Abstract

Community stakeholders can be valuable allies to city officials engaged in downtown regeneration and community planning. This project highlights the force of engaging such allies in planning initiatives. It focuses on a long-neglected community that was once a thriving African American cultural and commercial hub. Organized as a city-university collaborative, the project brought together a cadre of community stakeholders: a planning studio professor and graduate students; a professional planner; architects; preservationists; and area residents, business owners and community leaders. Stakeholders held several meetings to evaluate the overall needs of the area, discuss options that would allow the concurrency of neighborhood revitalization, historic preservation and commercial economic interests while adhering to existing design guidelines. The group’s work culminated in a proposed land use plan that is sensitive to the needs of families, businesses and the city’s revitalization efforts. The plan calls for creating built spaces that complement the natural environment and encourages integrating green initiatives with regenerative efforts. It proposes creating active parks; cultural, arts and entertainment districts; and zoning that allows for single and multifamily housing. It transforms the district into one that is mixed-use, economically viable, family-oriented and preserves the area’s authentically historic and cultural assets.

1. Introduction

Community engagement, neighborhood regeneration and historic preservation form the triad that defines efforts to begin the process for restoring a rapidly declining historic treasure to a thriving, healthy community in which people live work and play. The Farish Street Historic District (District) provides an unparalleled opportunity for collaborative engagement. Rich in architectural, cultural and social history, the District has undergone drastic changes since its days as the hub of African American economic, cultural and social activity. During the first six months of 2009, residents, business owners and other community stakeholders shared their ideas, opinions and suggestions about efforts needed to make desired changes in the area and to arrest the rapid decline of this historic treasure. It is on this landscape that a community of stakeholders coalesced around efforts to combine elements of form-based zoning and comprehensive rezoning to respond to the continuous decline of Farish Street Historic District.

The Farish Street Historic District is an African American community located in the city of Jackson, Mississippi. The area’s growth and prosperity during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries are chronicled in scholarly research and publications devoted to historic preservation. Once a thriving Black commercial hub and residential area, Farish Street Historic District has undergone major changes since it transitioned from its former historically iconic states as a major African American district located in a state known for its repressive racial climate. Changes were punctuated by a steady decline in commercial activity as blacks took advantage of expanded opportunities in education and employment and the increased choices available in residential locations. The Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in March 1980 with an Amendment in October of the same year [1]. By 2000, the District had been all but decimated despite the designation as a historically significant architectural and cultural community.

1.1. Planning for Community Regeneration

Citizen engagement in decision making can produce desirable results when that engagement is meaningful and participants in the process believe their input is valuable to the process and in effecting outcomes. Attracting various stakeholders to the table to accomplish specific tasks can be as contentious as it is rewarding. The influence that citizen involvement has on decisions remains a point of debate [2]. Further, as Forester [3] observed, public deliberations involve processes of “dialogue, debate and negotiation fostered by the three deliberative practices of facilitating, moderating and debate (p. 304).” Collaborations may prove difficult to maintain in the face of competing interests. Facilitators must properly manage stakeholder conflict and divergent opinions in ways that promote and engender trust [4]. When taking shortcuts to achieve collaborative planning, the outcome will be less than desirable whereas earnestly enjoining appropriate and substantive participatory processes will likely prove satisfying in spite of the extra time devoted to the process [3].

Community stakeholders can be empowered via increased participation. When they take more active roles in shaping policies that govern their lives, they may feel a greater sense of control over the decisions that impact their communities. They may also grow to expect more from the people who represent them and they will likely believe they are entitled to more information [5] in order to make more informed decisions. Collaborative planning offers decision-makers opportunities to be more inclusive and more sensitive to cultural differences, while inviting greater participation from community stakeholders [6].

Involvement at the community level can be disappointing. Participation during initial stages may be high only to dissipate as projects move forward [7]. Planners and others engaged in service to communities would be well advised to ask what participatory and collaborative mean [3] Arnstein [8] provided a blueprint that demonstrates the difference between token participation and substantive engagement where collaboration and participatory processes are respected and honored. Meaningful participation must include those who will be most affected by changes arising from policies and decisions [9].

The new emphasis on sustainability may benefit communities in unanticipated ways. In the past, economic development often trumped social and cultural considerations in regenerative efforts. It is difficult to connect the theoretical with the practical needs of at risk communities that have endured decades of neglect. In his abstract on Rethinking Sustainable Urban Development, Jones [10] wrote:

… the notion of sustainability acts as a shared territory for meaning around which diverse stakeholder groups coalesce and show how the ambiguity inherent in this shared conception can generate more creative (and sustainable) outcomes to developmental challenges. Viewing sustainability as a shared territory makes ambiguity not only intelligible but also desirable to the development process ….(p. 141)

With more emphasis on development and revitalization as sustainable, the integration of social environmental and economic concerns has become the preferred way of viewing regeneration [11].

1.2. Project Objectives: Stakeholder Participation in Community Planning

The overarching objective of the project was to engage community residents and other stakeholders in efforts to create a rezoning plan that would help guide development in the Farish Street Area Mixed-Use District that would allow the concurrency of neighborhood revitalization, cultural history, architectural integrity and historic preservation while adhering to existing design guidelines. If stakeholders were successful in proposing an adoptable plan that remained true to the objective, they would have succeeded in protecting the unique character of the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District. Attendant benefits to viable rezoning would be the creation of an authentic but historically protected mixed-use district and the promotion of education, pleasure and community welfare. Further, the plan encouraged a healthy mix of residential, commercial, recreational arts and retail, essential elements for developing viable economic activity.

Another objective was to help create stakeholder awareness about the benefits of healthy places by giving greater attention to the link between the natural and built environments and how they intersect to produce healthy spaces where people live, work and play. The proposed plan reduced auto dependency and increased a pedestrian friendly environment. A major consideration of the plan was its impact upon the land use portion of Jackson’s Comprehensive Plan for the Downtown Regional Mixed-Use Center.

2. The Farish Street Historic District

The Farish Street Historic District is adjacent to the downtown area of Jackson, the capital of Mississippi. The City was founded in 1821 and incorporated in 1822 [12]. Prior to the Civil War, much of the area now located within the District belonged to large estates that were later divided into the segregated community peopled by free blacks. Jackson’s population and commercial enterprises grew slowly during the 1800s but gained momentum after the Civil War and by the turn of the century, Jackson began to experience an impressive growth in population as well as economic enterprises and municipal services [13]. During the same period, Farish Street became a firmly established African American commercial hub.

The vestiges of slavery and Jim Crow left an indelible mark on the entire state and an enduring impact on the condition of blacks whose access to social and economic opportunity was blocked at every turn [14]. Yet, in the face of the harsh realities imposed by stark segregation and oppression, blacks in the Farish Street area developed a thriving economically independent community inhabited by professional, independent businessmen, tradesmen, craftsmen and talented residents who carved out spaces of hope and success. Once a thriving city with a majority white population, Jackson’s current population has a black to white ratio of 79% to 18% [15]. Since the 1960s, the City has lost population to outmigration of residents and businesses, a trend that mirrors the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District.

