Three in a Bed: Can Partner Support Improve CPAP Adherence? A Systematic Review and Intervention Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

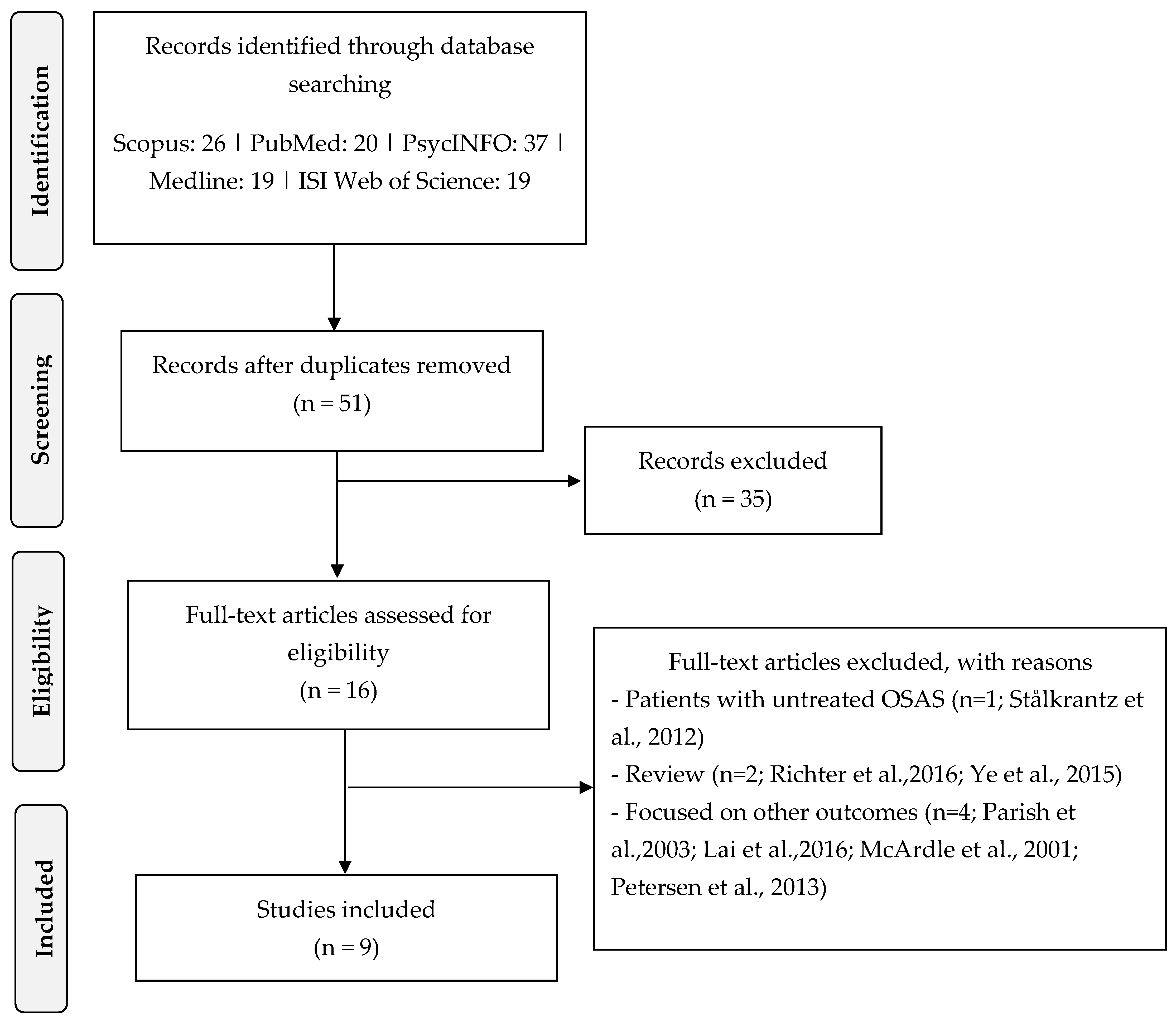

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Quality of the Included Studies: The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Description of the Sample

