1. Introduction—Why this Paper?

In all areas of work (academic and practical) related to disaster risk, climate change and development more generally, the term

community and its adjunct

community-based have become the default terminology when referring to the local level. They are applied extensively to highlight what is believed to be a people-centred, participatory, bottom-up or grassroot-level approach to dealing with a wide range of challenges, including the mitigation of hazards. In fact, ‘community’ is one of the most widely invoked concepts in a range of uses by academics, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), aid donors and international organisations. It is used “in a bewildering variety of ways” [

1] (p. 182), very often without reflection on its meaning, or even a definition. It has therefore taken on a life of its own, based on what can be considered a ‘moral licence’ that supposedly guarantees that the actions being taken are genuinely people-centred and ethically justified (or even mandatory). Apart from our focus (on disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA)), the terminology is used in many other arenas of development.

Community-based can be found as a prefix for natural resource management, ecosystem management, health, tourism management, water and sanitation, conservation, protection (in regard to rights), development and the rest.

Community-related concepts began to be increasingly used in development and disaster management in the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting how bottom-up approaches and the local level came into vogue in both academic and practical circles. Today, many government and non-government organisations, donor agencies and researchers claim to be working ‘with the people’, i.e., local groups, households or individuals, to understand and mitigate disaster impacts, promote climate change adaptation and improve livelihoods. The idea behind this approach is quite simple: it is difficult to do much wrong when involving the ‘community’ in humanitarian action or when doing research, while outside interventions or those involving top-down ideas may well cause harm or be met by resistance from the ‘locals’.

Despite, or actually because of, its inherent ambiguity, the term ‘community’ tends to be used more frequently and more widely and loosely than ever before [

2]. Referring to ‘local’ or ‘place-based’ communities displays a rather one-dimensional and static understanding of community, ignoring social dynamics and the multiple, sometimes conflicting, layers of meaning that are embedded in the term. This is not a new observation, really: already in the early 2000s, Walmsley [

3,

4], in referring to Dalton et al. [

5]—and thus even several more decades back—speaks of the term’s high level of use but low level of meaning. Yet, ‘community’ is still extremely popular in research or development and humanitarian action but barely ever being reflected upon critically. It is so widely invoked that “cross-disciplinary confusion seems to be the order of the day” [

1] (p. 182). For this reason, questions must be raised about the extent to which the predominant idea of ‘community’ is still viable or adequate as a way of development or DDR intervention and CCA activities.

This paper aims to analyse the way the concept of ‘community’ is used, to reflect on the problems that come with it, and to argue for a more powerful and relevant form of analysis that does not avoid looking at the causes of problems that outside organisations claim they want to address. We challenge the assumption that ‘community-based’ development and DRR work will, as a matter of fact, do good. Indeed, one of our main concerns about the way ‘community’ is often used both by scholars and practitioners is that it disguises or even enables the ignoring of the reasons why disasters happen: it is an obstacle for understanding causation and explaining why people are vulnerable and exposed to hazards. One of the main reasons for this paper is to make an intervention that highlights the need to understand what causes vulnerability to hazards, and we consider that, in general, using the concept ‘community’ uncritically does not support the goal of explanation of the relevant causation.

This could be considered to operate on a spectrum: at one end are organisations that want to avoid dealing with causation, and find the concept ‘community’ of great assistance in providing a ready-made body of people (in a location) who can be assumed to have a common interest. At the other end of the spectrum are organisations and individuals who want to support the self-organising capacity and ‘grassrooted-ness’ of people at the local level, and who have a basic notion of wanting to support the ‘most vulnerable’ (and poorest) as a moral objective. In many cases, these two ends of the spectrum become mutually supportive when the latter are dependent on funding from the former; organisations that want to be based on ‘bottom-up’ work find that some donors are very willing to fund disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation when it involves the moral claim of ‘grassrooted-ness’. The same sometimes holds true for academia; ‘doing research’ with the people, e.g., in the form of participatory field work, is often considered to produce more credible data irrespective of the question who these ‘people’ are and whether or not they represent a consistent body of individuals sharing the same ideas, perceptions and interests.

Our concern is that the type of grassrooted-ness that is involved in using ‘community’ as the entry point for a study or an intervention (in DRR or in any area of development or adaptation—often prefixed ‘community-based’) fails to deal with causes. The main problems of this kind of grassrooted-ness are the ways it avoids examining the heterogeneity of ‘communities’. These include the divisions, conflicts and oppressions that are significant causes of the problems that researchers are intending to identify, or external agencies are wanting to deal with. In much of the rural so-called developing world (where the terminology of ‘community’ and ‘community-based’ is most widely applied) a significant part of the reasons why some people are poor and vulnerable are processes of exploitation and oppression that are going on within the so-called ‘community’. In other words, using the terminology itself is in danger of diverting attention from the causes of the very problems being addressed, and instead substituting a framing of the problems that avoids looking at their causation.

This paper is concerned with the way that the term ‘community’ embodies an assumption of a ‘collective actor’ that is available to be involved in various types of intervention that are labelled ‘community-based’. We want to promote the understanding of the factors and processes that are internal to a ‘community’ and actually are significant causes of vulnerability. We raise significant doubts about the notion of ‘community’ as being a homogeneous group of people sharing mutual interests, or a social network merely defined by location. These are blurry, unidimensional, undifferentiated and probably outdated constructions of ‘community’, and by employing these, aid agencies or any other outside actors dealing with disaster-related issues will not be able to address local people’s views and needs appropriately since the nature of actions at the local level is shaped through the worldviews of the outsiders.

Despite our scepticism, we are not entirely against ‘community’ concepts as such. We are wary of the simplistic assumption that there is a ‘community’—assumed by outsiders that it automatically must exist in a place—and of the dangerous implications this might have for development and humanitarian action (and related scholarly work). This paper, therefore, aims at contributing to a better understanding of the pitfalls, and potentials, of the ‘community’ idea by uncovering the notions of ‘community’ in the context of DRR, CCA, and development studies and action in general. Our approach is to first consider how ‘community’ has become popular with humanitarian agencies and other organisations, how these are aware of the problems of ‘community’, and to explain how ‘community’ concepts are invoked in practical development work in the context of risks and disasters. This will then be followed by a more detailed analysis of the various, and at times controversial, conceptualisations and meanings of ‘community’. Here we will also highlight the complexity (and blurriness) of ‘community’. We believe that this ‘archaeology’ of community theory and concepts is necessary to better understand the challenges of building humanitarian action and development intervention on an undifferentiated foundation of ‘community’. We will then draw on the implications of the many layers of ‘community’ for research and development or humanitarian action. We will show how ‘community’ has become a strategic framing tool in academia and with agencies and organisations, and draw on some examples to make our case. Finally, we will explain the practical implications of the heterogeneity of the term for the development of a more meaningful usage in DRR and CCA action. This will involve some concluding remarks about a strong and a weak antagonistic position with regards to the ‘community’ idea.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper emerges from the authors’ work for the World Disasters Report 2014 Focus on Culture and Risk [

6], which stimulated many comments and criticisms by the readership. It is not based on a formal methodology, but represents the result of the significant field experience of the authors in research and projects mostly in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Vietnam, Botswana and Tanzania involving interventions in rural and urban livelihoods, health, disaster preparedness, adaptation to climate change and more general aspects of development. Field work carried out includes, for example, a project on “Drought Management, Livelihoods and Urbanisation in Botswana” (1991–1995), which involved household surveys and focus group discussions on individual and group-related livelihood and coping strategies (e.g., [

7]); a study on the social implications of the HIV and AIDS pandemic in Southern Africa (2004–2010; e.g., [

8,

9]); a project on the “Dynamics of HIV/AIDS and Cultures of Resilience” (2012–2016), e.g., [

10]; a project on disaster risks in Nepal (2001–2005; e.g., [

11]); and a project on climate change adaptation in Bangladesh (e.g., [

12]). In effect, we have been participant observers in development- and disaster-related activities and interventions, during which our concerns have grown about the way the notions of ‘community’ and ‘community-based’ are used by researchers, NGOs, civil society organisations, donors, governments and international organisations. Of course, our research and project activities did not involve a critical assessment of the notion of ‘community’, as this was not a goal that was integral to the work. This paper is very much a response to the problems we have each witnessed in the attempts to fit that work into a ‘community’ framing. During these years and decades, a wide-ranging literature (academic and ‘grey’) has been collected that includes what we consider to be mistaken uses of the concepts, as well as emerging criticisms (including those of ‘participation’), such as Blaikie/Brookfield or Blaikie [

13,

14]. This combination of personal experiences and concern that ‘something is wrong’ has prompted this paper.

