The CanCURE Survey: Gender-Based Differences in HIV Cure Research Priorities

Abstract

1. Introduction

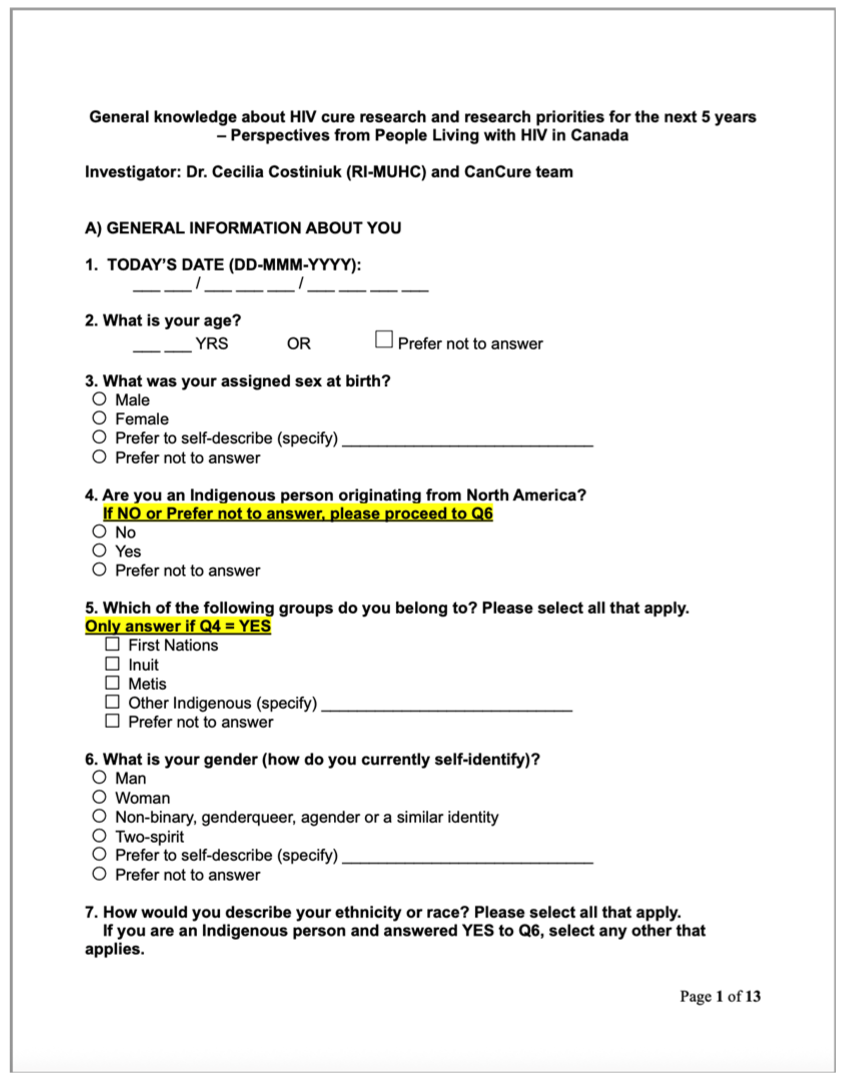

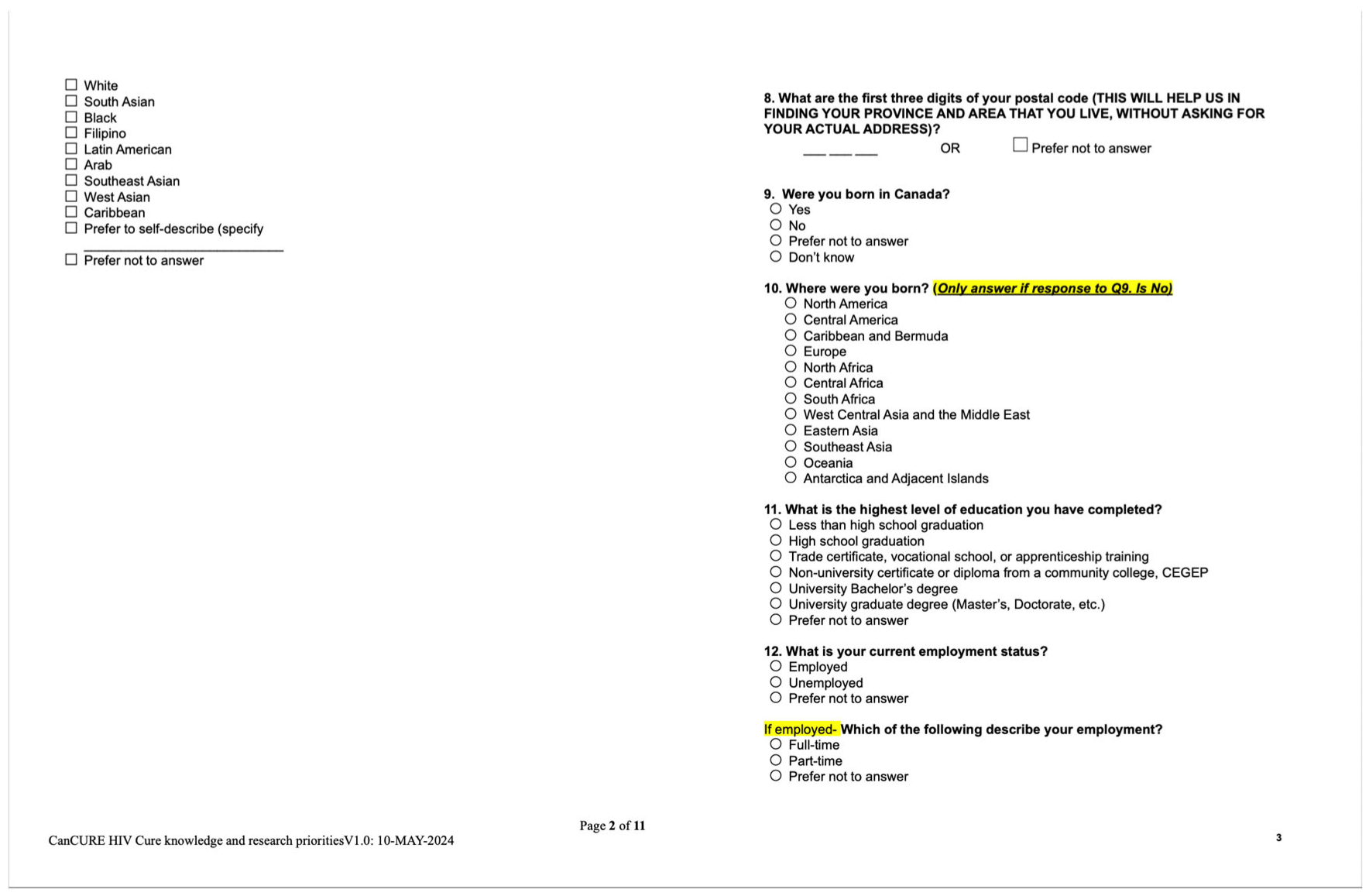

