Table Tennis as a Tool for Physical Education and Health Promotion in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria for Study Selection

2.2. Search Strategy

- ERIC (“table tennis,” OR “ping-pong,”) AND “physical education” OR “primary” OR “secondary” OR “university”.

- PubMed = (((“table tennis” OR “pigpong”) AND (“physical education”)) AND (“primary” OR “secondary” OR “university”)) Filters: Adaptive Clinical Trial, Case Reports, Classical Article, Clinical Study, Clinical Trial, Clinical Trial Protocol, Clinical Trial, Phase I, Clinical Trial, Phase II, Clinical Trial, Phase III, Clinical Trial, Phase IV, Controlled Clinical Trial, Multicenter Study, Observational Study, Randomized Controlled Trial, Twin Study, Validation Study, English, Spanish, Humans, Female, Male, Child: birth–18 years, Child: 6–12 years, Adolescent: 13–18 years, Adult: 19+ years, Young Adult: 19–24 years, Exclude preprints.

- ScienceDirect ((“table tennis,” OR “ping-pong,”) AND (“physical education”)).

- SCOPUS TITLE-ABS-KEY (((“table tennis” OR “ping-pong”) AND (physical AND education) AND (“primary” OR “secondary” OR “university”) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Spanish”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (EXACTKEYWORD, “Table Tennis”)).

- SPORTDiscus ALL = ((“table tennis,” OR “ping-pong”) AND (“physical education”))

- Web of table tennis OR ping-pong (Title) and physical education (All Fields) and primary or secondary or university (All Fields) and Article (Document Types) and English or Spanish (Languages) and Article (Document Types) and All Open Access (Open Access).

