Emerging Molecular and Computational Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma: Innovations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Synthesis of the Evidence

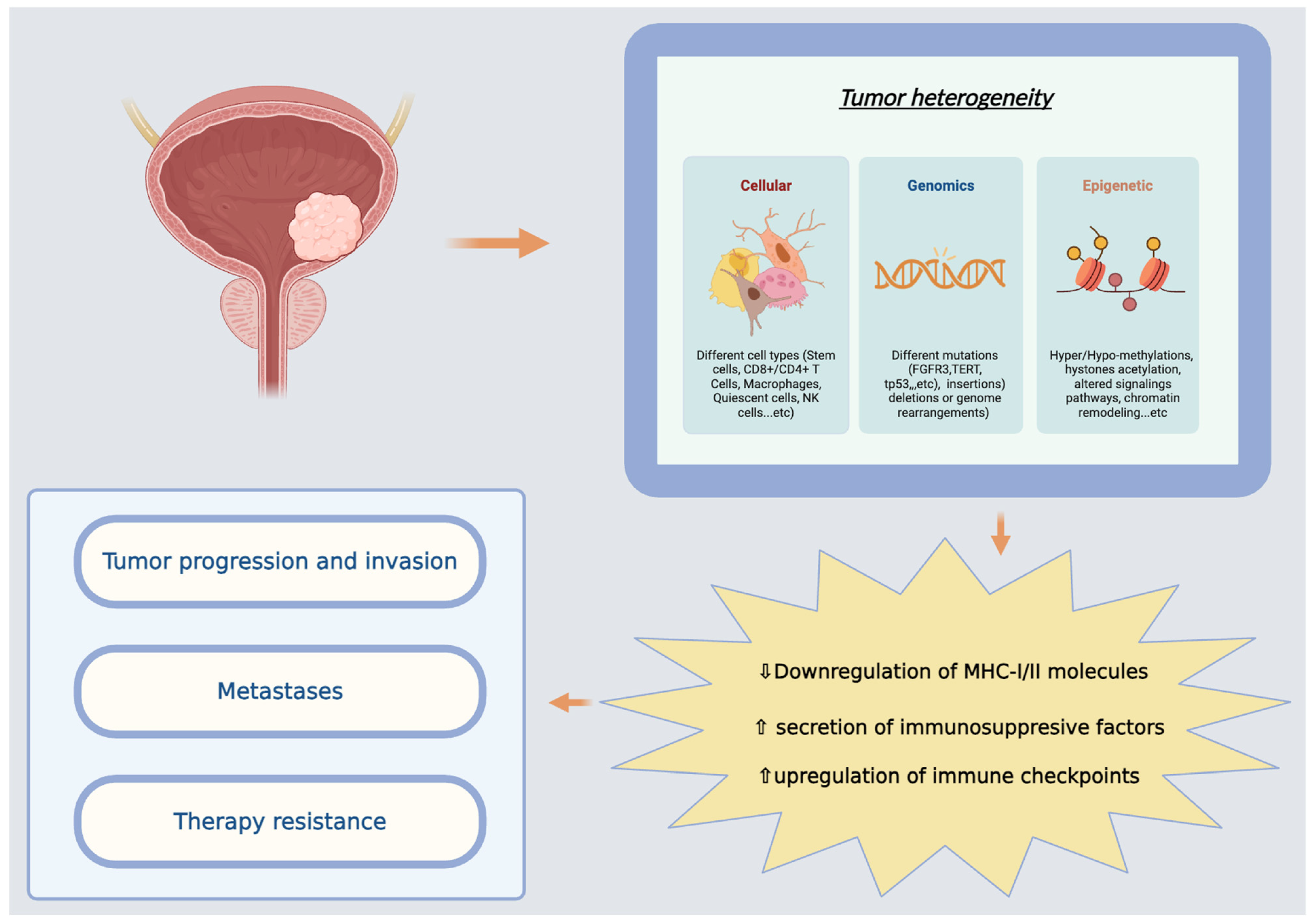

3.1. Molecular Subtyping (Taxonomic Groups)

3.2. Pathway-Specific Molecular Alterations

3.2.1. Cell Signaling and Gene Regulation

3.2.2. Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Immune Modulation

3.2.3. Immune Profile and Targeted Therapies

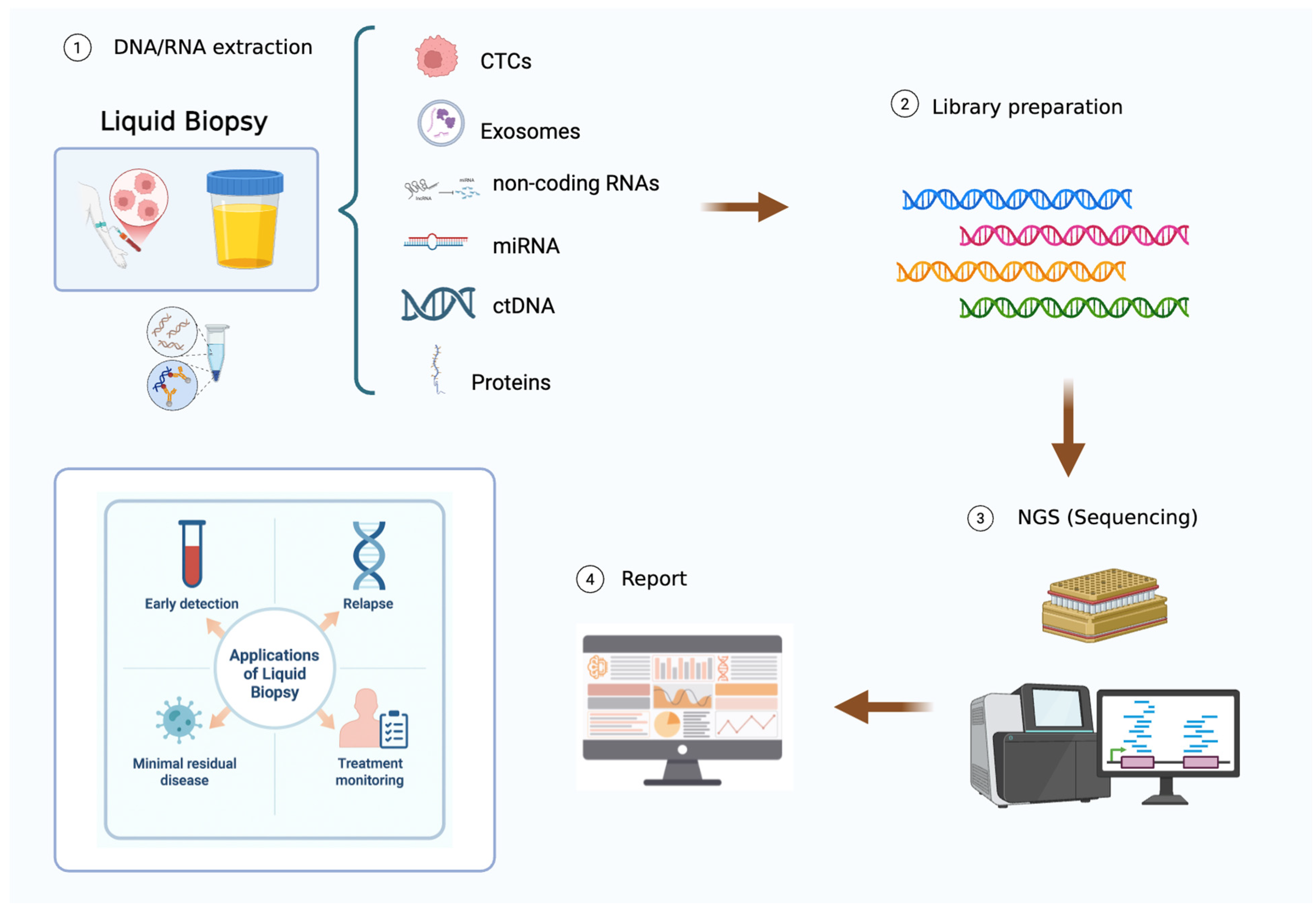

3.3. Liquid Biopsy

New Perspectives About ctDNA

3.4. Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

4. Future Directions

4.1. Emerging-Directed Therapies

4.2. AI Application in BC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Witjes, J.A.; Bruins, H.M.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; Gakis, G.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; Lorch, A.; Neuzillet, Y.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2020 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger-Christ, K.M.; Mourtzinos, A.; Lee, P.J.; Zagha, R.M.; Cain, J.; Silverman, M.; Libertino, J.A.; Summerhayes, I.C. Identification of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations in urine sediment DNA samples complements cytology in bladder tumor detection. Cancer 2003, 98, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rhijn, B.W.G.; Van Der Kwast, T.H.; Vis, A.N.; Kirkels, W.J.; Boevé, E.R.; Jöbsis, A.C.; Zwarthoff, E.C. FGFR3 and P53 Characterize Alternative Genetic Pathways in the Pathogenesis of Urothelial Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 1911–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkar, A.A.; Wallerand, H.; Radvanyi, F.; Lahaye, J.-B.; Pissard, S.; Lecerf, L.; Kouyoumdjian, J.C.; Abbou, C.C.; Pairon, J.-C.; Jaurand, M.-C.; et al. FGFR3 and TP53 gene mutations define two distinct pathways in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8108–8112. [Google Scholar]

