1. Introduction

The large-scale industrialization of the centralized economy has left deep marks on the physiognomy and urban functionality of the Central and Eastern European states. The development of the industrial objectives has exceeded the support space potential of cities, through over-reaching inter-industrial relations, a fact that imprinted on the urban territorial systems a high degree of vulnerability [

1]. Their susceptibility stood out once centralized economic systems collapsed, when the former communist states were confronted with a strong process of deindustrialization, followed, in some cases, by reindustrialization in other areas and on other scales, in accordance with the regional identity of spaces in which urban centres had evolved.

The complex industrialization, deindustrialization and reindustrialization/tertiarization processes carried out during the past seven decades have had a major impact on the relations between urban centres and surrounding, rural and peri-urban areas, an impact that we intend to assess with the help of an important aspect of urban culture: the memory of places.

The purpose of this study is to provide an analysis of how the oversized industrialization of the centralized economy period changed the urban toponymy, thus influencing the memory of places. In this sense, we hypothesize that the dysfunctions registered in terms of urban cultures because of the oversized industrialization policy, and in a broad sense, of the cultural policies pursued by the communist authorities could be entirely rolled back, disappearing once the disturbing factors themselves went extinct.

Despite a rich scientific literature devoted to toponymy during the centralized economy era, this issue has been only fleetingly addressed, either in the form of studies related to urban identity and image [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] to local development and regional planning, to urban culture and toponymy [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], or in general toponymy works [

12,

27,

28]. Therefore, the original side to this study results from the deepening of the industrialization–deindustrialization–urban toponymy–memory of places relationship, applied in a representative space, though less studied from this point of view, of the former Communist Bloc: Romania.

As case studies, we have selected two cities that we deemed representative from this point of view: the country’s capital, Bucharest, a metropolis with strong industrialized macro-regional functions during the centralized economy era, and Galați, which ranks 6th in the national urban hierarchy, the largest steel centre and river and sea port in Romania, a poster-city for oversized development in an industrial field (steel) at odds with the tradition of places and the potential of the urban influence area.

2. Literature

The problem of disturbing the regional identity of urban spaces as a result of large-scale industrialization is a study subject developed mainly after 1990. However, most of the studies target adjacent aspects to the relationships we aim to research in detail, which lends originality to the present work. Moreover, the cities chosen as case studies, although characteristic examples for the researched phenomenon, have been less studied over time, in terms of the industrialization–deindustrialization–regional identity–memory of places relationship.

Important contributions to the theoretical-methodological substantiation of the role of regional identity in shaping the particularities of regional development and planning were made through the studies of [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

29] and [

7], respectively. Dematteis’ study [

2] focuses on the analysis of the relationships between urban identity, the image of the city and their implications for urban marketing, while Raagmaa [

3] and Pike et al. [

4] analyse the role of regional identity in regional development and planning. Anssi [

5] follows the same epistemological lines, which address the mobilization of regional identity, the premise for the transition from delimited spaces to macro-regions defined by relational complexity. Regional identity is also the subject of analysis for the study of conducted by Semian and Chromý [

6] which analyse it in terms of favours/restrictions for regional development processes. Moreover, in the theoretical-methodological sphere is Banini’s study [

29], which focuses on the analysis of the theoretical framework of local territorial identities. The latter study [

7] focused on the impact of an emblematic building in shaping the urban regional identity in Romania’s capital city.

The impact of urban subcultures on the configuration of territorial identity and memory has been deepened by studies such as those of [

8] on London, [

9,

30] on Budapest or [

31] on local branding campaigns. Petsimeris [

8] analyses the ethnic and social division of a global city, having London as a case study; Budapest is analysed in terms of the impact of policies for the commemoration of anti-communist dissent in urban toponymy and places of memory [

9], as well as in terms of the relationship between city marketing and urban culture [

30].

Urban memory reflected in current or extinct toponymy. As a product of urban functionality and territorial identity, it was the subject of research by [

10,

11,

12,

32] or [

33], a study conducted at the level of a German-speaking city (Sibiu) integrated in Romania at the end of the First World War. While the works of Trigg [

32] and Bigon [

12] move along the lines of purely theoretical coordinates, Crețan and Matthews [

10] analyse the population’s responses to the change of urban toponymy in a martyred city (Timișoara), and Light and Young [

11] focus their scientific approach on the policies of continuity/change in urban toponymy.

In Romania, urban toponymy and in particular the issue of street names, as part of urban culture, has developed both through studies performed by historians [

13,

14,

15], linguists [

16,

17,

18], sociologists [

19,

20] as well as geographers [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

34].

The studies carried out by historians, linguists and sociologists used as a documentary basis for our research focus on the issue of street names and street nomenclature, turning to case studies of either a city (Bucharest, [

13,

16,

17,

19,

20]), or the old names of streets, as an expression of the degree of culture in the evolution of a locality [

14,

15,

18].

The contribution of geographers to the study of urban toponymy concerns both the theoretical [

21,

27,

28] and the practical-applicative component. The second category includes the studies conducted by Light [

22,

23] on the renaming of streets in Bucharest after 1989, by Light et al. [

24,

25] on the urban toponymy during the communist period based on the Romanian capital, as well as the studies conducted by Voiculescu [

26] regarding the fatalism reflected in the renaming of the streets in Timișoara post-1989, and Boamfă [

34], regarding the geographical anthroponymy.

