Physical Activity as a Tool for Social Inclusion in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Adults (age ≥ 18) with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis (PwMS). Studies including mixed populations were eligible only when separate results for PwMS were reported.

- Intervention: Any form of PA, exercise, adapted exercise, recreational activities, or lifestyle PA. Studies were eligible if they examined social barriers (e.g., stigma, lack of support), social facilitators (e.g., peer support, group settings), or social consequences (e.g., identity change, social participation) related to PA.

- Comparator: Any comparator (e.g., control group, wait-list, baseline measurements, alternative intervention) or none, as appropriate for the study design.

- Outcomes: Eligible studies reported qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods data on social dimensions of PA. To improve reproducibility and conceptual clarity, social constructs were explicitly operationalized as follows:

- ○

- Social support: perceived or received encouragement, companionship, or assistance (peers, family, healthcare professionals, community members).

- ○

- Stigma: enacted stigma (discrimination, negative attitudes) and internalized stigma (self-identification with negative stereotypes such as “too sick to exercise”).

- ○

- Social identity: perceptions of oneself in a social context, including shifts toward “exerciser”, “athlete” or “capable person”.

- ○

- Social participation/inclusion: involvement in community activities, group programs, classes; perceived belonging and acceptance.

- Study Designs: eligible study designs included qualitative studies, quantitative observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort), randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized intervention studies, and mixed-methods studies.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

("multiple sclerosis"[MeSH Terms] OR "multiple sclerosis"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("physical activity"[Title/Abstract] OR exercise [Title/Abstract] OR sport [Title/Abstract]) AND ("social barriers"[Title/Abstract] OR "social support"[Title/Abstract] OR stigma [Title/Abstract] OR "social participation"[Title/Abstract] OR identity [Title/Abstract])

TITLE-ABS-KEY (("multiple sclerosis") AND ("physical activity" OR exercise OR sport) AND ("social barriers" OR "social support" OR stigma OR "social participation" OR identity))

TS = ("multiple sclerosis") AND TS= ("physical activity" OR exercise OR sport) AND TS = ("social barriers" OR "social support" OR stigma OR "social participation" OR identity)