- Orlow, I.; LaRue, H.; Osman, I.; Lacombe, L.; Moore, L.; Rabbani, F.; Meyer, F.; Fradet, Y.; Cordon-Cardo, C. Deletions of the INK4A Gene in Superficial Bladder Tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.P.; Datar, R.H.; Cote, R.J. Molecular Pathways in Invasive Bladder Cancer: New Insights Into Mechanisms, Progression, and Target Identification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5552–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-R. Urothelial tumorigenesis: A tale of divergent pathways. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.G.; Kim, J.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Bellmunt, J.; Guo, G.; Cherniack, A.D.; Hinoue, T.; Laird, P.W.; Hoadley, K.A.; Akbani, R.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell 2017, 171, 540–556.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenov, Y.; Brocks, D.; Gerhäuser, C. Intratumor heterogeneity in epigenetic patterns. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 51, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, M.H.Y.; Feng, M.; McConkey, D.J.; Choi, W. Update on bladder cancer molecular subtypes. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 2881–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Porten, S.; Kim, S.; Willis, D.; Plimack, E.R.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Roth, B.; Cheng, T.; Tran, M.; Lee, I.-L.; et al. Identification of Distinct Basal and Luminal Subtypes of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer with Different Sensitivities to Frontline Chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamoun, A.; De Reyniès, A.; Allory, Y.; Sjödahl, G.; Robertson, A.G.; Seiler, R.; Hoadley, K.A.; Groeneveld, C.S.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Choi, W.; et al. A Consensus Molecular Classification of Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindskrog, S.V.; Prip, F.; Lamy, P.; Taber, A.; Groeneveld, C.S.; Birkenkamp-Demtröder, K.; Jensen, J.B.; Strandgaard, T.; Nordentoft, I.; Christensen, E.; et al. An integrated multi-omics analysis identifies prognostic molecular subtypes of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbadilla, T.C.; Pérez, M.Á.; Cuadra, J.D.P.; De Vera, M.T.D.; Arco, F.A.; Muñoz, I.G.; De La Blanca, R.S.-P.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Matas-Rico, E.; Martín, M.I.H. The Role of Immunohistochemistry as a Surrogate Marker in Molecular Subtyping and Classification of Bladder Cancer. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.T.; Pham, Q.T.; Nguyen, N.M.T.; Nguyen, P.N.; Bui, T.T.T.; Ngo, Q.D. Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Basal and Luminal Markers in Bladder Cancer: A Study from a Single Institution. Life 2024, 14, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Ochoa, A.; McConkey, D.J.; Aine, M.; Höglund, M.; Kim, W.Y.; Real, F.X.; Kiltie, A.E.; Milsom, I.; Dyrskjøt, L.; et al. Genetic Alterations in the Molecular Subtypes of Bladder Cancer: Illustration in the Cancer Genome Atlas Dataset. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.P.; Birkhahn, M.; Cote, R.J. p53 and retinoblastoma pathways in bladder cancer. World J. Urol. 2007, 25, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouissou, S.; Bernard-Pierrot, I.; De Reyniès, A.; Lepage, M.-L.; Krucker, C.; Chapeaublanc, E.; Hérault, A.; Kamoun, A.; Caillault, A.; Letouzé, E.; et al. EGFR as a potential therapeutic target for a subset of muscle-invasive bladder cancers presenting a basal-like phenotype. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 244ra91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsman, M.R.; Overgaard, J. The impact of hypoxia and its modification of the outcome of radiotherapy. J. Radiat. Res. 2016, 57, i90–i98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwiatkowski, D.; McConkey, D.J.; Meeks, J.J.; Freeman, S.S.; Bellmunt, J.; Getz, G.; Lerner, S.P. The Cancer Genome Atlas Expression Subtypes Stratify Response to Checkpoint Inhibition in Advanced Urothelial Cancer and Identify a Subset of Patients with High Survival Probability. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, W.M.; Lerner, S.P.; Groshen, S.; Stein, J.P.; Shi, S.-R.; Raghavan, D.; Esrig, D.; Steinberg, G.; Wood, D.; Klotz, L.; et al. Phase III Study of Molecularly Targeted Adjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Urothelial Cancer of the Bladder Based on p53 Status. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3443–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.P.; Castelao, J.E.; Hawes, D.; Tsao-Wei, D.D.; Jiang, X.; Shi, S.-R.; Datar, R.H.; Skinner, E.C.; Stein, J.P.; Groshen, S.; et al. Combination of molecular alterations and smoking intensity predicts bladder cancer outcome: A report from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program. Cancer 2013, 119, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, R.; Struckmann, K.; Schraml, P.; Wagner, U.; Forster, T.; Moch, H.; Fijan, A.; Bruderer, J.; Wilber, K.; Mihatsch, M.J.; et al. Amplification pattern of 12q13-q15 genes (MDM2, CDK4, GLI) in urinary bladder cancer. Oncogene 2002, 21, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.A.; Ganesan, R.; Hiller, L.; Cooke, P.W.; Murray, P.; Young, L.S.; James, N.D. BCL2 expression predicts survival in patients receiving synchronous chemoradiotherapy in advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Oncol. Rep. 2003, 10, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korkolopoulou, P.; Lazaris, A.C.; Konstantinidou, A.-E.; Kavantzas, N.; Patsouris, E.; Christodoulou, P.; Thomas-Tsagli, E.; Davaris, P. Differential Expression of bcl-2 Family Proteins in Bladder Carcinomas. Eur. Urol. 2002, 41, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rhijn, B.W.G.; Zuiverloon, T.C.M.; Vis, A.N.; Radvanyi, F.; Van Leenders, G.J.L.H.; Ooms, B.C.M.; Kirkels, W.J.; Lockwood, G.A.; Boevé, E.R.; Jöbsis, A.C.; et al. Molecular Grade (FGFR3/MIB-1) and EORTC Risk Scores Are Predictive in Primary Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2010, 58, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkhahn, M.; Mitra, A.P.; Williams, A.J.; Lam, G.; Ye, W.; Datar, R.H.; Balic, M.; Groshen, S.; Steven, K.E.; Cote, R.J. Predicting Recurrence and Progression of Noninvasive Papillary Bladder Cancer at Initial Presentation Based on Quantitative Gene Expression Profiles. Eur. Urol. 2010, 57, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.P.; Lam, L.L.; Ghadessi, M.; Erho, N.; Vergara, I.A.; Alshalalfa, M.; Buerki, C.; Haddad, Z.; Sierocinski, T.; Triche, T.J.; et al. Discovery and Validation of Novel Expression Signature for Postcystectomy Recurrence in High-Risk Bladder Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, H.; Inoue, S.; Miyamoto, H. Histopathological and prognostic significance of the expression of sex hormone receptors in bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of immunohistochemical studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q. Trop2 expression contributes to tumor pathogenesis by activating the ERK MAPK pathway. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Trepka, K.; Sjöström, M.; Egusa, E.A.; Chu, C.E.; Zhu, J.; Chan, E.; Gibb, E.A.; Badura, M.L.; Contreras-Sanz, A.; et al. TROP2 Expression Across Molecular Subtypes of Urothelial Carcinoma and Enfortumab Vedotin-resistant Cells. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, F.; Vakar-Lopez, F.; Roudier, M.P.; Garcia, J.; Arora, S.; Cheng, H.H.; Schweizer, M.T.; Haffner, M.C.; Lee, J.K.; Yu, E.Y.; et al. Metastatic Bladder Cancer Expression and Subcellular Localization of Nectin-4 and Trop-2 in Variant Histology: A Rapid Autopsy Study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2023, 21, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.-H.; Crist, S.A.; Zhang, G.-J.; Iwamoto, Y.; See, W.A. Interleukin-6 production by human bladder tumor cell lines is up-regulated by bacillus Calmette-Guérin through nuclear factor-kappaB and Ap-1 via an immediate early pathway. J. Urol. 2002, 168, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishioka, J.; Saito, K.; Sakura, M.; Yokoyama, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Numao, N.; Koga, F.; Masuda, H.; Fujii, Y.; Kawakami, S.; et al. Development of a nomogram incorporating serum C-reactive protein level to predict overall survival of patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma and its evaluation by decision curve analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, B.; Shariat, S.F.; Kim, J.-H.; Wheeler, T.M.; Slawin, K.M.; Lerner, S.P. Preoperative plasma levels of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor predict disease recurrence and survival of patients with bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2002, 167, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, L.M.; Salinas, V.H.; Brown, K.E.; Vanguri, V.K.; Freeman, G.J.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Sharpe, A.H. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 3015–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnath, S.; Mangus, C.W.; Wang, J.C.M.; Wei, F.; He, A.; Kapoor, V.; Foley, J.E.; Massey, P.R.; Felizardo, T.C.; Riley, J.L.; et al. The PDL1-PD1 Axis Converts Human TH 1 Cells into Regulatory T Cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 111ra120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, G.P.; Parwati, I.; Tjahjodjati, T.; Safriadi, F.; Situmorang, G.R.; Yohana, R.; Khairani, A.F. Molecular Dynamic Stability Study of VEGF Inhibitor in Patients with Bladder Cancer. Acta Inf. Med. 2025, 33, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bochner, B.H.; Cote, R.J.; Weidner, N.; Groshen, S.; Chen, S.-C.; Skinner, D.G.; Nichols, P.W. Angiogenesis in Bladder Cancer: Relationship Between Microvessel Density and Tumor Prognosis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995, 87, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariat, S.F.; Youssef, R.F.; Gupta, A.; Chade, D.C.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Isbarn, H.; Jeldres, C.; Sagalowsky, A.I.; Ashfaq, R.; Lotan, Y. Association of Angiogenesis Related Markers With Bladder Cancer Outcomes and Other Molecular Markers. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 1744–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaton, J.W.; Millikan, R.; Inoue, K.; Karashima, T.; Czerniak, B.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Benedict, W.F.; Dinney, C.P.N. Correlation of metastasis related gene expression and relapse-free survival in patients with locally advanced bladder cancer treated with cystectomy and chemotherapy. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarvas, T.; Becker, M.; Vom Dorp, F.; Gethmann, C.; Tötsch, M.; Bánkfalvi, Á.; Schmid, K.W.; Romics, I.; Rübben, H.; Ergün, S. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 as a marker of metastasis and predictor of poor survival in bladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, K.-P.; Ye, H.-Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hou, S.-K. Serum levels of endostatin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 associated with high stage and grade primary transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urology 2003, 61, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazargani, S.T.; Clifford, T.G.; Djaladat, H.; Schuckman, A.K.; Wayne, K.; Miranda, G.; Cai, J.; Sadeghi, S.; Dorff, T.; Quinn, D.I.; et al. Association between precystectomy epithelial tumor marker response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and oncological outcomes in urothelial bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2019, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chlewicki, L.K.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Liang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.-X. Facilitating T Cell Infiltration in Tumor Microenvironment Overcomes Resistance to PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balar, A.V.; Castellano, D.E.; Grivas, P.; Vaughn, D.J.; Powles, T.; Vuky, J.; Fradet, Y.; Lee, J.-L.; Fong, L.; Vogelzang, N.J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Results from KEYNOTE-045 and KEYNOTE-052 after up to 5 years of follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Vogelzang, N.J.; De Giorgi, U.; Oudard, S.; Retz, M.M.; Castellano, D.; Bamias, A.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Ullén, A.; Loriot, Y.; Sridhar, S.S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Bellmunt, J.; et al. Avelumab First-Line Maintenance for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma: Results From the JAVELIN Bladder 100 Trial After ≥2 Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3486–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Witjes, J.A.; Gschwend, J.E.; Milowsky, M.I.; Schenker, M.; Valderrama, B.P.; Tomita, Y.; Bamias, A.; Lebret, T.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in High-Risk Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma: Expanded Efficacy From CheckMate 274. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Park, S.H.; Garcia-Donas, J.; Huddart, R.; Burgess, E.; Fleming, M.; Rezazadeh, A.; Mellado, B.; Varlamov, S.; et al. Erdafitinib in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.B.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Bedke, J.; Valderrama, B.P.; Iyer, G.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Vulsteke, C.; Drakaki, A.; et al. Enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab in untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: 2.5-year median follow-up of the phase III EV-302/KEYNOTE-A39 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Tagawa, S.; Vulsteke, C.