Abstract

This article examines the contemporary industrial semiotic landscape in the town of Velenje, Slovenia, to determine the (positive or negative) collective imaginaries and discourses about industry in the local community. To this end, the semiotic landscape is mapped for signs and symbols of past and present industry, 33 randomly selected short interviews are conducted to understand the residents’ attitudes towards industrial symbols and industrial development in general, and a content analysis of official strategic documents is conducted to determine how industry is represented by officials and whether there are efforts to reimage the town. We found that the industrial past and present are well represented by industrial symbols and are a matter of pride and collective identity for the residents. However, the industrial tradition is hardly represented in official documents: Influenced by the prevailing post-industrial discourses, local authorities have begun to construct new territorial identities in order to increase the town’s attractiveness and economic growth. Currently, both ideas seem to coexist in Velenje. We argue that industrial symbols can become a reference point to create an alternative perception of a modern consumer society based on past industrial values, such as collective well-being, solidarity, and equality.

1. Introduction

In recent years, many (post)industrial cities have been using reimaging as a response to the acute problems of industrial decline, economic restructuring, and the increasing urgency of securing service sector activities [1]. To this end, (post)industrial cities are constantly seeking new niches to distinguish themselves from the gloomy image of their industrial ancestors. In doing so, they do not have to rely on one single narrative but can develop a range of compatible multiple narratives simultaneously [2]. For example, Turin has started to invest heavily in creative and cultural branding strategies to change its former image of an industrial one-company city into a smart city (targeting the internal market) and a gastronomic paradise (targeting the external market) [3].

Cities, towns, or regions often resort to various strategies to reinvent themselves as centers of creativity and experiences [4], knowledge [5], or culture [6], usually to attract individuals, tourists, investors, and firms. However, city reimaging strategies can often provoke conflicts between traditional values and norms on the one hand and modern development aspirations on the other; see for example Willer’s account on rebranding conflicts in industrial cities in America’s Rust Belt [7]. Reimaging strategies raise fundamental questions, such as how a city is represented, how the images are developed, what kind of investments are made in the city in response, and how the benefits are distributed among city residents. There is a particular need to address these kinds of issues in the context of old industrial cities that have undergone severe economic and social changes. There are accounts of some (post)industrial cities implementing ambitious reimaging strategies to appeal to a variety of external audiences [8]. The problem with these branding strategies is that they may create a skewed image of the place and treat it as a marketing product instead of promoting the distinctiveness of the place or other intrinsic place-based qualities [9].

Local perspectives of an industrial town may vary substantially from the official version of the identity presented by marketing professionals. Said perspectives emanate from personal experiences, memories, place-based collective imaginaries, and emotions related to specific places [10]. Reimaging strategies should be based on place-specific values and embedded social practices and should strive to convey positive cultural legacies and historical discourses [11,12]. The case study of six small industrial municipalities in Sweden shows that place branding in a broader sense should not only be seen as a matter of selling the municipality to “outsiders” such as tourists and potential investors but should also be regarded as a tool to generate a discourse of attractiveness and pride for the local population, i.e., “insiders” [13]. This is particularly important for industrial places, which are not typically recognized as being attractive according to today’s standard imaginaries and visual appeals.

The article first contributes to the understanding of how industrial legacy and industrial discourse are interpreted by the residents and how they influence identity formation in a post-industrial world. We argue that industrialism is perceived positively in the residents’ experiences, memories, and emotions. This is expressed through visual and non-visual symbols in the urban landscape, i.e., the semiotic landscape. Secondly, we argue that modern post-industrial policy discourses and branding strategies lead policymakers and officials to develop strategies with a less positive and uncomplimentary view of industrialism. They try to impose new signs and symbols in line with post-industrial development paradigms. The aim of this paper is to examine how past and present industrial activities are interpreted by the local people and the policy makers and whether there is a conflict between the two. We examine the contemporary industrial semiotic landscape to determine whether it reflects positive or negative collective imaginaries and discourses. To reach this aim, we set two specific objectives:

- (a)

- To scan (map) the urban landscape of the industrial town of Velenje in Slovenia and reveal its industrial imaginaries through the signs and symbols of industry;

- (b)

- To scan policy discourses in Velenje to determine how industry is portrayed by the officials and whether there are efforts to reimage the town.

To achieve the first objective, we analyze the industrial semiotic landscape for visual symbols and conduct short interviews to complement the mapping exercise and gain an understanding of non-visual industrial symbols (Section 5). To achieve the second objective, we analyze official strategic documents to determine how industry is represented by policy makers (Section 6). In Section 7, we discuss our findings, relate them to theory, reflect on the aim of the study, and conclude the article with key theoretical and practical implications.

2. Theoretical Overview

2.1. Industrial Semiotics and Industrial Identity

The construction and deconstruction of material space within cities is directly involved in a process of signification, which gives meaning to specific symbols [14]. Observation and interpretation of those symbols can tell us more about their meaning, forces, and influences beyond their physical form [14]. Signs in space can tell a story about sociocultural, historical, political, and other contexts of a certain space and the people that live in it [15]. They always contain a temporal dimension and can be a repository of the past, the present, and the future: “Signs lead us to practices, and practices lead us to people…” [15] (p. 59). They are particularly important in the spatial context, as they constitute an important part of territorial identity [16]. Symbols give meaning to a territory, contribute to its institutionalization, and regional or local formation [16]. According to the typology of symbols in towns and cities [14], industry can act as a symbol in many varieties. Material symbolism, for example, is visible in factories, monuments to workers and miners, architecture, dwellings of workers, etc. Emotional symbolism is attached to either positive or negative feelings towards the industrial past or present in the town. It can be connected to expressing strong positive sentiments of industrialism, expressed through leveraging industrial heritage in museums, tourist packages, etc. Likewise, negative sentiments of shame or trauma over industrial development can result in hiding or obliterating the industrial past.

Industry is undoubtedly a part of the semiotic landscape. It is defined as an area where public spaces bear visible inscriptions or signs made by deliberate human intervention and meaning making [17]. The term semiotic landscape was theoretically framed by human geographer Cosgrove [18] as a “way of seeing” or a “point of view”. It interprets space depending on geographical, social, economic, legal, cultural, and emotional circumstances and our practical uses of the physical environment, aesthetics, memories, and myths [17]. Symbols in the landscape can offer empirical evidence on how people make sense of their social and natural environment.

