Abstract

Tourism governance evaluates the participation of stakeholders in planning and development decisions within a territory. Understanding who these stakeholders are and their involvement is crucial, as tourism impacts social, economic, and cultural spaces, requiring equitable distribution of its costs and benefits to ensure sustainability. This study focuses on the UNESCO Environmental Corridor of Extremadura, using data from the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura and visitor surveys to define its tourist scope. A literature review identified dimensions and variables of tourism governance, leading to the design of questionnaires and evaluation scales, as well as the identification of stakeholders based on existing research. Results reveal variability in tourism governance across territories, with a notable lack of management concerning gender and functional diversity. While aligning with existing literature on the underdevelopment of shared governance policies, the study highlights progress in stakeholder participation strategies, particularly in territories with UNESCO designations. The UEC territories stand out for their strategic tourism development plans, stakeholder consultation, sector coordination, and diverse participatory decision-making mechanisms.

1. Introduction

In the current context, there is an increasingly frequent backlash against tourism development in certain destinations due to overcrowding and the lack of a genuine culture of participation in decision-making processes affecting residents [1]. Tourism governance involves considering the level of stakeholder participation in decisions related to tourism planning and development in a given territory. This line of thought advocates for establishing mechanisms that enable the participation of all interested parties who “engage with” or are “impacted by” tourism. In this participatory decision-making strategy, it is essential to incorporate broader interests and values, such as preventing the abuse of power and enhancing accountability and transparency in actions taken [2]. Moreover, it is crucial to identify who these stakeholders are and their level of involvement in the decision-making process. Tourism is a phenomenon that tends to expand, occupying social, economic, and cultural spaces that affect the resident population. Therefore, the distribution of the costs and benefits associated with its development must be shared among stakeholders to ensure its sustainability [3]. Tourism impacts multiple sectors, fostering tax revenue generation and the formalization of small businesses in the communities where it is established. This industry drives local economic growth and becomes a key factor in poverty reduction by promoting various activities that strengthen the economy of companies engaged in the production and supply of goods and services for visitors [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly detrimental to the tourism sector, which faced significant challenges due to border closures, travel restrictions, and a consequent decline in visitors. These factors led to the closure of numerous businesses due to a lack of customers. In response to this reality, efforts have been made to revitalize tourism with a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable approach [5]. However, opinions on the future of the sector vary widely and lack a clear consensus, as each party defends its own perspective. In this context, rather than engaging in debates without a common direction, it is essential to foster cooperation and synergy to strengthen the sector’s development and create innovative products that serve as benchmarks for the tourism industry [6].

Regarding governance, it is a term that comes from the English language and began to be used in Europe in the 1980s. Its initial purpose was to improve public policy management by facilitating government intervention and streamlining decision-making, particularly in economic matters [7,8]. Today, governance is considered a key element in tourism development, as collaboration between the public sector, private sector, and civil society can stimulate this activity [9] and strengthen local institutions. This collaboration helps reduce both economic and social costs [10], and promotes greater equity among stakeholders, as well as increased consensus and effective participation guaranteed by governments [11].

In this sense, tourism governance advocates for the establishment of participation mechanisms in decision-making processes that take into account the inclusion of all interests [12], which involves identifying the tourism stakeholders. In the early 1990s, the literature primarily identified two groups of potential actors as stakeholders in tourism management: the economic interest group—the private sector—and the public interest group—represented by the public tourism authority, such as ministries, departments, etc. [13,14]. Later, the range of stakeholders expanded to include other groups such as local users, scientists, professionals and experts, as well as non-governmental organizations, including neighborhood, citizen, civic, and cultural associations [15]. For instance, González highlights the importance of involving key stakeholders in a tourist destination, such as the state, public and private organizations, civil society, and the local population. When these actors work in a coordinated manner with a shared objective, they can significantly contribute to the development of tourism in the region [16].

Consequently, governance is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve such development. Following Valdivia and Armesto, governance can be understood as the set of norms, principles, and values that regulate the interaction between the various actors involved in the formulation and implementation of public policies. However, its effectiveness depends on an analysis that considers both the actions and the discourses that shape it. Therefore, it is essential to create spaces that encourage greater participation of local actors in tourism activities. This requires examining how governance has developed so far, understanding the dynamics among stakeholders, and evaluating the approaches applied. In this way, it will be possible to design more effective strategies that can be implemented and analyzed within the most appropriate methodological frameworks [17].

The development of participatory governance models in the so-called UNESCO Environmental Corridor—hereafter, UEC—of Extremadura represents examples of good practices that should be studied and valued, as well as analyzed for their deficiencies and areas for improvement; an endeavor we aim to pursue in this article.

The aim of this study is to understand the dynamics of tourism governance in the four territories that make up the UNESCO Environmental Corridor (UEC) of Extremadura, starting from their tourism dimensions.

The UEC of Extremadura includes the territories of the Villuercas-Ibores-Jara World Geopark, which encompasses the Royal Monastery of Guadalupe, the La Siberia Biosphere Reserve, the Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve, and the Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, which was one of the Destination Cohesion Actions (ACD) within the 2021–2023 Tourism Sustainability Plan of Extremadura. At the time, the goal set by the regional government was to «create a nature destination with projects dedicated to environmental restoration and energy efficiency measures for public tourism camps, the enhancement of the ‘Water Ark of Guadalupe’, the creation of the UNESCO Extremadura Digital Tour, as well as the design of tourist itineraries with relevant information necessary for travel organisation» [18]. Furthermore, the objective of these public sector initiatives was to address the environmental, economic, and social sustainability challenges of the region, proposing actions in tourist destinations and flagship projects for cohesion between destinations in the fields of green transition, digital transition, and tourism competitiveness [18].

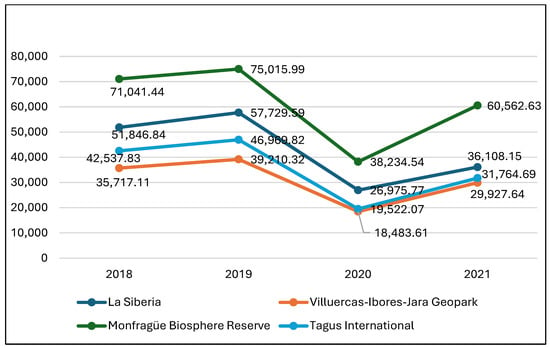

The tourism demand for the UEC reached 158,364 visitors in 2021, accounting for 11.7% of the 1352,175 tourists who visited Extremadura that year considering that at that time, the effects of demand restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic were still present. In 2019, for example, the tourist flow reached 1900,000 visitors [19]. Of the four territories within the UEC, the Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve is the most visited, with around 60,000 visitors annually—75,000 before the pandemic.

The analysis of the flow of travelers to the UEC territories and its evolution from 2018 to 2021 shows significant variations, mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Mobility restrictions and the temporary closure of many tourism-related activities significantly affected tourism. The decline was more pronounced in territories with lower tourist inflow, such as the Tagus International and the Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark.

Acording with Table 1, in 2021, the territories began to recover part of the tourist flow lost in 2020. Although none of the territories returned to 2019 levels, the recovery was significant. The Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve showed a notable recovery, reaching 80.75% of its 2019 level. The recovery was less pronounced in La Siberia, La Serena, La Campiña Sur, and Tagus Internacional, Sierra de San Pedro, with recoveries of approximately 62.54% and 67.60%, respectively, compared to 2019 levels.

Table 1.

Passenger flows to the UEC territories. Evolution 2018–2021.

Table 1.