Another category of studies that have been used in recording this research is that related to the processes of industrialization, deindustrialization and reindustrialization, respectively, and the impact of these processes on urban physiognomy and functionality, changes in territorial identity and collective memory. In this sense, we have selected the studies of [

35] on deindustrialization and post-industrial cities, and [

36], on the role of creative destruction in urban planning processes, or those applied in Romania by [

37] and [

38], respectively, regarding settlement systems; by [

39] on urban dynamics; by [

40] on Romanian post-socialist cities, or those elaborated by [

41] and [

1] regarding the role of industrialization in urban development.

In this epistemological context, the present study aims to develop the state of current knowledge on the relationships between the trajectory of urban industrial evolution and the causes that influence these trajectories on the one hand (spatial identity as reflected by urban functionality or political-administrative decisions that distort this identity), and on the other hand, the reflection of industrial trajectories in the urban culture and in the memory of urban places, respectively.

3. Methodology and Research Approach

This paper is based on the experience provided by an extensive participatory research process carried out over a period of twelve years (between 2008 and 2020) in the two cities. This is the reason why this moment was selected for the current analysis.

The selection of the two cities was made based on their representativeness for two distinct situations (one is a metropolis with complex functions, the other a large city developed hypertrophically in an industrial branch not based on tradition, supplied by imports stemming from centrally coordinated industrial relations). The two development models are similar to the development trajectories of most former industrialized socialist cities during the centralized economy, but contrast with each other in several ways: demographic size, functional typology and balance between urban functions, as well as the extent of urban/rural relations. Galați was selected alongside the Capital due to its location near the former border between Romania and the Soviet Union, a geographical position which played a decisive role in its industrial development.

We will thus evaluate the frequency with which toponymy related to industrialization (including the toponyms related to the communist political leaders who contributed ideologically to the substantiation of forced industrialization policies or to the data of the political events that marked this process) appear at the same time as the development of industrial landmarks during the centralized economy era and, subsequently, the frequency of their disappearance/change given the transition to the competitive economy. The disappearance of toponymy related to industrialization is symbolic for the deindustrialization process, and the change/advent of new ones indicates the magnitude of the reindustrialization process.

The temporal dynamics of these indices will be a marker for the toponymy changes pertaining to this process, respectively for the long-lasting impact of industrialization on the remodelling of the urban spatial identity.

The respective analyses will also be correlated with the regional identity provided by the natural functionality of the respective spaces, highlighting the manner of their reconversion as a result of the destructuring of the industrial areas created during the centralized economy period.

In order to achieve this research, we will use bibliographic sources and cartographic materials from the respective periods, as well as official statistical data (regarding the dynamic of the urban population and of the employees working in the industry) from the censuses conducted in Romania, correlating them with the information collected by the authors on their field trips.

The paper functions, therefore, at the interference area between economic geography and geographical toponymy, as well as humanities and social sciences, since a series of conceptual clarifications of the notions used is necessary. Thus, we will use three categories of concepts:

Determinant:

- (1.1)

Spatial identity;

- (1.2)

Urban functionality;

- (1.3)

Political-administrative decisions.

Motor:

- (2.1)

Industrialization;

- (2.2)

Deindustrialization;

- (2.3)

Reindustrialization/tertiarization.

Resulting:

- (3.1)

The memory of places.

1. Determinant concepts are those that underlie urban spatial dynamics. They highlight the characteristics of the respective spaces, on the one hand and, on the other hand, the subjective disturbances brought in from the outside, as a result of various political/ideological factors. In this sense, spatial identity (1.1) is thought of as the set of connections between place, space and identity construction [

42], respectively the identity built on the relevant aspects for space/place [

43]. Ref. [

44] defines spatial identity as the identity or perceived image of a place, as opposed to the identity of individuals living there. Thus, each place has particular characteristics that make it unique and help shape a certain behaviour. On the other hand, spatial identity is the premise of the emergence, consolidation and evolution of

urban functionalities (1.2), defined as the professions exercised by the city, its reason for being, the shape it takes when viewed from the outside [

45], respectively the specific human activities that take place in a city, over a certain period of time, influencing the size and character of its urban development and which are conditioned by the city’s location, its climate conditions, natural resources, environmental particularities, as well as the evolution of the city over time [

46]. All these elements make up, in general, the spatial identity. On the other hand,

political-administrative decisions (1.3) trigger a dysfunctional behaviour in terms of the natural evolution of the city by bringing in a political-ideological, external factor of a subjective nature [

47]. This involvement can be beneficial for the city, in accordance with the particularities of the natural environment that provide support for urban activities, thus strengthening its development, or can be detrimental, subordinated to an ideological factor, thus contributing to disrupting the natural relationship between the city and its area of influence. This is also the case of large-scale industrialization during the centralized economy era, which was enacted based on long-distance inter-industrial supply relationships, politically coordinated, which led to major disruptions in both urban and peri-urban areas.

2. Motor (dynamic) concepts, resulting on the one hand from the spatial identity of urban centres, and, on the other hand, from the political-administrative decisions that distorted this identity.

Industrialization (2.1) is defined as the process of a fundamentally developing industry, whose result is that industry becomes the predominant branch of the economy within a territory/city. In situations where this process is politically influenced and is achieved beyond the support capacity of the city, with the disappearance of political and ideological constraints that led to industrialization, the reverse process begins, i.e., deindustrialization, as a natural tendency to rebalance the territorial system, unbalanced due to the initial decisions [

38].

Deindustrialization (2.2) therefore consists of reducing the share of industry in the economy of a country or a human community/city, followed by the reconversion of the jobless labour force [

35]. In large cities, this is done mainly for the service sector or generates divergent migratory flows [

48], often materialized in the decrease in urban population. This process is characteristic of transition periods or economic crises and affects both industrial production and people’s lives, as real wages and living standards decline, while the unemployment rate rises.

