The Effect of Acute Exercise on State Anxiety: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

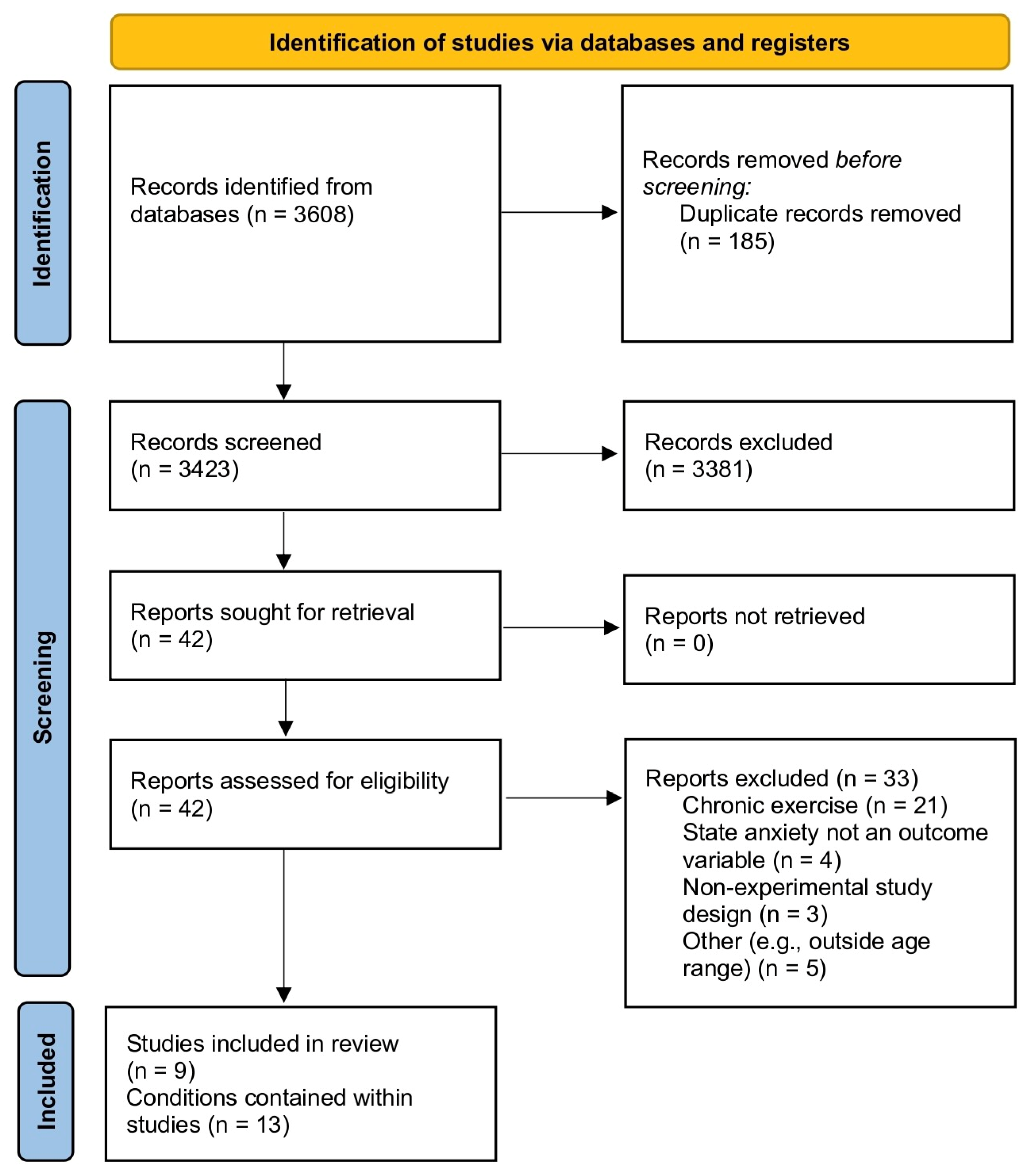

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Role of Modality

3.4. Role of Intensity

3.5. Role of Duration

3.6. Evaluation of Study Quality

3.7. Control Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Intensity | |||

| Moderate | Vigorous | Not quantified | |

| Effective > control | 2 | 3 | - |

| Effective = to control | 1 | 1 | - |

| Ineffective | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Modality | |||