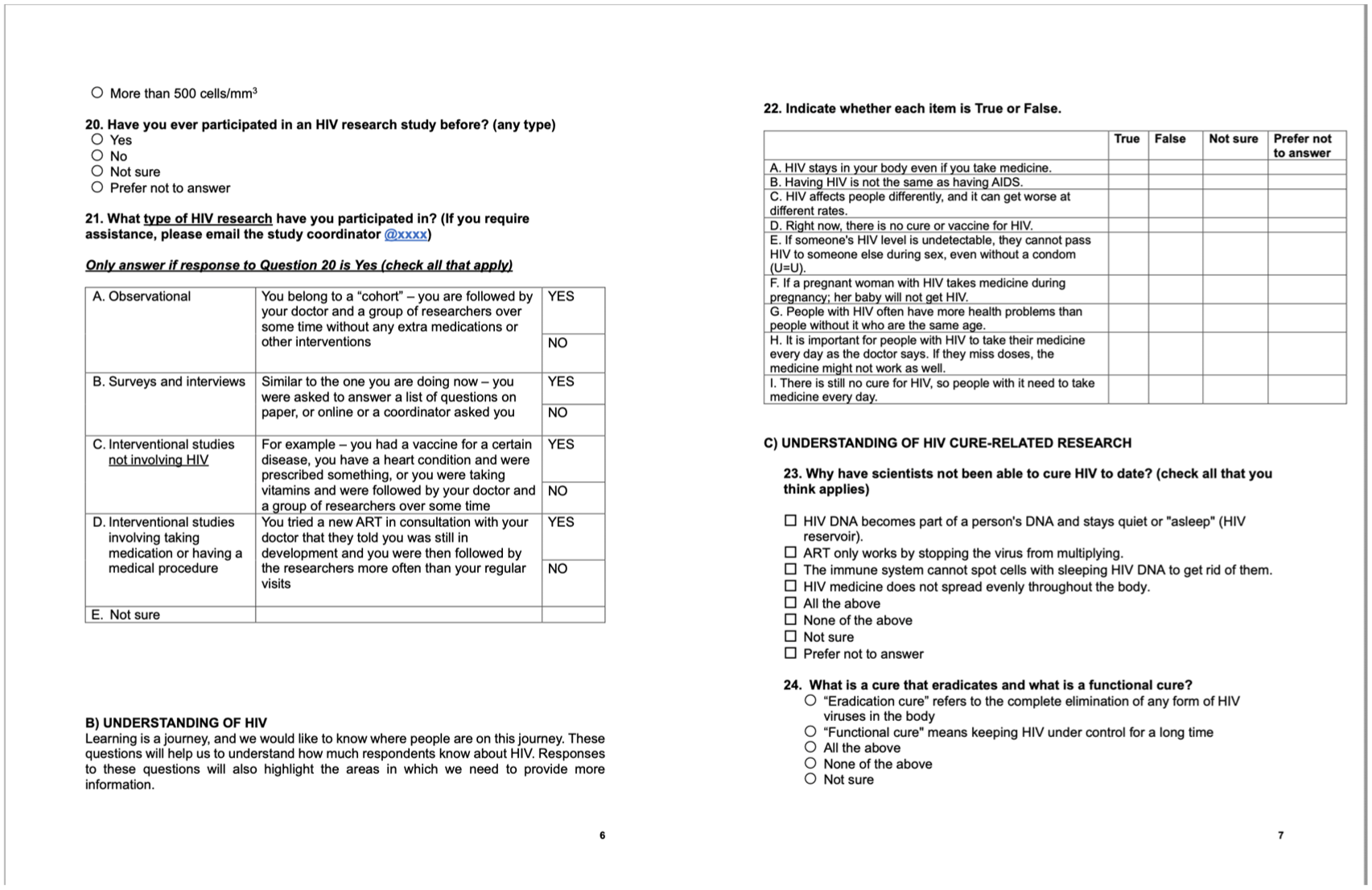

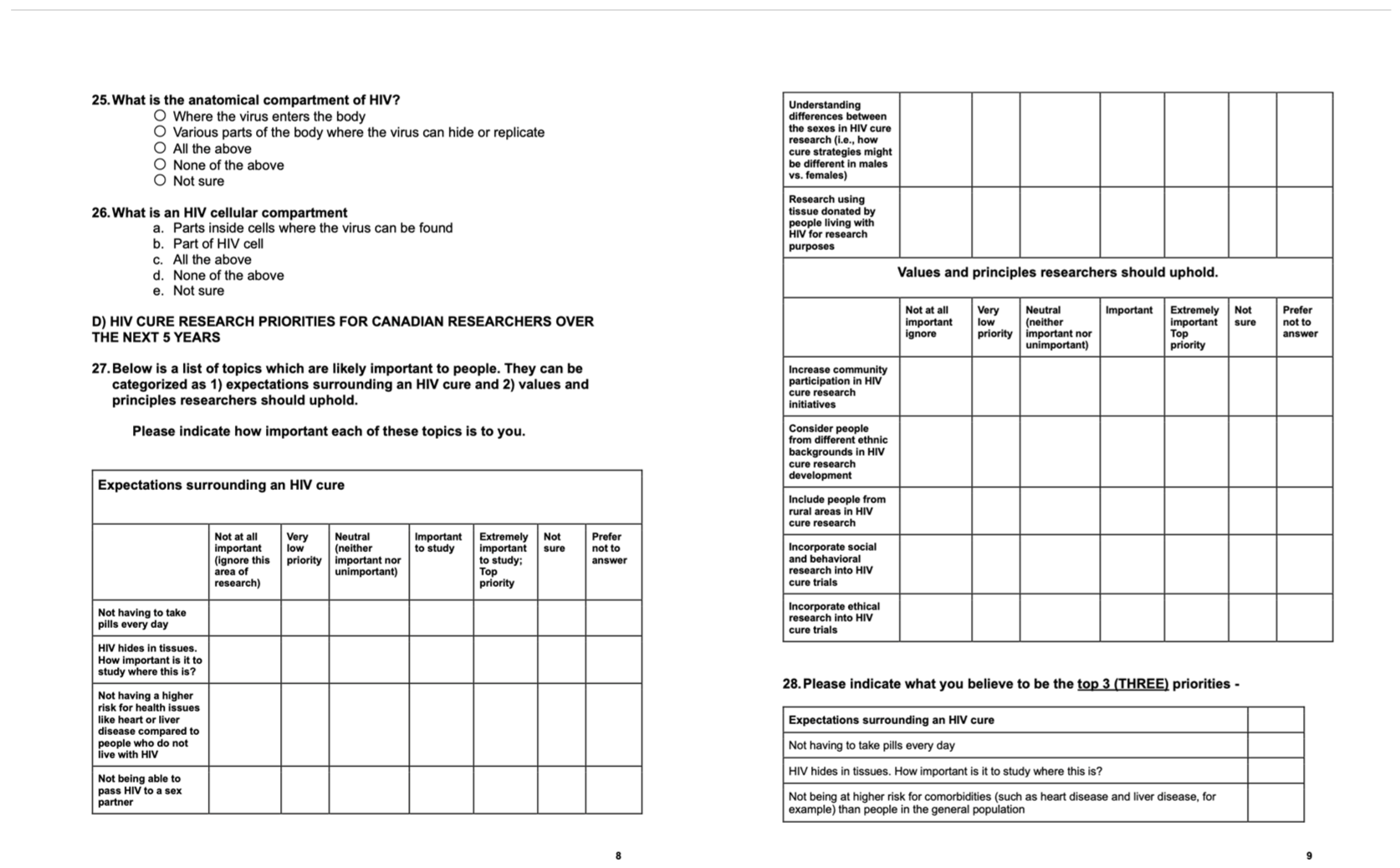

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the Survey

2.2. Participants and Recruitment Strategy

2.3. Survey Instrument

