The Epigenomic Impact of Quantum Dots: Emerging Biosensors and Potential Disruptors

Abstract

1. Introduction

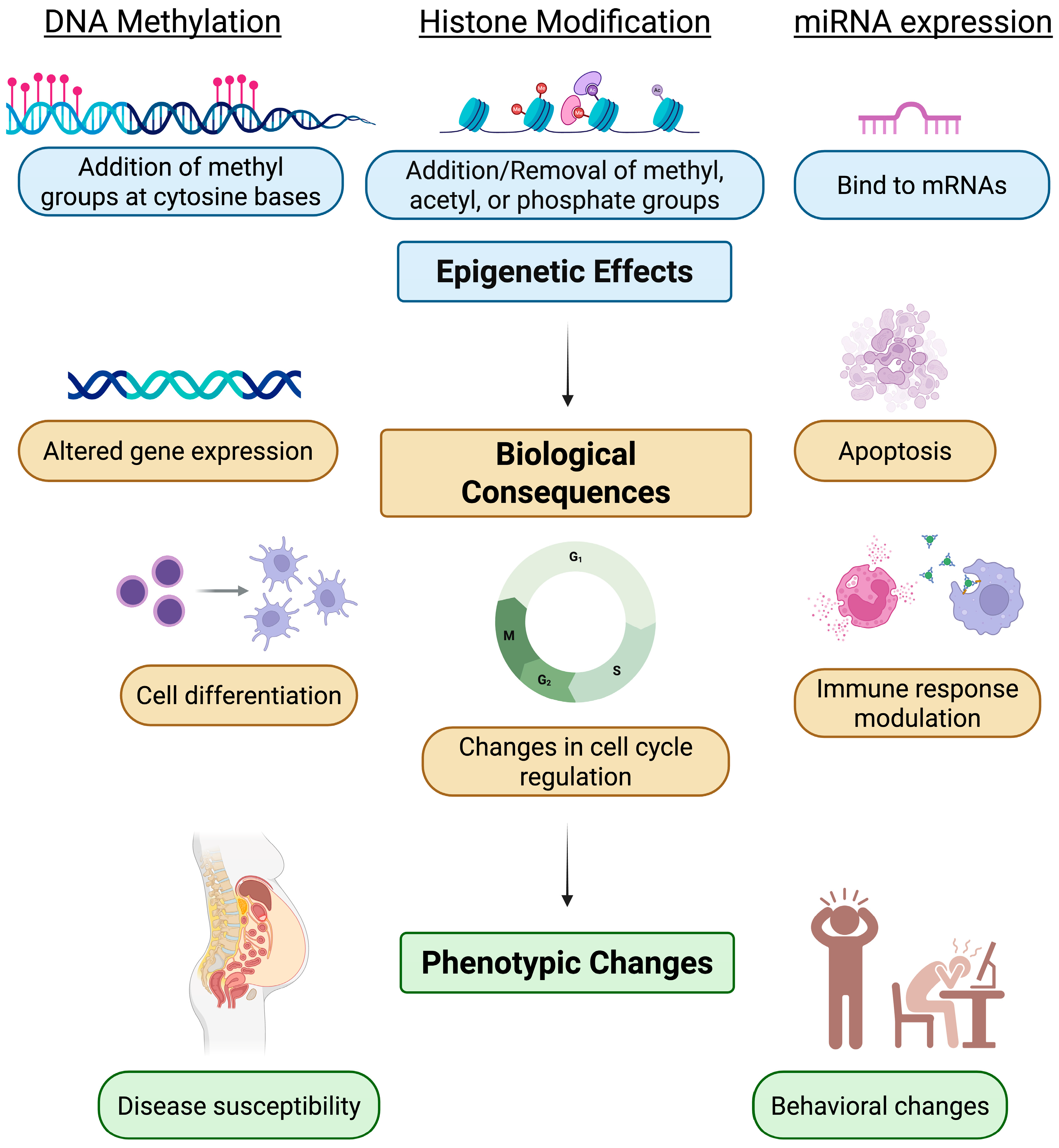

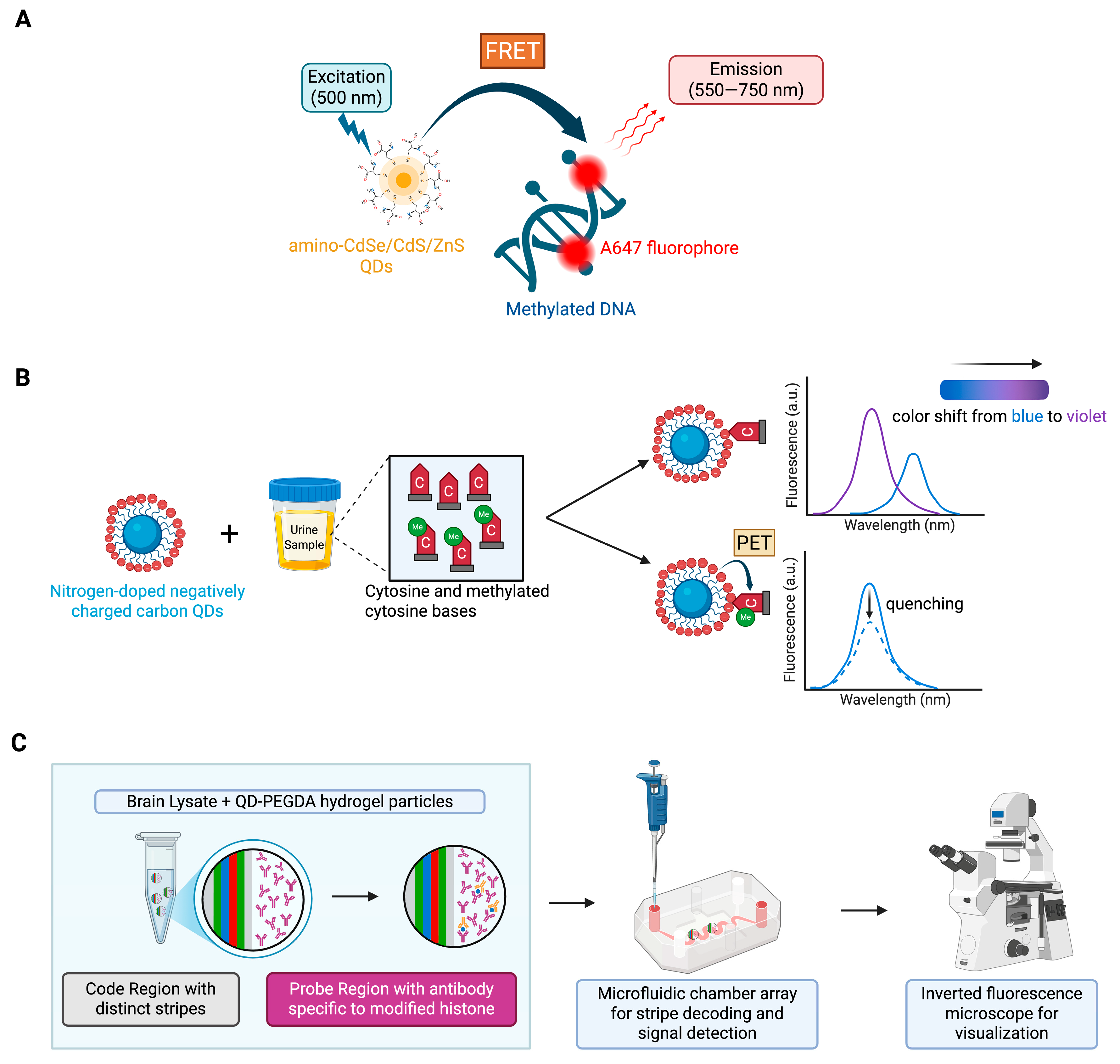

2. QDs as Biosensors for Epigenetic Process Detection

2.1. QD-Based Biosensors for DNA Methylation

2.2. QD-Based Biosensors for Histone Modification

2.3. QD-Based Biosensors for miRNA Expression

2.4. Discussion on the Usability of QDs as a Biosensor of Epigenomics

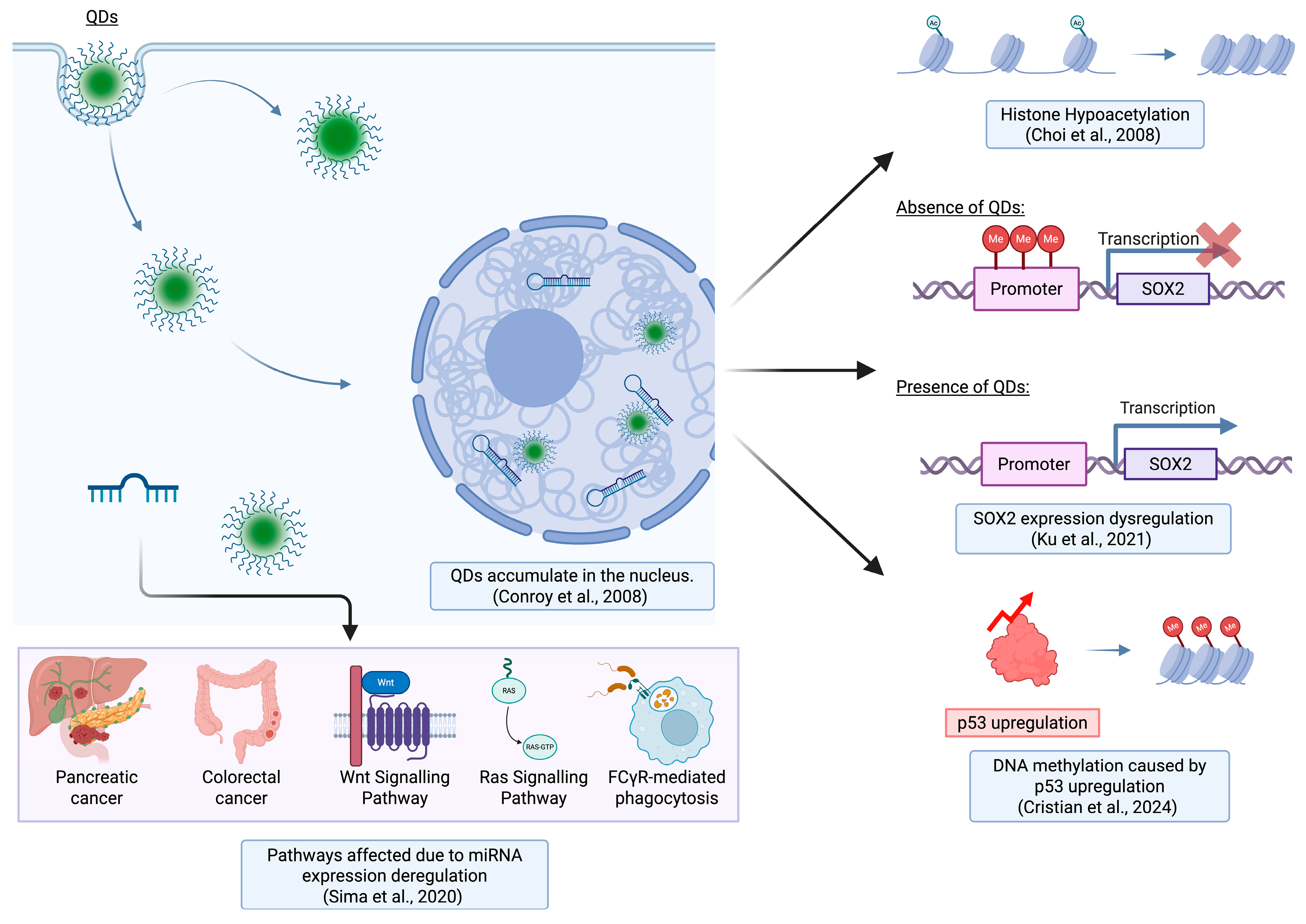

3. Epigenetic Changes Caused by QDs

3.1. General Outline of Epigenetic Research Combined with QD-Induced Changes in Histone Modifications

3.2. QD-Mediated Dysregulation of miRNA Expression

3.3. QD-Induced Changes in DNA Methylation

