Design of Novel Non-Cytotoxic Ti-15Nb-xTa Alloys for Orthopedic Implants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ti-15Nb-Ta Alloys Production

2.2. Chemical Characterization

2.3. Structural Characterization

2.4. Mechanical Properties

2.5. Cell Culture and Viability Assay

2.6. Cell Adhesion Assay

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

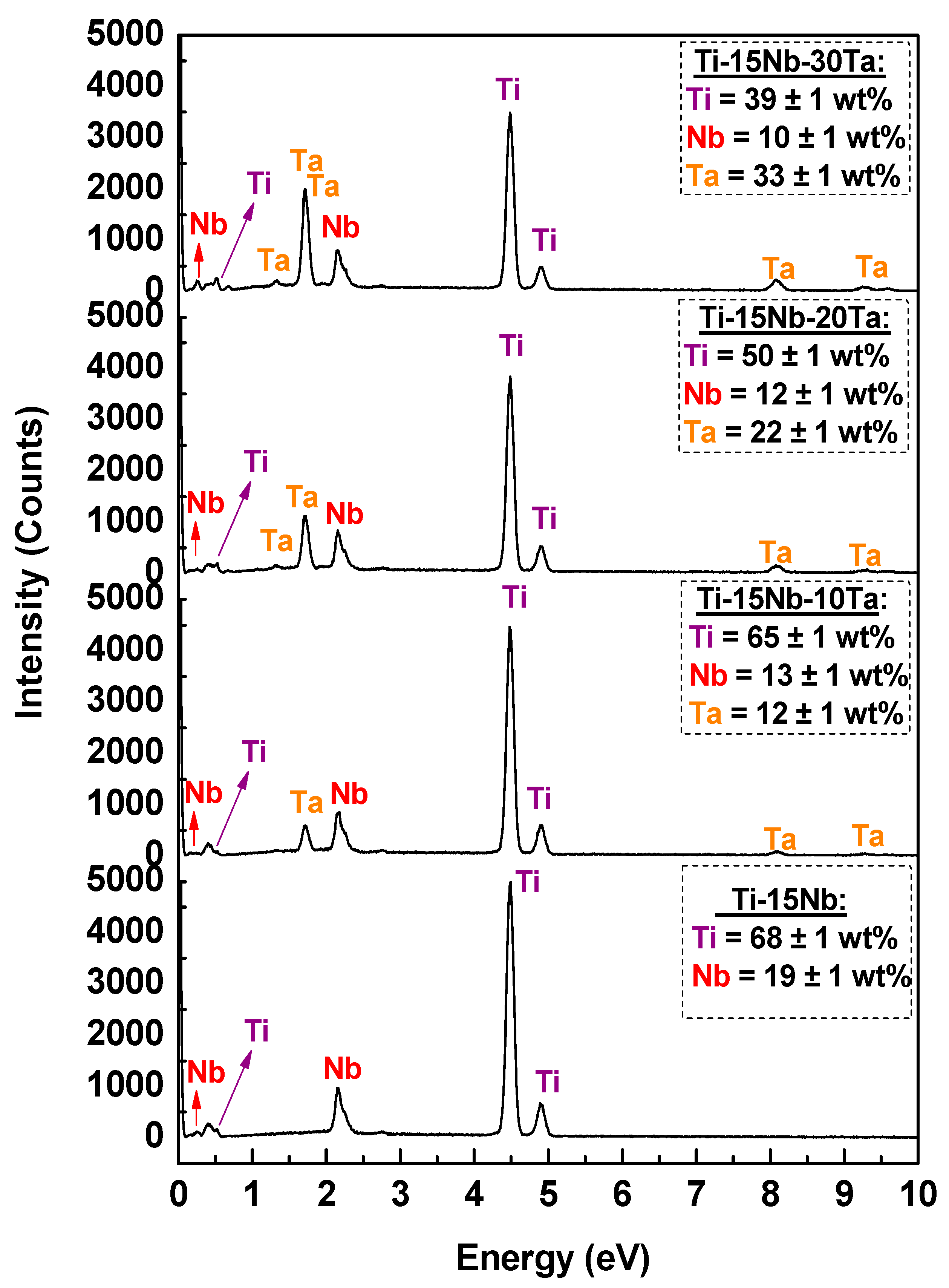

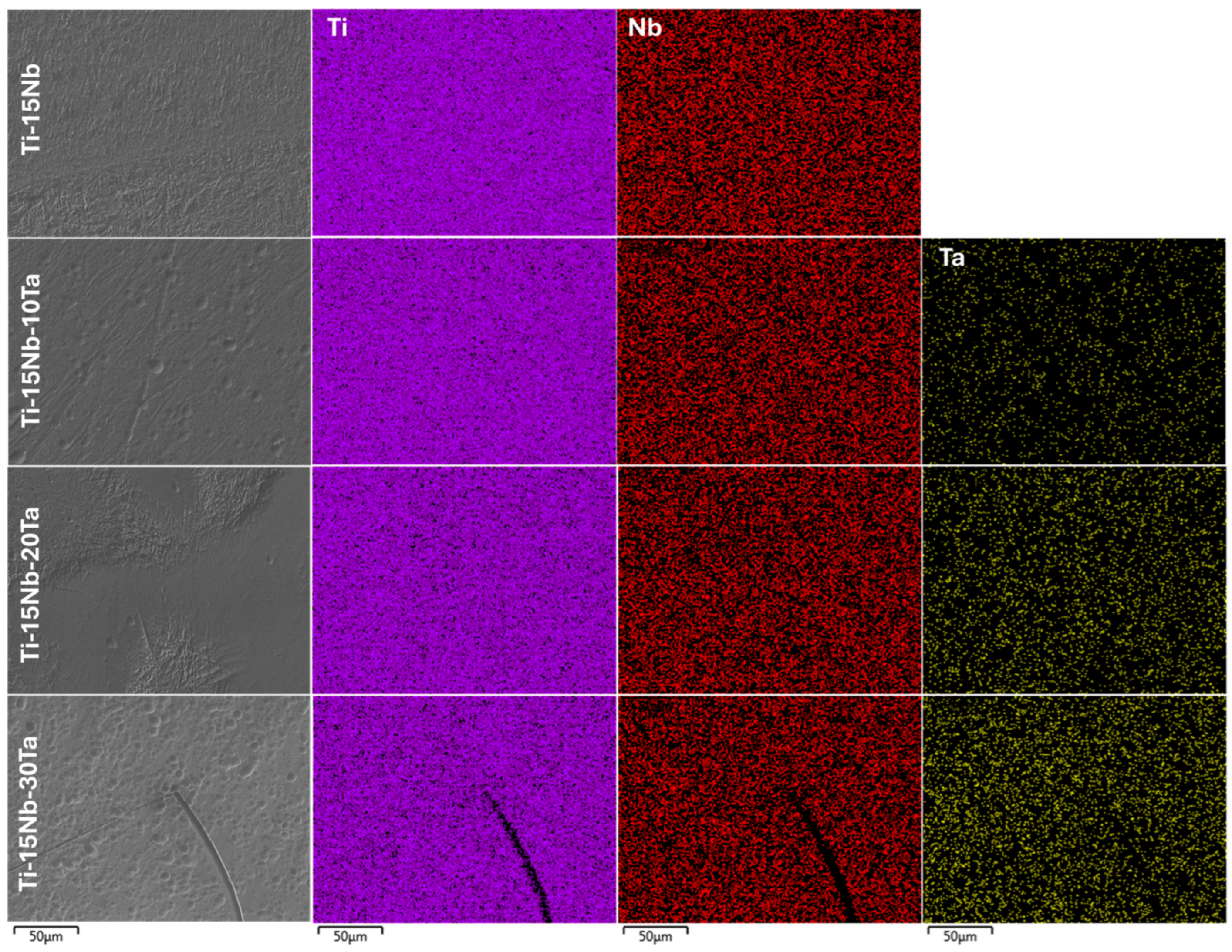

- The alloys were successfully cast, yielding high-quality materials with excellent homogeneity, as evidenced by the chemical composition analysis (EDS). Niobium contributes to the stabilization of the β phase in combination with tantalum.

