Exercise-Induced Biomarker Modulation in Sarcopenia: From Inflamm-Aging to Muscle Regeneration

Abstract

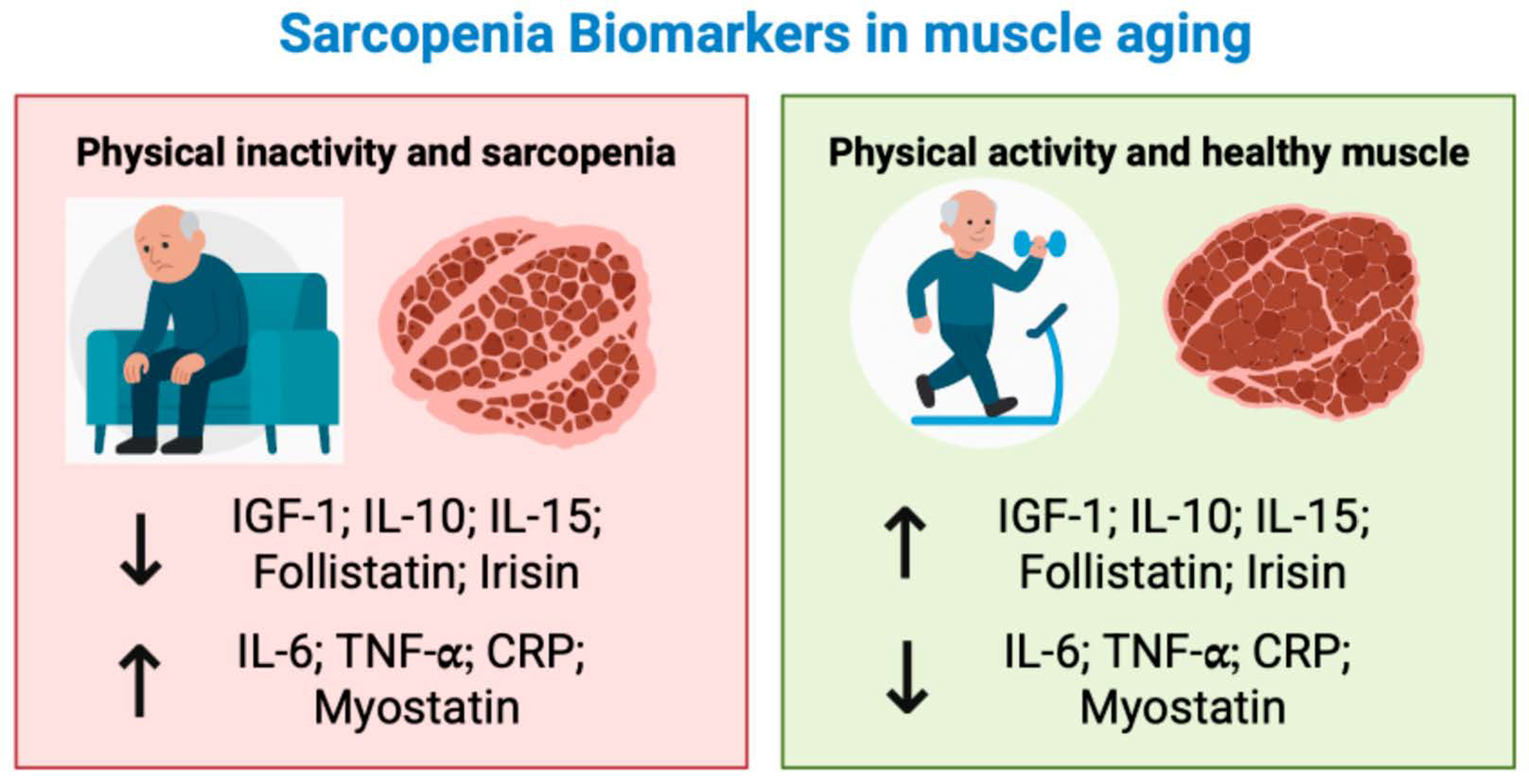

1. Sarcopenia: From Pathophysiology to Biomarkers and Exercise Modulation

2. The Effects of Exercise on Biomarkers Related to Sarcopenia: Where We Are

3. Hormones

4. Pro-Inflammatory Biomarkers: Interleukin-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and C-Reactive Protein

5. Anti-Inflammatory Biomarkers: Interleukin-10 and Interleukin-15

6. Myostatin and Follistatin

7. Irisin

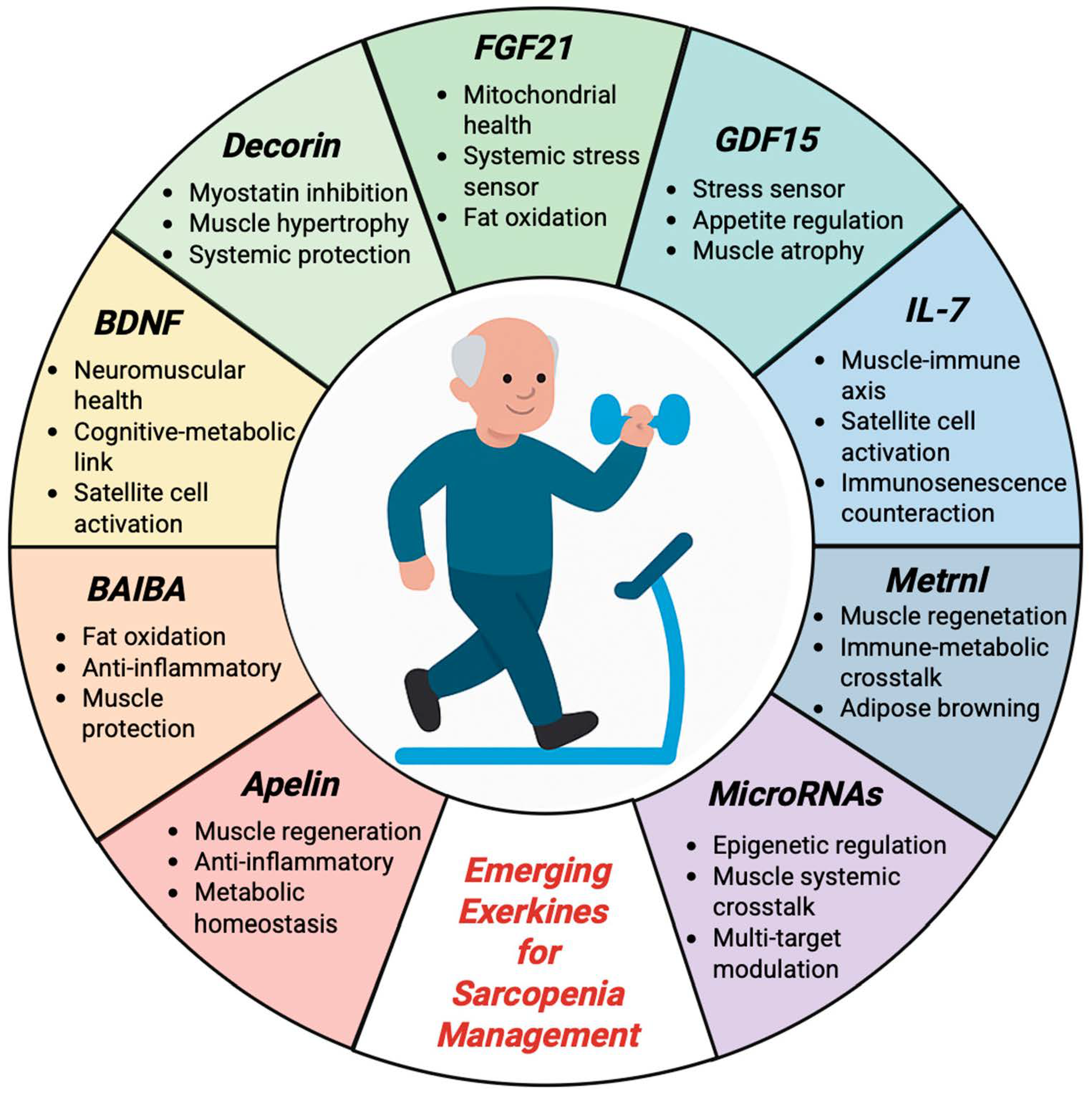

8. Emerging Biomarkers and Molecular Perspectives

8.1. Apelin

8.2. Beta-Aminoisobutyric Acid

8.3. Brain-Derived Neutrophic Factor

8.4. Decorin

8.5. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21

8.6. Growth Differentiation Factor 15

8.7. Interleukin 7

8.8. Meteorin-like Factor

8.9. MicroRNAs

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1 RM | One Repetition Maximum |

| 6MWT | Six-Minute Walk Test |

| ALMI | Appendicular Lean Mass Index |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ASMMI | Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index |

| BAIBA | Beta-Aminoisobutyric Acid |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CON | Control Group |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DEXA | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| EX | Exercise |

| EX + CON | Exercise + Control Group |

| EX + PRO | Exercise + Protein Supplement Group |

| FFM | Fat-Free Mass |

| FM | Fat Mass |

| FNDC5 | Fibronectin Type III Domain-Containing Protein 5 |

| FoxO | Forkhead Box O |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 |

| GDF15 | Growth Differentiation Factor 15 |

| GDF-8 | Growth Differentiation Factor 8 (Myostatin) |

| GLUT4 | Glucose Transporter Type 4 |

| GFRAL | Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Family Receptor Alpha-Like |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MGF | Mechanical Growth Factor |

| Metrnl | Meteorin-Like Protein |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| MuRF1 | Muscle RING Finger 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| PL | Placebo |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PRO | Protein Supplement Group |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

| RT | Resistance Training |

| RT + EP | Resistance Training + Epicatechin |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SSPB | Short Physical Performance Battery |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| THR | Target Heart Rate |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go Test |