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias

2.5. Quality Assessment of Studies Included

3. Results

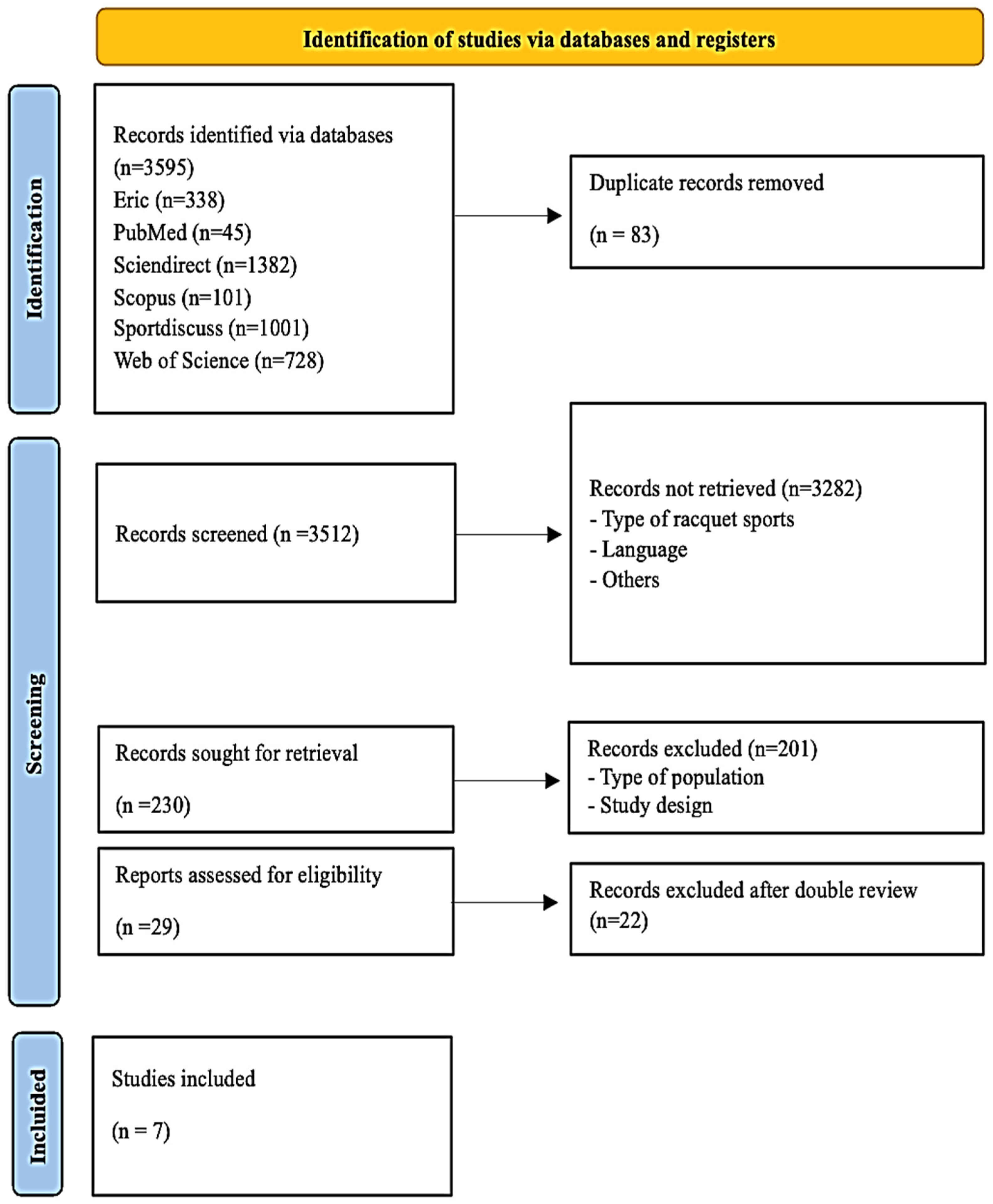

3.1. Main Search

3.2. Results of Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ennis, C.D. Physical Education Curriculum Priorities: Evidence for Education and Skillfulness. Quest 2011, 63, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.; Chey, W.S.; Kim, I.; Tsuda, E.; Ko, B.; Deglau, D.; Cho, K. An Analysis of Physical Education and Health Education Teacher Education Programs in the United States. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2024, 43, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Casado-Berrocal, M.; Heras-Bernardino, C.; Herrán Álvarez, I. Análisis y reflexión sobre el nuevo currículo de educación física Analysis and reflection on the new physical education curriculum. Rev. Española De Educ. Física Y Deportes 2022, 436, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Beni, S.; Fletcher, T.; Ní Chróinín, D. Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature. Quest 2017, 69, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlček, P.; Bailey, R.; Vašíčková, J.; Scheuer, C. Physical education and health enhancing physical activity—A European perspective. Int. Sports Stud. 2021, 43, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhr, K. Table tennis in secondary schools (part 2). Br. J. Phys. Educ. 1998, 28, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bechar, I.; Grosu, E.F. An Applicable Physical Activity Program Affecting Physiological and Motor Skills: The Case of Table Tennis Players Participating in Special Olympics (SO). Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 209, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkim, M.; Akyol, B. Effect of Table Tennis Training on Reaction Times of Down-syndrome Children. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 6, 2399–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraoka, E.; Yotsumoto, E. The Educational Value and Implementation Challenges of Teaching Table Tennis in Physical Education. Strategies 2024, 37, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Alonso, D.; Pérez Pueyo, A.; Méndez Giménez, A.; Fernandez Río, F.J.; Prieto Saborit, J.A. Análisis del desarrollo curricular de la Educación Física en la Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria: Comparación de los currículos autonómicos (Analysis of curriculum development of Physical Education in Secondary Education: Comparison of regional curricula). Retos 2016, 2041, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.; Victoria, S. El tenis de mesa en educación primaria y secundaria. Propuesta tomo la iniciativa con mi saque. Lect. Educ. Física Y Deportes 2010, 15, 150. Available online: https://efdeportes.com/efd150/el-tenis-de-mesa-tomo-la-iniciativa-con-mi-saque.htm (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- González-Devesa, D.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Pintos-Barreiro, M.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Benefits of Table Tennis for Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Roh, W.; Lee, Y.; Yim, S. The Effect of a Table Tennis Exercise Program With a Task-Oriented Approach on Visual Perception and Motor Performance of Adolescents With Developmental Coordination Disorder. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2024, 131, 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francová, L. The level of physical and social skills after completion of the training program for children aged 9-11. Acta Gymnica 2014, 44, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Tsai, C.L.; Lo, S.Y.; Cheng, Y.W.; Liu, Y.J. A racket-sport intervention improves behavioral and cognitive performance in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Tsuda, E.; Oh, D. School Sports Club in South Korea: Supporting Middle School Students’ Physical Activity Engagement and Social-Emotional Development in Schools. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2023, 94, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J.; Ren, Z.; Li, H.; Kim, H. The influence of a table tennis physical activity program on the gross motor development of Chinese preschoolers of different sexes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, İ.; Şen, M. The effect of basic table tennis training on some physical and physiological characteristics of children. Adv. Health Exerc. 2024, 4, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Biernat, E.; Buchholtz, S.; Krzepota, J. Eye on the ball: Table tennis as a pro-health form of leisure-time physical activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horníková, H.; Doležajová, L.; Zemková, E. Playing table tennis contributes to better agility performance in middle-aged and older subjects. Acta Gymnica 2018, 48, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Ara, I.; Toro, V.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Benefits of Regular Table Tennis Practice in Body Composition and Physical Fitness Compared to Physically Active Children Aged 10–11 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu Bozkurt, T.; Bozkurt, E.; Olgun, U. The relationship between table tennis athletes’ attitudes towards sports and academic achievement. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Sci. Res. 2023, 8(24), 2847–2860. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, G.; Shea, C.; Lewthwaite, R. Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Ge, H.; Liu, L.; Jing, X. Influence of functional training on teaching table tennis to college students. Rev. Bras. De Med. Do Esporte 2023, 29, e2022_0720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, J.; Becerra-Patiño, B.; Padli, P. Exploring the impact of eye-hand coordination on backhand drive stroke mastery in table tennis regarding gender, height, and weight of athletes. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2023, 23, 2710–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, A. Science and the major racket sports: A review. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 707–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Faber, I.R.; Visscher, C.; Hung, T.M.; De Vries, S.J.; Nijhuis-Vandersanden, M.W.G. Higher-level cognitive functions in Dutch elite and sub-elite table tennis players. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljaafreh, O.J. Measuring the Level of Knowledge of the International Law of Table Tennis Among Physical Education Teachers in Al-Karak. Sport I Tur. Srod. Czas. Nauk. 2024, 7, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Sherrington, C.; Maher, C.G. Evidence for physiotherapy practice: A survey of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Aust. J. Physiother. 2002, 48, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldawlatly, A.; Alshehri, H.; Alqahtani, A.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Dammas, F.; Marzouk, A. Appearance of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome as research question in the title of articles of three different anesthesia journals: A pilot study. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2018, 12, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Bruun Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.M.; Sullivan, F.; Murray, E.; Jolly, B. Critical appraisal checklist for an article on an educational intervention. BMJ. 1999, 318, 1265–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.M.; Sullivan, F.; Murray, E.; Jolly, B. Evidence-based education: Development of an instrument to critically appraise reports of educational interventions. Med. Educ. 1999, 33, 890–893. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00479.x (accessed on 3 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, M.; Stillwell, J.; Byars, A. Activity preferences of middle school phisycal education. Phys. Educ. 2001, 58, 26–29. Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA73889441&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00318981&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E7f311bed&aty=open-web-entry (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Hoffmann, D.; Brixius, K.; Vogt, T. Racket sports teaching implementations in physical education—A status quo analysis of German primary schools. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 867–873. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, W.; Lu, M.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P. Social-Ecological Analysis of the Factors Influencing Shanghai Adolescents’ Table Tennis Skills: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, G. Round table tennis for the young: A playground for uniting different cultures. N. Z. J. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1987, 20, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, S. Adapting Equipment For Teaching Object Control Skills. Phys. Educ. 2013, 27, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, A.M.; Barrow, B. The Table Tennis Triathlon: An Integrated Sport Education Season. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2016, 87, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwager, S. A Vehicle for Teaching Sportspersonship and Responsibility. JOPERD 2012, 83, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, G.; Hannon, J.C. An analysis of middle school students physical education physical activity preferences. Phys. Educ. 2008, 65, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kudlacek, M.; Fromel, K.; Groffik, D. Associations between adolescents’ preference for fitness activities and achieving the recommended weekly level of physical activity. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2020, 18, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vute, R.; Goltnik, A. Analysis of sport preferences among 13–21 year old youth with physical disabilities in Slovenia. Acta Univ. Palacki. Olomuc. Gymnica 2009, 39, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Green, K.; Thurston, M. ‘Activity choice’ and physical education in England and Wales. Sport Educ. Soc. 2009, 14, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, E.; Kussin, U.; Brandl-Bredenbeck, H.P. Der Sportunterricht Aus Schülerperspektive; DSB, Ed.; Meyer & Meyer: Aachen, Germany, 2006; pp. 115–152. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, R.; Pradas, F.; Castellar, C.; Díaz, A. Análisis de la situación del tenis de mesa como contenido de educación física en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. J. Sport Health Res. 2016, 8, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, R.; Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Rapún, M.; Peñarrubia, C.; Castellar, C. Análisis de la situación de los deportes de raqueta y pala en educación física en la etapa de educación secundaria en Murcia. Rev. Española De Educ. Física Y Deportes 2018, 420, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, D. Diagnostics to the level of sports and technical skills, knowledge and sports interests of the students. Act. Phys. Educ. Sport 2014, 4, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Wen, X.; Fu, Y.; Lee, J.E.; Zeng, N. Motor Skill Competence Matters in Promoting Physical Activity and Health. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9786368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.Z.; Hipscher, M.; Leung, R.W. Attitudes of High School Students toward Physical Education and Their Sport Activity Preferences. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, G. Children animation resources in the infant school and the primary school. Act. Phys. Educ. Sport 2014, 4, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.P. The Development Status quo and Countermeasure Research of the Table Tennis Elective in Shanghai General Colleges. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Langille, J.L.D.; Rodgers, W.M. Exploring the Influence of a Social Ecological Model on School-Based Physical Activity. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhr, K. Table tennis in secondary schools. Br. J. Phys. Educ. 1997, 28, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dollman, J. Social and Environmental Influences on Physical Activity Behaviours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonko, A.; Zanevskyy, I.; Bodnarchuk, O.; Andres, A.; Petryna, R.; Lapychak, I. Attitude of law college students towards physical culture and sports. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 780–785. [Google Scholar]