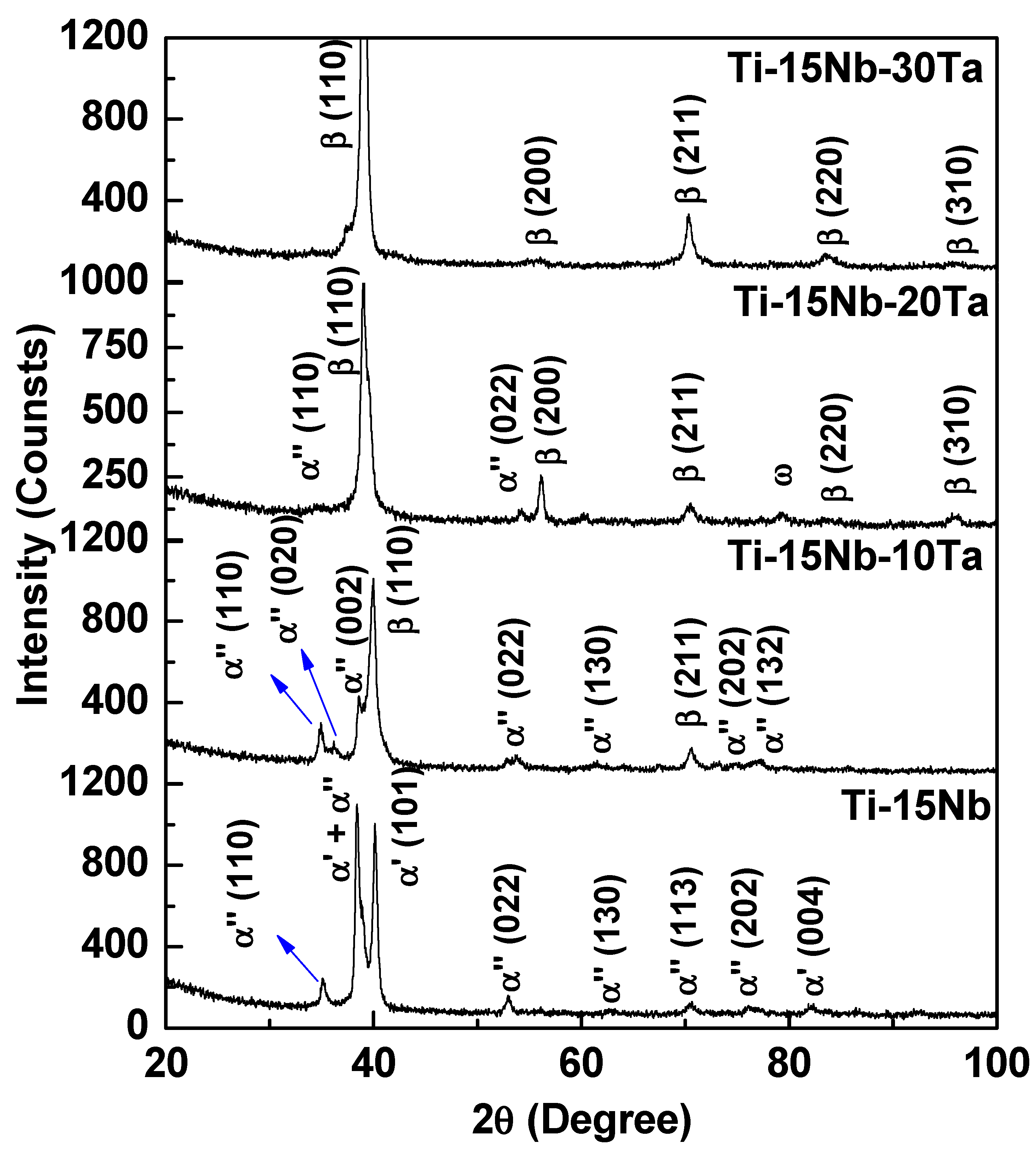

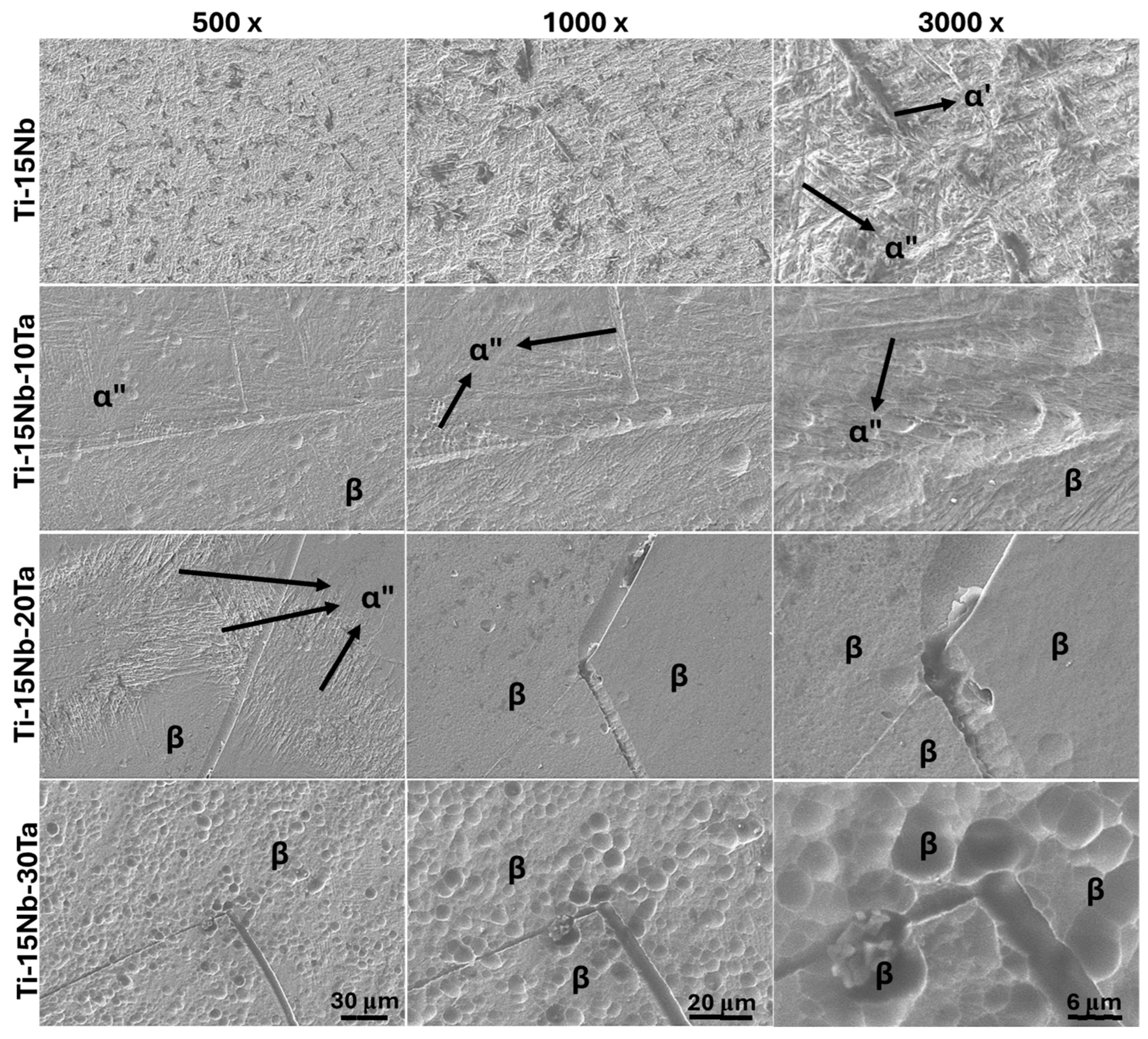

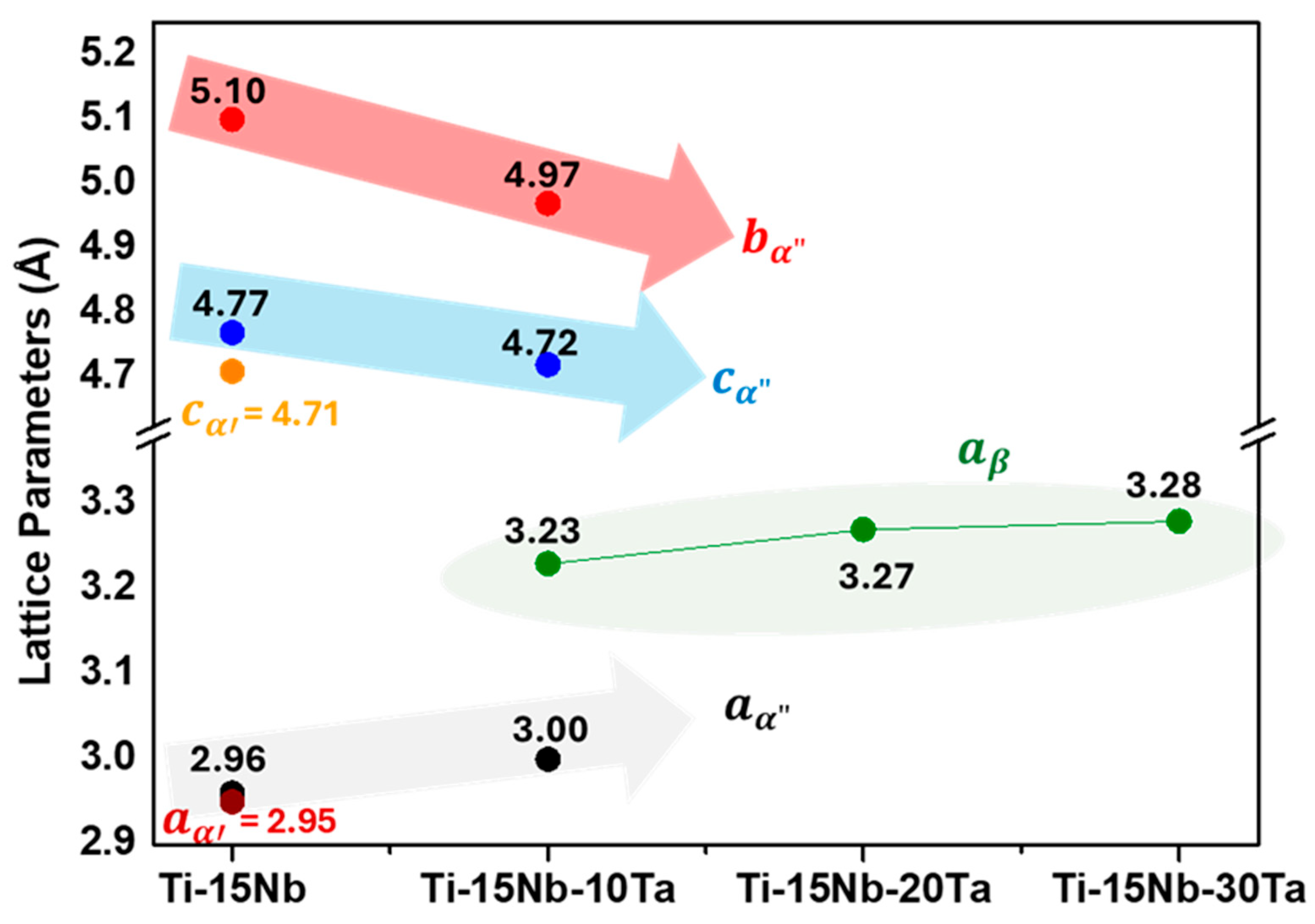

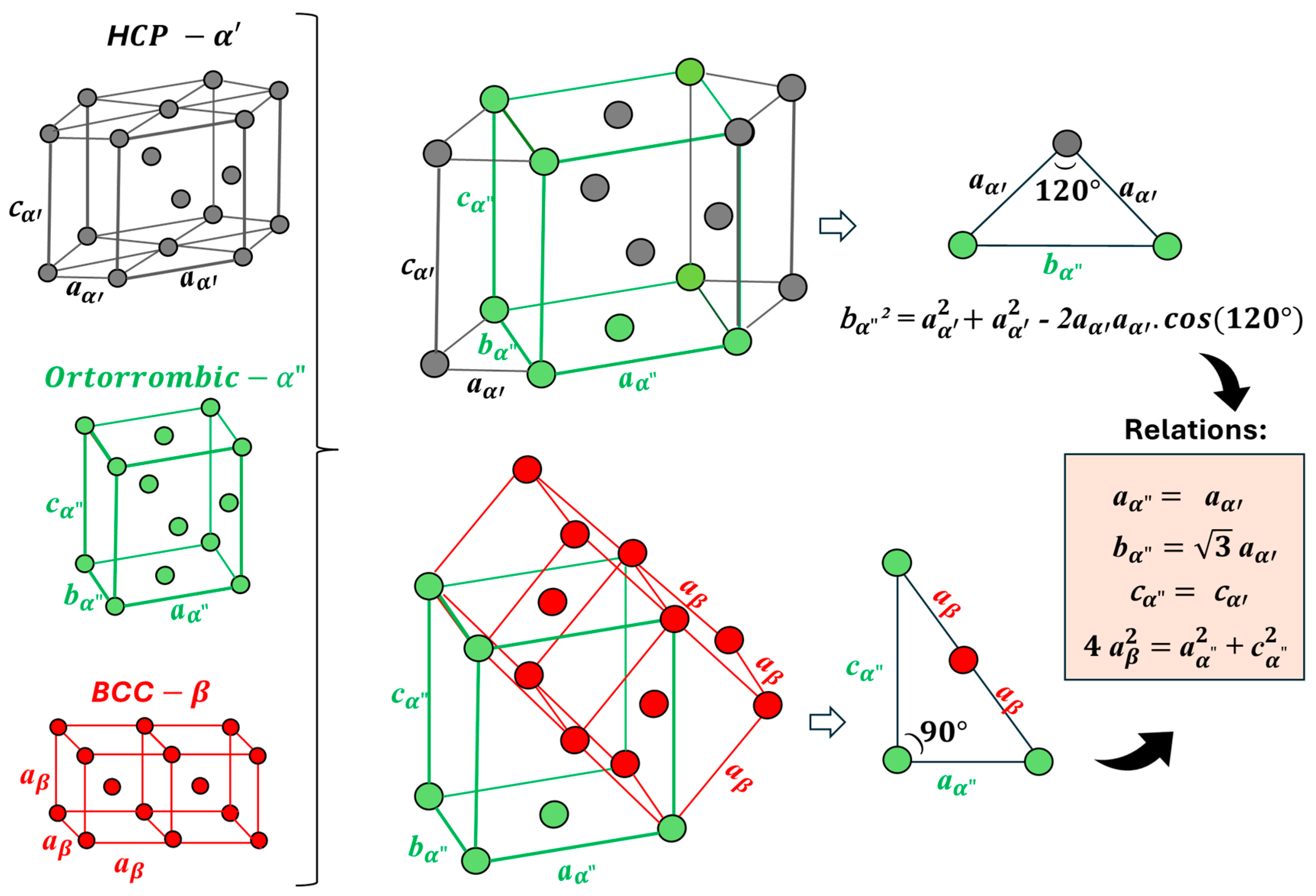

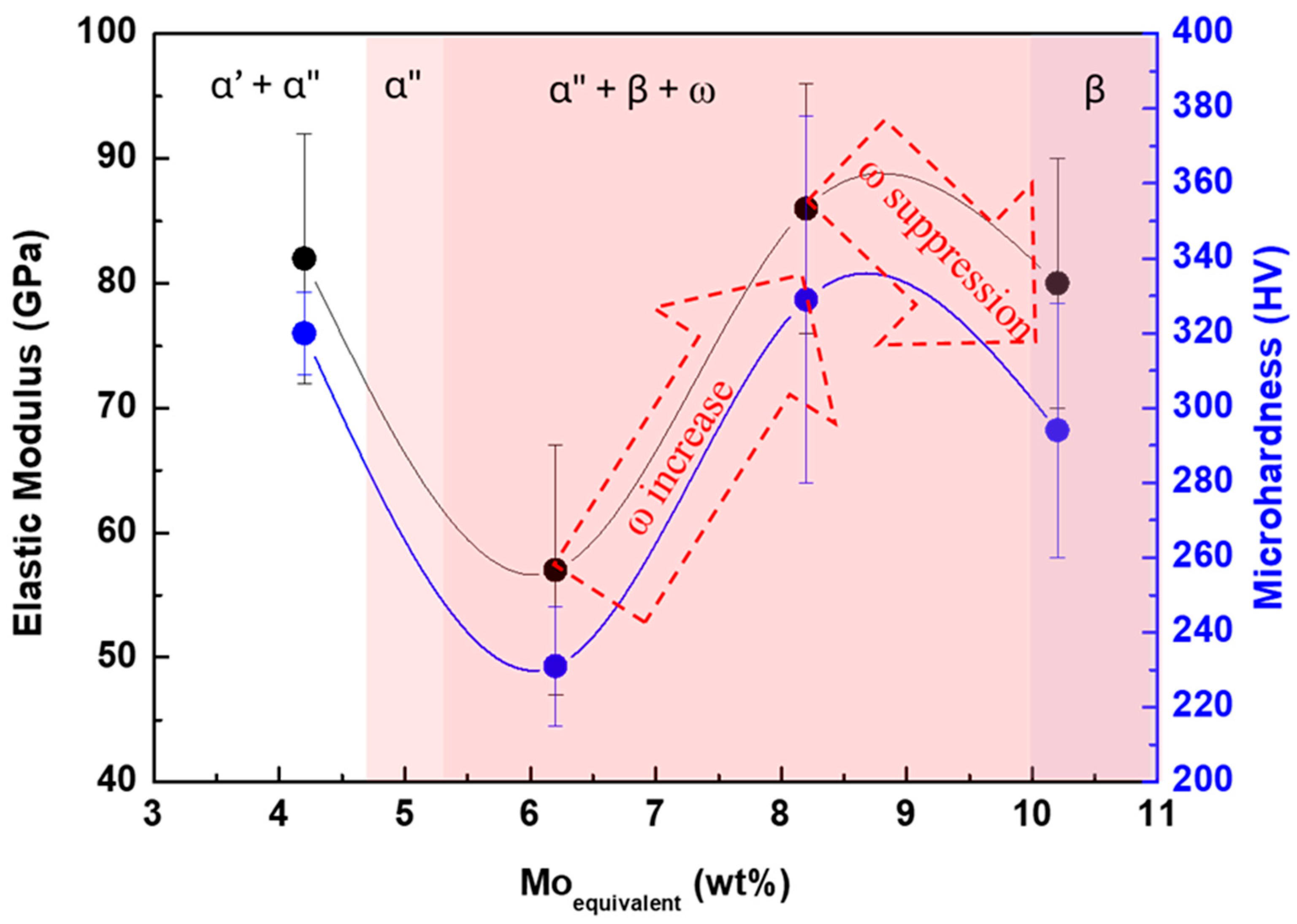

- Structural and microstructural analyses revealed that the Ti-15Nb alloy consists of α′ and α″ phases; Ti-15Nb-10Ta exhibits α″ and β phases; Ti-15Nb-20Ta contains α″, β, and ω phases, with β being predominant; Ti-15Nb-30Ta is fully β. The addition of Ta increases the lattice parameter of the β phase and decreases the b and c lattice parameters while increasing the a parameter of the α″ phase. The Mo equivalent and molecular orbital theories are effective in predicting the phases formed in the Ti-15Nb-Ta system.

- The microhardness of all alloys is higher than that of CP-Ti due to solid solution strengthening. Ti-15Nb-20Ta exhibits elevated hardness due to ω phase precipitation. The elastic modulus decreases with increasing Ta content due to β phase stabilization and ω phase suppression (values above 30 wt% Ta). Additionally, the presence of the α″ martensitic phase also contributes to lower elastic modulus values. Ti-15Nb-10Ta exhibits the lowest elastic modulus (57 GPa) and hardness (230 HV), indicating the highest potential for orthopedic applications.

