Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in Critically Ill Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methods, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

2.2. Outcome

2.3. Risk of Bias

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Studies’ Selection and Characteristics

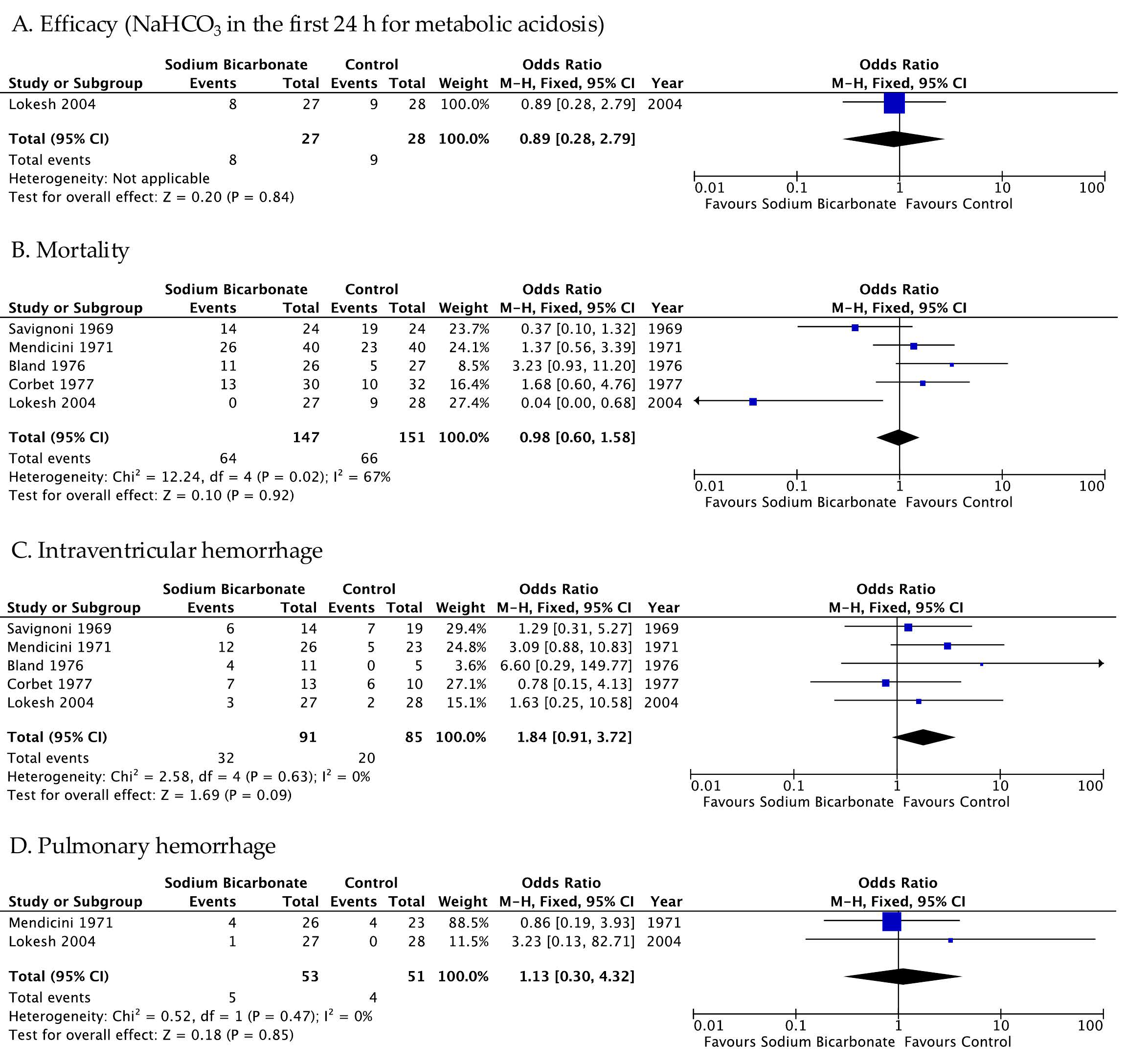

3.2. Primary Outcome

3.2.1. Evidence from Randomized Controlled Trials

3.2.2. Evidence from Unrandomized Controlled Trials

3.3. Secondary Outcome

3.3.1. Evidence from Randomized Controlled Trials

3.3.2. Evidence from Unrandomized Controlled Trials

3.4. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BE | Base excess |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| BW | Birth weight |

