ASKAP Detection of the Ultra-Long Spin Period Pulsar PSR J0901-4046

Abstract

1. Introduction

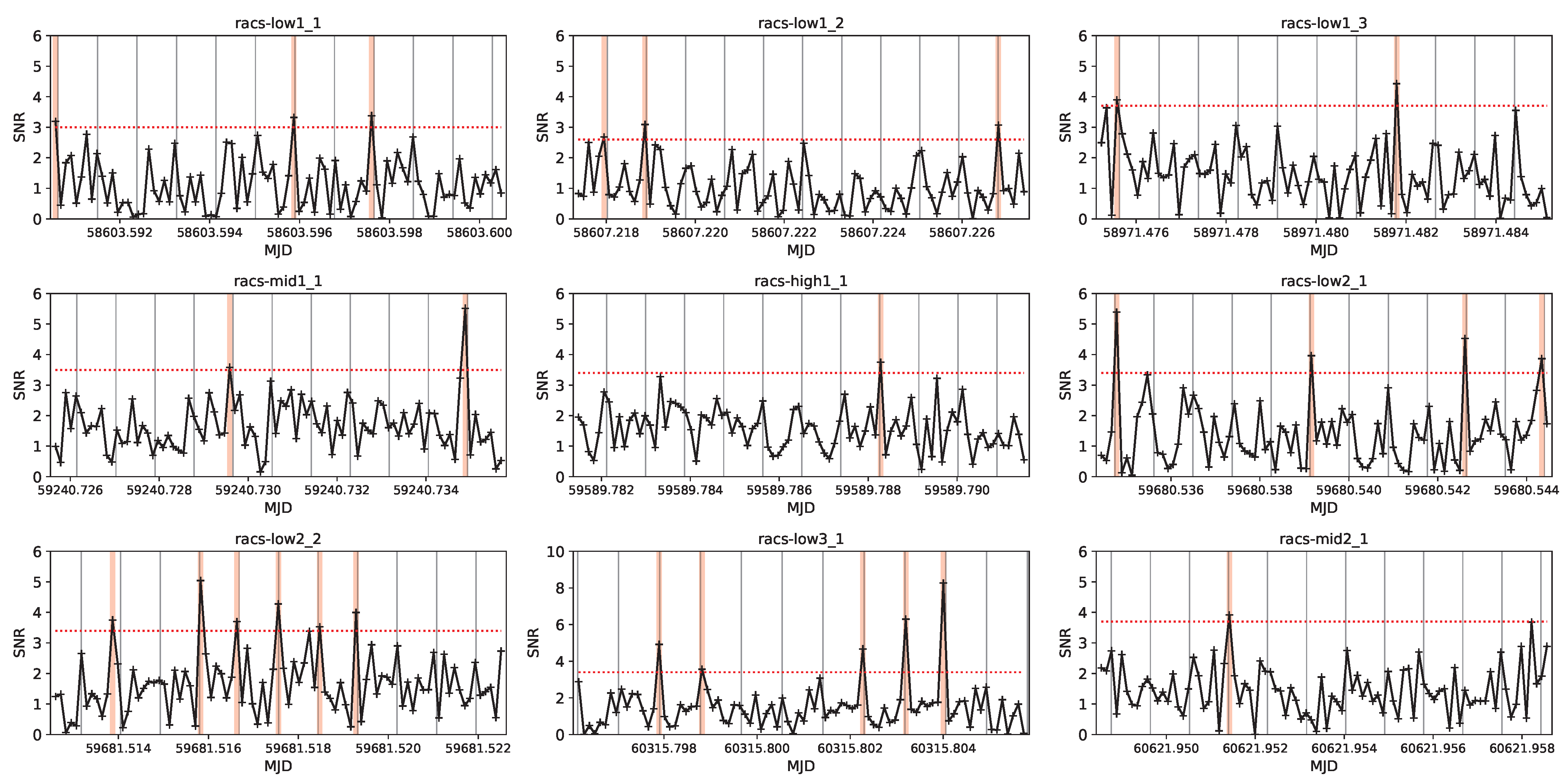

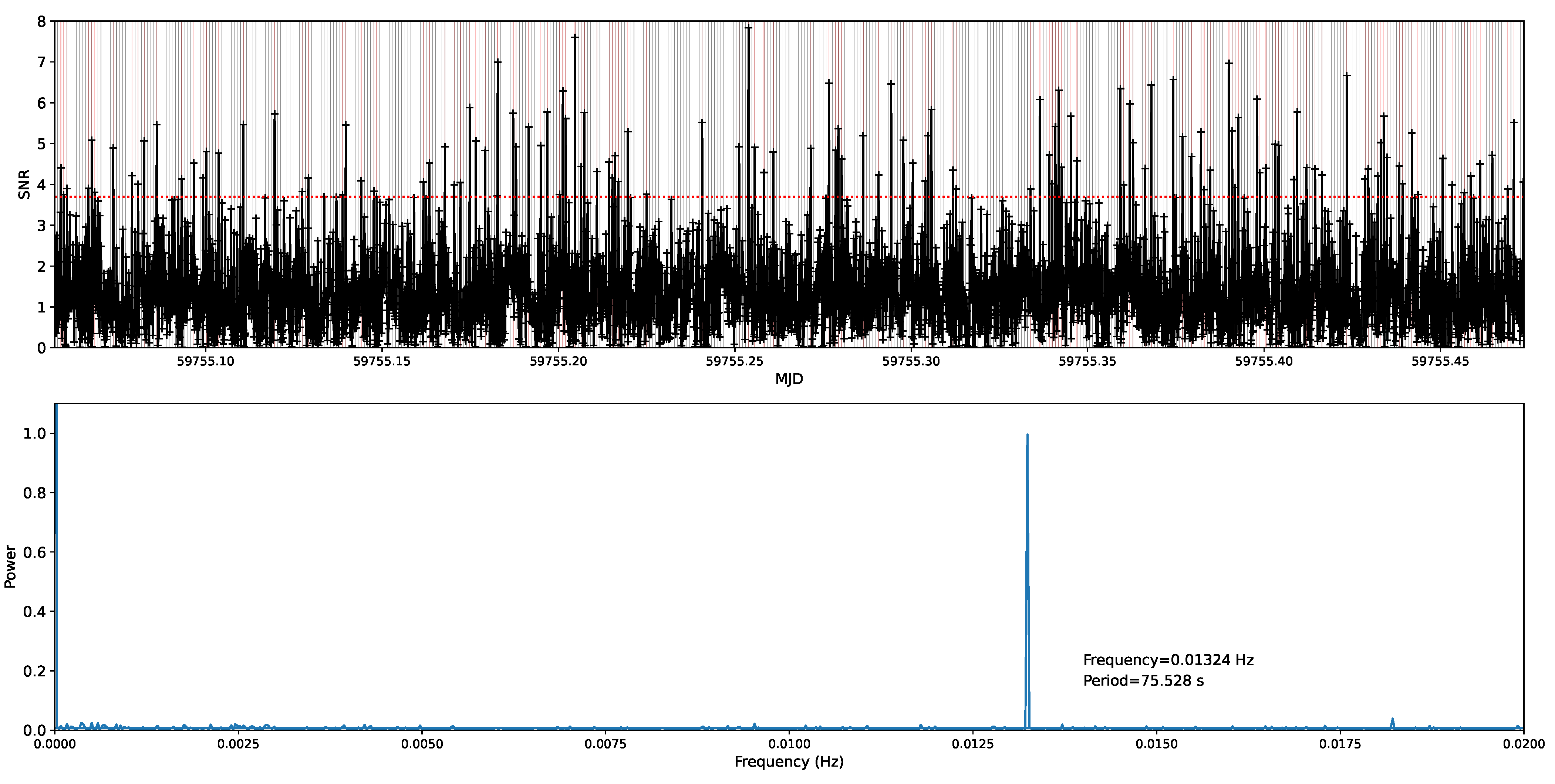

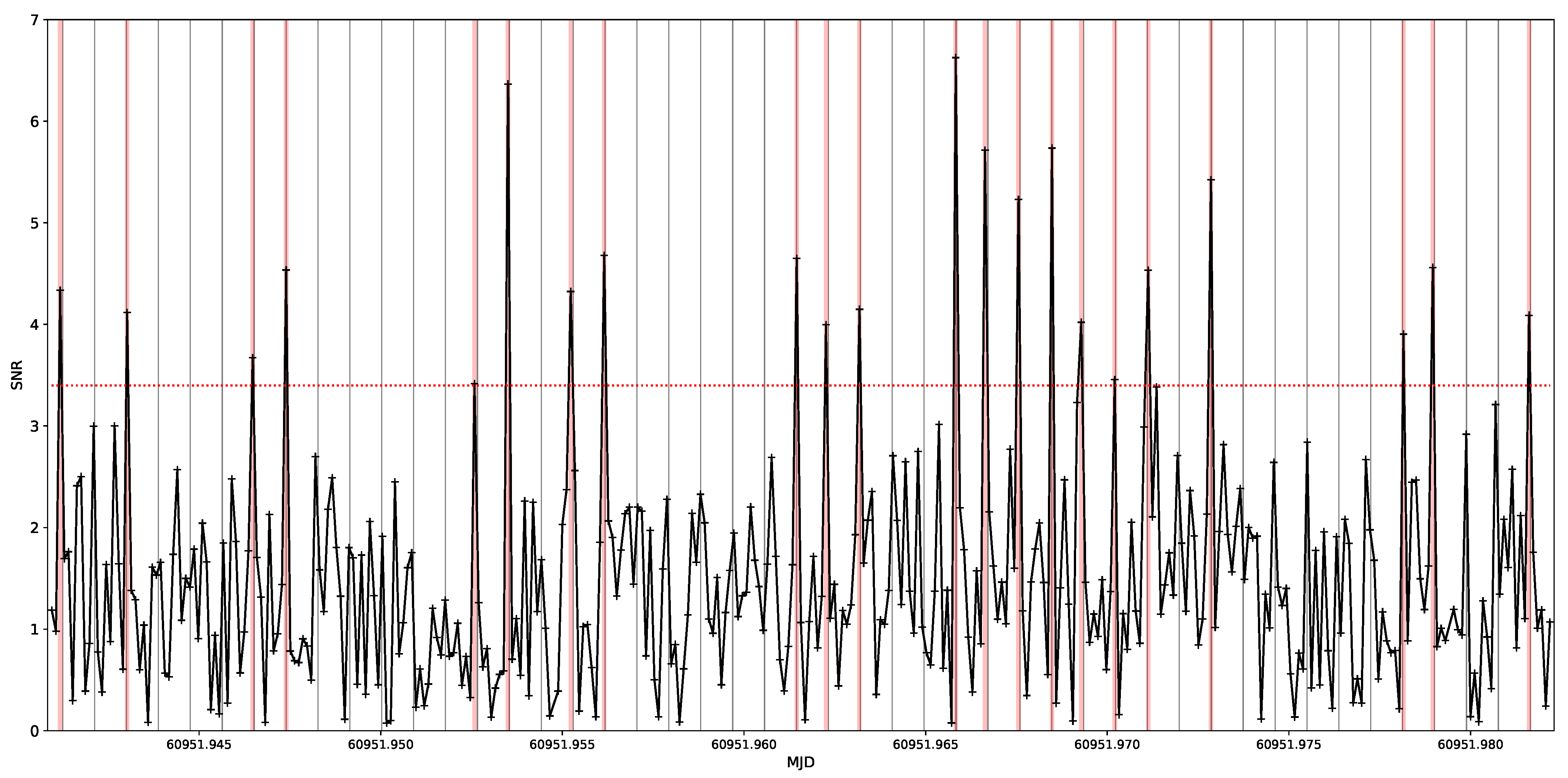

2. The Search for Pulses

