Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.Y.; Wang, L.L.; Gao, Z.N.; Dou, Z.W.; Ben, Q.; Gao, C.Y.; Zhan, X.H. Study on the mechanism of influence of arc characteristics on droplet transfer behavior in CMT arc additive manufacturing process. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Y.; Tashiro, S.; Murphy, A.B.; Tanaka, M.; Liu, X.B.; Wei, Y.H. Deepening the understanding of arc characteristics and metal properties in GMAW-based WAAM with wire retraction via a multi-physics model. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 97, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, G.; Anand, P.I.; Sahu, A.; Singh, I.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Tamang, S.K. Enhance the microstructure and mechanical properties of directed energy deposition-Arc (DED-Arc) stainless steel 308L using laser shock peening process. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 8537–8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, G.; Tamang, S.K.; Patel, M.S.; Narayanan, J.A.; Pallagani, J.; Rose, P.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Thirugnanasambandam, A.; Anand, P.I. Post-processing treatment of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured NiTi shape memory alloy using laser shock peening process: A study on tensile behavior and fractography analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 3315–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, G.; Tamang, S.K.; Badhai, J.; Karthik, S.; Narayanan, J.A.; Thirugnanasambandam, A.; Sonawane, A.; Anand, P.I. Post-processing of wire-arc additive manufactured stainless steel 316 l bone staples using laser shock peening: A mechanical and antibacterial study. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 5525–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Research on the Forming Process of Aluminum Alloy CMT-PADV Arc Additive Manufacturing. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia University of Technolog, Hohhot City, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, F.M.; Teixeira, F.R.; Da Silva, L.J.; De Araújo, D.B.; Reis, R.P.; Scotti, A. Thermal management in WAAM through the CMT advanced process and an active cooling technique. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadiou, S.; Courtois, M.; Carin, M.; Berckmans, W.; Le Masson, P. Heat transfer, fluid flow and electromagnetic model of droplets generation and melt pool behaviour for wire arc additive manufacturing. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 148, 119102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Wu, D.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H. Heat and mass transfer behavior in CMT plus pulse arc manufacturing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 281, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Qi, C.Q.; Zhao, K.; Hao, Y.B.; Du, Y.; Huang, Y.L. Additive manufacturing technology of large aerospace aluminum alloy load-bearing components. Electr. Weld. Mach. 2022, 51, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Lowke, J.J. Predictions of weld pool profiles using plasma physics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 40, R1–R23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traidia, A. Multiphysics Modelling and Numerical Simulation of GTA Weld Pools. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Physical Field | Internal Boundary of the Cathode |

|---|---|

| electromotive force | be coupled (with sth) |

| magnetic fields | be coupled (with sth) |

| energies | arc plasma side: Tcp; substrate side: Equation (12) |

| momentum | baseboard side: Equations (16) and (17) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, X.; Yin, H.; Liu, L.; Han, Y. Numerical Simulation of Arc Characteristics of VP-CMT Aluminum Alloy Arc Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2025, 15, 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121360

Bao X, Yin H, Liu L, Han Y. Numerical Simulation of Arc Characteristics of VP-CMT Aluminum Alloy Arc Additive Manufacturing. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121360

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Xulei, Hang Yin, Lele Liu, and Yongquan Han. 2025. "Numerical Simulation of Arc Characteristics of VP-CMT Aluminum Alloy Arc Additive Manufacturing" Metals 15, no. 12: 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121360

APA StyleBao, X., Yin, H., Liu, L., & Han, Y. (2025). Numerical Simulation of Arc Characteristics of VP-CMT Aluminum Alloy Arc Additive Manufacturing. Metals, 15(12), 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121360