Given the transition from a centralized, excessively industrialized economy to a free market globalized system, deindustrialization precedes reindustrialization/tertiarization (2.3) (the development of the tertiary sector to the detriment of the secondary one, in particular). These processes aim at restoring the natural balance of the system of city-area of influence, at other levels and in other fields of activity, in accordance with the potential of the urban centre’s support space.

3. The resulting concepts are the consequence of the first two categories. From this point of view, for the present research we are interested in the

memory of places (3.1), as a part of urban culture, that is, those identity characteristics of places, spontaneous (original) or acquired through political-administrative decisions, reflected in toponymy (respectively in urban toponymy, for the present research). In this sense, the concept of “memory of places” is different from that of “places of memory” attributed to those historical places that awaken collective memory [

49,

50].

4. Background and Preliminary Discussions

4.1. Centralized Industrialization and the Disruption of Spatial Identity. The City, from Large-Scale Industrialization to Deindustrialization and Tertiarization

Rising to power with Soviet support after World War II, the communist parties in Central Europe and the Balkans tried to devise radical strategies for modernizing society. The new political-ideological dynamic shaped the society of these spaces between 1945 and 1989. Its main features can be summarized as follows:

- –

Mimicking the Soviet-Stalinist political model as a paradigm of change, establishing the dictatorship of the communist party, abolishing other parties and the parliamentary system.

- –

The prioritized development of the socializing processes of the economy and rapid industrialization.

- –

The marginalization, even the disregard of the conditions for the expression of the individual aspects of man as a social subject and the atrophy of the critical function of thinking.

- –

The instrumentalization of culture as a means of political-ideological propaganda.

These constants overlapped and interacted in various ways, depending on the circumstances, and shaped the picture of social realities. Their progress was the direct result of political action, the whole society being marked by the domination of the political system. Political life under the hegemony of the Communist Party echoed the characteristics of the Stalinist political system. It was defined by the exercise of the dictatorial power of the communist party, the disappearance of any democratic manifestations within it, the establishment of repression and violence as instruments of supremacy in the party and in society, the abrogation of civil rights and freedoms, the transformation of hypocrisy, denunciation and arbitrariness into governing principles. The Stalinist system transformed the communist party from a political body responsible with the elaboration of strategies for the development and modernization of society, into an administrative institution in charge of executing the decisions made at the very top. It was able to resort to any means necessary, from repression to manipulation, with the sole aim of achieving an economic performance having a positive impact in the social field.

The radical change in the economy was conceived as being linked to a social structure, based on accentuated industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture. Another defining feature of the economy was centralized planning. With its help, the absolute domination of the party/state system over the economy was enacted.

In the long run, the mechanisms for regulating the economy, the single-party economic relations system and state ownership proved to be unsuccessful. The main cause was political, the dominant instrument in the structuring and functioning of economic mechanisms. Instead of the economy regulating itself through specific internal coordinates, it was modelled on voluntary principles, through state intervention.

The bankruptcy of the communist political system in the 1980s highlighted the consequences of centralized planning according to the Soviet model, which was “exported” to the states that came into its sphere of influence after World War II. This model of economic development was based on massive investments in industry, especially in the heavy industry—energy, metallurgy and machine building; on promoting the working class and on army-oriented investments, in an autarchic, political and social framework in relation to the global challenges of the era. Thus, while heavy industry in Western Europe and the United States had already undergone an extensive process of restructuring and refurbishment since the 1960s, and the centre of gravity of economic development shifted towards high-tech industries, and in Central and Eastern Europe the foundations were laid for large industrial investments in metallurgy and machine building. The industrialization of Central and Eastern Europe, out of phase in relation to the western part of the continent, generated profound social and spatial changes, which in turn imprinted differentiated particularities on the cities east of the former Iron Curtain, with consequences that are felt to this very day.

The policy of large-scale industrialization generated a rapid urbanization after the 1945–1950 period, either by building cities near existing industrial centres or on empty lots due to the implementation of new industrial investments, or by expanding existing ones due to migratory flows from rural areas occupied in the new industrial units.

In most cases, centralized development policies have consisted in shifting new industrial investment to small towns with predominantly agricultural or commercial functions, or even to rural settlements, which has led to population explosions based on migratory flows, followed by these settlements being granted city status. On the other hand, the spatial identity of the old urban centres was strongly disturbed by the appearance and development of workers’ replicas of museum cities, cultural, historical or religious centres of tradition, viewed at the time as “bourgeois cities”, aiming to change how they were perceived in the collective mind. Krakow, for example, Poland’s traditional, historical and religious centre, was “mirrored” in 1949 by Nowa Huta, created as its “proletarian counterpart”. Similarly, new suburbs have emerged and developed, some even granted city status: Novi Beograd (1948), Nowe Tychy (1950), Novi Zagreb (1953), Halle-Neustadt (1967) [

51] or Bucureştii Noi [New Bucharest] neighbourhood, integrated into Bucharest in the 1950s, true cities-within-cities, working-class neighbourhoods of various traditional urban centres. Their particular trait remains today that granted by a uniform and monotonous urban landscape [

52], consisting of large collective buildings inspired by Soviet cities, oriented towards creating new social relationships, in which individual personality and any traces of opposition against the political system would be easily annihilated. Wherever this spatial model was implemented, great disturbances were generated at the level of urban spatial identity, resulting in poorly developed territorial structures which were functionally dependent on the central urban nuclei.

Another category is that of cities granted a political-administrative function, which later triggered large industrial objectives. This is the case of Romanian cities such as Târgovişte or Călăraşi, urban centres that saw a strong development in 1970–1980 as a result of their receiving the status of county residences in 1968, followed by the establishment of large steel mills factories, lacking any connection to their functional vocation.