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

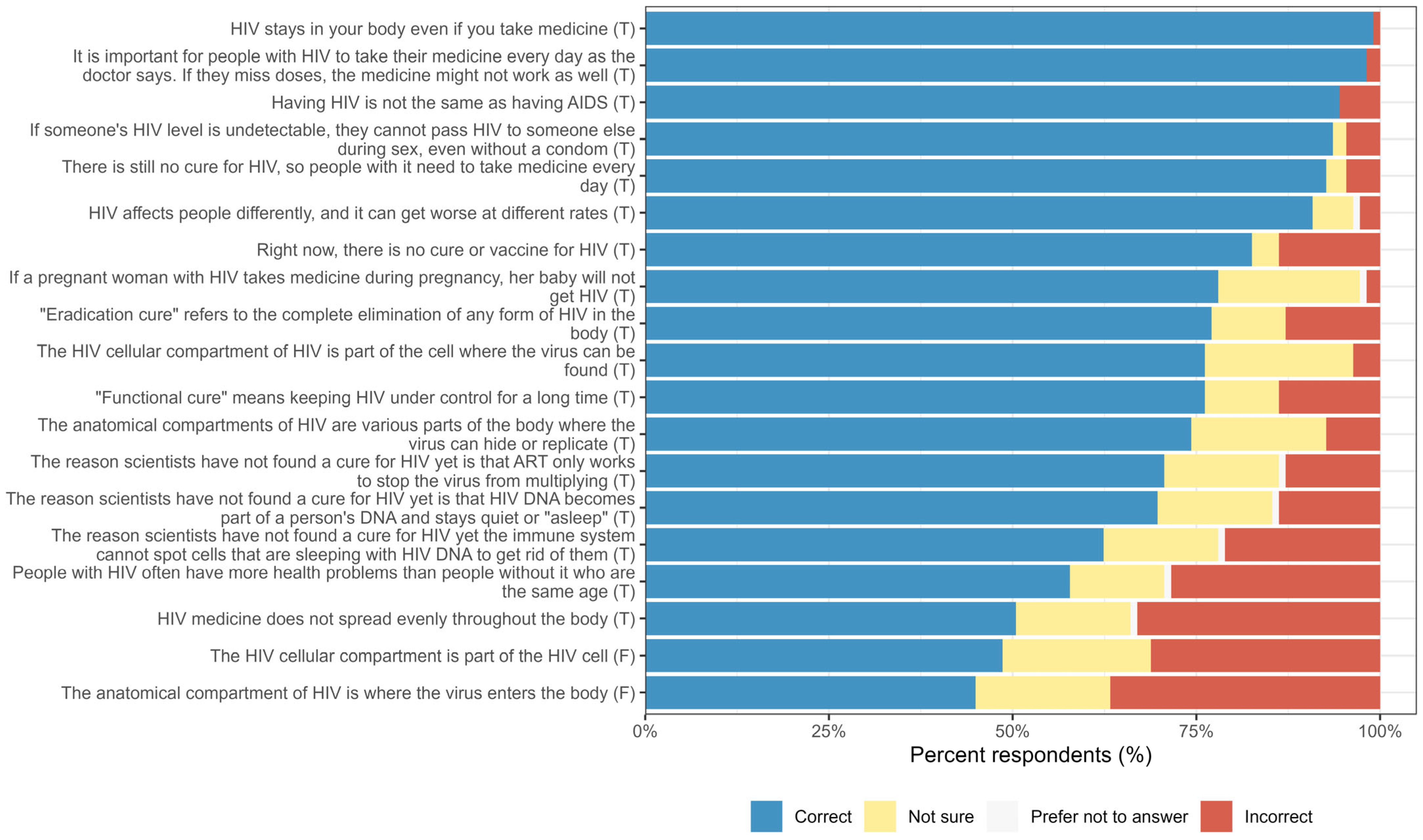

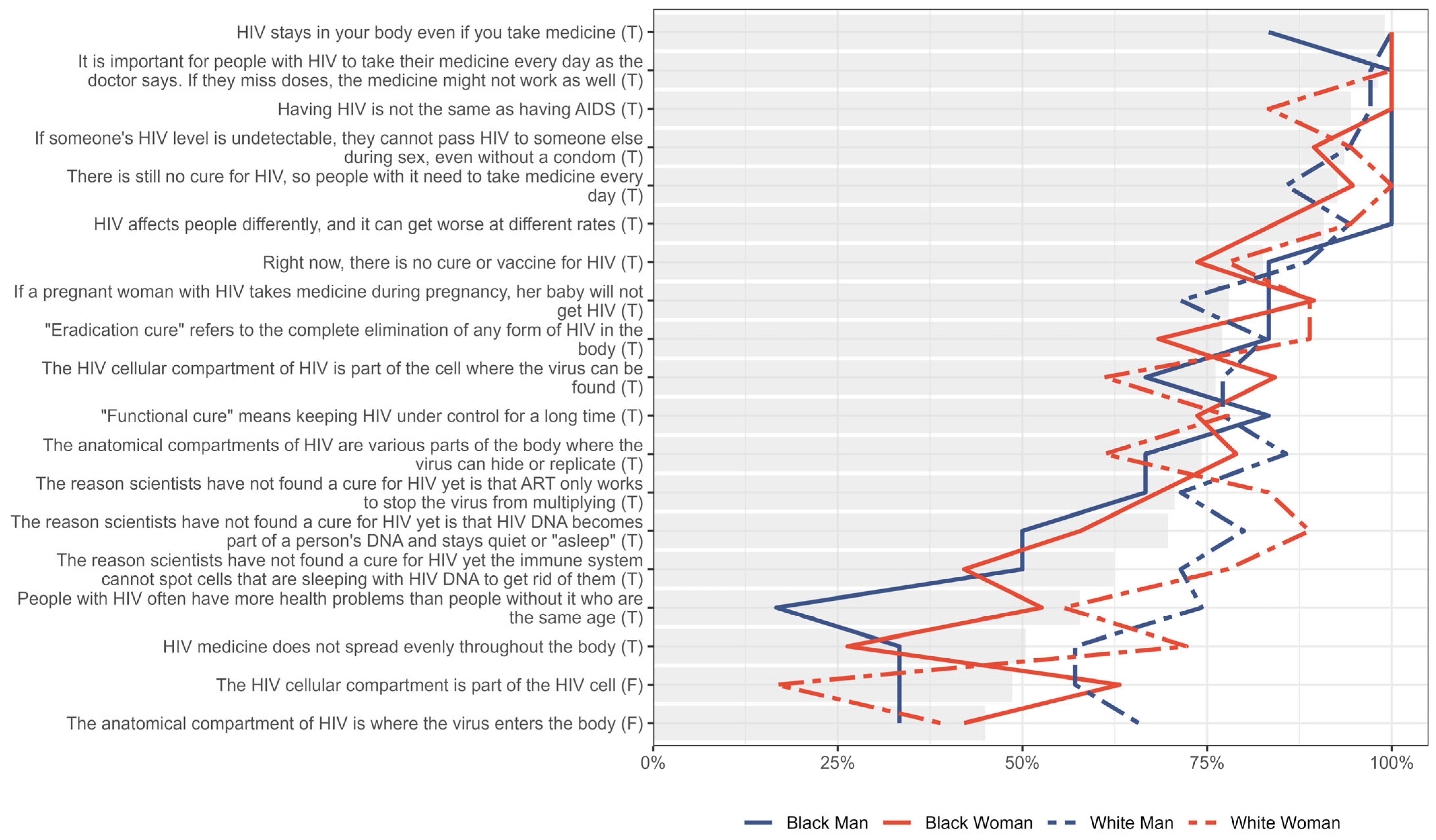

3.2. Knowledge About HIV and Cure-Related Concepts