To validate these personal concerns, a wide range of academic and grey literature has been reviewed and assessed where the terms ‘community’ or ‘community-based’ are used. This has extended the examination beyond personal experiences and provides a robust analysis (including non-academic sources such as handbooks and guidelines for development work and DRR and CCA intervention, and other documents). In addition to sources we have been aware of from our own research and projects, we searched for journal papers using the terms ‘community’, ‘community based’ and ‘community-based’, with a focus mainly on publications relevant to the ‘Global South’, and to development and disaster studies. To identify the literature to be reviewed, academic search engines (such as Scopus, Google Scholar, Geodok and others), as well as online sources by major IGOs (e.g., UN agencies) and NGOs, were used and scanned systematically for publications containing these terms in the title. In a second round of scans, papers published between 1997 and 1999 referring to ‘people’ or ‘local’ were added to the search to test the popularity of the term ‘community’ against related terminology roughly twenty years ago. This was supplemented by more theoretical sources that discuss concepts of ‘community’, which are mainly located within Western sociology. These are generally not specifically concerned with issues in the Global South, and mostly predate development and humanitarian interventions of the past fifty years.

Other sources include comments by experts and practitioners who have been in projects that use ‘community’, sampled in both online and ‘real’ discussions and workshop and conference debates. Where applicable, sources of these comments are cited below. We published a blog on the listserv of the Society for Conservation Biology’s Social Science Working Group (SSWG) in May 2016, and replies were also included in our analysis in the context of this paper. This blog voiced our concerns about the uncritical use of the ‘community’ concept, although it was not designed to generate responses. Nevertheless, we received about a dozen emails with recounts of readers’ first-hand experiences of ‘community-based’ approaches. Some of these narratives (which we anonymised) will be quoted below.

We use ‘community’ (with quotation marks) to indicate that we are challenging the concept. In general, what we mean is ‘so-called community/communities’. When we are discussing how it is used in literature, i.e., when referring directly to theory and conceptual approaches that use the term, we do not use quotation marks so as to not alter the intended original meaning.

3. Results

3.1. Shifting Roles: How Community Has Become Popular in DRR Action, with Donors and when Framing Development Policies

Over the past forty years or so, there has been a major shift in much of development work, with a move away from ‘top-down’ policies towards a much greater focus on ‘grassroots’ and participatory activities. This arose as a result of a declining confidence that governments could effectively support development through programmes that were detached from the people who were supposed to benefit. Instead, local-scale work emerged in which development actors were supposed to do things with people instead of doing them for and to people. This represented a major change in the culture of development organisations and led to the situation that now seems normal, in that much of development workload is directed, and large portions of donor funding used, at the local scale. Since the 1990s, bottom-up approaches have also been adopted by most institutions that engage in DRR and—most recently—CCA. ‘Community-based’ has become a cover term for several approaches that stems from different scientific and practical traditions and has led to the widespread adoption as a key concept for the practice of disaster preparedness and climate change adaptation at the local level. The approach was initially implemented in low income countries by NGOs followed by international organisations like the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (e.g., [

15]). Building resilience at the local level is now increasingly promoted among local governments in order to strengthen the links between the official disaster management system and community-based organisations [

16]. “This had been accompanied by both a need to achieve more finely-tuned risk assessment and to empower ‘communities’ to govern their own disaster avoidance.” [

17] (p. 442).

There is a long tradition of community-based approaches in other disciplines like forestry, natural resource management, tourism and the health sector (cf., e.g., [

18,

19,

20,

21]), and in development- and disaster-related work, too, the use of the notion of ‘community’ grew rapidly in the 1980s and 1990s. Growing recognition of the need for ‘community’ participation for disaster risk reduction as a basis for ‘resilient communities’ was translated into manifold actions and many initiatives at the local level. Policy-makers and practitioners rapidly adopted ‘community-based’ instead of top-down approaches in disaster management, and more recently in climate change adaptation. Community-based DRR or CCA is often referred to as a ‘bottom-up’ process that claims to involve the most vulnerable groups—in some cases in order to address the root causes of risk and vulnerability. It is also considered to be essential to be ‘community-based’ for long-term impact, local ‘ownership’, and the strengthening of institutional, financial, political and other resources. It is assumed that ‘community participation’ in the development and implementation of plans and activities ensures ownership which contributes to their continuation [

22]. Linkages between local ‘communities’ and higher-level actors were seen to be key to unlocking local capacities, political and economic resources and knowledge required for a reduction in disaster risk—and to reduce costs [

23].

An idealised notion of ‘community’ is often imposed by global or trans-national risk reduction initiatives onto people at the grassroots, and NGOs and agencies have worked on DRR and CCA initiatives at what is generally termed the ‘community level’ for quite some time now, often without a clear concept of what is really meant by that category. Donors and international organisations have supported such grassroots approaches, and an undifferentiated idea of ‘community’ has been adopted as being the right scale and implementing agent for any kind of intervention. The definition that has now emerged de facto is that a ‘community’ is best described as nothing more significant than ‘where we work’. It has become an externally assigned location-based justification for where the outside agency has decided that it wants to make its intervention. It comes with a moral license; a symbolic code that appears to make it people-centred and participatory.

In DRR terminology, the notion of ‘community’ typically refers to a sub-system or a segment of society at the local level (both rural villages and sometimes urban neighbourhoods). This, simultaneously, outlines the level of assessment and implementation or intervention. A ‘community’ is often assumed to be a “social entity” [

24] (p. 7), which implies that it needs to have some common social structures (e.g., shared experiences, social interest) and most often a clearly defined, geographical area. In assuming this, some NGOs realised that it can be tricky “for an outsider to identify a community as the description of ‘where a community starts and ends’ depends on feedback from the community itself” [

25] (p. 8) quoting [

26] (p. 12). In fact, ‘communities’ are ‘messy’ and do not present themselves neatly to the external institution that wants to work with the people. Barrios highlights the difficulties in identifying communities as ‘clear entities’ [

27].

At least in policy documents, these approaches aim to build resilient ‘communities’ by the participation of local people, raising their awareness of disaster risk, taking into account existing local knowledge, as well as local capacities and institutions [

26,

28]. By claiming to deal with their vulnerability, and by recognising their right to participate in decisions that affect their lives, policy-makers and practitioners intend to improve the position of the most vulnerable and poor people and therefore enhance their active roles in shaping political processes [

29]. So much for the (good) intentions.

Some authors argue that DRR interventions are likely to be more successful if they remain within existing structures rather than create parallel or new ones [

30]. However, others claim that this will reproduce the underlying social structures and power relations and restrict the participation of poor and marginalised groups or individuals [

31,

32]. Jones et al. [

17] (p. 446) stress the point that insufficient concern is paid to “asymmetries of power and heterogeneity of interests in internally differentiated groups”. These may give rise to ‘elite capture’ [

33,

34]; local political, social or economic elites have the ability to form local associations through which they reinforce vested interests so that already powerful groups or individuals capture the development benefits [

35,

36]. As a consequence, socially embedded inequalities and vulnerabilities inherent to local power relations are reinforced.