Passenger flows to the UEC territories. Evolution 2018–2021.

| Tourist Territories, to Which the Counties of the UEC are Attached | Travellers 2018 | Travellers 2019 | Travellers 2020 | Travellers 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve | 71,041 | 75,016 | 38,235 | 60,563 |

| La Siberia, La Serena, Campiña Sur * | 51,847 | 57,730 | 26,976 | 36,108 |

| Tagus International, San Pedro Mountains * | 42,538 | 46,970 | 19,522 | 31,765 |

| Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark | 35,717 | 39,210 | 18,484 | 29,928 |

| Total Extremadura | 1,866,168 | 1,938,233 | 844,604 | 1,352,175 |

* The available statistical information does not allow disaggregating data for this UEC demarcation. Source: Prepared by the authors based on the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura [19].

The following graph (Figure 1) represents the evolution of the flow of tourists in the four territories of the UEC of Extremadura, including their counties in the observed period from 2018 to 2021.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the number of tourists in the UEC territories, 2018–2021. Source: Prepared by the authors based on the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura [19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Contex of the Study: Extremadura’s UEC Area and the Administrative Characterisation of Its Territories

The UNESCO Environmental Corridor of Extremadura, as mentioned above, covers the territories of the Biosphere Reserve of La Siberia, the Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Global Geopark, the Biosphere Reserve of Monfragüe, the Transboundary Biosphere Reserve Tagus-Tejo International, as well as the Royal Monastery of Guadalupe. This corridor is made up of more than 910,803 hectares, 58 municipalities, and more than 50,000 inhabitants [20].

Spain is divided into autonomous communities, which are first-level political and administrative regions. Extremadura is one of these autonomous communities, located in the southwest of the country. Within Extremadura, the so-called UNESCO Environmental Corridor (UEC) is composed of four environmentally protected areas that do not correspond to administrative divisions, but rather to functional territories with special designations—such as Biosphere Reserves or a UNESCO Global Geopark. In this study, we refer to these territorial units as “UEC territories” or “territories of the Corridor” to distinguish them clearly from the broader autonomous community of Extremadura.

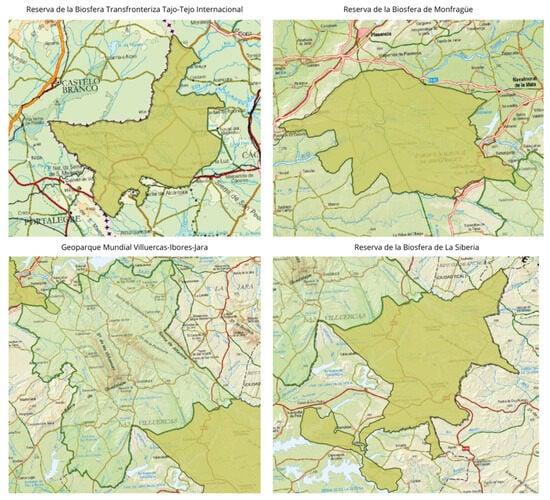

This Spanish region is located in the south-west of the country, bordering Portugal on its western side. Therefore, the study focuses on the four territories mentioned above, which are practically connected geographically, forming what is known as the UNESCO Environmental Corridor (Figure 2 and Figure 3). One of the four territories, the Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve covers its space in the two provinces of Extremadura (Cáceres and Badajoz) and Portugal; the following two territories belong entirely to the province of Cáceres: Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara World Geopark; and the last territory, La Siberia Biosphere Reserve, is located east of the province of Badajoz bordering the province of Cáceres (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Counties over which the territories of the UEC in Extremadura are spread. Source: Own elaboration from https://redex.org/informacion-territorial (accessed on 12 March 2025).

Figure 3.

The four UEC territories in Extremadura. Source: Own elaboration from https://astrocaceres.com/el-territorio/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

Figure 4.

Situation of the UEC territories in Extremadura and its provinces with bordering limits. Source: Own elaboration adapted from https://redex.org/informacion-territorial and https://www.minube.com/tips/actualidad/extremadura-naturaleza-birding-grullas-astroturismo (accessed on 20 March 2025).

Figure 5.

Individual maps of each UEC territory. Source: Own elaboration adapted from [21,22].

These areas are part of the Network of Protected Natural Spaces of Extremadura (NPNSEX). According to the Law on Nature Conservation and Natural Spaces of Extremadura, “Protected Natural Areas” are regions within the Autonomous Community of Extremadura that are declared as such under the law, based on the representativeness, uniqueness, rarity, fragility, or significance of their natural elements or systems. For these areas, within the framework of sustainable development, appropriate protection and conservation regimes will be implemented for both their biological diversity and the associated natural and cultural resources. Elements of the Natural Heritage of Extremadura that are declared or considered under this law will be given the same consideration. The protection of these areas may be based, among other things, on the following objectives: To create a representative network of the main ecosystems and natural regions in the Autonomous Community; To protect areas and natural elements that offer singular interest from scientific, cultural, educational, aesthetic, landscape, and recreational perspectives; To contribute to the survival of communities or species in need of protection by conserving their habitats; To collaborate in international programs for the conservation of natural spaces and wildlife that affect the Autonomous Community [23,24,25,26,27,28].

In the Protected Natural Areas of Extremadura, sectoral regulations will be subordinated to the conservation objective as determined in the planning instruments defined by this law. The types of these areas are: Natural Parks, Nature Reserves, Natural Monuments, Protected Landscapes, Areas of Regional Interest (ZIR), Ecological and Biodiversity Corridors, Peri-urban Parks for Conservation and Leisure, Sites of Scientific Interest, Singular Trees, and Eco-cultural Corridors [20].

Private Areas of Ecological Interest: To complement public actions on biodiversity protection and contribute to the conservation of natural areas with special ecological or landscape significance, any individual or legal entity may request the relevant authorities, in accordance with the legal provisions, to establish an area of ecological interest on land they own, or land owned by a third party, if they have the appropriate authorization. The declaration of these areas will involve the establishment of a regime that ensures the compatibility of land uses with the conservation objectives [20].

Transboundary Protected Natural Areas: Transboundary protected natural areas may be established through international agreements between the relevant states. For the purposes of the aforementioned law, areas specifically dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity and the associated natural and cultural resources that are integrated, at a minimum, by a Protected Natural Area established in accordance with the provisions of this law and an adjacent natural area, located in the national territory that shares a border with Extremadura and is subject to a special legal regime for biodiversity conservation, will have this consideration [29,30].

In Table 2, all the information on the administrative characterization of the four CMU territories in Extremadura can be consulted.

Table 2.

Administrative characterization of the UEC territories.

Table 2.

Administrative characterization of the UEC territories.

| Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve | Monfragüe National Park and Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve | La Siberia Biosphere Reserve | Villuercas-Ibores-Jara UNESCO World Geopark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of declaration | 18 March 2016 | 9 July 2003 | 19 June 2019 | September 2011 |

| Surface area | 260,267.06 ha. in Spain and 168,533 ha. in Portugal | 116,161.80 ha | 155,380.82 ha | 2544 km2 |

| Location | Extremadura (Spain) and Portugal | Province of Cáceres. Autonomous Community of Extremadura | North-east of the province of Badajoz in the Guadiana basin | South-east of the province of Cáceres, between the basins of the Tagus and Guadiana rivers |

| Municipalities | 14 Extremadura municipalities and 12 Portuguese parishes | 14 (3 of them fully integrated in the Reserve) | Castilblanco, Fuenlabrada de los Montes, Garbayuela, Helechosa de los Montes, Herrera del Duque, Puebla de Alcocer, Risco, Sancti-Spíritus, Tamurejo, Valdecaballeros y Villarta de los Montes | 19 municipalities and 8 districts. The 14th century Royal Monastery of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (World Heritage Site 1993) is located in this area |

