Health Crisis and Labour Markets in Globalised Capitalism: The Spanish Social Labour Intervention Model During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Analyse the intervention measures in the field of employment carried out by the Spanish Government.

- To understand the evolution of unemployment in Spain-based on different official statistical sources, in order to obtain the most realistic approximation possible of the destruction of jobs.

- To study the changes in productive organisation introduced by Spanish companies in response to the new social and economic context induced by the pandemic.

- During the state of alarm, the labour intervention carried out by the Spanish Administration focused on the implementation of passive employment policies that mitigated the drama of confinement.

- The destruction of employment and of the productive fabric was not reflected in the labour statistics, either because of the measures adopted by the Administration, including the ERTEs, and/or because it affected groups of workers in the underground economy.

- The pandemic did not actually cause new changes in labour markets but rather accelerated the process of labour transformation that had been occurring due to the increasing implementation of new information technologies and the advancement of the process of economic globalisation.

3. Results

3.1. The Health Crisis as a Social Problem and Labour Intervention by the Administration

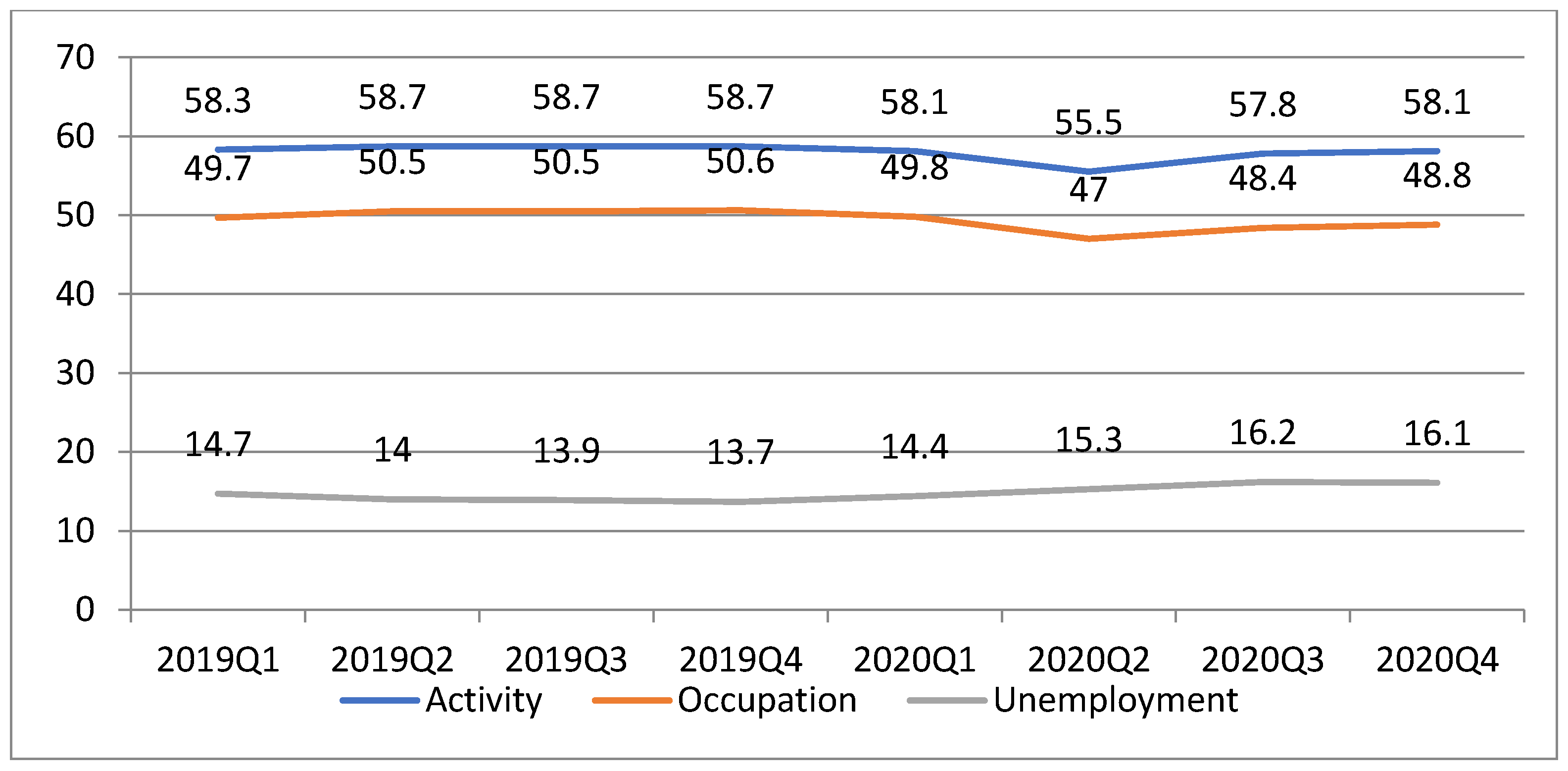

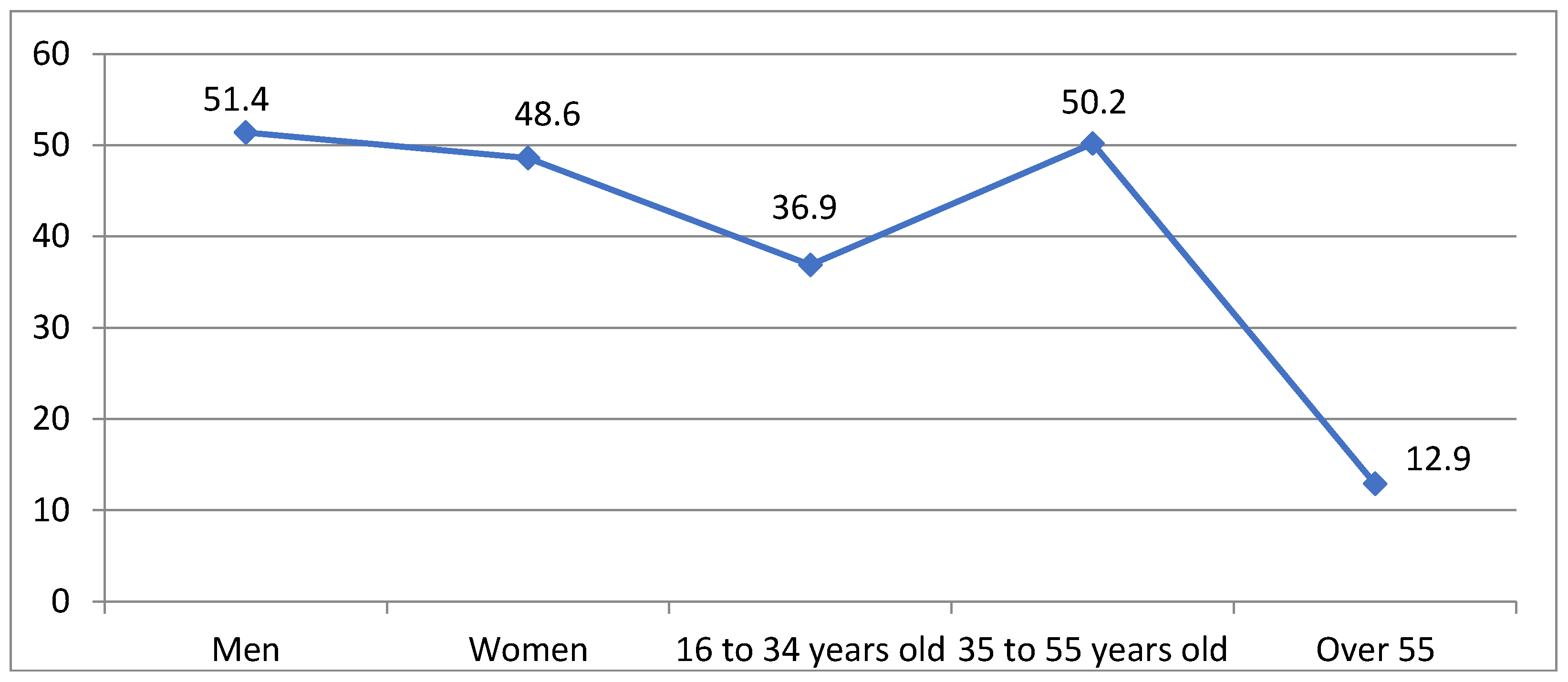

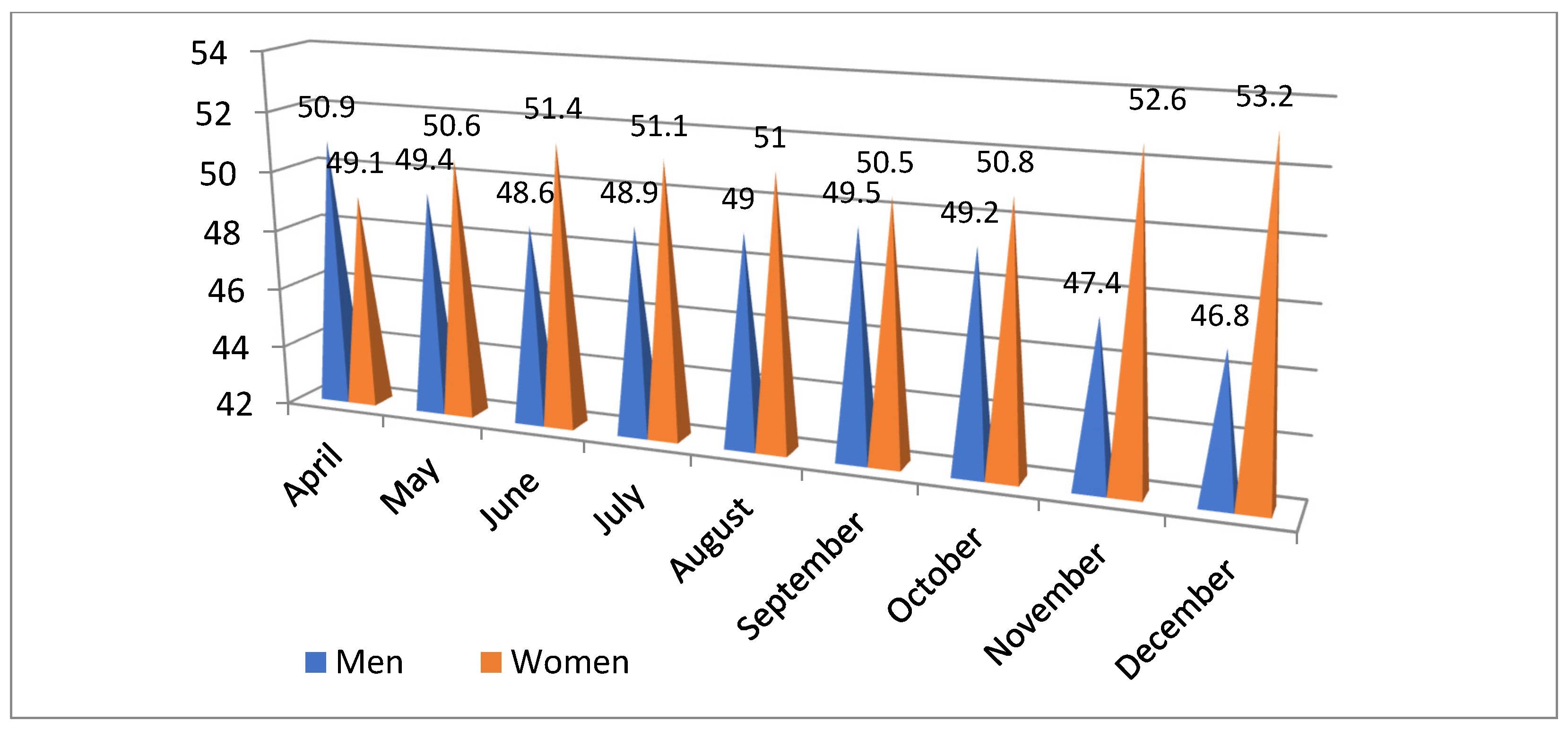

3.2. The Evolution of Activity, Employment and Unemployment in the Healthcare Emergency

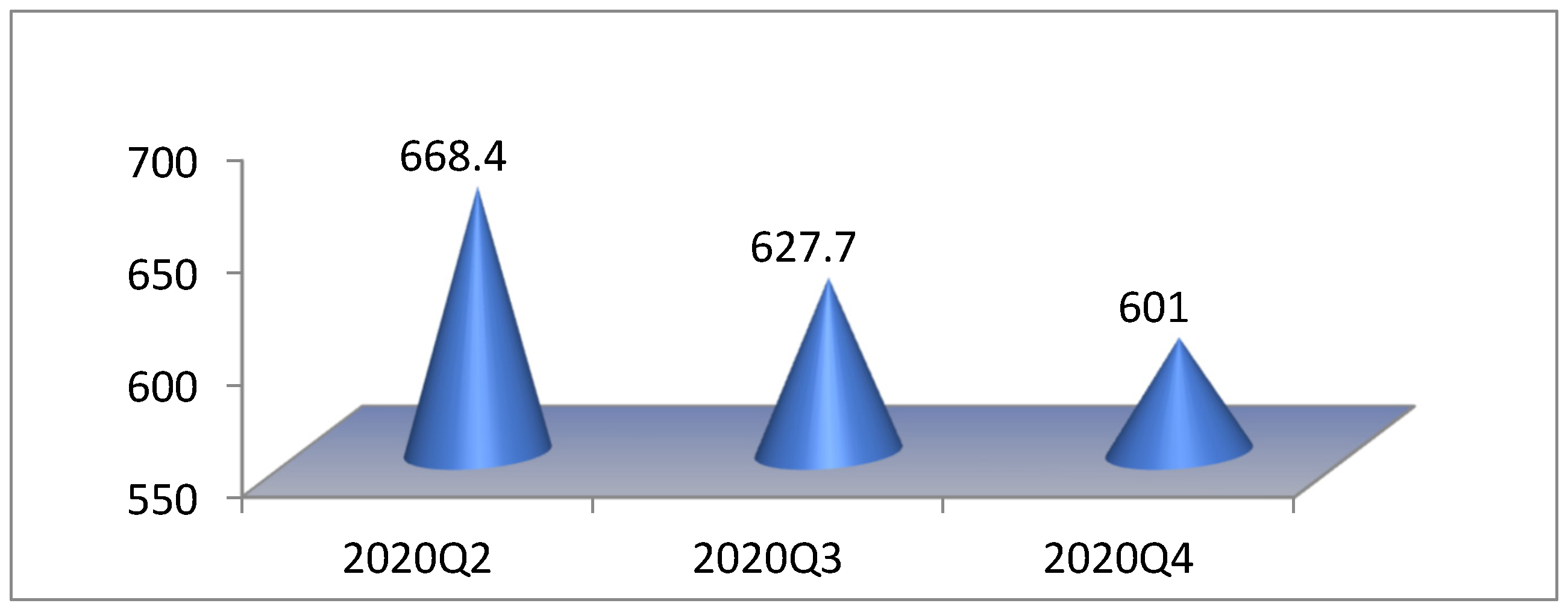

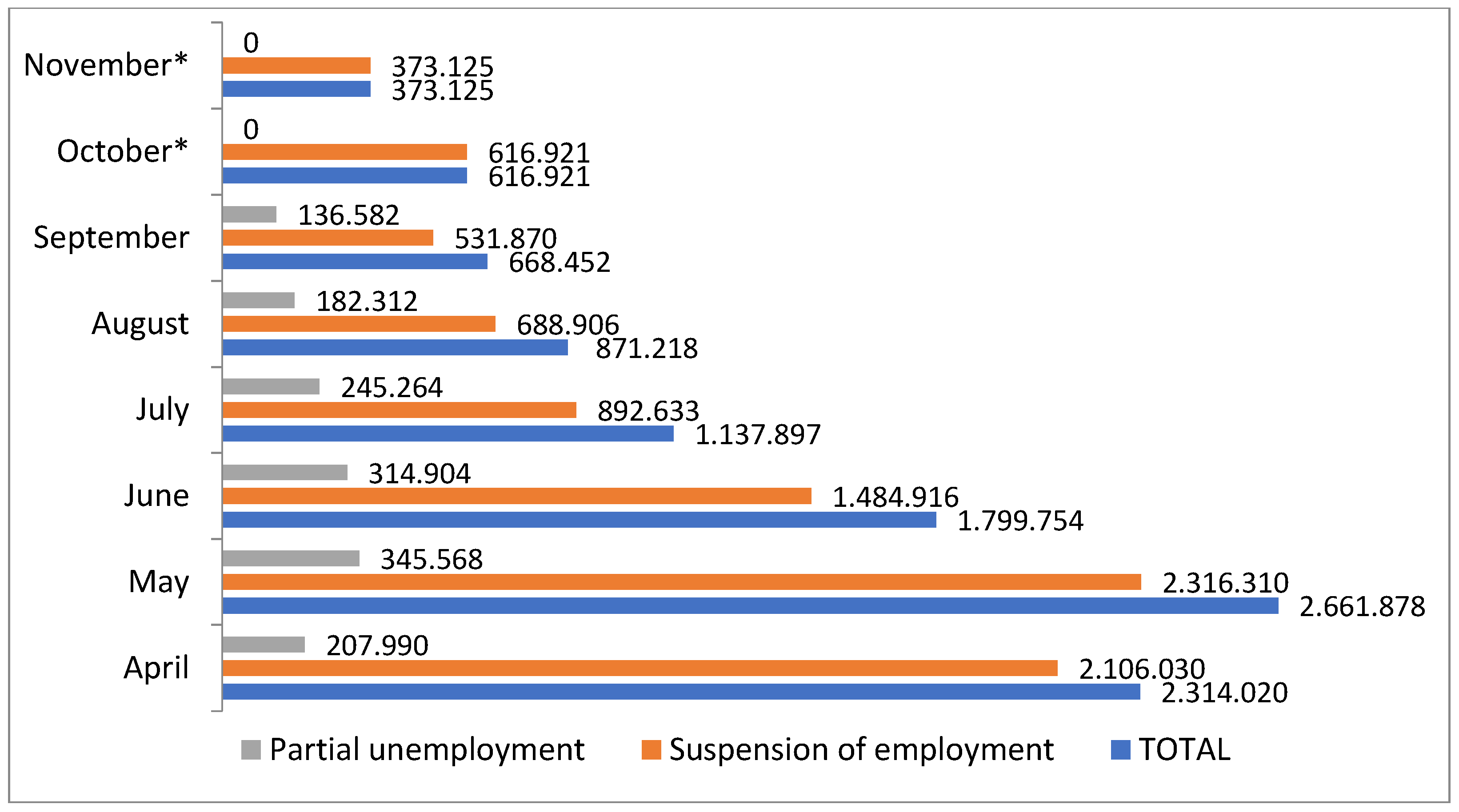

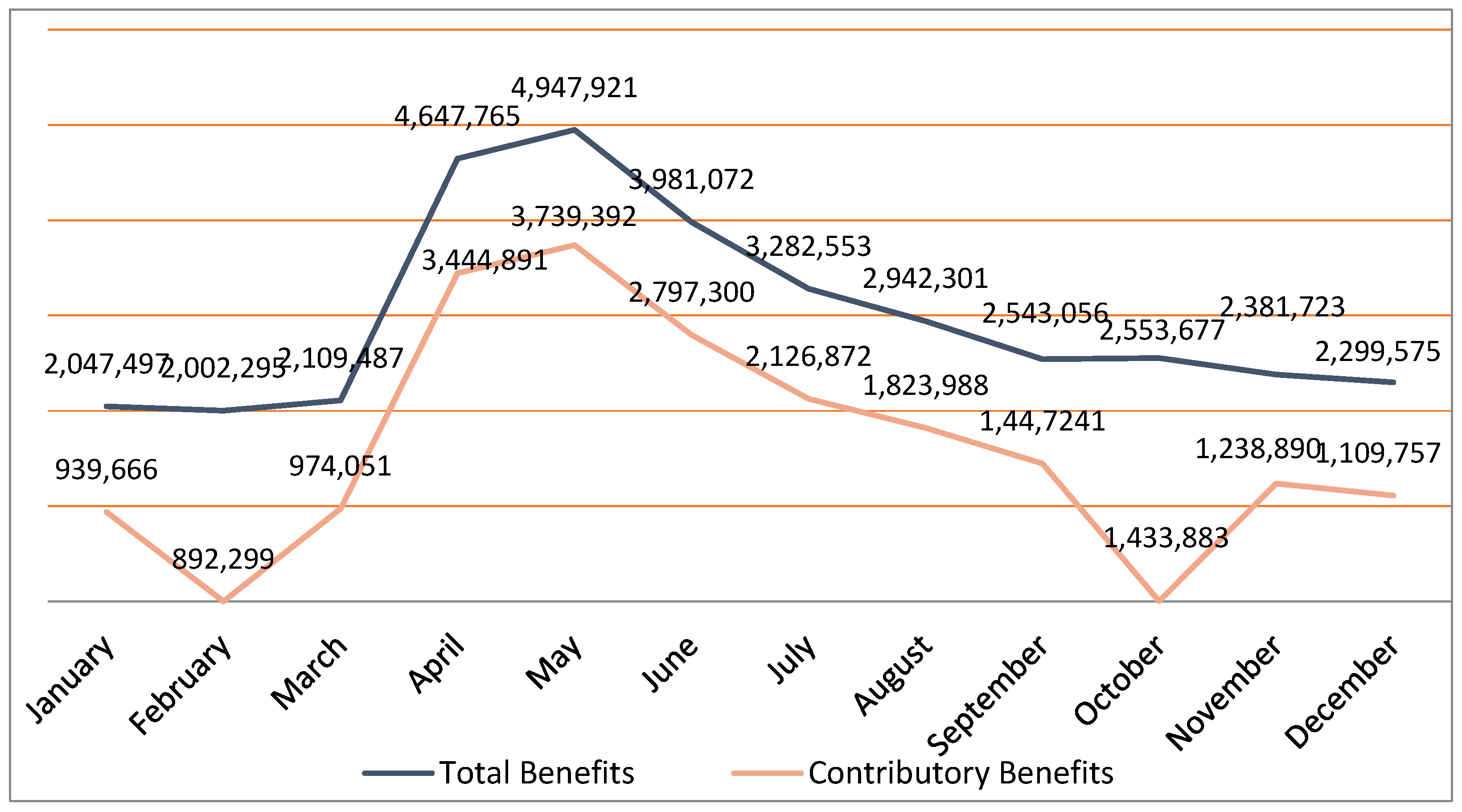

3.3. The Evolution of Temporary Layoffs by COVID-19

4. Discussion