References

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Dani, M.; Kemp, P.; Fertleman, M. Acute Sarcopenia after Elective and Emergency Surgery. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.A.; Bonato, M.; La Torre, A.; Banfi, G. The Role of the Molecular Clock in Promoting Skeletal Muscle Growth and Protecting against Sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019, 393, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Zaaria, M.; Pasleau, F.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Health Outcomes of Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Calvani, R.; Cesari, M.; Tosato, M.; Martone, A.M.; Ortolani, E.; Savera, G.; Salini, S.; Sisto, A.; Picca, A.; et al. Sarcopenia: An Overview on Current Definitions, Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthon, P.M.; Visser, M.; Arai, H.; Ávila-Funes, J.A.; Barazzoni, R.; Bhasin, S.; Binder, E.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Chen, L.K.; et al. Defining terms commonly used in sarcopenia research: A glossary proposed by the Global Leadership in Sarcopenia (GLIS) Steering Committee. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papadimitriou, K.; Voulgaridou, G.; Georgaki, E.; Tsotidou, E.; Zantidou, O.; Papandreou, D. Exercise and Nutrition Impact on Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia—The Incidence of Osteosarcopenia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Balntzi, V.; Gray, S.R.; Lara, J.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, J.; Geerlings, M.A.J.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Phassouliotis, C.; Lim, W.K.; Maier, A.B. Prevalence of sarcopenia as a comorbid disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 131, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, P.M.; Musci, R.V.; Hinkley, J.M.; Miller, B.F. Mitochondria as a Target for Mitigating Sarcopenia. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethgen, O.; Beaudart, C.; Buckinx, F.; Bruyère, O.; Reginster, J.Y. The Future Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Europe: A Claim for Public Health Action. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2017, 100, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Domingos, C.; Monteiro, D.; Morouço, P. A Review on Aging, Sarcopenia, Falls, and Resistance Training in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournadre, A.; Vial, G.; Capel, F.; Soubrier, M.; Boirie, Y. Sarcopenia. Jt. Bone Spine 2019, 86, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonewald, L. Use it or lose it to age: A review of bone and muscle communication. Bone 2019, 120, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannataro, R.; Cione, E.; Bonilla, D.A.; Cerullo, G.; Angelini, F.; D’Antona, G. Strength training in elderly: An useful tool against sarcopenia. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 950949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, R.; Choi, H.; Lee, S.J.; Bae, G.U. Understanding of sarcopenia: From definition to therapeutic strategies. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2021, 44, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.D.; Chen, H.C.; Huang, S.W.; Liou, T.H. The Role of Muscle Mass Gain Following Protein Supplementation Plus Exercise Therapy in Older Adults with Sarcopenia and Frailty Risks: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, S.K. Sarcopenia: A Contemporary Health Problem among Older Adult Populations. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, K.; Fuentes, J.; Márquez, J.L. Physical Inactivity, Sedentary Behavior and Chronic Diseases. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2017, 38, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B.; Feehan, J.; Lombardi, G.; Duque, G. Muscle, Bone, and Fat Crosstalk: The Biological Role of Myokines, Osteokines, and Adipokines. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020, 18, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Picca, A.; Marini, F.; Biancolillo, A.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Gervasoni, J.; Bossola, M.; Cesari, M.; Onder, G.; Landi, F.; et al. Inflammatory signatures in older persons with physical frailty and sarcopenia: The frailty “cytokinome” at its core. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 122, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatic, M.; von Haehling, S.; Ebner, N. Inflammatory biomarkers of frailty. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 133, 110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.G.; Markofski, M.M.; Carrillo, A.E. Elevated Inflammatory Status and Increased Risk of Chronic Disease in Chronological Aging: Inflamm-aging or Inflamm-inactivity? Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianoudis, J.; Bailey, C.A.; Daly, R.M. Associations between sedentary behaviour and body composition, muscle function and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.K.; Ferner, R.E. Biomarkers—A General Review. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2017, 76, 9.23.1–9.23.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Moon, K.M.; Min, K.W. Exercise-Induced Myokines can Explain the Importance of Physical Activity in the Elderly: An Overview. Healthcare 2020, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.W.; Yu, K.; Shyh-Chang, N.; Li, G.X.; Jiang, L.J.; Yu, S.L.; Xu, L.Y.; Liu, R.J.; Guo, Z.J.; Xie, H.Y.; et al. Circulating factors associated with sarcopenia during ageing and after intensive lifestyle intervention. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.S.; Gerszten, R.E.; Taylor, J.M.; Pedersen, B.K.; van Praag, H.; Trappe, S.; Febbraio, M.A.; Galis, Z.S.; Gao, Y.; Haus, J.M.; et al. Exerkines in health, resilience and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, L.; Bondi, D.; Pini, N.; Marramiero, L.; Di Filippo, E.S. The wonder exerkines—Novel insights: A critical state-of-the-art review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, G.; Calcaterra, G.; Casciani, F.; Pecorelli, S.; Mehta, J.L. ‘Exerkines’: A Comprehensive Term for the Factors Produced in Response to Exercise. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, G.; Phillips, S.M. An elusive consensus definition of sarcopenia impedes research and clinical treatment: A narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 86, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International Exercise Recommendations in Older Adults (ICFSR): Expert Consensus Guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayomzadeh, M.; Hackett, D.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Gholami, M.; Hosseini Rouzbahani, N.; Azevedo Voltarelli, F. Combined training improves the diagnostic measures of sarcopenia and decreases the inflammation in HIV-infected individuals. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayomzadeh, M.; Hackett, D.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Gholami, M.; Rouzbahani, N.H.; Voltarelli, F.A. Effects of resistance exercise and whey protein supplementation on skeletal muscle strength, mass, physical function, and hormonal and inflammatory biomarkers in healthy active older men: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 158, 111651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, A.B.; Cesari, M.; Corrêa, H.L.; Neves, R.V.P.; Sousa, C.V.; Deus, L.A.; Souza, M.K.; Reis, A.L.; Moraes, M.R.; Prestes, J.; et al. Effects of pre-dialysis resistance training on sarcopenia, inflammatory profile, and anemia biomarkers in older community-dwelling patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, F.; Biglari, S.; Afousi, A.G.; Gaeini, A.A. Improvement in Skeletal Muscle Strength and Plasma Levels of Follistatin and Myostatin Induced by an 8-Week Resistance Training and Epicatechin Supplementation in Sarcopenic Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urzi, F.; Marusic, U.; Ličen, S.; Buzan, E. Effects of Elastic Resistance Training on Functional Performance and Myokines in Older Women—A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 830–834.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Liang, J.; Kirberger, M.; Chen, N. Irisin, an exercise-induced bioactive peptide beneficial for health promotion during aging process. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 80, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Khanabdali, R.; Kalionis, B.; Wu, J.; Wan, W.; Tai, X. An Update on Inflamm-Aging: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 8426874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Flato, U.A.P.; Tofano, R.J.; Goulart, R.A.; Guiguer, E.L.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Buchaim, D.V.; Araújo, A.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Reina, F.T.R.; et al. Physical Exercise and Myokines: Relationships with Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Neto, E.V.P.; Goulart, R.D.A.; Bechara, M.D.; Chagas, E.F.B.; Audi, M.; Campos, L.M.G.; Guiger, E.L.; Buchaim, R.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; et al. Myokines: A descriptive review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilski, J.; Pierzchalski, P.; Szczepanik, M.; Bonior, J.; Zoladz, J.A. Multifactorial Mechanism of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity. Role of Physical Exercise, Microbiota and Myokines. Cells 2022, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlavani, H.A. Exercise Therapy for People With Sarcopenic Obesity: Myokines and Adipokines as Effective Actors. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 811751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, A.