| Cycle ergometer | Treadmill | Exergame | |

| Effective > control | 4 | 1 | - |

| Effective = to control | 1 | - | 1 |

| Ineffective | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Duration | |||

| <30 min | 30 min | >30 min | |

| Effective > control | 2 | - | 2 |

| Effective = to control | - | 1 | 2 |

| Ineffective | 2 | 3 | - |

| Total | 4 | 4 | 4 |

References

- Every-Palmer, S.; Jenkins, M.; Gendall, P.; Hoek, J.; Beaglehole, B.; Bell, C.; Williman, J.; Rapsey, C.; Stanley, J. Psychological distress, anxiety, family violence, suicidality, and wellbeing in New Zealand during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Survey Data Explorer 2022. Available online: https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2021-22-annual-data-explorer/_w_cf3d98e9/#!/home (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Barlow, D.H. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.-P.; Burstein, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Avenevoli, S.; Cui, L.; Benjet, C.; Georgiades, K.; Swendsen, J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pine, D.S.; Cohen, P.; Gurley, D.; Brook, J.; Ma, Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998, 55, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Yamamoto, S.S.; Brosschot, J.F. The Relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 141, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Stubbs, B.; Meyer, J.; Heissel, A.; Zech, P.; Vancampfort, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Deenik, J.; Firth, J.; Ward, P.B. Physical activity protects from incident anxiety: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Landers, D.M.; Hatfield, B.D.; Kubitz, K.A.; Salazar, W. A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise. Sports Med. 1991, 11, 143–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensari, I.; Greenlee, T.A.; Motl, R.W.; Petruzzello, S.J. Meta-analysis of acute exercise effects on state anxiety: An update of randomized controlled trials over the past 25 years. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the pedro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focht, B.C. Pre-exercise anxiety and the anxiolytic responses to acute bouts of self-selected and prescribed intensity resistance exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2002, 42, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kandola, A.; Vancampfort, D.; Herring, M.; Rebar, A.; Hallgren, M.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B. Moving to beat anxiety: Epidemiology and therapeutic issues with physical activity for anxiety. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.; Jallo, N.; Rodgers, B.; Kinser, P.; Dautovich, N. Anxiety in menopause: A distinctly different syndrome? J. Nurse Pract. 2019, 15, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, L.T.; Rhodes, D.J.; Gostout, B.S.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A. Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences. Maturitas 2010, 65, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and anovas. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lago, T.R.; Hsiung, A.; Leitner, B.P.; Duckworth, C.J.; Chen, K.Y.; Ernst, M.; Grillon, C. Exercise decreases defensive responses to unpredictable, but not predictable, threat. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, E.; Vos, M.; Keller, V.; Koch, S.; Takano, K.; Cludius, B. the benefits of physical exercise on state anxiety: Exploring possible mechanisms. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2022, 23, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebouthillier, D.M.; Asmundson, G.J. A single bout of aerobic exercise reduces anxiety sensitivity but not intolerance of uncertainty or distress tolerance: A randomized controlled Trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.E.; Asmundson, G.J. A single bout of either sprint interval training or moderate intensity continuous training reduces anxiety sensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 14, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.L.; Tomporowski, P.D. Acute effects of exercise on attentional bias in low and high anxious young adults. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 12, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broman-Fulks, J.J.; Kelso, K.; Zawilinski, L. Effects of a single bout of aerobic exercise versus resistance training on cognitive vulnerabilities for anxiety disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, N.F.; Welch, A.S. Walking versus biofeedback: A comparison of acute interventions for stressed students. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, N.S.; Viana, R.B.; Silva, W.F.; Santos, D.A.; Costa, T.G.; Campos, M.H.; Vieira, C.A.; Vancini, R.L.; Andrade, M.S.; Gentil, P. Effect of both dance exergame and a traditional exercise on state anxiety and enjoyment in women. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2021, 62, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, V.; Viana, R.; Morais, N.; Costa, G.; Andrade, M.; Vancini, R.; De Lira, C. State anxiety after exergame beach volleyball did not differ between the single and multiplayer modes in adult men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R. State-Trait Anxiety (STAI) Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Cox, B.J.; Deacon, B.; Heimberg, R.G.; Ledley, D.R.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Holaway, R.M.; Sandin, B.; Stewart, S.H. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity index-3. Psychol. Assess. 2007, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, M.G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J.; Hingston, P.; Masek, M. Considerations for the design of exergames. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in Australia and Southeast Asia, Perth, Australia, 1–4 December 2007; pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, K.; Norton, L.; Sadgrove, D. Position statement on physical activity and exercise intensity terminology. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.-M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, T.R.; Hsiung, A.; Leitner, B.P.; Duckworth, C.J.; Balderston, N.L.; Chen, K.Y.; Grillon, C.; Ernst, M. Exercise modulates the interaction between cognition and anxiety in humans. Cogn. Emot. 2019, 33, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Shivakumar, G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P. The breathing conundrum—Interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; Mcdowell, C.P.; Lyons, M.; Herring, M.P. The effects of resistance exercise training on anxiety: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2521–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; Mcdowell, C.P.; Lyons, M.; Herring, M.P. Resistance exercise training for anxiety and worry symptoms among young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmundson, G.J.; Fetzner, M.G.; Deboer, L.B.; Powers, M.B.; Otto, M.W.; Smits, J.A. Let’s get physical: A contemporary review of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for anxiety and its disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabourin, B.C.; Stewart, S.H.; Watt, M.C.; Krigolson, O.E. Running as interoceptive exposure for decreasing anxiety sensitivity: Replication and extension. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broman-Fulks, J.J.; Berman, M.E.; Rabian, B.A.; Webster, M.J. Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1970, 2, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenko, Z.; Kahn, R.M.; Berman, C.J.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Jones, L. Do exercisers maximize their pleasure by default? using prompts to enhance the affective experience of exercise. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2020, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.; Parfitt, G. Exercise experience influences affective and motivational outcomes of prescribed and self-selected intensity exercise. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2012, 22, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapen, J.; Sommerijns, E.; Vancampfort, D.; Sienaert, P.; Pieters, G.; Haake, P.; Probst, M.; Peuskens, J. State anxiety and subjective well-being responses to acute bouts of aerobic exercise in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.A.; Parfitt, G. A quantitative analysis and qualitative explanation of the individual differences in affective responses to prescribed and self-selected exercise intensities. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.L.; Trivedi, M.H.; Kampert, J.B.; Clark, C.G.; Chambliss, H.O. Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The panas scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofrano-Prado, M.C.; Hill, J.O.; Silva, H.J.G.; Freitas, C.R.M.; Lopes-De-Souza, S.; Lins, T.A.; Do Prado, W.L. Acute effects of aerobic exercise on mood and hunger feelings in male obese adolescents: A crossover study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, M.; Steinlechner, M.; Ruedl, G.; Ledochowski, L.; Rumpold, G.; Taylor, A.H. Acute effects of brisk walking on affect and psychological well-being in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 95, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Date | n | Primary Intervention Time/Modality/Intensity | Control Condition(s) | Comparison Condition(s) | Measurement Scale & Mean (SD) Baseline Anxiety Score | Assessment Points | Main Result | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LeBouthillier and Asmundson, 2015 [18] | 41 | 20 min/spin bike sprint interval/vigorous intensity @ 60–80% age-adjusted heart rate reserve | Stretching | ASI-3 17.5 (13.0) Exercise 28.2 (12.8) Stretching | Pre, immediately post, 3-, and 7-days post | Anxiety significantly lower than control post-exercise, maintained across follow-up timepoints. | Exercise group: d = 0.70 (medium) | |