The functional vulnerability of all these urban centres manifested itself brutally after 1990, given the destructuring of the centrally established inter-industrial relations, which created the premises for their “readaptation” to the potential of peri-urban spaces. Thus, functional changes were generated, materialized through deindustrialization and tertiarization, which in most cases led to strong demographic decreases both on the background of a natural balance, as well as—and especially—through migrations.

4.2. Leaders of Centralized Industrialization in Urban Memory

These processes can be quantified by the evolution of the memory of places. A whole series of places in cities (streets, squares, iconic buildings for the city, etc.) that originally, prior to the “great industrialization”, bore names inspired by the local toponymic heritage, in accordance with the spatial identity of those urban centres, were renamed according to the “new proletarian transformations”. They were named after either communist revolutionary personalities, or the dates of key events for the consolidation of the communist political-ideological system, or after newly created industrial landmarks or new purposes for the respective cities, introduced by political-administrative decisions. Even the urban macro-toponymy of Central and Eastern Europe highlighted these aspects, with some large cities temporarily bearing the names of Soviet or domestic political leaders.

Thus, I.-V. Stalin alone, the main artisan of the post-war division of the Continent and of the centralized industrialization of the entire area east of the former Iron Curtain, lent his name to 13 cities in Central and Eastern Europe, up to the former-Soviet Turkestan: Stalingrad, Stalinsk and Stalinogorsk (present-day Volgograd, Novokuznetsk, and Novomoskovsk in the Russian Federation, respectively); Stalin (Varna, in Bulgaria); Oraşul Stalin [The City of Stalin] (Braşov, in România); Qyteti Stalin (Kuçova, in Albania); Sztálinváros (Dunaújváros, in Hungary); Stalinogród (Katowice, in Poland); Stalinstadt (Eisenhüttenstadt, in Eastern Germany); Stalingrad (Nové Město, a suburb of Ostrava, in the Czech Republic); Stalino (Donetsk, in Ukraine), as well as in the Caucasus region—Staliniri (Tskhinvali, in South Ossetia, Georgia) and Central Asia—Stalinabad (Dushanbe, in Tajikistan), respectively Stalinskoye (Belowodskoye, in Kyrgyzstan). After his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, condemned the use of mass repression and the cult of personality during Stalin’s time, most of these cities reprised their original names (between 1956 and 1961) (only Qyteti Stalin in Albania was named thus until 1990, and Albania was the only country from the former Communist Block to remain faithful to stalinism). Similarly, V.-I. Lenin named the largest city in the Baltic Sea basin (Leningrad, now St. Petersburg), as well as the city of Tiszaújváros in Hungary, which went by Leninváros between 1970 and 1991. Other communist leaders had no international interests, naming cities only in their own countries. Karl Marx, a German thinker and philosopher, was one of the authors of the theories that founded socialism and lent his name to the city of Chemnitz (between 1953 and 1990), while Marshall Josip Broz Tito, president of Yugoslavia between 1953 and 1980, named the city of Podgorica, the capital city of Montenegro (between 1946 and 1991). In what once was the former Soviet area, Russian writer Maxim Gorky, the founder of socialist realism in literature and a communist activist, gave his name to the city Nizhny Novgorod (Gorky, between 1932 and 1990); Yakov M. Sverdlov (1885–1919), one of the first Bolshevik political leaders, helped name the city of Yekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk, 1924–1991), and Soviet politician Valerian V. Kuybyshev, an officer in the Red Army, named the city of Samara (Kuybyshev, between 1935 and 1991). Ukrainian Communist leader Grigory Petrovsk named the city Dnieper (Dnipro) (Dnipropetrovsk, between 1926 and 2016) and Bolshevik leader Mikhail Frunze named Bishkek—the capital of Kyrgyzstan (Frunze, between 1926 and 1991). Similarly, in Romania, two industrial cities were named after local communist political leaders: Oneşti (Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, between 1965 and 1990), an important centre of the petrochemical industry, and Ştei (Doctor Petru Groza, between 1956 and 1990), a city which owed its development to uranium mining.

If the artisans of the centralized industrialization policy temporarily named large cities, which were seen, at the time, as symbols of new social relations, the industrial objectives created as a result of these policies often had a local toponymic impact, limited to the cities where they were implemented. Thus, Oţelu Roşu [Red Steel] city in the mountainous Banat area (Romania) was named thus in 1947, after the main product of the steel plant around which the city was founded (the town, originally called Ferdinandsberg, was founded in 1560 by German settlers who built a steel plant, around which the residential area would later be developed), and the city of Victoria (also in Romania), which had evolved as a residential area next to the Ucea chemical plant, was originally named Ucea Fabricii [Ucea Factory], and between 1948 and 1954—Ucea Roşie [Red Ucea].

The memory of intra-urban places is more intensely marked by these aspects, which we will further analyse in due course for two big cities in Romania: Bucharest, the country’s capital, and Galaţi, the largest river-maritime port in Romania and the main steel centre of this country.

5. Results: Case-Studies

The analysis of the case studies will start by highlighting the characteristics of the spatial identity of the two cities, an identity that impresses their urban functionality. In this approach, the maps will play an important role, cartographically illustrating the elements described in the text. The urban function, respectively its spatial expression (functional areas), is the consequence of the spatial identity of the city, but the urban dynamics can also be influenced by a second category of functions, resulting from political-administrative decisions. In the case studies we will present, political-administrative decisions will attract the industrial function (industrialization), thus disrupting the natural, inherent dynamics (in relation to the potential of areas of influence) of cities and influencing the memory of places. The tendency to rebalance the urban dynamics will be achieved through deindustrialization, tertiarization and reindustrialization in other fields.