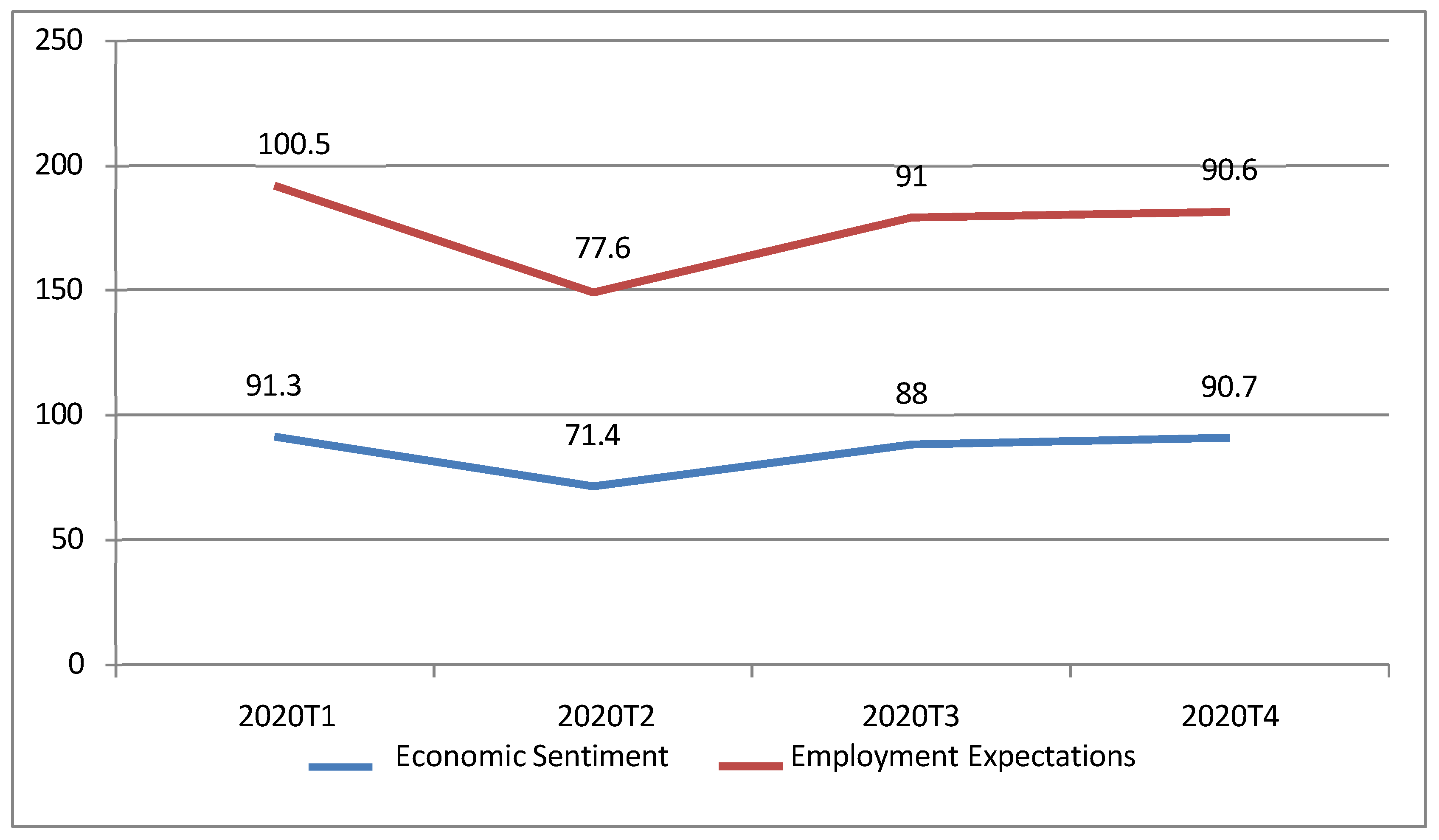

4.1. Economic Confident Indicators

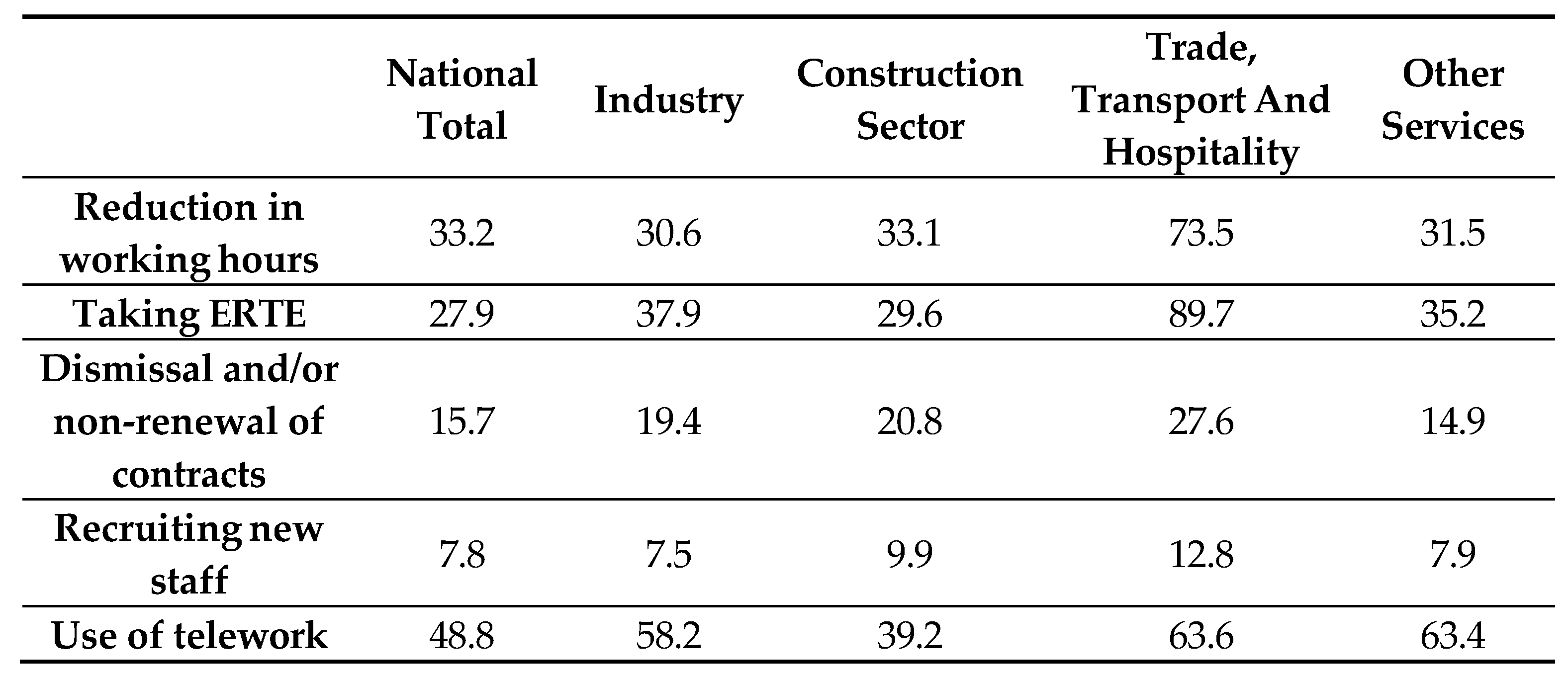

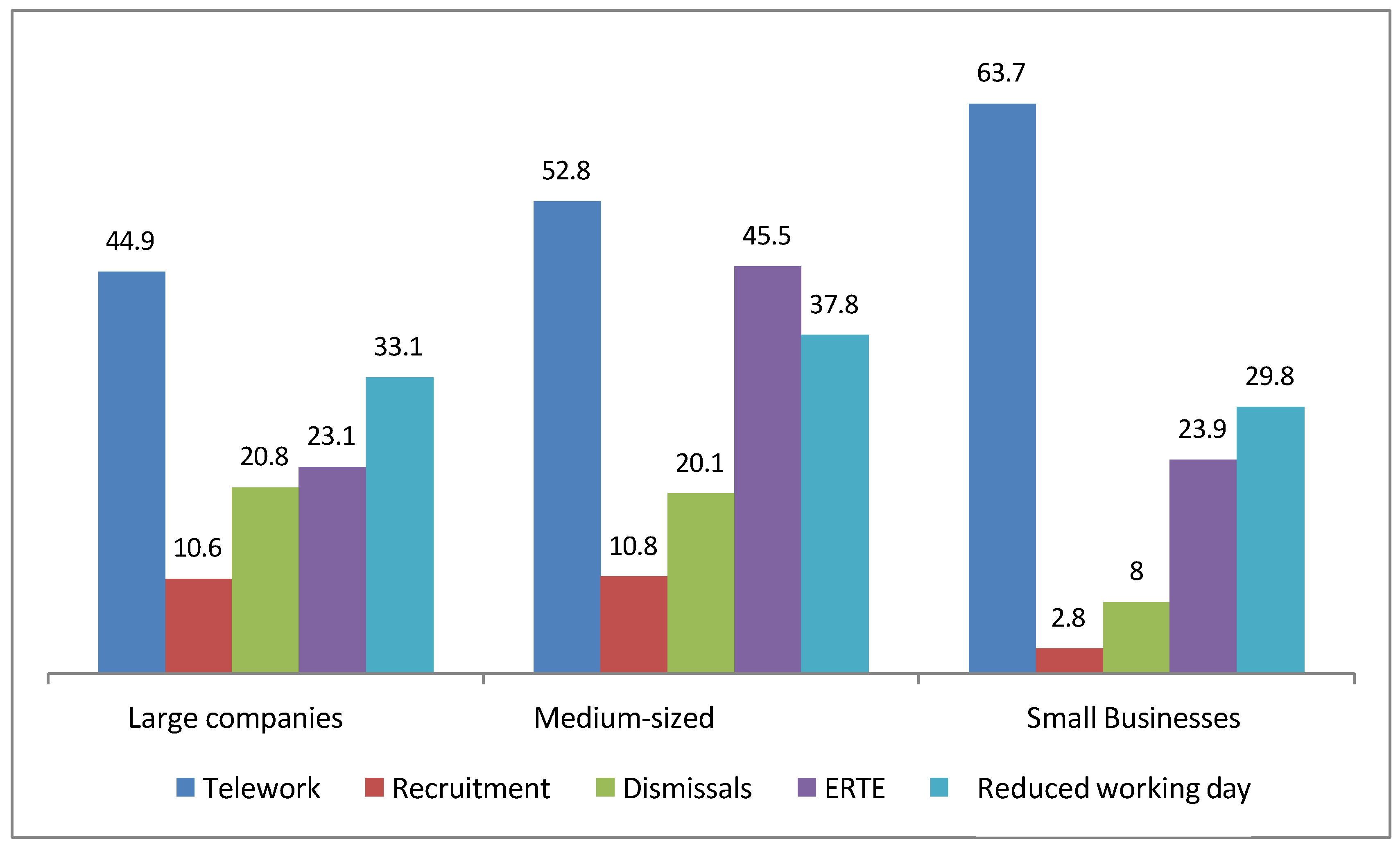

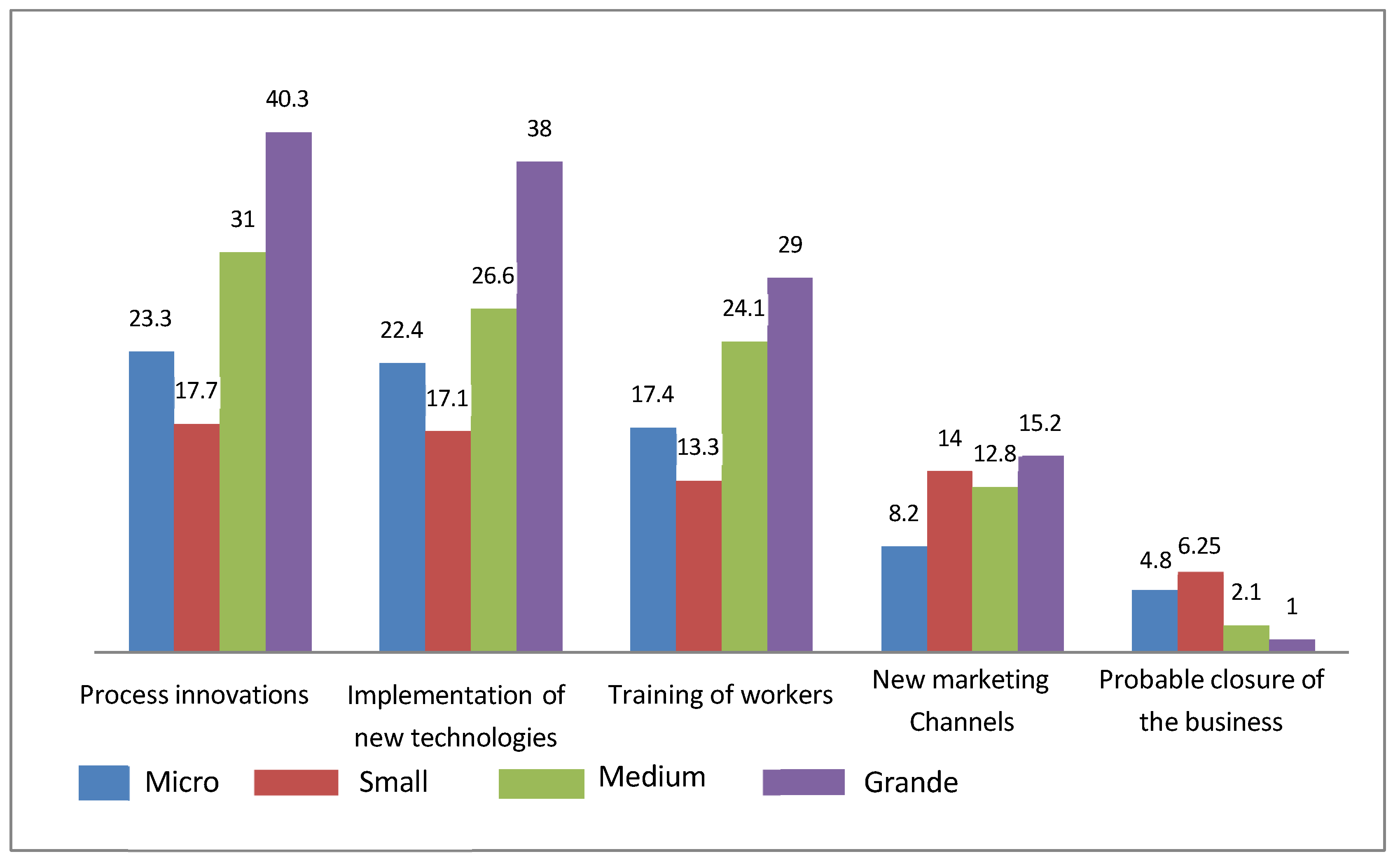

4.2. Changes in Spain’s Work Organisation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In 1978, Deng Xiaoping took the first steps towards the liberation of a communist economy. In the US, Paul Vollcker, at the helm of the Federal Reserve, executed a drastic transformation of monetary policy to combat inflation, regardless of the consequences, adding Ronald Reagan’s policy prescriptions to break the