2.1. ASKAP Observations

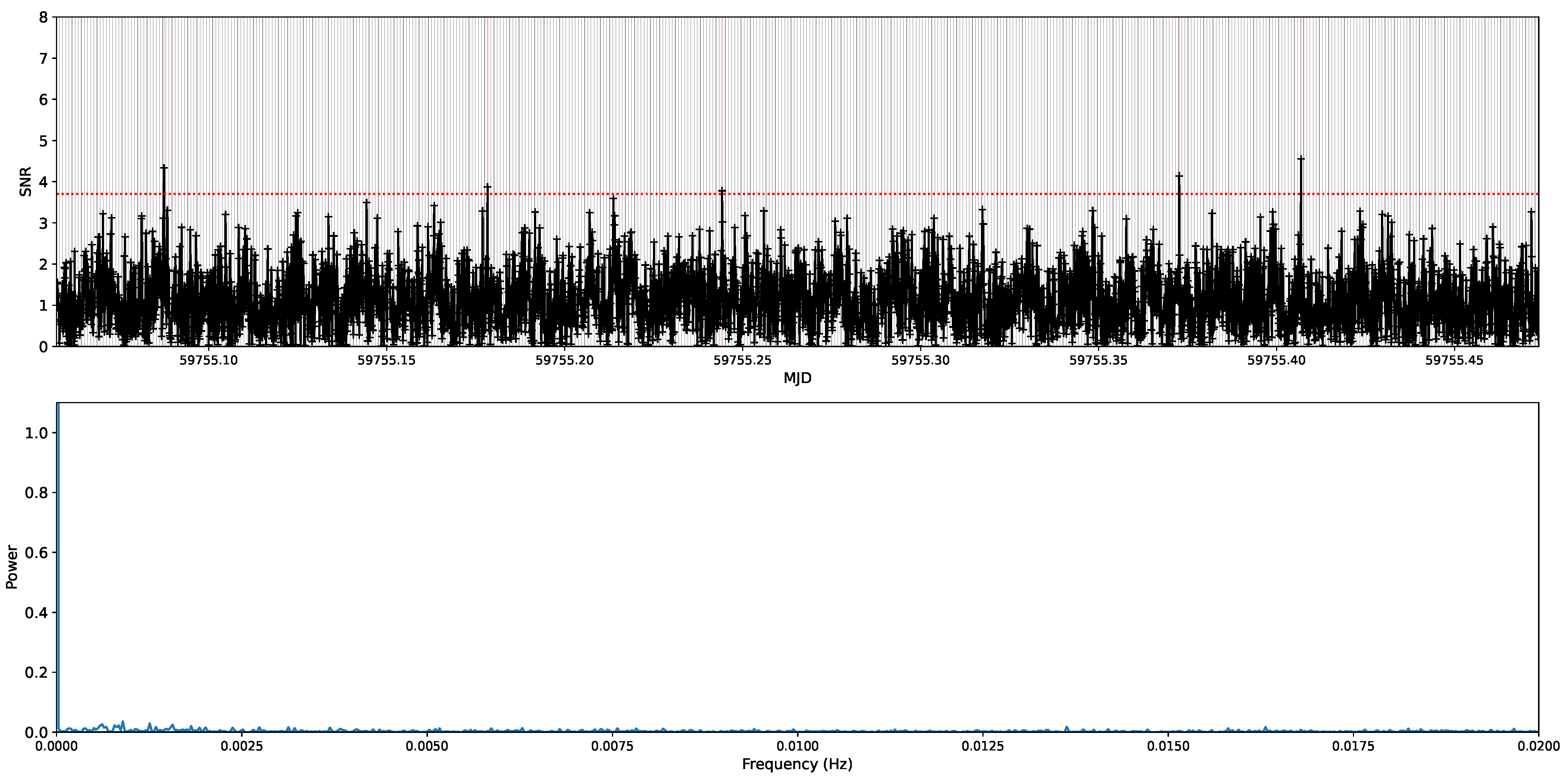

2.2. MWA Observation

3. ASKAP Imaging

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASKAP | Australian SKA Pathfinder |

| CASDA | CSIRO ASKAP Science Data Archive |

| CRACO | (ASKAP) CRAFT Coherent (system) |

| CRAFT | Commensal Realtime ASKAP Fast Transient |

| GMRT | Giant Metre-wave Radio Telescope |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| MeerKAT | Meer Karoo Array Telescope |

| MWA | Murchison Widefield Array |

| RACS | Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey |

| RRAT | Rotating Radio Transient |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| ToO | Target of Opportunity |