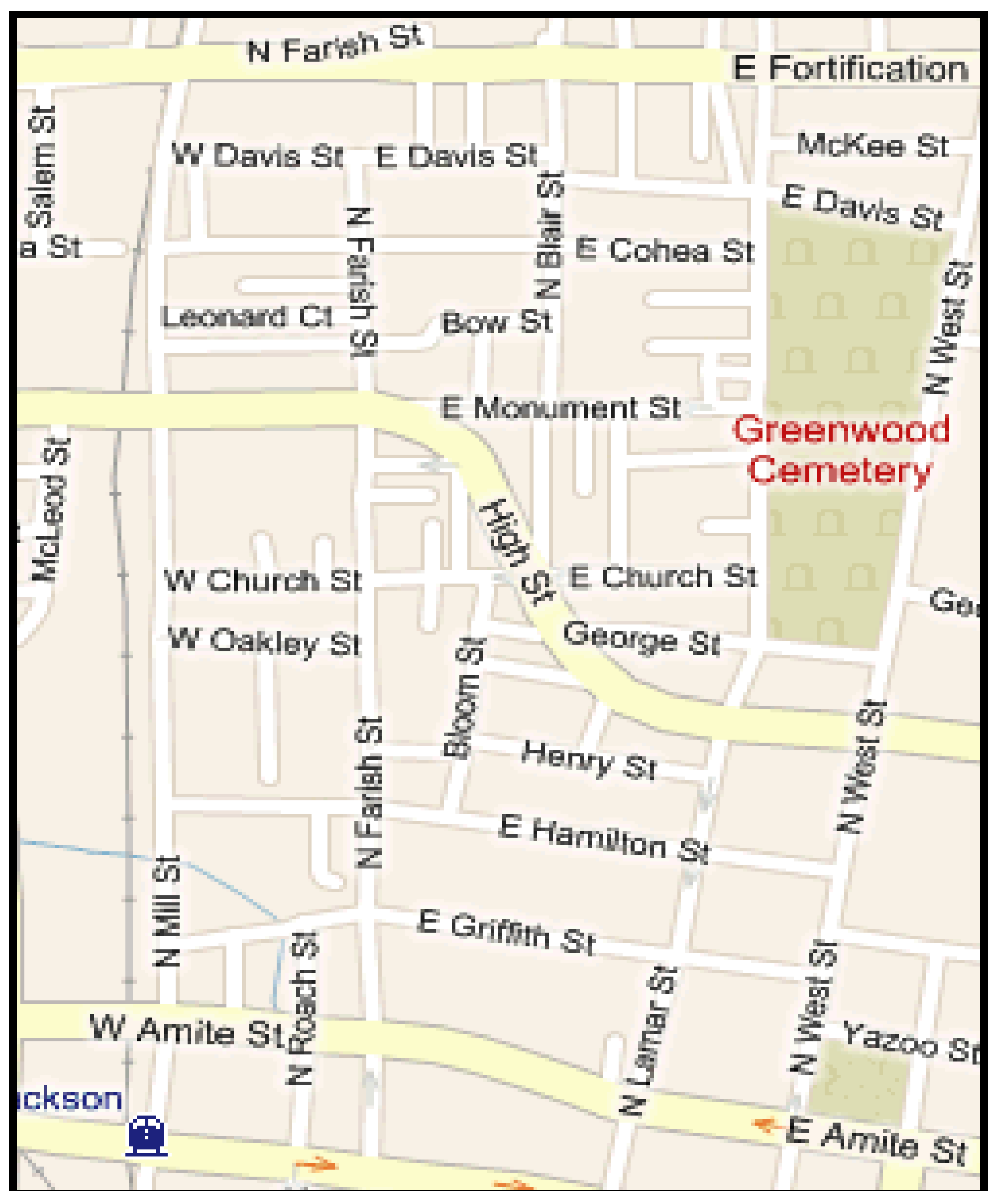

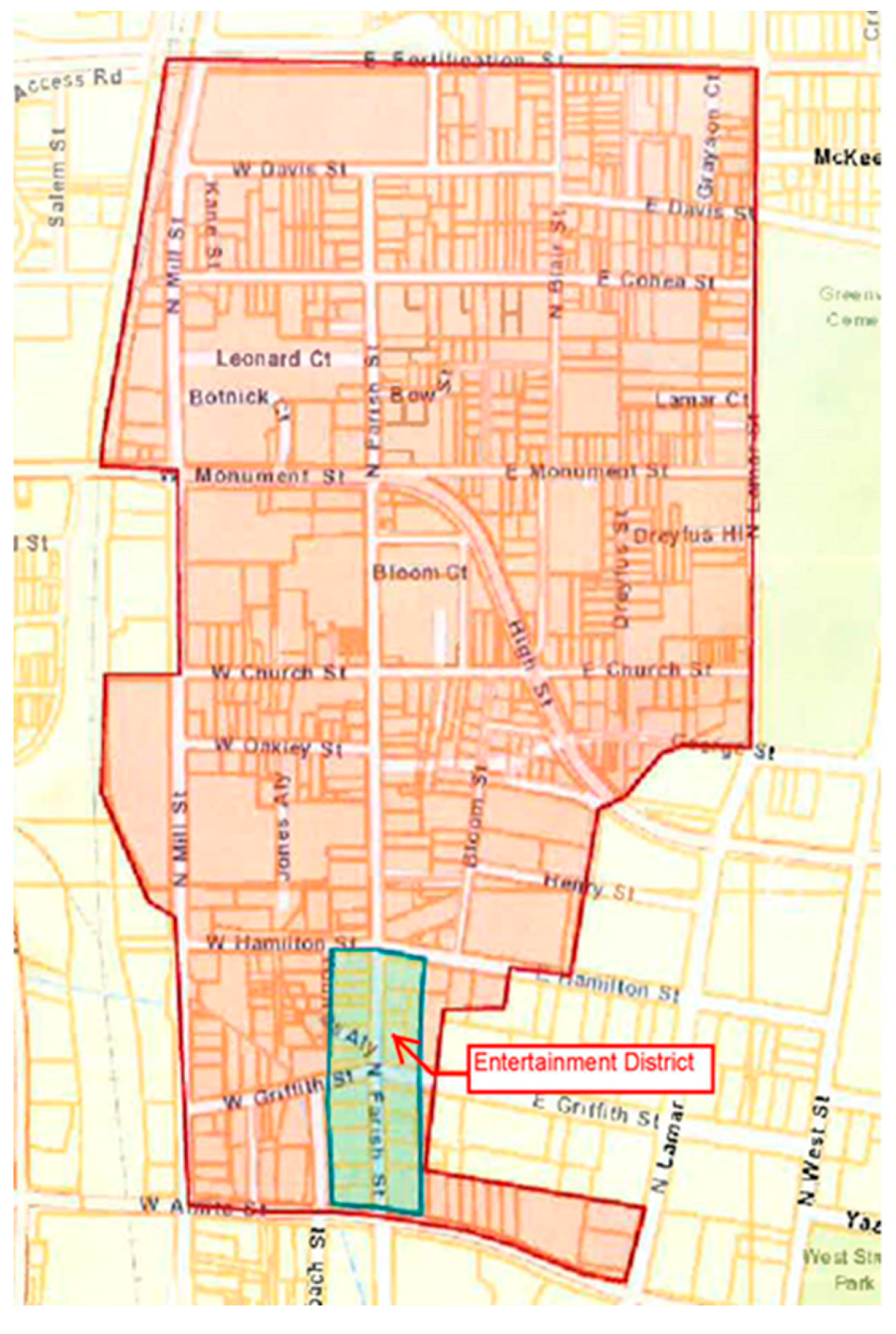

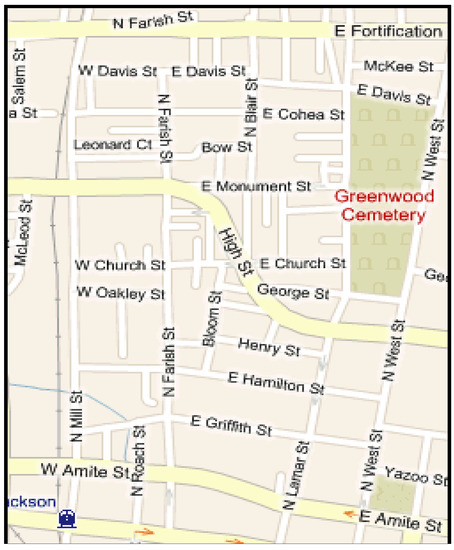

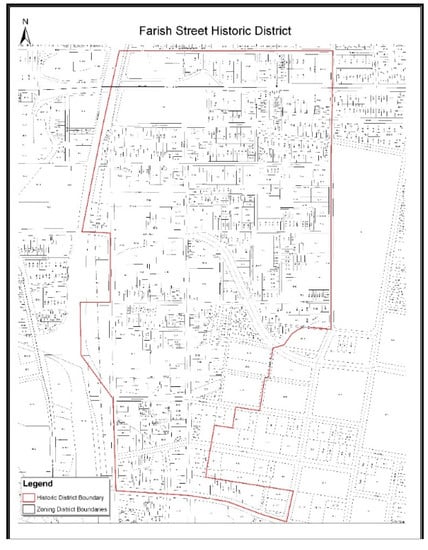

Farish Street Historic District is bound by Fortification Street to the north, Amite Street to the south, Lamar Street to the east and Mill Street to the west (Figure 1). The area comprises approximately 189 acres of prime property with 607 parcels of land (Figure 2). Because the District is located contiguous to the central business district and within walking distance to historic Union Station, Jackson’s multi-modal transportation facility and the newly restored King Edward Hotel, it is in an advantageous position for development, which has been attempted several times in the past.