Social capital (a highly contested concept in itself), as a function of the social cohesion of a group, has been highlighted as one of the most significant characteristics of resilient ‘communities’, insofar as it prejudices the extent to which a group is willing or able to work together towards a common aim [

15]. What makes a ‘community’ cohere has long been the subject of debate. It is argued that ‘community’ cohesion may derive from the extent to which the group is aware of a common threat which galvanises them to seek a common response. The term ‘community’ “never seems to be used unfavourably” because it is a “warmly persuasive word” that can refer to very different “set[s] of relationships” [

37] (p. 76), cited in [

38]; ‘community’ touches very deep human aspirations—it is an expression of the desire to experience a sense of belonging [

38].

3.1.1. The Challenge of Translating ‘Community’ into Action

Given the often-pragmatic approach of NGOs and agencies, what exactly is meant by working ‘with’ the people? How is ‘community’ framed by these organisations? And how to determine the boundaries between one ‘community’ and another, or a ‘community’ and outsiders? As the nature of interventions at the local level is shaped through the worldviews of the outside agencies and NGOs, there are many different ways in which they actually ‘do’ community-based work. For some, it means merely technical solutions at the local level, while for others it has the meaning and scope of a governance and human rights issue. Some consider ‘community-based’ DRR and CCA an approach to advance local level decision-making and partnering with local governments, while others interpret it as a matter-of-fact strategy to transform power relations and to challenge policies and ideologies that create local vulnerability [

29].

There are several examples of how development, DRR and CCA organisations deem the ‘community’ concept to be a potent vehicle to enhance the influence of local actors. The Red Cross, for instance, helped to reopen a hospital in Mogadishu in 2000 that had been standing idle for eight years. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the local ‘community’ was to be responsible for actually running the hospital. The administrators were to be appointed by ‘community’ leaders and to draw up the budget and conduct fundraising. ICRC, in its own words, was “merely one of the donors and advise[d] on training and budget planning” [

39]. By confiding trust in and responsibilities to local actors, the organisation actually reduces its own role to one of a donor or intermediary. This seems to be a common trait in translating the ‘community’ idea into action. The FAO, too, views its community-centred policy as one that supports “co-ordination among local institutions that can or should support food insecure groups” [

40] or enables “local communities [to] partner with governments to play a lead role in making land-use decisions and managing […] resources they depend on for their livelihoods” [

41].

This is a shift in roles away from the local people as passive beneficiaries to becoming actors who (allegedly) have a say in which direction a project should be heading, and who are involved in its implementation. For the organisation, this means replacing the planning and managing of every aspect of its intervention by becoming a ‘mere’ funder or mentor. Yet, for most organisations, there is usually no clear conception of what exactly the ‘community’ comprises. Is it ‘indigenous peoples’, ‘family smallholders’, ‘households’, ‘the village’? All these terms are often used as if they were interchangeable, and sometimes even in the same paragraph or sentence, as the example of a FAO news article on the organisation’s report on community-based forestry shows: “Indigenous peoples, local communities and family smallholders stand ready to maintain and restore forests, respond to climate change, conserve biodiversity and sustain livelihoods on a vast scale […]” [

41].

This ambiguity (which we will elaborate below) can seriously impair the success of DRR, CCA and development programmes. In response to a blog entry we posted to the Society for Conservation Biology’s Social Science Working Group (SSWG) listserv in 2016, we received numerous recounts by NGO personnel and researchers confirming the difficulties they encountered when working with vague community concepts. As Martina (name changed) replied:

“[…] because of the large scope of the projects, it was almost impossible to work closely enough with each community to truly understand their issues and dynamics throughout the programme. Eventually, one of the reasons I ended up leaving the organization was due to my concerns of the effectiveness of such ‘participatory and community-based’ exercises when having very little background knowledge of the particular communities and dynamics we were working with […]”.

(Martina 5 August 2016)

How did it get to this situation? Maskrey, in his publication “Disaster Mitigation: A Community-based Approach”, was one of the first to highlight grassroots efforts in reducing disaster risk from a local perspective [

42]. The pioneering NGOs that implemented projects at the ‘community’ level were not taken seriously at the beginning (in the 1980s). By contrast, he comments that in recent years community-based approaches “seem have to become mainstreamed to the point of orthodoxy” [

23] (p. 45).

3.1.2. The Rise of ‘Community’ in Development and DRR/CCA Action

Origins of ‘community-based’ development (and then DRR) lay in the critique of the top-down, single-event relief operations of governments and of top-down approaches in development planning. There was growing evidence that most hierarchical DRR and response programmes failed to address specific local needs, ignored the potential of local experiences, resources and capacities and in some cases may even have increased people’s vulnerability [

28]. The alternative ‘grassrooted’ approach began to take off in development activities in the 1980s, and was based on the need to enable local people (through ‘participation’) to have a much greater say in what form of ‘development’ happened to them. These approaches gained much of their popularity through the fairly wide-spread implementation of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) and similar ‘people first’-based approaches that aim to ‘empower’ individuals or groups, to enable local people to share, enhance and analyse their knowledge of life and conditions, and to plan and act—i.e., an information set that is not only elicited by outsiders but owned and operationalised by local people [

43]. The ‘Rural’ in PRA indicates the initial focus on rural poverty issues, although this was adapted to include a more generic Participatory Rapid Appraisal. The recognition of the need to include the so-called ‘target groups’ in identifying their ‘felt needs’ and drafting appropriate support measures was an outcome of the many failed development projects in the 1970s and early 1980s. Having been designed and implemented by outside experts, many of these were criticised for neither meeting people’s requirements nor showing long-term effects [

44,

45].

Local-level activities required the outside organisations to have a clear (geographical) boundary within which activities were to be carried out. In addition, because of a tendency to idealise local people as potential activists who would change their own destiny, it was easy to move into using the concept of ‘community’ as the default icon of this localised, participatory, ‘empowered’ local entity. In the 1990s and subsequently, all organisations wanting to conduct DRR at the local level developed very similar methods for intervening in the form of ‘community-based’ approaches that use vulnerability and capacity assessments based on PRA tools. These tools (such as VCA in the Red Cross movement, Participatory Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment (PVCA) in Christian Aid, and Participatory Vulnerability Analysis with ActionAid) are normally intended to both collect information to inform the intervention of the outside organisation, and to involve the local people (the ‘community’) in the process of change itself.

International organisations dealing with DRR became interested in the promising participatory approaches and readily assigned significance to ‘community’ and ‘community-based’ concepts. At the 1994 Yokohama meeting of the UN International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR), a greater focus on vulnerable communities was acknowledged as an international priority. Growing evidence in increased disaster occurrence and losses from small- and medium-scale disasters at a local level highlighted the need for proactive disaster management activities and the significant role of local residents (potentially) affected by hazards. In 2005, the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015 (HFA) and its successor, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030), prioritise(d) local DRR strategies and echoed the need to address disaster preparedness at the community level (using the concept rather than the local scale; [

46,

47]). The ‘community-based’ approaches laid down in these frameworks suppose harmonious interaction between governments at different levels and civil society actors. This approach, however, raises questions about mutual trust, the nature of participation of grassroots people, about representation and power dynamics.

The Yokohama Declaration 1994 reflected the growing influence of NGOs and a pro-localism culture, and “put an official seal of blessing on these approaches by stressing the importance of focusing disaster risk reduction efforts on poor communities” [

23] (p. 47). However, it must be said that the mainstreaming of ‘community-based’ approaches emphasised the role of NGOs as supporters of ‘community-focussed’ disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. Since then, ‘community-based’ approaches have been increasingly and enthusiastically taken up by almost all the major international NGOs and have been promoted by bilateral and multilateral organisations and governments and even by most ‘big players’ such as the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the IFRC. The concept of ‘community’ is now deeply embedded in DRR institutions, also ranging from local CBOs up to major international organisations that support it through their funding and rhetoric.

