Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Socioeconomic Differences in the Support for Redistributive Policies

2.2. Cross-National Differences in the Support for Redistributive Policies

2.3. Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? Redistributive Preferences by the Working Poor

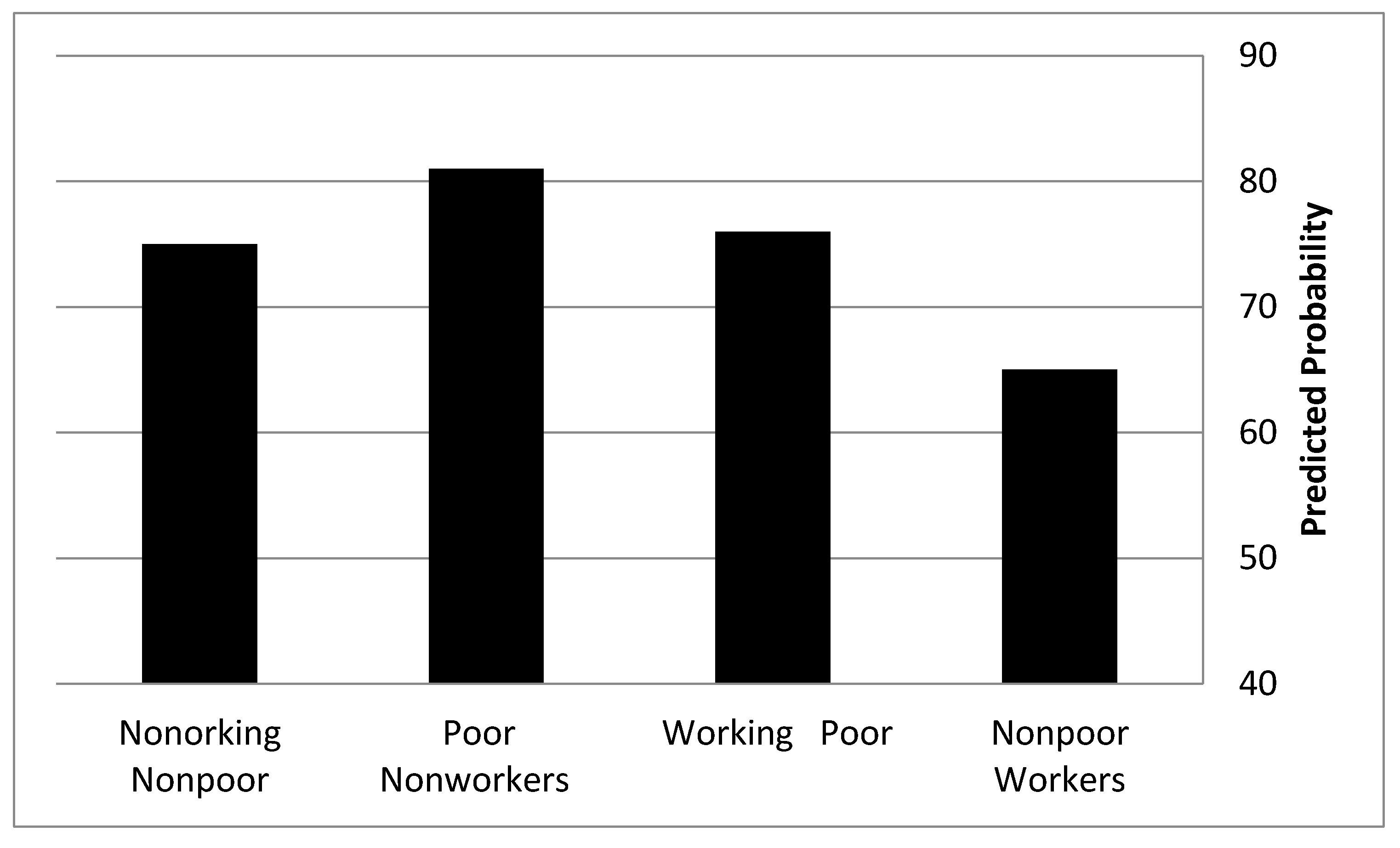

- Do the working poor express greater support for redistribution than non-poor workers?