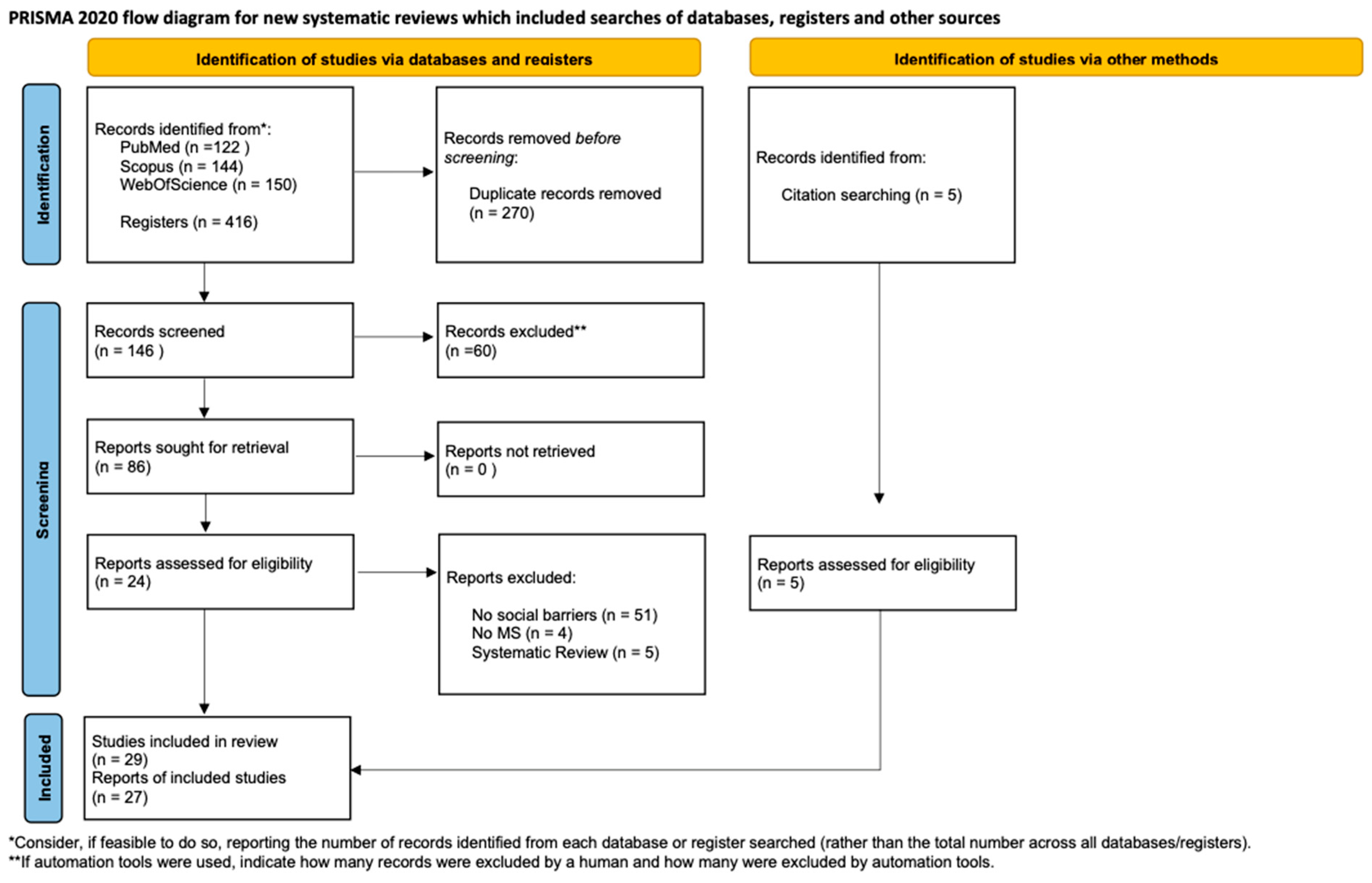

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Items

2.6. Risk-of-Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.7. Thematic Analysis Procedures

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Interpretation of Risk-of-Bias Findings

| Study | Philosophical Perspective | Methodology Congruence | Data Collection | Data Analysis | Researcher Reflexivity | Participant Voice | Ethical Approval | Conclusions Supported | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [12] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [6] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [34] | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Moderate |

| [36] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [11] | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Moderate |

| [20] | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Moderate |

| [13] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [16] | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Moderate |

| [39] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| [46] | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| Study | Research Question | Population Defined | Participation Rate | Exposure Measured | Outcome Measured | Confounders | Statistical Analysis | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | + | + | ? | + | + | ? | + | Low |

| [8] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | Low |

| [9] | + | + | ? | + | + | ? | + | Moderate |

| [37] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Low |

| [40] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | Low |

| [41] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | Low |

| [14] | + | ? | ? | + | + | ? | + | Moderate |

| Study | Randomization | Deviations | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement | Selective Reporting | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | ? | + | + | + | + | Low |

| Study | Clear RQ | Rationale | Integration | Interpretation | Data Quality | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | + | + | ? | + | + | Moderate |

| [21] | + | ? | ? | + | + | Moderate |

| [42] | + | + | + | + | + | Low |

| [43] | + | + | ? | + | + | Moderate |

3.4. Thematic Synthesis

3.4.1. Theme 1: The Multidimensional Nature of Social Barriers to PA

3.4.2. Theme 2: Physical Activity as a Mechanism for Social Inclusion

3.4.3. Theme 3: The Role of Theoretical Frameworks in Explaining Social Change

3.4.4. Conceptual Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Peer Support as a Central Social Mechanism

4.2. The Role of Knowledgeable Professionals

4.3. Identity Transformation and Psychological Change

4.4. Theoretical Integration: Social Cognitive and Socio-Ecological Perspectives

4.5. Cultural, Structural, and Severity-Related Considerations

4.6. Integration of Quantitative Findings and Effect Sizes

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Practice and Research

6.1. Clinical and Practical Implications

6.2. Research Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| PwMS | People with Multiple Sclerosis |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| PWB | Psychological Well-Being |

| HCPs | Healthcare Professionals |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| AF | Aquafitness |

