Biopsy-Driven Synovial Pathophenotyping in RA: A New Approach to Personalized Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Synovial Biopsy Techniques

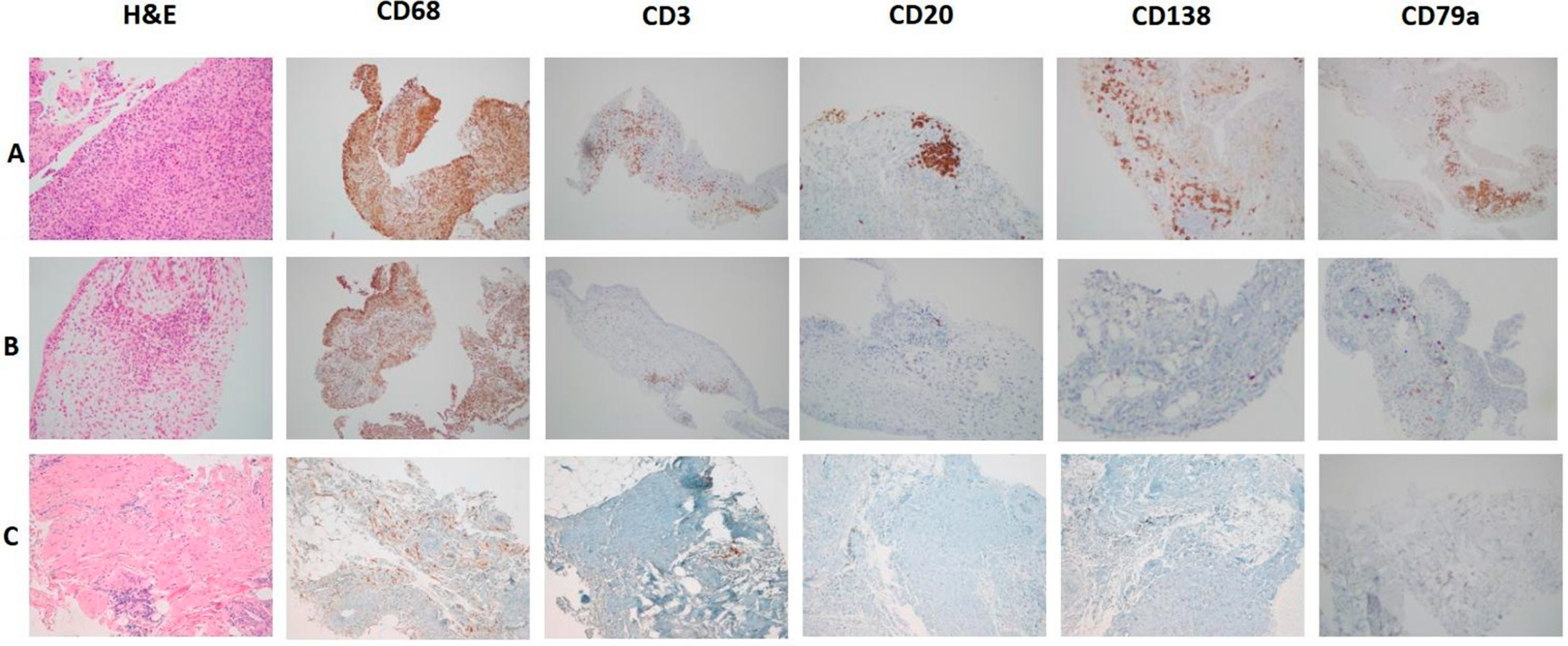

3. From Synovial Immune Cell Infiltration to Synovial Pathotype Definition

- -

- Lympho-myeloid: CD20 ≥ 2 and/or CD138 ≥ 2, with abundant CD68-sublining macrophages (≥2).

- -

- Diffuse-myeloid: CD20 ≤ 1, CD138 ≤ 1, and CD68-sublining ≥ 2, with variable CD3+ T cells.

- -

- Fibroid (pauci-immune): CD20, CD3, and CD138 < 1, with CD68 limited to the lining.