The semiotic landscape is interrelated with territorial identity formation and serves as a source for communities to create a “sense of place” [17]. Industrial identity is part of a broader concept of industrial culture as a place-based phenomenon embedded in the social interactions and particular lifestyles of past and present industrial communities [19]. It is a consequence of collective everyday experiences where workers share a way of life that transcends factories and is rooted in families and institutions [20]. Byrne [21] mentions the “industrial structure of feeling” as a similar concept for the way people live, the way they do things, and the sense of personal and collective identity. Importantly, industrial identity as part of a broader industrial culture is very enduring. It persists long after the material symbols (mines or factories) have disappeared and can co-exist with other, more dominant postindustrial cultures [20,21].

An industrial character is thus an important part of the local identity of (post)industrial cities. The industrial semiotic landscape is a tool with which we can establish how industrialism resonates within those communities. For example, if iconic industrial buildings are being conveyed as positive symbols in the urban landscape, this might indicate that the industrial past is being incorporated into popular imaging of local identity.

2.2. Reimaging and Rebranding Industry

Many reimaging strategies seek to give new meanings and new identities to (post)industrial cities. Place branding has become a tool for urban and regional regeneration, building a new image among residents and outsiders alike [22,23]. Industrial cities in particular are prone to reimaging, as they see their industrial image as a barrier to economic diversification and attracting non-industrial economic activities [4]. Many former industrial communities that want to make a “break with the past” on a symbolic level have opted for flagship projects. A typical example of this is Herleen, a former mining community in the Netherlands. The local authorities built the Moon Quarter, a futuristic district in the city center for shops and services. Thus, they replaced the image of a coalmining town with one that appeals to the new middle class [24]. The lesson of the story: The reimaging efforts are a socio-political struggle between the new working class, with its identity constructed around consumerism, and the old “manufacturing” working class [25].

Reimaging (post)industrial cities does not necessarily involve the destruction of industrial symbols. In some cases, industrial heritage can become a tool to promote new economic activities, especially tourism. A report from Spain shows how industrial cities are using European funding to strengthen their identity by protecting iconic industrial heritage and repurposing it for tourism [26]. From a historical and heritage perspective, this is more favorable than destroying or replacing industrial symbols with new and generic symbols of the post-industrial age. However, there is a risk that industrial heritage can become an agent of commodification, homogenization, and neoliberalism, especially if it is not embodied and experienced by local residents [3]. There are reports where such commodification of culture produced gentrification and further socio-spatial inequalities in the city [12,24].

Reimaging the industry then cannot be a top-down process. The symbols have to be re-produced by the local residents who interact with and live in the place. Simply put, the new projected image must correspond to the identity of the place [27]. These strategies have to be balanced between the possible negative associations of (de)industrialization and the different industrial imaginaries of local residents [28]. One possible way to strike such a balance is for the residents and local government to co-produce the industrial city transformation strategies [29]. In the Finnish industrial city of Pori, rebranding was a collaborative process in which local people were involved as active participants from start to finish. For example, residents drew on their industrial reality when they proposed the city’s own perfume (Eau de Pori) as the new brand, a humorous reference to the city’s characteristic odor coming from two nearby factories [28].

Industrial reimaging in a city can take many forms. Within the post-industrial paradigm, official discourses tend to favor non-industrial discourses and reduce industrial ones only to their aesthetic or touristic function [30]. However, this discrepancy can be problematic and potentially cause friction and resentment within communities.

3. Case Study Description: Velenje, Slovenia

The Slovenian territory experienced three waves of industrialization: The first at the transition from the 19th to the 20th century driven by coal; the second in the 1920s before the Great Depression driven by electricity; and the third, which was particularly pronounced, after World War II in the form of Fordist mass production driven by socialist ideology. The third wave brought industrial development to rural areas. The socialist goal was to spread industrialism and the proletarian class throughout the country. Smaller towns and completely rural areas began to industrialize, which is still a feature of industrialization today [31]. The waves of industrialization associated with the transformation and the path-dependent post-socialist economy have produced different types of industrial cities: (1) Socialist cities industrialized in the socialist era with industries successfully converted to the capitalist system (medium-sized machinery, electrical equipment, metal products), (2) new manufacturing cities either industrialized after the collapse of socialism or whose industrial development has nothing to do with their past, and (3) positively and negatively deindustrialized cities [32].

Velenje falls into the first category of transformed socialist towns and cities. In general, these are smaller towns located in peripheral areas away from major transport routes [33] and have one or two large factories where the local population works. They are characterized by low unemployment and favorable economic indicators. They are vulnerable due to their dependence on one or two companies and the volatile world economic conditions. They show their socialist egalitarian legacy with a homogeneous income structure, reliance on local labor, strong identity, trade union movements, and strong local political interest groups [31,34].

Our case study is Velenje, a medium-sized town in Slovenia (33,000 inhabitants). Its emergence is directly linked to coal mining for the largest Slovenian thermal power plant in the neighboring town of Šoštanj and later to the metalworking industry. In 1959, a common modern urban plan was drawn up, which laid the foundation for the modernist garden town with a high-quality residential environment (utopian socialist town). The town’s official name between 1981 and 1990 was Titovo Velenje (Tito’s Velenje), named after Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito. This was an honorary title awarded to only one town in each of Yugoslavia’s eight republics and autonomous regions that most consistently realized the ideas of self-management and the development of a socialist society.

The developing coal mining and industry opened up many employment opportunities. The population grew dramatically due to massive immigration, almost tripling between 1961 and 1991. After the collapse of socialism and Slovenia’s independence in 1991, Velenje managed a relatively successful transformation of its industries to a market economy [35]. Besides coal mining, the town specialized in the production of medium-technology machinery, electronics, and household appliances (Gorenje appliance company), which together employ over 60% of the town’s total labor force [34]. Today, Velenje has favorable socio-economic indicators, such as a low unemployment rate and low income inequality. Its successful transformation is also a consequence of state investments in the energy sector (thermal power plant and mining subsidies). The town is characterized by a deep-rooted mining, industrial, and labor tradition [36,37]. Recently, the environmental engineering sector has been growing as a result of the knowledge about coal mining and its negative impact on the environment [34,38].