References

- Compton, A.; Coles, A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008, 372, 1502–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Amato, M.P.; DeLuca, J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: Clinical management, MRI, and therapeutic avenues. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgas, U.; Stenager, E.; Ingemann-Hansen, T. Multiple sclerosis and physical exercise: Recommendations for the application of resistance-, endurance- and combined training. Mult. Scler. 2009, 14, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motl, R.W.; Pilutti, L.A. The benefits of exercise training in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensari, I.; Motl, R.W.; Pilutti, L.A. Exercise training improves depressive symptoms in people with multiple sclerosis: Results of a meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 76, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraclas, E.; Merlo, A.; Lynn, J.; Lau, J.D. Perceived facilitators, needs, and barriers to health related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative investigation. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Pilutti, L.A.; Hicks, A.L.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Fenuta, A.M.; MacKibbon, K.A.; Motl, R.W. Effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health-related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review to inform guideline development. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1800–1828.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, B.; Cederberg, K.L.J.; Huynh, T.L.; Silic, P.; Jones, C.D.; Feasel, C.D.; Sikes, E.M.; Baird, J.F.; Silveira, S.L.; Sasaki, J.E.; et al. Social Cognitive Theory variables as correlates of physical activity in fatigued persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 57, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaren, R.E.; Motl, R.W.; Dlugonski, D.; Sandroff, B.M.; Pilutti, L.A. Objectively quantified physical activity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnett-Hopkins, D.; Adamson, B.; Rougeau, K.; Motl, R.W. People with MS are less physically active than healthy controls but as active as those with other chronic diseases: An updated meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2017, 13, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, N.M.; McPherson, K.M.; Schluter, P.; Taylor, D.; Leete, M.; Kolt, G.S. Exploring the facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crank, H.; Carter, A.; Humphreys, L.; Snowdon, N.; Daley, A.; Woodroofe, N.; Sharrack, B.; Petty, J.; Saxton, J.M. Qualitative Investigation of Exercise Perceptions and Experiences in People with Multiple Sclerosis Before, During, and After Participation in a Personally Tailored Exercise Program. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann-Lorenz, K.; Wienert, J.; Streber, R.; Motl, R.W.; Coote, S.; Heesen, C. Long-term physical activity in people with multiple sclerosis: Exploring expert views on facilitators and barriers. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanner, E.A.; Block, P.; Christodoulou, C.C.; Horowitz, B.P.; Krupp, L.B. Pilot study exploring quality of life and barriers to leisure-time physical activity in persons with moderate to severe multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Health J. 2008, 1, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Riley, B.; Wang, E.; Rauworth, A.; Jurkowski, J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: Barriers and facilitators. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plow, M.A.; Resnik, L.; Allen, S.M. Exploring physical activity behaviour of persons with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative pilot study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 1652–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokryszko-Dragan, A.; Marschollek, K.; Chojko, A.; Karasek, M.; Kardyś, A.; Marschollek, P.; Gruszka, E.; Nowakowska-Kotas, M.; Budrewicz, S. Social participation of patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018; Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, B.; Wyatt, N.; Key, L.; Boone, C.; Motl, R.W. Results of the MOVE MS Program: A Feasibility Study on Group Exercise for Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.; Kitchen, K.; Nicoll, K. Barriers and Facilitators Related to Participation in Aquafitness Programs for People with Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2012, 14, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Twardzik, E.; Meade, M.A.; Peterson, M.D.; Tate, D. Social Participation Among Adults Aging with Long-Term Physical Disability: The Role of Socioenvironmental Factors. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 145S–168S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, S.; Gallagher, S.; Msetfi, R.; Larkin, A.; Newell, J.; Motl, R.W.; Hayes, S. A randomised controlled trial of an exercise plus behaviour change intervention in people with multiple sclerosis: The step it up study protocol. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, V.; Gajofatto, A.; Mazzi, M.A.; Gobbin, F.; Busch, I.M.; Ghellere, A.; Klonova, A.; Rudi, D.; Vitali, F.; Schena, F.; et al. A Bio-Psycho-Social Co-created Intervention for Young Adults with Multiple Sclerosis (ESPRIMO): Rationale and Study Protocol for a Feasibility Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 598726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Four, E.; Ratel, S.; Peytavin, M.; Aubreton, S.; Taithe, F.; Coudeyre, E. Évaluation des freins à la pratique de l’activité physique chez les patients porteurs d’une sclérose en plaques, étude qualitative à partir d’entretiens semi-dirigés. Lettre Med. Phys. Readapt. 2013, 29, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, W.; Dechow, A.-S.; Patra, S.; Heesen, C.; Gold, S.M.; Schulz, K.-H. Changes of Motivational Variables in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in an Exercise Intervention: Associations between Physical Performance and Motivational Determinants. Behav. Neurol. 2015, 2015, 248193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Brown, T. Exploring the perceived influence of a supervised group exercise programme on the psychological and physical wellbeing of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 2840–2847. [Google Scholar]