Figure 1.

Farish Street Historic District Boundaries.

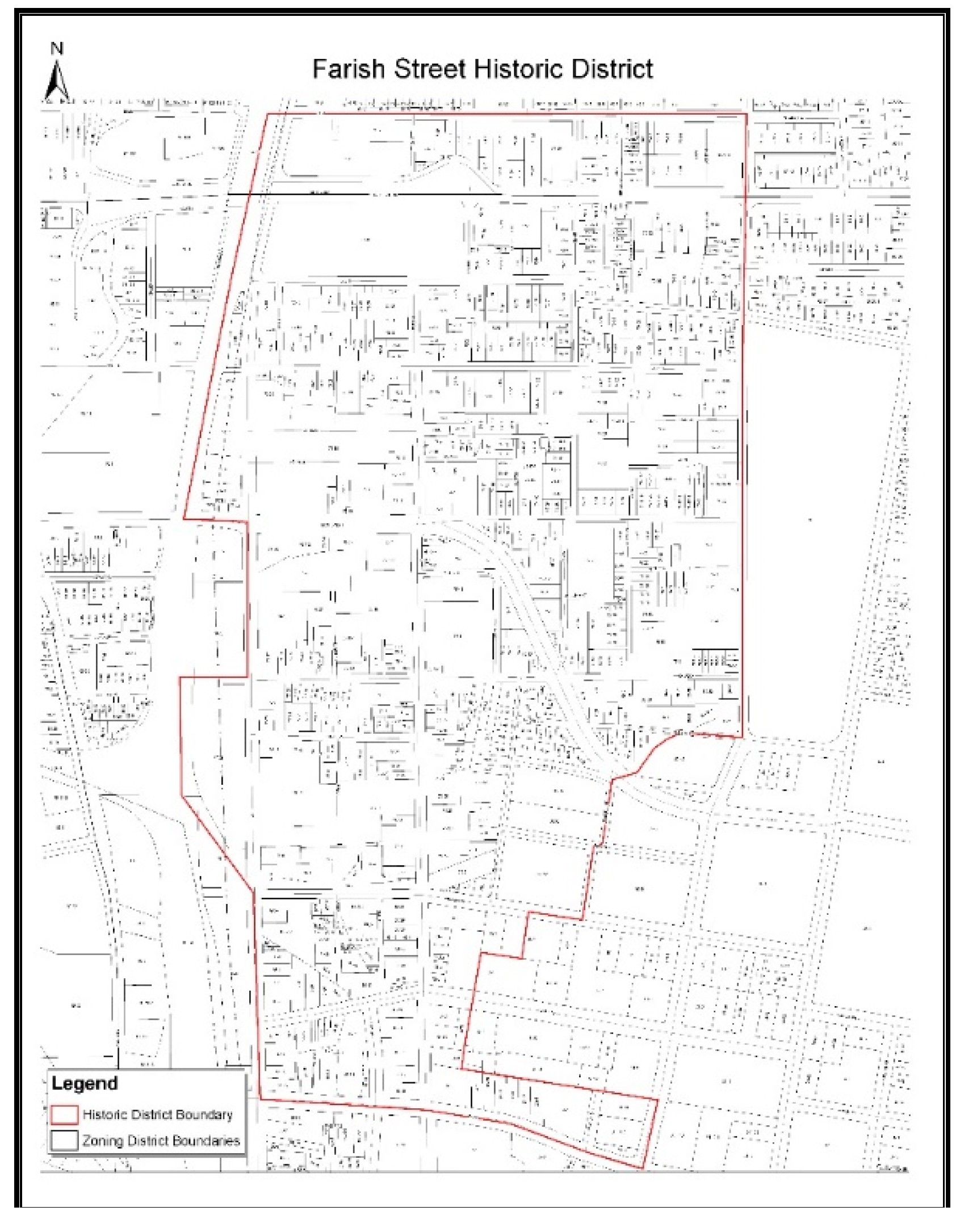

Figure 2.

Farish Street Historic District. Source: Planning Department, Jackson, MS Source: Planning Department, Jackson, MS.

The decline of the Farish Street Historic District may be attributable, in part, to changes that have taken place in urban areas throughout the nation. However, the changes became most obvious when Jackson’s population shifted from majority white to majority black. As many businesses and area residents moved away from the City, preferring instead to relocate to the emerging suburban areas, the remaining businesses began a downward spiral.

The impact of outmigration, suburbanization and general disinterest in downtown living left the District neglected and abandoned. The lack of enough activity to support viable enterprises left the Farish Street area decimated. Despite the efforts of preservationists and other stakeholders to restore the area to a state that approximates the former District, little progress has been realized. Local interests in restoring the area into a vibrant community have been uneven. Various efforts by community stakeholders, city agencies and others to redevelop the area have seen little sustained success.

From Loss of Place to Endangered Treasure

The Farish Street Neighborhood is the oldest known black business district in the nation and “… the only African American Historic District listed on the National Register that was built by former slaves whose great-great grandchildren still work and live in the area” [16]. At one time, the Farish Street Historic District was one of Mississippi’s most economically viable African American communities [17]. Its listing as both a National Historic District and a Jackson Historic District provides the area with national recognition and local support to protect the historical integrity of the District [18] and ensure its survival as a national treasure. Farish Street is significant for its place in the history of Jackson as well as it is for telling the story of African Americans in that history. According to Alferdteen Harrison [19]:

Farish Street has a significance to Jackson, Mississippi, that 18th and Vine have to Kansas City, Missouri; Beale Street to Memphis, Tennessee; Rampart Street to New Orleans and South Parkway to Chicago. Historically, these streets were centers of black cultural activity.(p. 1)

Researchers and preservationists appear fascinated with the community’s culture and heritage as well as the rich architecture and famous shotgun houses associated with an historical era during which the Farish Street Historic District flourished [20,21]. The creation of sense of place by early inhabitants of Farish Street during the late 1800s and the early to mid 1900s continues to resonate with the remaining residents and business owners who lived and worked in the District.

Farish Street was a mixed-use community predating the recently acclaimed New Urbanism. Residents lived and worked in the same area and living quarters were often attached to business establishments. Churches doubled as places to host cultural events. Social and civic clubs formed and grew and famous musicians entertained blacks in the District as they stopped there en route to larger venues such as Memphis or New Orleans [22].

It is difficult to overstate the sense of place created by the community of people who lived, worked and owned businesses in the Farish Street District. The history of the area is telling when recounted by historians, researchers, former and current residents. Aurelia Norris Young [23] described the type of work performed by these people. They were craftsmen and tradesmen, letter carriers and porters. The women worked as cooks, maids, seamstresses and managers of white rooming houses. Young also pointed out that women who were not employed outside of the home often sold the items they created from “… weaving, spinning, knitting, crocheting, quilting making … (p. 5).”

Visits by rural dwellers to Farish Street on Saturday made for an all-day affair where people “sold produce, artifacts and home-made cookies, cakes and pies” [22] (p. 4). Farish Street was a self-contained community. It had bankers, physicians, newspaper publishers, builders and prominent leaders [23]. The area also offered cultural amenities. The neighborhood hosted four movie theatres: The Alamo Theater on Farish Street, the Ritz, the Booker T. Washington and the Amite Theater, located on Amite Street, the southern border of Farish Street [24]. The Alamo Theatre, a designated National Landmark, was restored and serves as a venue where visitors and locals attend events and performances (Figure 3). By all accounts, this self-contained, segregated community was represented by every profession, craft and general talent that any town or city could boast.