4. Methods

We pursue our main objectives by examining the (visual) industrial semiotic landscape of the case study town of Velenje. The first specific objective is to uncover the collective industrial imagery of the residents and whether it has positive or negative connotations for them. To achieve this, we analyzed the semiotic landscape of the industry. We examined the urban landscape for signs and symbols of past and present industry. By analyzing these symbols, we hoped to understand and interpret the formation of a place-based industrial identity [39] by the local residents.

The analysis of the industrial landscape was conducted via a field study in which semiotic elements were identified and photographed. Each visual industrial symbol in the town was mapped. This was performed to identify people’s dominant discourse towards industry. We paid particular attention to how the visual symbol is spatially ‘emplaced’ [40]; in particular, whether it is shown in central display places (public squares, ‘elite’ places, etc.) or more backstage or in passing. For each visual industrial symbol, we determined its significance in relation to past and present industry, location, appearance and state of preservation, visibility in the landscape, and its function in relation to industrial heritage in questionnaire form (see Supplementary Material, File S1). To our knowledge, there is no typology of specifically industrial semiotics, so we drew on the typologies of industrial culture [19,20] and similar studies analyzing symbols [14,41] to identify six main elements of the industrial semiotic landscape:

- Industrial buildings, sculptures, and public open spaces.

- Heritage institutions and communal spaces (museums, collections, individual exhibitions).

- Tourism promotion (souvenirs, advertising, place-based consumption, guidebooks, tourist offers, attractions).

- Arts and culture (cultural events, creative reuse of abandoned buildings, public art, local bibliography).

- Names and emblems (geographical names, coats of arms, names of institutions, anthems).

- Collective actions (solidarity and community work).

We then conducted 33 short onsite interviews with randomly selected passers-by on the streets of Velenje to understand the residents’ attitudes towards industrial symbols and industrial development in general. The main question concerned the perceptions and memories of industry in the town and urban development in general. In particular, we wanted to discover the emotional attachment and narratives ascribed to industry and the town’s past development (see Supplementary Material, File S2 for the interview questions and basic interviewee information). The interviews served as complementary material to the mapping of industrial symbols. We wanted to reveal the industrial identity of the place and to add missing parts that could not be identified through the field research alone, particularly for non-visual symbols, such as collective actions, events, etc. The interviews were short and lasted up to 20 min on average. At the beginning of the interview, we asked about three dominant town symbols associated with industry, socialism, and future development. These symbols were used to observe people’s emotions and to determine their opinions about their past, present, and future industrial development. We took notes but did not record or transcribe the interviews. Each interviewer had to mark the recurring themes and questions that came up in the conversation. At the end, the interviewers rated the respondents’ emotions, either as positive, negative, or neutral attitudes towards the three dominant themes (see Supplementary Material, File S2). In the interview protocol, we followed the European code of conduct for research integrity, adopted in 2011.

The second specific objective is to determine how officials and policy makers see industry and how they want to portray and interpret it (i.e., policy discourses). To this end, we conducted a content analysis of ten official strategic documents ranging from general development strategies to more specific economic or social strategies (tourism, transport, welfare, etc.), which are accessible on the website of the Municipality of Velenje (Table 1). We performed a critical overview of the documents and analyzed whether the industry is interpreted in a positive (e.g., pride, opportunity, new development, etc.) or negative way (e.g., pollution, degradation, shame, etc.). Specifically, we were interested in analyzing the role and importance of industry for urban development and in making a comparison with other economic sectors (e.g., services, tourism, creative industries). The focus was also on identifying the perceived impacts of industry on other socio-ecological urban structures in policy documents (e.g., pollution, revitalization of degraded areas, living environment, collective actions). Our findings attempt to reveal how policy makers (re)image the industrial past and present and whether they want to either leverage it or hide from it.

Table 1.

Strategic documents of the Municipality of Velenje.

5. Industrial Semiotic Landscape of Velenje

This chapter presents the results of the analysis of the industrial landscape through a field study in which semiotic elements were identified and interpreted. These sections tell the story of how different visual and non-visual symbols represent and display past and present industry and indicate the residents’ industrial identity. The symbols were mapped, photographed, and described (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Industrial semiotic landscape of Velenje, with the locations of the mapped symbols.

5.1. Industrial Buildings, Sculptures, and Public Open Spaces

The material symbols of industrial and mining heritage are found in the built environment in the form of 7 sculptures, 10 residential and public buildings, 3 public open spaces, and 5 industrial sites. Most of these symbols were created in the first decades after World War II and are well placed, visible, maintained, preserved or restored, and communicated to visitors. They point to an enduring, explicitly positive, sometimes idealized image of the industrial past and present, conveyed mainly by the local authorities. None of the sculptures were removed or destroyed in the transitional period after 1991; all remained in place. In this respect, a very-well-preserved and maintained city center stands out: Tito Square with its sculptures. Among them is the statue of Tito, the largest of its kind in the world (Figure 2). The square is lined by public buildings built in 1959 according to the principles of modernism symbolizing the design of a modern industrial town under socialist rule [42]. It seems that industrial and socialist semiotics have been bundled into one coherent narrative.

Figure 2.

Tito Square featuring modernist public buildings and multistory residential blocks.

Some symbols are very recent and show the continuation of the industrial past and present being honored. A sculpture was erected in one of the roundabouts at the entrance to the town in 2009 in honor of coal mining and the 50th anniversary of the town, the largest of its kind in Slovenia. Of the public open spaces, the recreational parks and playgrounds that are spread throughout the town are of particular note. One example is the children’s playground ‘Miners’ Village’, built in 2014 and presenting the history of energy efficiency and the importance of the local energy source. In general, the monuments of the coal mining industry are somewhat idealized, especially those representing the continuity and growth of the town, which is quite uncertain due to the possible closure of the coal mine and the thermal power plant. Some existing buildings that were directly related to mining (e.g., the miners’ administration building, the towing house for the mining school students, the industrial mining high school) have been rebuilt, but the memory of their original use has been well preserved with informative signs.