| Population | 62,775 inhabitants (Spain 14,325 inhabitants; Portugal 48,450 inhabitants) | 2882 inhabitants | 11,233 inhabitants | 12,455 inhabitants |

| Other forms of protection |

| + National Park + Site of Community Importance (SCI)1. + Special Areas of Conservation (SAC). + Special Protection Area for Birds (SPA). Biogeographical region/province: Mediterranean | Zone of Regional Interest: Orellana Reservoir and Sierra de Pela Four Special Protection Areas for Birds (SPA). Six Special Areas of Conservation (SAC). RAMSAR Site—Orellana Reservoir. Ecological and Biodiversity Corridor Guadalupejo River. | Seven Special Protection Areas for Birds (SPA) and eight Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) Sites of Community Importance (SCI) recognised under the EU Habitats Directive. |

| Management Entity | Regional Government of Extremadura. Regional Ministry of Environment and Rural, Agricultural Policies and Territory. Dirección General de Medio Ambiente (Spain). Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests (Portugal) | Autonomous Community of Extremadura, through the competent Regional Minister for the Environment and the Director General in charge of Protected Areas | Badajoz Provincial Council | Autonomous Community of Extremadura, through the competent Regional Minister for the Environment and the Director General in charge of Protected Areas. |

Source: Own elaboration based on [20,31].

2.2. Objective, Study Strategy, and Applied Methodologies

Our aim is to identify the patterns of tourism governance in the territories within the UNESCO Environmental Corridor (UEC) based on the tourism reality of the area.

To achieve this objective, we conducted a bibliographic and documentary review and studied existing secondary data on this territory. It was deemed necessary to undertake a contextual approach to the territories within this area in order to gain an overview of the UEC and thus move towards the creation of an integrated and identifiable “destination”, not only from a tourism perspective, but also in terms of its economic, demographic, and social dimensions. We relied on various sources, the main one being the Institute of Statistics of Extremadura through its Sociodemographic Atlas [32]. This information poses the challenge of being not aggregated territorially, but rather being dispersed, and in some cases, it was necessary to group municipalities together to better understand the reality of the subsets that make up the UEC.

We also analyze tourism demand, particularly in recent years, using a quantitative methodology, by conducting a survey with tourists on the ground. We examine their motivations and how they organize their trips, accommodation patterns, overnight stays, information sources, their connection to the destination, the activities they engage in, and their assessments of the tourism offerings, resources, hospitality, and professionalism.

To analyse the tourism governance processes, we used a qualitative methodology by holding four focus groups where rating scales were applied to the participants during November 2022. This allowed us to systematize the discursive contribution regarding the reality of the analyzed areas.

2.3. Survey of Tourists That Visit the Territory

To characterize the tourists visiting the territory, surveys were conducted in the four UNESCO territories. The total sample size (n) was 406 surveys, divided across the four areas of the EMC, as reflected in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sample allocated to each UEC area.

Table 3.

Sample allocated to each UEC area.

| UNESCO Environmental Corridor Area | Surveys Conducted |

|---|---|

| Villuercas-Ibores-Jara UNESCO World Geopark | 105 |

| La Siberia Biosphere Reserve | 100 |

| Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve | 101 |

| Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve | 100 |

| Total | 406 |

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Study on the Environmental Corridor of Extremadura. University of Extremadura. Agreement for the generation of tourism knowledge 2022 [20].

Statistical Values. A stratified random sampling method is conducted based on the four territories, with quotas for gender and age [33] (pp. 132–151). In 2021, we established a population universe of N = 158,364 tourists across the four territories, which allows for a sample size of n = 406. This corresponds to a 95% confidence level and a statistical error of ±4.9% under conditions of maximum variability, i.e., p = q = 0.5. The formula for infinite populations (more than 100,000 subjects in the population universe) is as follows [34] (pp. 93 et seq.):

Statistical Errors in Disaggregated Values. Assuming a simple random sampling method, the sampling error increases as the number of responses decrease [35,36]. This is particularly relevant when variables are cross-tabulated, for instance, in the case of territories. As a reference, under the assumption of simple random sampling, p = Q = 1/2, and a 95% confidence level (CL), the sampling errors are as follows (Table 4):

Table 4.

Sampling errors and number of responses.

Table 4.

Sampling errors and number of responses.

| No. of Surveys | 5 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 500 | 750 | 1000 | 1500 | 2000 | 2500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling error ± (%) | 44.7 | 31.6 | 22.4 | 14.1 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on reports from the Sociological Research Centre (CIS) [37].

Other characteristics of the sampling data sheet were:

Survey Period: June-October 2022.

Quotas: Age and Gender.

Segmentation Variables: Area of the Environmental Corridor.

Data Analysis Type: Descriptive and interpretative analysis of the information provided by the tables. The explanatory (causal) study is reserved for later lines of research).

2.4. Focus Groups

To complement the information from the survey data of visitors to the four territories of the UEC, it was considered necessary to discuss and gather the informed opinions of the stakeholders from the four areas [38]. To this end, four focus groups were conducted in Alcántara, Torrejón el Rubio, Herrera del Duque, and Cañamero, during November 2022. A total of 18 informants participated in these groups, and a rating scale was applied, which was completed by 12 individuals.

The reliability analysis of the rating scale included in the form gives a value of 0.842 (Cronbach’s alpha), which is sufficient to consider the tool as acceptable for these purposes.

The identification and selection of local stakeholders for the research was based on the work of Palmer and Bejou [39] and Greenwood [40], who consider two groups of potential actors as stakeholders in tourism management: the economic interest group (private sector) and the public interest group (represented by the public tourism agency, such as secretariats, departments, etc.). However, Caffyn and Jobbins [41] broaden the constituent components of ‘stakeholders’ in tourism, for example, research on integrated coastal zone management incorporated local users, scientists and non-governmental organizations. Research from 2000 onwards also considers residents. Our panel identified 82 people who could be included in these stakeholders, all of whom were invited to participate in the different sessions distributed territorially in the four territorial districts, but only 18 people were actively involved. Motivation to take part in this dynamic was low, despite activating some incentives such as using the logistics of hotels and/or restaurants that are well valued in the zones, repeatedly insisting on invitations through external ‘contactors’, and appealing to relevant actors in the zones, such as mayors and other leaders. Nevertheless, we consider that the contributions of these participants were very relevant and illustrative of the socially shared discourse on tourism governance. Table 5 presents the characteristics of each of the focus groups.

During these sessions, preliminary information from the research carried out throughout the year was presented, and the informed opinions of the participants were sought. These opinions were recorded in audio format and processed for subsequent analysis [38,42].

Table 5.

Characteristics of the focus groups.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the focus groups.

| Focus Groups | Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve | Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve | Villuercas-Ibores-Jara UNESCO World Geopark | La Siberia Biosphere Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place of celebration | Alcántara (Hospedería Conventual de Alcántara) | Torrejón el Rubio (Hospedería de Monfragüe) | Cañamero (Casa Rural La Brizna) | Herrara del Duque (Hostal Resta Paco’s) |

| Date Duration | 15/11/2022 Duration: 92’ | 17/11/2022 Duration: 120’ | 22/11/2022 Duration: 125’ | 24/11/2022 Duration: 120’ |

| Participating typologies | Five people are participating. Three of them are women Two of them are experts, tourist informants. Two of them are entrepreneurs of the hotel and catering industry in the area. One more person is a tourism technician of the Provincial Council of Cáceres. | Three people participate. Two of them women. An entrepreneur of tourist activities, a municipal technician and the technician of the Provincial Council of Cáceres. | Five social actors of the territory participate: 1 woman and 4 men: two businessmen, a mayor and two technicians of the Provincial Council of Cáceres. In addition, the Director General of Tourism of the Junta de Extremadura and two researchers from the UEX team also participate. | Five social actors are involved: four are women and one is a man. Two of them are tourism technicians from the local councils. Three of them are entrepreneurs of rural houses. |

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Study on the Environmental Corridor of Extremadura. University of Extremadura. Agreement for the generation of tourism knowledge 2022 [43].