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Park, S.H.; Necchi, A.; De Santis, M.; Duran, I.; Morales-Barrera, R.; Guo, J.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in advanced urothelial carcinoma: TROPiCS-04, a phase III randomized trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Makker, V.; Oaknin, A.; Oh, D.-Y.; Banerjee, S.; González-Martín, A.; Jung, K.H.; Ługowska, I.; Manso, L.; Manzano, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors: Primary Results From the DESTINY-PanTumor02 Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, X.; Wang, L.; He, Z.; Shi, Y.; Luo, H.; Han, W.; Yao, X.; Shi, B.; Liu, J.; Hu, C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Disitamab Vedotin in Patients With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Positive Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Combined Analysis of Two Phase II Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, S.N.; Nisar, S.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, M.; Rizwan, A.; Hashem, S.; El-Rifai, W.; Bedognetti, D.; Batra, S.K.; Haris, M.; et al. Liquid biopsy: A step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.K.; Liao, J.; Li, M.S.; Khoo, B.L. Urine biopsy technologies: Cancer and beyond. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7872–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Lin, J.; Jin, X. Biological functions and clinical significance of long noncoding RNAs in bladder cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiadis, M.; Lee, M.; Jeffrey, S.S. Circulating Tumor Cells and Circulating Tumor DNA: Challenges and Opportunities on the Path to Clinical Utility. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4786–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simna, S.P.; Han, Z. Prospects of Non-Coding Elements in Genomic DNA Based Gene Therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2022, 22, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberca-del Arco, F.; Prieto-Cuadra, D.; De La Blanca, R.S.-P.; Sáez-Barranquero, F.; Matas-Rico, E.; Herrera-Imbroda, B. New Perspectives on the Role of Liquid Biopsy in Bladder Cancer: Applicability to Precision Medicine. Cancers 2024, 16, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, V.; Espino-Grosso, P.; Henriksen, C.H.; Canales, B.K. Office Cystoscopy Urinary Tract Infection Rate and Cost before and after Implementing New Handling and Storage Practices. Urol. Pract. 2021, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.; Stenzl, A.; Sharma, A.; Vasdev, N. Urinary biomarkers in bladder cancer: A review of the current landscape and future directions. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Huang, Y.; Qin, W.; Chen, S. Unleashing the power of urine-based biomarkers in diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring of bladder cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2025, 66, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiruba, B.; Narayan, P.S.A.; Raj, B.; Raj, S.R.; Mathew, S.G.; Lulu, S.S.; Sundararajan, V. Intervention of machine learning in bladder cancer research using multi-omics datasets: Systematic review on biomarker identification. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membribes, S.C.; Nally, E.; Jackson-Spence, F.; Graham, C.; Lalwani, S.; Szabados, B.; Powles, T. Established and emerging biomarkers approaches in urothelial carcinoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2025, 125, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, E.; Birkenkamp-Demtröder, K.; Nordentoft, I.; Høyer, S.; Van Der Keur, K.; Van Kessel, K.; Zwarthoff, E.; Agerbæk, M.; Ørntoft, T.F.; Jensen, J.B.; et al. Liquid Biopsy Analysis of FGFR3 and PIK3CA Hotspot Mutations for Disease Surveillance in Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukers, W.; Van Der Keur, K.A.; Kandimalla, R.; Vergouwe, Y.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Boormans, J.L.; Jensen, J.B.; Lorente, J.A.; Real, F.X.; Segersten, U.; et al. FGFR3, TERT and OTX1 as a Urinary Biomarker Combination for Surveillance of Patients with Bladder Cancer in a Large Prospective Multicenter Study. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-W.; Wang, Y.-R.; Fan, G.-R.; Niu, Q.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Wang, H.; Svatek, R.; Rodriguez, R.; Wang, Z.-P. Diagnostic and prognostic role of BTA, NMP22, survivin and cytology in urothelial carcinoma. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3192–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeyen, E.; Hoekx, L.; De Wachter, S.; Baldewijns, M.; Ameye, F.; Mertens, I. Bladder Cancer Diagnosis and Follow-Up: The Current Status and Possible Role of Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: Cancer screening and early detection. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.; La Civita, E.; Liotti, A.; Cennamo, M.; Tortora, F.; Buonerba, C.; Crocetto, F.; Lucarelli, G.; Busetto, G.M.; Del Giudice, F.; et al. Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers in Urine: A Route towards Molecular Diagnosis and Personalized Medicine of Bladder Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, R.; Buckley, D.; Fu, R.; Gore, J.L.; Gustafson, K.; Griffin, J.; Grusing, S.; Selph, S. Emerging Approaches to Diagnosis and Treatment of Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer; AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2015. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK330472/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Sassa, N.; Iwata, H.; Kato, M.; Murase, Y.; Seko, S.; Nishikimi, T.; Hattori, R.; Gotoh, M.; Tsuzuki, T. Diagnostic Utility of UroVysion Combined With Conventional Urinary Cytology for Urothelial Carcinoma of the Upper Urinary Tract. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 151, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Han, C.; Hao, L.; Zang, G. ImmunoCyt test compared to cytology in the diagnosis of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Fan, C.; Su, M.; Wang, Q.; Bao, H. Use of the Nuclear Matrix Protein 22 BladderChek Test for the Detection of Primary and Recurrent Urothelial Carcinoma. Dis. Mark. 2020, 2020, 3424039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feber, A.; Dhami, P.; Dong, L.; De Winter, P.; Tan, W.S.; Martínez-Fernández, M.; Paul, D.S.; Hynes-Allen, A.; Rezaee, S.; Gurung, P.; et al. UroMark—A urinary biomarker assay for the detection of bladder cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Loloi, J.; Martina, L.P.; Sankin, A. The Development of Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tools in Bladder Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2022, 15, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverink, C.A.; Batista, R.P.M.; Prazeres, H.J.M.; Vinagre, J.; Sampaio, C.; Leão, R.R.; Máximo, V.; Witjes, J.A.; Soares, P. Clinical Validation of a Urine Test (Uromonitor-V2®) for the Surveillance of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer Patients. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avogbe, P.H.; Manel, A.; Vian, E.; Durand, G.; Forey, N.; Voegele, C.; Zvereva, M.; Hosen, M.I.; Meziani, S.; De Tilly, B.; et al. Urinary TERT promoter mutations as non-invasive biomarkers for the comprehensive detection of urothelial cancer. eBioMedicine 2019, 44, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Righetto, M.; Zumerle, S.; Montopoli, M.; Zattoni, F. The Bladder EpiCheck Test as a Non-Invasive Tool Based on the Identification of DNA Methylation in Bladder Cancer Cells in the Urine: A Review of Published Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roperch, J.-P.; Hennion, C. A novel ultra-sensitive method for the detection of FGFR3 mutations in urine of bladder cancer patients—Design of the Urodiag® PCR kit for surveillance of patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). BMC Med. Genet. 2020, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chauhan, P.S.; Babbra, R.K.; Feng, W.; Pejovic, N.; Nallicheri, A.; Harris, P.K.; Dienstbach, K.; Atkocius, A.; Maguire, L.; et al. Tracking minimal residual disease with urine tumor DNA in muscle-invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, e16514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierconti, F.; Martini, M.; Fiorentino, V.; Cenci, T.; Capodimonti, S.; Straccia, P.; Sacco, E.; Pugliese, D.; Cindolo, L.; Larocca, L.M.; et al. The combination cytology/epichek test in non muscle invasive bladder carcinoma follow-up: Effective tool or useless expence? Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, e17–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, X.-H.; Wu, X.-H.; He, G.-X.; Xie, L.-M.; Cao, X.-J.; Guo, X.-G. Pooled analysis of Xpert Bladder Cancer based on the 5 mRNAs for rapid diagnosis of bladder carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-L.; Chen, J.; Yan, W.; Zang, D.; Qin, Q.; Deng, A.-M. Diagnostic accuracy of cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21–1) for bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 3137–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.; Sharples, K.; Dalphin, M.; Davidson, P.; Gilling, P.; Cambridge, L.; Harvey, J.; Toro, T.; Giles, N.; Luxmanan, C.; et al. A Multigene Urine Test for the Detection and Stratification of Bladder Cancer in Patients Presenting with Hematuria. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirasawa, Y.; Pagano, I.; Chen, R.; Sun, Y.; Dai, Y.; Gupta, A.; Tikhonenkov, S.; Goodison, S.; Rosser, C.J.; Furuya, H. Diagnostic performance of OncuriaTM, a urinalysis test for bladder cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Cui, J.; Chen, K.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tao, J.; Han, Z.; Zhang, W.; Song, R.; Gu, M. Diagnostic accuracy of the UBC® Rapid Test for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 3770–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Mungadi, I.; Darlington, N.; Kalayi, G. Effectiveness of bladder tumor antigen quantitative test in the diagnosis of bladder carcinoma in a schistosoma endemic area. Urol. Ann. 2019, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, A.; Manousakas, T.; Mitropoulos, D.; Botsoli-Stergiou, E.; Constantinides, C.; Giannopoulou, M.; Choremi-Papadopoulou, H. Comparative evaluation of the BTAstat test, NMP22, and voided urine cytology in the detection of primary and recurrent bladder tumors. Urology 2000, 55, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Brás, J.P.; Dias, C.; Bessa-Gonçalves, M.; Botelho, F.; Silva, J.; Silva, C.; Pacheco-Figueiredo, L. Uromonitor: Clinical Validation and Performance Assessment of a Urinary Biomarker Within the Surveillance of Patients With Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. J. Urol. 2025, 213, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.; Mantica, G.; Ambrosini, F.; Calarco, A.; Tufano, A.; Borges De Souza, P.; Mazza, M.; Bravaccini, S. The current status of biomarkers for bladder cancer: Progress and challenges. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 77, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Y. Development and validation of interpretable machine learning models to predict distant metastasis and prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, Y.; Roehrborn, C.G. Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: Results of a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses. Urology 2003, 61, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dorp, J.; Pipinikas, C.; Suelmann, B.B.M.; Mehra, N.; Van Dijk, N.; Marsico, G.; Van Montfoort, M.L.; Hackinger, S.; Braaf, L.M.; Amarante, T.; et al. Author Correction: High- or low-dose preoperative ipilimumab plus nivolumab in stage III urothelial cancer: The phase 1B NABUCCO trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Kockx, M.; Rodriguez-Vida, A.; Duran, I.; Crabb, S.J.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Szabados, B.; Pous, A.F.; Gravis, G.; Herranz, U.A.; et al. Clinical efficacy and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in operable urothelial carcinoma in the ABACUS trial. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.B.; Birkenkamp-Demtröder, K.; Nordentoft, I.; Milling, R.V.; Körner, S.K.; Brandt, S.B.; Knudsen, M.; Lam, G.W.; Dohn, L.H.; Fabrin, K.; et al. 1960O Identification of bladder cancer patients that could benefit from early post-cystectomy immunotherapy based on serial circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) testing: Preliminary results from the TOMBOLA trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolitsis, I.; Kapriniotis, K.; Katsimperis, S.; Angelopoulos, P.; Triantafyllou, P.; Karagiotis, T.; Juliebo-Jones, P.; Mitsogiannis, I.; Somani, B.; Skolarikos, A.; et al. The use of ctDNA for muscle-invasive bladder cancer before and after radical cystectomy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2025, 25, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Chang, Y.-H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Munoz, J.; Reyes-Cosmelli, F.; Peer, A.; Cohen, G.; Yu, E.Y.; Lorch, A.; Bavle, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Exploratory ctDNA biomarker analyses of the KEYNOTE-361 phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2508–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, D.; Zang, J.; Qian, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Xie, F.; Tang, H.; Xia, J.; et al. Disitamab vedotin combined with toripalimab and radiotherapy for multimodal organ-sparing treatment of muscle invasive bladder cancer: A proof-of-concept study. Neoplasia 2025, 68, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, P.H.; Milowsky, M.I.; Petrylak, D.P.; Hoimes, C.J.; Flaig, T.W.; Mar, N.; Moon, H.H.; Friedlander, T.W.; McKay, R.R.; Bilen, M.A.