Figure 3.

The Alamo Theater on Farish Street.

In an era of sprawling suburbanization and the quest for bigger and new housing, older neighborhoods generally do not hold as great attractions to homebuyers as newer homes with modern amenities, energy efficient comforts and the novelty of first owner occupied units. The advantages of preserving and living in older homes and neighborhoods are often eclipsed by the push to own something new. However, several advantages accompany living in older historic neighborhoods such as proximity to work, schools, shopping and transportation as well and affordable housing in reparable condition [25].

Many homes in the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District have fallen into disrepair that exceeds the need for minor repairs. The more than 30 shotgun houses restored during the late 1990s remain a controversial issue with varying opinions about their status as a historical asset. The foundation responsible for managing the project is essentially defunct [26]. The ongoing struggle to preserve the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District appears to be a never-ending task. In an effort to address the most critical barriers that hamper the progress to restoring and preserving the historical assets that are uniquely Farish Street, the City of Jackson continues to explore ways to ensure that this local and national treasure does not fade into oblivion. Many believe the only way to preempt such a calamity is to bring area residents, business owners and other stakeholders to the table to have a conversation around the downward spiral of the area. A major point to resolve is to determine appropriate rezoning that will protect the historical, architectural and cultural integrity of the Farish Street Historic District.

3. Data Collection and Methods

Data for the project were collected from both primary and secondary sources. These sources included city documents, publications chronicling the history of the Farish Street Historic District, archival documents from the Mississippi Heritage Trust, online resources specific to the study area and onsite visits to experience the overall condition of the community and to photograph key structures. Community stakeholders provided knowledge about the area, its residents, business owners and local activity about significant institutional and historical information that was crucial to understanding the significant role played by the District’s forebears. The information was later used to assign names to the proposed districts which reflected and honored the rich historical past. Urban and Regional Planning students became active participants in the process both in class and at stakeholder meetings.

Data from city documents were collected from the following sources: Zoning Ordinance for Jackson, Mississippi, adopted 29 May 1974 with Amendments, Last Amendment 21 June 2018; Design Guidelines for the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District; and City of Jackson Historic Preservation Ordinance, Adopted 25 May 2004. Additionally, project participants made use of the City’s land use reference guide and land use classification codes.

A series of meetings was held within the target area: Weekly stakeholder meetings; one general community meeting; and one-on-one meetings with individual residents and business owners. These gatherings were structured to bring key stakeholders to the table who could provide representation and input about District community and business needs as well as professionals with expertise in planning, architecture and historic preservation.

4. Results: Creating a Community of Choice

Archival research, onsite visits and related fieldwork and document compilation began in January 2009. Invitation letters were sent to key stakeholders who would become the core group assuming responsibility for providing expert advice and ensuring meaningful community outreach and engagement. The core group was comprised of pastors from the District’s churches, an architect and a landscape architect, engineers, Downtown Jackson Partners, a development group, a representative from Mississippi Historic Preservation, preservation advocates, city officials and engineers. The letters of invitation were sent in February followed in March by the initial meeting with the core members. Each stakeholder was asked to identify a person who lived in the area to participate in the meetings.

4.1. Organizing and Convening Meetings

The Studio professor and City Zoning Manager organized, convened and participated in seven meetings between 6 March and 21 May 2009. All were held in churches located in the Farish Street community (Table 1). The number of stakeholders participating in the meetings ranged from 15–25. It was difficult to determine the exact number of participants at each meeting because some attendees preferred to not sign in using the sign-in sheet available at each meeting.

Table 1.

Farish Street Historic District Community Meetings.

When determining the amount of time devoted to meetings, organizers decided to limit sessions to no more than two hours. They developed clear tasks to be completed at each meeting in order to avoid long sessions while allowing time for participants to engage in unhurried opportunities for asking questions and receiving answers. During the first meeting on 6 March 2009 the core group reviewed and discussed draft documents and data collected during archival research, onsite visits and related fieldwork. They organized and laid the groundwork for future meetings to engage community members. The meeting lasted for approximately two hours. Participants received an overview of the charge to develop a mixed-use district and rezoning plan for the Farish Street area.

The seven meetings provided opportunities for information gathering and exchange. Each meeting built upon information shared during the previous ones. Whereas participants in the first meeting offered technical and expert guidance, community meetings revealed historical information that relied upon local knowledge and lived experiences. Storytelling provided backstories about the evolution of Farish Street from a thriving African American community to one with abandoned, deteriorating businesses and homes accompanied by population outmigration. Concurrently, resident storytellers helped identify the names of early residents, forebears and nascent community icons. Knowledgeable residents in conjunction with historical and archival research helped determine appropriate assignation of District names, giving them greater historical significance.

4.2. One-on-One Meetings

A small number of one-on-one meetings occurred during the same time frame. A handful of residents and business owners requested individual meetings in order to discuss their concerns. For example, one business owner who worked for years in the area attended the community meeting but requested more personal interaction to get assurance that her business would not be adversely impacted by proposed changes. Personalizing the opportunity to engage in discussions about the proposed plan allowed individuals to engage freely in substantive conversations in a safe, non-threatening and familiar environment. Having worked in the area for many years, the City Zoning Manager had developed a trust level with many area stakeholders who were comfortable with talking about the Farish Street Area Mixed Use (FSA-MUD) proposal in privacy.

Specific issues discussed in one-on-one meetings included concerns about losing the area’s historic significance and unique identity. Would new businesses cause an increase in property taxes? As descendants of original inhabitants of Farish Street, would they lose their properties if required to upgrade even if they were unable to afford such upgrades or improvements? Would developers try to change Farish Street into a Memphis, Tennessee Beale Street or a New Orleans French Quarter? What about traffic and parking for businesses? The City Zoning Manager utilized the individual time with concerned community members to explain in greater detail the purpose of developing the plan and the benefits to residents. Assurances appeared to allay the skepticism experienced by some business owners whose modest livings might easily be upset by the arrival of new businesses with more sophisticated and polished marketing practices.

4.3. The Community Meeting

On 31 March 2009, Project collaborators convened a widely announced meeting with community-wide stakeholders. The meeting was attended by community members, City of Jackson officials and several members of the core group. Students from the Studio class participated in and assisted with the meeting. Participants took advantage of the opportunity to review, discuss and compare the proposed FSA-MUD and the existing land use map. They provided significant insight about possible changes and improvements that would preserve historical relevance, restore economic viability and advance community sustainability. Participants presented ideas about mixed uses; they suggested names for the Districts that would reflect the authentic Farish Street when it was a viable residential and commercial area.

4.4. Disseminating Information for Maximum Participation

The area’s population was and remains, very small. Many were renters who lived off limited incomes and may not have had ready access to available technology such as email or the skills to use it. Project collaborators disseminated information using a variety of reliable avenues to conduct community outreach and engagement. Invitation flyers were used to announce meetings. Students, community members and city staff handed out flyers door to door in the community and posted them in the few remaining businesses, including the small print shop located on the main corridor. Pastors published information in church bulletins and made invitational announcements during church services. Residents and stakeholders were encouraged to share information through personal contact with community members and other interested stakeholders.

4.5. Organizing for Interactive Work and Community Feedback

Meeting formats encouraged interaction between facilitators and participants. Zoning and land use maps were displayed and attendees engaged with meeting facilitators to ask and answer questions. Facilitators asked community members to share ideas about the area. Questions were open ended to invite conversation. Some of the questions posed were: What would you like to see in the Farish Street area? What concerns do you have about your community? Can you share the kinds of improvements you would like to happen in the Farish Street area? Discuss some positive aspects about the community. What would you like to see come out of these meetings? What do consider the most important aspects of the community you would like to preserve? Participants were also asked what they thought about the proposed FSA-MUD and what they would change, add or remove.