- Do the working poor express a weaker support for redistribution than non-working poor individuals?

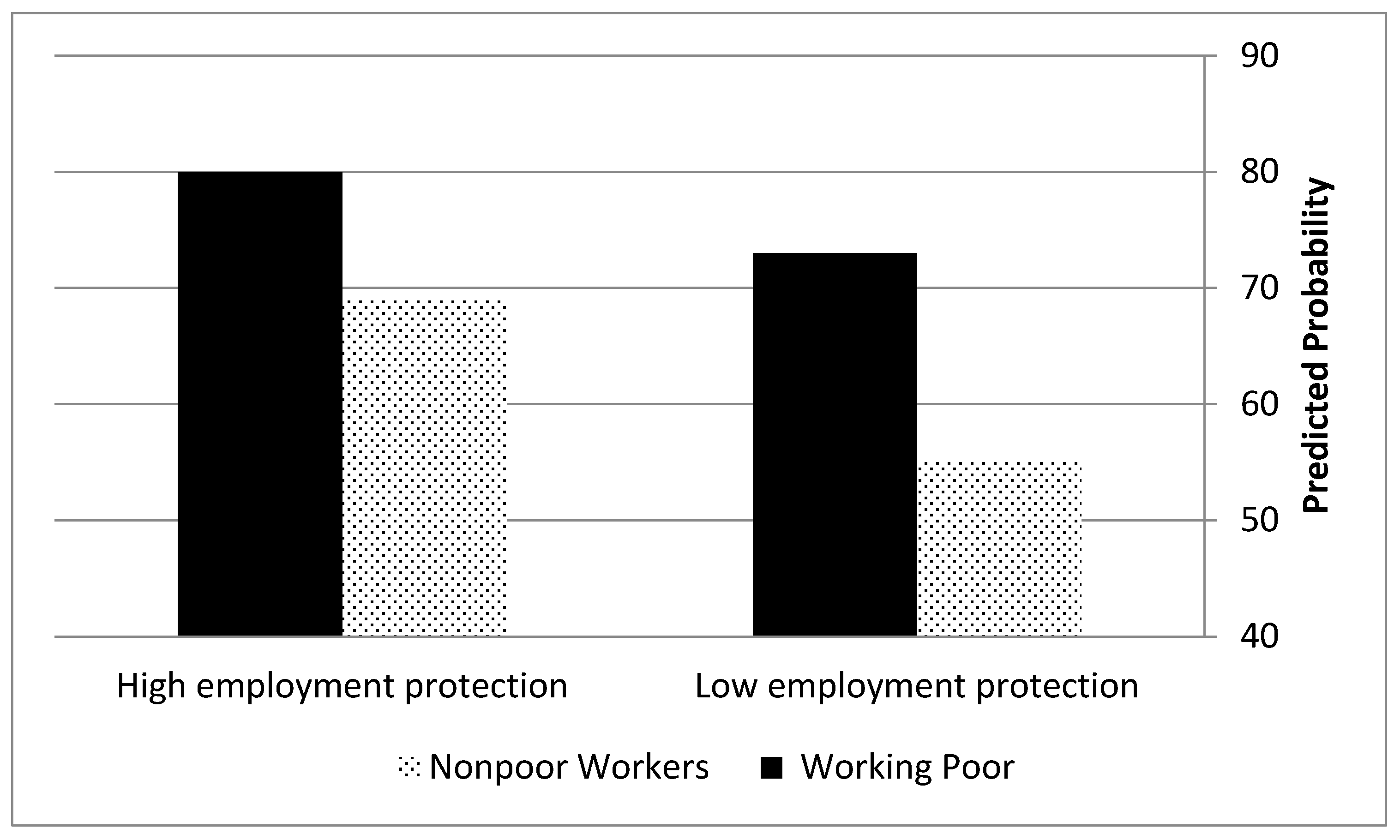

- Is the gap between the working poor and non-poor workers weaker in countries providing stricter employment protection?

- Is the gap between the working poor and non-working poor individuals weaker in countries with higher expenditures on employment training and unemployment benefits?