power of workers, deregulating industry, agriculture and resource extraction, and removing the constraints on financial powers, both domestically and globally. In the same decade, Margaret Thatcher, who had already been elected Prime Minister of Great Britain, began to undermine the power of trade unions [6]. It is this trend current globalised economic order [3], p. 17. |

| 2 | Generally, intervention is considered a formal, organised and planned activity, which has to respond to social needs that are perceived and socially legitimised. Contingency plans, on the other hand, respond to new, uncontrolled situations, to which an immediate response must be given due to the serious consequences they have on society [19]. |

| 3 | The health crisis was considered a cause of force majeure by law, allowing employers to apply for an ERTE to reduce workers’ working hours or cease activity altogether. The workers affected by an ERTE ceased to be employees and began to receive contributory unemployment benefits, while the companies that benefited from them reduced all or part of their wage costs and were exempted from paying social security contributions. It was even provided for after the health emergency, once the force majeure causes that motivated the ERTE had been overcome, the workers had to be reinstated in their jobs and could not be dismissed during the following six months, after the end of the “state of alarm”. |

| 4 | These agreements introduced measures to make companies’ production organisations more flexible, as well as economic and fiscal aid for employers. |

| 5 | The concept of the informal economy is complex and must be adapted to the field of study to which it is applied. In the labour field, it refers to tax fraud and labour fraud, understood as the failure to pay taxes on an activity or income and fraud in hiring [25]. |

