Normal Spiral Grand-Design Morphologies in Self-Consistent N-Body Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

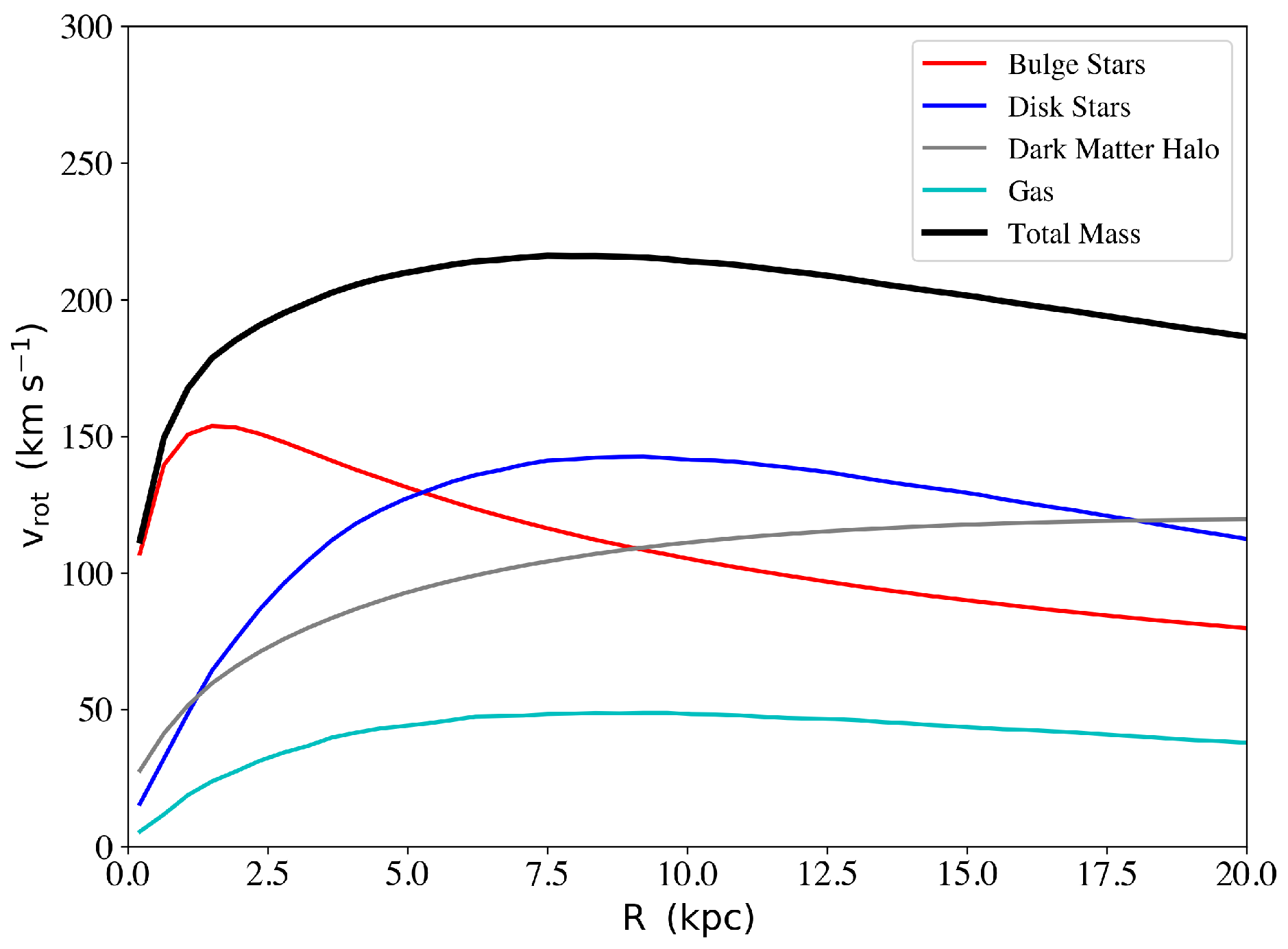

2. The Model and the Method

3. Results

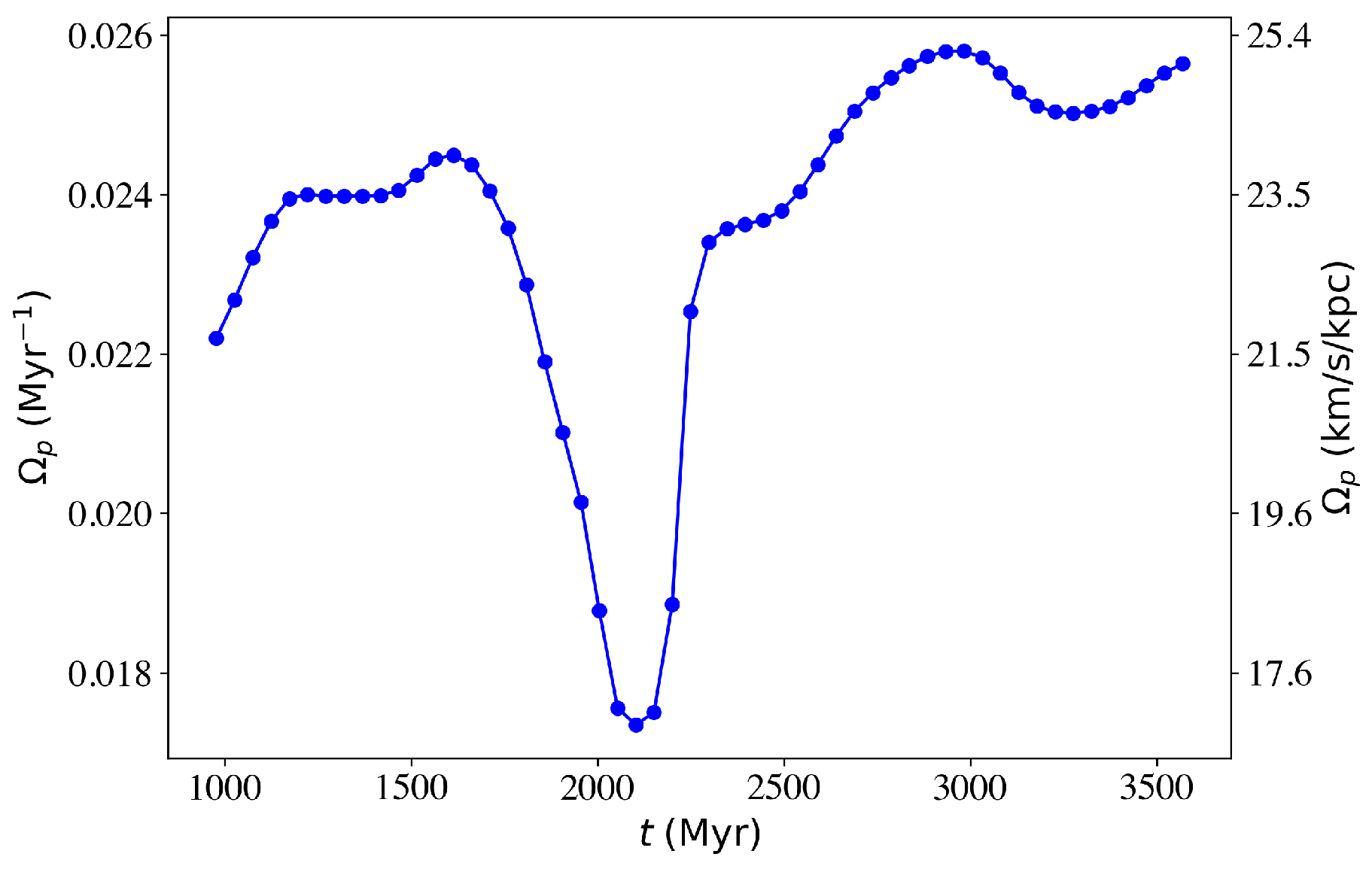