4. Synovial Pathotypes as Determinants of Treatment Response: Evidence from Clinical Trials

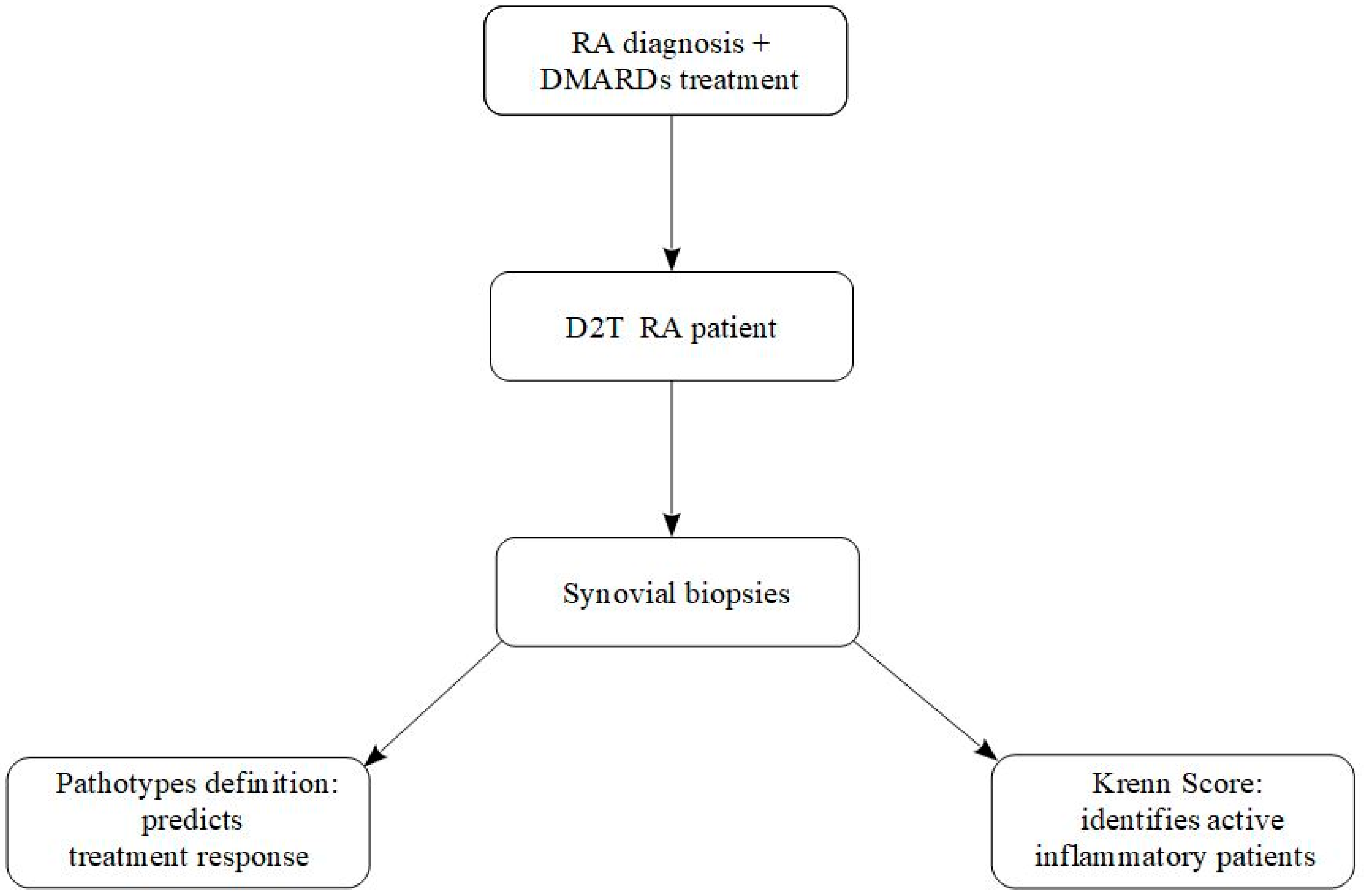

5. Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis: Definition, Challenges, and Role of Synovial Biopsy in Today’s Personalized Therapy

- (i)

- Treatment failure with ≥2 biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs (with different mechanisms of action) after inadequate response to conventional DMARDs;

- (ii)

- Presence of active/progressive disease despite these therapies;

- (iii)

- Problematic management defined by the treating rheumatologist and/or the patient [30]. This definition underscores the heterogeneity of D2T RA, which is not a synonym of refractory inflammation but rather a complex and multifactorial condition.