References

- Zuboff, S.H. La era del capitalismo de vigilancia. In La Lucha por un Futuro Humano; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. El Capital en el Siglo XXI.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie, W. El capitalismo ha muerto. In El Ascenso de la Clase Vectoralista; Holobionte Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. La corrosión del carácter. In Las Consecuencias Personales del Trabajo en el Nuevo Capitalismo; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Expulsiones, Brutalidad y Complejidad en la Economía Global; Katz Editores: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Breve Historia del Neoliberalismo; Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarato, M. La fábrica del hombre endeudado. In Ensayo Sobre la Condición Neoliberal; Amorrortu: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graeber, D. Bullshit Jobs; Akal: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. La gran transformación. In Crítica del Liberalismo Económico; Ediciones la Piqueta: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez López, E. El efecto de la clase media. In Crítica y Crisis de la Paz Social; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, K. La fábrica de la infelicidad. In Nuevas Formas de Trabajo y Movimiento Global; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Trabajo, Consumismo y Nuevos Pobres; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. In the Meantime: Temporarily and Cultural Politics; University Press: Durham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, T.H. Pobres Magnates; Editorial Sexto Piso: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, J. El futuro es un país extraño. In Una Reflexión Sobre la Crisis Social de Comienzos del Siglo XXI; Ediciones de Pasado y Presente: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fumagali, A. La gran crisis de la economía global. In Mercados Financieros, Luchas Sociales y Nuevos Escenarios; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Burkle, F.M.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, M. The European Union’s post-pandemic strategies for public health, economic recovery, and social resilience. Glob. Transit. 2023, 5, 201–209. Available online: www.keaipublishing.com/en/journals/global-transitions/ (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Rhinard, M. Crisis management performance and the European Union: The case of COVID-19. J. Eur. Public Policy 2023, 30, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoba, F. Manual Para la Gestión de la Intervención Social; CCS: Madrid, Spain, 2005; Available online: http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F8/FDO20522/sistemas_publicos.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Felgueroso, F.; García Pérez, J.I.; Jiménez, S. Guía Práctica Para Evaluar Los Efectos Sobre el Empleo de la Crisis Del COVID-19 y el Plan de Choque Económico; FEDEA: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/ap/2020/ap2020-04.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Boscá, J.E.; Doménech, R.; Ferri, J.; Villar a, J.R.; Ulloa, C. The Stabilizing Effects of Economic Policies in Spain in Times of COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Anal. 2021, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente Heras, R. Impacto de la COVID-19 en el Mercado de trabajo. In Un Análisis de los Colectivos Vulnerables; Instituto Universitario de Análisis Económico y Social (IAES): Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/691084 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Martínez, R.; Rodríguez, T.T.; Martínez, A. Unemployment as Social Problems in Southern Countries in the European Union: Analysis of Spain, Greece, Italy and Portugal. In Social Problems in Southern Europe; Entrena, F., Soriano, R.M., Duque, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2020; pp. 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, J.I.; Villar, A. Non-working Workers. In The Unequal Impact of Covid-19 on the Spanish Labour Market; FEDEA: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/eee/eee2020-43.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Gómez Bengoechea, G. Economía sumergida en España. Aproximación teórica y evolución estructural. Estud. Empres. 2014, 146, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola Vacas, M.J.; de Hevia Payá, J.; Mauleón Torres, I.; Sánchez Larrión, R. Estimación del volumen de economía sumergida en España. Cuad. De Inf. Económica 2011, 220, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A.; Martínez, R. La economía sumergida en España. In Documentos de Trabajo; Fundación de Estudios Financieros: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 1–94. Available online: https://es.slideshare.net/slideshow/la-economa-sumergida-en-espaa/26801196 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- FOESSA. Distancia Social y Derecho al Cuidado. In Análisis y Perspectivas; Fundación Foessa y Caritas Bizcaia: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.caritasbi.org/main-files/uploads/sites/29/2021/11/C%C3%81RITAS-analisis-y-persectivas-digital-derecho-al-cuidado.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- OXFAM. Superar la Pandemia y Reducir la Desigualdad; Oxfam Intermon: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 1–54. Available online: https://www.oxfamintermon.org/es/publicacion/superar-pandemia-reducir-desigualdad (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- FTI. Resilience Barometres COVID-19 Report; FTI Consulting: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://www.fticonsulting.com/insights/reports/resilience-barometer-covid-19-report (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Mauleón, I.; Sardá, J. La economía sumergida en España. Estimaciones e implicaciones fundamentales. Ekonomiaz 2011, 39, 124–135. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/273756.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fifi, G. A serious crisis that didn’t go to waste? The EU, the Covid-19 pandemic and the role of ambiguity in crisis-management. J. Eur. Public Policy 2025, 32, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, C.; Magni-Berton, R. A Comparative Journey into COVID-19 Policies in Europe. In Covid19 Containment Policies in Europe; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-52096-9_1 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- INEc. Indicadores de Confianza Empresarial (ICE). In Módulo de Opinión Sobre el Impacto de la COVID-19; Ministerio de Economía y Empresas: Madrid, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/covid/ice/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2020. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2020/living-working-and-covid-19 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Rodríguez, D.; Andrés, J.; Brea, A.; Brunet, A.; de Cadenas, G.; de Rus, G.; del Canto, A.; Duelo, J.M.; Fernández, M.; del Riego, A.G. Por una economía competitiva, verde y digital tras la COVID-19. Econ. Digit. Y Energía. Econpapers 2020, 20, 1–16. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:fda:fdapop:2020-11 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez Martín, R.; Rodríguez Molina, T.T. Health Crisis and Labour Markets in Globalised Capitalism: The Spanish Social Labour Intervention Model During COVID-19. Societies 2025, 15, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060151

Martínez Martín R, Rodríguez Molina TT. Health Crisis and Labour Markets in Globalised Capitalism: The Spanish Social Labour Intervention Model During COVID-19. Societies. 2025; 15(6):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060151

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez Martín, Rafael, and Teresa T. Rodríguez Molina. 2025. "Health Crisis and Labour Markets in Globalised Capitalism: The Spanish Social Labour Intervention Model During COVID-19" Societies 15, no. 6: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060151

APA StyleMartínez Martín, R., & Rodríguez Molina, T. T. (2025). Health Crisis and Labour Markets in Globalised Capitalism: The Spanish Social Labour Intervention Model During COVID-19. Societies, 15(6), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060151