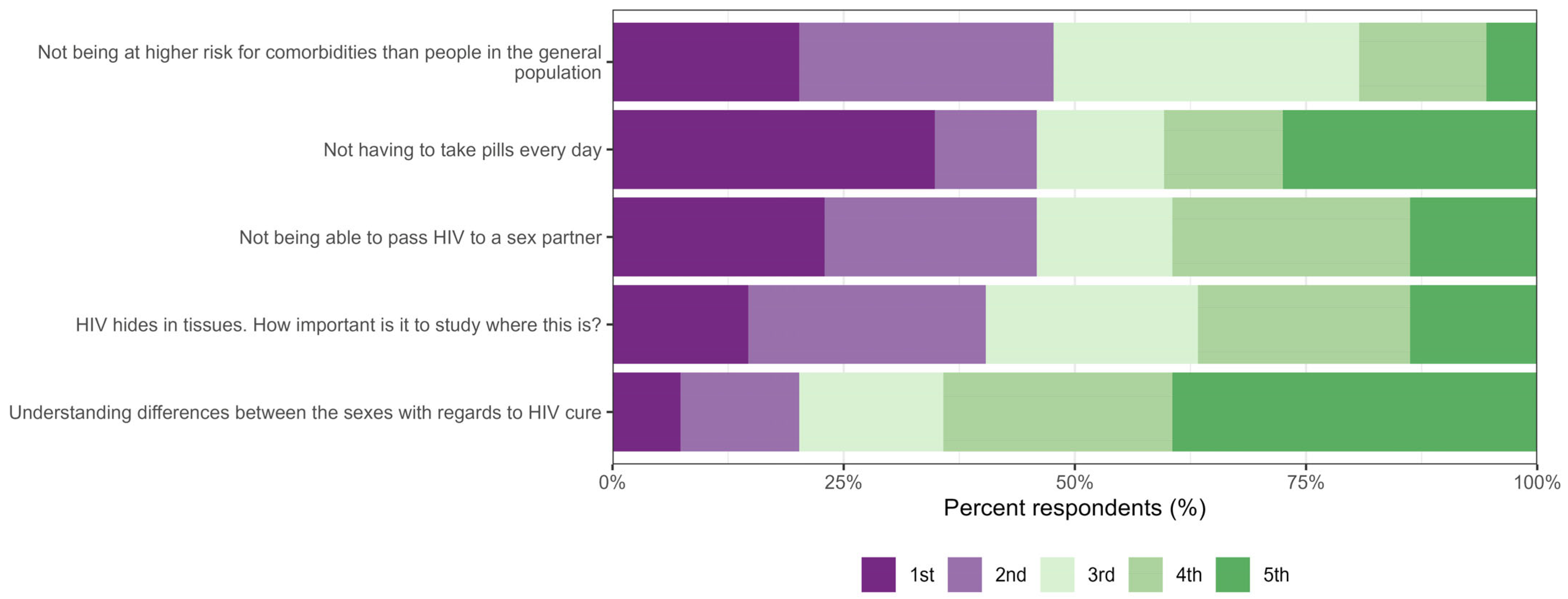

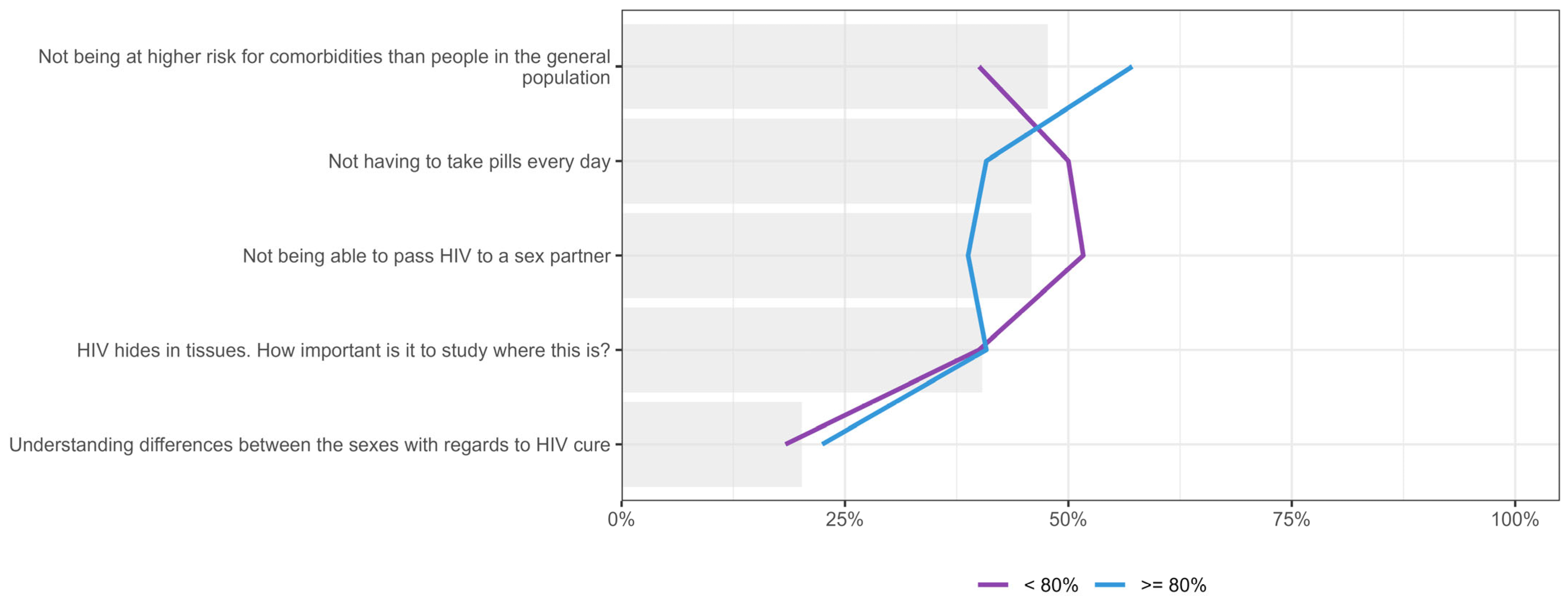

3.3. Expectations

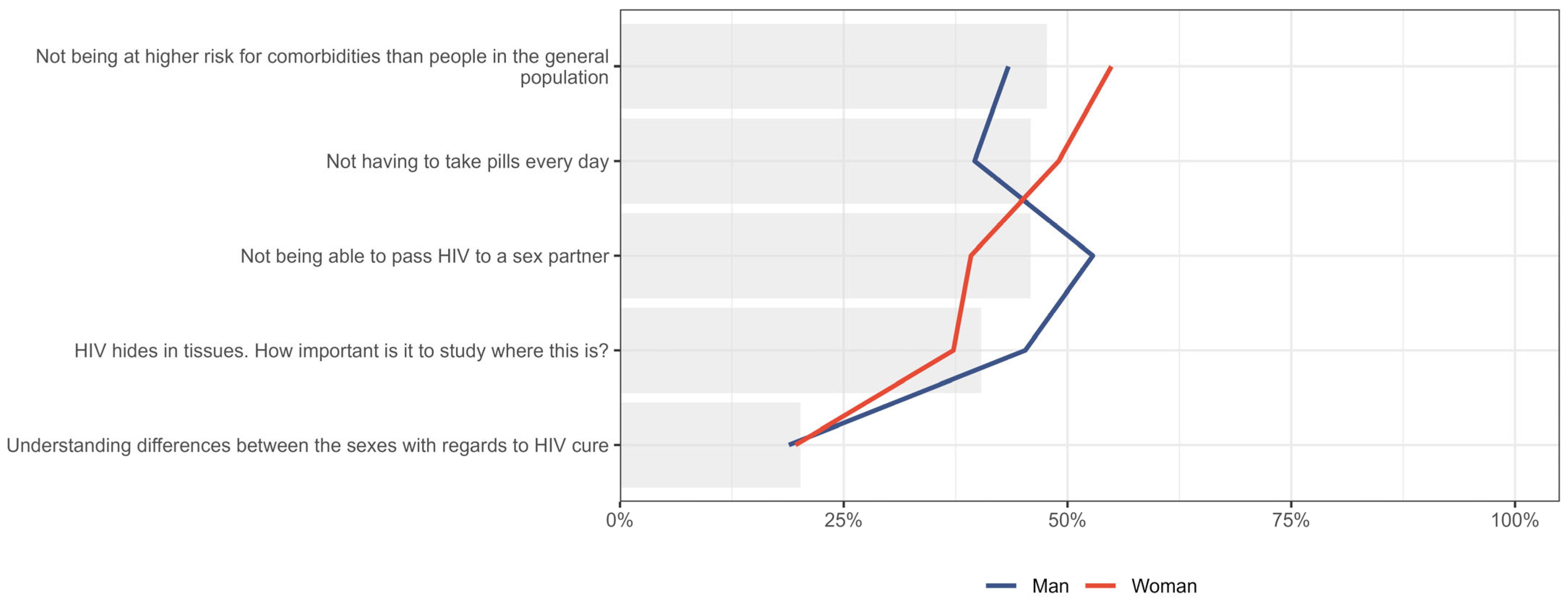

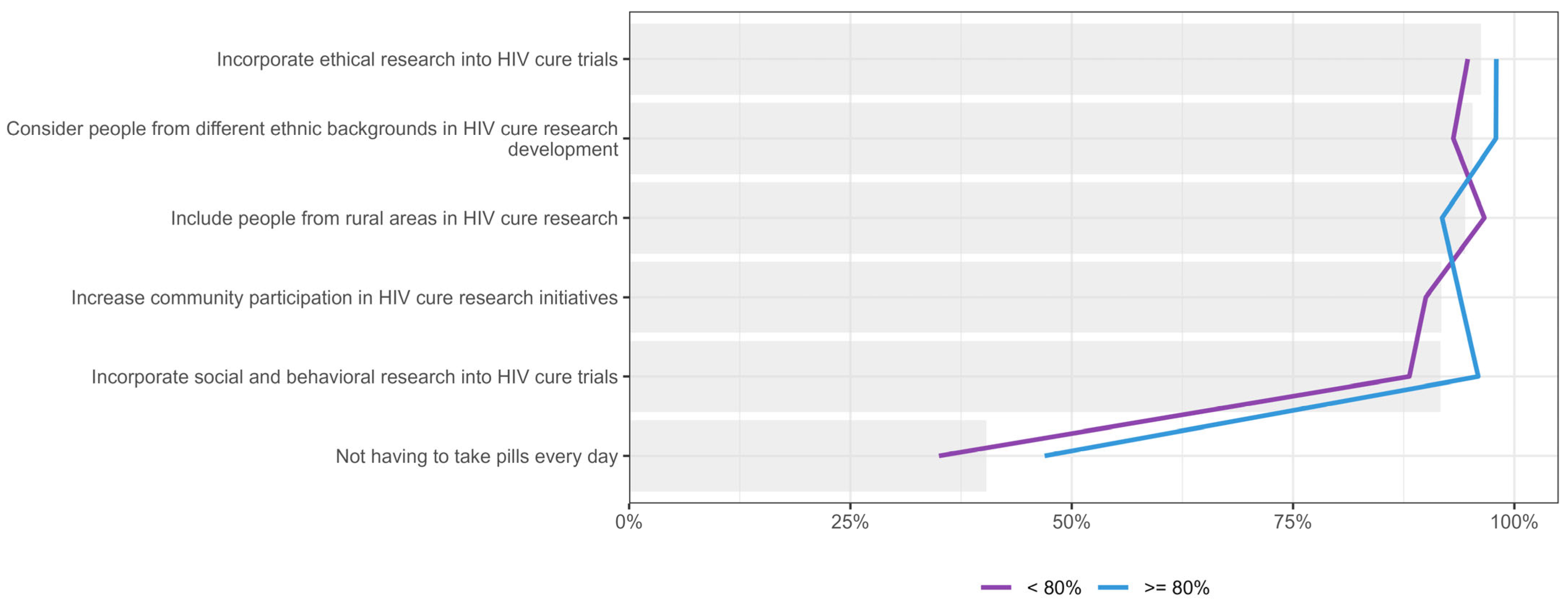

3.4. Values and Principles