5.2. Heritage Institutions and Communal Spaces

The industrial tradition in the museums around Velenje is widely represented by numerous collections, materials, exhibitions, and shows, especially in two heritage institutions: the Museum of Velenje and the Slovenian Coal Mining Museum. Mining and energy production dominate these permanent exhibitions. The proportion of exhibitions devoted to industry and socialism varies between the two museums. The Slovenian Coal Mining Museum portrays a sense of pride in its former industry and tells a narrative of the miners’ hardship and life in the town. In the Museum of Velenje, only a handful of exhibitions told the story of mining and industry between 2001 and 2014. On the other hand, every fourth temporary exhibition in the Slovenian Mining Museum between 2010 and 2017 was dedicated to the history of mining, which suggests a renewed interest in industrial history. In communal spaces, industrial heritage manifests itself indirectly through cultural programs, cultural heritage, and iconic architecture. The Dom kulture (House of Culture) Cultural Center, for example, is a typical modernist building, also hailed as the “cathedral of the new socialist order” [43], clearly dominating the townscape (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Dom kulture Cultural Center dominates the main town square.

The locations of the community spaces are well known to all the residents and are well-maintained and popular public places for socializing. Three community spaces stand out: (1) The Dom culture Cultural Center, a public cultural institution that offers cultural programs; (2) the Museum of Velenje, housed in a non-socialist/non-industrial Renaissance castle and featuring thematic exhibitions about the founding of the town; and (3) the Slovenian Coal Mining Museum, where visitors can ride down the shaft in the oldest mining lift, walk through the original mining shafts, and have a miner’s lunch in the deepest canteen in Slovenia.

In their interview answers, the residents were mostly positive about the industrial heritage and its presentation; although, again, industrial heritage is often associated with the legacy of socialism, as the beginning of industrialization and the founding of the modern city coincide with it. Some negative perceptions of industry can be found in narratives about the town’s history, mainly due to the earlier environmental degradation in the 1970s and 1980s caused by excessive air pollution. Nevertheless, the emotional symbols of the mining tradition remain very positive.

5.3. Tourism Promotion

Industrial identity is firmly present in the tourism development and promotion of Velenje and is strongly linked to the narrative of socialism. The industrial symbols are prominently featured in 5 tourist routes, 13 souvenirs, and 4 culinary products. The titles of the tourist routes are self-explanatory: “The Socialist Experience in Velenje”, “A Retro Walk in Velenje”, “In the Footsteps of Miners”, “Tales of Lost Villages”, and “A Walk through a Modernist City”. The most popular souvenir in the Velenje Tourist Information Center is a T-shirt with the inscription “Tito’s Velenje” and a red star. Other socialist souvenirs include a T-shirt with a socialist-era limerick “It’s wonderful to be young in our homeland” (a slogan from a popular socialist youth anthem), postcards with a commemorative picture of Tito and Tito’s monument in Velenje, and a magnet from Tito Square (Figure 4). For arriving tourists, the Tito statue is one of the motives for visiting the town.

Figure 4.

Velenje’s promotional T-shirt featuring the former president of Yugoslavia, Tito.

The most popular souvenirs from the mining industry include a candle holder made of coal, a miner’s lamp on a lump of coal, and a packed piece of coal. The children’s game “Nine times Velenje” introduces the heritage of coal mining and the urban development of the town. The heritage of mining and the former leather industry in the nearby town of Šoštanj are described in a series of children’s books with songs and stories, enhanced with a music CD for kids. The books and songs are very important for building the mining and industrial identity of the children in Velenje, as they all receive them as New Year’s gifts in the local schools.

The industrial and socialist heritage also manifests itself in culinary experiences. A local restaurant offers grilled meat on a spit called “Miner’s goulash”. The popular socialist-era-themed burger restaurant Nostalgija (Nostalgia) uses Yugoslav socialist iconography and offers the “lignite burger” (lignite is a local type of coal that was the basis for the development of coal mining) and the ”Maršal burger” (in reference to “Marshal”, the nickname of Josip Broz Tito).

5.4. Arts and Culture

Visual symbols of the town’s art and culture include the creative reuse of abandoned industrial buildings, public art, and the consumption of popular culture. Many industrial buildings have been repurposed and have become the subject of creative place-making. Stara pekarna, a former bakery in Velenje’s old town, was transformed into an art space for galleries and concerts in 2012, when Velenje was part of the European Capital of Culture. Since then, the space has been a visual arts gallery and a regular venue during the Kunigunda Festival of Young Cultures. Klasirnica, the former coal separation plant, is a huge building that was abandoned after the coal separation plant was no longer needed. During the Kunigunda Festival of Young Cultures in 2012, a group of artists painted what is probably Slovenia’s largest mural on the façade of the building. The artists drew their self-portraits, with one of them depicted as a proud coal miner. In both cases, the significance of the buildings is made clear by their positive attitude towards industrial heritage.

In addition to the Tito monument, there are other public artworks related to the town’s socialist and coal mining past, such as the statue of local economist and politician Nestl Žgank—founder of the modern town, its planner, coal mine director, and mayor—and the statue of the anonymous miner (Figure 5). These statues enjoy a higher status among the inhabitants of Velenje than the socialist statues in other towns in Slovenia, which is reflected in their diligent maintenance. Some local musicians have promoted Velenje’s industrial heritage in their work, most notably rap musician 6Pack Čukur, who depicts industrial buildings and communist statues as the town’s main landmarks in his music videos.

Figure 5.

Statue of an anonymous miner in the main town square.

In consumer and popular culture, an aura of the “pastness” is found in the retro names and visual imaginary of cafés and restaurants. This type of symbolism is prevalent in Velenje’s consumption venues and refers to the town’s industrial and socialist heritage through the use of red stars, former flags, retro slogans, miners’ iconography, etc. Short interviews reconfirmed that there is a common feeling of socialist nostalgia, bundled with feelings of pride of the industrial past.