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Association between sarcopenia and levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 in the elderly. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, A.A.; Feehan, J.; Phu, S.; Duque, G. Current and emerging biomarkers of frailty in the elderly. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, H.; Smith, K.; Atherton, P.J.; Idris, I. Role of insulin in the regulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis and breakdown: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.R.; Long, J.Z.; White, J.P.; Svensson, K.J.; Lou, J.; Lokurkar, I.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Ruas, J.L.; Wrann, C.D.; Lo, J.C.; et al. Meteorin-like is a hormone that regulates immune-adipose interactions to increase beige fat thermogenesis. Cell 2014, 157, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jun, H.S. Role of Myokines in Regulating Skeletal Muscle Mass and Function. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xie, W.; Fu, X.; Lu, W.; Jin, H.; Lai, J.; Zhang, A.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W. Inflammation and sarcopenia: A focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 154, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunner, B.E.M.; Wachsmuth, N.B.; Eckstein, M.L.; Scherl, L.; Schierbauer, J.R.; Haupt, S.; Stumpf, C.; Reusch, L.; Moser, O. Myokines and Resistance Training: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Li, B.; Sun, A.; Guo, F. Interleukin-10 Family Cytokines Immunobiology and Structure. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1172, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, D.; Skrzypczak-Zielińska, M.; Ratajczak, A.E.; Szymczak-Tomczak, A.; Eder, P.; Słomski, R.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Myostatin and Follistatin—New Kids on the Block in the Diagnosis of Sarcopenia in IBD and Possible Therapeutic Implications. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chiu, Y.L.; Kao, T.W.; Peng, T.C.; Yang, H.F.; Chen, W.L. Cross-sectional associations among P3NP, HtrA, Hsp70, Apelin and sarcopenia in Taiwanese population. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariati, I.; Bonanni, R.; Onorato, F.; Mastrogregori, A.; Rossi, D.; Iundusi, R.; Gasbarra, E.; Tancredi, V.; Tarantino, U. Role of Physical Activity in Bone-Muscle Crosstalk: Biological Aspects and Clinical Implications. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; He, W.; Hou, J.; Chen, K.; Huang, M.; Yang, M.; Luo, X.; Li, C. Bone and Muscle Crosstalk in Aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 585644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaianni, G.; Storlino, G.; Sanesi, L.; Colucci, S.; Grano, M. Myokines and Osteokines in the Pathogenesis of Muscle and Bone Diseases. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020, 18, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, D.A.; Jang, I.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Yi, H.S.; Lee, E.; et al. Association between serum FGF21 level and sarcopenia in older adults. Bone 2021, 145, 115877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, K.; Kleinert, M.; Klaus, S. The Role of GDF15 as a Myomitokine. Cells 2021, 10, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, M.; Clemmensen, C.; Sjøberg, K.A.; Carl, C.S.; Jeppesen, J.F.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P.; Kiens, B.; Richter, E.A. Exercise increases circulating GDF15 in humans. Mol. Metab. 2018, 9, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, R.; Durum, S.K. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: Intelligent design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baht, G.S.; Bareja, A.; Lee, D.E.; Rao, R.R.; Huang, R.; Huebner, J.L.; Bartlett, D.B.; Hart, C.R.; Gibson, J.R.; Lanza, I.R.; et al. Meteorin-like facilitates skeletal muscle repair through a Stat3/IGF-1 mechanism. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Lee, K.P.; Kwon, K.S.; Suh, Y. MicroRNAs in Skeletal Muscle Aging: Current Issues and Perspectives. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.; Greco, F.; Quinzi, F.; Scionti, F.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Mancini, A.; Buono, P.; Emerenziani, G.P. The Effect of Physical Activity/Exercise on miRNA Expression and Function in Non-Communicable Diseases—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proia, P.; Rossi, C.; Alioto, A.; Amato, A.; Polizzotto, C.; Pagliaro, A.; Kuliś, S.; Baldassano, S. MiRNAs Expression Modulates Osteogenesis in Response to Exercise and Nutrition. Genes 2023, 14, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Participants | Age Mean ± SD | Intervention | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop-Out | Sarcopenia | Biomarkers | ||||