| CBV | Cerebral blood volume |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| GA | Gestational age |

| HIE | Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy |

| HMD | Hyaline membrane disease |

| IVH | Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| MA | Metabolic acidosis |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NDV | Neurodevelopmental |

| ND | Not declared |

| NEC | Necrotizing enterocolitis |

| NICUs | Neonatal intensive care units |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SB | Sodium bicarbonate |

| SGA | Small for gestational age |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

References

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Villanueva-García, D.; Solimano, A.; Muns, R.; Ibarra-Ríos, D.; Mota-Reyes, A. Pathophysiology of Perinatal Asphyxia in Humans and Animal Models. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobelli, S.; Guignard, J.-P. Renal Aspects of Metabolic Acid–Base Disorders in Neonates. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2020, 35, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nada, A.; Bonachea, E.M.; Askenazi, D.J. Acute Kidney Injury in the Fetus and Neonate. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitar, L.; Kota, S.; Machie, M.; Mashat, S.; Liu, Y.-L.; Chalak, L.F. Multi-Organ Involvement in Preterm Neonatal Encephalopathy. Early Hum. Dev. 2025, 208, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A.; Riskin, A.; Sharkansky, L.; Hijazi, R.; Ghannam, R.; Zaitoon, H. Short-Term Clinical and Biochemical Outcomes of Infants Born After 34 Weeks of Gestation with Mild-to-Moderate Cord Blood Acidosis—A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notz, L.; Adams, M.; Bassler, D.; Boos, V. Association between Early Metabolic Acidosis and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia/Death in Preterm Infants Born at Less than 28 Weeks’ Gestation: An Observational Cohort Study. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Sahni, R. Uses and Misuses of Sodium Bicarbonate in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 22, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, C.J.; Weir, F.J.; McGuire, W. Base Administration or Fluid Bolus for Preventing Morbidity and Mortality in Preterm Infants with Metabolic Acidosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2010, CD003215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Strand, M.L.; Finan, E.; Illuzzi, J.; Kamath-Rayne, B.D.; Kapadia, V.; Mahgoub, M.; Niermeyer, S.; Schexnayder, S.M.; Schmölzer, G.M.; et al. Part 5: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2025 American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics 2025, 157, e2025074352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogeveen, M.; Monnelly, V.; Binkhorst, M.; Cusack, J.; Fawke, J.; Kardum, D.; Roehr, C.C.; Rüdiger, M.; Schwindt, E.; Solevåg, A.L.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2025 Newborn Resuscitation and Support of Transition of Infants at Birth. Resuscitation 2025, 215, 110766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhugga, G.; Sankaran, D.; Lakshminrusimha, S. ABCs of Base Therapy in Neonatology: Role of Acetate, Bicarbonate, Citrate and Lactate. J. Perinatol. 2025, 45, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canani, R.; Terrin, G.; Elce, A.; Pezzella, V.; Heinz-Erian, P.; Pedrolli, A.; Centenari, C.; Amato, F.; Tomaiuolo, R.; Calignano, A.; et al. Genotype-Dependency of Butyrate Efficacy in Children with Congenital Chloride Diarrhea. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvia, G.; Cascioli, C.F.; Ciccimarra, F.; Terrin, G.; Cucchiara, S. A Case of Protein-Losing Enteropathy Caused by Intestinal Lymphangiectasia in a Preterm Infant. Pediatrics 2001, 107, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massenzi, L.; Aufieri, R.; Donno, S.; Agostino, R.; Dotta, A. Use of Intravenous Sodium Bicarbonate in Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Italy: A Nationwide Survey. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehri, H.; Alqahtani, R.; Alromih, A.M.; Altamimi, A.; Alshehri, K.; Almehaideb, L.; Jabari, M.; Alzayed, A. The Practices of Intravenous Sodium Bicarbonate Therapy in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Multi-Country Survey. Medicine 2023, 102, e34337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraky, A.M.; Yerramalla, Y.; Khan, A.; Mokhtar, Y.; Wright, A.; Alsabbagh, W.; Franco Valle, K.; Haleem, M.; Kennedy, K.; Boulware, C. Complexities, Benefits, Risks, and Clinical Implications of Sodium Bicarbonate Administration in Critically Ill Patients: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.S.; Graver, M.L.; Urivetsky, M.; Scharf, S.M. Mechanisms of Myocardial Depression after Bolus Injection of Sodium Bicarbonate. J. Crit. Care 1994, 9, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.C.; Lassen, N.A.; Friis-Hansen, B. Impaired Autoregulation of Cerebral Blood Flow in the Distressed Newborn Infant. J. Pediatr. 