Along with the emerging paradigm of ‘community’ orientation in research, development work, DRR and CCA came the need to move away from an abstract collective social body on the one hand, and from a focus on individual persons on the other ([

48]; for an investigation of society-community-relations see Brint [

49]). ‘Community’ came in as an element of governance—some form of mediating instance linking individual subjects to policies and rendering these subjects manageable by assuming that individual ‘community’ members share values or interests and are mutually dependent: “Communities became zones to be investigated, mapped, classified, documented, interpreted […] to be taken into account in numberless encounters between professionals and their clients, whose individual conduct is now to be made intelligible in terms of the beliefs and values of ‘their community’.” [

50] (p. 89). Basically, the growing focus on ‘communities’ (rather than, e.g., on ‘citizens’) can be interpreted as a neoliberal way of transferring power into practices to manage ‘society’—a notion stemming from Foucault’s understandings of technologies of power and government [

51,

52,

53], [

48] (pp. 434–435). As a governance strategy, this then required a mobilisation of ‘communities’ in order to learn about their (allegedly) consensual needs and to let them have an influence on policy framing and implementation, now viewed as a shared endeavour of ‘community’ and professionals [

48] (p. 435).

‘Community’ mobilisation meant, and still means, a participatory process (initiated either on its own or by ‘outsiders’) through which “a community identifies and takes action on its shared concerns” [

54] (p. 262). This obviously implies that ‘community’ members collectively define their concerns and identify ways to address them [ibid]. However, despite the participation paradigm being widely advocated, the gap, as Chambers puts it, remains wide between fashionable rhetoric and field reality [

55]. Indeed, the shift to a bottom-up approach in the past 40 years or so (along with PRA methods and participatory assessments etc.) is a well-meaning effort to deliver real change to the most needy. However, there is rarely any reflection on what participation, ‘community’ or its adjunct ‘community-based’ actually mean. As we will show in detail below, the idea that a ‘community’ as a valid category for beneficial intervention schemes is deeply flawed.

3.2. Theorising ‘Community’: Interests, Norms, Identities, Belongings, Orderings

The rising popularity of ‘community’ described above has been based on a general framing that there are external actors and local people, and that a major challenge is to actively involve the latter in development schemes designed, or supported, by the former. Reducing the ‘community problem’ to a binary of insiders versus outsiders or locals versus experts would, however, not do full credit to what really is at stake. People’s behaviour in the face of threats or disasters is also embedded in what must be understood in its broadest sense as both ‘cultural’ and ‘situational’. Experience, attitudes, morale, values etc. will influence readiness to adopt, modify, or reject safety measures offered through outside assistance [

56,

57]. Situations which are beyond previous experience or expertise might demand new and creative solutions that are unknown to, or met with scepticism, suspicion, or rejection by, some actors involved. In light of this complexity, one might expect that in the academia and in DRR and CCA practice a first step would be to come up with a clear concept of ‘community’ before setting off to design, let alone implement, a research project or preparedness programme. As has been shown above, however, this is often not the case. Of the many handbooks, guidelines or project descriptions by major IGOs and NGOs we evaluated in search of their respective community definitions, only the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) comes up with a description that pays credit, unmistakably, to the social and situational fragmentations of communities, with a stress on unequal power relations:

“‘Community’ can be described as a group of people that recognizes itself or is recognized by outsiders as sharing common cultural, religious or other social features, backgrounds and interests, and that forms a collective identity with shared goals. However, what is externally perceived as a community might in fact be an entity with many sub-groups or communities. It might be divided into clans or castes or by social class, language or religion. A community might be inclusive and protective of its members; but it might also be socially controlling, making it difficult for sub-groups, particularly minorities and marginalized groups, to express their opinions and claim their rights”.

Apart from highlighting the internal divisions, the UNHCR manual also hints at the difficulties that might be encountered when working ‘in the field’: “Ideally, the community freely defines its priorities. But […] the goals of our agencies might not coincide with community practices or priorities” [

58] (p. 15). And still, this unusually frank description of the divisions and contradictions, and of the need to adopt an inclusive, rights-based approach that ensures “protection of

all members of the community” [

58] (p. 15), fails to deliver a comprehensive explanation of what is really meant by ‘community’.

Social scientists have actually never agreed on a definition of the concept of ‘community’ [

2] (p. 342). As it is an ambiguous concept, the understanding of what constitutes ‘community’ has become confused. The scientific ‘community’ (sic) is split into opponents and supporters of the concept. Even the author collective of this paper is not entirely agreed on a definition, and the severity of the falsehood, or the (potential) viability, of ‘community’. Opponents prefer to discard the term because it is not considered an appropriate analytical concept. Supporters aim at rehabilitating the concept due to its capacity to “express the emotional side of being together” [

59] (p. 212). A major critique presented by the notion of ‘community’ on a theoretical level consists in the fact that “‘community’ implies the assumption of an undifferentiated identity, and emphasises unity instead of diversity, spontaneity instead of mediation, emotions instead of reasoning, cohesion instead of conflict, and stability instead of change” [

59] (p. 212); see also [

57]. This, however, neglects the fact that ‘community’ conceptualisations have been far more multifaceted.

In academia, and especially in social and cultural studies, the conceptual debate has been evolving around two core elements that seem to be community-inherent and thus apt to constitute a group of people as a ‘community’:

Social relationships, connectiveness, interaction, affinity and cohesion that come along with various forms of dense acquaintanceship characterised by depth of knowing, shared memories and inter-generational attachments [

60], cited in [

1] (p. 183). In essence, this understanding links back to Ferdinand Tönnies’s seminal argument from 1887 which highlights a dichotomy of

Gemeinschaft (community) and

Gesellschaft (society) [

61,

62]. The mutual inter-connectedness of ‘community’ members would probably find its most basic form in “primordial type[s] of social organisation situated between family and kinship and society-at-large” [

1] (p. 182). Current interpretations of Tönnies’s classical take seek ways of updating the sense and definition of a community as type of ‘ready-made’ space for inclusion and exclusion [

62]. Tönnies’s logic of community is based on responsibility towards the ‘whole’ (the ‘collective’). Gafijczuk’s new interpretation includes the entwinement of modern individuals in each other’s fates, replacing responsibility at the traditional ‘community’ level by public responsiveness that defines mass society [

62]. ‘Community of Practice’ concepts, as tools to analyse links between the individual and the collective, situate organisational learning, knowledge transfer and participation as the central enterprise of collective action [

63] (p. 118).

Place, both as a defined territory that people share for living and continuous everyday doings (e.g., locality, proximity) and as a constructed, appropriated space infused or charged by meaning (e.g., inscription of narratives, attachment, propinquity beyond its merely physical dimension; cf. [

4]. This includes an understanding of ‘communities’ as a group of people who transform territory, and in doing so, configure locally specific patterns of vulnerability and generate a social territory of risk [

23] (p. 49).

While a combination of these two dimensions might be sufficient to differentiate one group of people from another through the social and spatial inter-connectedness of individual members, it says nothing about the hierarchies, disagreements or disputes within the group. Indeed, sharing knowledge and experiences or living together in a given locality is no valid indicator for harmony or equity. Different groups within a ‘community’ can have a memory of an event but have completely different experiences of it based on their class, ethnicity, gender, etc. In short, we must investigate a lot more deeply into the internal structures and processes of ‘community’.

3.2.1. The Internal Characteristics of ‘Community’

The framing of a ‘community’s’ internal structure has long been a key point in the social science debate [

1]. Brint, in his striking essay on community conceptualisations, reports on sociology studies from more than fifty years ago which emphasise “the structure of privilege as the hidden truth underlying nominally cohesive communities” [

49] (p. 6). These studies show that “the comforting image of community-centred governance was replaced by discovery of a self-interested and self-reproducing power structure from behind the scenes” [

49] (p. 6). Yet many scholars, and certainly most practitioners, are remarkably neglectful of these findings. In anthropology, the nature of ‘communities’ has also been extensively debated, mostly as geographically bounded social groupings. These are regarded as having a shared fate, but including relationships between people and institutions that extend beyond perceived boundaries in space and time. This highlights the difficulties in identifying ‘communities’ as ‘clear entities’ [

27].