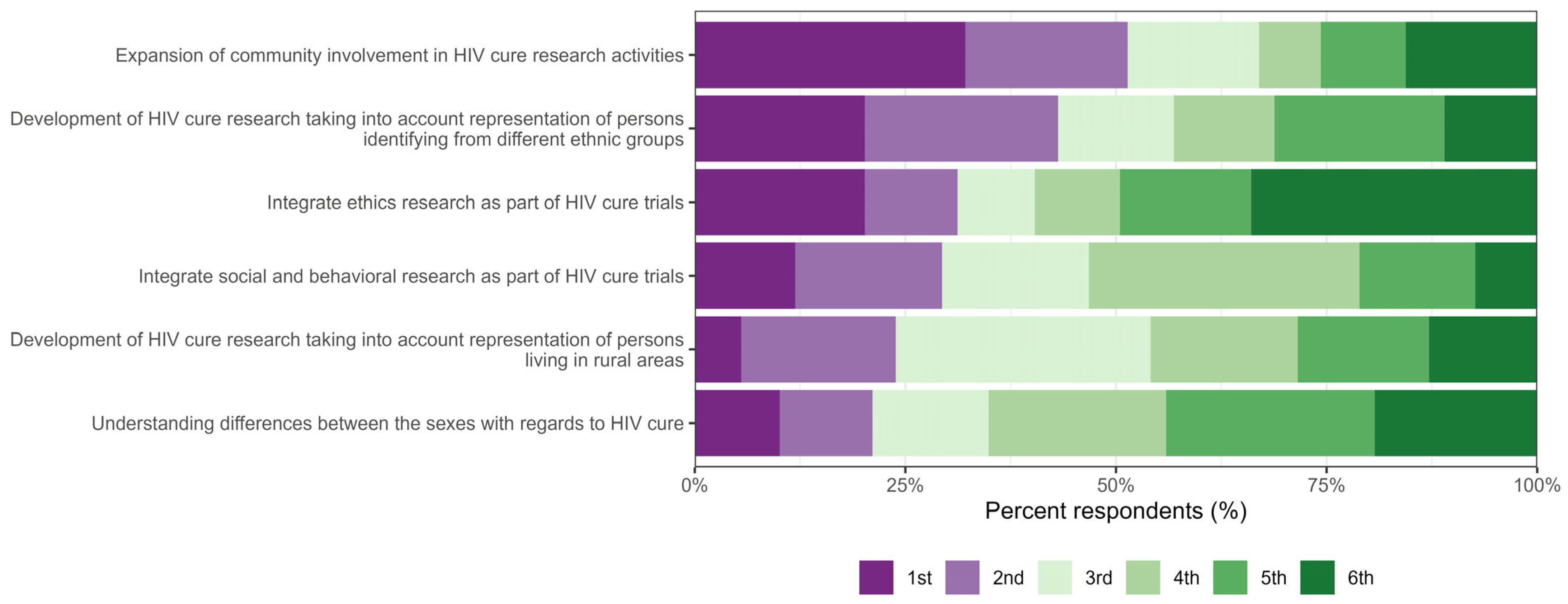

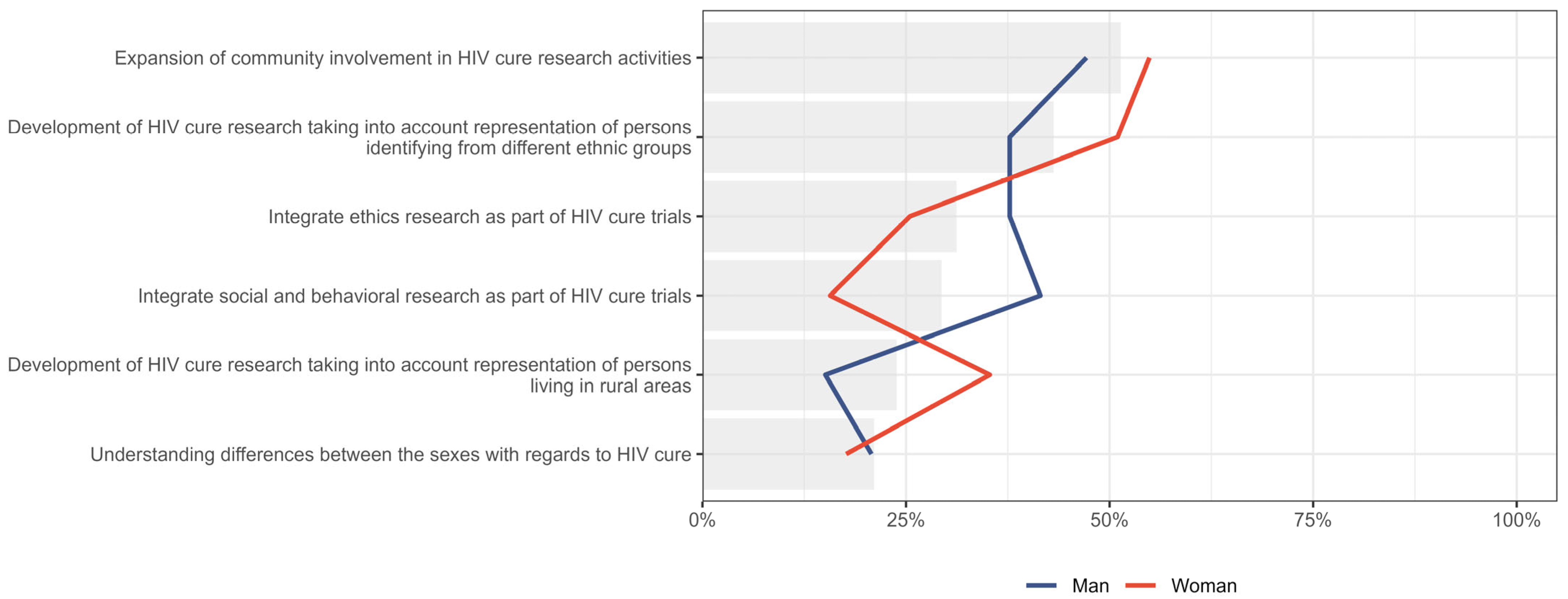

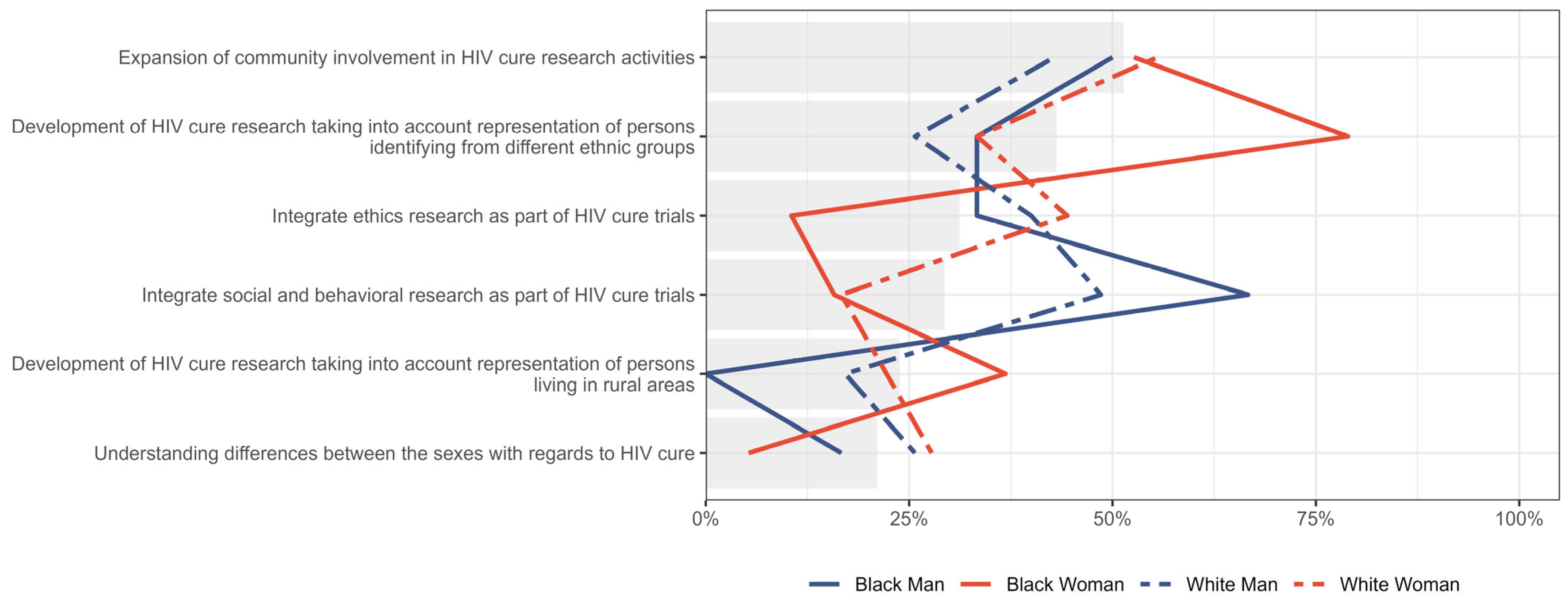

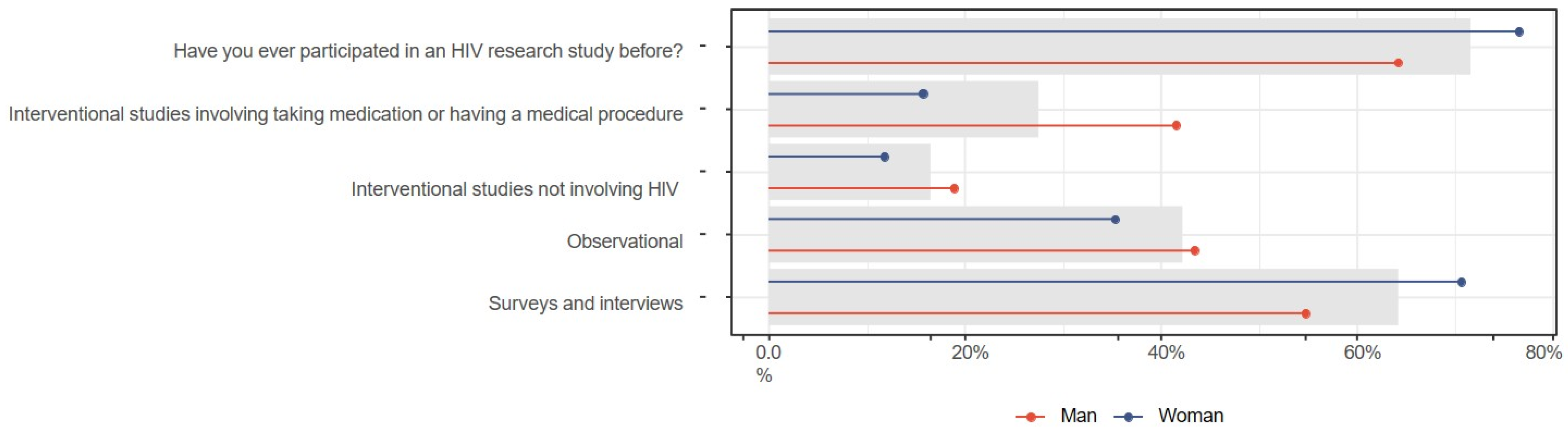

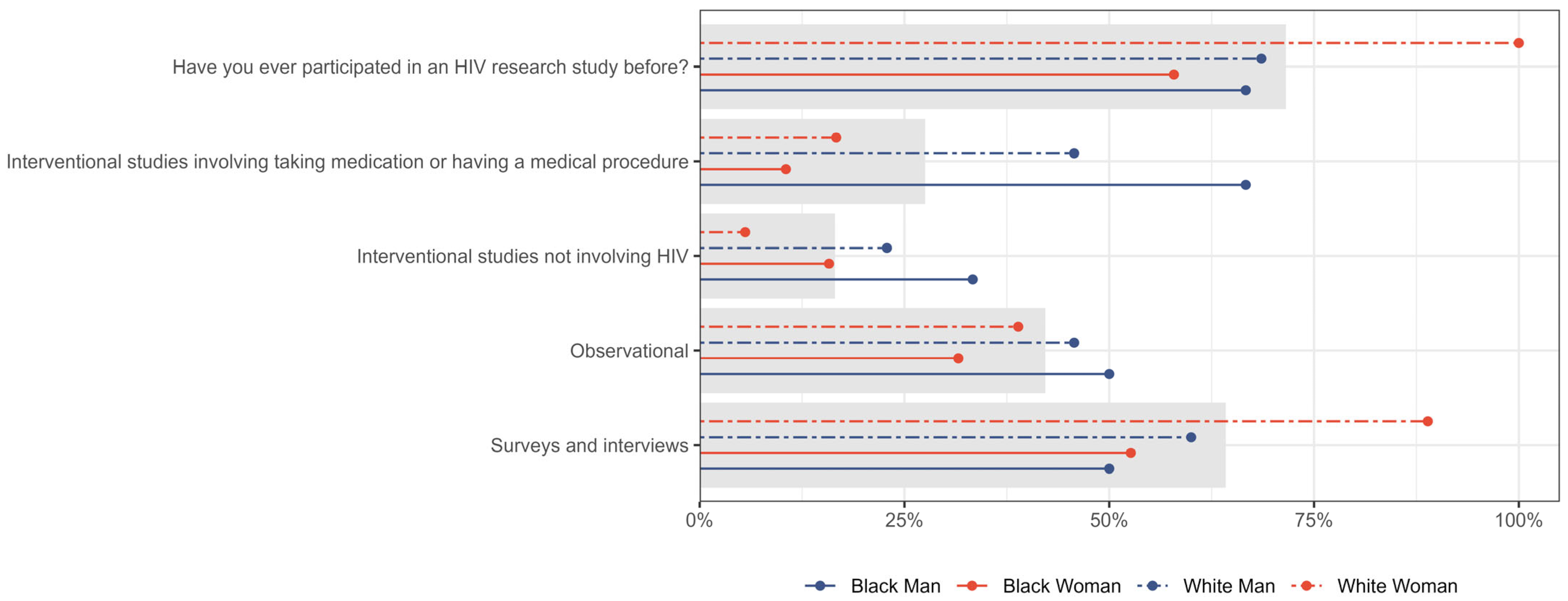

3.5. Study Participation

3.6. Expectation for an HIV Cure Stratified by Knowledge About HIV and HIV Research

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge About HIV and Cure-Related Concepts