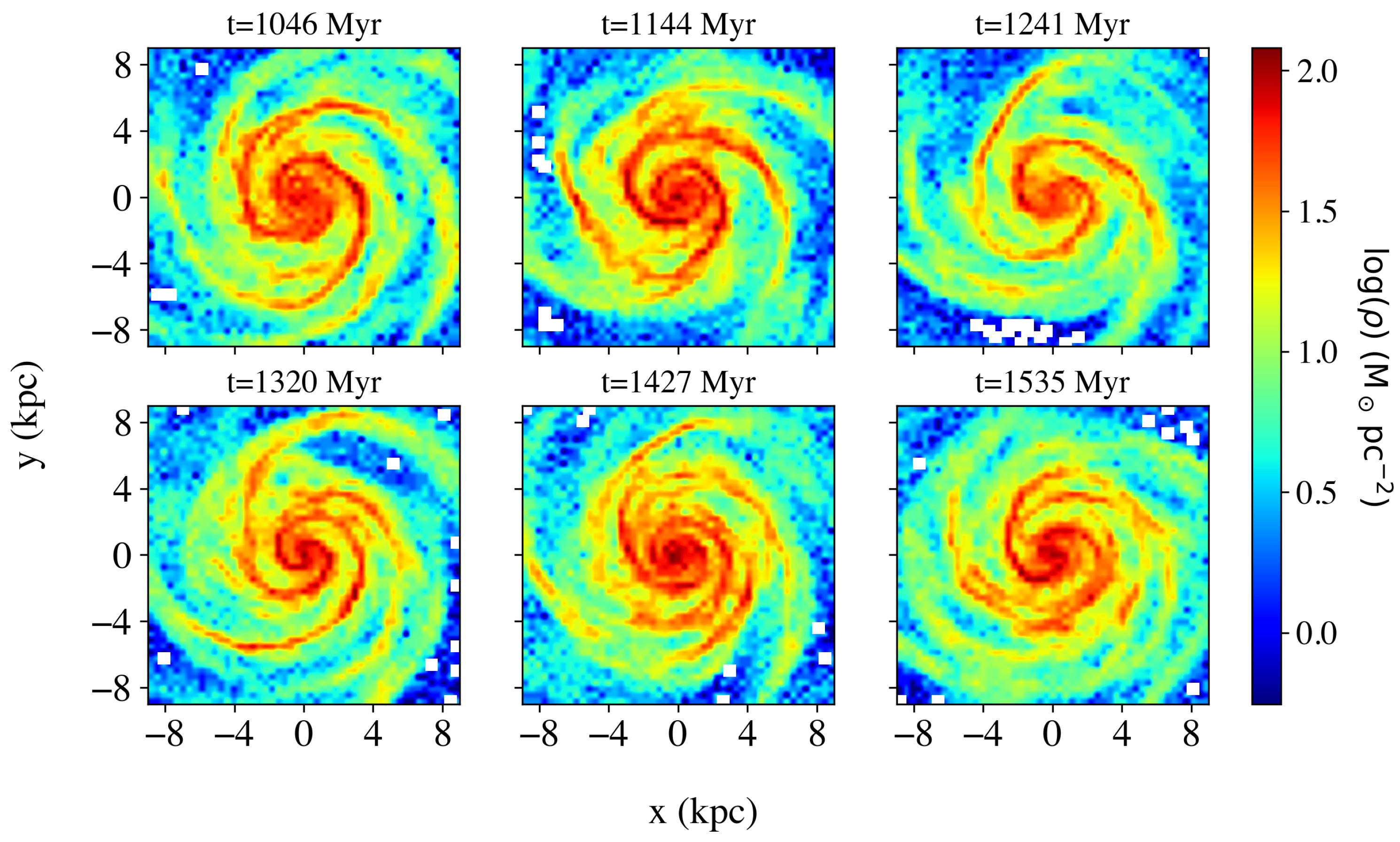

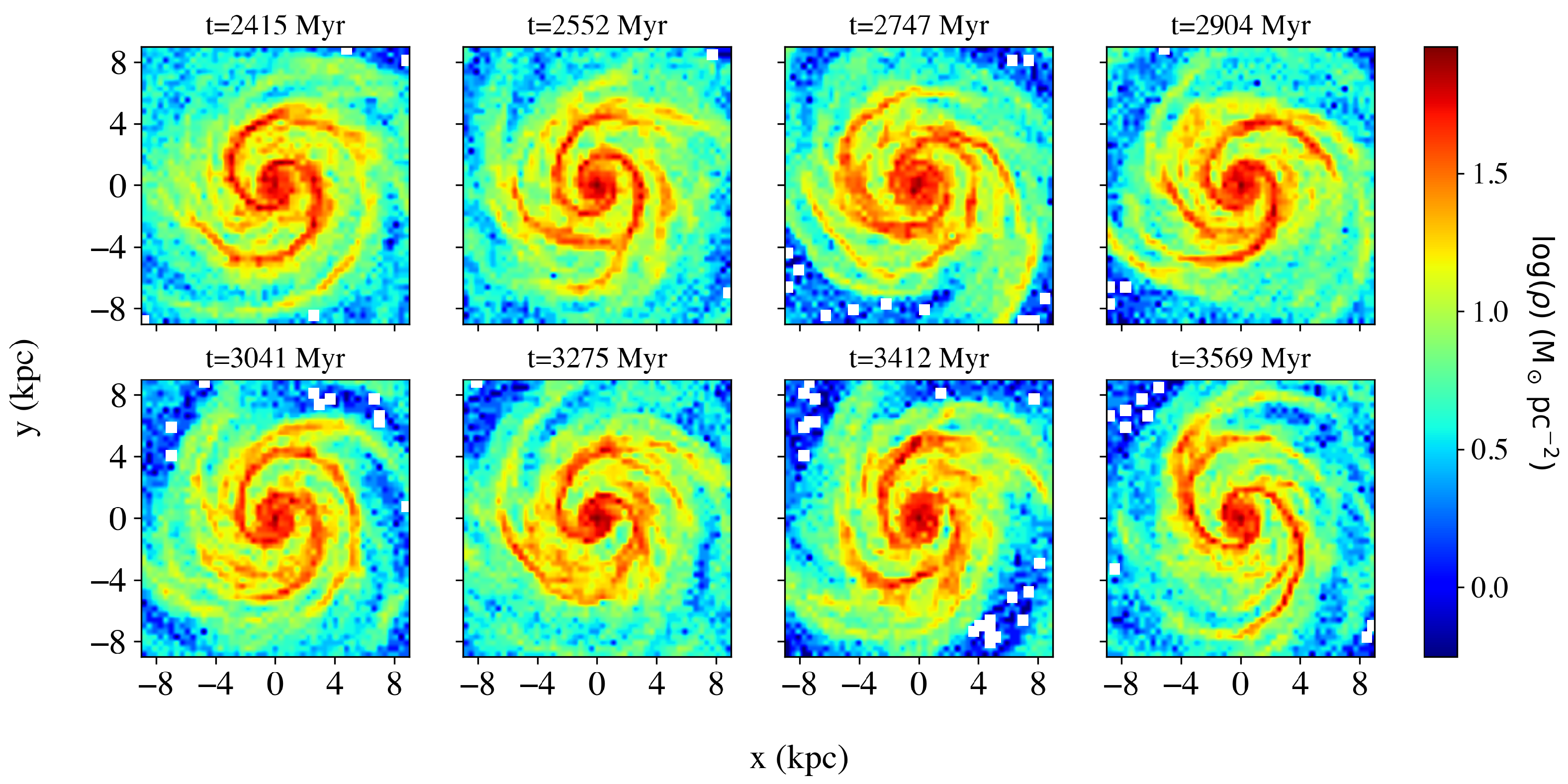

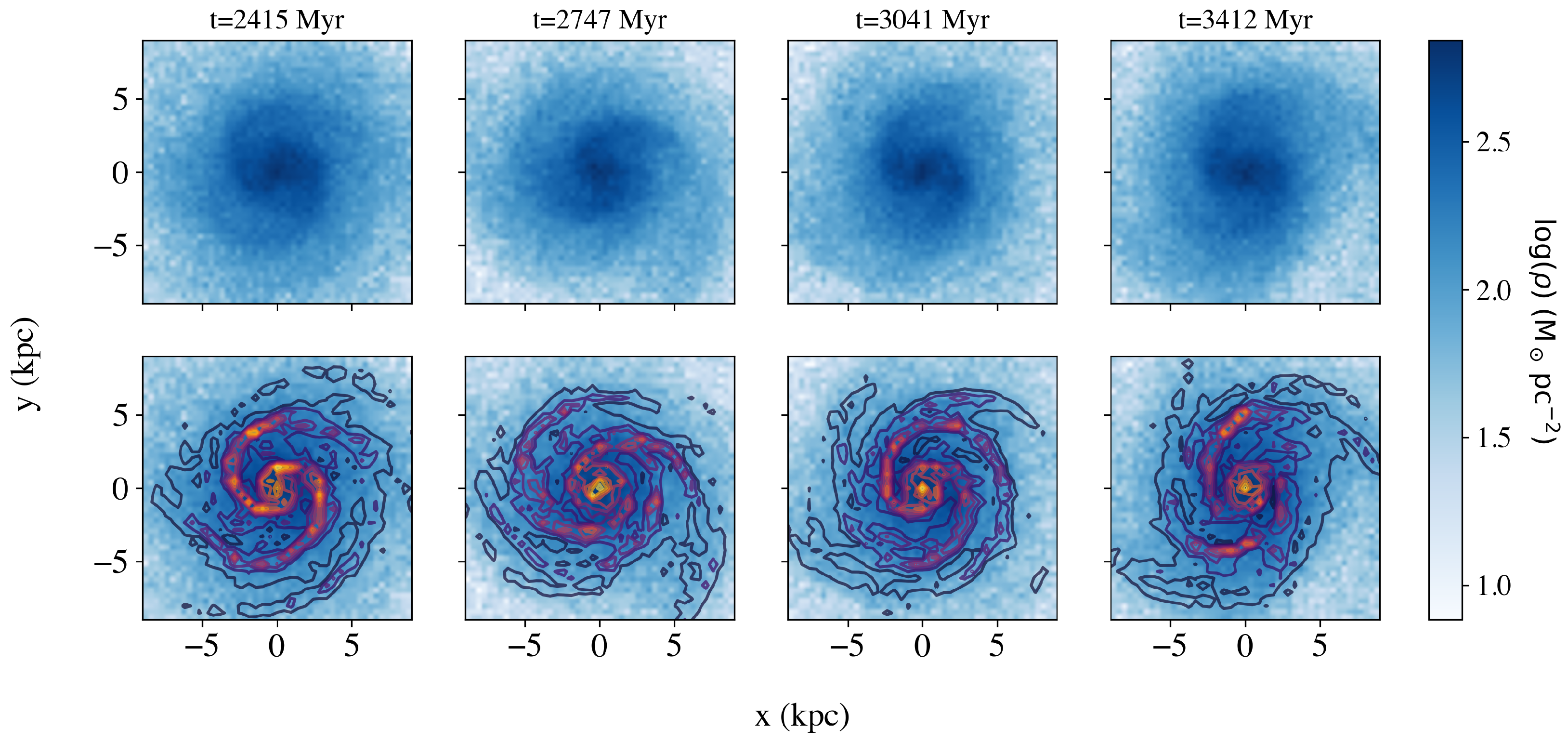