3. Results

3.1. Characterisation of Tourism Demand in the UEC Based on the Surveys Carried Out

The 406 validated surveys make it possible to qualify tourism demand and to analyze, in the four areas of the UEC, different aspects of the tourism behavior of the people who visit it. These aspects include the reasons for visiting this destination, the way the trip is organized, the accommodation choices, the number of overnight stays, where they obtain information to decide to visit this destination, their connection to the destination, the activities they engage in, and an evaluation of the tourist offerings in the four analyzed territories2.

The main reason for visiting the environmental corridor is to visit natural spaces and go hiking, especially in the Monfragüe Reserve, where more than 60% of respondents visit for this reason. It is also worth noting that 23% of the respondents who visit the La Siberia Reserve do so to visit family and friends.

The majority of respondents, more than 75%, choose the UNESCO Corridor as a travel destination, particularly those from the Villuercas Geopark and the La Siberia Reserve. It is also noteworthy that in the case of Monfragüe, 42.6% of respondents visit with the purpose of going to another town in the region; therefore, these are purpose-driven trips.

According to the surveys, when organizing their trips to these areas, most respondents—over 37%—prefer to organize the trip with family, although organizing the trip with a partner follows closely at 31%. It is noteworthy that the most chosen option in the case of the Villuercas Geopark is organizing the trip in a group, at 31.7%, which differs from what happens in the other three areas of the Corridor.

When asked about the means of transportation used to reach the UEC, there is a clear preference for cars, with an average of more than 71% across the four areas, reaching up to 76% in the case of the Villuercas Geopark. However, it is worth highlighting, particularly in the La Siberia area, that vehicles such as caravans, motorhomes, or camper vans are a second option, with these being the preferred vehicle for nearly 20% of respondents in the mentioned area.

As for preferred types of accommodation, rural lodging stands out in three of the four selected areas, ranging from 18% to 26%. However, this is not the case in the Tagus Internacional Reserve, where 11% of respondents prefer staying at a family member’s or friend’s home when overnighting.

It is important to analyze the average number of nights respondents stay. In three of the four areas of the Corridor, respondents stay on average more than two nights, approaching two and a half nights, especially in the Villuercas Geopark with an average of 2.46 nights and in the La Siberia Reserve with 2.43 nights on average. However, the Tagus Internacional Reserve is notable for having the lowest average stay, barely exceeding one and a half nights. This area also stands out for having the lowest variability, with a standard deviation of 0.69, while in Villuercas and La Siberia, the standard deviation ranges between 1.7 and 1.9, and in Monfragüe, it is around 1.2. The most chosen accommodation option is “room only”, with a clear preference over the second most chosen option—”bed and breakfast”—in three of the four areas of the Corridor; except for Tagus Internacional, where the preference is more evenly distributed across all options.

Regarding the information medium used to learn about the tourist destinations of the UNESCO Environmental Corridor, we note that the most relevant medium is “family and friends,” particularly emphasized in the case of La Siberia, where approximately 60% of respondents obtain information through this channel.

It is also important to highlight “Internet” as the usual information source, as well as emphasize the importance of “recommendations from close people” to the visitors. Notably, 63% of respondents claim to have no connection to the UNESCO Corridor, but it should be mentioned that a high percentage of people feel connected to these areas due to having family and friends in nearby towns, especially in the La Siberia Reserve, where nearly 40% of respondents relate to the corridor for this reason.

Word clouds help understand the specific characteristics and attractions of each territory, highlighting their main tourist offerings and the aspects considered most important by visitors and promoters. The inputs in Atlas’ti for this descriptive-analytical procedure were the discourses collected by the participants in the focus groups carried out in each of the four territories, as can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Clouds of mentions about activities carried out by tourists according to UEC territories. In brackets is the range of mentions from 1 to 177 mentions. Source: Prepared by the authors based on the opinions gathered in the focus groups carried out for the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura [20].

The word clouds presented in the image reflect the most prominent words in the perception and promotion of tourism in these areas, according to the survey respondents. Each word cloud highlights terms that are most relevant or frequently associated with each tourist territory.

- Villuercas-Ibores-Jara World Geopark. Key words:

Visit: Suggests an active invitation to explore this area.

Spaces: Indicates the importance of open natural spaces.

Natural: Highlights the value of natural resources.

Hiking: A popular activity in the region.

Heritage: Indicates historical and cultural richness.

Cultural, Historic-Artistic, Tasting: Emphasizes cultural and gastronomic offerings.

- 2.

- La Siberia Biosphere Reserve. Key words:

Visit: Again, an invitation to explore the region.

Spaces: Importance of open spaces.

Natural: Appreciation of natural resources.

Hiking: An important activity.

Heritage, Cultural, Historic-Artistic: Emphasizes historical and cultural richness.

Gastronomic, Tasting: Significance of gastronomic offerings.

Family: Suggests the destination is suitable for families.

Sports activities: Offers of sports activities.

- 3.

- Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve. Key words:

Visit: Promotion of visiting the region.

Spaces: Highlights the importance of open spaces.

Natural: Value of natural resources.

Hiking: A key activity.

Heritage, Cultural, Historic-Artistic: Emphasizes historical and cultural richness.

Tasting, Gastronomic: Importance of gastronomic offerings.

Birdwatching: Indicates the popularity of birdwatching, a characteristic activity of Monfragüe.

- 4.

- Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. Key words:

Visit: Invitation to explore the region.

Spaces: Importance of open spaces.

Natural: Value of natural resources.

Hiking: A popular activity.

Heritage, Cultural, Historic-Artistic: Emphasis on historical and cultural richness.

Tasting, Gastronomic: Relevance of gastronomic offerings.

Explore: Promotes active exploration of the region.

Birdwatching: Similar to Monfragüe, highlighting the popularity of birdwatching.

In general, the most common words across the four territories are: “visit”, “spaces”, “natural”, “hiking”, “heritage”, “cultural”, “historic-artistic”, “tasting”, and “gastronomic”. These common words suggest that all the territories share a focus on inviting people to visit, appreciating natural spaces, hiking activities, historical and cultural richness, and gastronomic offerings.

The main differences are:

- Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark: A greater focus on “cultural” and “sports”.

- La Siberia: Focus on “family” and “sports activities”.

- Monfragüe: Emphasis on “birdwatching”.

- Tagus-Tejo International: Similar to Monfragüe with a focus on “birdwatching” and “explore”.

If we analyze the data collected from the surveys, we can observe that the vast majority, over 90% of respondents, did not book any activities through a company within the UNESCO Corridor areas. The only notable exception is the Villuercas Geopark, where 11.5% of respondents booked activities through a company.

Focusing on the evaluation of infrastructure services, we highlight that the access signage and tourism infrastructure are the best-rated, with a score of 4.3 in both cases. The local gastronomy is also highly rated, with 4.75 out of 5. Regarding the assessment of heritage conservation, the Villuercas Geopark holds the highest position, with an average score of 4.46, closely followed by Monfragüe and Tagus with an average of 4.43 in both territories. Monfragüe has the best rating for the natural environment and signage, with an average of 4.7, while the other areas of the Corridor all have similar averages around 4.6.