5.1. Centralized Industrialization and the Memory of Places in Bucharest

Bucharest, the capital of Romania, is one of the largest cities in the south-eastern part of Central Europe (2,155,240 inh.—estimated as of 1 July 2020) and acts as a regional economic and demographic hub. Located at the intersection of old trade routes that connected the Danube, Carpathians and, respectively, the Black Sea with Central Europe, the city owes its natural development to its commercial function, doubled since 1862 by the political-administrative one (when it became the country’s capital).

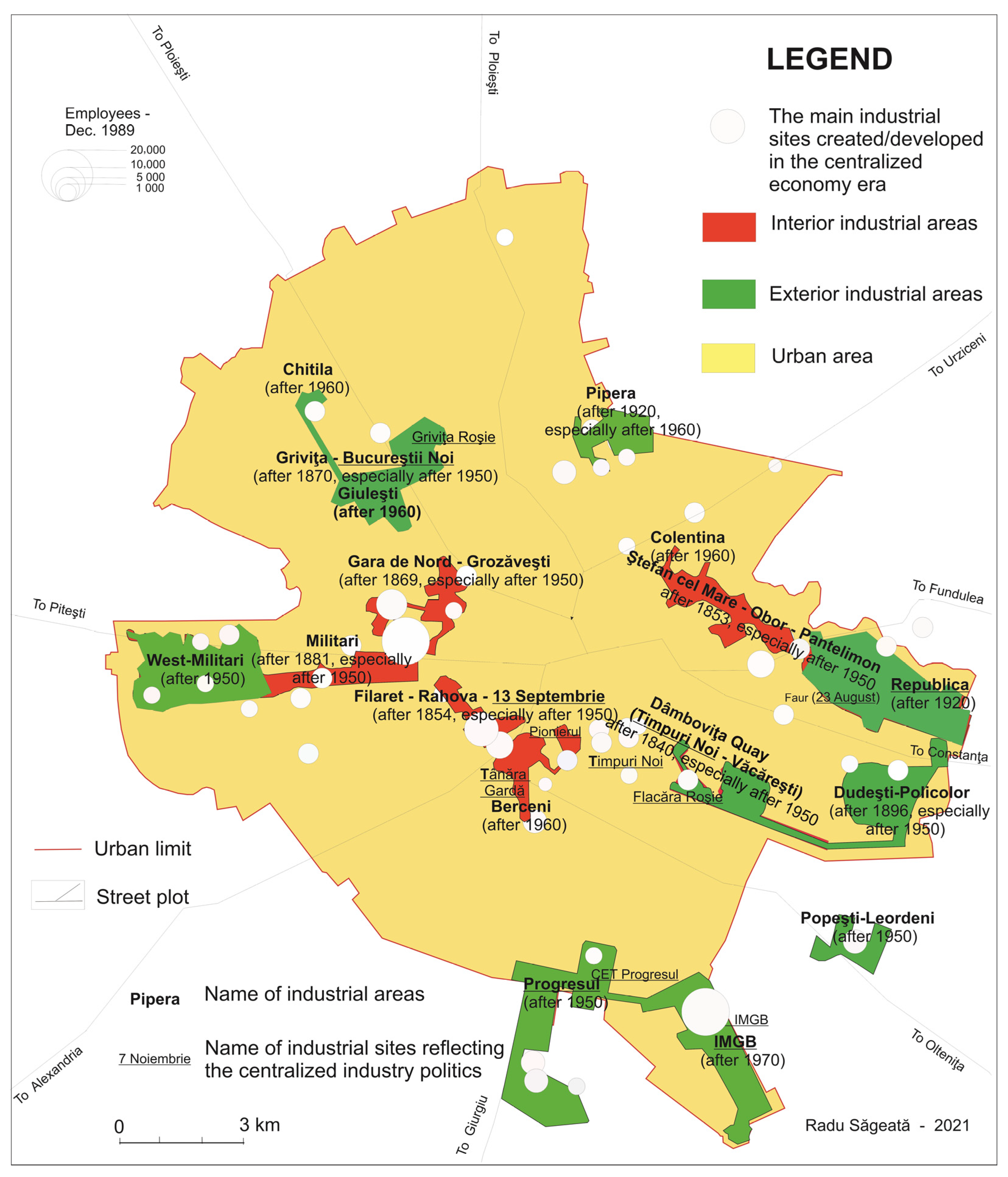

The industrialization of the city began relatively late and was a consequence of its commercial function: the first industrial unit (Assan’s Mill) (Assan’s mill, destroyed in 1995, was the first steam mill in Romania) was built in 1853 by two merchants — George Assan and Ion Martinovici. Starting the second half of the 19th century, the first industrial focal points begin to take shape: on the Dâmboviţa Quay (later renamed TimpuriNoi – Văcăreşti), the Ştefan cel Mare – Obor – Pantelimon areas, the Filaret – Rahova – 13 Septembrie area, joined by the areas Gara de Nord – Grozăveşti, Griviţa, Vest, Dudeşti – Policolor after 1870. In the inter-war period, the industrial areas of Republica and Pipera began to take shape [

53] (

Figure 1). Their hypertrophied development was to take place in the post-war years, aided by the policy of centralized industrialization promoted by the communist authorities, when the industrial landscape of the Romanian Capital was rounded out by the emergence of other industrial areas: Progresul, Berceni, Giuleşti, Colentina, Chitila and IMGB (the Bucharest Heavy Machinery Enterprise/Întreprinderea de Maşini Grele Bucureşti) (

Figure 1).