4.2. Expectations

4.3. Values and Principles

4.4. Study Participation

4.5. How to Guide Future Research

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CanCURE | Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise |

| CAB | Community Advisory Board |

| PWH | People with HIV |

| ART | Antiretroviral Therapy |

| WWH | Women with HIV |

| MWH | Men with HIV |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Hamilton, W.L.; Aliyu, S.H. The changing landscape of HIV epidemiology and management. Clin. Med. 2025, 25, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauci, A.S. HIV and AIDS: 20 years of science. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, A.-D.; Yang, Y.; Lu, J.; Xu, Y.; Ji, X.; Wu, L.; Han, L.; Zhu, B.; Xu, M. Global, regional and national burden of HIV/AIDS among individuals aged 15–79 from 1990 to 2021. AIDS Res. Ther. 2025, 22, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łupina, K.; Nowak, K.; Lorek, D.; Nowak, A.; Romac, A.; Głowacka, E.; Janczura, J. Pharmacological advances in HIV treatment: From ART to long-acting injectable therapies. Arch. Virol. 2025, 170, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayan, M.U.; Sillman, B.; Hasan, M.; Deodhar, S.; Das, S.; Sultana, A.; Le, N.T.H.; Soriano, V.; Edagwa, B.; Gendelman, H.E. Advances in long-acting slow effective release antiretroviral therapies for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 200, 115009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, A.M.; Kufel, W.D.; Dwyer, K.A.M.; Sidman, E.F. Lenacapavir: A novel injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 63, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianella, S.; Tsibris, A.; Barr, L.; Godfrey, C. Barriers to a cure for HIV in women. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016, 19, 20706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, K.; Willenberg, L.; Dee, L.; Sylla, L.; Taylor, J.; Roebuck, C.; Palm, D.; Campbell, D.; Newton, L.; Patel, H.; et al. Re-examining the HIV ‘functional cure’ oxymoron: Time for precise terminology? J. Virus Erad. 2020, 6, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijnders, K.A.; de Groot, L.; Vervoort, S.C.; Basten, M.G.; van Welzen, B.J.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Reiss, P.; Davidovich, U.; Rozhnova, G. The perceived impact of an HIV cure by people living with HIV and key populations vulnerable to HIV in the Netherlands: A qualitative study. J. Virus Erad. 2022, 8, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Dowsett, G.W.; Westle, A.; Tucker, J.D.; Hill, S.; Sugarman, J.; Lewin, S.R.; Brown, G.; Lucke, J. The significance and expectations of HIV cure research among people living with HIV in Australia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liu, Y.; Lai, Y. Knowledge From London and Berlin: Finding Threads to a Functional HIV Cure. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 688747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananworanich, J.; Robb, M.L. The transient HIV remission in the Mississippi baby: Why is this good news? J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 19859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilg, N.; Li, J.Z. On the Road to a HIV Cure: Moving Beyond Berlin and London. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 33, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climent, N.; Ambrosioni, J.; González, T.; Xufré, C.; Casadellà, M.; Noguera-Julian, M.; Paredes, R.; Plana, M.; Grau-Expósito, J.; Mallolas, J.; et al. Immunological and virological findings in a patient with exceptional post-treatment control: A case report. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e42–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canada’s Progress Towards Ending the HIV Epidemic, 2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/canada-progress-towards-ending-hiv-epidemic-2022.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Kaufman, M.R.; Eschliman, E.L.; Karver, T.S. Differentiating sex and gender in health research to achieve gender equity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S. Sex differences in HIV-1 persistence and the implications for a cure. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 942345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ethnicity Reporting for AIDS and HIV in Canada HIV/AIDS Epi Update Ottawa: Division of HIV/AIDS Epidemiology and Surveillance; H.C. Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. HIV/AIDS Among Aboriginal Persons in Canada: A Continuing Concern HIV/AIDS Epi Update Ottawa: Division of HIV/AIDS Epidemiology and Surveillance; H.C. Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tharao, E.M.N.; Teclom, S. Silent Voices of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: African and Caribbean Women in Toronto 2002–2004; Women’s Health in Women’s Hands Community Health Centre: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orser, L.; Musten, A.; Newman, H.; Bannerman, M.; Haines, M.; Lindsay, J.; O’Byrne, P. HIV self-testing in cis women in Canada: The GetaKit study. Women’s Health 2025, 21, 17455057251322810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benning, L.; Mantsios, A.; Kerrigan, D.; Coleman, J.S.; Golub, E.; Blackstock, O.; Konkle-Parker, D.; Philbin, M.; Sheth, A.; Adimora, A.A.; et al. Examining adherence barriers among women with HIV to tailor outreach for long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P.; Warren, L.; Kazemi, M.; Massaquoi, N.; Smith, S.; Tharao, W.; Serghides, L.; Logie, C.H.; Kroch, A.; Burchell, A.N.; et al. HIV care cascade for women living with HIV in the Greater Toronto Area versus the rest of Ontario and Canada. Int. J. STD AIDS 2023, 34, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkerian, G.; Kestler, M.; Carter, A.; Wang, L.; Kronfli, N.; Sereda, P.; Roth, E.; Milloy, M.-J.; Pick, N.; Money, D.; et al. Attrition Across the HIV Cascade of Care Among a Diverse Cohort of Women Living with HIV in Canada. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 79, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curno, M.J.; Rossi, S.; Hodges-Mameletzis, I.; Johnston, R.; Price, M.A.; Heidari, S. A Systematic Review of the Inclusion (or Exclusion) of Women in HIV Research: From Clinical Studies of Antiretrovirals and Vaccines to Cure Strategies. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 71, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, K.; Coe, K.; Bailar, J.C.; Swanson, G.M. Inclusion of minorities and women in cancer clinical trials, a decade later: Have we improved? Cancer 2013, 119, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, P.S.; McNaghten, A.D.; Begley, E.; Hutchinson, A.; Cargill, V.A. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2007, 99, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coakley, M.; Fadiran, E.O.; Parrish, L.J.; Griffith, R.A.; Weiss, E.; Carter, C. Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials: Successful strategies for engaging women and minorities in clinical trials. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, K.; Barr, E.; Philbin, M.; Perez-Brumer, A.; Minalga, B.; Peterson, B.; Averitt, D.; Picou, B.; Martel, K.; Chung, C.; et al. Increasing the meaningful involvement of women in HIV cure-related research: A qualitative interview study in the United States. HIV Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 24, 2246717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.E.; Heitzeg, M.M. Heitzeg, Sex, age, race and intervention type in clinical studies of HIV cure: A systematic review. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2015, 31, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.A.; Turner, S.R.; Marsden, M.D. Contribution of Sex Differences to HIV Immunology, Pathogenesis, and Cure Approaches. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 905773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyein, P.P.; Aung, E.; Aung, N.M.; Kyi, M.M.; Boyd, M.; Lin, K.S.; Hanson, J. The impact of gender and the social determinants of health on the clinical course of people living with HIV in Myanmar: An observational study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G.; Archin, N.; Cannon, P.; Collins, S.; Jones, R.B.; de Jong, M.A.W.P.; Lambotte, O.; Lamplough, R.; Ndung’u, T.; Sugarman, J.; et al. Research priorities for an HIV cure: International AIDS Society Global Scientific Strategy 2021. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpani, A.; De Vito, A.; Zauli, B.; Menzaghi, B.; Calcagno, A.; Celesia, B.M.; Ceccarelli, M.; Nunnari, G.; De Socio, G.V.; Di Biagio, A.; et al. Knowledge of Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV among People Living with HIV: Should We Be Concerned? Healthcare 2024, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Paassen, P.; Dijkstra, M.; Peay, H.L.; Rokx, C.; Verbon, A.; Reiss, P.; Prins, J.M.; Henderson, G.E.; Rennie, S.; Nieuwkerk, P.T.; et al. Perceptions of HIV cure and willingness to participate in HIV cure-related trials among people enrolled in the Netherlands cohort study on acute HIV infection. J. Virus Erad. 2022, 8, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, R.; Kall, M.; Collins, S.; Cairns, G.; Taylor, S.; Nelson, M.; Fidler, S.; Porter, K.; Fox, J.; the Collaborative HIV Eradication of viral Reservoirs (CHERUB) Survey collaboration. A global survey of HIV-positive people’s attitudes towards cure research. HIV Med. 2017, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laher, F.; Mahlangu, N.; Sibiya, M. Beliefs about HIV cure: A qualitative study of people living with HIV in Soweto, South Africa. S. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Martin, K.; Corbett, A.; Napravnik, S.; Eron, J.; Zhu, Y.; Casciere, B.; Boulton, C.; Loy, B.; Smith, S.; et al. Total daily pill burden in HIV-infected patients in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014, 28, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Los Rios, P.; Okoli, C.; Castellanos, E.; Allan, B.; Young, B.; Brough, G.; Muchenje, M.; Eremin, A.; Corbelli, G.M.; McBritton, M.; et al. Physical, Emotional, and Psychosocial Challenges Associated with Daily Dosing of HIV Medications and Their Impact on Indicators of Quality of Life: Findings from the Positive Perspectives Study. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parienti, J.-J.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Verdon, R.; Gardner, E.M. Better adherence with once-daily antiretroviral regimens: A meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, C.; Milloy, M.-J.; Kerr, T.; Zhang, R.; Guillemi, S.; Hogg, R.S.; Montaner, J.; Wood, E. Female gender predicts lower access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a setting of free healthcare. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samnani, F.; Deering, K.; King, D.; Magagula, P.; Braschel, M.; Shannon, K.; Krüsi, A. Stigma trajectories, disclosure, access to care, and peer-based supports among African, Caribbean, and Black im/migrant women living with HIV in Canada: Findings from a cohort of women living with HIV in Metro Vancouver, Canada. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojikutu, B.O.; Amutah-Onukagha, N.; Mahoney, T.F.; Tibbitt, C.; Dale, S.D.; Mayer, K.H.; Bogart, L.M. HIV-Related Mistrust (or HIV Conspiracy Theories) and Willingness to Use PrEP Among Black Women in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2927–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, B.D.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. (Eds.) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.A.; Mager, N.A.D. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: Historical perspective and future implications. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 14, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepperrell, T.; Hill, A.; Moorhouse, M.; Clayden, P.; McCann, K.; Sokhela, S.; Serenata, C.; Venter, W.D.F. Phase 3 trials of new antiretrovirals are not representative of the global HIV epidemic. J. Virus Erad. 2020, 6, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Vulesevic, B.; Burchell, A.N.; Singer, J.; Needham, J.; Yang, Y.; Qian, H.; Chambers, C.; Samji, H.; Colmegna, I.; et al. Sex differences in COVID-19 vaccine confidence in people living with HIV in Canada. Vaccine X 2024, 21, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Westle, A.; Dowsett, G.W.; Lucke, J.; Tucker, J.D.; Sugarman, J.; Lewin, S.R.; Hill, S.; Brown, G.; Wallace, J.; et al. Perceptions of HIV cure research among people living with HIV in Australia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, D.; Dubé, K.; Bilodeau, M.; Keeler, P.; Margolese, S.; Rosenes, R.; Sinyavskaya, L.; Durand, M.; Benko, E.; Kovacs, C.; et al. Willingness of Older Canadians with HIV to Participate in HIV Cure Research Near and After the End of Life: A Mixed-Method Study. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2022, 38, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, K.; Dee, L.; Evans, D.; Sylla, L.; Taylor, J.; Brown, B.; Miller, V.; Corneli, A.; Skinner, A.; Greene, S.B.; et al. Perceptions of Equipoise, Risk-Benefit Ratios, and “Otherwise Healthy Volunteers” in the Context of Early-Phase HIV Cure Research in the United States: A Qualitative Inquiry. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2018, 13, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutterheim, S.E.; van Dijk, M.; Wang, H.; Jonas, K.J. The worldwide burden of HIV in transgender individuals: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Characteristics | Value | n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 53/109 (48.6%) |