Large flip charts were used to capture feedback from participants with stories to tell, observations to make, questions to explore and ideas to share. Participants also asked questions about the proposed plan and provided input about what businesses they wanted in the area, the types of housing they preferred and the desire to have safe and attractive parks and other public spaces. The information captured during each session was shared with participants at the next meeting. This process allowed the Project principals to accrue data, build upon previous information and identify recurring issues, concerns and items of importance.

4.6. What Community Members Wanted

A number of concerns emerged during the meetings and participants shared them with the facilitators. Specific items included:

- Documenting and maintaining the area’s history.

- Ideas for mitigating problems related to untended and abandoned properties owned by absentee landlords.

- Examining current conditions for repurposing buildings and rezoning the area.

- Eliminating problem areas, specifically one used for industrial purposes.

- Enforcing codes more conducive to attracting businesses and residents to the area.

- Bringing structures up to code, which was also a concern of business persons who wanted to know how the proposed zoning might impact their businesses. Would they have to incur additional expenses to upgrade structures to bring them into compliance?

- Concerns about dilapidated houses, vacant properties, vagrant activities and crime.

- Reactivating the neighborhood organization.

While Project facilitators queried residents about what they thought of the proposed plan and encouraged them to share their ideas and opinions about the FSA-MUD, residents eagerly expressed concerns about day-to-day aggravations. Nonetheless, they connected the benefits of a rezoned and vibrant mixed-use community to community health and wellness. Overall, they considered the plan one that would help address some of the deteriorating conditions. Business owners expressed some degree of hopefulness mixed with skepticism that more traffic along the Farish Street corridor might actually boost business. Residents and property owners who did not live in the area considered development of new housing a benefit that could offset deteriorating homes and attract a mixture of market rate and affordable housing.

Information gathered from stakeholder and community meetings and individual sessions provided critical information that helped inform the final FSA-MUD. In particular, the language used to guide development and land use activities drew heavily from stakeholders’ input. Community concerns about preserving the authentic assets of Farish Street factored significantly into naming the Districts. When combined with Design Guidelines for the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District, community concerns and general feedback underscored the need for the City of Jackson to work more proactively to develop the area and attract businesses that complement the characteristics of this historic community. The FSA-MUD integrated all of these elements, attempting to advance efforts to redevelop the area into one that is safe, pedestrian friendly, historically authentic and attractive to businesses and potential homeowners.

5. Discussion

In an effort to move the Farish Street District from the idea and planning stage to concrete proposal, the collaborating professor and Zoning Manager spearheading the project and the Studio professor focused on process. The process revolved around salient information collected and reviewed for use in preparing a plan, scheduling community outreach to invite participation, developing a proposed rezoning plan and reviewing and obtaining approval of the area plan. Graduate students participating in the project assisted with moving project work forward in order to complete it within a limited amount of time.

Citizen participation in the community and neighborhood revitalization was a critical component in creating a plan that invited buy-in. Sensitive to the emotional and economic investment of area residents and other stakeholders in the District, the planner focused on community inclusiveness. To achieve this goal, stakeholders met weekly for a designated period of time, attended a general community meeting and the planner held individual sessions to answer questions for persons requiring additional information and explanation. The process focused on citizen engagement, technical advice and guidance, roundtable and open group work to identify needs and craft a rezoning document that would allow for the concurrency of development and protection of the historic integrity through rezoning. The end product would be a land-use map to guide the community toward an economic and social sustainability.

5.1. Weekly Stakeholder Meetings

Weekly meetings were scheduled early in the planning process. They were held at a church located on Farish Street and included a core group of stakeholders who represented the Farish Street community, architects, preservationists, potential development entities, the City planning department, Urban and Regional Planning students from Jackson State University and other persons interested in the District’s future. A general community meeting was held at a different church within the District later in the process. The lead collaborators facilitated the meetings. Participating stakeholders throughout the process included architects, preservationists, local citizens and graduate students in the Neighborhood Revitalization/Urban Revitalization Studio from Jackson State University’s planning department. Participants were invited to provide input and assistance in developing a recommended plan for the District.

Different tasks were performed at each meeting. During the first meeting, participants received briefings about Farish Street, the history, District design guidelines and the City’s preservation ordinance. They received copies of the current zoning ordinances and maps of existing zoning in the area. Subsequent meetings engaged participants in more extensive exchange as they became more familiar with existing zoning and the desire to move forward on plans to rezone the District. One of the last meetings engaged attendees in developing maps that captured their thoughts about what rezoning for the area should take place. Professionals, including members of development teams, the director of planning and architects were invited to the meetings to provide advice, suggestions and ideas about rezoning.

Assigned Tasks

Each meeting followed a planned agenda designed to encourage stakeholders to explore redevelopment and rezoning ideas for the District, invite comments and suggestions and to anticipate challenges and questions about any plan produced. The meetings covered specific tasks in which participants engaged.

5.2. Community Meetings

Community meetings held in an area church attracted local residents, business owners and ministers who pastor churches in the Farish Street Historic District. The meeting provided a forum in which participants shared their experiences about the area, their opinions and suggestions regarding how to make appropriate intervention to stem the rapid decline of the area. The information was recorded by participating students and became a part of the report written by the Studio group. At least one church pastor and some residents voiced ongoing concerns about using the Farish Street Neighborhood as a “dumping ground” for other unwanted land uses in the City.

Several participants at the community meeting were longtime residents and provided invaluable historical knowledge about the area, progress made, challenges encountered and ongoing efforts to restore the District to a viable community. Older residents provided particularly rich history by the recounting their lived experiences to students and others attending the meeting. Capturing this shared history remains a valuable way to collect information about older declining communities from aging residents who willingly share their stories. According to Thomas (2004) oral history by older residents provides invaluable information to researchers working to reconstruct and authenticate the past of an area that is at risk for permanent loss.

5.3. Student Participation and Contributions

In addition to area stakeholder meetings, the Senior Planner/Land Use Manager and Studio Professor engaged Studio graduate students in activities that expanded the capability to complete the designated work within the course of a semester. Studio participants developed plans of work, provided suggestions for zoning and redevelopment in the area and drew proposed zoning maps for the District guided by Jackson’s zoning ordinances and the existing design guidelines for the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District. Students assisted with the general community meeting and crafted a report that documented observations regarding stakeholder participation and concerns, provided suggestions and recommendations specific to community engagement and presented ideas for signage and proposed gateways. In addition to participating in community and stakeholder meetings, students took a major role in the community meeting. Their work produced a written document, General Community Meeting: Assessment and Report, which provided:

- Historical overview of the Farish Street Historic District

- Purpose of the meetings

- Information and issues discussed by meeting participants, their concerns and ideas for rezoning

- Suggestions/Recommendations

5.4. One-on-One Meetings with Community Residents and Business Owners

An unexpected issue arose that had to be diffused. Some residents and business owners expressed the need to receive additional information and briefing about efforts to rezone the area. They were more comfortable with one-on-one discussions with the senior planner/Land Use Manager where they could comfortably and privately state objections, ask questions and voice opinions and disagreements. They needed assurance that their businesses would not be harmed, or they would not be forced to relocate their businesses or homes. These individual sessions afforded affected stakeholders to gain greater knowledge and understanding about the process, proposed zoning and related issues.

6. Outcomes

Participants in the project realized several outcomes. The collaborative culminated in a comprehensive rezoning document and land use map for the area that allows for the concurrency of neighborhood revitalization and historic preservation while adhering to existing design guidelines. The land use plan proposed by the group remained sensitive to the needs of families, businesses and the city’s revitalization efforts. Borrowing from the basic tenets of form based zoning and guided by the current zoning and preservation ordinances, stakeholders helped develop a land-use plan and rezoning proposal to guide development in the Farish Street Historic District. In addition to creating new language for the rezoning, the document proposed to:

- Create built spaces that complement the natural environment and encourage integrating green initiatives with regenerative efforts.

- Create space for active and inactive parks.

- Create cultural, arts and entertainment districts.

- Create zoning to allow for single and multifamily housing with provisions for childcare.

- Allow for compatible in-home businesses and above-business into one that transforms the District into one of mixed-use, economically viable and family-oriented.

- Preserve the area’s authentically historic and cultural assets.