1979, 94, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.C.; Lassen, N.A.; Friis-Hansen, B. Decreased Cerebral Blood Flow after Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in the Distressed Newborn Infant. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1978, 57, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synnes, A.R.; Chien, L.-Y.; Peliowski, A.; Baboolal, R.; Lee, S.K. Variations in Intraventricular Hemorrhage Incidence Rates among Canadian Neonatal Intensive Care Units. J. Pediatr. 2001, 138, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024); Welch, V.A., Ed.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Savignoni, P.G.; Bucci, G.; Ceccamea, A.; Mendicini, M.; Scalamandre, A.; Orzalesi, M.M. Intravenous Infusion of Glucose and Sodium Bicarbonate in Hyaline Membrane Disease a Controlled Trial. Acta Paediatr. 1969, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendicini, M.; Scalamandrb, A.; Savignoni, P.G.; Picece-Bucci, S.; Esuperanzi, R.; Bucci, G. A Controlled Trial on Therapy for Newborns Weighing 750-1 250 g I. Clinical Findings and Mortality in the Newborn Period. Acta Paediatr. 1971, 60, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, R.D.; Clarke, T.L.; Harden, L.B. Rapid Infusion of Sodium Bicarbonate and Albumin into High-Risk Premature Infants Soon after Birth: A Controlled, Prospective Trial. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 1976, 124, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, A.J.; Adams, J.M.; Kenny, J.D.; Kennedy, J.; Rudolph, A.J. Controlled Trial of Bicarbonate Therapy in High-Risk Premature Newborn Infants. J. Pediatr. 1977, 91, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoff, H.; Manzl, F.; Diekmann, L.; Kunzl, C.; Stock, G.J.; Weisser, F. Decreased Growth Rate of Low-Birth-Weight Infants with Prolonged Maximum Renal Acid Stimulation. Acta Paediatr. 1993, 82, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoff, H.; Diekmann, L.; Kunz, C.; Stock, G.J.; Manz, F. Alkali Therapy versus Sodium Chloride Supplement in Low Birthweight Infants with Incipient Late Metabolic Acidosis. Acta Paediatr. 1997, 86, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, H.; Hawkins, K.; Stephenson, T. Comparison of Albumin versus Bicarbonate Treatment for Neonatal Metabolic Acidosis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1999, 158, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, L.; Kumar, P.; Murki, S.; Narang, A. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Sodium Bicarbonate in Neonatal Resuscitation—Effect on Immediate Outcome. Resuscitation 2004, 60, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alfen-van Der Velden, A.A.E.M.; Hopman, J.C.W.; Klaessens, J.H.G.M.; Feuth, T.; Sengers, R.C.A.; Liem, K.D. Effects of Rapid versus Slow Infusion of Sodium Bicarbonate on Cerebral Hemodynamics and Oxygenation in Preterm Infants. Biol. Neonate 2006, 90, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuo, E.; Lyden, E.R.; Peeples, E.S. Effect of Early Clinical Management on Metabolic Acidemia in Neonates with Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. J. Perinatol. 2024, 44, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritzke, A.; Thomas, S.; Amin, H.; Fusch, C.; Lodha, A. Renal Consequences of Preterm Birth. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, H.; Simeoni, U.; Guignard, J.-P.; Boubred, F. Preterm Birth: Long Term Cardiovascular and Renal Consequences. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2018, 14, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, T.W.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, H.W.; Yoo, Y.M. Metabolic Acidosis as a Risk Factor for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants Born between 23 + 0 and 31 + 6 Weeks of Gestation: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1595348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fee, S.C.; Malee, K.; Deddish, R.; Minogue, J.P.; Socol, M.L. Severe Acidosis and Subsequent Neurologic Status. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 1990, 162, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.J.; Walley, K.R.; Wiggs, B.R.; Russell, J.A. Bicarbonate Does Not Improve Hemodynamics in Critically III Patients Who Have Lactic Acidosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 112, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, J.A.; Madias, N.E. Metabolic Acidosis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2010, 6, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Arias, J.; Bassuk, J.; Doods, H.; Seidler, R.; Adams, J.A.; Abraham, W.M. Na+/H+ Exchange Inhibition Delays the Onset of Hypovolemic Circulatory Shock in Pigs. Shock 2008, 29, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, L.G.; Hodgson, L.E.; Selby, N.M. The Janus Faces of Bicarbonate Therapy in the ICU: Not Sure! Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlbach, B.K.; Schmidt, G.A. Bench-to-Bedside Review: Treating Acid–Base Abnormalities in the Intensive Care Unit—The Role of Buffers. Crit. Care 2004, 8, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID, Country | Inclusion Criteria | Intervention n | Control n |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | |||