3.1. The Global Morphological Evolution

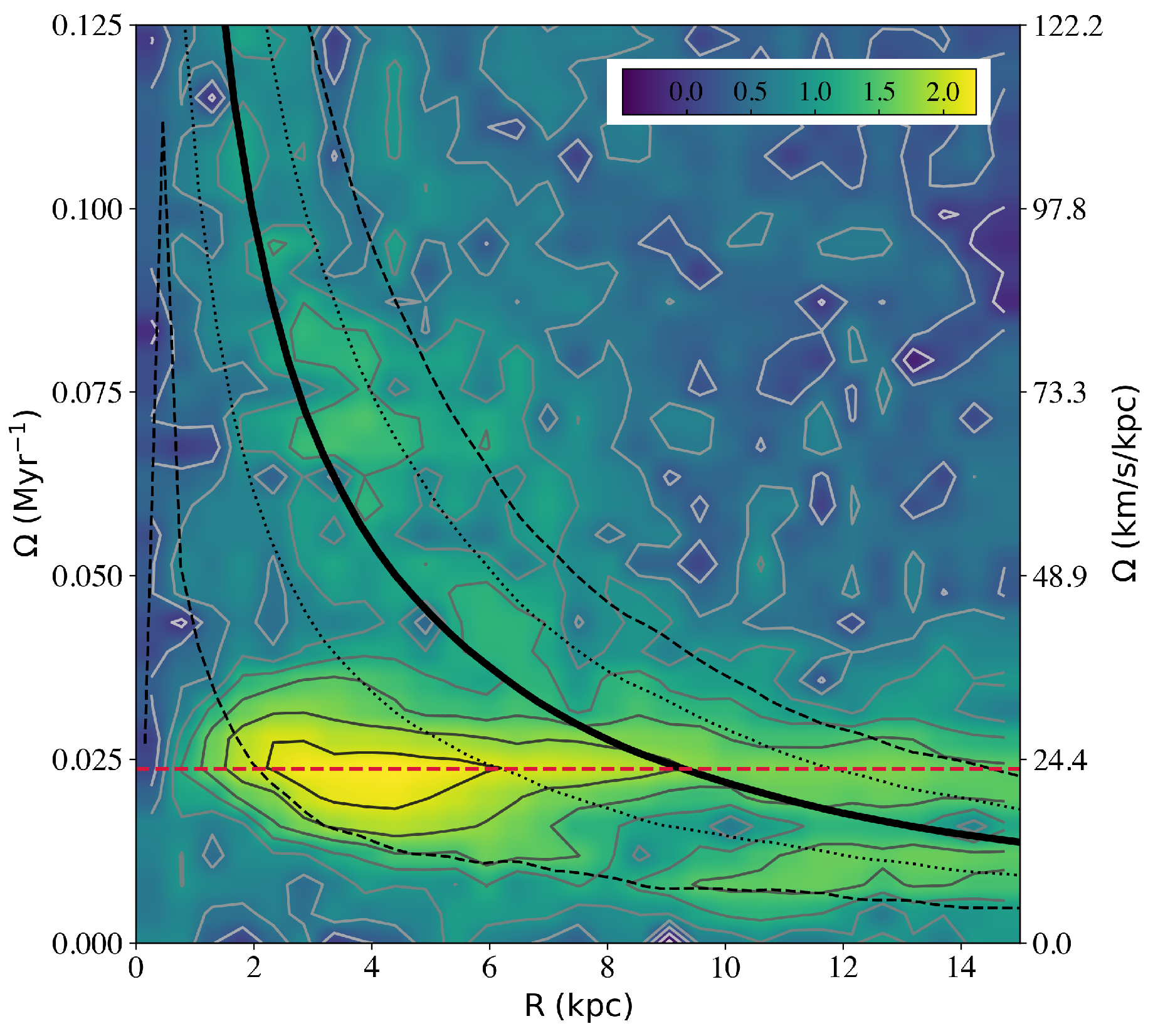