- Latinsky-Ortiz, E.M.; Strober, L.B. Keeping it together: The role of social integration on health and psychological well-being among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e2359–e2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulligan, H.; Treharne, G.J.; Hale, L.A.; Smith, C. Combining Self-help and Professional Help to Minimize Barriers to Physical Activity in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Trial of the “Blue Prescription” Approach in New Zealand. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2013, 37, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, N.; Gallagher, S.; Msetfi, R.M.; Hayes, S.; Motl, R.W.; Coote, S. Experiences of people with multiple sclerosis participating in a social cognitive behavior change physical activity intervention. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023, 39, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, C.; Haag, C.; Polhemus, A.; Haile, S.R.; Sylvester, R.; Kool, J.; Gonzenbach, R.; Von Wyl, V. Exploring the Major Barriers to Physical Activity in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: Observational Longitudinal Study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 11, e52733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.L.; Motl, R.W. Do Social Cognitive Theory constructs explain response heterogeneity with a physical activity behavioral intervention in multiple sclerosis? Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019, 15, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.L.; Richardson, E.V.; Motl, R.W. Social cognitive theory as a guide for exercise engagement in persons with multiple sclerosis who use wheelchairs for mobility. Health Educ. Res. 2020, 35, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.M.; Fitzgerald, H.J.M.; Whitehead, L. How people with multiple sclerosis experience the influence of nutrition and exercise on disease activity and symptoms: A qualitative study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 43, 102217. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.; Fazakarley, L.; Thomas, P.W.; Collyer, S.; Brenton, S.; Perring, S.; Scott, R.; Thomas, F.; Thomas, C.; Jones, K.; et al. Mii-vitaliSe: A pilot randomised controlled trial of a home gaming system (Nintendo Wii) to increase activity levels, vitality and well-being in people with multiple sclerosis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteneck, G.G.; Harrison-Felix, C.L.; Mellick, D.C.; Brooks, C.A.; Charlifue, S.B.; Gerhart, K.A. Quantifying environmental factors: A measure of physical, attitudinal, service, productivity, and policy barriers. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.J.; Goverover, K.; Politis, A.; Gutenbrunner, C. Social Support and Shared Experiences in Multimodal Agility-Based Exercise Training for People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study. Mult. Scler. J. 2024, 30, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Elkhalii-Wilhelm, S.; Sippel, A.; Riemann-Lorenz, K.; Kofahl, C.; Scheiderbauer, J.; Arnade, S.; Kleiter, I.; Schmidt, S.; Heesen, C. Experiences of persons with Multiple Sclerosis with lifestyle adjustment—A qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, N.; Poursafa, A.; Khazaali, K.; Rostami, H.; Jamshidian, E.; Mohammadi, Z.; Kamali, F.; Bahrani, N. Investigating Environmental Barriers Affecting Participation in Patient with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Rehabil. 2020, 21, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morghen, S.E.; W, M.R. Pilot study of social cognitive theory variables as correlates of physical activity among adolescents with pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 42, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šilić, P.; Jeng, B.; Jones, C.D.; Huynh, T.L.T.; Duffecy, J.; Motl, R.W. Physical activity and social cognitive theory variables among persons with multiple sclerosis and elevated anxiety. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2023, 25, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieff, S.G.; Wilson, J.; Kim, M.; Tierney, P.; Guedes, C.M. Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines through Community-Based Events: The Case of Sunday Streets. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Becker, H.; Stuifbergen, A. Comparing Health Promotion and Quality of Life in People with Progressive Versus Nonprogressive Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2020, 22, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults (≥18) with clinically confirmed MS (PwMS) | Studies on other neurological populations or mixed populations without separate analysis for PwMS |

| Intervention/Phenomenon | Any PA, exercise, sport; social barriers/facilitators | Studies without a social component; solely pharmacological interventions |

| Comparator/Context | Any comparator or context | No exclusion based on comparator |

| Outcomes | Social outcomes (support, inclusion, stigma, identity) | Solely clinical, biological, or non-social psychological outcomes |

| Study Designs | Qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods, RCTs | Systematic reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, non-peer-reviewed literature, non-English publications |

| Study | Study Design | Population | Intervention/Phenomenon | Key Social Findings | Effect Size (ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | Feasibility | PwMS (n = 33) | MOVE MS group program | Strong peer interaction; improved social identity | —(qualitative) |