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

- (1)

- The ISSP (international social survey program), which is conducted every year in numerous countries—each year on a different issue. We chose all the modules conducted on the issue of the role of government (years 1985, 1990, 1996 and 2006), and on the issue of social inequality (years 1987, 1992, 1999 and 2009). Especially for the role of government modules, the purpose of these surveys was to examine the respondents’ attitudes towards government responsibility and the level of proper intervention in social and economic issues.

- (2)

- The ESS (European social survey), which was conducted in the years 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010. Unlike the ISSP, this survey is conducted only in European countries, but it too examines the respondents’ attitudes towards various civil, economic and political issues.

3.2. Variables

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

5. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breen, R. Risk, Recommodification and Stratification. Sociology 1997, 31, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, M.; Brooks, C.; Manza, J. The democratic class struggle in the United States, 1948–1992. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipset, S.M. Political Man; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy; International Library Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, L.; Manza, J. Class differences in social and political attitudes in the United States. In The Oxford Handbook of American Public Opinion and the Media; Shapiro, R.Y., Jacobs, L.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 552–570. [Google Scholar]

- Offe, C. Democracy against the Welfare State? Structural Foundations of Neoconservative Political Opportunities. Political Theory 1987, 15, 501–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, J.; Iversen, T. Inequality, labor market segmentation, and preferences for redistribution. Am. J. Political Sci. 2017, 61, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreß, H.J.; Heien, T. Four worlds of welfare state attitudes? A comparison of Germany, Norway, and the United States. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 17, 337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune, M. Economic conditions and public attitudes to welfare policies. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anjou, L.; Steijn, A.; Van Aarsen, D. Social position, ideology, and distributive justice. Soc. Justice Res. 1995, 8, 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, J. Trust in government and welfare regimes: Attitudes to redistribution and financial cheating in the USA and Norway. Eur. J. Political Res. 1999, 35, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenfeld Edlund, Y.; Rafferty, J.A. The determinants of public attitudes toward the welfare state. Soc. Forces 1989, 67, 1027–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, M.M. Welfare regimes and attitudes towards redistribution: The regime hypothesis revisited. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 22, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluegal, J.R.; Smith, E.R. Beliefs about Inequality; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-Epstein, N.; Kaplan, A.; Levanon, A. Distributive justice and attitudes toward the welfare state. Soc. Justice Res. 2003, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosimann, N.; Pontusson, J. Solidaristic unionism and support for redistribution in contemporary Europe. World Politics 2017, 69, 448–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, L.A.; Pedulla, D.S. Material Welfare and Changing Political Preferences: The Case of Support for Redistributive Social Policies. Soc. Forces 2014, 92, 1087–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, D. Food Comes First, Then Morals: Redistribution Preferences, Parochial Altruism, and Immigration in Western Europe. J. Politics 2018, 80, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svallfors, S. Worlds of welfare and attitudes to redistribution: A comparison of eight western nations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 13, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.H.E. Patience moderates the class cleavage in demand for redistribution. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 70, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, C.; Papadakis, E. A comparison of mass attitudes towards the welfare state in different institutional regimes, 1985–1990. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 1998, 10, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekesaune, M.M.; Quadagno, J. Public attitudes toward welfare state policies a comparative analysis of 24 nations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 19, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelissen, J. Popular support for institutionalised solidarity: A comparison between European welfare states. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2000, 9, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linos, K.; West, M. Self-interest, Social Beliefs, and Attitudes to Redistribution. Re-addressing the Issue of Cross-national Variation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 19, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svallfors, S. Class, attitudes and the welfare state: Sweden in comparative perspective. Soc. Policy Adm. 2004, 38, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economics; University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Is Work the Best Antidote to Poverty? In OECD Employment Outlook: Tackling the Jobs Crisis; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 165–210. [Google Scholar]

- Shipler, D.K. The Working Poor: Invisible in America; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stier, H.; Lewin, A. Does women’s employment reduce poverty? Evidence from Israel. Work. Empl. Soc. 2002, 16, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.J. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi, D. Differences that Matter: Social Policy and the Working Poor in the United States and Canada; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, D.; Fullerton, A.S.; Moren Cross, J. More than just nickels and dimes: A cross-national analysis of working poverty in affluent democracies. Soc. Probl. 2010, 57, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stier, H. Working and Poor. In The State of the Nation: Society, Economy and Policy; Ben-David, D., Ed.; Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel: Jerusalem, Israel, 2011; pp. 135–180. [Google Scholar]

