The Evolutionary Misfit: Evolution, Epigenetics, and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases

Abstract

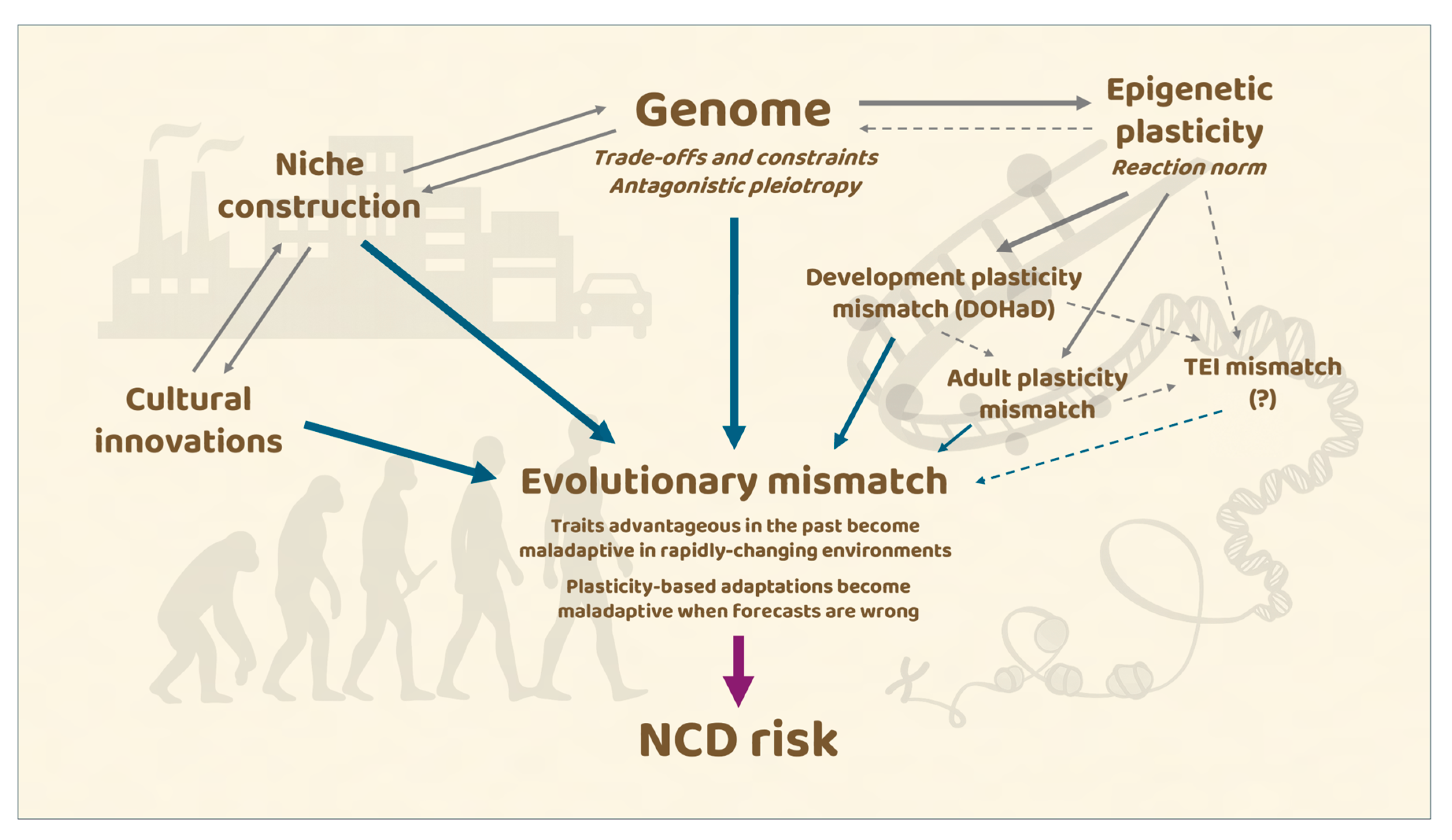

1. Introduction: Evolutionary Medicine and the “Misfit” Concept

2. Trade-Offs and Constraints: Why Bodies Are Not Optimal, but Good Enough

3. Aging, Evolutionary Theories and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases

3.1. Evolutionary Theories of Aging

3.2. Aging Before and After the Transition to Modernity

3.3. The Evolutionary Origins of Age-Related Disease: Mechanisms and Frameworks

3.4. Longevity, Mismatch, and the Modern Burden of NCDs

4. Developmental Plasticity, Epigenetic Inheritance, and Mismatch

4.1. Developmental Plasticity and the DOHaD Paradigm

4.2. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Promises and Controversies