6. Other Emerging and Practical Applications of Synovial Biopsy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

7. Future Perspectives of Synovial Biopsy in RA

8. Conclusions

9. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, R.H.; Pearson, C.M. A simplified synovial biopsy needle. Arthritis Rheum. 1963, 6, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, H.R. Needle biopsy of the synovial membrane—Experience with the Parker–Pearson technic. N. Engl. J. Med. 1972, 286, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresnihan, B. Are synovial biopsies of diagnostic value? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003, 5, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügle, T.; Leumann, A.; Pagenstert, G.; Paul, J.; Hensel, M.; Barg, A.; Foster-Horvath, C.; Nowakowski, A.M.; Valderrabano, V.; Wiewiorski, M. Retrograde synovial biopsy of the knee joint using a novel biopsy forceps. Arthrosc. Tech. 2014, 3, e317–e319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechalekar, M.D.; Smith, M.D. Utility of arthroscopic guided synovial biopsy in understanding synovial tissue pathology in health and disease states. World J. Orthop. 2014, 5, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Humby, F.; Filer, A.; Ng, N.; Di Cicco, M.; E Hands, R.; Rocher, V.; Bombardieri, M.; A D’AGostino, M.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy: A safe, well-tolerated and reliable technique for obtaining high-quality synovial tissue from both large and small joints in early arthritis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.; Orr, C.; Heymann, M.-F.; Bart, G.; Veale, D.J.; Le Goff, B. Success Rate and Utility of Ultrasound-guided Synovial Biopsies in Clinical Practice. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, C.A.; Epis, O.; Codullo, V.; Humby, F.; Morbini, P.; Manzo, A.; Caporali, R.; Pitzalis, C.; Montecucco, C. Immunohistological assessment of the synovial tissue in small joints in rheumatoid arthritis: Validation of a minimally invasive ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy procedure. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007, 9, R101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, H.; Najm, A. Synovial biopsies in clinical practice and research: Current developments and perspectives. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humby, F.; Kelly, S.; Bugatti, S.; Manzo, A.; Filer, A.; Mahto, A.; Fonseca, J.E.; Lauwerys, B.; D’agostino, M.-A.; Naredo, E.; et al. Evaluation of Minimally Invasive, Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy Techniques by the OMERACT Filter—Determining Validation Requirements. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 43, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.; Le Goff, B.; Orr, C.; Thurlings, R.; Canete, J.D.; Humby, F.; Alivernini, S.; Manzo, A.; Just, S.A.; Romao, V.C.; et al. Standardisation of synovial biopsy analyses in rheumatic diseases: A consensus of the EULAR Synovitis and OMERACT Synovial Tissue Biopsy Groups. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najm, A.; Costantino, F.; Alivernini, S.; Alunno, A.; Bianchi, E.; Bignall, J.; Boyce, B.; Cañete, J.D.; Carubbi, F.; Durez, P.; et al. EULAR points to consider for minimal reporting requirements in synovial tissue research in rheumatology. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, I.; Largo, R.; Bong, D.A.; Filer, A.; Najm, A.; Alivernini, S.; Terslev, L.; Koski, J.; Balint, P.; Bruyn, G.A.; et al. EULAR standardised training model for ultrasound-guided, minimally invasive synovial tissue biopsy procedures in large and small joints. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzo, A.; Paoletti, S.; Carulli, M.; Blades, M.C.; Barone, F.; Yanni, G.; FitzGerald, O.; Bresnihan, B.; Caporali, R.; Montecucco, C.; et al. Systematic microanatomical analysis of CXCL13 and CCL21 in situ production and progressive lymphoid organization in rheumatoid synovitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, V.; Morawietz, L.; Burmester, G.; Kinne, R.W.; Mueller-Ladner, U.; Muller, B.; Haupl, T. Synovitis score: Discrimination between chronic low-grade and high-grade synovitis. Histopathology 2006, 49, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, V.; Morawietz, L.; Burmester, G.R.; Haupl, T. Synovialitis score: Histopathological grading system for chronic rheumatic and non-rheumatic synovialitis. Z. Rheumatol. 2005, 64, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, V.; Perino, G.; Rüther, W.; Krenn, V.; Huber, M.; Hügle, T.; Najm, A.; Müller, S.; Boettner, F.; Pessler, F.; et al. 15 years of the histopathological synovitis score, further development and review: A diagnostic score for rheumatology and orthopaedics. Pathol.-Res. Pr. 2017, 213, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humby, F.; Lewis, M.; Ramamoorthi, N.; A Hackney, J.; Barnes, M.R.; Bombardieri, M.; Setiadi, A.F.; Kelly, S.; Bene, F.; DiCicco, M.; et al. Synovial cellular and molecular signatures stratify clinical response to csDMARD therapy and predict radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, P.P.; Taylor, P.C.; Breedveld, F.C.; Smeets, T.J.M.; Daha, M.R.; Kluin, P.M.; Meinders, A.E.; Maini, R.N. Decrease in cellularity and expression of adhesion molecules by anti–tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J.E.; Shaw, K.L. Health care transition counseling for youth with arthritis: Comment on the article by Scal et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 1140–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M.C.; Jarosova, K.; Cieślak, D.; Alper, J.; Kivitz, A.; Hough, D.R.; Maes, P.; Pineda, L.; Chen, M.; Zaidi, F. Apremilast in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Phase II, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, E.H.; De Benedetti, F.; Takeuchi, T.; Hashizume, M.; John, M.R.; Kishimoto, T. Translating IL-6 biology into effective treatments. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humby, F.; Durez, P.; Buch, M.H.; Lewis, M.J.; Rizvi, H.; Rivellese, F.; Nerviani, A.; Giorli, G.; Mahto, A.; Montecucco, C.; et al. Rituximab versus tocilizumab in anti-TNF inadequate responder patients with rheumatoid arthritis (R4RA): 16-week outcomes of a stratified, biopsy-driven, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivellese, F.; Surace, A.E.A.; Goldmann, K.; Sciacca, E.; Çubuk, C.; Giorli, G.; John, C.R.; Nerviani, A.; Fossati-Jimack, L.; Thorborn, G.; et al. Rituximab versus tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis: Synovial biopsy-based biomarker analysis of the phase 4 R4RA randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivellese, F.; Nerviani, A.; Giorli, G.; Warren, L.; Jaworska, E.; Bombardieri, M.; Lewis, M.J.; Humby, F.; Pratt, A.G.; Filer, A.; et al. Stratification of biological therapies by pathobiology in biologic-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis (STRAP and STRAP-EU): Two parallel, open-label, biopsy-driven, randomised trials. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e648–e659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.J.; Çubuk, C.; Surace, A.E.A.; Sciacca, E.; Lau, R.; Goldmann, K.; Giorli, G.; Fossati-Jimack, L.; Nerviani, A.; Rivellese, F.; et al. Deep molecular profiling of synovial biopsies in the STRAP trial identifies signatures predictive of treatment response to biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi, F.; Slowikowski, K.; Wei, K.; Marshall, J.L.; Rao, D.A.; Chang, S.K.; Nguyen, H.N.; Noss, E.H.; Turner, J.D.; Earp, B.E.; et al. Functionally distinct disease-associated fibroblast subsets in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Slowikowski, K.; Fonseka, C.Y.; Rao, D.A.; Kelly, S.; Goodman, S.M.; Tabechian, D.; Hughes, L.B.; Salomon-Escoto, K.; et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret, F.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Lafeber, F.P.J.G.; van Roon, J.A.G. The efficacy of abatacept in reducing synovial T cell activation by CD1c myeloid dendritic cells is overruled by the stimulatory effects of T cell-activating cytokines. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 67, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; Welsing, P.M.; Kedves, M.; Hamar, A.; van der Goes, M.C.; Kent, A.; Bakkers, M.; Blaas, E.; Senolt, L.; et al. EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Sepriano, A.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; de Wit, M.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anno, S.; Okano, T.; Mamoto, K.; Yamada, Y.; Mandai, K.; Orita, K.; Iida, T.; Tada, M.; Inui, K.; Koike, T.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2024, 35, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Z.; Bartelo, N.; Aslam, M.; Murphy, E.A.; Hale, C.R.; Blachere, N.E.; Parveen, S.; Spolaore, E.; DiCarlo, E.; Gravallese, E.M.; et al. Synovial Fibroblast Gene Expression is Associated with Sensory Nerve Growth and Pain in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadk3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giollo, A.; Salvato, M.; Frizzera, F.; Khalid, K.; Di Luozzo, L.; Capita, M.; Garaffoni, C.; Lanza, G.; Fedrigo, M.; Angelini, A.; et al. Clinical application of synovial biopsy in non-inflammatory and persistent inflammatory refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025. In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, J.; Delrosso, C.A.; Nerviani, A.; Pitzalis, C. Clinical Phenotypes, Serological Biomarkers, and Synovial Features Defining Seropositive and Seronegative Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Literature Review. Cells 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, M.; Wu, R. Immunophenotypic Landscape of synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis: Insights from ACPA status. Helyon 2024, 10, e34088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Long, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, R. Synovial macrophages drive severe joint destruction in established rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, G.; Firestein, G.S. Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-P.; Ma, J.-D.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Jing, J.; Zheng, D.-H.; Chen, L.-F.; Wu, T.; Chen, C.-T.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, Y.-Y.; et al. Addition of Fibroblast-Stromal Cell Markers to Immune Synovium Pathotypes Better Predicts Radiographic Progression at 1 Year in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 778480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Precision Medicine Across the Disease Continuum (PRECIS). Identifier: NCT. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04482335 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- 3TR Consortium. Pathobiology-Driven Precision Therapy in RA (3TR Precis-The-RA). Project Description. Available online: https://3tr-imi.eu (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Ren, X.; Geng, M.; Xu, K.; Lu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Kong, L.; Cai, Y.; Hou, W.; Lu, Y.; Aihaiti, Y.; et al. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Synovial Tissue Reveals That Upregulated OLFM4 Aggravates Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 4746–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, E.M.; Nteak, S.K.; van Rijswijck, D.M.; Damen, J.M.A.; Scherer, H.U.; Toes, R.E.; Bondt, A.; Huizinga, T.W.; Heck, A.J. Multitiered Proteome Analysis Displays the Hyperpermeability of the Rheumatoid Synovial Compartment for Plasma Proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2024, 24, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchereau, R.; Hong, S.; Cantarel, B.; Baldwin, N.; Baisch, J.; Edens, M.; Cepika, A.-M.; Acs, P.; Turner, J.; Anguiano, E.; et al. Personalized immunomonitoring uncovers molecular networks that stratify lupus patients. Cell 2016, 165, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathotype/Cell Program | R4RA (Bulk RNA-Seq) | STRAP (Bulk + Single-Cell RNA-Seq) | Associated Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| B cell/Lymphoid | Enrichment of immunoglobulin transcripts, CXCL13, germinal center genes | CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL13 enriched in B cell and Tfh-like clusters | Predictive of rituximab response |