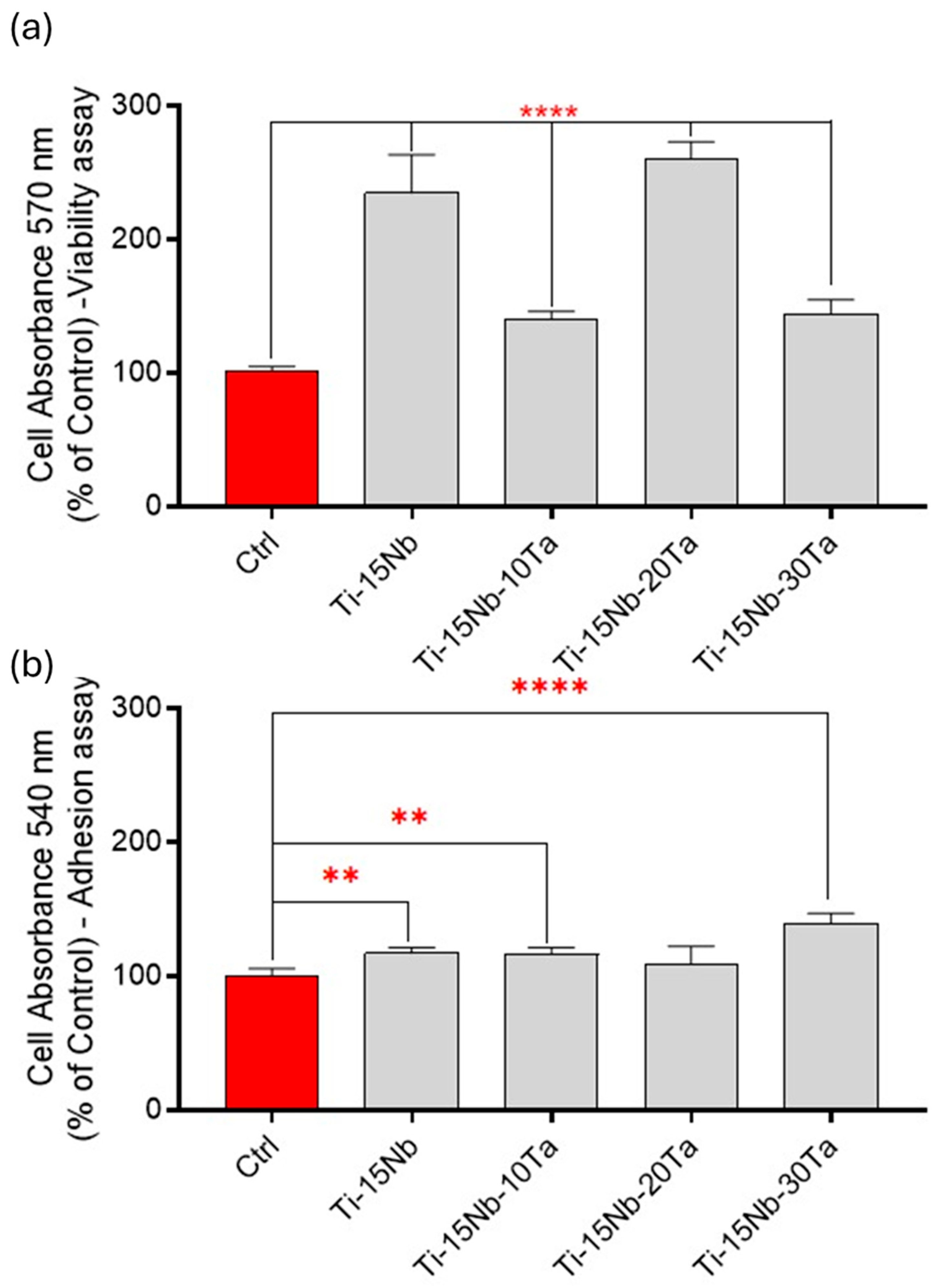

- Biocompatibility tests (MTT, CV, and adhesion via SEM) show that the alloys developed in this work have good biocompatibility with osteoblastic cells.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kacsó, A.-B.; Peter, I. A Review of Past Research and Some Future Perspectives Regarding Titanium Alloys in Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesode, P.; Barve, S. A review—Metastable β titanium alloy for biomedical applications. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapaakala, G.; Subramani, V. A review on β-Ti alloys for biomedical applications: The influence of alloy composition and thermomechanical processing on mechanical properties, phase composition, and microstructure. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2022, 237, 14644207221141768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W. Titanium Alloys for Dental Implants: A Review. Prosthesis 2020, 2, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senopati, G.; Rahman Rashid, R.A.; Kartika, I.; Palanisamy, S. Recent Development of Low-Cost β-Ti Alloys for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Metals 2023, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Panaino, J.V.P.; Santos, I.D.; Araujo, L.S.; Mei, P.R.; de Almeida, L.H.; Nunes, C.A. Characterization of a new beta titanium alloy, Ti–12Mo–3Nb, for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 536, S208–S210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A.K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A.K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants—A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Das, S.; Suwas, S.; Chatterjee, K. Engineering the next-generation tin containing β titanium alloys with high strength and low modulus for orthopedic applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 78, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Yamada, N.; Hanada, S.; Jung, T.-K.; Itoi, E. The bone tissue compatibility of a new Ti–Nb–Sn alloy with a low Young’s modulus. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Gong, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Zhang, X. Strengthening mechanisms of developed biomedical titanium alloys with ultra-high ratio of yield strength to Young’s modulus. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1035, 181530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, D.; Bagno, A. When the Total Hip Replacement Fails: A Review on the Stress-Shielding Effect. Processes 2022, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Jha, I.K.; Singh, J. Recent advances in the aging of β-titanium alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1024, 180098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliza, E.; Wella, S.A.; Amalia, N. Stability and mechanical properties of Ti-Nb-Ta ternary alloys. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 025904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.L.; Niinomi, M.; Akahori, T. Effects of Ta content on Young’s modulus and tensile properties of binary Ti–Ta alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.F.; Rossi, M.C.; Vidilli, A.L.; Amigó Borrás, V.; Afonso, C.R.M. Assessment of β stabilizers additions on microstructure and properties of as-cast β Ti–Nb based alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3511–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D., Jr.; Rethwisch, D.G. Callister’s Materials Science and Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, P.A.B.; Grandini, C.R.; Afonso, C.R. Development of new β Ti and Zr-based alloys in the Ta-(75-x)Ti-xZr system. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4579–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Cui, Y.-W.; Zhang, L.-C. Recent Development in Beta Titanium Alloys for Biomedical Applications. Metals 2020, 10, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.-K.; Kim, J.-Y.; Hwang, M.-J.; Song, H.-J.; Park, Y.-J. Effect of Nb on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, Corrosion Behavior, and Cytotoxicity of Ti-Nb Alloys. Materials 2015, 8, 5986–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, J.-O.; Sellin, M.-L.; Kauertz, E.; Johannsen, J.; Weinmann, M.; Stenzel, M.; Frank, M.; Vogel, D.; Bader, R.; Jonitz-Heincke, A. Advanced Ti–Nb–Ta Alloys for Bone Implants with Improved Functionality. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar, K.; Gopal, V.; Prasanth, S.; Manivasagam, G.; Chatterjee, K.; Suwas, S. Tribocorrosion of biomedical Ti-Nb-Ta alloys fabricated by directed energy deposition using elemental powders. Tribol. Int. 2025, 211, 110906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.; Rossi, M.C.; Afonso, C.R.M.; Grandini, C.R.; Kuroda, P.A.B. Development and functionalization of novel Ti–20Nb–Ta alloys for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 3127–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, P.A.B.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Grandini, C.R. Preparation, Microstructural Characterization, and Selected Mechanical Properties of Ti-20Zr-2.5Mo and Ti-20Zr-7.5Mo Used as Biomaterial. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 869, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaha, I.; Alves, A.C.; Affonço, L.J.