If we focus on the dispersion of ratings, two notable figures stand out. First, there is a significantly lower standard deviation for the rating of territory conservation, where the Tagus Transboundary Reserve has a standard deviation of 0.47. The second case is observed in the rating of local gastronomy, with a much higher standard deviation for the Monfragüe Reserve (0.74) compared to the other areas of the Corridor, where it is around 0.5. When analyzing the professionalism of staff and the hospitality and friendliness of the population, we observe that for professionalism, the average is very similar across the four areas, hovering around 4.4. On the other hand, the average rating for hospitality and friendliness is around 4.5 in three of the four Corridor areas, except for the Tagus Transboundary Reserve, where the average exceeds 4.7. In terms of the dispersion of ratings, the only remarkable point is the standard deviation for the Tagus Reserve, which is notably lower than the other Corridor areas.

To analyze the value-for-money relationship of tourist services and the overall tourist experience, we must first consider the categories of the variables. In the value-for-money relationship of services, “1” corresponds to a good value, “2” means the relationship is expensive, and “3” indicates a rather cheap relationship. Therefore, if the average ranges between 1.2 and 1.5, it suggests that the value-for-money relationship of the offered services is between good and expensive, and that areas like La Siberia and Monfragüe thus have the optimal rating for this variable. Second, it is important to note that the rating for the overall tourist experience spans from 1 to 5, where “1” is very poor and “5” is excellent. Knowing this, we can highlight that the overall average exceeds 4.2, reaching 4.9 for the Tajo International Reserve. This indicates that the overall tourist experience is generally rated quite positively by respondents.

Below, in Table 6, is a summary of the characteristics of tourist demand in the UEC, as gathered from the surveys.

Table 6.

Summary of the characteristics of tourism demand in the UEC.

Table 6.

Summary of the characteristics of tourism demand in the UEC.

| Dimension | Main Results GENERAL (n = 406) | Villuercas-Ibores-Jara World Geopark (n = 105) | La Siberia Biosphere Reserve (n = 100) | Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve (n = 101) | Tagus-Tejo International Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (n = 100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Main reason to visit: Visiting Natural Spaces and Hiking | 1. Visiting Natural Spaces and Hiking: 47.1% 2. Visiting historical and artistic heritage: 16.3% 3. Sports activities: 11.5% 4 | 1. Visiting Natural Spaces and Hiking: 35% 2. Visiting family and friends: 23% 3. Sports activities and attending local festivals: 16% | 1. Visiting Natural Spaces and Hiking: 61.4% 2. Visiting historical-artistic heritage: 19.8% 3. Birdwatching: 13.9% | 1. Visiting historical and artistic heritage: 36% 2. Visiting natural areas and hiking: 31% 3. Visiting family and friends: 8% | |

| Organization of the trip | Main way to organize the trip: With the family or as a couple | 1.With the family: 30.8% 2. In a group: 31.7% 3. As a couple: 26.9% | 1. With the family: 43% 2. As a couple: 34% 3. In a group: 17% | 1. With the family: 38.6% 2. As a couple: 33.7% 3. In a group: 21.8% | 1. With the family: 37% 2. In a group: 31% 3. As a couple: 29% | |

| Main means of transport: Automobile | Automobile: 76% | Automobile: 75% | Automobile: 68.3% | Automobile: 67.7% | ||

| Accommodation | Main type of accommodation: Rural accommodation, hotel and a relative’s or friend’s home | 1. Tourist flat: 26% 2. Hotel: 21.2% 3. Hostal: 11.5% | 1. Tourist flat: 24% 2. Relative’s or friend’s home: 17% 3. Hotel: 16% | 1. Hotel: 21.8%. 2. Tourist flat: 17.8% 3. Relative’s or friend’s home: 5.9% | 1. Relative’s or friend’s home: 11% 2. Tourist flat: 3%. 3. Hotel: 2% | |

| Main accommodation regime: Accommodation only | Accommodation only: 45.2% | Accommodation only: 59% | Accommodation only: 25.7% | Accommodation only: 7% | ||

| Average overnight stays: 2.22 nights | Average: 2.5 nights Standard deviation: 1.7 | Average: 2.4 nights Standard deviation: 1.9 | Average: 2.3 nights Standard deviation: 1.2 | Average: 1.7 nights Standard deviation: 0.7 | ||

| Information media | Main media for information about the territory: Internet and family/friends | 1. Relatives and friends: 43.3% 2. Through the internet: 41.3% | 1. Relatives and friends: 59% 2. Through the internet: 32% | 1. Through the internet: 56.4% 2. Relatives and friends: 29.7% | 1. Relatives and friends: 39% 2. Through the internet: 38% | |

| Linking | Link to this territory: No links and Relatives/friends | 1. No links: 71.2% 2. Relatives/friends: 24% | 1. No links: 57% 2. Relatives/friends: 39% | 1. No links: 71.3% 2. Relatives/friends: 12.9% | 1. No links: 52% 2. Relatives/friends: 31% | |

| Signposting | Offer valuation | 1.15 | 3.95 | 4.03 | 4.22 | 4.38 |

| Tourist infrastructure | 4.13 | 3.90 | 3.96 | 4.30 | 4.37 | |

| Conservation of historical and artistic heritage | 4.32 | 4.46 | 3.95 | 4.44 | 4.44 | |

| Natural environment and signposting | 4.61 | 4.55 | 4.60 | 4.72 | 4.57 | |

| Local gastronomy | 4.66 | 4.68 | 4.70 | 4.49 | 4.76 | |

| Professionalism of the establishments’ staff | Offer valuation | 4.39 | 4.26 | 4.46 | 4.39 | 4.45 |

| Hospitality and friendliness of the population | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.8 | |

| Quality/price services | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.55 | |

| Tourist experience | 4.55 | 4.26 | 4.43 | 4.61 | 4.90 | |

| Country of residence | Main country of residence: Spain | 1. Spain 2. Germany 3. The Netherlands | 1. Spain 2. Portugal 3. France | 1. Spain 2. Germany 3. Belgium | 1. Spain 2. Portugal 3. France | |

| Autonomous Community of residence | Main autonomous community of residence: Extremadura | 1. Extremadura 2. Madrid 3. Andalusia | 1. Extremadura 2. Madrid 3. Andalusia | 1. Madrid 2. Extremadura 3. Castile and Leon | 1. Extremadura 2. Madrid 3. Andalusia | |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the surveys carried out for the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura [20].

3.2. Tourism Governance Based on Inputs from Stakeholder Focus Groups

The fieldwork on governance in the UEC involved a survey of stakeholders. Twelve people who work in or have information about the tourism governance of the UNESCO Environmental Corridor were interviewed. The sample is part of a larger study on tourism governance in Extremadura, which included a total of 70 key informants. For this reason, in the following table, (Table 7), the responses given by the key informants from the UEC are presented alongside the responses from the general sample of 70 key informants, referring to the other tourist territories of Extremadura.

The profile of the respondents in the case of the UEC is predominantly business owners or members of business associations (42%), as well as municipal employees. Regarding the gender of the respondents in the UEC, six out of every four are women. As for the professional category of the respondents, more than 80% are experts in the field [19].

Table 7.

Summary of UEC governance indicators.

Table 7.