- Encourage a healthy, walkable and more livable community.

- Protect existing businesses from the proposed rezoning.

6.1. Restoring Place

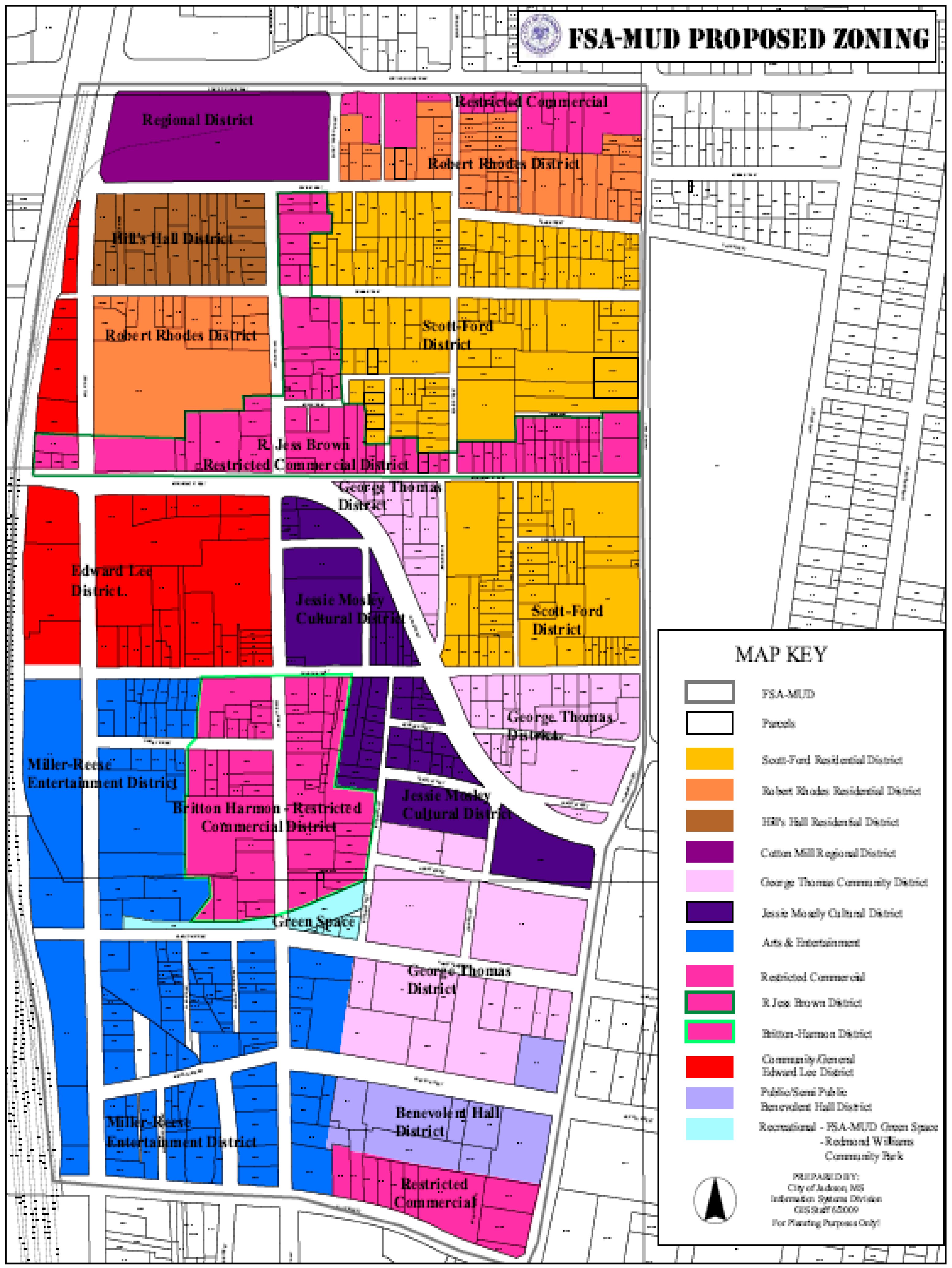

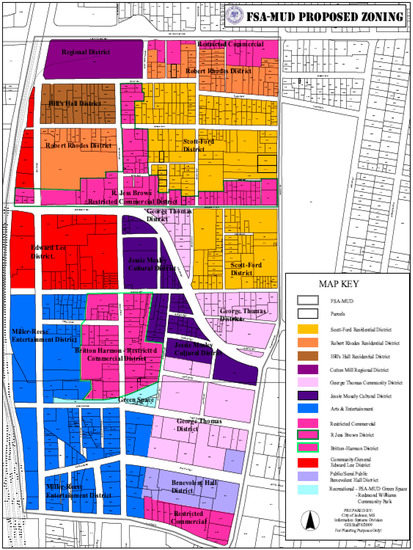

The concept of sense of place and the disruption of place associated with loss can help planners and community workers understand the profound impact such losses can have on emotional, physical and communal connections [27]. As project members worked in groups for six months, engaging stakeholders in conversation about ideas to restore Farish Street, the loss of a vibrant community became palpable. The proposed FSA-MUD was a bold effort to respond to the loss of culture, history and community and to restore a sense of place. The final plan proposed rezoning to create the Farish Street Area Mixed Use District (FSA-MUD). It called for establishing specific districts and sub districts, each named for a notable or historically relevant personality, facility or structure. They included: Residential Districts with both single and multi-family housing; Commercial Districts, Cultural and Arts/Entertainment Districts and Other Districts that included public districts and green spaces (Figure 4, Table 2). Each of the Districts held specific meaning to participants and the names were tied to early inhabitants of Farish Street and reflect their professions or contributions they made to the area. The language of the document captured the full intent [28].

Figure 4.

Farish Street Area Mixed Use District (FSA MUD) Proposed Zoning Map. Source: Planning Department, Jackson, MS.

Table 2.

Proposed FSA-MUD Districts.