5.5. Names and Emblems

Surprisingly, there are few geographical names directly linked to the industrial and mining tradition of Velenje and its surroundings, probably because industrial development has only been intense in the last 60 years or so. There are virtually no toponyms related to industry and mining, apart from a few references to mills and smelters. Velenje features the Miners’ Road (Rudarska cesta) and the Mine Road (Rudniška cesta). The nearby town of Šoštanj has a Factory Road (Tovarniška pot). Topographical names associated with industry and mining are related to today’s industrial and mining companies, such as the Velenje Coal Mine or the Gorenje appliance company. However, industrial symbols can also be found in the names of sports, educational, and cultural institutions. Of the 66 registered sports clubs in the municipality of Velenje, six bear names related to mining and industrial companies, such as the Miner (Rudar) Football Club or the Gorenje Velenje Handball Club. This also shows the local industries’ commitment to sponsor the sports clubs as a part of their social responsibility strategies.

The coat of arms of Velenje was chosen out of 300 proposals in an open tender in 1992. The semiology of the current coat of arms is very modernistic (Figure 6). The white tower rising above the old castle wall (shown in green) symbolizes the modernist history of Velenje and reinforces the idea of a newly built industrial town rising above the old feudal historical remains.

Figure 6.

Coat of Arms of the Municipality of Velenje (Source: www.velenje.si, accessed on 26 February 2022).

5.6. Collective Actions

The fusion of industrial and socialist identity is most clearly visible in the symbols of collective action. Pride in collective actions from the socialist era was one of the most common narratives expressed in the short interviews. Through them, we identified non-visual symbols of industrial and socialist values through solidarity and communal work. Velenje was built largely by shock workers, i.e., (semi)voluntary workers who dedicated their free time to building the town’s public infrastructure and raising the social standard of the entire community. Shock labor has itself become a symbol of collective action and is reflected today in community building actions, such as youth volunteering and the work of trade unions and NGOs [34]. It is often mentioned in various narratives about the founding of the town and as a symbol of the self-sacrifice of workers and their families for the good of the entire community. Only one interviewee had a negative sentiment towards socialist collective actions describing shock work as a ‘voluntary must’.

There are numerous organizations in Velenje with very enthusiastic and committed members, such as the largest local branch of the scout association in Slovenia, brass bands, etc. They often mention that volunteering is a result of their industrial and socialist identity and is inseparable from values, such as solidarity, tolerance, multiculturalism, mutual respect, comradery, and equality [34,44]. In the interviews, residents expressed a sense of belonging to these values, which symbolize the self-sacrificing and collective nature of the town’s residents. Shock work and volunteering have thus become a symbol for the working-class collective identity, combined with (mild) socialist nostalgia.

6. Role and Importance of Industry in Policy Discourses

In this chapter, we analyze how officials and policy makers view industry and how they want to portray and interpret it. We conducted a content analysis of official strategic documents ranging from general development strategies to more specific environmental or social strategies (tourism, transport, welfare, etc.). The results shed light on how policy makers (re)image the industrial past and present and whether they want to leverage it or hide from it.

The general development guidelines of the municipality are set out in the Strategic Development Document of the Municipality of Velenje (from 2008) and the subsequent Sustainable Urban Strategy for a Smart, Entrepreneurial, and Friendly Velenje 2025 (from 2015). Both documents clarify the vision of the municipality and the discursive symbolism it wishes to convey:

“…Velenje will be characterized by a well-developed economy based on the innovations of highly qualified experts, especially in the fields of research, design, and environmentally friendly and energy-efficient technologies. The appealing quality of living in terms of the friendliness and tolerance of citizens and environmental sustainability, the high quality of life in terms of the diversity of cultural and sporting activities…”

Even though the documents start their introductions with terms such as “socialist miracle” or “pioneering spirit”, the town’s industrial past, present, or future rarely express a positive connotation. In fact, it is difficult to deduce the industrial character of the town from the texts at all. There is no occurrence of the term industrial heritage. Individual industry-based development policies appear inconsistently and fragmentarily. They can be narrowed down to tourism activities (on the lakeside of degraded mining areas); environmental research and education; and the reuse of industrial buildings for creative and youth activities.