3.4. The Impact of Relationship Status and Co-Sleeping on CPAP Adherence

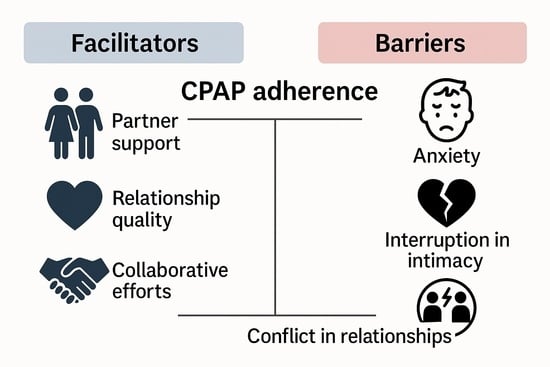

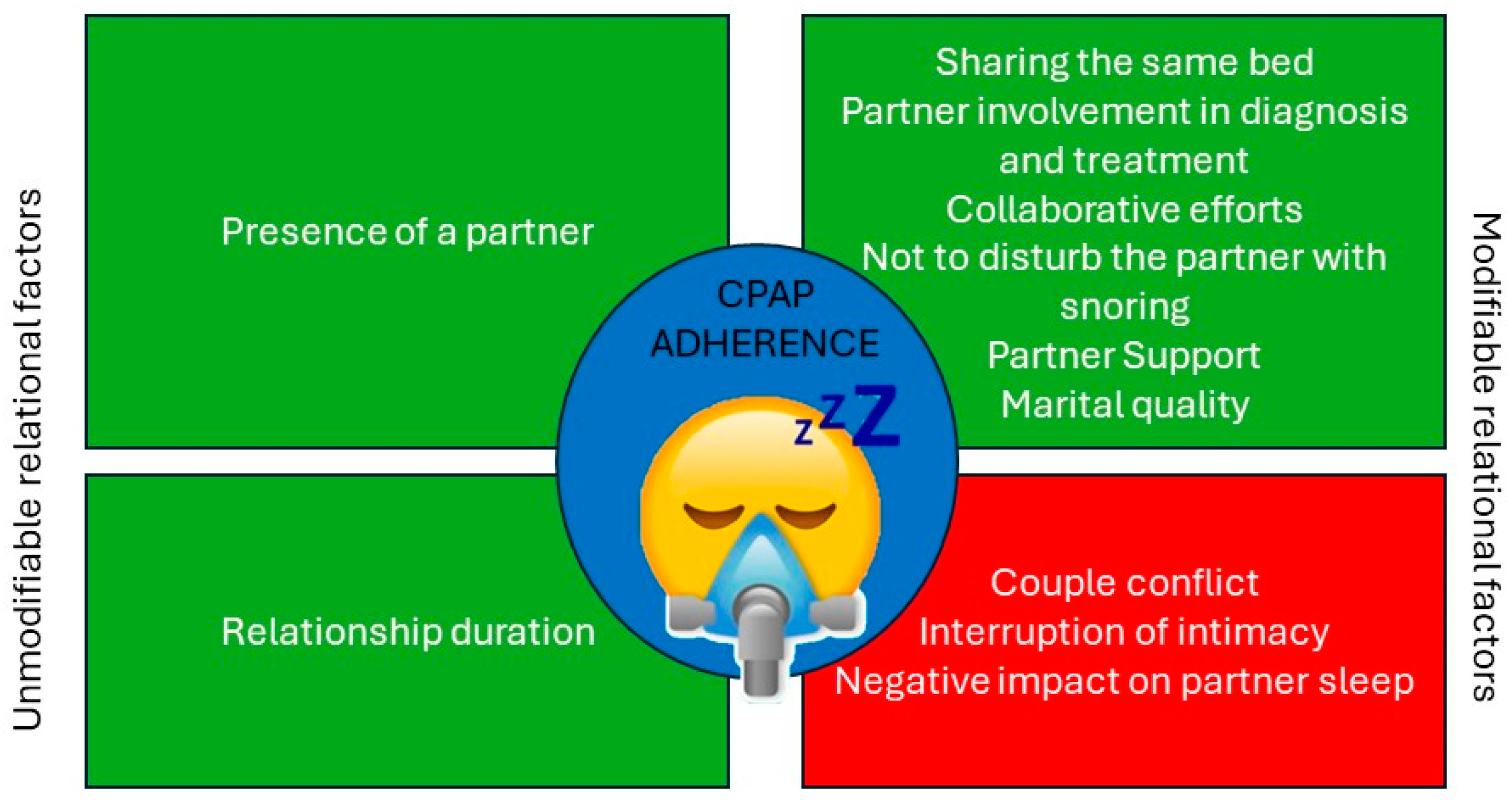

3.5. Relational Quality Influencing CPAP Adherence

3.6. Effects of Relational Variables on Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Relationship Status and Co-Sleeping

4.2. Partner Support as a Facilitator—And Sometimes a Barrier

4.3. Limitations and Strengths of This Study

4.4. Suggestion for Further Studies

4.5. Clinical Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Young, T.; Palta, M.; Dempsey, J.; Skatrud, J.; Weber, S.; Badr, S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, W.T.; Bonsignore, M.R.; B26 MC of EUCA. Sleep apnoea as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: Current evidence, basic mechanisms and research priorities. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, W.T.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, N. Sleep apnoea: A major and under-recognised public health concern. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 1269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stansbury, R.C.; Strollo, P.J. Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, E298. [Google Scholar]

- AlGhanim, N.; Comondore, V.R.; Fleetham, J.; Marra, C.A.; Ayas, N.T. The economic impact of obstructive sleep apnea. Lung 2008, 186, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, R.; Marshall, S.C.; Palayew, M.; Molnar, F.J.; Wilson, K.G.; Man-Son-Hing, M. Systematic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2006, 2, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, S.; Bardwell, W.A.; Guglielmi, O.; Chiorri, C.; Bonanni, E.; Magnavita, N. Association of anxiety and depression in obstructive sleep apnea patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Sleep Med. 2020, 18, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Rodriguez, F.; Peña-Griñan, N.; Reyes-Nuñez, N.; De la Cruz-Moron, I.; Perez-Ronchel, J.; De la Vega-Gallardo, F.; Fernandez-Palacin, A. Mortality in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea patients treated with positive airway pressure. Chest 2005, 128, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, L.; Bakker, J.P.; Cronin, J.; Yee, J.; White, D.P. Obstructive sleep apnea and obesity: A review of epidemiology, pathophysiology and the effect of weight-loss treatments. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024, 78, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, S.B.; Edwards, B.A.; Malhotra, A.; Bakker, J.P. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I.O.M.; Cunha, M.O.; Bussi, M.T.; Cassetari, A.J.; Zancanella, E.; Bagarollo, M.F. Impacts of conservative treatment on the clinical manifestations of obstructive sleep apnea—Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, E.; Badia, J.R.; Hernandez, L.; Carrasco, E.; de Pablo, J.; Fornas, C.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Montserrat, J.M. Evidence of the effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 159, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, T.L.; Lasserson, T.J.; Smith, B.; White, J.; Wright, J.J.; Cates, C.J. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 1, CD001106. [Google Scholar]