3.2. The Dynamics of Individual Snapshots

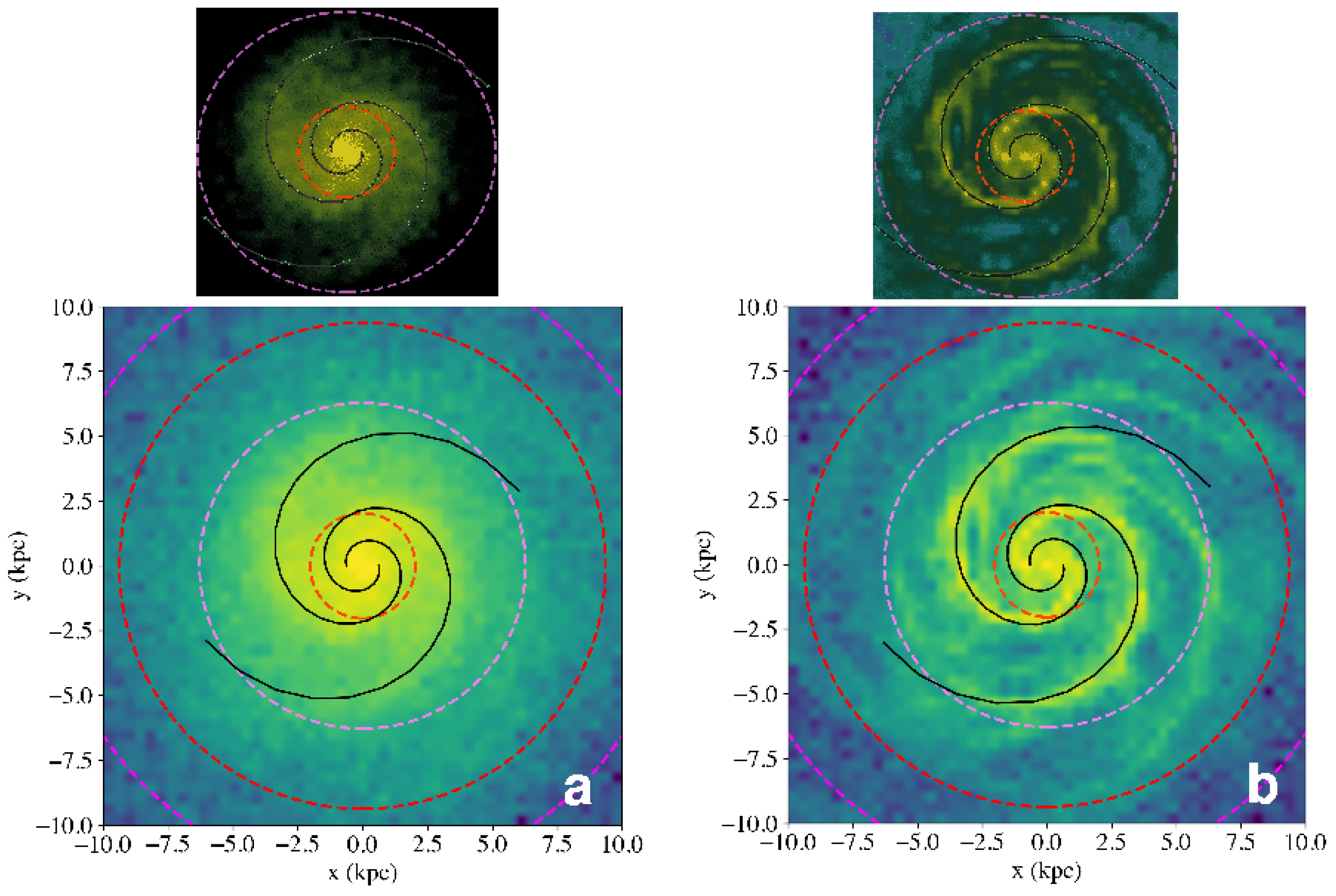

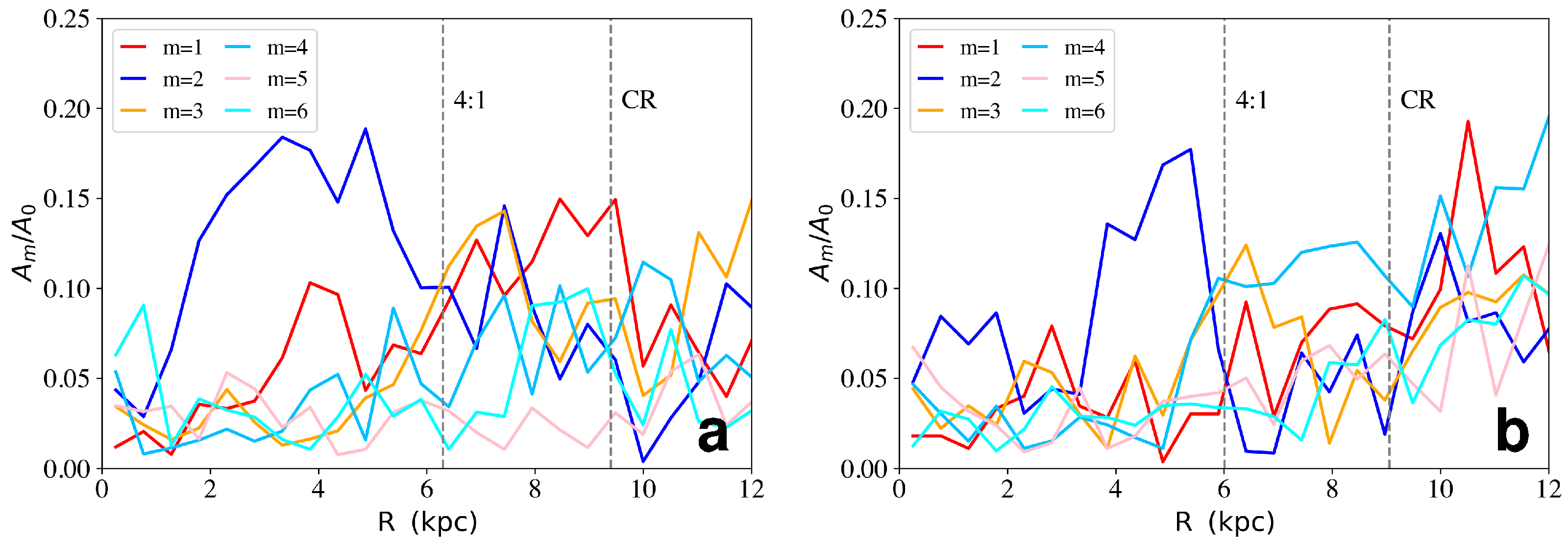

3.3. The Morphology of the Snapshots

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGN | Active Galactic Nuclei |