Thus, over time, based on the evolution of the built space and the radial-concentric morpho-structure of the city, two types of industrial areas were outlined, between which residential areas were built after 1950. Some are interior, corresponding to the old industrial areas, individualized especially in the inter-war period and developed at a later date, and others are exterior, respectively the large industrial areas, built on an empty site, starting the 1950s, during the centralized economy era (

Figure 1).

Thus, if in 1950 the capital of Romania had 110,679 people working in industry, that number reached 210,089 in 1961 and 477,900 in 1982 [

54,

55], exceeding 500,000 at the end of the 1980s, which meant over a third of the population of the Romanian Capital. At the same time, the number of industrial enterprises in Bucharest reached 216 in 1982 and 314 in 1993 [

56], when the privatization process began, which brought with it deindustrialization.

The map illustrates the main industrial areas and sites created and/or developed during the centralized economy period, highlighting the two types of location in relation to residential areas, as well as their development along the main roads in the city.

Due to the high price of land in the central urban areas, the interior industrial areas were most affected by the deindustrialization process, and were replaced, especially between 2000 and 2020, by residential, commercial and business areas.

Industrialization was also visible in the memory of places. The industrial sites created in the inter-war period and later developed were renamed so as to erase from the collective memory their “bourgeois past”, while those created after 1950 were named in accordance with the political tendencies of the time. Most of the names contained the words roşu [red] and nou [new], a direct reference to the symbolic colour of the international communist movement and the new economic and social transformations that the states east of the former Iron Curtain were going through at that time. Industrial enterprises such as Griviţa Roşie, Steagul Roşu, Flamura Roşie, Flacăra Roşie, Tricotajul Roşu, Steaua Roşie or Timpuri Noi contributed to altering the urban toponymic landscape. They are joined by industrial units named after important dates that marked the implementation of communism in Romania and Eastern Europe (23 August, 11 Iunie, 8 Mai or 7 Noiembrie), or after socialist militants (I.-C. Frimu). There were also names such as Socialist Victory, Young Guard or Popular Silk, which in turn lent themselves to the names of streets, intersections, public transport stations or school units (high schools with an industrial profile) [

17,

20,

57,

58] (

Figure 1).

An analysis of the 1962 street names in Bucharest, a suggestive time for the first phase of centralized industrialization, highlights an industrialization index reflected in the street toponymy of only 1.05% (56 toponyms reflecting industrialization out of a total of 5322 streets), which increased to 3.86% in 1988, a year deemed to be the epitome of centralized industrialization in Romania (263 toponyms reflecting industrialization out of a total of 6820 streets). From a qualitative point of view, important changes also took place: if at the beginning of the centralized industrialization process, this endeavour was predominantly exemplified through the names of small streets and pedestrian alleys, names related to industrialization were later assigned to important streets for the large residential area developed as a consequence of centralized industrialization [

59]. One such example is Metalurgiei [Metallurgy] Boulevard, which provides access to the southern industrial area of the Romanian Capital, with a predominantly metallurgical and machine building profile, or the Industriilor [Industries] subway station, the end point of the subway line that ensure access to the western industrial area (Militari).

Additionally, as the communist political regime was consolidated, street names appeared in the urban macro-toponymy of the Romanian Capital meant to illustrate this particular aspect. One such example is the Victory of Socialism Boulevard (currently renamed Bulevardul Libertăţii [Liberty Boulevard]), designed to be a polarization axis for the New Civic Centre, built on the North Korean architectural model [

60] on the site of the former Uranus neighbourhood that had been demolished following a political decision [

61].

After 1990, but especially after 1992–1993, as a result of the collapse of the system of centrally established inter-industrial relations and the failed privatizations, a wide process of industry decline began (deindustrialization), with profound social implications (unemployment, migration, decline in living standards, a surge in crime rates and marginal social phenomena). Against this background, new changes took place in terms of urban toponymy, with cities returning to their spatial identity. A good example in the case of Bucharest is a decrease in the industrialization index reflected in urban toponymy, which fell below the 2% threshold (1.97% in 2016).

Against the backdrop of the more developed infrastructure, deindustrialization affected the Capital to a much lesser extent in relation to the rest of the national territory, which was highlighted by a considerable increase in the share of the Capital industry in the total Romanian industry from 13.6% in 1982 [

55] to 43% in 2004 [

62]. However, it has substantially contributed to an extensive remodelling of the urban space by reconverting the former industrial areas into commercial/service and residential areas [

41,

61,

63].