- Engleman, H.M.; Cheshire, K.E.; Deary, I.J.; Douglas, N.J. Daytime sleepiness, cognitive performance and mood after continuous positive airway pressure for the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax 1993, 48, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, S.M. Encouraging CPAP adherence: It is everyone’s job. Respir. Care. 2010, 55, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J. Long-term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in obstructive sleep apnea patients and nonapneic snorers. Sleep 1992, 15, S42–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.E.; Grunstein, R.R. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: The challenge to effective treatment. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Bakker, J.P.; Stitt, C.J.; Aloia, M.S.; Nouraie, S.M. Age and sex disparities in adherence to CPAP. Chest 2021, 159, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, M.; Bakker, J.P.; Ayas, N. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Lung 2019, 197, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennum, P.; Castro, J.C.; Mettam, S.; Kharkevitch, T.; Cambron-Mellott, M.J. Socioeconomic and humanistic burden of illness of excessive daytime sleepiness severity associated with obstructive sleep apnoea in the European Union 5. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill Pruitt, M.B.A. Top 10 Practices to Increase CPAP Compliance. Available online: https://sleepreviewmag.com/sleep-treatments/therapy-devices/cpap-pap-devices/top-10-practices-to-increase-cpap-compliance/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Nowak, C.; Bourgin, P.; Portier, F.; Genty, E.; Escourrou, P.; Bobin, S. Nasal obstruction and compliance to nasal positive airway pressure. Ann. D’oto-Laryngol. Chir. Cervico Faciale Bull. Soc. D’oto-Laryngol. Hop. Paris 2003, 120, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, D.D.; Mayers, I.; Man, G.C.W.; Pawluk, L. Long-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: A population-based study. Chest 2002, 121, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapelli, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Angeli, L.; Bastoni, I.; Tovaglieri, I.; Fanari, P.; Castelnuovo, G. Assessing the needs and perspectives of patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome following continuous positive airway pressure therapy to inform health care practice: A focus group study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 947346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broström, A.; Nilsen, P.; Johansson, P.; Ulander, M.; Strömberg, A.; Svanborg, E.; Fridlund, B. Putative facilitators and barriers for adherence to CPAP treatment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A qualitative content analysis. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyster, F.S.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Aloia, M.S.; Martire, L.M.; Buysse, D.J.; Strollo, P.J. Patient and Partner Experiences With Obstructive Sleep Apnea and CPAP Treatment: A Qualitative Analysis. Behav. Sleep Med. 2016, 14, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parish, J.M.; Lyng, P.J. Quality of life in bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 2003, 124, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapelli, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Bastoni, I.; Scarpina, F.; Tovaglieri, I.; Perger, E.; Garbarino, S.; Fanari, P.; Lombardi, C.; et al. Improving CPAP Adherence in Adults With Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Scoping Review of Motivational Interventions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 705364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, C.E.; Smith, T.W.; Baucom, B.R.; Uchino, B.N.; Williams, P.G.; Sundar, K.M.; Czajkowski, L. Relationship partner social behavior and continuous positive airway pressure adherence: The role of autonomy support. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosland, A.-M.; Heisler, M.; Choi, H.-J.; Silveira, M.J.; Piette, J.D. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2010, 6, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.E.; Seale, L.; Bartle, I.E.; Watkins, A.J.; Ebden, P. Early predictors of CPAP use for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2004, 27, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R. Sleeping together: A pilot study of the effects of shared sleeping on adherence to CPAP treatment in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2008, 4, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.S.C.; Chan, J.K.W.; Choy, D.K.L.; Ko, F.W.; Li, T.S.; Leung, R.C.; Lai, C.K. Effects of augmented continuous positive airway pressure education and support on compliance and outcome in a Chinese population. Chest 2000, 117, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Demner-Fushman, D.; American Medical Informatics Association. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2006, 2006, 359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, V.; Devane, D.; Begley, C.M.; Clarke, M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålkrantz, A.; Broström, A.; Wiberg, J.; Svanborg, E.; Malm, D. Everyday life for the spouses of patients with untreated OSA syndrome. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.; Adam, S.; Geiss, L.; Peter, L.; Niklewski, G. Two in a bed: The influence of couple sleeping and chronotypes on relationship and sleep. An overview. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.Y.K.; Ip, M.S.M.; Lam, J.C.M.; Weaver, T.E.; Fong, D.Y.T. A pathway underlying the impact of CPAP adherence on intimate relationship with bed partner in men with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2016, 20, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, N.; Kingshott, R.; Engleman, H.M.; Mackay, T.W.; Douglas, N.J. Partners of patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: Effect of CPAP treatment on sleep quality and quality of life. Thorax 2001, 56, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.; Kristensen, E.; Berg, S.; Midgren, B. Long-Term Effects of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment on Sexuality in Female Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sex Med. 2013, 1, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.C.; Skomro, R.; Wrath, A.J.; Le, T.; McWilliams, L.A.; Fenton, M.E. The relationship between attachment, treatment compliance and treatment outcomes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 137, 110196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, K.G.; Gunn, H.E.; Wolfe, L.F.; Zee, P.C. Relationships and CPAP adherence among women with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Sci. Pract. 2017, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool-Anwar, S.; Baldwin, C.; Fass, S.; Quan, S. Role of spousal involvement in continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Southwest J. Pulm. Crit. Care 2017, 14, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, T.; Bailly, S.; Jounieaux, F.; Verkindre, C.; Broussier, P.-M.; Guffroy, D.; Prigent, A.; Gres, J.-J.; Kabbani, J.; Kedziora, L.; et al. Marital quality, partner’s engagement and continuous positive airway pressure adherence in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2019, 55, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.N.S.; Todem, D.; Bottu, S.; Safwan Badr, M.; Olomu, A. Impact of patient and family engagement in improving continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.; Gentina, T.; Gentina, E.; Tamisier, R.; Pépin, J.-L.; Bailly, S. Multidimensional Evaluation of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Treatment for Sleep Apnea in Different Clusters of Couples. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramonti, F.; Maestri, M.; Carnicelli, L.; Fava, G.; Lombardi, V.; Rossi, M.; Fabbrini, M.; Di Coscio, E.; Iacopini, E.; Bonanni, E. Relationship quality of persons with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Antonelli, M.T.; Willis, D.G.; Kayser, K.; Malhotra, A.; Patel, S.R. Couples’ experiences with continuous positive airway pressure treatment: A dyadic perspective. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Malhotra, A.; Kayser, K.; Willis, D.G.; Horowitz, J.A.; Aloia, M.S.; Weaver, T.E. Spousal involvement and CPAP adherence: A dyadic perspective. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 19, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Regist. Copyr. 2018, 1148552, e039246. [Google Scholar]