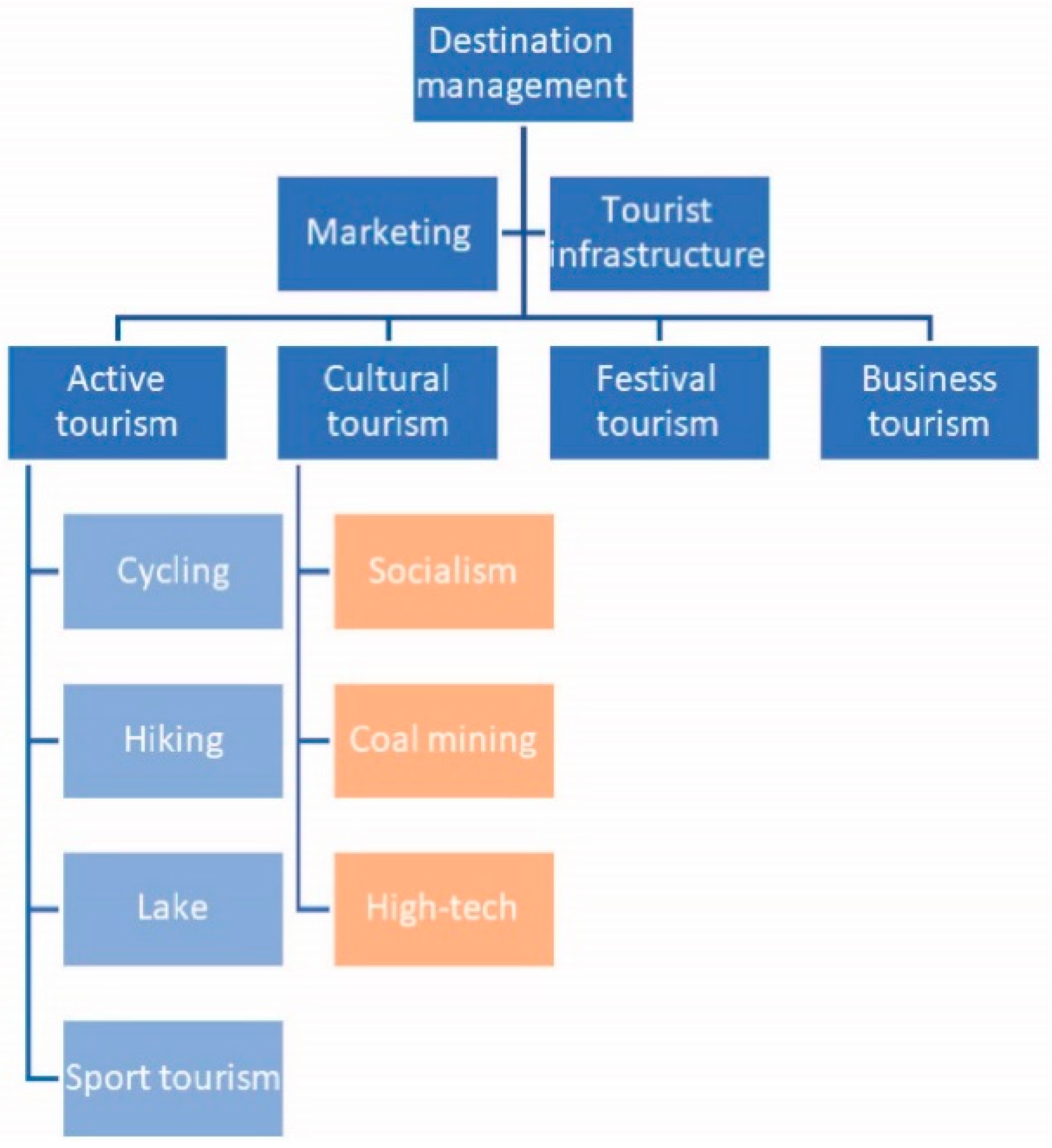

Among the other strategic documents expressing the industrial character and heritage of the town, the Tourism Development and Marketing Strategy in the Municipality of Velenje 2017–2021 stands out (see Figure 7). It is very different in its “mission” from the general vision of the town:

Figure 7.

Emphasizing socialism, coal mining, and high-tech companies as part of future tourism development in Velenje (taken from the Tourism Development and Marketing Strategy in the Municipality of Velenje 2017–2021, p. 63).

“We responsibly preserve the values of solidarity and comradery, which have become a rarity today and are often forgotten; we protect the memory of a time that has strongly influenced the image of Velenje and Slovenia as they are today, and we protect and interpret the heritage that comes from a time before us.”

The document adds that Velenje’s greatest attraction for domestic and foreign tourists is the town itself: The story of its origins, the recent history and development related to the heritage of coal mining, the well-preserved modernist architecture, monuments, and the technological heritage reflected today in successful local businesses. Unlike most other documents, the authors of the tourism marketing strategy are external experts who are not from Velenje. This was probably the decisive factor for the future possibilities of tourism development in the municipality to be interpreted in this way. With their outside perspective, the authors have succeeded in imaginatively weaving together socialism, coal mining, and high-tech entrepreneurship as the main symbols and pillars of tourism in Velenje.

The industrial tradition is hardly represented in the official documents, as the prevailing trend is towards post-industrial development and a consumerist society. However, the documents show that the emphasis is on social programs, the social inclusion of disadvantaged groups, and solidarity. This could be the result of the emergence of a collective consciousness during the period of industrial society. It could be a consequence of a socially oriented state as a whole and/or the structure of the Slovenian space, which is predominantly rural with small towns where personal ties between residents and workers are stronger than in large cities.

7. Discussion

The aim of this article is to examine how past and present industrial activities are interpreted by local people on the one hand and by policy makers on the other and whether there is a conflict between the two. An analysis of the industrial semiotic landscape in Velenje revealed that the industrial past and present are expressed mainly through visual symbols such as sculptures, most of which depict coal mining. Public places, such as the main square, are clean, well-maintained, and decorated with socialist-industrial iconography, suggesting positive connotations. The industrial tradition is also reflected in museums and exhibitions, where the mining and household appliance industries dominate over other industries. We detected a positive attitude towards industrial heritage and tourism promotion, e.g., in the form of mining souvenirs or innovative tourism packages. The analysis suggests that industry is firmly entrenched in the minds of the local people and manifested through emotional symbols across the town. The iconography (the description of symbols) of the socialist-industrial past is being used to portray this image to outsiders (visitors, tourists) and is a source of pride and economic gain for the local residents. The town is characterized by a deep-rooted mining, industrial, and working-class tradition that defines industrial culture with tacit knowledge, fundamental values, and norms, such as solidarity, intercultural coexistence, tolerance, mutual aid, and social equality. The legacy of a strong collective consciousness and local identity has been transformed into voluntary actions that are popular among local residents [45].

The industrial semiotic landscape in Velenje is well represented and interwoven with signs and symbols of socialism and modernism. The symbolic geography of this industrial town is riddled with remnants of the Yugoslav past that continue to shape and define the present. Industrialism in Velenje is inevitably linked to the socialist past and the origins of the modern city. This is why industry and the socialist past are represented through various symbols and are a matter of pride and collective identity for the inhabitants. Socialist nostalgia is a common phenomenon in post-socialist countries [46]. In Velenje, socialist nostalgia is passed on to the younger generations who did not experience socialism. Bars, youth clubs, and other places where young people meet are full of symbols with socialist and mining iconography. As Velikonja [46] notes, this socialist nostalgia is not so much a commercial niche or a political statement, but a retrospective utopia in which residents wish for a better world with values such as true friendship, more solidarity, and a fairer society. In a way, socialist and industrial nostalgia can be interpreted as a reaction of a more collective (industry-based) identity to a new, individualistic and consumerist identity.

However, in contrast to the prevailing identity of the local residents, the official identity politics seems to try to make a detour from both industrial and socialist narratives in the city. The official documents and policies predominantly follow the discourse of western post-industrial cities, for example by emphasizing the high quality of life through leisure and cultural activities. In this discourse, industry is associated and presented with impending deindustrialization and inferior socio-economic performance. In the discourse on urban shrinkage, industrial urban areas are often portrayed as economically disadvantaged and vulnerable to demographic shrinkage [47] or as resistant to change because their industrial specialization leads to negative path dependency in development [48]. We have found evidence that town officials inadvertently ascribe new discursive symbolism to industry in their strategies and policies and present an embellished urban imaginary to their audiences. In the process, new positive symbols (culture, high-tech services, etc.) emerge while the existing and traditional industry is “washed away”. We argue that the town leaders, under the influence of prevailing post-industrial discourses, have begun to promote a specific post-industrial urban imaginary to residents and outsiders alike.