| [30] | Qualitative | PwMS | Aqua fitness (AF) | Universality; reduced stigma; environmental barriers | — |

| [31] | Quantitative | Adults w/disability | Social participation factors | Socioenvironmental predictors strongest | r = 0.32 (reported) |

| [32] | RCT Protocol | PwMS | Step It Up (SCT-based) | Baseline data: social factors relevant | —(protocol) |

| [12] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 19) | Tailored exercise | Peer support + knowledgeable HCPs | — |

| [33] | Protocol | Young PwMS | ESPRIMO intervention | Baseline context on stigma | — |

| [6] | Qualitative | PwMS | HRQoL facilitators | Social support essential | — |

| [34] | Qualitative | PwMS | PA barriers | Social + psychological barriers | — |

| [35] | Mixed-Methods | PwMS (n = 67) | Motivation + PA | Social support predicts PA | r = 0.41 (reported) |

| [8] | Cross-sectional | PwMS (n = 146) | SCT variables | Support correlates with light PA | β = 0.27; p < 0.05 |

| [36] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 15) | Adapted rock climbing | Enhanced social identity + belonging | — |

| [11] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 21) | Barriers/facilitators | Environmental inaccessibility key | — |

| [10] | Meta-analysis | PwMS | PA levels vs. controls | PwMS less active globally | Included for contextual quantitative comparison, not as primary evidence |

| [9] | Quantitative | PwMS | Objective PA | PA influenced by social context | —(insufficient data) |

| [37] | Longitudinal | PwMS | Social integration | Higher social integration = better health | β = 0.34 |

| [38] | Trial | PwMS (n = 18) | Blue Prescription | Combined support reduces barriers | d = 0.36 (calculated) |

| [20] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 10) | PA experiences | Social influences on PA | — |

| [21] | Mixed-Methods | PwMS | Social participation | Multiple social dimensions explored | — |

| [13] | Qualitative | PwMS and HCPs (n = 32) | HCP roles | HCP support crucial for adherence | — |

| [16] | Qualitative | Disabilities | Environmental barriers | Attitudinal obstacles significant | — |

| [39] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 19) | SCT-based PA | Positive identity shifts | — |

| [40] | Observational | PwMS | Barriers (BHADP) | Self-efficacy reduces barriers | r = −0.29 |

| [41] | Secondary analysis | PwMS (n = 48) | SCT + PA | SCT explains heterogeneity | —(insufficient for ES) |

| [42] | Mixed-Methods | Wheelchair PwMS (n = 26) | SCT-guided | Social support essential | — |

| [43] | Mixed-Methods | PwMS (n = 25) | Community yoga | Improved social connectedness | — |

| [44] | RCT | PwMS (n = 30) | Wii home-based | Social well-being improved | η2 = 0.21 |

| [14] | Cross-sectional | Moderate-severe MS (n = 48) | Barriers to PA | Social + environmental barriers | — |

| [45] | Methodological | Disabilities | Barrier measure | Developed social barrier tool | — |

| [46] | Qualitative | PwMS (n = 10) | Multimodal exercise | Strong group support | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marzoli, F.; Cardinali, L.; Di Pinto, G.; Campanella, M.; Colombo, A.; Ferrari, D.; Marcelli, L.; Silvestri, F.; De Giorgio, A.; Velardi, A.; et al. Physical Activity as a Tool for Social Inclusion in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Evidence. Sports 2026, 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010025

Marzoli F, Cardinali L, Di Pinto G, Campanella M, Colombo A, Ferrari D, Marcelli L, Silvestri F, De Giorgio A, Velardi A, et al. Physical Activity as a Tool for Social Inclusion in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Evidence. Sports. 2026; 14(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarzoli, Federica, Ludovica Cardinali, Gianluca Di Pinto, Matteo Campanella, Andrea Colombo, Dafne Ferrari, Lorenzo Marcelli, Fioretta Silvestri, Andrea De Giorgio, Andrea Velardi, and et al. 2026. "Physical Activity as a Tool for Social Inclusion in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Evidence" Sports 14, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010025

APA StyleMarzoli, F., Cardinali, L., Di Pinto, G., Campanella, M., Colombo, A., Ferrari, D., Marcelli, L., Silvestri, F., De Giorgio, A., Velardi, A., Curzi, D., & Guidetti, L. (2026). Physical Activity as a Tool for Social Inclusion in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Evidence. Sports, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010025