- Pluye, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Johnson-Lafleur, J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tae, H.; Chae, J.-H. Factors Related to Suicide Attempts: The Roles of Childhood Abuse and Spirituality. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 565358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapelli, G.; Donato, S.; Pagani, A.F.; Parise, M.; Iafrate, R.; Pietrabissa, G.; Giusti, E.M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Bertoni, A. The association between cardiac illness-related distress and partner support: The moderating role of dyadic coping. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1992, 15, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, S.; Rudilla, D.; Pasche, H.; Zammit, D.C.; De Mercado, P.L.Y.; Rodríguez, P.L. Clinical and economic assessment of a comprehensive program to improve adherence of continuous positive airway pressure treatment in obstructive sleep apnea patients in Spain: A randomized controlled trial with a health economic model. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, OA3293. [Google Scholar]

- Rudilla, D.; Perelló, S.; Landete, P.; Zamora, E.; Vázquez, M.; Sans, L.; Tomás, J.M.; Martín, J.L.R.; Leonardi, J.; Rubinos, G.; et al. Improving adherence and quality of life of CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea with an intervention based on stratification and personalization of care plans: A randomized controlled trial. Res. Sq. 2021; preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Rapelli, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Angeli, L.; Manzoni, G.M.; Tovaglieri, I.; Perger, E.; Garbarino, S.; Fanari, P.; Lombardi, C.; Castelnuovo, G. Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing-based intervention to improve adherence to continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: The MotivAir study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 947296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazeau, H.; Lewis, N.A. Within-couple health behavior trajectories: The role of spousal support and strain. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, N.; Fisher, A.; Beeken, R.J.; Pini, S.; Miller, N.; Buck, C.; Lally, P.; Conway, R. The role of partner support for health behaviours in people living with and beyond cancer: A qualitative study. Psycho Oncol. 2022, 31, 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubert, L.; Bernardes, S.F. Interpersonal dynamics in chronic pain: The role of partner behaviors and interactions in chronic pain adjustment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2025, 62, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, H.J.; Wallot, S.; Brysch, P.; Berger-Johannsen, H.; Weinhold, S.L.; Mitkidis, P.; Baier, P.C.; Lechinger, J.; Roepstorff, A.; Göder, R. Bed-sharing in couples is associated with increased and stabilized REM sleep and sleep-stage synchronization. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, M.; Coulter, K.; Doubleday, K.; Espinoza, C.; Redondo, F.; Wilkinson-Lee, A.M.; Lohr, A.M.; Carvajal, S.C. An integrated mixed methods approach to clarifying delivery, receipt and potential benefits of CHW-facilitated social support in a health promotion intervention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martire, L.M.; Helgeson, V.S. Close relationships and the management of chronic illness: Associations and interventions. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosland, A.-M.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: A systematic review. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 35, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bertos, S.E.; Holmberg, D.; Shields, C.A.; Matheson, L.P. Partners’ attachment styles and overprotective support as predictors of patient outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation. Rehabil. Psychol. 2020, 65, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapelli, G.; Donato, S.; Bertoni, A.; Spatola, C.; Pagani, A.F.; Parise, M.; Castelnuovo, G. The combined effect of psychological and relational aspects on cardiac patient activation. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2020, 27, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, V.; Battaglia, E.; Banfi, P.; Volpato, E. Impact of illness perceptions on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) adherence and couple relationship quality in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): A cross-sectional study. Eur. Respir. J 2024, 64, PA3233. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Criterion 1 | Criterion 2 | Criterion 3 | Criterion 4 | Criterion 5 | Total ✅ | Methodological Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al., 2020 [42] | Quantitative descriptive | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | 4/5 | Acceptable/High |

| Baron et al., 2017 [43] | Quantitative descriptive | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | 4/5 | Acceptable/High |

| Batool-Anwar et al., 2017 [44] | Quantitative RCT | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | 2/5 | Low |

| Gentina et al., 2018 [45] | Quantitative descriptive | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | 4/5 | Acceptable/High |

| Khan et al., 2022 [46] | Quantitative RCT | ❓ | ❓ | ✅ | ❓ | ✅ | 2/5 | Low |

| Mendelson et al., 2020 [47] | Quantitative descriptive | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ | ✅ | 4/5 | Acceptable/High |

| Rapelli et al., 2022 [24] | Qualitative | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | 5/5 | High |

| Tramonti et al., 2017 [48] | Quantitative descriptive | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ | ✅ | 4/5 | Acceptable/High |

| Ye et al., 2017 [49] | Qualitative | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | 5/5 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rapelli, G.; Caloni, C.; Cattaneo, F.; Redaelli, M.; Cattivelli, R.; Landi, G.; Tossani, E.; Grandi, S.; Castelnuovo, G.; Pietrabissa, G. Three in a Bed: Can Partner Support Improve CPAP Adherence? A Systematic Review and Intervention Recommendations. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15050192

Rapelli G, Caloni C, Cattaneo F, Redaelli M, Cattivelli R, Landi G, Tossani E, Grandi S, Castelnuovo G, Pietrabissa G. Three in a Bed: Can Partner Support Improve CPAP Adherence? A Systematic Review and Intervention Recommendations. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(5):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15050192

Chicago/Turabian StyleRapelli, Giada, Carola Caloni, Francesca Cattaneo, Marco Redaelli, Roberto Cattivelli, Giulia Landi, Eliana Tossani, Silvana Grandi, Gianluca Castelnuovo, and Giada Pietrabissa. 2025. "Three in a Bed: Can Partner Support Improve CPAP Adherence? A Systematic Review and Intervention Recommendations" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 5: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15050192

APA StyleRapelli, G., Caloni, C., Cattaneo, F., Redaelli, M., Cattivelli, R., Landi, G., Tossani, E., Grandi, S., Castelnuovo, G., & Pietrabissa, G. (2025). Three in a Bed: Can Partner Support Improve CPAP Adherence? A Systematic Review and Intervention Recommendations. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(5), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15050192