| Epigenetic Target | Cell Model | QDs Used | Key Aspects | Author, Year [Citation] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone modification | MCF-7 | CdTe QDs |

| Choi et al., 2008 [60] |

| Histone interaction | THP-1 | CdTe QDs | Cellular tracking of QDs in nuclear areas where QDs show histone affinity. | Conroy et al., 2008 [61] |

| Gene (mRNA, miRNA) expression, DNA methylation | HEL 12469 | CDs (nCDs and pCDs) | Charge-based comparison of CDs on epigenome where nCDs caused more changes in gene expression. | Sima et al., 2020 [63] |

| DNA methylation | mESCs | GQDs | QDs disrupt embryonic stem cell differentiation by altering DNA methylation of Sox2 promoter. | Ku et al., 2021 [64] |

| DNA methylation, histone modification | Mouse (in vivo) | Si QDs | Epigenetic changes induced by QDs resulted in tissue-specific (lungs vs. spleen) responses. | Cristian et al., 2024 [65] |

| miRNA biogenesis | NIH/3T3 | CdTe QDs |

| Li et al., 2011 [66] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| miRNA | Micro-RNA |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| FRET | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer |

| A647 | Alexa fluor-647 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| MS-HRM | Methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting |

| PEGDA | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate |

| 2Me-H3K9 | Dimethylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 |

| 3Me-H3K9 | Trimethylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 |

| Ac-H3K9 | Acetylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 |

| SA-PE | Streptavidin-phycoerythrin |

| EXPAR | Exponential amplification reaction |

| HCR | Hybridization chain reaction |

| 5-mC | 5-methylcytosine |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| ChIP-seq | Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing |

| MLPA | Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification |

| 5-hmC | 5-hydroxymethylcytosine |

| OxBS-seq | Oxidative bisulfite sequencing |

| TAB-seq | TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing |

| CdTe | Cadmium telluride |

| Ac-H3 | Acetylated histone 3 |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| TSA | Trichostatin A |

| WGBS | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing |

| FLIM | Fluorescent lifetime imaging |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| DNMTs | DNA methytransferases |