- Brug, J.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Loyen, A.; Ahrens, W.; Allais, O.; Andersen, L.F.; Cardon, G.; Capranica, L.; Chastin, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; et al. Determinants of diet and physical activity (DEDIPAC): A summary of findings. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Quintas, A.; Gallego-Tobón, C.; Castellar, C. A novel physical education teaching activity of racquet sports: Vince pong. J. Sport Health Res. 2017, 9, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, V.G.; Isaacs Larry, D. Human Motor Development, 9th ed.; Holcomb Hathaway: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2016; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steadward, R.D.; Wheeler, G.D.; Watkinson, E.J. Adapted Physical Activity; The university of Alberta Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.D.; Tsai, H.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Wuang, Y.P. The effectiveness of racket-sport intervention on visual perception and executive functions in children with mild intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, S.; Hastie, P.; van der Mars, H. Complete Guide to Sport Education, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Population | Primary school healthy students | Other educational stages (Secondary, adults, etc.) and students with any medical condition or disability |

| 2 | Study Design | Descriptive, intervention studying exclusively tennis table | Studies analyzing other racket sports |

| 3 | Outcomes | Academic variables related to the content of tennis table | Variables not directly related to the learning process |

| 4 | Others | English or Spanish language | Other languages |

| Author and Year | Study Population | Objective | Study Design | Intervention | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt (1987) [39] | N = UN * S = UN * A = UN * TP = Physical educator teachers C = New Zealand | The aim of the study is to demonstrate that the new TT system, based on a circular table, offers special advantages and motivation for its practice. The study presents the main characteristics of the game and its implications on sociological, psychological, philosophical, and cultural aspects. | DEX | Design a round TT for youth with basic rules of play that solve the problems of conventional play. | It increases the number of players simultaneously. The nets are arranged radially and can be adjusted to any point on the perimeter of the table, modifying the size of the playing areas depending on the skill level of the players. It can be practiced with a single ball or several simultaneously. This game has many organizational and psychological advantages, as well as a multitude of tactical and gameplay possibilities. | Round TT allows physical activity to be promoted by coexisting with technology, so it is quite recommendable for children and young people today. It represents a new valid form of sports and recreational practice, so authors recommend its introduction in educational centers worldwide. |