Summary of UEC governance indicators.

| Dimension | Indicator | Response Category | UEC (12) | Extremadura (N = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism strategic plan | 1. Is there a strategic tourism development plan currently in place in your locality/county? | YES | 58.30% | 50% |

| Participation and gender perspective | 2. Were stakeholders consulted in its elaboration? | YES | 66.70% | 44.30% |

| 3. Has this Strategic Plan included an objective or axis that promotes gender equality in tourism entrepreneurship in the locality/shire? | YES | 16.70% | 12.90% | |

| Coordination | 4. Existence of a body for coordination and participation with the tourism sector. | YES | 50% | 40.00% |

| 5. It is chaired by a woman? | YES | 29% | 55.10% | |

| 6. Does this participation body have statutes? | YES | 28.57% | 37.80% | |

| 7. Is there an established accountability procedure? | YES | 28.50% | 30.70% | |

| 8. What coordination exists in the tourism sector in your locality/region? | Average (1–5) | 3.6 | 3.1 | |

| Resource availability | 9. Availability of effective tourism resources | Average (1–5) | 2.7 | 3.1 |

| 10. Average number of employees in the tourism sector | Average | 3 | 3 | |

| Institutional capacities | 11. Effective institutional capacities for tourism development | Average (1–5) | 2.9 | 3 |

| Stakeholder commitment | 12. Commitment of women entrepreneurs | Average (1–5) | 2.3 | 3.17 |

| 13. Commitment of entrepreneurs | Average (1–5) | 2.25 | 3.17 | |

| 14. Modality of participation in the decision-making process | Average (1–5) | 3.18 | 2.7 | |

| 15. Women’s participation in decision-making | Average (1–5) | 3.28 | 2.98 | |

| 16. People with functional diversity | Average (1–5) | 2.5 | 2.18 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura [20].

To establish the level of development of tourism governance in a given territory, the procedure we have adapted is to compare the results of a series of indicators from that territory in contrast to a broader set. The previous table shows a selection of these indicators, with a total of 16.

A series of these indicators (from 1 to 7) corresponds to percentages, while the rest are scored on a scale of 1 to 5. In general, it can be seen that the scores for most of these indicators are in the middle range, in either of the two statistical categories (percentages or averages).

Generally, for both segments, it is found that the indicators with the lowest scores are gender perspective management and functional diversity (indicators 3, 15, and 16). Although the level of involvement and commitment of female entrepreneurs is similar to that of men, few tourism plans incorporate a gender perspective. Furthermore, the consideration of people with functional diversity in these plans is also very low.

The level of “accountability” in tourism governance is very low, and this is a crucial issue in these participatory processes, as accountability ultimately allows for the evaluation of these public policies from a very pragmatic standpoint. This is likely because a significant percentage of territories lack a tourism coordination and participation body, and even when such a body exists, a high percentage of territories lack the regulations or statutes to govern it.

When comparing the governance situation of the UEC to other territories, we highlight the low scores in categories 9, “Availability of effective resources in tourism”, 12. “Commitment of women entrepreneurs”, and 13, “Commitment of male entrepreneurs”.

Regarding “Availability of effective resources in tourism”, it should be noted that this concerns whether: “There is autonomy in managing tourism affairs”, “There are sufficient financial resources for tourism”, and “There are sufficient human resources—officials, employees—”. The greatest deficit in the UEC is in financial resources.

In general, the governance of the UEC territories stands out from the other territories in the following indicators: the existence of strategic tourism development plans; consultations with stakeholders for their development; coordination between the tourism sector of the regions and the development of various participation modalities in the decision-making process; and finally, the participation of women in decision-making.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study presents descriptive data that we consider relevant regarding the characteristics of tourist behavior among visitors to the UNESCO Environmental Corridor of Extremadura, as well as the prevailing model of tourism governance. The findings contribute novel insights derived from research conducted by the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura, within the framework of its agreement with the research team at the University of Extremadura. Specifically, the study examines stakeholder dynamics, participatory mechanisms, and the interplay between governance structures and visitor behaviors. These findings are further enriched by the detailed characterization of tourism demand presented in Section 3.1, which draws on the responses of 406 participants. The data highlight key aspects of tourist behavior, including motivations for travel, types of accommodation, means of transport, and sources of information. Notably, the predominance of nature-based motivations and the relevance of local ties (family and friends) in travel decisions provide useful insights into how destination identity and governance strategies could be aligned to enhance visitor engagement.

For instance, disparities have been identified in the levels of participation and strategic planning across the analyzed territories. While progress has been observed in certain aspects of governance, such as the existence of strategic plans and consultation mechanisms with key stakeholders to promote sustainable tourism, significant limitations persist regarding the inclusion of gender perspectives and functional diversity. Addressing these gaps is essential for ensuring that territories can guarantee inclusivity and the equitable distribution of benefits.

These findings align with previous studies that have pointed to the under-representation of vulnerable groups, overlooking women and people with disabilities in tourism decision-making in protected areas [3,24]. The effective allocation of resources, especially financial and human resources, also remains a key challenge for UEC, requiring further institutional support and capacity-building initiatives.

In particular, the results reveal a great variability in governance practices across the four territories. For example, the Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Global Geopark shows remarkable progress in stakeholder participation and coordination mechanisms, achieving higher satisfaction rates in infrastructure and heritage conservation. In contrast, areas such as the Tagus-Tejo International Biosphere Reserve show shortcomings in average length of stay and participatory diversity, despite excelling in visitor hospitality and overall experience ratings. These disparities reflect broader problems in harmonizing governance practices in regions with different demographic, cultural, and environmental profiles [2,19].

Comparing these findings with other international contexts, research on tourism governance in conservation areas in Latin America has pointed out that lack of resources and institutional fragmentation are common obstacles to participatory management of sustainable tourism [17]. Particularly, in regions such as Chilean Patagonia and the Brazilian Amazon, the difficulty of integrating public and private actors in an effective governance model has generated challenges similar to those observed in the UEC [8]. These cases suggest that strengthening inter-institutional coordination and securing increased funding are key factors for improving tourism management in areas of high ecological value.

Furthermore, it is noted that tourism governance is crucial for the success of tourism destinations, especially in the context of new tourism models [44]. It contributes to improving stakeholder relations and participatory processes in tourism planning and management. In this sense, the tourism typology of a territory influences how governance is implemented.

Reviewing the literature on Smart Tourism Destinations (STD) in Europe, we identify aspects that should be further emphasized in our context moving forward. Specifically, we highlight that digitalization can serve as an effective tool for enhancing tourism governance and fostering more inclusive participation [45]. The implementation of digital platforms in the UEC could facilitate communication between different stakeholders and improve transparency in decision-making [23]. However, as has been observed in similar destinations, the success of these tools depends on the availability of technological infrastructure and the training of local stakeholders. Cases such as the UNESCO Global Geopark in the Azores Islands have shown that digitization combined with participatory governance strategies can improve visitor perception and strengthen territorial identity. Therefore, although governance is one of the five pillars of the Smart Tourism Destination (STD) model in Spain [45], it has not been sufficiently considered in our case, which should be addressed in future research.

In addition, a typology of territorial governance processes in tourism spaces has been proposed, considering their level of depth in the essential characteristics of the model. For example, some case studies in Andalusia carried out with an empirical analysis [46] have sought to demonstrate that the way in which governance models are applied to the tourism industry affects its capacity for development and optimization. In this regard, it is essential to emphasize that the relationship between tourism typology and governance is fundamental to ensuring sustainable development and the effective participation of all stakeholders in tourism activities.

Another relevant aspect is the importance of local identity in tourism governance. Studies in the region of Cantabria, in northern Spain, have pointed out that greater involvement of the local population in tourism planning and management improves sustainability and reinforces the sense of belonging [13]. In terms of implications for tourism planning and management in the UEC, it is crucial that future governance strategies adopt a more inclusive and sustainable approach. The experience of other regions, such as the Biosphere Reserves in Canada and the Global Geoparks in Asia, has shown that the creation of specific policy frameworks for the participation of local communities can strengthen governance and improve the social sustainability of tourism. Also consider the case of the Swiss Alps, where new forms of tourism governance have been implemented by integrating centralized models to improve destination management, challenging traditional models and explaining their evolution from a corporate governance perspective [2]. In this sense, the UEC could benefit from similar strategies, encouraging collaboration between residents and tourism stakeholders through more inclusive participation structures.