5.2. Centralized Industrialization and the Memory of Places in Galaţi

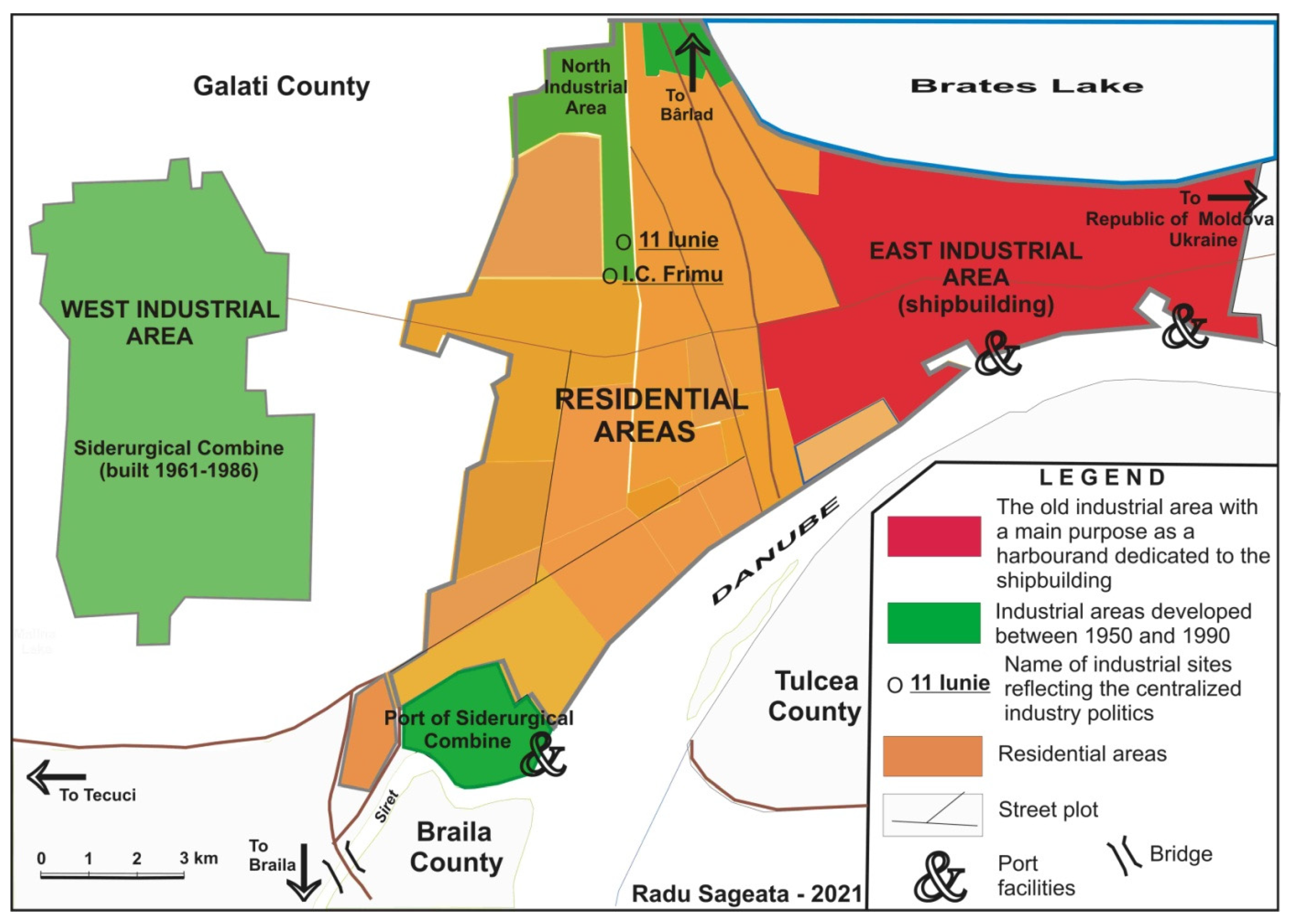

Also called the “red city” due to its strong industrial development during the communist period, Galaţi (304,873 inh.—estimated as of July 1, 2019) is the sixth largest city in Romania (after Bucharest (2,133,941 inh.), Iaşi (381,118 inh.), Timişoara (328,480 inh.), Cluj-Napoca (325,179 inh.) and Constanţa (313,156 inh.) (Source: The National Institute of Statistics—1 July 2019, estimate). Located on the eastern border of the European Union, near the political border between Romania and the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, the city evolved in an area of a triple hydrographic convergence—the Danube with the Siret and the Prut rivers (

Figure 2)—owing its identity to its port-commercial function, which also drew in shipbuilding activities [

64]. Prior to the unification of the Romanian Principalities (1859) it functioned as a port of Moldavia (in competition with the city of Brăila, the main port of Wallachia), being currently the largest river-sea port on the Danube. Shipbuilding, an old tradition in the city, acquired an industrial dimension after 1895, when the shipyard was reorganized under the name of The Mechanical Engineering Plant and Iron and Concrete Foundry, which also engendered the establishment of complementary industrial units, both in the interwar period (nail and chain factory—1922, tin rolling mill—1923), as well as after 1950 (Wire, nail and chain plant—1955, Mechanical Plant—1961) [

65].

However, the political decision that radically changed the territorial identity of the city, and with it the dynamics of its demographic and urban-civic development, was the establishment, here, in the early 1960s, of a large steel plant with integrated production flow, following the model of large steel centres of the former USSR. It is a typical model of port steelmaking, as, given the economic relations between the former socialist countries, its location on the Maritime Danube was designed to be supplied with iron ore from Krivoy Rog [Kryvyi Rih] and coking coal from the Donbass Basin (Ukraine) (

Figure 2).

The construction, and later expansion of the steel plant, influenced, on the one hand, important migratory flows of the labour force employed in the steel industry, and on the other hand the explosive development of other downstream industrial units, which use sheet metal and steel subassemblies, as well as complementary industrial units, for the female labour force, especially in the textile and food industries. The strong industrial development triggered a three-fold increase in the city’s population in just three decades, from 107,248 inhabitants in 1961, when the construction of the steel plant began, to 326,139 inhabitants in 1990, when the deindustrialization process started. This demographic evolution has, in turn, led to a rapid development of the built area particularly in the western part of the city, adjacent to the steel industrial area, by building new neighbourhoods, generally high-rise edifices, in a hurry and as cheaply as possible, which do not correspond, for the most part, to current standards of comfort and safety [

66]. On the other hand, this development has generated a strong polarization of services (especially in terms of specialized services) in the central area of the city while decreasing them in the large working-class neighbourhoods of the west, home to the highest population densities. These territorial discrepancies subsequently favoured the post-industrial tertiarization process.