| Greenwood et al. (2001) [36] | N = 751 S = Boys and girls A = Middle school TP = Students C = United States | The study aimed to determine the physical activity preferences of boys and girls. | DST | Complete an “Activity Interest Inventory” over a two-day period during the spring semester. | Total activity preferences: TT 243 (32.4%) strong interest; 271 (36.1%) undecided; 237 (31.6%) little interest. Male activity preferences: TT 131 (33.8%) strong interest; 145 (37.4%) undecided; 112 (28.9%) little interest. Female activity preferences: TT 112 (30.9%) strong interest; 126 (34.7%) undecided; 125 (34.4%) little interest. | Students differ and coincide with their interests in the selection of specific sports activities. It would seem reasonable to allow students to have a say in the inclusion of sports activities in the PE curriculum. The PE teacher should be cautious in selecting activities that can be taught within the specific constraints of the school setting (facilities, space). |

| Schwager et al. (2012) [42] | N = UN * S = UN * A = Students in grades four and up TP = Physical educator teachers C = UN * | The study describes a game that can be played anywhere (classroom or cafeteria) and that allows students to understand the importance of practicing fair and responsible play. | DEX | The rules of the game of TT (serving, rallying, and scoring) are described, along with strategies and tactics with the idea of promoting responsibility and sportsmanship, through the inclusion of differentiated roles, responsibilities of the players, and multiple ways to achieve the success of the team. Each team selects a captain, a coach, and a statistician by signing a contract in which they agree to respect fair play and contribute to the team’s success. | Table top tennis is a game similar to TT, playable in a classroom or dining room with minimal equipment. It incorporates affordable skills for all students. The necessary materials are tables or desks, foam balls, and rope or adhesive tape. The goal is to hit the ball over the net onto the table so that the opponent cannot return it. The key question is: “What do you hit the ball with if you don’t use a racket?” Students can use the palm (right) or back (back) of either hand. Depending on the number of students and the number or size of tables, it can be played in teams, singles, or doubles. | PE teachers must overcome challenges to meet educational standards that classroom teachers do not experience. If there is no gym available, TT (with an educational format) is an activity that can be taught in the classroom or in another adapted location. It offers opportunities for students from fourth grade onwards to work on achieving some of the affective goals related to sportsmanship and personal responsibility. |

| Healy (2013) [40] | N = UN * S = UN * A = Infancy TP = Physical educator teachers C = UN * | The aim of this intervention is to provide likely measures to adapt TT to the PE context. | DEX | Adapt task constraints by adapting the materials used, especially for children with disabilities, to help them acquire fundamental motor skills. | TT is an activity that involves hitting. Your game can be adapted by tying a balloon to the net with a string that reaches the edge of the table. This new situation adapts the speed and size, making it easier to play. It also allows you to play it on the floor or on a table, allowing the child to kneel, sit, or stand. | By using adapted equipment (e.g., TT with a balloon), children can learn, practice, and develop their motor skills to the fullest. These material adaptations allow for the development of inclusive PE and the preparation of physical educators to work with students with disabilities. |

| Buchanan & Barrow (2016) [41] | N = UN * S = UN * A = Primary school TP = Physical educator teachers C = United States | To describe the integration of three learning domains: cognitive (English language [ELA]—grammar and vocabulary), affective (social responsibility), and psychomotor skills (TT using the pedagogical model of sports education). | DEX | The TT triathlon is a team competition where you work by roles. Students establish who will play each role. Students work together to create a name for the team. Each team will learn and compete in table tennis to earn points. Each encounter will consist of a TT match, a vocabulary and grammar challenge, and an online challenge in freerice.com. To win the match, the teams work to succeed in all aspects: TT, ELA, and social responsibility. | PE—Psychomotor Mastery. It is a game that can be implemented inexpensively by buying only rackets, balls, and nets. English Language and Literature—Cognitive Mastery. The conventions of standard English and the acquisition and use of vocabulary were chosen as appropriate for integration into the sports education unit. Social Responsibility—Affective Domain. The pedagogical model of sports education focuses on social responsibility, since students must work as a team and each one must responsibly play their specific roles. Social responsibility is being promoted both locally and globally. | Students and teachers benefit from the integration of content areas by showing how PE content integrates seamlessly with other knowledge areas, improving children’s overall learning. At the school level, content integration is a way to participate in a collaborative teaching model. Incorporating social responsibility helps young people focus on the needs of others, whether at the team level or on a global level. An integrated, well-implemented curriculum benefits everyone, but especially students. |