| ILR | Inner Lindblad Resonance |

| iILR | inner Inner Lindblad Resonance |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| oILR | outer Inner Lindblad Resonance |

| OLR | Outer Lindblad Resonance |

| SFR | Star Formation Rate |

| SPH | Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics |

References

- van Albada, T.S.; Sancisi, R. Dark Matter in Spiral Galaxies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1986, 320, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, A. Dark Matter in Galaxies: Observational overview. In Dark Matter in Galaxies; Ryder, S., Pisano, D., Walker, M., Freeman, K., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 220, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fux, R. 3D self-consistent N-body barred models of the Milky Way. II. Gas dynamics. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 345, 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassoula, E.; Machado, R.E.G.; Rodionov, S.A. Bar formation and evolution in disc galaxies with gas and a triaxial halo: Morphology, bar strength and halo properties. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 429, 1949–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, R.J.J.; Kawata, D.; Cropper, M. Dynamics of stars around spiral arms in an N-body/SPH simulated barred spiral galaxy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 426, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courteau, S.; Rix, H.W. Maximal Disks and the Tully-Fisher Relation. Astrophys. J. 1999, 513, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassoula, E.; Misiriotis, A. Morphology, photometry and kinematics of N-body bars-I. Three models with different halo central concentrations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2002, 330, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Baba, J.; Saitoh, T.R. Interplay between Stellar Spirals and the Interstellar Medium in Galactic Disks. Astrophys. J. 2011, 735, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, R.J.J.; Kawata, D.; Cropper, M. The dynamics of stars around spiral arms. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 421, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Chávez, M.D.; Gómez, G.C.; Puerari, I. Analysis of the spiral structure in a simulated galaxy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 444, 3756–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellwood, J.A.; Carlberg, R.G. Transient Spirals as Superposed Instabilities. Astrophys. J. 2014, 785, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmegreen, D.M.; Elmegreen, B.G.; Dressler, A. Flocculent and grand design spiral arm structure in cluster galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1982, 201, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D.L.; Bertin, G.; Stockton, A.; Grosbol, P.; Moorwood, A.F.M.; Peletier, R.F. 2.1 μm images of the evolved stellar disk and the morphological classification of spiral galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 1994, 288, 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Block, D.L.; Wainscoat, R.J. Morphological differences between optical and infrared images of the spiral galaxy NGC309. Nature 1991, 353, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigar, M.S.; Chorney, N.E.; James, P.A. Near-infrared constraints on the driving mechanisms for spiral structure. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 342, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosbol, P.J.; Patsis, P.A. Stellar disks of optically flocculent and grand design spirals. Decoupling of stellar and gaseous disks. Astron. Astrophys. 1998, 336, 840–854. [Google Scholar]