| Woman | 51/109 (46.8%) | |

| Gender-diverse | 5/109 (4.6%) | |

| Assigned sex at birth | Male | 54/109 (49.5%) |

| Female | 54/109 (49.5%) | |

| Other | 1/109 (0.9%) | |

| Race | White | 56/109 (51.4%) |

| Black | 26/109 (23.9%) | |

| Latin American | 9/109 (8.3%) | |

| Caribbean | 6/109 (5.5%) | |

| South Asian | 5/109 (4.6%) | |

| Arab | 0/109 (0.0%) | |

| Filipino | 0/109 (0.0%) | |

| West Asian | 0/109 (0.0%) | |

| Self-descrribed | 11/109 (10.1%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 2/109 (1.8%) | |

| Indigenous | Yes | 11/109 (10.1%) |

| No | 98/109 (89.9%) | |

| Place of birth | Canada | 63/109 (57.8%) |

| Central Africa | 11/109 (10.1%) | |

| South Africa | 7/109 (6.4%) | |

| Europe | 6/109 (5.5%) | |

| North America (not Canada) | 6/109 (5.5%) | |

| Southeast Asia | 5/109 (4.6%) | |

| Caribbean and Bermuda | 4/109 (3.7%) | |

| Central America | 3/109 (2.8%) | |

| North Africa | 2/109 (1.8%) | |

| Eastern Asia | 1/109 (0.9%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1/109 (0.9%) | |

| Highest level of education | Less than high school graduation | 7/109 (6.4%) |

| High school graduation | 13/109 (11.9%) | |

| Non-university certificate or diploma from a community college, CEGEP | 35/109 (32.1%) | |

| Trade certificate, vocational school, or apprenticeship training | 12/109 (11.0%) | |

| University Bachelor’s degree | 29/109 (26.6%) | |

| University graduate degree (Master’s, Doctorate, etc.) | 12/109 (11.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1/109 (0.9%) | |

| Student | Yes | 9/109 (8.3%) |

| No | 99/109 (90.8%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1/109 (0.9%) | |

| Employment status | Employed | 50/109 (45.9%) |

| Unemployed | 48/109 (44.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 11/109 (10.1%) | |

| Work schedule | Full-time | 35/50 (70.0%) |

| Part-time | 15/50 (30.0%) | |

| Self-employed | Yes | 7/50 (14.0%) |

| No | 42/50 (84.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1/50 (2.0%) | |

| On disability leave | Yes | 5/50 (10.0%) |

| No | 45/50 (90.0%) | |

| Stay-at-home parent | Yes | 7/48 (14.6%) |

| No | 40/48 (83.3%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1/48 (2.1%) | |

| Retired | Yes | 28/109 (25.7%) |

| No | 78/109 (71.6%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3/109 (2.8%) | |

| Caregiver | Yes | 14/109 (12.8%) |

| No | 92/109 (84.4%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3/109 (2.8%) | |

| Length of HIV diagnosis | 4 years or less | 9/109 (8.3%) |

| 5–9 years | 14/109 (12.8%) | |

| 10–14 years | 12/109 (11.0%) | |

| 15–24 years | 35/109 (32.1%) | |

| 25 years or more | 39/109 (35.8%) | |

| HIV study participation | Yes | 78/109 (71.6%) |

| No | 19/109 (17.4%) | |

| Not sure | 10/109 (9.2%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 2/109 (1.8%) | |

| Interventional (not HIV) | Yes | 18/78 (23.1%) |

| No | 52/78 (66.7%) | |

| Not Sure | 8/78 (10.3%) | |

| Observational | Yes | 46/78 (59.0%) |

| No | 29/78 (37.2%) | |

| Not Sure | 3/78 (3.8%) | |

| Survey or interview | Yes | 70/78 (89.7%) |

| No | 7/78 (9.0%) | |

| Not Sure | 1/78 (1.3%) | |

| Knowledge score | 80% or higher | 109/109 (100.0%) |

| under 80% | 0/109 (0.0%) |

| White | Black | Latin American | Caribbean | South Asian | Southeast Asian | Self-Identified | Prefer Not to Answer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 35 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Woman | 18 | 19 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| Other | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, J.; Vulesevic, B.; Margolese, S.; Masching, R.; Tharao, W.; Cardinal, C.; Hedrich, T.; Mallais, C.; Dubé, K.; Cohen, E.; et al. The CanCURE Survey: Gender-Based Differences in HIV Cure Research Priorities. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120623

Lu J, Vulesevic B, Margolese S, Masching R, Tharao W, Cardinal C, Hedrich T, Mallais C, Dubé K, Cohen E, et al. The CanCURE Survey: Gender-Based Differences in HIV Cure Research Priorities. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120623

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Jessica, Branka Vulesevic, Shari Margolese, Renee Masching, Wangari Tharao, Claudette Cardinal, Tanguy Hedrich, Chris Mallais, Karine Dubé, Eric Cohen, and et al. 2025. "The CanCURE Survey: Gender-Based Differences in HIV Cure Research Priorities" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120623

APA StyleLu, J., Vulesevic, B., Margolese, S., Masching, R., Tharao, W., Cardinal, C., Hedrich, T., Mallais, C., Dubé, K., Cohen, E., Chomont, N., & Costiniuk, C. T. (2025). The CanCURE Survey: Gender-Based Differences in HIV Cure Research Priorities. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120623