4.3. Epigenetics and the Evolution of the Genome

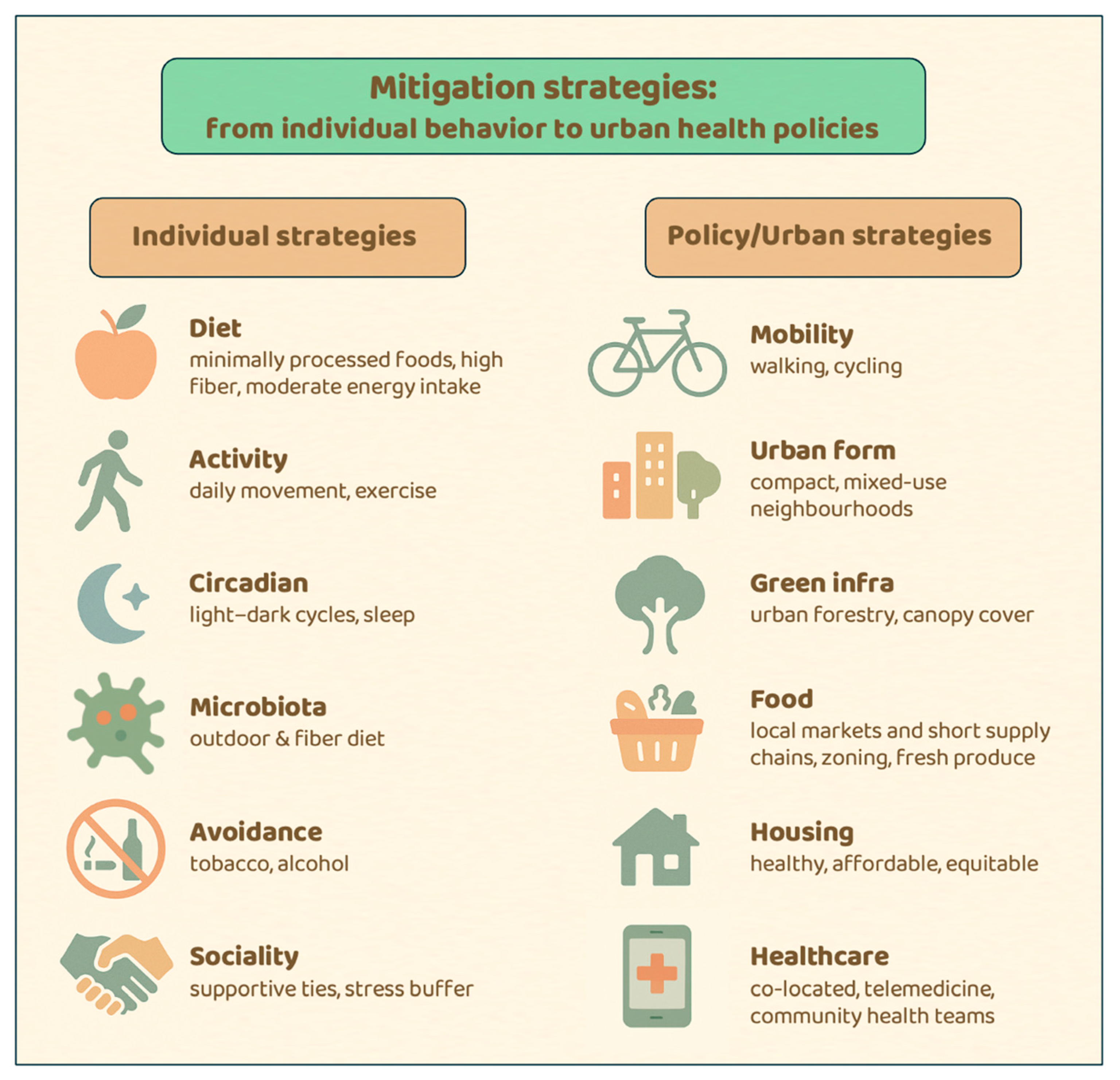

5. Mitigation Strategies: From Individual Behavior to Urban Health Policies

5.1. The Sustainability Challenge: Why Prevention Matters

5.2. Individual-Level Strategies: Aligning Daily Life with Human Biology

5.3. Policy-Level Strategies: Urban Health as Evolutionary Realignment

5.4. Governing Complexity: Towards a New Urban Health Science

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOHaD | Developmental origins of health and disease |

| DTA | Developmental theory of aging journals |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| SETS | Socio-ecological–technological systems |