| Broman-Fulks, Kelso and Zawilinski, 2015 [21] | 77 | 20 min/treadmill/moderate @ 65–75 HRmax | Quiet rest | Time-matched resistance training to failure | STAI-S 30.3 (6.7) Aerobic 30.7 (6.3) Resistance 28.5 (7.4) Control | Pre, 5 min post | No conditions significantly reduced anxiety. | No change in any condition |

| Meier and Welch, 2016 [22] | 32 | 10 min/treadmill/self-paced intensity | Biofeedback breathing task OR Studying | STAI-T: 25.9 (8.5) PSS: 22.1 (4.3) | Pre, immediately post, and 15 min post | Anxiety significantly reduced post biofeedback condition; no change with other conditions. | Biofeedback condition: η2 = 0.27 (large) Interaction effect: η2 = 0.12 (large) | |

| Cooper and Tomporowski, 2017 [20] | 64 | 25 min/cycle ergometry/moderate intensity @ 45% V̇O2 reserve | Quiet rest | STAI-T 38.5 (10.1) Exercising 40.6 (14.1) Control | Pre, 5, and 20 min post | Anxiety was significantly lower following exercise for the high-trait anxious group only. | High STAI-T: η2p = 0.09 (medium) | |

| Lago et al., 2018 [16] | 17 | 30 min/cycle ergometry/vigorous @ 60–70% heart rate reserve | Cycling @ 10–20%HRR | STAI-S Values not given | Pre, immediately post | Neither exercise condition significantly reduced anxiety | Insufficient data | |

| Mason and Asmundson, 2018 [19] | 63 | 45 min/cycle ergometry/moderate intensity @ 70% age-predicted HRmax | Waitlist | Sprint intervals/vigorous @ 85%HRmax | ASI-3 19.6 (14.6) WL 20.8 (15.7) MICT 22.4 (15.9) SIT | Pre, post, 3-, and 7-days post | Significant reductions with both exercise conditions compared to control group. Reductions were maintained in both groups at both follow-up points. | Moderate intensity d = −0.45 (small) Sprint intervals: d = −0.35 (small) |

| de Oliveira et al., 2021 [24] | 60 | 30 min/single player volleyball exergame @ HR of 116–119(17–18) beats per min | multiplayer mode | STAI-T 38(13)—single player 35(13)—multiplayer | Pre, post | No anxiety reduction following either condition. | Single player: rB = 0.14 (small) Multiplayer: rB = 0.43 (medium) | |

| Morais et al., 2021 [23] | 20 | 45 min/dance exergame/vigorous intensity @ 75(9.8)% Hrmax | Intensity-matched treadmill | STAI-T 44.8(8) | Pre, immediately post, 10 min post | Anxiety significantly reduced in both conditions at 10 min post; exergame sig lower immediately post. | Time effect: d = 1.29 (large) | |

| Herzog et al., 2022 [17] | 88 | 30 min/cycle/moderate intensity @ 60–70% Hrmax | Watched nature documentary | STAI-S: 37.3(10.43) | Pre and post | Anxiety significantly reduced in both control and exercise conditions. | Insufficient data |

| Paper | Eligibility Criteria Specified • | Subjects Randomly Allocated | Concealed Allocation | Groups Similar at Baseline | Blinding of Subjects | Blinding of Therapist | Blinding of Assessors | Measurements Obtained from than 85% | All Subjects Completed the Treatment or Control as Allocated, or Intention to Treat | Results between Groups Are Reported | Both Point Measurements and Measurements of Variability | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LeBouthillier and Asmundson, 2015 [18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Broman-Fulks, et al., 2015 [21] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Meier and Welch, 2016 [22] | 1 ^ | 1 °~ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Cooper and Tomporowski, 2017 [20] | 1 ^ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Mason and Asmundson, 2018 [19] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lago et al., 2018 [16] | 1 | 1 °~ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| de Oliveira et al., 2021 [24] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Morais et al., 2021 [23] | 1 | 0 ° | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Herzog et al., 2022 [17] | 1 ^ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Connor, M.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Scanlon, O.K.; Harrison, O.K. The Effect of Acute Exercise on State Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Sports 2023, 11, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11080145

Connor M, Hargreaves EA, Scanlon OK, Harrison OK. The Effect of Acute Exercise on State Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Sports. 2023; 11(8):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11080145

Chicago/Turabian StyleConnor, Madeleine, Elaine A. Hargreaves, Orla K. Scanlon, and Olivia K. Harrison. 2023. "The Effect of Acute Exercise on State Anxiety: A Systematic Review" Sports 11, no. 8: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11080145

APA StyleConnor, M., Hargreaves, E. A., Scanlon, O. K., & Harrison, O. K. (2023). The Effect of Acute Exercise on State Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Sports, 11(8), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11080145