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin With or Without Pembrolizumab in Cisplatin-Ineligible Patients With Previously Untreated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4107–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, K.R.; Jindal, T.; Mitchell, B.; Zhu, X.; Ding, C.-K.C.; Desai, A.; Wong, A.C.; Younger, N.S.; Kwon, D.H.; De Kouchkovsky, I.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) monitoring in patients (pts) with advanced urothelial carcinoma (aUC) treated with enfortumab vedotin +/- pembrolizumab (EVP). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.S.; Shiang, A.; Alahi, I.; Sundby, R.T.; Feng, W.; Gungoren, B.; Nawaf, C.; Chen, K.; Babbra, R.K.; Harris, P.K.; et al. Urine cell-free DNA multi-omics to detect MRD and predict survival in bladder cancer patients. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfakianos, J.P.; Basu, A.; Laliotis, G.; Cumarasamy, S.; Rich, J.M.; Kommalapati, A.; Glover, M.; Mahmood, T.; Tillu, N.; Hoimes, C.J.; et al. Association of Tumor-informed Circulating Tumor DNA Detectability Before and After Radical Cystectomy with Disease-free Survival in Patients with Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariathasan, S.; Turley, S.J.; Nickles, D.; Castiglioni, A.; Yuen, K.; Wang, Y.; Kadel, E.E., III; Koeppen, H.; Astarita, J.L.; Cubas, R.; et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 2018, 554, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Shen, Y.; Wen, S.; Yamada, S.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Gnjatic, S.; Bajorin, D.F.; Reuter, V.E.; Herr, H.; Old, L.J.; et al. CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are predictive of survival in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3967–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; John, J.; Wang, J.H. Why responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors are heterogeneous in head and neck cancers: Contributions from tumor-intrinsic and host-intrinsic factors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 995434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.P.; Marciscano, A.E.; Drake, C.G.; Vignali, D.A.A. LAG 3 (CD 223) as a cancer immunotherapy target. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 276, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougall, W.C.; Kurtulus, S.; Smyth, M.J.; Anderson, A.C. TIGIT and CD 96: New checkpoint receptor targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 276, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Gao, F.; Liu, Y.; Shao, J. Survival and clinicopathological significance of B7-H3 in bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Hamad, M.; Elkord, E. TIGIT in cancer: From mechanism of action to promising immunotherapeutic strategies. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascierto, P.A.; Lipson, E.J.; Dummer, R.; Larkin, J.; Long, G.V.; Sanborn, R.E.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Dréno, B.; Dalle, S.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Nivolumab and Relatlimab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma That Had Progressed on Anti–Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy: Results From the Phase I/IIa RELATIVITY-020 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2724–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Mishra, S.; Jain, D.; Ludhiani, S.; Rajput, A. Artificial Intelligence. In Bioinformatics Tools and Big Data Analytics for Patient Care; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 71–90. ISBN 978-1-003-22694-9. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003226949/chapters/10.1201/9781003226949-5 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Crocetto, F.; Amicuzi, U.; Musone, M.; Magliocchetti, M.; Di Lieto, D.; Tammaro, S.; Pastore, A.L.; Fuschi, A.; Falabella, R.; Ferro, M.; et al. Liquid Biopsy: Current advancements in clinical practice for bladder cancer. J. Liq. Biopsy 2025, 9, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashkami, A.; Nasayreh, A.; Makhadmeh, S.N.; Gharaibeh, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alwadain, A.; Heming, J.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L. A review of Artificial Intelligence methods in bladder cancer: Segmentation, classification, and detection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; He, L.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, J.; Cai, S.; Cai, H.; Yu, B. Artificial intelligence application in the diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer: Advance, challenges, and opportunities. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1487676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolyar, E.; Jia, X.; Chang, T.C.; Trivedi, D.; Mach, K.E.; Meng, M.Q.-H.; Xing, L.; Liao, J.C. Augmented Bladder Tumor Detection Using Deep Learning. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, T.A.; Chen, X.; Xie, Y.; Murakami, K.; Sakatani, T.; Kita, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyake, M.; Knott, S.R.V.; Li, D.; et al. MRI/RNA-Seq-Based Radiogenomics and Artificial Intelligence for More Accurate Staging of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gomez, J.; Madero, R.; Solsona, E.; Unda, M.; Martinez-Piñeiro, L.; Gonzalez, M.; Portillo, J.; Ojea, A.; Pertusa, C.; Rodriguez-Molina, J.; et al. Predicting Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Recurrence and Progression in Patients Treated With Bacillus Calmette-Guerin: The CUETO Scoring Model. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shen, R.; Hong, G.; Luo, Y.; Wan, H.; Feng, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liao, C.; et al. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence-based model for detecting urothelial carcinoma using urine cytology images: A multicentre, diagnostic study with prospective validation. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, C. Artificial intelligence for diagnosing bladder pathophysiology: An updated review and future prospects. Bladder 2025, 12, e21200042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecular Subtype | Key Biomarkers | Clinical Implications | Therapeutic/Response Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LumP | FGFR3 mutations/fusions/amplifications (~55%), KDM6A mutations (~38%), CDKN2A deep deletions (~33%) | 24–35% of MIBC. Most favorable prognosis (5-year OS ≈ 65–70%); enriched in younger patients and T2 tumors. | Likely sensitive to FGFR3 inhibitors (erdafitinib, BGJ398); potential biomarker for targeted therapy |