However, ‘community’ is not only designated by a group of interacting people sharing the same place and similar understandings, values, or life practices. As Oliver-Smith [

64] (p. 54) and Cohen [

65] point out, it is a cultural field with a complex of symbols and, as such, possesses an identity and is capable of acting on its behalf or on behalf of those who have a claim on that identity. In that sense, community is not a container whose size and contents can be easily measured. Quite obviously it “does not connote homogeneity and certainly does not admit differences within and among communities. More than anything else, community is an outcome, a result of a shared past of varying lengths” [

64] (p. 54). In addition, contrary to other positions in the debate, Oliver-Smith notes that “[n]ormally, communities do not construct themselves—they evolve.” [

64] (p. 55). This becomes particularly evident with people who have been displaced as a result of a disaster. These resettled persons often have difficulties in drawing on the cultural resources that used to constitute part of their ‘community’ because those resources cannot be transported to somewhere else as if shipped in a freight container.

It follows that value consensus is probably not a ubiquitous feature of ‘community’ [

1] (p. 184). In their study on development projects and climate change adaptation on Pele Island, Vanuatu, Buggy and McNamara found several community-related issues that contributed to the majority of over 30 projects breaking down, stalling or being abandoned [

66]. Key challenges relating to the underlying social context within the community included lack of support and respect for established projects as well as disagreements and disputes [

66] (p. 274). Issues of power and leadership created an environment that enabled particular groups and individuals to dominate projects, restricting fully fledged participation of other community members [

66] (p. 275). In his structural model of community, Barrett attempts to offer a way of assessing egalitarian relationships and inequality, solidarity and exclusion, and inter-relations between internal processes and the wider dynamics of vulnerability and resilience [

1]. He argues that the three dimensions ‘interests’, ‘normativity’ and ‘identity’ form the structural DNA of community, and goes on to note that “the degree of nesting of the individual within the collective level is a key factor in comparative community differentiation and features prominently in the impact of social change and the prospects for community resilience.” [

1] (p. 185). Private (individual) interests (such as livelihood pursuits, wealth and property relations) can largely be associated with exclusionary tendencies. However, collective interests can be manifested in an array of social goods and institutions such as reciprocity and sharing, common property or co-operative labour. These contribute to solidarity and sometimes serve to check antagonistic private interests. Barrett’s model reaches beyond conventional binary approaches by including, for instance, exploitative relationships where private interests are organised along class or caste lines and the wealth and power of one group is used to systematically control, or oppress, another.

It is here where the second dimension, normativity, comes into play. Normativity refers to a codified set of standards of conduct and rules which are embodied in symbols and structure everyday social control. These prescribe and facilitate certain forms of interaction and offer orientation. Barrett provides a striking example of how norms add to the stabilisation of ‘community’ despite the strong presence of individual interests [

1]; in hierarchical communities, norms of deference and superiority may legitimate exploitative property and power relations because they are closely tied to clientelism. These vertical norms are cross-class—despite serving the individual interests of those in power, they have the effect of stabilising exploitative environments, thereby achieving what can be called an endogenous structured coherence at the ‘local’ level [

1] (p. 189). However, by structuring and perpetuating relations, the normative force does not necessarily take a disciplinary form [

67]. A common set of regulatory norms, informal or formal, which is transformed into a technology (as ‘a way of knowing and doing things’) can accelerate and intensify agency in particular directions, at least for those who have gained an insight into, and are taking advantage of, the potentials and specifics of that technology [

67] (p. 241). However, norms do not simply reproduce interests [

1] (p. 190). They can bridge differences between individual interests, but they also cover hidden conflicts; conformity to norms should not be confused with their acceptance. Normative compliance is not necessarily a matter of consensus. It is often rooted in obligations or fear of exclusion.

As outlined earlier, identity has often been interpreted as ‘the’ core element of ‘community’ (cf. [

64]). Manifestations of collective identity are embodied in common symbols, traditions, customs or rituals whose meanings are understood by ‘insiders’ and stem from shared history and experiences. In his inspiring model, Barrett links identity to interests and norms [

1]; traditions or rituals which are symbolically expressed, for example through festivals, may generate private benefits (for instance as sources of prestige) as well as mobilising social capital (e.g., through the redistribution of wealth) or stimulate communal reassurance. The dominant source of collective identity is often, but not always place-based, as it “incorporates a sense of heritage manifest in long-standing traditions” [

1] (p. 192). This might explain why identity and place are so often mentioned as defining elements of ‘community’ in organisations’ guidelines or project reports. Place (often simply referred to as ‘local’) can be easily identified by geographic coordinates or the name of a village, while identity—a lot more complicated to pin down—is then simply defined by what the people living there (allegedly) have in common (a consensual set of values). Of course, this neither pays credit to the complexity of places and spaces nor does it take interests, norms and the multiplicity of identity into account. When it comes to places and ‘the local’, Devine-Wright has aptly highlighted the intricacies of attempts to identify local identities and attachments [

68]. Narratives of community solidarity and place protection are frequently employed to resist (or support) imposed developments [

68] (p. 527), but one may add that it is extremely difficult to separate such strategies from underlying perceptions of place which are deeply embedded in identities.

3.2.2. Beyond the Place–Identity Binary

Bridging the place-identity binary, the concept of ‘belonging’ has been mobilised recently to describe forms of place attachment as well as constructions of particular collectivities [

69]. If interpreted as a geographical concept, belonging relates people with their social and material worlds and is produced through interactions of place and feelings [

69] (p. 395); [

70,

71]. Add to this notions of inclusiveness, cohesion or connectedness (or their respective antonyms), and the conceptual vicinity of community becomes obvious. Being a “deep emotional need of people” [

72] (p. 215) cited in [

69], belonging reaches beyond identity but includes the latter’s notions of connectivity, empathy and attachment. It shifts the focus to intrinsic practices that make sense of people living-with-each-other and thus help to reproduce community.

In a similar vein, the German concept of

Heimat signifies more than its common English translation as ‘home’: it actually merges place and belonging. Weichhart explains how

Heimat, one’s home territory, emerges as both an emotional ascription and functional practice [

73]: it is the place where one’s ways of acting and transacting are concentrated and where one is most likely to experience a confirmation of and reassurance about one’s own doings and thinking. In short, home territories are places where one’s self-identity can be stabilised most efficiently and profoundly [

73] (p. 294; loosely translated). Again, the link to community is fairly obvious:

Heimat reproduces community as a group of people sharing this notion of home territory and experiencing a collective place-bound reassurance of their ways of acting. As with

Heimat, this collective and spatially ascribed reassurance of oneself is not static; home territories can be fluid, they exist wherever the collective can best produce and reproduce reassurance, identity and belonging.

Brint, in his community typology, differentiates between two major sub-types [

49]: geographic and choice-based communities. Brint then looks at the primary motivation for interaction between community members and divides both sub-types into activity-based and belief-based reasons to interact. Adding yet another level of sub-branches, Brint divides geographic communities according to the frequency of interaction, and choice-based communities according to the location of their members and the amount and intensity of their face-to-face communication [

49] (pp. 10–11). The partitions help “to identify latent structural variables that generate key differences in the organization and climate of community types” [

49] (p. 11). This is, indeed, an important step in understanding why, and how, one community is different from another, in which ways individual members are embedded in, or detached from, interactions within their group, or how much pressure is generally exerted on members to conform to prescribed norms and values. However, one could argue that all sub-types bring with them ‘belonging’ as described above, irrespective of the shape and function of a particular community. ‘Belonging’ escapes a clear measurement of intensity and emotionality. Brint’s typology, while valuable for a better understanding of the structural intricacies of differing communities, fails to capture this important feature of community reproduction.