| Pri-miRNAs | Primary miRNAs |

| Pre-miRNAs | Precursor miRNAs |

| nCDs | Negatively charged carbon dots |

| pCDs | Positively charged carbon dots |

| GQDs | Graphene quantum dots |

| mESCs | Mouse embryonic stem cells |

| Si | Silicon |

References

- Waddington, C.H. The epigenotype. 1942. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronick, E.; Hunter, R.G. Waddington, Dynamic Systems, and Epigenetics. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuebel, K.; Gitik, M.; Domschke, K.; Goldman, D. Making Sense of Epigenetics. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 19, pyw058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Aboud, N.M.; Tupper, C.; Jialal, I. Genetics, Epigenetic Mechanism; StatPearls: Petersburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bure, I.V.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Kuznetsova, E.B. Histone Modifications and Non-Coding RNAs: Mutual Epigenetic Regulation and Role in Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E.R.; Nolan, C.M. Epigenetics and gene expression. Heredity 2010, 105, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaughan, J.A.; McKnight, A.J.; Courtney, A.E.; Maxwell, A.P. Epigenetics: Time to translate into transplantation. Transplantation 2012, 94, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoran, M.; Nemcova, L.; Kalous, J. An Interplay between Epigenetics and Translation in Oocyte Maturation and Embryo Development: Assisted Reproduction Perspective. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 38, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, Y.A.; Khamis, A.M.; Kulakovskiy, I.V.; Ba-Alawi, W.; I Bhuyan, S.; Kawaji, H.; Lassmann, T.; Harbers, M.; Forrest, A.R.; Bajic, V.B.; et al. Effects of cytosine methylation on transcription factor binding sites. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutskov, V.; Felsenfeld, G. Silencing of transgene transcription precedes methylation of promoter DNA and histone H3 lysine 9. EMBO J. 2003, 23, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.; Lau, P. Epigenetic Regulation by Histone Methylation and Histone Variants. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratti, M.; Lampis, A.; Ghidini, M.; Salati, M.; Mirchev, M.B.; Valeri, N.; Hahne, J.C. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as New Tools for Cancer Therapy: First Steps from Bench to Bedside. Target. Oncol. 2020, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanek, J.; Tretyn, A. MicroRNA-Mediated Regulation of Histone-Modifying Enzymes in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; Badiye, A.; Vajpayee, K.; Kapoor, N. Genotoxic Potential of Nanoparticles: Structural and Functional Modifications in DNA. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 728250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, F.; Meng, W.; White, J.C.; Holden, P.A.; Xing, B. Engineered nanoparticles may induce genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13212–13214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsiedel, R.; Honarvar, N.; Seiffert, S.B.; Oesch, B.; Oesch, F. Genotoxicity testing of nanomaterials. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 14, e1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedda, M.R.; Babele, P.K.; Zahra, K.; Madhukar, P. Epigenetic Aspects of Engineered Nanomaterials: Is the Collateral Damage Inevitable? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M.I.; Valdés, A.; Fernández, A.F.; Torrecillas, R.; Fraga, M.F. The effect of exposure to nanoparticles and nanomaterials on the mammalian epigenome. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogribna, M.; Hammons, G. Epigenetic Effects of Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimov, A.I.; Onushchenko, A.A.; Ekimov, A.I.; Onushchenko, A.A. Quantum size effect in three-dimensional microscopic semiconductor crystals. JETPL 1981, 34, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, C.E.; Zrazhevskiy, P.; Bagalkot, V.; Gao, X. Quantum dots as a platform for nanoparticle drug delivery vehicle design. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 65, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrazhevskiy, P.; Sena, M.; Gao, X. Designing multifunctional quantum dots for bioimaging, detection, and drug delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4326–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairdolf, B.A.; Smith, A.M.; Stokes, T.H.; Wang, M.D.; Young, A.N.; Nie, S. Semiconductor Quantum Dots for Bioimaging and Biodiagnostic Applications. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2013, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Q.; Wang, Z.-G.; Fu, D.-D.; Zhang, J.-M.; Liu, H.-Y.; Liu, S.-L.; Pang, D.-W. Quantum Dots Tracking Endocytosis and Transport of Proteins Displayed by Mammalian Cells. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 7567–7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, Z.L.; Pang, D.W. Tracking single viruses infecting their host cells using quantum dots. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chen, T. A Review of in vivo Toxicity of Quantum Dots in Animal Models. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 8143–8168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wang, L.; Rehberg, M.; Stoeger, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Applications and Immunological Effects of Quantum Dots on Respiratory System. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 795232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, M.S.; Zahra, Z.; Salawu, O.A.; Burgess, R.M.; Ho, K.T.; Adeleye, A.S. Assessing the Environmental Effects Related to Quantum Dot Structure, Function, Synthesis and Exposure. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2022, 9, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, M. Identification of potential circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks in response to graphene quantum dots in microglia by microarray analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.H.; Bailey, V.; Liu, K. Quantum dots and microfluidic single-molecule detection for screening genetic and epigenetic cancer markers in clinical samples. Micro- Nanotechnol. Sens. Syst. Appl. III 2011, 8031, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.H. Quantum Dot Enabled Molecular Sensing and Diagnostics. Theranostics 2012, 2, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandale, P.; Choudhary, N.; Singh, J.; Sharma, A.; Shukla, A.; Sriram, P.; Soni, U.; Singla, N.; Barnwal, R.P.; Singh, G.; et al. Fluorescent quantum dots: An insight on synthesis and potential biological application as drug carrier in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, F.; Wu, Z.; Lu, S.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, X.; Mao, H. Highly sensitive detection of DNA methylation levels by using a quantum dot-based FRET method. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 17547–17555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thonghlueng, J.; Ngernpimai, S.; Chuaephon, A.; Phanchai, W.; Wiwasuku, T.; Wanna, Y.; Wiratchawa, K.; Intharah, T.; Thanan, R.; Sakonsinsiri, C.; et al. Dual-Responsive Carbon Quantum Dots for the Simultaneous Detection of Cytosine and 5-Methylcytosine Interpreted by a Machine Learning-Assisted Smartphone. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 40141–40152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.Y.; Son, C.H.; Kim, B.S.; Tag, S.H.; Nam, E.; Shin, H.; Kim, S.H.; Gang, H.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.; et al. Multiplexed Detection of Epigenetic Markers Using Quantum Dot (QD)-Encoded Hydrogel Microparticles. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4259–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molano, M.; Machalek, D.A.; Phillips, S.; Tan, G.; Garland, S.M.; Hawkes, D.; Balgovind, P.; Haqshenas, R.; Badman, S.G.; Bolnga, J.; et al. DNA methylation at individual CpG-sites of EPB41L3, HTERT and FAM19A4 are useful for detection of cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) or worse: Analysis of individual CpG-sites outperforms averaging. Tumour. Virus Res. 2024, 18, 200288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanwar, S.; Deogade, A. 5-Methylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Signatures Underlying Pediatric Cancers. Epigenomes 2019, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, A.; Chopra, P.; Alisch, R.S. Species-specific 5 mC and 5 hmC genomic landscapes indicate epigenetic contribution to human brain evolution. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 335786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.Y. Sensitive Detection of microRNA with Isothermal Amplification and a Single-Quantum-Dot-Based Nanosensor. Anal. Chem. 2011, 84, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Dadmehr, M.; Hosseini, M. Fluorescence-based detection of Let-7a miRNA through HCR-based approach upon the in situ interaction of AuNPs@CdS QDs and FRET mechanism. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabian, R.; Arshad, V.; Ahmadi, A.; Saeedi, P.; Jamalkandi, S.A.; Alivand, M.R. Laboratory methods to decipher epigenetic signatures: A comparative review. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2021, 26, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Xiao, L.; Wang, H. Advances of Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification Technology in Molecular Diagnostics. Biotechniques 2022, 73, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crary-Dooley, F.K.; Tam, M.E.; Dunaway, K.W.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Schmidt, R.J.; LaSalle, J.M. A comparison of existing global DNA methylation assays to low-coverage whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for epidemiological studies. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.; Buckberry, S.; Lister, R. Approaches for the Analysis and Interpretation of Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing Data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1767, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouil, Q.; Keniry, A. Latest techniques to study DNA methylation. Essays Biochem. 2019, 63, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshpour, M.; Karimi, B.; Omidfar, K. Simultaneous detection of gastric cancer-involved miR-106a and let-7a through a dual-signal-marked electrochemical nanobiosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 109, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Pan, L.-Y.; Li, Y.; Zou, X.; Liu, B.-J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, C.-Y. Deacetylation-activated construction of single quantum dot-based nanosensor for sirtuin 1 assay. Talanta 2021, 224, 121918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adampourezare, M.; Saadati, A.