Furthermore, the detailed data from Section 3.1 provide valuable empirical grounding for these reflections, as they offer a clear profile of both the types of visitors to the UEC and their behavioral patterns. This includes not only their motivations and preferences, but also their perceptions of local infrastructure, hospitality, and the overall experience—elements that are essential for designing governance strategies that are responsive to real tourist expectations.

The tourism typology and the type of tourism governance—centered on the UEC—explained in this paper have made it possible to establish what type of people visit these natural environments and the characteristics of the participation and decision-making processes that govern the four territories that make up the UEC. However, with the available information, it has not been possible to establish a cause-effect relationship between visitor flows, their behavioral characteristics, and governance models in the tourism sector. Although this relationship is unlikely, it should not be entirely ruled out. It can be assumed that good practices in tourism governance translate into a specific brand identity, a distinct reputational image, and, consequently, the activation of certain segments of the tourism market, leading to differentiated positioning. However, these conjectures could not be established in this study. This is mainly because the information from qualified informants on governance in each of the four territories that make up the UEC needs to be verified and analyzed on a case-by-case basis. In addition, the sampling frame needs to be extended to provide greater consistency—through appropriate triangulation procedures [47]—to the information provided by the 18 key informants on the four territories.

In any case, the cause-and-effect relationship, as an event causing another event, in the context of the tourism sector is complex and multidirectional. Effective governance must consider both visitor flow and their behaviors to achieve sustainable and beneficial tourism development for all. For example, the number of tourists arriving at a destination may vary according to the season, special events, or promotions. At the same time, with regard to visitor behavior, preferences, spending, activities, and attitudes, some tourists may be more adventurous and seek unique experiences, while others prefer comfort and relaxation. All of this can affect how tourism is managed in a destination: regulations, policies, community participation, and collaboration between actors—government, businesses, residents, etc. In this relationship, visitor flow influences the behavioral characteristics of tourists. A high flow of visitors can lead to congestion, impacting the quality of the tourism experience [48,49,50,51,52]. In turn, behavioral characteristics affect governance models. For example, if tourists show an increasing interest in ecotourism, sector leaders may consider implementing policies to protect the environment, etc.

Finally, it should be noted that the study’s reliance on limited stakeholder samples poses a constraint on generalizability. Expanding the sample size and employing triangulation methodologies [47] could bolster the robustness of findings. Additionally, longitudinal studies tracking governance evolution and its impact on visitor flows could provide deeper insights into causal relationships. Future research should delve into the nexus between governance practices and regional branding, exploring how participatory models contribute to reputation and market segmentation. Moreover, integrating digital tools and metrics for real-time governance evaluation could pave the way for adaptive and responsive tourism management strategies [45].

5. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

To some extent, the considerations outlined in the previous section provide insights into the limitations of our study and future lines of research that should be pursued. The qualitative research relies on the opinions of a significant yet limited number of key stakeholders, which restricts the representativeness of the conclusions regarding the assessment of tourism governance. However, the quantitative component includes a sufficiently large sample of surveyed tourists, which strengthens the validity of the findings on tourist demand behavior in these territories. Another important limitation is the absence of a longitudinal analysis, which prevents an evaluation of the evolution of tourism governance and its impact on the sustainable development of the territory over time.

The provided data could be cross-referenced with variables such as origin, gender, and education level, among others, and subjected to statistical decision tests, including correlational analyses and variance analyses between samples, to better understand the explanatory variables that justify tourist demand behaviors. Although the study identifies correlations between governance, tourist perception, and sustainable development, it does not apply association statistics, such as Kruskal—Wallis and Mann—Whitney tests, under pre-established hypothesis frameworks. This additional explanatory analysis would require variable recoding and a level of analysis that falls beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, incorporating this dimension in future research is unavoidable, despite the inherent complexity of establishing direct causal relationships in multidimensional social phenomena such as tourism.

Additionally, we have confirmed the lack of integration of functional diversity and gender perspectives in tourism planning, although this study does not delve into the underlying causes or strategies for improvement. Finally, deficiencies in financial and human resources for effective governance are evident, yet the study does not analyze specific measures to address these shortcomings.

The incorporation of mixed methodologies and comparative studies with other environmental corridors in Europe would allow for a more holistic view of the impact of governance on sustainable tourism development in the UEC. In this way, more effective strategies can be designed to strengthen both territorial cohesion and the competitiveness of the destination at the international level. Furthermore, the implementation of longitudinal studies would facilitate the assessment of the evolution of tourism governance in the UEC and its impact on the social and economic sustainability of the region.

Given the increasing role of technology in tourism management, future research could explore the impact of digitalization on tourism governance, analyzing how digital tools can improve stakeholder participation in decision-making. It would also be relevant to examine the relationship between governance and territorial branding in order to assess how participation and collaborative management can strengthen the tourism identity and the reputation of the UEC.

Finally, a comparative study of other destinations with similar characteristics would help to identify good practices applicable to the UEC and to strengthen tourism governance models in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.-G., M.S.-O.S. and M.C.-A.; methodology, M.S.-O.S.; software, M.S.-O.S.; validation, M.S.-O.S., R.B.-G. and M.C.-A.; formal analysis, R.B.-G.; investigation, R.B.-G. and M.S.-O.S.; resources, R.B.-G.; data curation, M.S.-O.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.-G. and M.S.-O.S.; writing—review and editing, R.B.-G., and M.C.-A.; visualization, M.S.-O.S. and M.C.-A.; supervision, R.B.-G.; project administration, M.S.-O.S. and R.B.-G.; funding acquisition, M.S.-O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded thanks to the Agreement between the Directorate General of Tourism of the Regional Government of Extremadura and the University of Extremadura ‘Research for the generation of tourism knowledge in Extremadura’. Agreement of the Governing Council of the Regional Government of Extremadura in its session of 29 December 2021 and Agreement of the Governing Council of the University of Extremadura in its session of 21 December 2021. Grant number 261/20-A1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the following REASON: The Research Works derived from the agreement for the generation of tourism knowledge in Extremadura are based on anonymous surveys, which do not include personal data. When it is necessary to contact key informants, or for the composition of focus groups, the informed consent of the persons concerned is obtained. In scientific articles derived from this work, such as ‘The UNESCO Environmental Corridor of Extremadura: Tourism and Governance as tools for social sustainability’, the identity of informants and/or respondents is NEVER included, and their identification is not possible, and their consent has ALWAYS been sought. In any case, subject to the data protection criteria of the University of Extremadura (copy_of_PolticadeProteccindeDatosdelaUniversidaddeExtremadura.pdf).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of our research can be consulted in the following link of the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura, of which we are researcher members: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/pie/observatorio.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All the SIC declared in Extremadura became ZECs when their management plans were published in DECREE 110/2015, OF 19 MAY, REGULATING THE NATURA 2000 EUROPEAN ECOLOGICAL NETWORK IN EXTREMADURA. http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1015&Itemid=458 (accessed on 2 February 2024). |

| 2 | Due to space limitations, it has not been possible to add a section explaining the similarities and differences between the tourist behaviour of visitors to the UEC and visitors to Extremadura as a whole. |