- Andreβ, H.J.; Lohmann, H. The Working Poor in Europe: Employment, Poverty and Globalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. A welfare state for the 21st century. In The Welfare State Reader; Pierson, C., Castles, F.G., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge UK, 2006; pp. 434–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, D. Insider–outsider politics in industrialized democracies: The challenge to social democratic parties. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2005, 99, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, D. Social democracy and active labour-market policies: Insiders, outsiders and the politics of employment promotion. Br. J. Political Sci. 2006, 36, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.; Bostic, A. Paradoxes of social policy: Welfare transfers, relative poverty, and redistribution preferences. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, N.; Pontusson, J. The structure of inequality and the politics of redistribution. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2011, 105, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHeuvelen, T. Unequal views of inequality: Cross-national support for redistribution, 1985–2011. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 64, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breznau, N.; Eger, M.A. Immigrant presence, group boundaries, and support for the welfare state in Western European societies. Acta Sociol. 2016, 59, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, S.; Gelepithis, M. Welfare State Structures, Inequality, and Public Attitudes Toward Progressive Taxation. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, Y. Explaining social policy preferences: Evidence from the Great Recession. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 107, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.; Citrin, J.; Conley, P. When Self-Interest Matters. Political Psychol. 2001, 22, 541–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Myrskylä, M. Always the third rail? Pension income and policy preferences in European democracies. Comp. Political Stud. 2009, 42, 1068–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughan, A. Economic insecurity and welfare preferences: A micro-level analysis. Comp. Politics 2007, 39, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Schlozman, K.L.; Verba, S. Insult to Injury: Unemployment, Class, and Political Response; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.F.; Giuliano, P. Preferences for Redistribution. In National Bureau of Economic Research; Working Paper No. 14825; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, S.; Zaller, J. The political culture of ambivalence: Ideological responses to the welfare state. Am. J. Political Sci. 1992, 36, 268–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.V.; Bell, W. Equality, success, and social justice in England and the United States. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 43, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, W.; Gelissen, J. Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Sociol. 2001, 44, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaud, E. Preferences for redistribution: An empirical analysis over 33 countries. J. Econ. Inequal. 2013, 11, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, H. Welfare states, labour market institutions and the working poor: A comparative analysis of 20 European countries. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 25, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeringer, P.B.; Piore, M. Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis; D.C. Heath and Company: Lexington, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Wallace, M.; Althauser, R.P. Economic segmentation, worker power, and income inequality. Am. J. Sociol. 1981, 87, 651–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.L.; Hodson, R.; Fligstein, N.D. Defrocking dualism: A new approach to defining industrial sectors. Soc. Sci. Res. 1981, 10, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindbeck, A.; Snower, D.J. Wage Setting, Unemployment, and Insider-Outsider Relations. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, B. Lean and Mean: Why Large Corporations Will Continue to Dominate the Global Economy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne, L.; Reskin, B.F.; Hudson, K. Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPrete, T.A.; Goux DMaurin, E.; Quesnel-Vallee, A. Work and pay in flexible and regulated labor markets: A generalized perspective on institutional evolution and inequality trends in Europe and the US. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2006, 24, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, C. Labor market inequality, past and future: A perspective from the United States. In Gender Segregation: Division of Work in Post-Industrial Welfare States; Gonas, L., Karlsson, J.C., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2006; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, L.G. Ethnic diversity and support for redistributive social policies. Soc. Forces 2016, 94, 1439–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaking, S.; Malmberg, J.; Sarkar, P. How do labour laws affect unemployment and the labor share of national income? The experience of six OECD countries, 1970–2010. Int. Labour Rev. 2014, 153, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Volume 1, Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The countries included in the surveys were: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States. |

| 2 | Missing information for specific years was linearly interpolated. |

| 3 | Alternatives to the OECD Indicators of Employment Protection have recently been developed. A notable example is the Cambridge Center for Business Research Labour Regulation Index (CBR-LRI), which focuses on the degree of protection instead of cost and comprises of 36 indicators providing yearly information and covering broad areas such as forms of employment, regulation of working time, regulation of dismissal, employee representation and industrial action [64]. Perhaps the greatest advantage of the CBR-LRI is the potential of disentangling the various dimensions of employment protection. However, this issue falls beyond the scope of the current paper. |