These generic policy discourses emerged as a consequence of the construction of new territorial identities in order to enhance place attractiveness and economic growth [49]. Post-industrial economic policy discourse is often an attempt to relate a city or region to a globalization process and is sometimes referred to as a “thin identity”, which is related to a specific problem and is utilitarian, as opposed to a “thick identity”, which is normative and grounded in local culture and history [50]. In the case of Velenje, thin identity is reflected in the policy discourse emphasizing the service economy and the postindustrial structures, while the combined industrial-socialist identity of the residents is reflected as the thick identity. An empirical analysis of these reimaging efforts in five Swedish counties found that these policy discourses focus on outsiders’ perspectives and disregard internal place-based qualities and strengths [49]. These contradictions in development narratives can lead to potential conflicts, as described, for example, in the Norwegian industrial town of Odda, where the authorities pursued a more culture-based discourse of development and locals a more industrial one [51].

At the moment, no real conflict exists between the two imaginaries in Velenje: The industrial one of the local residents and the discursive post-industrial idea of the policy makers seem to coexist. The policy makers seem to play a dual role: In the policy discourse, they clearly favor the postindustrial semiotics, while at the local level, they invest resources to preserve the town’s industrial semiotic landscape. This duality also applies to the socialist semiotics: There is hardly any mention of it in the official policy discourse; however, the local authorities are diligent in maintaining socialist-era tangible (statues, public squares) and intangible symbols (names, references to collective actions). We suspect that maintaining industrial and socialist symbols is a way for local politicians to strengthen their position on the political left, where the majority of votes are found. In their “outward” communication though, they use completely different symbols to present the town as post-industrial and “more modern”. The role of political structures in interpreting and engaging with the socialist past and using it for tourism or identity-building purposes is a relevant topic that should be explored in future research.

This status quo could lead to an identity crisis, especially if the official policy discourse were to collide with the symbols of industrial identity in the future. However, the recently adopted tourism strategy might suggest that the town’s thin and thick identities are not necessarily antagonistic. The tourism strategy takes into account both industrial and socialist heritage and shows how to leverage it with other, more service-oriented activities, such as business and high-tech tourism. This document can serve as a good practical example for other industrial towns and cities that have been lost in the imported post-industrial discourses.

8. Conclusions

For our concluding thoughts, we would like to leave our specific case study and raise broader theoretical and practical concerns. The problem of reimaging and rebranding older industrialized places is indicative of a deeper struggle within post-industrial societies. The service economy provides the majority of jobs in the countries of the Global North, but industry remains very important in terms of economic output and its symbolic and cultural value. The positive influence of industrial culture in older industrial cities is expressed through neo-industrial strategies of flexible specialization, the knowledge economy, and fostering a pioneering spirit [52,53]. Industrialism shaped by a specific identity, culture, and values is still relevant to the idea of the “good city”, where collective well-being and a close-knit community are very important [54] and can be a source of social and other innovations [34]. There are numerous reports where expressions of industrial identity and culture are not considered valid or important in today’s society, for example in education [55] or creative activities [56]. This could mean that academic discourse is no different from other policy discourses and, in turn, neglects industrial identity as an ontological reality of many (post)industrial cities. It could also mean that integrating semiotics into political economy and developmental studies might be useful. Jessop [57] argues for integrating semiotic analysis into development studies to identify broader struggles between dominant hegemonic economic discourses (the “new economy”) and how they resonate in situ with the local populations.