| TEI | Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance |

References

- Nesse, R.M.; Williams, G.C. The dawn of Darwinian medicine. Q. Rev. Biol. 1991, 66, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, R.M.; Williams, G.C. Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine; Times Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, S.C.; Medzhitov, R. Evolutionary Medicine, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hallal, P.C.; Andersen, L.B.; Bull, F.C.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontzer, H.; Yamada, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Ainslie, P.N.; Andersen, L.F.; Anderson, L.J.; Arab, L.; Baddou, I.; Bedu_Addu, K.; Blaak, E.E.; et al. Daily energy expenditure through the human life course. Science 2021, 373, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Cheval, B.; Cody, R.; Colledge, F.; Hohberg, V.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Lang, C.; Looser, V.R.; Ludyga, S.; Stults-Kolehmainen, M.; et al. Psychophysiological foundations of human physical activity behavior and motivation: Theories, systems, mechanisms, evolution, and genetics. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 1213–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, G.A.W. Hygiene hypothesis and autoimmune diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 42, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferle, P.I.; Keber, C.U.; Cohen, R.M.; Garn, H. The hygiene hypothesis—Learning from but not living in the past. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 635935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garn, H.; Potaczek, D.P.; Pfefferle, P.I. The hygiene hypothesis and new perspectives: Current challenges meeting an old postulate. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 637087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdaca, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Gangemi, S. Hygiene hypothesis and autoimmune diseases: A narrative review of clinical evidences and mechanisms. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navara, K.J.; Nelson, R.J. The dark side of light at night: Physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.P., Jr.; McHill, A.W.; Birks, B.R.; Griffin, B.R.; Rusterholz, T.; Chinoy, E.D. Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1554–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, S.; Courtiol, A.; Lummaa, V.; Moorad, J.; Stearns, S. The transition to modernity and chronic disease: Mismatch and natural selection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laland, K.N.; Odling-Smee, J.; Myles, S. How culture shaped the human genome: Bringing genetics and the human sciences together. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodin, P. Immune-microbe interactions early in life: A determinant of health and disease long term. Science 2022, 376, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neel, J.V. Diabetes mellitus: A “thrifty” genotype rendered detrimental by “progress”? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1962, 14, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Low, F.M. Evolutionary and developmental mismatches are consequences of adaptive developmental plasticity in humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2019, 374, 20180109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, A.J.; Clark, A.G.; Dahl, A.W.; Devinsky, O.; Garcia, A.R.; Golden, C.D.; Kamau, J.; Kraft, T.S.; Lim, Y.A.L.; Martins, D.J.; et al. Applying an evolutionary mismatch framework to understand disease susceptibility. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Beedle, A.S. Early life events and their consequences for later disease: A life history and evolutionary perspective. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2007, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.K. The thrifty phenotype: An adaptation in growth or metabolism? Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2018, 30, e23112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justulin, L.A.; Zambrano, E.; Ong, T.P.; Ozanne, S.E. Early life epigenetic programming of health and disease through DOHaD perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1139283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Sadler-Riggleman, I.; Beck, D.; Skinner, M.K. Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease. Environ. Epigenetics 2018, 4, dvy016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-James, M.H.; Cavalli, G. Molecular mechanisms of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, D.P. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 1989, 299, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, J.F. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H.; Kuhn, C.; Feillet, H.; Bach, J.F. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: An update. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 160, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, B.; Hammad, H. The immunology of the allergy epidemic and the hygiene hypothesis. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penders, J.; Thijs, C.; Vink, C.; Stelma, F.F.; Snijders, B.; Kummeling, I.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Stobberingh, E.E. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.; Blaser, M.J. The human microbiome: At the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14691–14696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, M. Darwinian medicine: A case for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktipis, C.A.; Boddy, A.M.; Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.S.; Maley, C.C. Life history trade-offs in cancer evolution. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGregori, J. Evolved tumor suppression: Why are we so good at not getting cancer? Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3739–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Kim, D.R. Life history dynamics of evolving tumors: Insights into task specialization, trade-offs, and tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Magalhães, J.P. The evolution of cancer and ageing: A history of constraint. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. Evolutionary origins of depression: A review and reformulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 81, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B.; Badcock, C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008, 31, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.P.; van Vugt, M.; Colarelli, S.M. The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis: Implications for psychological science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoller, J.W.; Andreassen, O.A.; Edenberg, H.J.; Faraone, S.V.; Glatt, S.J.; Kendler, K.S. Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B.J. Evolutionary and genetic insights for clinical psychology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 78, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N.W.; Moore, A.J. Evolutionary consequences of social isolation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.K. Ecogeographical associations between climate and human body composition: Analyses based on anthropometry and skinfolds. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 147, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobiner, B. Living the paleofantasy? Evol. Educ. Outreach 2014, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, S.C. Trade-offs in life-history evolution. Funct. Ecol. 1989, 3, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, S.C. The Evolution of Life Histories; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, S.J. Constraints on phenotypic evolution. Am. Nat. 1992, 140, S85–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.C. Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution 1957, 11, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.; Trevathan, W. Birth, obstetrics and human evolution. BJOG 2002, 109, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevathan, W. Human Birth: An Evolutionary Perspective, 2nd ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, M.; Roseman, C.C. Complex and changing patterns of natural selection explain the evolution of the human hip. J. Hum. Evol. 2015, 85, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.D.; Collin, S.P.; Pugh, E.N. Evolution of the vertebrate eye: Opsins, photoreceptors, retina and eye cup. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, T.D. Evolution of the eye. Sci. Am. 2011, 305, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masland, R.H. The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron 2012, 76, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J.; Lewontin, R.C. The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. Proc. R. Soc. B 1979, 205, 581–598. [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R. Evolutionary perspectives on the obesity epidemic: Adaptive, maladaptive, and neutral viewpoints. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 33, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.C.K. Thrift: A guide to thrifty genes, thrifty phenotypes and thrifty norms. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R. Thrifty genes for obesity, an attractive but flawed idea, and an alternative perspective: The “drifty gene” hypothesis. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, R.M. Why has natural selection left us so vulnerable to anxiety and mood disorders? Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D. The moulding of senescence by natural selection. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 12, 12–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medawar, P.B. An Unsolved Problem of Biology; H.K. Lewis: London, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L. Evolution of ageing. Nature 1977, 270, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaître, J.F.; Moorad, J.; Gaillard, J.M.; Maklakov, A.A.; Nussey, D.H. A unified framework for evolutionary genetic and physiological theories of aging. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging: An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byars, S.G.; Stearns, S.C.; Boomsma, J.J. Opposite risk patterns for autism and schizophrenia are associated with normal variation in birth size: Phenotypic support for hypothesized diametric gene-dosage effects. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20140604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, L. The new biology of ageing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, T.; Partridge, L. Horizons in the evolution of aging. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillin, A.; Crawford, D.K.; Kenyon, C. Timing requirements for insulin/IGF-1 signaling in C. elegans. Science 2002, 298, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, M.; Benedetto, A.; Sornda, T.; Gilliat, A.F.; Au, C.; Zhang, Q.; van Schelt, S.; Petrache, A.L.; Wang, H.; de la Guardia, Y.; et al. C. elegans eats its own intestine to make yolk leading to multiple senescent pathologies. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Countdown 2030 Collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: Worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet 2018, 392, 1072–1088. [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Spencer, H.G. Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirtle, R.L.; Skinner, M.K. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, B.T.; Tobi, E.W.; Stein, A.D.; Putter, H.; Blauw, G.J.; Susser, E.S.; Slagboom, P.E.; Lumey, L.H. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17046–17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, E.; Raz, G. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: Prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution. Q. Rev. Biol. 2009, 84, 131–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, P.; Gluckman, P.; Hanson, M. The biology of developmental plasticity and the Predictive Adaptive Response hypothesis. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 2357–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, G.; Heard, E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 2019, 571, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, A.C.J.; van der Meulen, J.H.P.; Osmond, C.; Barker, D.J.P.; Bleker, O.P. Obesity at the age of 50 y in men and women exposed to famine prenatally. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumey, L.H.; Stein, A.D.; Susser, E. Prenatal famine and adult health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, I.C.G.; Cervoni, N.; Champagne, F.A.; D’Alessio, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Dymov, S.; Szyf, M.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaney, M.J. Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene x environment interactions. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entringer, S.; Buss, C.; Wadhwa, P.D. Prenatal stress, development, health and disease risk: A psychobiological perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Gomulkiewicz, R.; Kirkpatrick, M. Quantitative genetics and the evolution of reaction norms. Evolution 1992, 46, 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessells, C.M. Neuroendocrine control of life histories: What do we need to know to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2007, 363, 1589–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joschinski, J.; Bonte, D. Transgenerational plasticity and bet-hedging: A framework for reaction norm evolution. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 517183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barres, R.; Zierath, J.R. The role of diet and exercise in the transgenerational epigenetic landscape of T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.M.; Baccarelli, A.A. Environmental exposure and mitochondrial epigenetics: Study design and analytical challenges. Human. Genet. 2014, 133, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostaiza-Cardenas, J.; Tobar, A.C.; Carolina Costa, S.; Calero, D.S.; Carrera, A.L.; German Bermúdez, F.; Orellana-Manzano, A. Epigenetic modulation by lifestyle: Advances in diet, exercise, and mindfulness for disease prevention and health optimization. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1632999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; Reiner, A.P.; Aviv, A.; Raj, K.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Li, Y.; Stewart, J.D.; et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2019, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Basile, G.; Agodi, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet partially mediates socioeconomic differences in leukocyte LINE-1 methylation: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in Italian women. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reik, W.; Dean, W.; Walter, J. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science 2001, 293, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, E.; Martienssen, R.A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: Myths and mechanisms. Cell 2014, 157, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.K. Environmental stress and epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feil, R.; Fraga, M.F. Epigenetics and the environment: Emerging patterns and implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, V.L. Paramutation: From maize to mice. Cell 2007, 128, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, E.L.; Maures, T.J.; Ucar, D.; Hauswirth, A.G.; Mancini, E.; Lim, J.P.; Benayoun, B.A.; Shi, Y.; Brunet, A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2011, 479, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.F.; Lehner, B. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: A critical perspective. Front. Epigenetics Epigenomics 2024, 2, 1434253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsthemke, B. A critical view on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Lehrner, A.; Desarnaud, F.; Bader, H.N.; Makotkine, I.; Flory, J.Y.; Bierer, L.M.; Meaney, M.J. Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, C.J.; Quinn, E.B.; Hamadmad, D.; Dutton, C.L.; Al Nevell, L.; Binder, A.M.; Panter-Brick, C.; Dajani, R. Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anway, M.D.; Cupp, A.S.; Uzumcu, M.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science 2005, 308, 1466–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.E.; Anway, M.D.; Stanfield, J.; Skinner, M.K. Transgenerational epigenetic effects of the endocrine disruptor vinclozolin on pregnancies and female adult-onset disease. Reproduction 2008, 135, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdge, G.C.; Hoile, S.P.; Uller, T.; Thomas, N.A.; Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Lillycrop, K.A. Progressive, transgenerational changes in offspring phenotype and epigenotype following nutritional transition. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öst, A.; Lempradl, A.; Casas, E.; Weigert, M.; Tiko, T.; Deniz, M.; Pantano, L.; Boenisch, U.; Itskov, P.M.; Stoeckius, M.; et al. Paternal diet defines offspring chromatin state and intergenerational obesity. Cell 2014, 159, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.E.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity susceptibility. TEM 2020, 31, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, A.B.; Morgan, C.P.; Bronson, S.L.; Revello, S.; Bale, T.L. Paternal stress exposure alters sperm microRNA content and reprograms offspring HPA stress axis regulation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 9003–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, J.L.M.; Beck, D.; Ben Maamar, M.; Nilsson, E.; Skinner, M.K. Ancestral plastics exposure induces transgenerational disease-specific sperm epigenome-wide association biomarkers. Environ. Epigenetics 2021, 7, dvab023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uller, T. Parental effects in development and evolution. In Parental Effects in Development and Evolution; The Evolution of Parental Care; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, P.; Barker, D.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Deb, D.; D’Udine, B.; Foley, R.A.; Gluckman, P.; Godfrey, K.; Kirkwood, T.; Mirazón Lahr, M.; et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature 2004, 430, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Spencer, H.G.; Bateson, P. Environmental influences during development and their later consequences for health and disease: Implications for the interpretation of empirical studies. Proc. R. Soc. B 2005, 272, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.A.; Skinner, M.K. Developmental origins of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. Environ. Epigenetics 2016, 2, dvw002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisato, V.; D’Aversa, E.; Salvatori, F.; Sbracia, M.; Peluso, G.; Scarpellini, F.; Gemmati, D. Epigenetic mechanisms in maternal-fetal crosstalk: Inter-and trans-generational inheritance. Epigenomics 2025, 17, 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, A.; Rando, O.J. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.P.; Jørgensen, P.S.; Kinnison, M.T.; Bergstrom, C.T.; Denison, R.F.; Gluckman, P.; Smith, T.B.; Strauss, S.Y.; Tabashnik, B.E. Applying evolutionary biology to address global challenges. Science 2014, 346, 1245993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J.; McElreath, R. The evolution of cultural evolution. Evol. Anthropol. 2003, 12, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laland, K.N.; Odling-Smee, F.J.; Feldman, M.W. Niche construction, biological evolution, and cultural change. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 23, 131–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creanza, N.; Kolodny, O.; Feldman, M.W. Cultural evolutionary theory: How culture evolves and why it matters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7782–7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebollo, R.; Romanish, M.T.; Mager, D.L. Transposable elements: An abundant and natural source of regulatory sequences for host genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuong, E.B.; Elde, N.C.; Feschotte, C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: From conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, G.; Burns, K.H.; Gehring, M.; Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A.; Hammell, M.; Imbeault, M.; Izsvák, Z.; Levin, H.L.; Macfarlan, T.S.; et al. Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sved, J.; Bird, A. The expected equilibrium of the CpG dinucleotide in vertebrate genomes under a mutation model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 4692–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, B.K.; Miller, J.H. Mutagenic deamination of cytosine residues in DNA. Nature 1980, 287, 560–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio, N.; Barau, J.; Teissandier, A.; Walter, M.; Borsos, M.; Servant, N.; Bourc’his, D. DNA methylation restrains transposons from adopting a chromatin signature permissive for meiotic recombination. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmátal, L.; Gabriel, S.I.; Mitsainas, G.P.; Martinez-Vargas, J.; Ventura, J.; Searle, J.B.; Schultz, R.M.; Lampson, M.A. Centromere strength provides the cell biological basis for meiotic drive and karyotype evolution in mice. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2295–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.K. Environmental epigenetics and a unified theory of the molecular aspects of evolution: A neo-Lamarckian concept that facilitates neo-Darwinian evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, E.J. Inherited epigenetic variation-revisiting soft inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Ebbeling, C.B. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity: Beyond “calories in, calories out”. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.Y.; Chung, S.T.; Costa, E.; Courville, A.; Darcey, V.; et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Louzada, M.L.; Steele-Martinez, E.; Cannon, G.; Andrade, G.C.; Baker, P.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Bonaccio, M.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Khandpur, N.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and human health: The main thesis and the evidence. Lancet 2025, 406, 2667–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Vogel, R.; Lavie, C.J.; Cordain, L. Achieving hunter-gatherer fitness in the 21st century: Back to the future. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Brown, W.J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, A.; GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing New and Emerging Products; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Dudley, R.; Maro, A. Human evolution and dietary ethanol. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerlo, P.; Sgoifo, A.; Suchecki, D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: Effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med. Rev. 2008, 12, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.C.; Ong, J.L.; Leong, R.L.; Gooley, J.J.; Chee, M.W. Cognitive performance, sleepiness, and mood in partially sleep deprived adolescents: The need for sleep study. Sleep 2016, 39, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Akil, H. Revisiting the stress concept: Implications for affective disorders. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, J.; Lucente, M.; Sonino, N.; Fava, G.A. Allostatic load and its impact on health: A systematic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 90, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Setting Global Research Priorities for Urban Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Giles-Corti, B.; Moudon, A.V.; Lowe, M.; Cerin, E.; Boeing, G.; Frumkin, H.; Salvo, D.; Foster, S.; Kleeman, A.; Bekessy, S.; et al. What next? Expanding our view of city planning and global health, and implementing and monitoring evidence-informed policy. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e919–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, D.; Norberciak, M.; Morales-Zamora, E. Advancing health equity through 15-min cities and chrono-urbanism. J. Urban Health 2024, 101, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.; Thompson, J.; de Sá, T.H.; Ewing, R.; Mohan, D.; McClure, R.; Roberts, I.; Tiwari, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sun, X.; et al. Land use, transport, and population health: Estimating the health benefits of compact cities. Lancet 2016, 388, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, J.A.; Tadaki, M.; Vardoulakis, S.; Arbuthnott, K.; Coutts, A.; Demuzere, M.; Dirks, K.N.; Heaviside, C.; Lim, S.; Macintyre, H.; et al. Health and climate related ecosystem services provided by street trees. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Helbich, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y. Urban greenery and mental wellbeing in adults: Cross-sectional mediation analyses on multiple pathways across different greenery measures. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Bardhan, R. Cooling efficacy of trees across cities is determined by background climate, urban morphology, and tree trait. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ordoñez, C.; Elena Garcia-Nevado, E.; Coch Morganti, M. Heat stress in social housing districts: Tree cover-built form interactions modulate urban heat. Build. Cities 2025, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Lee, K.; Shin, S. Access to urban green space in cities of the Global South: A systematic literature review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Meitner, M.J.; Girling, C.; Sheppard, S.R.J.; Lu, Y. Who has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 US cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Moudon, A.V.; Lowe, M.; Adlakha, D.; Cerin, E.; Boeing, G.; Higgs, C.; Arundel, J.; Liu, S.; Hinckson, E.; et al. Creating healthy and sustainable cities: What gets measured, gets done. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e782–e785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoine, T.; Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.J.; Monsivais, P. Examining the interaction of fast-food outlet exposure and income on diet and obesity: Evidence from 51,361 UK Biobank participants. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulya, S.P.; Putro, H.P.H.; Hudalah, D. Review of peri-urban agriculture as a regional ecosystem service. Geogr. Sustain. 2023, 4, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Hara, Y.; Thaitakoo, D. Linking food and land systems for sustainable peri-urban agriculture in Bangkok Metropolitan Region. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, C.B.; Hernández, D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 243, 112571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, E.H.; Constantino, S.M.; Centeno, M.A.; Elmqvist, T.; Weber, E.U.; Levin, S.A. Governing sustainable transformations of urban social-ecological-technological systems. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Cook, E.M.; Berbés-Blázquez, M.; Cheng, C.; Grimm, N.B.; Andersson, E.; Barbosa, O.; Chandler, D.G.; Chang, H.; Chester, M.V.; et al. A social-ecological-technological systems framework for urban ecosystem services. One Earth 2022, 5, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amatori, S. The Evolutionary Misfit: Evolution, Epigenetics, and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040051

Amatori S. The Evolutionary Misfit: Evolution, Epigenetics, and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases. Epigenomes. 2025; 9(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmatori, Stefano. 2025. "The Evolutionary Misfit: Evolution, Epigenetics, and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases" Epigenomes 9, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040051

APA StyleAmatori, S. (2025). The Evolutionary Misfit: Evolution, Epigenetics, and the Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases. Epigenomes, 9(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040051