| Savignoni 1969, Italy [23] |

| NaHCO3 (mEq given = BE in mEq/L × BW in Kg × 0.5 in 2–6 h) + GS 10% (70 mL/kg/d) n = 24 | GS 10% (25 mL/Kg/d) n = 24 |

| Mendicini 1971, Italy [24] |

| NaHCO3 (mEq given = BE, mEq/L × BW in kg, × 0.5, given in 2–6 h + GS 10% (70 mL/kg/d) for at least 4 days n = 40 | GS 10% (25 mL/kg/day) from 2nd to 5th day n = 40 |

| Bland 1976, USA [25] | Hypoproteinemia (cord serum total protein level of 4.6 gm/100 mL or less) and GA < 37 wks | I1: 3 mL/kg of NaHCO3 and 5 mL/kg of water n = 13 I2: 1.5 mL/kg of NaHCO3, 4 mL/kg of salt-poor albumin, and 2.5 mL/kg of water n = 13 n total 26 | C1: 8 mL/kg of glucose in water n = 13 C2: 8 mL/kg of salt-poor albumin n = 14 n total 27 |

| Corbet 1977, Texas [26] |

| NaHCO3 as following: pH 7.25–7.30, 5 mEq/dL; pH 7.15–7.25, 10 mEq/dL; pH < 7.15–15 mEq/dL + GS 10% (65 mL/kg/d) n = 30 | GS 10% (65 mL/kg/d) n = 32 § |

| Kalhoff 1993, Germany [27] | Premature babies with BW ≤ 1.5 kg or SGA with BW ≥ 1.5 kg. | Oral NaHCO3 2 mmol/kg/d for 7 days n = 77 | No NaHCO3 n = 93 |

| Kalhoff 1997, Germany [28] | Premature infants and SGA from 1.0 to 1.9 kg | Oral NaHCO3 2 mmol/kg/d for 7 days n = 27 | Oral NaCL 2 mmol/kg/d for 7 days n = 26 |

| Dixon 1999, United Kingdom [29] | pH < 7.25 and BE worse than −6. | 4.2% NaHCO3 at a dose in mmol of one-sixth × weight (kg) × BE infused over 30 min. n = 16 | 10 mL/kg 4.5% human albumin n = 20 |

| Lokesh 2004, India [30] | Asphyxiated neonates continuing to need positive pressure ventilation at 5 min of life | NaHCO3 4 mL/kg (1.8 meq/kg) over 3–5 min n = 27 | 4 mL/kg of GS 5% n = 28 |