The practical implication of this research is that (post)industrial cities should promote their niche assets derived from industrial heritage. We agree that the reimaging of industrial cities should be conducted in a co-creative, participatory way, involving the residents’ sense of place identity and attachment [13,28], but we propose to go even further. We suggest that tangible and intangible industrial heritage should not only be treated as symbols of the past and consumer goods for tourists and visitors. Rather, industrial symbols can become a reference point to create an alternative perception of a modern consumer society based on past industrial values, such as collective well-being, solidarity, and equality. Based on the findings of this research, official discourses in Velenje should find a balance between the strong industrial identity of the place and contemporary culture and creative industry-led strategies. The industry should neither be “washed away” nor treated as an object of commodification, but as a powerful tool to further strengthen the local identity and counteract the pitfalls of the contemporary consumer society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc12020049/s1, File S1 (with Table S1 of questions for mapping visual industrial symbols); File S2 (containing short interview questions and Table S2 containing the structure of respondents and their attitudes towards three dominant themes).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., P.K., P.G., J.K., P.P., J.T.; methodology, D.B., P.K., P.G., J.K., P.P., J.T.; investigation, D.B., P.K., P.G., J.K., P.P., J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, D.B., P.K., P.G., J.K., P.P., J.T.; visualization, D.B., P.K., P.G., J.K., P.P., J.T.; funding acquisition, D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme JPI Urban Europe with the project Bright Future (ENSUF call) and the Slovenian Research Agency (grant No. H6-8284). Authors D.B., P.G., J.K. and J.T. acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency research core funding Geography of Slovenia (P6-0101) and P.P. from the core funding Heritage on the Margins: New Perspectives on Heritage and Identity within and beyond the National (P5-0408).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bramwell, B.; Rawding, L. Tourism marketing images of industrial cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Conceptualizing City Image Change: The ‘Re-Imaging’ of Barcelona. Int. J. Tour. Space Place Environ. 2005, 7, 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanolo, A. The image of the creative city, eight years later: Turin, urban branding and the economic crisis taboo. Cities 2015, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilenska, V. City Branding as a Tool for Urban Regeneration: Towards a Theoretical Framework. Archit. Urban Plan. 2012, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Taboada, M.; Pancholi, S. Place Making for Knowledge Generation and Innovation: Planning and Branding Brisbane’s Knowledge Community Precincts. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardi, C. Cities for sale: Contesting city branding and cultural policies in Buenos Aires. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, C.J. Rebranding place “to build community”: Neighborhood branding in Buffalo, NY. Urban Geogr. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conolly, J.J. (Ed.) After the Factory: Reinventing America’s Industrial Small Cities; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vanolo, A. Cities are Not Products. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainikka, J.T. Reflexive identity narratives and regional legacies. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2014, 106, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A. Geographies of brands and branding. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 619–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonakdar, A.; Audirac, I. City Branding and the Link to Urban Planning: Theories, Practices, and Challenges. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, S. Trying to be attractive: Image building and identity formation in small industrial municipalities in Sweden. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2008, 4, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, P.J.M.; De Giosa, P. Conclusion: Feeling at Home in the City and the Codification of Urban Symbolism Research. In Cities Full of Symbols: A Theory of Urban Space and Culture; Nas, P.J.M., Ed.; Leiden University Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 283–292. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/21402 (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Blommaert, J. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes. Chronicles of Complexity; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šifta, M.; Chromý, P. The importance of symbols in the region formation process. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2017, 71, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A.; Thurlow, C. Introducing semiotic landscapes. In Semiotic Landscapes: Image, Text, Space; Jaworski, A., Thurlow, C., Eds.; Continuum: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E. Introduction to Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. In Landscape Theory; DeLue, R.Z., Elkins, J., Eds.; Routledge and University College Cork: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Görmar, F.; Harfst, J. Path Renewal or Path Dependence? The Role of Industrial Culture in Regional Restructuring. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bole, D. “What is industrial culture anyway?” Theoretical framing of the concept in economic geography. Geogr. Compass 2021, 15, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Industrial culture in a post-industrial world: The case of the North East of England. City 2002, 6, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHoose, K.; Hoekstra, M.; Bontje, M. Marketing the unmarketable: Place branding in a postindustrial medium-sized town. Cities 2021, 114, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, M.S. Iconic Architecture and Middle-Class Politics of Memory in a Deindustrialized City. Sociology 2020, 54, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M. Branding Cities: A Social History of the Urban Lifestyle Magazine. Urban Aff. Rev. 2000, 36, 228–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del pozo, P.B.; González, P.A. Industrial Heritage and Place Identity in Spain: From Monuments to Landscapes. Geogr. Rev. 2012, 102, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. Place branding: Are we any wiser? Cities 2018, 80, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, U.; Lemmetyinen, A.; Nieminen, L. Rebranding a “rather strange, definitely unique” city via co-creation with its residents. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2020, 16, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Stuetzer, M.; Obschonka, M.; Thompson, P. Historical industrialisation, path dependence and contemporary culture: The lasting imprint of economic heritage on local communities. J. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 21, 841–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorius, B.; Manz, K. Beyond the City of Modernism: A counter-narrative of industrial culture. GeoScape 2018, 12, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bole, D.; Kozina, J.; Tiran, J. The socioeconomic performance of small and mediumsized industrial towns: Slovenian perspectives. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2020, 28, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bole, D.; Kozina, J.; Tiran, J. The variety of industrial towns in Slovenia: A typology of their economic performance. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2019, 46, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goluža, M.; Šubic-Kovač, M.; Kos, D.; Bole, D. How the State Legitimizes National Development Projects: The Third Development Axis Case Study, Slovenia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2021, 61, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, J.; Bole, D.; Tiran, J. Forgotten values of industrial city still alive: What can the creative city learn from its industrial counterpart? City Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipan, P. Moč in ranljivost velenjskega gospodarstva. In Velenje, Industrijsko Mesto v Preobrazbi; Bole, D., Ed.; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, J. Vrednote industrijskega mesta v postsocialističnem kontekstu. In Velenje, Industrijsko Mesto v Preobrazbi; Bole, D., Ed.; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiran, J.; Bole, D.; Kozina, J. Industrial culture as an agent of social innovation: Reflections from Velenje, Slovenia. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrekar, A.; Breg Valjavec, M.; Polajnar Horvat, K.; Tiran, J. The Geography of Urban Environmental Protection in Slovenia: The Case of Ljubljana. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2020, 59, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowntree, L.B.; Conkey, M.W. Symbolism and the cultural landscape. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollon, R.; Scollon, S.W. Discourses in Place. Language in the Material World; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kossak, F.; Damayanti, R. Urban Symbols: The Understanding and Reading of Urban Spaces by Young Adults in Indonesian Kampungs. Spaces Flows Int. J. Urban Extra Urban Stud. 2015, 6, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kumer, P. Znaki in simboli socializma in industrije v Velenju. In Velenje, Industrijsko Mesto v Preobrazbi; Bole, D., Ed.; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poles, R. Z radirko skozi mesto: Kaj je še ostalo od mesta moderne? In Velenje, Industrijsko Mesto v Preobrazbi; Bole, D., Ed.; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ograjenšek, I.; Cirman, A. Internal City Marketing: Positive Activation of Inhabitants through Supported Voluntarism. Econviews 2015, 28, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Tiran, J.; Bole, D.; Gašperič, P.; Kozina, J.; Kumer, P.; Pipan, P. Assessing the social sustainability of a small industrial town: The case of Velenje. Geogr. Vestn. 2019, 91, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikonja, M. Lost in Transition: Nostalgia for Socialism in Post-socialist Countries. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2009, 23, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2018, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R. Locked in Decline? On the Role of Regional Lock-ins in Old Industrial Areas. In The Handbook of Evolutionary Economic Geography; Boschma, R., Martin, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010; pp. 450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, L.A. Using the Past to Construct Territorial Identities in Regional Planning: The Case of Mälardalen, Sweden. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, K. Rescaling Regional Identities: Communicating Thick and Thin Regional Identities. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 2009, 9, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, J.; Ellingsen, W.; Hidle, K. A Crisis of definition: Culture versus industry in Odda, Norway. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2013, 95, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Wust, A.; Nadler, R. Conceptualizing industrial culture. GeoScape 2018, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pipan, T. Neo-industrialization models and industrial culture of small towns. GeoScape 2018, 12, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, J.; Shaw, K. What next for the creative city? City Cult. Soc. 2014, 5, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areschoug, S. Rural Failures. Boyhood Stud. 2019, 12, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A.; Gibson, C. Blue-Collar Creativity: Reframing Custom-Car Culture in the Imperilled Industrial City. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 2705–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Critical semiotic analysis and cultural political economy. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2004, 1, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).