Of course, none of the dimensions (or sub-types) of ‘community’ are static. They are depending on situations and change over time. There has been much debate on the effects of modernisation, globalisation or climate change on the nature and extent of collective perceptions and action (e.g., [

66], to name but one of many case studies). Indeed, the fashionable term community-based

adaptation in itself implies a constant transition of community-related practices as the need to adapt only arises when situations or conditions change. In light of an increasing pace and scope of contestations and lifestyle choices, questions have been raised whether modernity has uncoupled identity from its connection to norms and interests [

1] (p. 193). This has made it even more difficult to uncover the “hidden features of the solidarity-exclusion dialectic” [

1] (p. 194). Identifying and exploring these hidden features is a major challenge, but also a prerequisite for any serious ‘community’-related research or action.

3.2.3. ‘Community’, Culture, and Orderings

Given the multiplicity of ‘community’ dimensions, it is quite obvious that ‘community’, at least in its classic conceptualisations which ultimately stem from Tönnies’s work [

61] outlined above, is deeply rooted in culture. This, however, only makes matters worse when trying to theorise ‘community’. In an attempt to highlight how risk and disasters are inseparable from culture, the latter was approached, in pragmatic fashion, as “beliefs, attitudes, feelings, experiences, values and narratives, and their associated behaviours, actions and day-to-day routines that are shared by, or at least abided by, most people in respect to threats and hazards” [

74] (p. 5). This draws on the function of culture as the provider of the ways that people interpret, assess and adapt with their peers and other members of society to the risk environment in which they live. One element of ordering this risk environment is organising oneself as a ‘community’, quite in line with what we explained above as technologies of government and governance [

48,

50]. ‘Community’, if accepted as a valid concept that describes people’s connectiveness and cohesion, provides members with shared codes, representations, and norms, and fulfils members’ practical needs in serving as an (often) well-organised structure to which they can turn for dealing with both ordinary and extraordinary tasks [

59] (p. 223). In short, ‘community’, as a cultural technology and as institutionalised practices, is inserted in quotidian discourses, routines and actions and provides certainties and predictabilities in order to reduce contingencies in everyday life.

Any ordering technology can fail, and so can ‘community’. Disasters, e.g., can trigger singular situations where common assumptions break down, institutionalised practices are contested and corrupted, and some of the actors involved come up with unconventional suggestions, exceptional solutions and creative responses [

74] (p. 6). As catalysts for cultural change, disasters have long been transformative agents in their own right, causing political, economic and social adjustments or even thorough ruptures, upsets, breakdowns and complete societal as well as material rebuilds. However, although a disaster is devastating in many respects, there are instances where more robust, efficient and fair institutions may emerge in its aftermath. In a striking example of how disasters effect governance patterns, Aoki has shown how the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and the resulting tsunami have turned the small town of Onagawa, devastatingly hit by the flood wave, into a role model of progressive democratic change [

75]. In particular, the surviving members of the town’s commercial and industry association established a reconstruction council after the disaster event. Aoki highlights that, at the inception of this council, members of the younger generation were asked to assume leadership—a procedure that would have been unheard of in the pre-disaster, ‘conservative’ local socio-political order [

75]. This establishment of a new, participatory (and, as it turned out, successful) governance scheme which was based on a much more egalitarian notion of community is a clear hint at fundamental institutional transformations incurred in the wake of disasters.

We believe that our argument has, over the past pages, made it quite clear that bringing order into everyday life, providing certainties and meaning, and thus helping people to adequately handling challenges ‘in their own ways’ are elements inherent in ‘community’ that hold the most important (potential) added values for ‘community’ members. As Solesbury points out, community implies “a commonality of values, identities and interests that help people to live together” [

76] (p. 140). However, Solesbury, drawing on ‘the city as community’ as a common metaphor, also highlights a very important shift of meaning: “But, shift to the plural—communities—and differences on the basis of location, class, income, sexuality, ethnicity or faith are immediately implicit” [

76] (p. 140). The city (and, we may add, any other spatial or social entity associated with ‘community’) now becomes a place where values and interests are in contest—in short, it is turning into a battleground. In its extreme forms, ‘communities’ (

pl.) and the conflicts between them become embodied in the structure of the city (or any other body) such that “the necessities for living together—security, health, shelter, neighbourliness—are no longer there” [

76] (p. 140; Aleppo, Mogadishu and other places in war or crisis zones as examples). In another example, Bartels, based on the idea of ‘quiet encroachment’ by Bayat [

77], explains how members of the middle-class are, in semi-legal fashion, quietly encroaching the peri-urban areas of Accra (Ghana) by informally, and individually, constructing new houses there [

78]. This practice is now increasingly challenged both by marginalised, poorer people and by the municipal authorities. It becomes a political, and as such a collective, act. What used to be individual decisions and doings now turn into a community practice opposed by other communities. The battleground, in Solesbury’s words, is open.

These examples show that it remains to be answered whether ‘community’ is needed at all to understand what are in essence conflicts over resources, control and domination. Opponents of the concept stress the small explanatory value of the ‘community’ idea. They therefore feel uneasy with employing the concept when analysing the ‘battlegrounds’ and either discard the term entirely (on the grounds of there being sufficient other terms like ‘people’ or ‘residents’) or introduce alternative terms deemed more precise. One such concept in the urban environment is ‘neighbourhood’. It has the potential to avoid the problematic notion of commonality associated with ‘community’ and stresses activism as a response to threats or resource opportunities [

79]. The problem with ‘neighbourhood’ and many other alternatives is that they will most likely have already been introduced in other realms of research or action and thus carry specific connotations, or they are equally ambiguous or confusing and thus not a useful replacement.

These observations do have huge implications in the analysis of ‘community/communities’ and in everyday development or relief work. Not only must we realise that ‘community’ is often not a given, holistic, and harmonious social body or institution. We must also make it quite clear which ‘community’ we are actually talking about when doing research or (development or DRR) action as there is usually not only one but many ‘communities’, often competing or even fighting each other. ‘Community’ becomes ultimately problematic if imposed from outside on a group of people; it is meaningless at best and harmful at worst, as it disguises and neglects internal hierarchies, frictions and conflicts and is rather for the ‘outsiders’’ convenience than serving the interests of the group members. Relating to ‘the neighbourhood, ‘the village’, ‘the urban poor’, ‘the landless’ and infinite other groupings as ‘community’ may well express what we intend to say or do—working at the ‘grassroots level’ and ‘with the people’—but beyond that, it has little analytical or explanatory power if we are not more precise about whom we actually attempt to target.