References

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M. Formas de análisis de la relación entre anfitriones y turistas. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2017, 8, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P.B.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. Destination governance: Using corporate governance theories as a foundation for effective destination management. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M.; Castro Serrano, J.; Robina Ramiréz, R. “Stakeholders” participation in sustaintable tourism planning for rural region: Extremadura case study (Spain). Land 2021, 10, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries, J.; Jaime, V.; Bucaram, S. Evolución del turismo en Perú 2010-2020, la influencia del COVID-19 y recomendaciones pos COVID-19. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. 2021. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/es/evolucion-del-turismo-en-peru-2010-2020-la-influencia-del-covid-19-y-recomendaciones-pos-covid-19 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- UNWTO. Directrices de la Globales de la OMT para Reactivar el Turismo. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/reiniciar-el-turismo (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Schweinsberg, S.; Fennell, D.; Hassanli, N. Academic dissent in a post COVID-19 world. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, J.C.; Alanís, H.C.; Ferrusca, F.R.; Sánchez, P.J. Análisis del concepto de gobernanza territorial desde el enfoque del desarrollo urbano. Estado Gob. Gestión Pública 2018, 16, 175–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbriggen, C. Gobernanza: Una perspectiva latinoamericana. Perfiles Latinoam. 2011, 19, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Júnior, A.; Augusto-Biz, A.; Almeida-García, F.; Mendes-Filho, L. Entendiendo la gobernanza de los destinos turísticos inteligentes: El caso de Florianópolis-Brasil. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Tour. 2019, 4, 29–39. Available online: http://uajournals.com/ojs/index.php/ijist/article/viewFile/440/319 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Torres, G.; Ramos, H. Gobernanza y territorios. Notas para la implementación de políticas para el desarrollo. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Políticas Soc. 2008, 203, 75–95. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/421/42120304.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Covarrubias Melgar, F. Gobernanza para la ciudad: El poder de decisión de los ciudadanos. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Relacis 2024, 3, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, A.; Pforr, C. The governance of coastal tourism: Unravelling the layers of complexity at Smiths Beach, Westearn Australia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín Gutiérrez, H.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Un enfoque de gestión de la imagen de marca de los destinos turísticos basado en las características del turista. Rev. Análisis Turístico 2010, 9, 5–13. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10902/6383 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- García, F.A.; López, M.C.; Estarellas, P.J.B.; Abella, O.M. Los planes estratégicos de desarrollo turístico (PEDT), un instrumento de cooperación a favor del desarrollo turístico. BAGE Boletín Asoc. Española Geogr. 2005, 39, 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, G.; Anzola-Morales, O. Desarrollo y sostenibilidad: Una discusión vigente en el sector turístico. Let. Verdes Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Socioambientales 2021, 29, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F. Estado y modelo de desarrollo turístico en la costa Norte del Perú: El caso de Máncora, Piura. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia Ramírez, E.; Armesto Céspedes, M. Governance in tourism activity: A systematic review. New Trends Qual. Res. 2023, 19, e879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Turismo; Consejería de Cultura, Turismo y Deportes. Junta de Extremadura. In II Plan Turistico de Extremadura 2021–2023: Estrategia de Turismo Sostenible 2030; Junta de Extremadura: Merida, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M.; Nieto Masot, A.; García García, Y.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. Memoria Turística de Extremadura Año 2021; Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M.; Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Barbosa, R.; Leal Solís, A. El sector turístico del Corredor medioambiental de la UNESCO (CMU) de Extremadura. In Memoria Turística de Extremadura Año 2022; Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2023; pp. 227–256. [Google Scholar]

- RED ESPAÑOLA de RESERVAS de la BIOSFERA (RERB). Available online: http://rerb.oapn.es/red-espanola-de-reservas-de-la-biosfera/que-es-la-rerb (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Grupo de acción local APRODERVI. Available online: https://www.aprodervi.com/mapa.php (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Barrera, J.M. Enfoque de Abajo a Arriba para el Desarrollo Sostenible: La Estructura de Gestión del Geoparque Mundial de la UNESCO Villuercas—Ibores—Jara. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Geoparks, Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, 7–9 September 2017; Oral communication. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Badajoz. Available online: https://economia.dip-badajoz.es/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/Anexo%20de%20inversiones%202022.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Diputación Provincial de Badajoz. Available online: http://muba.badajoz.es/historia.html (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Diputación Provincial de Cáceres. Available online: https://turismocaceres.org/es/turismo-naturaleza/geoparque-mundial-unesco-villuercas-ibores-jara (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Junta de Extremadura. Turismo La Siberia. Available online: https://turismolasiberia.juntaex.es/index (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Villuercas Ibores Jara. Geoparque Mundial de la UNESCO. 2022. Available online: https://www.geoparquevilluercas.es/ (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Parque Nacional del Monfragüe. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/red-parques-nacionales/nuestros-parques/monfrague/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Portal Oficial de Turismo de España. Available online: https://www.spain.info/es/lugares-interes/museo-taurino-badajoz/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Red Española de Reservas de la Biosfera. Available online: http://rerb.oapn.es/red-espanola-de-reservas-de-la-biosfera/reservas-de-la-biosfera-espanolas/mapa/lasiberia/ficha (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Instituto de Estadística de Extremadura [IEEX]. Atlas Socieconómico de Extremadura. Available online: https://ciudadano.gobex.es/web/ieex/publicaciones-tipo?p_p_id=122_INSTANCE_mcWSoN3Sizvs&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_count=1&p_r_p_564233524_resetCur=true&p_r_p_564233524_categoryId=9288796&articleId= (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- García Ferrando, M. Socioestadística: Intorducción a la Estadística en Sociología; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 132–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo Rivas, M.J.; García Ferrando, M. Estadística Aplicada a las Ciencias Sociales; UNED: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 93 and ff. [Google Scholar]

- López-Roldán, P.; Fachelli, S. Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa; Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès): Dipòsit Digital de Documents, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/129382. (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Sánchez Carrión, J.J. Errores de Muestreo: Precisión de los Estimadores en Encuestas Probabilísticas; Dextra Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas [CIS]. Informes del Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Available online: https://www.cis.es/catalogo-estudios/fid/acceso-a-datos (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Grudens-Schuck, N.A. Focus Group Fundamentals. In Methodology Brief; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.; Bejou, D. Tourism destination marketing alliances. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J. Business interest groups in tourism governance. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn, A.; Jobbins, G. Governance capacity and stakeholder interactions in the development and management of coastal tourism: Examples from Morocco and Tunisia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M.; Robina Ramírez, R. Los Grupos Focales (“Focus Groups”) como Herramienta de Investigación Turística; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M.; Nieto Masot, A.; García García, Y.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. Memoria Turística de Extremadura, Año 2022; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J. Governance of recreation and tourism partnerships in parks and protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bruna, D.; Thiel-Ellul, D. Gobernanza en destinos turísticos: El caso de los destinos turísticos inteligentes (DTIs) en España. Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2024, 27, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, P.; Santos, F.J.; Guzmán, J. Applicability of global value chains analysis to tourism: Issues of governance and upgrading. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 31, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Keohane, R.; Verba, S. El Diseños de la Investigación Social. La Inferencia Científica en los Estudios Cualitativos; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Gregory, R.; Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Mondragón-Mejía, J.A. La capacidad de carga psicosocial del turista: Instrumento de medición para el desarrollo sostenible en la turistificación de los cenotes. Cuad. Turismo 2019, 43, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Blanco-Gregory, R.; Mondragón-Mejía, J.A.; Simoes, N.; Moreno-Acevedo, E.; Ortega, I. Crowding standards and willingness to pay at cenotes (sinkholes) of the Yucatan Peninsula: A comparative analysis of local, national and international visitors. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Blanco-Gregory, R.; Mondragón-Mejía, J.A. Percepción de congestión y dimensión social de la capacidad de carga en cenotes de Yucatán. Cuad. Turismo 2020, 45, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gregory, R.; Enseñat-Soberanis, F. La capacidad de carga del visitante desde su dimensión social en destinos turísticos: ¿Herramienta necesaria para un turismo sostenible? In Planificación Regional: Paisaje y Patrimonio; Mora, J., Ed.; Aranzadi-Thomson Reuters: Pamplona, Spain, 2021; pp. 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Blanco-Gregory, R. Crowding Perception at the Archaeological Site of Tulum, Mexico: A Key Indicator for Sustainable Cultural Tourism. Land 2022, 11, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).