| van Alfen-van der Velden 2006, The Netherlands [31] | GA between 26 and 34 wks with metabolic acidosis | NaHCO3 administered within approximately 15 s (Rapid group) n = 15 | NaHCO3 over a 30 min period (Slow group) n = 14 |

| Retrospective cohort study | |||

| Thuo 2024, USA [32] | ≥35 wks of GA, with moderate or severe HIE | NaHCO3 n = 39 | No NaHCO3 n = 90 |

| Study ID | Efficacy (Resolution of MA) | Mortality | IVH | PH | NDV Impairment | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savignoni 1969 [23] | Not available dichotomous data | I: 14 vs. C: 19 p value = 0.076 | I: 6 vs. C: 7 (post-mortem) p value ND | / | / | / |

| Mendicini 1971 [24] | / | I: 26 vs. C: 23 p value > 0.05 | I: 12 vs. C: 5 (post-mortem) p value = 0.07 | I: 4 vs. C: 4 (post-mortem) p value > 0.05 | Cloni I: 2 vs. C: 5 Increased tonus I: 0 vs. C: 4 Seizures I: 0 vs. C: 0 p value > 0.05 | No difference in BP between the two group, in the first 4 days of life |

| Bland 1976 [25] | Not available dichotomous data | I1: 6 I2: 5 C1: 1 C2: 4 I total: 11 C total: 5 p value ND | I1: 3 I2: 1 C1: 0 C2: 0 I total: 4 C total: 0 (post-mortem) p value ND | / | / | / |

| Corbet 1977 [26] | Not available dichotomous data | I: 13 vs. C: 10 p value > 0.05 | I: 7 vs. C: 6 (post-mortem) p value > 0.5 | / | / | NEC I: 1 vs. C: 0 (post-mortem) p value ND Sepsis I: 3 vs. C: 1 (post-mortem) p value ND |

| Kalhoff 1993 [27] | Not available dichotomous data | ND | ND | / | / | / |

| Kalhoff 1997 [28] | Not available dichotomous data | ND | ND | / | / | / |

| Dixon 1999 [29] | Not available dichotomous data | ND | ND | / | / | / |

| Lokesh 2004 [30] | Need of NaHCO3 in the first 24 h I: 8 vs. C: 9 p value > 0.05 | I: 0 vs. C: 9 p value 0.84 | I: 3 vs. C: 2 p value > 0.05 | I: 1 vs. C: 0 p value > 0.05 | Neurological abnormality at discharge I: 5 vs. C: 6 (Percentage out of survivors) p value 0.10 Encephalopathy I: 20 vs. C: 18 p value > 0.05 Cerebral edema on ultrasonography I: 14 vs. C: 9 p value > 0.05 | Need for volume expansion I: 10 vs. C: 8 p value > 0.05 Inotropic support I: 12 vs. C: 8 p value > 0.05 PPHN I: 1 vs. C: 0 p value > 0.05 |

| Study ID | Efficacy (Resolution of MA) | Mortality | IVH | PH | NDV Impairment | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Alfen-van der Velden 2006 [31] | Not available dichotomous data | / | / | / | / | Infusion of NaHCO3 resulted in a statistically significant increase in CBV over time in both groups (p < 0.001 rapid group; p < 0.01 slow group). |

| Study ID | Efficacy (Resolution of MA) | Mortality | IVH | PH | NDV Impairment | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thuo 2024 [32] | Not available dichotomous data | I: 5 vs. C: 1 p value 0.010 | / | / | Clinical Seizures I: 27 vs. C: 40 p value 0.013 | / |

| EEG seizures I: 14 vs. C: 24 p value 0.408 | ||||||

| Death or Abnormal MRI: I: 26 vs. C: 35 p value 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boscarino, G.; Esposito, S.; Terrin, G. Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in Critically Ill Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010026

Boscarino G, Esposito S, Terrin G. Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in Critically Ill Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoscarino, Giovanni, Susanna Esposito, and Gianluca Terrin. 2026. "Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in Critically Ill Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010026

APA StyleBoscarino, G., Esposito, S., & Terrin, G. (2026). Administration of Sodium Bicarbonate in Critically Ill Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010026