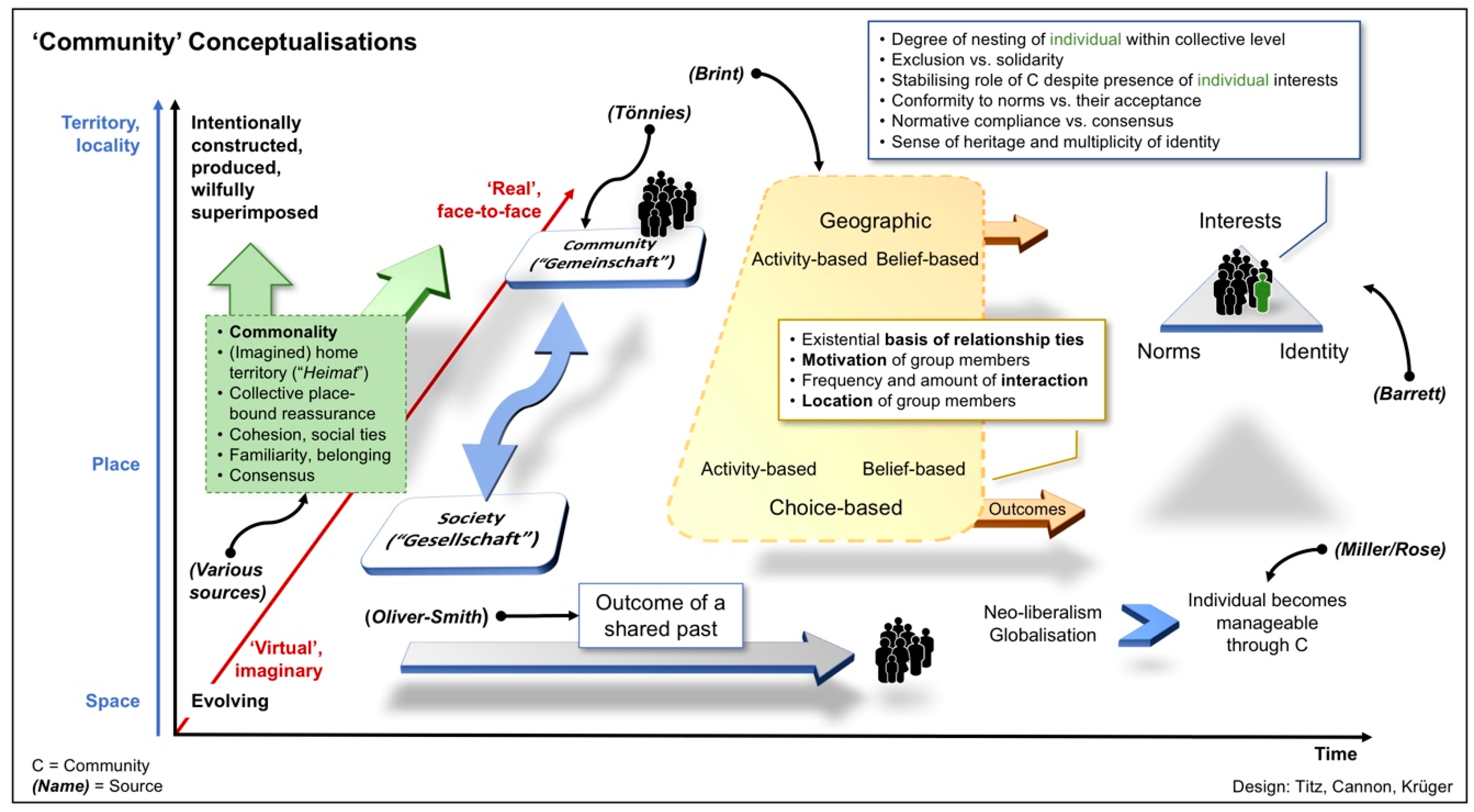

The following figure illustrates the many dimensions of ‘community’ that have been highlighted in theories and analytical conceptualisations outlined above (

Figure 1). For the illustration, we selected five approaches which, in our view, best represent the different conceptualisations of ‘community’ that have emerged over many decades. To those, we added cross-cutting terms and themes that have become popular with most if not all ‘community’-related definitions and concepts (green box). The selected conceptualisations are structured three-dimensionally along three axes: the x-axis ‘time’ depicts the process-related, dynamic aspect of ‘community’ and its formation. It is not meant to place the conceptualisations themselves in a particular order of appearance; ‘time’ simply signifies how ‘community’ and its outcomes change over time. The y-axis is twofold and relates (a) to an increasingly concrete form of space that (co-)defines ‘community’ (via place to a specific location or demarcated territory which can also be highly emotionally charged, i.e., inscribed with meaning); and (b) to a transition from evolving to deliberately produced ‘communities’ and their configurations. The z-axis leads from ‘virtual’, imaginary ‘communities’ to groupings that are marked by ‘real’, direct face-to-face contact between members. The figure is not intended to cover all ‘community’ notions in their entirety nor is it meant to be a finite graphic concept. Its purpose is instead to pull together and structure the vast scope of different ‘community’ framings that have been developed over the past decades. Its message is simple: ‘community’ is a complicated and contested matter. We hope to convey to academia and ‘practitioners’ an understanding of why ‘community-based’ work is so often failing: it is almost impossible to agree on a least common denominator of what ‘community’ means.

4. Discussion

4.1. The (Im)Possibility of Working “Community-Based”

4.1.1. ‘Community’—An Appealing Idea

Solesbury’s battleground [

76], one might argue, tarnishes the image of ‘community/ies’ as a desirable and comforting social organisation or technology that we want to investigate or do development or DRR work with. However, why is the cuddly notion of ‘community’ so enduring? Brint’s typology, outlined above, might provide an answer: He asks about the “[…] reasons why the idea of community as symbol and aspiration of a more egalitarian and accepting order persists even in the face of a long tradition of contrary findings in community and small-group studies” [

49] (p. 20). The idea is so enduring because, in certain types of ‘community’, hierarchies, frictions and struggles remain invisible (or largely irrelevant). This happens in ‘communities’ characterised by few face-to-face relations between their members: “A realm of autonomous equals bound to a framework of common moral norms is possible only in a world in which members are rarely, if ever, copresent. […] Only imaginary communities can appeal to the wish for an egalitarian world in which everyone is validated and in which all contribute as one […].” [

49] (p. 20). In other words, the idea of a ‘harmonious together’ is advocated (and probably believed and lived) by concrete people who are, themselves, members of belief-based but spatially dispersed ‘communities’. Most humanitarian organisations, for instance, will at least partly fall into that category—‘communities’ that, by virtue of their predispositions or because of the very nature of their belief-based philanthropic and charitable claims, are forever reproducing a mythical image of social equity and equality.

What did we learn from the pathways the ‘community’ idea has moved along, and from the theoretical frameworks of ‘community’ we outlined above? First and foremost: ‘community’ is complex, and therefore, probably too difficult and complicated to serve as a viable scheme for development and DRR/CCA related work. However, on the other hand, it is so appealing! ‘Community’ is about people. It has a bottom-up, ‘with-the-people’ and ‘for-the-people’ notion and is therefore readily embraced by many development and DRR/CCA organisations.

Our argument here is, therefore, not to deny the way that ‘community’ can appear to outsiders as a meaningful concept. We have talked above about the persistence of the ‘community’ idea, and there are without any doubt a huge number of ways that people live in what appear to be ‘communities’. This is especially evident in the rural context, and especially in the Global South (where most DRR and CCA interventions take place). Urban definitions of ‘community’ are probably more complex and difficult in many ways precisely because there is sometimes no sense of a co-placed set of livelihoods in which there are mutual dependencies between people who are known to each other. However, above we have also drawn some arguments from the metaphor of the city as community (as has been explored by Solesbury [

76] or Blokland who sees “community as urban practice” [

80]), and we are currently undertaking research on concepts of Just Cities and Right to City and justice frameworks to examine how the concept of ‘community’ can be assessed in urban contexts [

81].

Most evidently, the local rural economy is based on the use of land and related resources for a set of livelihoods that are relatively well-integrated, in which the main livelihood activities are related to that place. Historically then, people have emerged socially as place-sharing systems, in which there is a locality-based functionality. Related to this, very strong emotional and symbolic awareness of that place seems to develop in many parts of the world. People have their own sense of meaning—their ‘lived experience’—that literally places them in that territory and locality as a way that gives meaning to their lives. This can even apply to the poorest and most vulnerable, who may share their sense of place attachment despite the dangers (natural hazards, etc.) that afflict them there. As outlined in detail in the previous chapters, place attachment can be a powerful means by which people create an identity. In addition, beyond the spatial dimension, ‘community’ as “a result of a shared past” [

64] (p. 54)—albeit one that may be memorised and interpreted very differently by each individual in the collective—or as a social concept providing collective reassurance is, undeniably, an essential and meaningful cultural technology.