The map illustrates the arrangement of industrial areas on the outskirts of the residential area which, when associated with the barriers imposed by hydrography (the Danube, Lake Brateș and Siret River), considerably limits the expansion of residential areas. This phenomenon is typical of the city of Galați and prompts the reconversion of the functional areas within the same built perimeter.

The social-urban dysfunctions were joined by dysfunctions in terms of the city image [

67] and the collective spatial memory. From a city with a commercial-port mission, which later became an industrial-port calling, imprinted by its territorial identity, its urban branding [

68] became dominated by the steel industry. The steel plant in Galaţi became, in the second half of the 1980s, the largest industrial unit in Romania (of about 40,000 employees), and Galaţi became the only large city in Romania whose economy was dominated by a single large industrial unit. This fact is also highlighted by the memory of urban places. The main traffic arteries in the new residential areas, built as a by-product of the steel plant’s development, have names related to the steel industry: Siderurgiştilor [Metallurgy] and Oţelarilor [Steel workers] boulevards; Laminoriştilor [Rolling millers] street etc. For Galaţi, the analysis of the industrialization index reflected in the street toponymy shows an increase from 5.12% in 1962 (at the time, the main names related to industrialization were significant for the port-industrial function of the city: Navelor, Elicei, Portului, Strungarilor streets, located near the eastern industrial area), when the construction of the steel plant started, to 6.62% in 1988, the city’s moment of maximum industrialization, followed by a slight decrease to 5.87% in 2016, mainly due to the replacement of the names related to the dates or to the representatives of the socialist movement (6 Martie, 11 Iunie, I.-C. Frimu etc.) (

Figure 2) (thus, the name of the 6 Martie Boulevard was replaced after 1990 with Basarabia Boulevard, while the 11 Iunie Square and Park were replaced with Rizer Square and Park, and the I.-C. Frimu neighbourhood was renamed Aurel Vlaicu, thus creating a reintegration of the urban memory into the spatial identity of the city).

The relatively small decrease in the industrialization index reflected in the post-1989 street toponymy can be explained through the extent of the development of the steel industry in Galaţi during the centralized economy era. Despite the deindustrialization of the steel industry, it continues to remain the dominant industrial branch in the city’s economy, which justifies the prolonged existence in the urban toponymy of names related to the steel industry. In addition, these names were not given by replacing pre-existing names, more relevant to the territorial identity of the city, as happened in other urban centres (including the Capital), but were assigned to new roads, which cross new urban micro-neighbourhoods (in Galaţi, most urban micro-neighbourhoods built in the years of the centralized economy era do not have proper names but have been called “Micro” (from micro-urban neighbourhood), followed by a number (e.g., Micro 17, 19, 20, 21; Micro 38, 39, 40) built on empty lots, as a result of population growth due to the establishment of the steel plant, thus contributing to the territorial identity of the city.

6. Conclusions

The two analyses highlight the correlation between the urban spatial identity and the memory of places reflected in the urban toponymy, given some dysfunctions due to some political decisions pertaining to large-scale industrialization. These are characteristic of the Central and Eastern European space, which was under Soviet political and ideological influence between 1945 and 1989.

The location of large industrial objectives in cities lacking a true industrial tradition has disrupted the relations between cities and their areas of influence leading to artificial developments of the built fund. Subsequently, the disappearance of political-ideological constraints that generated these hypertrophic developments led to a rebalancing of territorial systems through deindustrialization and tertiarization. The disappearance/reconversion of the industrial objectives also had a strong impact on the urban toponymy by replacing the names that reminded people of the communist period in favour of others related to the national specificity and the tradition of the places in question. This demonstrates the hypothesis stated at the beginning of the paper that the dysfunctions registered in urban cultures as a result of the policies pursued by the communist authorities during the centralized economy era are reversible in nature, receding with the disappearance of disturbing factors and having an impact on the memory of places, which tends to fade over time. These are practically a stage in the evolution of the cities of the countries that made up the former Communist Bloc [

25,

60].

The first example is typical of a European capital of metropolitan size, with multiple functions and the role of polarizing the national and even transnational territory. In this case, the functional changes stemming from political decisions have disturbed, in time, the memory of places through names that illustrate the industrialization process, respectively the historical data/events and protagonists of the centralized economic development policy. The political and economic changes that started in 1989 considerably blurred this process, as illustrated by the decrease in the value of the industrialization index reflected in the street toponymy, confirming a tendency of realigning urban memories to the characteristics of the city’s territorial identity.

The second example is indicative of a city in which an industrial giant was inserted as a result of political decisions, without any connection with the territorial identity of the respective urban centre. This model of industrial development was not unique—the Galaţi steel plant is part of a real generation of such industrial units, as are the steel plants in Nowa Huta (Poland), Košice (Slovakia), Eisenhüttenstadt (East Germany), Kremikovtsi (Bulgaria), as well as the major steel plants in the Russian Federation and Ukraine, most of them being developed, however, based on local raw materials. The industrial development brought with it a strong demographic growth and a development of the built area, as new residential areas were built on an empty site in the vicinity of the steel plant or by demolishing the old housing stock; a new urban identity was created alongside a new urban brand that joined the natural identity conferred by the proximity of the city and which, due to its size, would later diminish, but which continues to exist despite deindustrialization and tertiarization.

The two selected case studies complement each other and are meant to provide a more evocative picture of the impact the communist period has had on the urban culture of the localities east of the former Iron Curtain and, in particular, on the urban culture of Romanian cities.