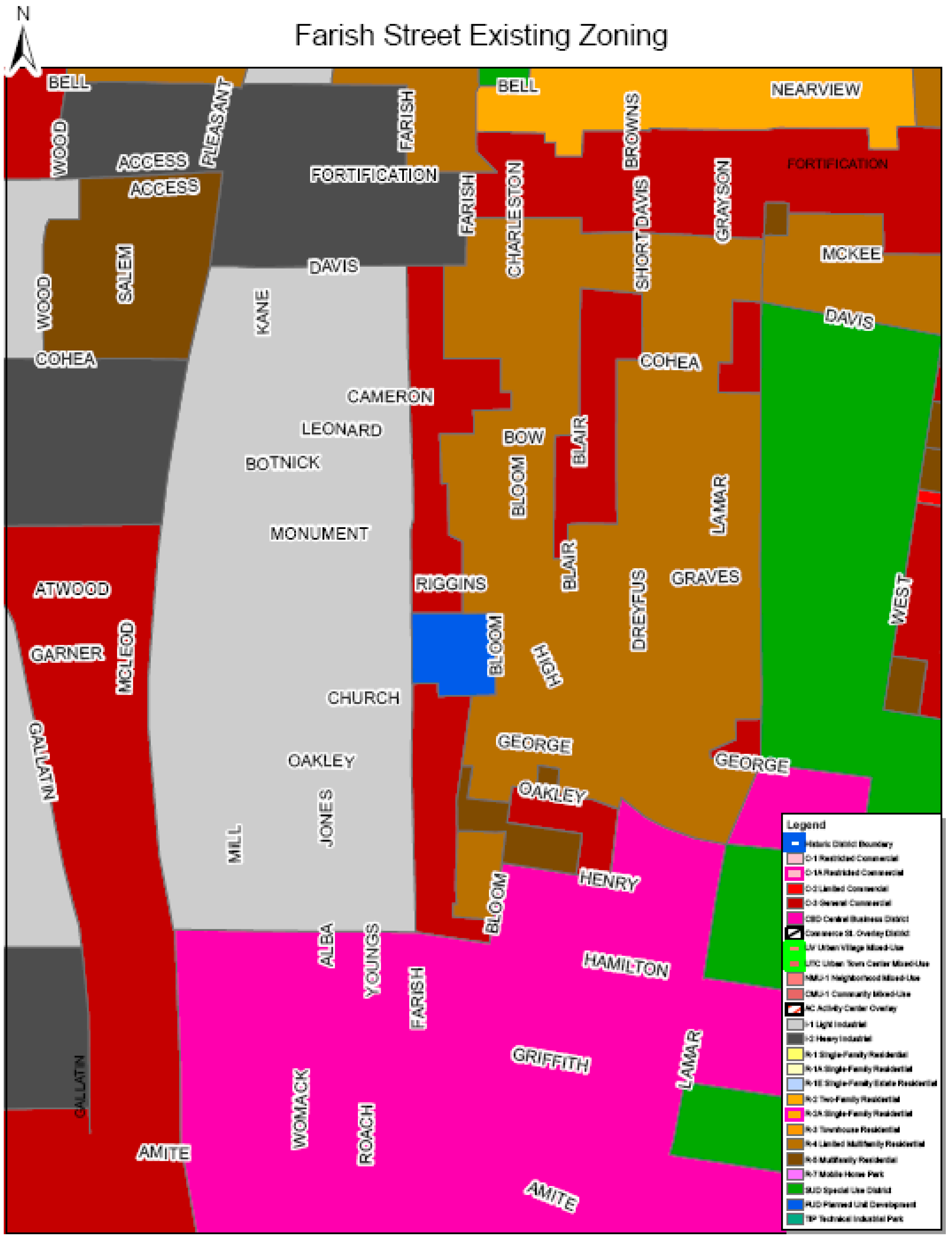

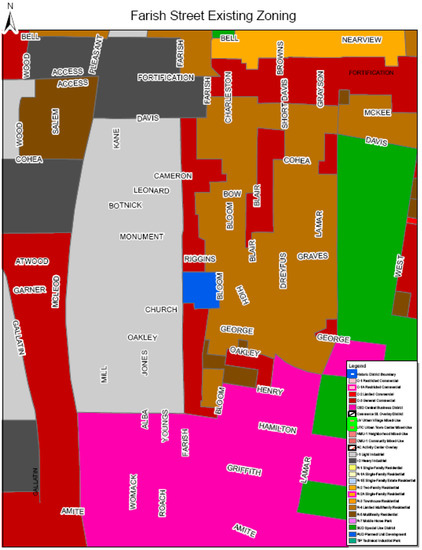

The purpose and intent of the Farish Street Area Mixed Used District (hereinafter referred to as FSA-MUD) is to preserve the cultural and architectural history of the Farish Street community. The FSA-MUD is designed to protect the unique character of the Farish Street area and promote the district for the education, pleasure and general welfare of the local community and the City of Jackson. The intent of the FSA-MUD is to encourage the healthy mix of residential, commercial, recreational, arts and retail uses in Downtown with an improved pedestrian environment. The FSA-MUD is compatible with the Downtown Regional Mixed-Use Center found in the Land Use Plan portion of Jackson’s Comprehensive Plan. Article VII-A, Section 708.A. It remains a significant improvement over the existing 2009 Farish Street zoning (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Farish Street Zoning Map 2009. Source: Planning Department, Jackson, Mississippi.

Another argument posed was that many plans had been presented and initiated in the past to move forward on revitalization of the area, yet little to nothing had been done and the area was continuing to decline and a rapid pace. Sill, others considered the proposed plan to be an impediment to opportunities to place the types of businesses they wished to have. They considered the proposed zoning too restrictive. Of particular concern to a handful of business owners operating in the District was how it might affect their existing businesses. Would they be able to continue doing business? What kind of economic impact would the rezoning have on taxes and restrictions on customer parking? These questions were answered with demonstrations of maps and explanations about the proposed rezoning language. Although the argument received traction and support from some persons attending the meetings, other participants wanted to retain the status, viewing it as a way to affirm the area’s historical significance and authenticity. Some members of the community, many of whom had worked tirelessly for revitalization for many years, were not as enthusiastic about the proposed rezoning because of concerns it might erode the unique characteristics and historical significance of the Farish Street community.

6.2. Unanticipated Outcome: Appeals to Proposed Rezoning

The proposed rezoning was presented to the Planning Board in May 2009. The Board passed the Future Land Use and rezoning plans unanimously. The plan was scheduled to be presented to the City Council in July 2009 with recommendation for approval [29]. Appeals submitted to the Administration challenged the Board-approved rezoning. The appellants to the Administration cited several reasons for their positions including insufficient time and discussion of the proposed rezoning; no representation during discussions to explore the impact on tourism and economic development and the potential adverse impact that mixed-use, as proposed, would have on the District.

The proposal did not go before the City Council for action as scheduled. Rather, the Administration pulled it just prior to the City Council meeting. Comments by Council members, if any, remain unknown and the public received no information regarding their opinions or ideas. Some of the rezoning dissenters who had appealed the Planning Board’s decision galvanized an existing group in the District to consider moving in a different direction. Believing they had been excluded from outreach efforts to engage in plans for the District, the group coalesced around rejecting the FSA-MUD. They held at least one meeting in the Alamo Theater to express their ideas, some of which mirrored the basics tenets of the FSA-MUD. One appellant, a longtime advocate for historic Farish Street, remains a strong supporter for preservation of the area.

6.3. Lessons Learned: Setbacks and Advancements

While trying to move the group and the process from malaise to action, several issues surfaced in the form of concerns and resistance to moving forward on the proposal. Divergent opinions regarding the benefits of retaining the historic district status emerged. One particular discussion focused upon delisting the District from the National Register. Reasons provided by meeting participants who supported delisting held the view that trying to adhere to the preservation guidelines for restoration, updating and making changes would prove too cumbersome and expensive.

Given the resistance that the proposed rezoning met as stated in the appeals, one could restate the arguments that citizen involvement, however controversial, should be as inclusive as possible. Planning theorists such as John Forester [30] and public participation advocates such as Paul Davidoff [31,32]; Sherry Arnstein [8]; Judith Innes [33], Delores Hayden [34] and John Friedmann [35] provided insight into the significance of citizen empowerment. They underscored the importance of public participation in deliberative public participation in deliberative and decision-making processes. Forester [30,36,37] in particular cautioned that abiding questions “must inform decisions—questions that address inclusion and meaningful participation.

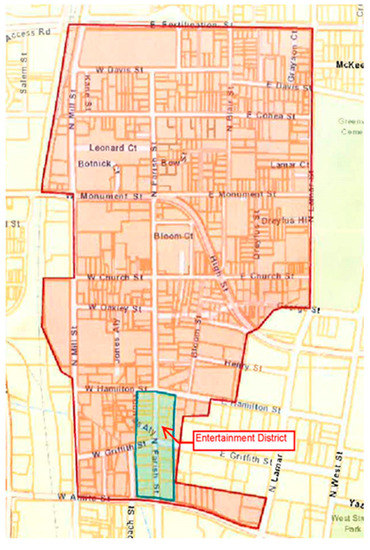

Although the appellants may not have agreed with the proposed rezoning, they may have been more inclined to accept the proposed rezoning land use plan had they felt they had been given the opportunity to have their concerns addressed and questions answered prior to submission to the City Planning Board. The fate of the Farish Street Historic District is currently unknown and little progress has been made in the past decade. Development of an entertainment district held a lot of promise for the area and received enthusiastic reception (Figure 6). However, with the exception of a couple of popular venues, that too remains an unrealized idea.

Figure 6.

Entertainment District. Source: Department of Planning & Development Zoning Division, Jackson, MS.

6.4. Advancements

In spite of the bleak outlook for the Farish Street Historic District, minute changes have occurred. An 88 unit townhome affordable housing initiative, Helm Place, named for Mount Helm Baptist Church, an old historic church located in the District [38]. The Scott Ford houses located on Cohea Street in the District were recently targeted for preservation [39]. The houses date back to 1891–1892. They belonged to Mary Green Scott, a former slave and Virginia and John Ford. Virginia Ford, Mary’s daughter, was a practicing midwife for 40 years. They were among the first African Americans to develop their homes on Cohea Street. The Fords and their descendants owned the property for over a century [39,40]. Plans are underway to restore the homes and make it a museum to tell the story of midwifery. In August 2018, the Jackson City Council voted to allow a developer based in Oxford, Mississippi to receive seven parcels targeted for housing development near Helm Place [41].