| Ghayomzadeh et al. [34] | 40 subjects with HIV infection (20 men and 20 women) randomized in: combined training (n = 20; men = 10, women = 10), no exercise (n = 20; men = 10, women = 10) | 38 ± 7 | Duration: 6 months Frequency: 3 session/week Exercise Combined: -Endurance: 20 min on treadmill at 65–80% of THR -Resistance: 3 × 4–20 at 50/85% | 3 subjects (2 in combined training and 1 in no exercise) | Combined training: ↑ ALMI a,b, ↑ Handgrip test a,b, ↑ TUG a,b, ↓ FM a, ↑ FFM a,b No exercise: ↓ ALMI b, ↓ Handgrip test b, ↓ TUG b ↑ FM b, ↓ FFM b | Combined training: ↓ IL-6 a,b, ↓ TNF-α a,b, ↑ IGF-1 a,b, ↓ myostatin a,b No exercise: ↑ IL-6 a,b, ↑ TNF-α a,b, ↑ IGF-1 b, ↓ myostatin b |

| Griffen et al. [35] | 39 subjects randomized in: control (CON; n = 10), whey protein (PRO; n = 10), resistance exercise (EX + CON; n = 10), resistance exercise + whey protein (EX + PRO; n = 9) | 67 ± 1 | Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: 2 session/week Exercise: 3 × 10–12 from 60% to 80% of 1 RM | 3 subjects (1 in CON, 1 in PRO, 1 in EX + CON) | CON: No changes PRO: ↑ 4 m gait speed EX + CON: ↑ leg extension a,b, ↑ leg press a,b EX + PRO: ↑ leg extension a,b, ↑ leg press a,b, ↓ Waist circumference b CON + PRO: ↑ FM b, ↑ BMI b EX + CON + EX + PRO: ↑ FFM b, ↓ FM a, ↑ 6MWT a | CON: No changes PRO: No changes EX + CON: ↓ insulin a, ↓ IL-6, ↓ TNF-α EX + PRO: ↓ IL-6 a, ↓ TNF-α a, ↑ salivary cortisol PRO + EX + PRO: ↑ salivary cortisol a, ↑ myostatin a |

| Gadelha et al. [36] | 137 subjects with chronic kidney disease randomized in: Resistance Training (n = 72) and Control (n = 67) | 64 ± 4 | Duration: 24 weeks Frequency: 3 session/week Exercise: bodyweight, e-Lastic cable, Bumbbells, Weighted cuffs | 32 subjects (17 in control and 15 in resistance training) | Resistance Training: ↓ Waist Circunference c, ↓ FM c, ↑ Handgrip Strength c, ↓ TUG c, ↑ 6MWT c, Control: No Changes | Resistance Training: ↓ IL-6, ↓ TNF-α c, ↑ IL-10 Control: No Changes |