- Grosbøl, P.; Patsis, P.A.; Pompei, E. Spiral galaxies observed in the near-infrared K band. I. Data analysis and structural parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2004, 423, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, E.E.; González-Lópezlira, R.A. Signatures of Long-lived Spiral Patterns. Astrophys. J. 2013, 765, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, T.; Slyz, A.; Rix, H.W. Probing for Dark Matter within Spiral Galaxy Disks. Astrophys. J. 2001, 562, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, T.; Slyz, A.; Rix, H.W. Dark Matter within High Surface Brightness Spiral Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2003, 586, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsis, P.A.; Kaufmann, D.E. Resonances and the morphology of spirals in N-body simulations. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 352, 469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Contopoulos, G.; Grosbol, P. Stellar dynamics of spiral galaxies: Nonlinear effects at the 4/1 resonance. Astron. Astrophys. 1986, 155, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Contopoulos, G.; Grosbol, P. Stellar dynamics of spiral galaxies: Self-consistent models. Astron. Astrophys. 1988, 197, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Patsis, P.A.; Contopoulos, G.; Grosbol, P. Self-consistent spiral galactic models. Astron. Astrophys. 1991, 243, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Patsis, P.A.; Hiotelis, N.; Contopoulos, G.; Grosbol, P. Hydrodynamic simulations of open normal spiral galaxies: OLR, corotation and 4/1 models. Astron. Astrophys. 1994, 286, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Patsis, P.A.; Grosbol, P.; Hiotelis, N. Interarm features in gaseous models of spiral galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 1997, 323, 762–774. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Velasquez, L.; Patsis, P.A.; Puerari, I.; Moreno, E.; Pichardo, B. Dynamics of Thick, Open Spirals in PERLAS Potentials. Astrophys. J. 2019, 871, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellwood, J.A.; Masters, K.L. Spirals in Galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 60, 73–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellwood, J.A. Spiral Instabilities in N-body Simulations. I. Emergence from Noise. Astrophys. J. 2012, 751, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygnet, J.F.; Tagger, M.; Athanassoula, E.; Pellat, R. Non-linear coupling of spiral modes in disc galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1988, 232, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, G.; Lin, C.C.; Lowe, S.A.; Thurstans, R.P. Modal Approach to the Morphology of Spiral Galaxies. II. Dynamical Mechanisms. Astrophys. J. 1989, 338, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Elmegreen, B. Long-lived Spiral Structure for Galaxies with Intermediate-size Bulges. Astrophys. J. 2016, 826, L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassoula, E.; Romero-Gómez, M.; Masdemont, J.J. Rings, spirals and manifolds. Mem. Soc. Astron. Ital. Suppl. 2011, 18, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.; Hut, P. A hierarchical O(N log N) force-calculation algorithm. Nature 1986, 324, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, C.G.; Dobbs, C.; Pettitt, A.; Konstandin, L. Testing hydrodynamics schemes in galaxy disc simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 4382–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassoula, E.; Bosma, A.; Lambert, J.C.; Makino, J. Performance and accuracy of a GRAPE-3 system for collisionless N-body simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 293, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V. The cosmological simulation code GADGET-2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 364, 1105–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V.; Hernquist, L. Cosmological smoothed particle hydrodynamics simulations: A hybrid multiphase model for star formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 339, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennicutt, R.C., Jr. The Global Schmidt Law in Star-forming Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1998, 498, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernquist, L. N-Body Realizations of Compound Galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 1993, 86, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V.; White, S.D.M. Tidal tails in cold dark matter cosmologies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1999, 307, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V. Modelling star formation and feedback in simulations of interacting galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2000, 312, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V.; Hernquist, L. Formation of a Spiral Galaxy in a Major Merger. Astrophys. J. 2005, 622, L9–L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernquist, L. An Analytical Model for Spherical Galaxies and Bulges. Astrophys. J. 1990, 356, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.J.; Mao, S.; White, S.D.M. The formation of galactic discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 295, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J.J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 1992, 30, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillen, A.C.; Dougherty, J.; Bagley, M.B.; Minchev, I.; Comparetta, J. Structure in phase space associated with spiral and bar density waves in an N-body hybrid galactic disc. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 417, 762–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, R.J.J.; Kawata, D.; Cropper, M. Spiral arm pitch angle and galactic shear rate in N-body simulations of disc galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 553, A77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellwood, J.A.; Athanassoula, E. Unstable modes from galaxy simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1986, 221, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, M.; Hernandez, X.; Yáñez, M.; Moreno, E.; Pichardo, B. A plausible Galactic spiral pattern and its rotation speed. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2004, 350, L47–L51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artymowicz, P.; Lubow, S.H. Dynamics of Ultraharmonic Resonances in Spiral Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1992, 389, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Laughlin, G.; Shu, F.H. Branch, Spur, and Feather Formation in Spiral Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2003, 596, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Villegas, A.; Gómez, G.C.; Pichardo, B. The galactic branches as a possible evidence for transient spiral arms. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 451, 2922–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigar, M.S. Is Messier 74 a barred spiral galaxy?. Near-infrared imaging of M 74. Astron. Astrophys. 2002, 393, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speights, J.C.; Aust, V.; Lu, Q. Spiral Density Waves in the Multiple-armed Galaxy NGC 628. Astrophys. J. 2025, 981, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.T.; Meidt, S.E.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Groves, B.A.; Seibert, M.; Madore, B.F.; Schinnerer, E.; Rich, J.A.; Kobayashi, C.; Kewley, L.J. Azimuthal variations of gas-phase oxygen abundance in NGC 2997. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 618, A64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoperskov, S.A.; Khoperskov, A.V.; Khrykin, I.S.; Korchagin, V.I.; Casetti-Dinescu, D.I.; Girard, T.; van Altena, W.; Maitra, D. Global gravitationally organized spiral waves and the structure of NGC 5247. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 427, 1983–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosbøl, P.; Dottori, H. Star formation in grand-design, spiral galaxies. Young, massive clusters in the near-infrared. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 542, A39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, A.; Gadotti, D.A.; Elmegreen, B.G.; Athanassoula, E.; Elmegreen, D.M.; Bosma, A.; Muñoz-Mateos, J.C. How do spiral arm contrasts relate to bars, disc breaks and other fundamental galaxy properties? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 471, 1070–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patsis, P.A.; Okalidis, P. Normal Spiral Grand-Design Morphologies in Self-Consistent N-Body Models. Galaxies 2025, 13, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060132

Patsis PA, Okalidis P. Normal Spiral Grand-Design Morphologies in Self-Consistent N-Body Models. Galaxies. 2025; 13(6):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060132

Chicago/Turabian StylePatsis, P. A., and P. Okalidis. 2025. "Normal Spiral Grand-Design Morphologies in Self-Consistent N-Body Models" Galaxies 13, no. 6: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060132

APA StylePatsis, P. A., & Okalidis, P. (2025). Normal Spiral Grand-Design Morphologies in Self-Consistent N-Body Models. Galaxies, 13(6), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060132