| Total | Non-Poor Workers | Working Poor | Poor Non-Workers | Non-Poor Non-Workers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Proportion | Mean/Proportion | Mean/Proportion | Mean/Proportion | Mean/Proportion | |

| Level 1 a | |||||

| Share of total population | 100 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Government should reduce income differences | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Disagree | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Neither agree or disagree | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.12 |

| Agree | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Strongly Agree | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.38 | 0.32 |

| Male | 0.5 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.4 | 0.35 |

| Age | 44.36 | 43.08 | 42.46 | 46.85 | 49.79 |

| (10.75) | (10.00) | (9.76) | (11.81) | (11.95) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Was married (divorced, separated or widowed) | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| Never married | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| Academic degree | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Religious | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| Self-employed in current or prior job | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Respondent supervises others in current or prior job | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| Level 2 | |||||

| Employment protection b | 1.89 | ||||

| (0.85) | |||||

| Unemployment insurance (share of GDP) c | 1.12 | ||||

| (0.79) | |||||

| Active labor market policies (share of GDP) c | 0.61 | ||||

| (0.42) | |||||

| Other transfer payments (share of GDP) c | 0.46 | ||||

| (0.42) | |||||

| N | 119,740 | ||||

| Nj | 179 | ||||

| Nk | 31 |

| Model 1 | Model2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects on Intercept | Effects on Non-Poor Workers Slope | Effects on Poor Non-Workers Slope | Effects on Non-Poor Non-Workers Slope | |||

| Level 1 | ||||||

| Non-poor Workers | −0.378 *** | −0.325 *** | −0.508 *** | |||

| (0.022) | (0.036) | (0.102) | ||||

| Poor non-workers | 0.329 *** | 0.215 *** | 0.358 ** | |||

| (0.034) | (0.036) | (0.122) | ||||

| Non-poor non-workers | −0.028 | −0.084 * | −0.157 | |||

| (0.025) | (0.037) | (0.108) | ||||

| Level 2 | ||||||

| Employment protection | 0.189 * | 0.104 * | −0.034 | 0.028 | ||

| (0.086) | (0.043) | (0.054) | (0.045) | |||

| Unemployment + active labor market | 0.016 ** | −0.005 | 0.076 | 0.034 | ||

| (0.067) | (0.043) | (0.054) | (0.044) | |||

| Other transfer payments | −0.1 | −0.017 | −0.214 | 0.04 | ||

| (0.145) | (0.085) | (0.134) | (0.098) | |||

| Cut points | ||||||

| Intercept 1 | −3.654 *** | −3.654 *** | −3.654 *** | |||

| (0.066) | (0.066) | (0.066) | ||||

| Intercept 2 | −1.978 *** | −1.978 *** | −1.978 *** | |||

| (0.065) | (0.065) | (0.065) | ||||

| Intercept 3 | −1.129 *** | −1.129 *** | −1.129 *** | |||

| (0.065) | (0.065) | (0.065) | ||||

| Intercept 4 | 0.749 *** | 0.749 *** | 0.749 *** | |||

| (0.065) | (0.065) | (0.065) | ||||

| Variance components | ||||||

| r0 | 0.066 | 0.126 | 0.128 | |||

| r1 | 0.107 | 0.10 | ||||

| r2 | 0.051 | 0.05 | ||||

| r3 | 0.078 | 0.08 | ||||

| uoo | 0.605 | 0.463 | 0.306 | |||

| Log likelihood | −344,584.6 | −344,551.8 | −346,966.8 | |||

| BIC | 695,675 | 690,798 | 690,724 | |||

| Nij | 119,740 | |||||

| Nj | 179 | |||||

| N | 31 | |||||

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levanon, A. Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor. Societies 2018, 8, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030072

Levanon A. Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor. Societies. 2018; 8(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevanon, Asaf. 2018. "Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor" Societies 8, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030072

APA StyleLevanon, A. (2018). Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor. Societies, 8(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030072