| Hoffmann et al. (2018) [37] | N = 498 S = 97 male and 401 females A = 44.58 ± 10.56 years Primary school TP = Physical educator teachers C = Germany | To investigate the parameters that influence the decision to teach specific sports, in particular RS, in primary PE. It is hypothesized that (1) racquet sports are taught in PE classes, and (2) specific parameters (e.g., work experience, gender, and teacher qualifications) influence the decision to teach racquet sports as educational content. | DST | A standardized questionnaire was designed and subdivided into five sections: general information about participation, the educational center, the faculty, the framework (location and materials), and PE (e.g., guidelines and personal preferences for the implementation of racquet sports). Different types of questions are included (single-choice, multiple-choice, and open-ended). | The teachers’ responses indicate that 72.89% (363) of the schools have internal curricula. Within these curricula, 67.97% (244) include RS. A total of 69.88% (348) of the teachers teach RS classes in primary PE, divided into different types: basic games (59.77%), badminton (54.6%), TT (20.59%), and tennis (14.66%). | Two out of three primary school teachers teach RS in their PE classes, particularly basic games and badminton. Gender had no impact on the decision to teach RS, The study identified four specific parameters that influence the implementation of the teaching of RS in primary schools: the school’s internal PE curriculum; work experience; being a specialist in PE; and personal affinity for practicing RS during free time. It is suggested that a change in study regulations, for example, by offering extra-occupational courses to teachers, may benefit the implementation of RS in primary schools. |

| Xiao et al. (2020) [38] | N = 1526 Primary students: 755 (49.48%) Secondary students: 771 (50.52%) S = UN * A = 9 to 16 years (12.31 ± 1.32 years) TP = Physical educator teachers C = China | To explore the factors affecting adolescent TT skills (ATTS) in Shanghai from a socio-ecological perspective, including individual factors, social support, and physical environment. The following hypotheses were raised: (1) individual factors (motivation, self-efficacy), social support (support from parents, friends, PE teacher), and physical environment (school and community) have an impact on the performance of the ATTS test; (2) among levels of social ecology, different levels have different degrees of impact on ATTS improvement; and (3) in addition to the direct effect, the influence of individual factors on ATTS test performance has a mediating effect. | DST | Participants completed a questionnaire based on social ecological theory after taking the ATTS test. | Individual factors played an important role in improving ATTS test scores; (2) social support was positively related to ATTS test score; and (3) physical environment was also significantly associated with ATTS test score. The results of the multiple linear regression and SEM analysis showed that, among the three levels, individual factors were the most important for the improvement of ATTS. Self-efficacy was identified as an important factor related to ATTS test score. | The factor that most influences ATTS is individual factors, followed by social support, and the one that influences the least is the physical environment. Therefore, fostering intrinsic interest is critical to facilitating teens’ continued activity. Second, friends should support each other, and parents should properly encourage teens regarding the practice of TT. Schools should provide more facilities for playing TT. PE teachers should respect the ideas of teenagers, listen to their opinions, and encourage them to participate in TT training. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortega-Zayas, M.A.; Cardona-Linares, A.J.; Lecina, M.; Ochiana, N.; García-Giménez, A.; Pradas, F. Table Tennis as a Tool for Physical Education and Health Promotion in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review. Sports 2025, 13, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080251

Ortega-Zayas MA, Cardona-Linares AJ, Lecina M, Ochiana N, García-Giménez A, Pradas F. Table Tennis as a Tool for Physical Education and Health Promotion in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review. Sports. 2025; 13(8):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080251

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtega-Zayas, M. A., A. J. Cardona-Linares, M. Lecina, N. Ochiana, A. García-Giménez, and F. Pradas. 2025. "Table Tennis as a Tool for Physical Education and Health Promotion in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review" Sports 13, no. 8: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080251

APA StyleOrtega-Zayas, M. A., Cardona-Linares, A. J., Lecina, M., Ochiana, N., García-Giménez, A., & Pradas, F. (2025). Table Tennis as a Tool for Physical Education and Health Promotion in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review. Sports, 13(8), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080251