| Mafi et al. [37] | 68 elderly males randomized in: Resistance Training (RT, n = 17), Resistance Training + Epicatechin (RT + EP, n = 17), Epicatechin (EP, n = 17), Placebo (PL, n = 17) | 69 ± 3 | Duration: 8 weeks Frequency: 3 session/week Exercise: 45 min of resistance exercise [3 × 8–12 (60–80% 1 RM)] | 6 subjects (3 in RT, 2 in RT + EP, 1 in PL) | Resistance Training: ↑ BMI, ↑ ASMMI, ↑ leg press, ↑ chest press, ↑ TUG Resistance Training + Epicatechin: ↑ BMI, ↑ ASMMI, ↑ leg press, ↑ chest press, ↑ TUG Epicatechin: ↑ ASMMI, ↑ TUG, Placebo: No changes | Resistance Training: ↓ Myostatin, ↑ Follistatin Resistance Training + Epicatechin: ↓ Myostatin, ↑ Follistatin Epicatechin: ↑ Follistatin Placebo: No changes |

| Urzi et al. [38] | 35 female nursing home residents randomized in: training group (n = 18) and control group (n = 17) | 84 ± 8 | Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: 3 session/week Exercise: 40 min of progressive elastic resistance training program | 15 subjects (7 in training group and 8 in control group) | Training Group: ↑ SSPB a, ↑ Gait Speed a, ↑ Chair rise d Control Group: No changes | Training Group: ↑ IL-15, ↑ BDNF a Control Group: No changes |

| Zhang et al. [39] | 60 older adults with sarcopenia randomized in: multicomponent exercise group (n = 30) and control group (n = 30) | 72 ± 6 | Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: 3 session/week Exercise: multicomponent training including resistance, balance, mobility, and walking (60 min/session) | 4 subjects (2 in exercise group and 2 in control group | Exercise group: ↑ ASMMI a,b, ↑ Handgrip strength a,b, ↑ SPPB a,b, ↓ TUG a,b Control group: No changes | Exercise group: ↑ Irisin a,b Control group: No changes |

| Reference | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | Quality Score | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghayomzadeh et al. [34] | 9/10 | Excellent | ||||||||||

| Griffen et al. [35] | 9/10 | Excellent | ||||||||||

| Gadelha et al. [36] | 9/10 | Excellent | ||||||||||

| Mafi et al. [37] | 7/10 | Good | ||||||||||

| Urzi et al. [38] | 7/10 | Good | ||||||||||

| Zhang et al. [39] | 9/10 | Excellent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marmondi, F.; Ferrando, V.; Filipas, L.; Codella, R.; Ruggeri, P.; La Torre, A.; Faelli, E.L.; Bonato, M. Exercise-Induced Biomarker Modulation in Sarcopenia: From Inflamm-Aging to Muscle Regeneration. Sports 2025, 13, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120444

Marmondi F, Ferrando V, Filipas L, Codella R, Ruggeri P, La Torre A, Faelli EL, Bonato M. Exercise-Induced Biomarker Modulation in Sarcopenia: From Inflamm-Aging to Muscle Regeneration. Sports. 2025; 13(12):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120444

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarmondi, Federica, Vittoria Ferrando, Luca Filipas, Roberto Codella, Piero Ruggeri, Antonio La Torre, Emanuela Luisa Faelli, and Matteo Bonato. 2025. "Exercise-Induced Biomarker Modulation in Sarcopenia: From Inflamm-Aging to Muscle Regeneration" Sports 13, no. 12: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120444

APA StyleMarmondi, F., Ferrando, V., Filipas, L., Codella, R., Ruggeri, P., La Torre, A., Faelli, E. L., & Bonato, M. (2025). Exercise-Induced Biomarker Modulation in Sarcopenia: From Inflamm-Aging to Muscle Regeneration. Sports, 13(12), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120444