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Dehghan, G.; Feizi, M.A.H. Reliable recognition of DNA methylation using bioanalysis of hybridization on the surface of Ag/GQD nanocomposite stabilized on poly (β-cyclodextrin): A new platform for DNA damage studies using genosensor technology. J. Mol. Recognit. 2022, 35, e2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, D.L.; Hu, J.; Qiu, J.G.; Zhang, C.Y. Hydroxymethylation-Specific Ligation-Mediated Single Quantum Dot-Based Nanosensors for Sensitive Detection of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Cancer Cells. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 9785–9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, H.; Fang, L.; Peng, K.; et al. A novel photoelectrochemical strategy for ultrasensitive and simultaneous detection of 5-methylcytosine and N6-methyladenosine based on proximity binding-triggered assembly MNAzyme -mediated HRCA. Mikrochim. Acta 2025, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, R.; Li, L.S. Recent progress on eco-friendly quantum dots for bioimaging and diagnostics. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 10309–103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y. Environmentally friendly synthesis of quantum dots and their applications in diverse fields from the perspective of environmental compliance: A review. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Tong, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Yu, P.; Ji, H.; Niu, X.; Wang, Z.M. Eco-Friendly Colloidal Quantum Dot-Based Luminescent Solar Concentrators. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Baul, A.; Amar, A.; Wadhwa, R.; Kumar, S.; Varma, R.S. Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Pathways to Photoluminescent Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs). Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohs, A.M.; Duan, H.; Kairdolf, B.A.; Smith, A.M.; Nie, S. Proton-Resistant Quantum Dots: Stability in Gastrointestinal Fluids and Implications for Oral Delivery of Nanoparticle Agents. Nano Res. 2009, 2, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Pons, T.; Lequeux, N.; Dubertret, B. Quantum dots–DNA bioconjugates: Synthesis to applications. Interface Focus 2016, 6, 20160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, E.L.; Tomlinson, I.D.; Mason, J.; Gresch, P.; Warnement, M.R.; Wright, D.; Sanders-Bush, E.; Blakely, R.; Rosenthal, S.J. Surface modification to reduce nonspecific binding of quantum dots in live cell assays. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005, 16, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.O.; Brown, S.E.; Szyf, M.; Maysinger, D. Quantum dot-induced epigenetic and genotoxic changes in human breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 86, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, J.; Byrne, S.J.; Gun’Ko, Y.K.; Rakovich, Y.P.; Donegan, J.F.; Davies, A.; Kelleher, D.; Volkov, Y. CdTe Nanoparticles Display Tropism to Core Histones and Histone-Rich Cell Organelles. Small 2008, 4, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, N.; Chand, A.; Braun, E.; Keyes, C.; Wu, Q.; Kim, K. Interactions between Quantum Dots and G-Actin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, M.; Vrbova, K.; Zavodna, T.; Honkova, K.; Chvojkova, I.; Ambroz, A.; Klema, J.; Rossnerova, A.; Polakova, K.; Malina, T.; et al. The Differential Effect of Carbon Dots on Gene Expression and DNA Methylation of Human Embryonic Lung Fibroblasts as a Function of Surface Charge and Dose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, T.; Hao, F.; Yang, X.; Rao, Z.; Liu, Q.S.; Sang, N.; Faiola, F.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, G. Graphene Quantum Dots Disrupt Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation by Interfering with the Methylation Level of Sox2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3144–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristian, R.-E.; Balta, C.; Herman, H.; Ciceu, A.; Trica, B.; Sbarcea, B.G.; Miutescu, E.; Hermenean, A.; Dinischiotu, A.; Stan, M.S. Exploring In Vivo Pulmonary and Splenic Toxicity Profiles of Silicon Quantum Dots in Mice. Materials 2024, 17, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, Y.; Liang, G.; Wang, Y.; Huang, N.; Xiao, Z. MicroRNAs as participants in cytotoxicity of CdTe quantum dots in NIH/3T3 cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3807–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Branicky, R.; Noë, A.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovy, A.; Spiro, A.; McCarthy, R.; Shipony, Z.; Aylon, Y.; Allton, K.; Ainbinder, E.; Furth, N.; Tanay, A.; Barton, M.; et al. p53 is essential for DNA methylation homeostasis in naïve embryonic stem cells, and its loss promotes clonal heterogeneity. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estève, P.O.; Chin, H.G.; Pradhan, S. Human maintenance DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase and p53 modulate expression of p53-repressed promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, J.; Li, J.; Tian, D.; Gu, L.; Zhou, M. Methylation of RASSF1A gene promoter is regulated by p53 and DAXX. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Epigenetic Target | Detection Platform | QD Function | Key Aspects | Author, Year [Citation] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | QD-FRET system | QDs are donors that generate FRET signal to A647-labeled DNA. | Convenient, cost- and time-effective biosensor that enables highly sensitive early detection of DNA methylation in cancer tissues. | Ma et al., 2015 [35] |