7. Conclusions

According to Blakley [42], participation in community and public meetings generally remains an activity in which only a minority of players engage. Stakeholder participation in efforts to develop rezoning for the Farish Street Historic District was uneven. Although participation was encouraged and garnering support crucial to develop a strategy to improve conditions in the District, full involvement did not occur and enthusiasm was tempered. Only a small number of property holders and descendants of early Farish Street attend meetings. The now defunct Farish Street Neighborhood Association offered no additional pathways for expanding participation. Further, a small and informal but tightly structured group that later became appellants to the Planning Board approved proposal complained they were not actively sought out to participate in community meetings.

Whether engaging in participatory processes to discuss issues relevant to regeneration, sustainability, or land-use, Forester [43] maintains that the concept of participation remains ambiguous. Further, in order to obtain optimal public participation, Arthurson posits [44] that stakeholders must be given sufficient time to engage in deliberative processes. These issues may have factored into the less than desirable outcome for the proposed rezoning for the Farish Street Historic District. Interested stakeholders maintain a cautious optimism that the issue is not dead, only taking a reprieve from the flurry of intense public engagement. Development remains sluggish and occasional, occurring every few years. Yet, significant improvements in the Central Business District should make Farish Street more attractive to investors. These slow and intermittent successes invite renewed interest in the District. Finally, the collaborating architects of the FSA-MUD are poised to revisit the plan, engage planning students in another round of area stakeholder participation, update the document where indicated and present it to the current Administration.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed substantially to this study, including data collection and analysis, and final write-up. Conceptualization, J.M.W. and E.L.A.; Data curation, J.M.W. and E.L.A.; Investigation, J.M.W. and E.L.A.; Methodology, J.M.W. and E.L.A.; Project administration, J.M.W. and E.L.A.; Supervision, J.M.W.; Writing—original draft, J.M.W.; Writing—review and editing, J.M.W. and E.L.A.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ashley Conish, Assistant to the Land Use Planning Manager and students from the Neighborhood/Urban Revitalization Studio for their contributions to the Farish Street Project: Valerie Purry, Jamie Jones, Sherita Jones, Claudette Jones, Ercilla Dometz Hendrix, Latoya Kitchens, Von Anderson, Pamela Daniel

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form; United States Department of the Interior National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 13 March 1980.

- Bonds, M.; Farmer-Hinton, R.L. Empowering neighborhoods via increased citizen participation or a Trojan horse from city hall: The neighborhood strategic planning (NSP) process in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 2009, 13, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Are collaboration and participation more trouble than they’re worth? Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.; Smith, S.N.; Ostergren, G. (Eds.) Consensus Building, Negotiation, and Conflict Resolution for Heritage Place Management. In Proceedings of the Workshop Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1–3 December 2009; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jones, D. The impact of trust (or lack thereof) on citizen involvement. Natl. Civ. Rev. 2010, 99, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginn, P.J. Towards a more effective community participation in urban regeneration: The potential of collaborative planning and applied ethnography. Qual. Res. 2007, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Regeneration and community involvement. City 2003, 7, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. Am. Inst. Plan. J. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E. A ladder of empowerment. J. Plan. Edu. Res. 1997, 17, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Rethinking sustainable urban regeneration. Ambiguity, creativity, and the shared territory. Environ. Plan. 2008, 40, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. On the social nature of planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson. 2009. Available online: http://www.visitjackson.com/ (accessed on 27 July 2018).

- Miles, D.G. From Frontier Capital to Modern City: A History of Jackson, Mississippi’s Built Environment, 1865–1950; Jaeger Co.: Gainesville, GA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen, N.R. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Suburbanstate.org. Population Demographics for Jackson, Mississippi 2017, 2018. Available online: https://suburbanstats.org/population/mississippi/how-many-people-live-in-jackson (accessed on 27 July 2018).

- Farish Street Historic District and the Farish Street Heritage Festival History. Available online: http://www.farishstreetheritagefestival.com/history/ (accessed on 25 July 2018).

- Mississippi Heritage Trust. (n.d.) “Farish Street Historic District”. Available online: http://www.ms10most.com/listing/farish-street-historic-district/ (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Design Guidelines for the Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District; Winter & Company: Jackson, MS, USA, 2000.

- Harrison, A. The importance of the Farish Street Historic District. In The Farish Street Historic District: Memories, Perceptions, and Developmental Alternatives (A Selection of Essays and Statements); Jackson State University, Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People: Jackson, MS, USA, 1983; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe, S. Guiding Additions to Historic Properties: A Study of Design Guidelines for Additions in Sixty-Five American Cities. Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp theses/48 (accessed on 3 June 2010).

- Tate, B. Old House, New Future: The Quiet Revival of the Shotgun House. Master’s Thesis, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, M. A cultural sketch of Farish Street. In The Farish Street Historic District: Memories, Perceptions, and Developmental Alternatives (A Selection of Essays and Statements); Jackson State University, Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People: Jackson, MS, USA, 1983; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.N. Farish Street: The way it was. In The Farish Street Historic District: Memories, Perceptions, and Developmental Alternatives (A Selection of Essays and Statements); Jackson State University, Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People: Jackson, MS, USA, 1983; pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Holly, K.W. Reflections of a historical street. In The Farish Street Historic District: Memories, Perceptions, and Developmental Alternatives (A Selection of Essays and Statements); Jackson State University, Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People: Jackson, MS, USA, 1983; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rypkema, D. Historic Preservation and Affordable Housing: The Missed Connection. National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2002. Available online: http://www.placeeconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/placeeconomicspub2003b.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2009).

- Lynch, A. Old wound still bleeds on Farish. Jackson Free Press. 25 June 2008. Available online: www.jacksonfreepress.com (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Arefi, M. Non-place and placelessness as narratives of loss: Rethinking the notion of place. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, R. 21st Century Black Studies: Digital Publications. In The Farish Street Area Mixed Use District. Purpose of the District: Mississippi’s Little Harlem (A Selection of Essays and Statements); Jackson State University, Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People: Jackson, MS, USA, 2015; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- City Council Agenda. Zoning Cases to Be Considered by the City Council; City Council Agenda: Atlanta, GA, USA, 20 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and pluralism in planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1965, 31, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, P. Working toward redistributive justice. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1975, 41, 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J. Group Processes and the social construction of growth management: Florida, Vermont, and New Jersey. In Explorations in Planning Theory; Mandelbaum, S., Mazza, L., Burchell, R., Eds.; Center for Urban Research, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, D. Who plans the USA? A comment on advocacy and pluralism in planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1994, 60, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning in the Public Domain; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Planning in the Face of Power; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Making participation work when interests conflict. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, J.E. Housing Transformation in Farish Street Historical District. The Clarion-Ledger. 19 June 2015, p. 1. Available online: https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2015/06/19/housing-transformation-farish-street-historical-district/29015405/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- The Scott Ford Houses—Rescuing Jackson Mississippi’s Midwife Family Homes & Stories of African American Midwifery. Available online: https://www.scottfordhouse.com/ (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Bragg, K. A Midwife’s Tale: Saving the Scott Ford Houses; Jackson Free Press: Jackson, MS, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2017/nov/08/midwifes-tale-saving-scott-ford-houses/ (accessed on 18 July 2018).

- Bragg, K. Developer Secures More Farish Properties; Area Blight Worries Council. Available online: http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2018/aug/15/developer-secures-more-farish-properties-area-blig/ (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Blakeley, G. Who participates, how and why in urban regeneration projects? The case of the new city of East Manchester. Soc. Policy Adm. 2009, 43, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Interface. Practice challenging theory in community planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Arthurson, K. Neighborhood regeneration: Facilitating community involvement. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).