| Myeloid/IL-6-driven | Upregulation of SOCS3, STAT3 targets, IL1B, CCL2 | Myeloid clusters with IL-6-responsive genes (STAT3, CCL2, IL1B) | Predictive of tocilizumab response |

| Stromal/Fibroblast | Fibroblast and ECM-related programs (HOX genes, collagens, matrix remodeling) | Fibroblast subsets enriched in ECM and developmental genes (HOX, COL1A1, COL3A1) | Associated with multidrug resistance |

| General immune activation | Downregulation of interferon and chemokine genes (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL13) in responders | Confirmed in both B cell and myeloid subsets at single-cell resolution | Common pathway of therapeutic sensitivity |

| Domain | Key Findings | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Mechanisms |

| Distinguishes inflammatory vs. neurogenic pain; avoids unnecessary immunosuppression; explains persistent pain in D2T RA. |

| Early/Undifferentiated Synovitis |

| Helps identify patients at high risk of developing definite RA; supports early intervention strategies. |

| ACPA-Positive vs. ACPA-Negative RA |

| Confirms biologically distinct endotypes; explains therapeutic differences; refines serological stratification using tissue data. |

| Erosive Bone Damage |

| Supports use of biopsy for structural prognosis; identifies high-risk erosive phenotype; complements imaging. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ketabchi, S.; Russo, E.; Benucci, M.; Infantino, M.; Manfredi, M.; Cassarà, E.A.M.; Li Gobbi, F.; Mannoni, A.; Terenzi, R. Biopsy-Driven Synovial Pathophenotyping in RA: A New Approach to Personalized Treatment. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120622

Ketabchi S, Russo E, Benucci M, Infantino M, Manfredi M, Cassarà EAM, Li Gobbi F, Mannoni A, Terenzi R. Biopsy-Driven Synovial Pathophenotyping in RA: A New Approach to Personalized Treatment. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):622. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120622

Chicago/Turabian StyleKetabchi, Sheyda, Edda Russo, Maurizio Benucci, Maria Infantino, Mariangela Manfredi, Emanuele Antonio Maria Cassarà, Francesca Li Gobbi, Alessandro Mannoni, and Riccardo Terenzi. 2025. "Biopsy-Driven Synovial Pathophenotyping in RA: A New Approach to Personalized Treatment" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120622

APA StyleKetabchi, S., Russo, E., Benucci, M., Infantino, M., Manfredi, M., Cassarà, E. A. M., Li Gobbi, F., Mannoni, A., & Terenzi, R. (2025). Biopsy-Driven Synovial Pathophenotyping in RA: A New Approach to Personalized Treatment. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120622