| DNA methylation: Cytosine (C) and 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) | Nitrogen-doped CQD fluorescent sensor | Fluorescent label for detection. | Highly specific for detection of C and 5-mC in urine samples where fluorescent intensity is enhanced in presence of more C, in contrast to fluorescent quenching caused by 5-mC. | Thonghleung et al., 2023 [36] |

| Histone modification | QD-PEGDA hydrogel microparticles | QDs that emit red, green, and blue light are embedded in PEGDA hydrogel microparticles for color coding and detection using a single wavelength. | Highly sensitive simultaneous detection of multiple modified histones from the brain of cocaine exposed mice. | Yeom et al., 2016 [37] |

| miRNA expression | QD-FRET system | QDs are donors to induce Cy5 FRET signal | Highly sensitive and specific biosensor with possibility of being used as a multiplex detection system. | Zhang et al., 2011 [41] |

| miRNA expression | AuNPs@CdS QD FRET system | QDs are FRET donors measuring fluorescence quenching. | Enzyme-free and relatively simple biosensor for low-cost detection of let-7a miRNA. | Hosseini et al., 2025 [42] |

| miRNA expression | CdSe@CdS/TMC/Fe3O4 nanocomposites | QDs generated electrochemical signal proportional to concentration of let-7a miRNA. | PCR-free biosensor for detection of gastric cancer-specific miRNAs. | Daneshpour et al., 2018 [48] |

| Histone modification: Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) | Cy5-labeled peptide substrate with a streptavidin-coated QD nanosensor | Peptides assemble on QD surface via streptavidin and induce FRET from QD to Cy5. | Highly sensitive novel deacetylation-activated QD sensor that achieves label-free detection of SIRT1 and its inhibitors. | Hu et al., 2021 [49] |

| DNA methylation | poly (β-cyclodextrin)—Ag/GQD nanocomposite | GQDs were hybridized with Ag nanoparticles as a substrate for electrode. | Detection of methylated and unmethylated sequences as well as sequences containing mismatch with very low detection limit. | Adampourezare et al., 2022 [50] |

| DNA methylation: 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) | QD-FRET system | biotin-/Cy5-labeled ssDNA assemble on QD surface via streptavidin and induce FRET for generation of Cy5 signal. | Very low detection limit of 5-hmC DNA in complex mixtures without adding reagents or specific antibiotics. | Wang et al., 2022 [51] |

| DNA methylation (5-mC) and RNA modification (N6-methyladenosine) | UiO-66@CdTe@AuNPs photoelectrochemical biosensor | CdTe QDs are used as light-absorbing semiconductors, resulting in efficient conversion of high photons and electrons that amplifies the sensor signal. | Robust and simultaneous detection of DNA methylation and RNA modification based on antibody-specific recognition. | Hu et al., 2025 [52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chand, A.; Kim, K. The Epigenomic Impact of Quantum Dots: Emerging Biosensors and Potential Disruptors. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040050

Chand A, Kim K. The Epigenomic Impact of Quantum Dots: Emerging Biosensors and Potential Disruptors. Epigenomes. 2025; 9(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleChand, Abhishu, and Kyoungtae Kim. 2025. "The Epigenomic Impact of Quantum Dots: Emerging Biosensors and Potential Disruptors" Epigenomes 9, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040050

APA StyleChand, A., & Kim, K. (2025). The Epigenomic Impact of Quantum Dots: Emerging Biosensors and Potential Disruptors. Epigenomes, 9(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes9040050