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; da Silva, J.H.D.; Rocha, L.A.; Pinto, A.M.P.; Toptan, F. Corrosion and tribocorrosion behaviour of titanium nitride thin films grown on titanium under different deposition times. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 374, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Drew, M.G.B. Comparison of calculations for interplanar distances in a crystal lattice. Crystallogr. Rev. 2017, 23, 252–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E92-17; Standard Test Methods for Vickers Hardness and Knoop Hardness of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM E1876-22; Standard Test Method for Dynamic Young’s Modulus, Shear Modulus, and Poisson’s Ratio by Impulse Excitation of Vibration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, M.; Wen, C.; Lv, S.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Qu, X. The Mechanical Properties and In Vitro Biocompatibility of PM-Fabricated Ti-28Nb-35.4Zr Alloy for Orthopedic Implant Applications. Materials 2018, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM F2066-13; Standard Specification for Wrought Titanium-15 Molybdenum Alloy for Surgical Implant Applications (UNS R58150). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mattos, F.N.d.; Kuroda, P.A.B.; Rossi, M.C.; Afonso, C.R.M. Wear Behavior of Ti-xNb Biomedical Alloys by Ball Cratering. Mater. Res. 2024, 27, e20230494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, Q.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Effects of Mo equivalent on the phase constituent, microstructure and compressive mechanical properties of Ti–Nb–Mo–Ta alloys prepared by powder metallurgy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Niu, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, Z.; Dan, Z.; Chang, H. Relative strength of β phase stabilization by transition metals in titanium alloys: The Mo equivalent from a first principles study. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, M.; Xu, Z. Research on the microstructure and properties of Ti-VMoCrZrAl alloys with different Mo equivalents. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1044, 184055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.F.; Ju, C.P.; Chern Lin, J.H. Structure and properties of cast binary Ti–Mo alloys. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, T.A.G.; Sousa, K.; Kuroda, P.A.B.; Grandini, C.R. A New α + β Ti-15Nb Alloy with Low Elastic Modulus: Characterization and In Vitro Evaluation on Osteogenic Phenotype. J Funct Biomater 2023, 14, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.M.G.; Souza, E.A.d.; Silva, M.S.C.d.; Matos, G.R.L.; Batista, W.W.; Souza, S.A.S.d.A. Role of Silicon in the Microstructural Development and Properties of Ti-15Nb-xSi Alloys for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaga, M.; Kato, M.; Kamimura, T.; Fukumoto, M.; Harada, I.; Kubo, K. Theoretical design of beta-type titanium alloys. In Titanium’92: Science and Technology; Minerals, Metals and Materials Society: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, D.; Niinomi, M.; Morinaga, M.; Kato, Y.; Yashiro, T. Design and mechanical properties of new β type titanium alloys for implant materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 243, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S.; Singh, H.; Gepreel, M.A.-H. A review on alloy design, biological response, and strengthening of β-titanium alloys as biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 121, 111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hady, M.; Hinoshita, K.; Morinaga, M. General approach to phase stability and elastic properties of β-type Ti-alloys using electronic parameters. Scr. Mater. 2006, 55, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Banumathy, S.; Sankarasubramanian, R.; Singh, A.K. Orthorhombic martensitic phase in Ti–Nb alloys: A first principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 83, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogi, H.; Kai, S.; Ledbetter, H.; Tarumi, R.; Hirao, M.; Takashima, K. Titanium’s high-temperature elastic constants through the hcp–bcc phase transformation. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 2075–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schumacher, Y.M.; Grandini, C.R.; de Almeida, G.S.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Kuroda, P.A.B. Design of Novel Non-Cytotoxic Ti-15Nb-xTa Alloys for Orthopedic Implants. Metals 2025, 15, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111201

Schumacher YM, Grandini CR, de Almeida GS, Zambuzzi WF, Kuroda PAB. Design of Novel Non-Cytotoxic Ti-15Nb-xTa Alloys for Orthopedic Implants. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111201

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchumacher, Yasmin Monteiro, Carlos Roberto Grandini, Gerson Santos de Almeida, Willian Fernando Zambuzzi, and Pedro Akira Bazaglia Kuroda. 2025. "Design of Novel Non-Cytotoxic Ti-15Nb-xTa Alloys for Orthopedic Implants" Metals 15, no. 11: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111201

APA StyleSchumacher, Y. M., Grandini, C. R., de Almeida, G. S., Zambuzzi, W. F., & Kuroda, P. A. B. (2025). Design of Novel Non-Cytotoxic Ti-15Nb-xTa Alloys for Orthopedic Implants. Metals, 15(11), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111201