| UHF | Ultra-High Frequency |

References

- Caleb, M.; Heywood, I.; Rajwade, K.; Malenta, M.; Willem Stappers, B.; Barr, E.; Chen, W.; Morello, V.; Sanidas, S.; van den Eijnden, J.; et al. Discovery of a radio-emitting neutron star with an ultra-long spin period of 76 s. Nat. Astron. 2022, 6, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, R.N.; Hobbs, G.B.; Teoh, A.; Hobbs, M. The Australia Telescope National Facility Pulsar Catalogue. Astron. J. 2005, 129, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Uttarkar, P.A.; Shannon, R.M.; Lee, Y.W.J.; Dobie, D.; Wang, Z.; Bannister, K.W.; Caleb, M.; Deller, A.T.; Glowacki, M.; et al. The Discovery of a 41 s Radio Pulsar PSR J0311+1402 with ASKAP. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 982, L53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, S.D.; Lazio, T.J.W.; Kassim, N.E.; Ray, P.S.; Markwardt, C.B.; Yusef-Zadeh, F. A powerful bursting radio source towards the Galactic Centre. Nature 2005, 434, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley-Walker, N.; Zhang, X.; Bahramian, A.; McSweeney, S.J.; O’Doherty, T.N.; Hancock, P.J.; Morgan, J.S.; Anderson, G.E.; Heald, G.H.; Galvin, T.J. A radio transient with unusually slow periodic emission. Nature 2022, 601, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleb, M.; Lenc, E.; Kaplan, D.L.; Murphy, T.; Men, Y.P.; Shannon, R.M.; Ferrario, L.; Rajwade, K.M.; Clarke, T.E.; Giacintucci, S.; et al. An emission-state-switching radio transient with a 54-minute period. Nat. Astron. 2024, 8, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.J.; Caleb, M.; Murphy, T.; Lenc, E.; Kaplan, D.L.; Ferrario, L.; Wadiasingh, Z.; Anumarlapudi, A.; Hurley-Walker, N.; Karambelkar, V.; et al. The emission of interpulses by a 6.45-h-period coherent radio transient. Nat. Astron. 2025, 9, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Rea, N.; Bao, T.; Kaplan, D.L.; Lenc, E.; Wadiasingh, Z.; Hare, J.; Zic, A.; Anumarlapudi, A.; Bera, A.; et al. Detection of X-ray emission from a bright long-period radio transient. Nature 2025, 642, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.A.; Clarke, T.E.; Curtin, A.; Kumar, A.; Mckinven, R.; Shin, K.; Stairs, I.; Brar, C.; Burdge, K.; Chatterjee, S.; et al. CHIME/Fast Radio Burst/Pulsar Discovery of a Nearby Long-period Radio Transient with a Timing Glitch. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 990, L49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, M.; Rea, N.; Graber, V.; Hurley-Walker, N. Long-period Pulsars as Possible Outcomes of Supernova Fallback Accretion. Astrophys. J. 2022, 934, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençali, A.A.; Ertan, Ü.; Alpar, M.A. Evolution of the long-period pulsar PSR J0901-4046. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2023, 520, L11–L15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, S. Enigma of GLEAM-X J162759.5–523504.3. J. Astrophys. Astron. 2023, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, M.C.; Bhat, N.D.R.; Caleb, M.; Driessen, L.N.; Jankowski, F.; Kramer, M.; Morello, V.; Pastor-Marazuela, I.; Rajwade, K.; Roy, J.; et al. Slow and steady: Long-term evolution of the 76-s pulsar J0901-4046. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 540, 2131–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotan, A.W.; Bunton, J.D.; Chippendale, A.P.; Whiting, M.; Tuthill, J.; Moss, V.A.; McConnell, D.; Amy, S.W.; Huynh, M.T.; Allison, J.R.; et al. Australian square kilometre array pathfinder: I. system description. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2021, 38, e009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, D.; Hale, C.L.; Lenc, E.; Banfield, J.K.; Heald, G.; Hotan, A.W.; Leung, J.K.; Moss, V.A.; Murphy, T.; O’Brien, A.; et al. The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey I: Design and first results. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2020, 37, e048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C.L.; McConnell, D.; Thomson, A.J.M.; Lenc, E.; Heald, G.H.; Hotan, A.W.; Leung, J.K.; Moss, V.A.; Murphy, T.; Pritchard, J.; et al. The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey Paper II: First Stokes I Source Catalogue Data Release. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2021, 38, e058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.W.; Thomson, A.J.M.; Pritchard, J.; Lenc, E.; Moss, V.A.; McConnell, D.; Wieringa, M.H.; Whiting, M.T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey IV: Continuum imaging at 1367.5 MHz and the first data release of RACS-mid. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2023, 40, e034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.W.; Grundy, J.A.; Heald, G.H.; Lenc, E.; Leung, J.K.; McConnell, D.; Murphy, T.; Pritchard, J.; Rose, K.; Thomson, A.J.M.; et al. The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey V: Cataloguing the sky at 1 367.5 MHz and the second data release of RACS-mid. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2024, 41, e003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Ross, K.; Thomson, A.J.M.; Lenc, E.; Murphy, T.; Galvin, T.J.; Hotan, A.W.; Moss, V.A.; Whiting, M.T. The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS) VI: The RACS-high 1655.5 MHz images and catalogue. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2025, 42, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, G.B.; Edwards, R.T.; Manchester, R.N. TEMPO2, a new pulsar-timing package—I. An overview. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 369, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingay, S.J.; Goeke, R.; Bowman, J.D.; Emrich, D.; Ord, S.M.; Mitchell, D.A.; Morales, M.F.; Booler, T.; Crosse, B.; Wayth, R.B.; et al. The Murchison Widefield Array: The Square Kilometre Array Precursor at Low Radio Frequencies. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2013, 30, e007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayth, R.B.; Tingay, S.J.; Trott, C.M.; Emrich, D.; Johnston-Hollitt, M.; McKinley, B.; Gaensler, B.M.; Beardsley, A.P.; Booler, T.; Crosse, B.; et al. The Phase II Murchison Widefield Array: Design overview. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2018, 35, e033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingay, S.J. The Murchison Widefield Array Enters Adolescence: A Personal Review of the Early Years of Operations. Galaxies 2025, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bannister, K.W.; Gupta, V.; Deng, X.; Pilawa, M.; Tuthill, J.; Bunton, J.D.; Flynn, C.; Glowacki, M.; Jaini, A.; et al. The CRAFT coherent (CRACO) upgrade I: System description and results of the 110-ms radio transient pilot survey. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2025, 42, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, M.; Dempsey, J.; Whiting, M.T.; Ophel, M. The CSIRO ASKAP Science Data Archive. In Proceedings of the Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XXVII; Ballester, P., Ibsen, J., Solar, M., Shortridge, K., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series; Astronomical Society of the Pacific: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 522, p. 263. [Google Scholar]