The spatial dimension of ‘community’ is appealing to development and humanitarian organisations because it is through ‘location’ that the people whom one wants to work with can best be identified and approached. In DRR and CCA practice, there is often only little awareness of the intense debates outlined above about the notions of ‘community’ in sociology, anthropology and development studies that have been going on for decades. What ‘community’ or ‘community-based’ actually means is rarely discussed in policy-papers, reports and practitioners’ handbooks on DRR and CCA activities. A certain fixation on space is also a welcome strategy in DRR and CCA practice because it seemingly provides some form of calculability in one’s work in times of rapid global change. In this context, Wiseman argues that many of the claims about strengthening social cohesion and increasing participation are exaggerated, since local strategies are no substitute for the progressive policies that are required to create an environment for comprehensive and sustainable reductions in power-inequality, poverty, and social exclusion [

82]. In social sciences, much of the current debate about ‘community’ is concerned with whether or not the term can be meaningful in the age of individualisation and globalisation. Society and economy are now less organised around local relations, identities are increasingly formed through engagement in virtual communities, civic togetherness in terms of everyday ‘community-based’ practices and traditional forms of ‘community’ beyond the family are beginning to disappear [

83]. While ‘community’ (re)studies in the social sciences are used to illuminate processes of social change as well as to track changing social divisions and inequalities, this potential is being ignored by many organisations and NGOs. Questions might be raised about the extent to which the idea of ‘community’ is still viable as a way of DDR intervention and CCA activities.

4.1.2. ‘Community’ as a Strategic Framing

As Heijmans points out, there are many distortions when practised ‘local’ tradition interacts with those promoted by international, non-place-based actors [

29]. Humanitarian agencies and development organisations often act as if they shared a common language and definitions, but they attach very different meanings to the reason what they call ‘communities’ are vulnerable. They therefore believe in different strategies and goals (espoused theory: what is written in policy-documents; versus theory-in-use: defines what people actually do). Organisations use ‘frames’ strategically to deal with actors who do not necessarily share the same values or views, but with whom it is crucial to maintain relationships. Organisations seem to strategically manoeuvre between multiple realities to maintain such relationships; they continuously frame and re-frame narratives to adapt to changing realities. NGO staff, for example, use multiple ‘frames’ and specific ‘languages’ to find legitimation to survive. When writing proposals to donor agencies, language from disaster management literature is used to access funds [

29]. In fact, organisations and agencies thus tend to reduce complexity of bottom-up, ‘community-based’ concepts (by, e.g., focusing on location) but, on the other hand, keep on re-framing community narratives as a tool to legitimatise their purposes and doings. This is treading soft ground, and NGO personnel, as well as researchers, often struggle in their attempts to navigate between the various layers of community framings. In response to our SSWG listserv entry in 2016, Susan (name changed) who has been working in the public health sector and on the impact of pandemics wrote:

“I am […] extremely sensitive (and critical) of the flippancy with which the term ‘community’ is used […]. At the same time, I consider myself someone who does ‘community-based’ research, and try so hard to balance awareness and sensitivity to contours of power and access with demands/expectations of funders/collaborators. One field site I’ve been involved in for 10 years, and have a pretty good sense of the many, many layers of culture and society that I am excluded from. […] It’s coming together in pieces now, in the form of community staff taking on priorities that they’ve identified (who knows how well that actually represents communal priorities) but the outward face of this work pretty much follows the traditional global health narrative.”

(Susan, 4 May 2016)

Indeed, in DRR and CCA, simplistic conceptions of ‘community’ should rather be abandoned in order to think of them as “fragmented, hybrid, multiple, overlapping and activated differently in different arenas and practices” [

84] (p. 178) cited in [

2]. However, agencies and NGOs often take ‘community’ as a given and assume that it can be mobilised relatively easily in order to adapt disaster risk reduction practices or foster climate change adaption. In this context, Bulley argues that communities need to be ‘produced’ before they can be mobilised [

85] (p. 276). In addition, as Delanty points out, community has become something that needs to be “wilfully constructed” and constantly recreated [

86] (p. 102). This is in contrast to other conceptions outlined above that view ‘communities’ as evolving rather than intentionally produced (e.g., [

64]), albeit probably not by mere chance (cf.

Figure 1). This discordance makes it even more challenging to be clear about the notion of ‘community’ one is working with.

Community framings are, thus, strategic undertakings to acquire support and funds, design and implement intervention measures without too many disturbances and distortions, and gain publicity for their cause. This is understandable, as donors must see their ‘investments’ being put to good (and speedy) use, and humanitarian and development agencies and organisations have to get on with their well-intentioned work. There is often no time, sometimes no money, and occasionally no will to ponder on complexities. ‘Community-based’ work must produce visible action and deliver traceable outcomes. As Lillian (name changed), having worked in the natural resource management sector in Southeast Asia for several years, replied to our SSWG blog entry:

“People do tend to see ‘communities’ and ‘grassroots movements’ as monoliths, which they are not. […] [I] have experienced a lot of instances where well-intentioned activists and donors are intervening in a power struggle between the government and a ‘community network.’ After all this assistance, the network has now splintered into multiple factions who are each accusing the other of having become corrupted and joint in with illegal logging/abusing government connections etc. […] It’s pretty clear to me that a lot of the outsiders’ well-meaning work (and of course they have their own political and personal agendas, e.g., supporting the opposition movement or making headlines for the cause) has shifted the dynamic and exacerbated some of the problems.”

(Lillian, 14 May 2016)

These observations do not fit the strategic framings. The latent ambiguity and dialectic, i.e., solidarity versus exclusion, or rather individual liberty versus collective solidarity, that characterises many of the community types outlined earlier in this paper, is hard to deal with in everyday humanitarian action, especially in the fields of DRR and CCA. The idea that members of a ‘community’ are characterised by the fact that they have something in common also serves to distinguish them from ‘others’ who are not part of the ‘community’ (‘othering’). The othering that comes along with ‘community’ formation (as well as with strategic framings) implies processes of physical, social and/or conceptual boundary setting and exclusion. These boundaries “divide and exclude as much as they enclose and include” and “enclose difference or diversity as much as sameness” [

2] (p. 344). In addition, it often remains unclear to outsiders who has the authority to define who is, or may become, a member of a given ‘community’ and who will be left out.

The idea of ‘social capital’ features strongly in those framings. Fostering social capital is frequently seen as an appropriate tool to overcome exclusion and divisions. This begs two questions: who is the agent that is ‘doing’ the fostering? And who are the addressees or recipients, given the diversity of sub-groups and interests within the so-called ‘community’? Still, stressing social capital as an inherent element of ‘community’ has been a widespread strategy of external agencies and organisations for decades. However, little attention has been paid to the complex issue of the downside of social capital. When ‘handing over’ an externally induced ‘community-based’ project to ‘the locals’, elite capture during the transition phase from external to internal management is not uncommon but it is rarely acknowledged as a problem [

87] (p. 184). In some instances, power relationships have indeed been taken seriously in the institutional design of ‘community-based’ projects. Wong describes two cases, a solar home system in Bangladesh representing a ‘counter-elite’ approach which explicitly excludes local elites from the decision-making process, and a trans-boundary water governance project in Ghana which adopts a ‘co-opt-elite’ approach and deliberately absorbs local elites into the decision-making committee [

34]. The study demonstrates “the paradoxes of including and excluding local elites in the community-based development. The dilemmas are that challenging the authority of local elites, by excluding them from the governance structures, does not necessarily undermine their influence, whereas co-opting with them in the new institutional arrangements risks reinforcing power inequalities and worsening poverty” [

34] (pp. 14–15). However, the study also shows that actively embracing the problem of elite capture has more merits than ignoring or circumventing it. Elites can be absorbed and challenged in the same project at the same time [

34] (p. 15), employing a flexible use of the ‘counter-elite’ and ‘co-opt-elite’ approaches together with seeking alternative livelihoods and empowerment solutions for the vulnerable.

More often than not, however, implementing agencies and NGOs are apparently either not aware of already existing institutions, organisations, orders, and arrangements at the local level, and of internal fractions and power structures, or these are intentionally not taken into account in favour of a smooth realisation or fading-out of their projects. Formations imposed from outside may thus be transverse, or contrary, to existing internal formations. In one of many examples, Adhikary and Goldey, based on empirical research on ‘community-based’ organisations in over a dozen villages in Nepal, show how the strong emotional power inherent in the concept of ‘community’ can also make it a dangerous idea [

87]: while, theoretically, uniting people in a group and carrying out activities involves trust and the norms and behaviours of cooperation [