| LumNS | ELF3 mutations (~35%), PPARG alterations (amplifications/fusions ~76%) | 8–12% of MIBC. Older patients (>80 yr), micropapillary histology, carcinoma in situ association. Intermmediate outcomes(5-year OS ≈ 50–55%) | Potential benefit from NAC; some enrichment in atezolizumab responders |

| LumU | PPARG alterations (~89%), ERBB2 amplification (~39%), TP53 mutations (~76%), ERCC2 mutations (~22%), high CNA and mutation load | 15–20% of MIBC. Most genomically altered class; poor prognosis trend; high cell cycle activity. Inferior survival (5-year OS ≈ 40–45%) | Potential sensitivity to ERBB2-targeted therapy; association with radiotherapy response; enrichment for atezolizumab response |

| Ba/Sq | TP53 mutations (~61%), RB1 mutations (~25%), concurrent TP53+RB1 in ~14%, EGFR pathway activation, STAT3/HIF1A regulon activity | 20–35% of MIBC. Enriched in females, advanced stage, squamous differentiation; poor prognosis (5-year OS ≈ 35–45%). | Potential sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors; high immune infiltration and immune checkpoint expression → candidates for immunotherapy; possible benefit from NAC |

| NE-like | Ubiquitous TP53 (94%) + RB1 (94%) alterations, high cell cycle activity, neuroendocrine histology (~72%) | Worst prognosis (median OS < 24 months even with multimodal therapy), highly aggressive, rare (~3%) | Potential sensitivity to ICIs; potential radiotherapy responders; parallels with small cell carcinoma treatment |

| SR | High stromal gene expression, no specific driver mutation | ~15% of MIBC. Intermediate survival (5-year OS ≈ 50%). Histology is dominated by stroma | Immune infiltration (T/B cell) but lower ICI response; limited sensitivity to NAC |

| Test | Variable | Biomarker | Assay | Clinical Application | Sensibility/Specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urovysion | Chromosome 3-7-9-17 | DNA/Sediment cells | FISH | Post BCG/early recurrence | 69%/76% | [73] |

| Immunocyt | CEA, MAUB | Antigens and sulfated mucin glycoproteins (sediment cells) | Immunofluorescence cytology | LG-NMIBC diagnosis | 77.5%/62.5% | [74] |

| Uromark | Epigenetic alterations | Sediment cells/DNA | NGS + BS-Seq PCR | Predictive and monitoring treatment | 95%/96% | [76] |

| NMP22 (Bladder Chek) | NMP22 | Protein | ELISA + POC immunoassay | Early diagnosis and monitoring HG recurrence | 59%/93% | [68,75] |

| Uromonitor | FGFR3, TERT, KRAS | DNA | PCR | Predictive (recurrence) | 73.5%/93.2% | [78,91] |

| Uromutert | TERT | DNA | NGS PCR | Early diagnosis | 87.1%/94.7% | [79] |

| Bladder Epicheck | DNA methylation | DNA | RT-PCR | Early diagnosis of HG-NMIBC | 81%/83% | [80] |