| Survey | SBID | Field | Beam | Offset | Date | Start Time | Frequency Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (deg) | (yyyy-mm-dd) | (UT) | (MHz) | ||||

| RACS-low1_1 | 8598 | RACS_0911-37A | 30 | 0.62 | 2019-04-30 | 14:06:59.7 | 743.491–1031.491 |

| RACS-low1_2 | 8641 | RACS_0855-43A | 20 | 0.69 | 2019-05-04 | 05:09:51.4 | 743.491–1031.491 |

| RACS-low1_3 | 13739 | RACS_0855-43A | 20 | 0.69 | 2020-05-02 | 11:21:04.8 | 743.491–1031.491 |

| RACS-mid1_1 | 22042 | RACS_0859-41 | 27 | 0.08 | 2021-01-26 | 17:19:37.7 | 1151.491–1439.491 a |

| RACS-high1_1 | 35676 | RACS_0859-41 | 27 | 0.08 | 2022-01-10 | 18:40:51.7 | 1511.491–1799.491 |

| RACS-low2_1 | 39244 | RACS_0911-37 | 30 | 0.62 | 2022-04-11 | 12:44:53.6 | 743.491–1031.491 |

| RACS-low2_2 | 39310 | RACS_0855-43 | 19 | 0.72 | 2022-04-12 | 12:13:30.8 | 743.491–1031.491 |

| Test_0900-40 | 41912 | TEST_0900-40 | 9 | 0.56 | 2022-06-25 | 01:23:34.4 | 799.491–1087.491 |

| RACS-low3_1 | 56856 | RACS_0859-41 | 27 | 0.08 | 2024-01-06 | 19:02:18.8 | 799.491–1087.491 |

| RACS-mid2_1 | 67689 | RACS_0859-41 | 27 | 0.08 | 2024-11-10 | 22:46:28.6 | 1151.491–1439.491 a |

| ToO | 77422 | PSR_J0901-4046 | 15 | 0.00 | 2025-10-03 | 22:37:51.6 | 799.491–1087.491 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lenc, E.; Edwards, P.G.; Sett, S.; Caleb, M. ASKAP Detection of the Ultra-Long Spin Period Pulsar PSR J0901-4046. Galaxies 2025, 13, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060131

Lenc E, Edwards PG, Sett S, Caleb M. ASKAP Detection of the Ultra-Long Spin Period Pulsar PSR J0901-4046. Galaxies. 2025; 13(6):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060131

Chicago/Turabian StyleLenc, Emil, Philip G. Edwards, Susmita Sett, and Manisha Caleb. 2025. "ASKAP Detection of the Ultra-Long Spin Period Pulsar PSR J0901-4046" Galaxies 13, no. 6: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060131

APA StyleLenc, E., Edwards, P. G., Sett, S., & Caleb, M. (2025). ASKAP Detection of the Ultra-Long Spin Period Pulsar PSR J0901-4046. Galaxies, 13(6), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060131