| Uroseek | TERT, FGRF3, TP53, CDKN2A, ERB2, HRAS, PIK3CA, METH, BHL, MLL | DNA | SafeSeqS | Early diagnosis and monitoring response | 95%/93% | [66] |

| Urodiag | FGFR3, HS3ST2, SEPT9, SLIT2 | DNA | DNA methylation + MASO-PCR | Monitoring HG recurrence | 95.5%/75.9% | [81] |

| CxBladder | CDK1, MDK, HOXA13, IGFBP5, CXCR2 | mRNA | qPCR | Early diagnosis | 82%/85% | [82,83] |

| ADXBLADDER | MCM | Protein | ELISA | Predictive (≳T1 disease) | 73%/68.4% | [83] |

| Xpert BC | ABL1, UPK1B, CRH, ANXA10, IGF2 | mRNA | RT-PCR | Exclude recurrence | 76%/85% | [84] |

| CYFRA 21.1 | Cytokeratin19 | Protein | ELISA | Diagnosis | 82%/80% | [85] |

| AssureMDx | FGFR3, TERT, HRAS, OTX1, ONECUT2, TWIST1 | DNA | DNA methylation + PCR | Predictive (HG-NMIBC) | 93%/86% | [86] |

| Oncuria | ANG, APOE, A1AT, CA9, IL8, MMP9, PAI1, SDC1, VEGF | Protein | Immunoassay | Diagnosis and follow-up | 85%/81% | [87] |

| UBC Rapid | Cytokeratin 8 and 18 | Protein | POC immunoassay | Predictive (Cis) | 70.8%/61.4% | [88] |

| BTA test | BTA | Protein | Immunochromatography + ELISA | Diagnosis and monitoring response | 56%/85.7% | [68,89,90] |

| Trial | Setting | Drug | Primary Objective | Secondary Objectives | Design | ctDNA Measurement | Preliminary Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NABUCCO | Neoadjuvant | Ipilimumab + nivolumab | Safety and feasibility | pCR rate and exploratory studies PD-L1 status, TMB, and immune cell infiltration) | Prospective, phase Ib | Before and after neoadjuvant immunotherapy | pCR ~46%; ctDNA clearance correlated with response; ctDNA persistence predicted relapse [95] |

| ABACUS | Neoadjuvant | Atezolizumab | pCR rate | Disease-free survival (DFS), OS, radiological response (RR) | Prospective, phase II | Baseline and post-neoadjuvant immunotherapy | pCR 31%; ctDNA negativity associated with pCR and better RFS; persistent ctDNA predicted relapse [96] |

| IMvigor010 | Adjuvant | atezolizumab vs. observation | DFS | OS, safety, exploratory biomarker analyses (including ctDNA) | Prospective, phase III, post hoc ctDNA analysis | Post-cystectomy (MRD detection) | No DFS benefit overall; ctDNA+ patients derived benefit from atezolizumab; ctDNA– did not [47] |

| TOMBOLA | Adjuvant | Atezolizumab | Validation of ctDNA as a biomarker of MRD and predictor of recurrence | Time to recurrence, OS, ctDNA detection vs. radiological imaging | Prospective, observational, multicenter | Baseline, post-surgery, follow-up | ctDNA positivity post-cystectomy predicted early relapse and preceded radiologic recurrence [97] |

| MODERN | Adjuvant | Nivolumab | DFS in ctDNA-guided adjuvant therapy vs. standard-of-care | OS, cost-effectiveness, safety, quality of life, ctDNA assay validation | Prospective, phase III, randomized | Post-cystectomy | Ongoing [98] |

| KEYNOTE-361 | Advanced/metastatic | Pembrolizumab ± chemotherapy | OS, PFS | Objective response rate (ORR), duration of response (DoR), safety, exploratory biomarkers (including ctDNA) | Prospective, phase III, exploratory biomarker analysis | Baseline and on-treatment | Not meet OS/PFS; ctDNA dynamics associated with survival and treatment response [99] |

| NCT05979740 | Organ-preserving multimodal therapy | Disitamab vedotin + toripalimab + RT | Safety and feasibility | ORR, ctDNA dynamics for recurrence monitoring, recurrence-free survival (RFS) | Prospective, early phase | During treatment and follow-up | Feasible and safe; ctDNA dynamics used to monitor recurrence and treatment response [100] |

| EV-103 | Advanced/metastatic | EV ± pembrolizumab | Safety and efficacy, ORR | Duration of response (DoR), PFS, OS, exploratory biomarkers (ctDNA, PD-L1 | Prospective, phase Ib/II | Baseline and during treatment | EV ± pembro: ORR 64.5%, median DoR 13.2 months; exploratory ctDNA analyses ongoing [101] |

| EV-302/KEYNOTE-A39 | Advanced/metastatic | EV + pembrolizumab vs. chemotherapy | OS, PFS | ORR, DoR, safety, quality of life, exploratory biomarkers (including ctDNA) | Prospective, phase III, randomized | Baseline and on-treatment | EV+pembro vs. chemo: OS 31.5 vs. 16.1 months; HR death 0.47; PFS 12.5 vs. 6.3 months; ORR 67.7% vs. 44.4%; ctDNA analysis ongoing [102] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alberca-del Arco, F.; Santos-Perez de la Blanca, R.; Matas-Rico, E.M.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Guerrero-Ramos, F. Emerging Molecular and Computational Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma: Innovations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Prediction. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010025

Alberca-del Arco F, Santos-Perez de la Blanca R, Matas-Rico EM, Herrera-Imbroda B, Guerrero-Ramos F. Emerging Molecular and Computational Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma: Innovations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Prediction. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlberca-del Arco, Fernando, Rocío Santos-Perez de la Blanca, Elisa Maria Matas-Rico, Bernardo Herrera-Imbroda, and Félix Guerrero-Ramos. 2026. "Emerging Molecular and Computational Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma: Innovations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Prediction" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010025

APA StyleAlberca-del Arco, F., Santos-Perez de la Blanca, R., Matas-Rico, E. M., Herrera-Imbroda, B., & Guerrero-Ramos, F. (2026). Emerging Molecular and Computational Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma: Innovations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Prediction. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010025