The Heterogeneous Interplay Between Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity in Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition from Public Datasets

2.1.1. Bulk Transcriptome Data on Lovo Cells Stimulated by Metformin (GSE67342)

2.1.2. Single Cell RNA-Sequencing Performed on Colorectal Tumors (GSE222300)

2.1.3. Bulk Transcriptome of Primary Colorectal Tumors from Stage II (GSE44076)

2.1.4. Multi-Center Bulk Transcriptome of Primary Colorectal Tumors with Prognosis Meta-Data (GSE103479)

2.2. Software Development

2.2.1. Development of the “Keggmetascore” R-Package

2.2.2. Development of the “Mitoscore” R-Package

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Single Cell RNA-Sequencing Analyses

2.3.2. Colorectal Cancer Consensus via Molecular Subtype Classification

2.3.3. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

2.3.4. Machine Learning by Elastic-Net to Predict BRAF-V600E Mutation Status with Metabolism/Mitochondria Activities

2.3.5. Mixed Metabolism/Mitochondria Activity Scores

2.3.6. Survival Analyses

2.3.7. Multivariable Logistic Analysis

2.4. Process of Metabolism and Mitochondria Multi-Modal Integration in Transcriptome Data of Colorectal Tumor Cells

3. Results

3.1. Metformin Conjointly Regulated Metabolism and Mitochondria After 24 h in LOVO Cells

3.2. Metabolic and Mitochondrial Heterogeneity at Single-Cell Level in Colorectal Tumor Cells

3.3. Colorectal Tumors Harbored Major Repression of Their Metabolism/Mitochondria Activity as Compared to Normal Tissues

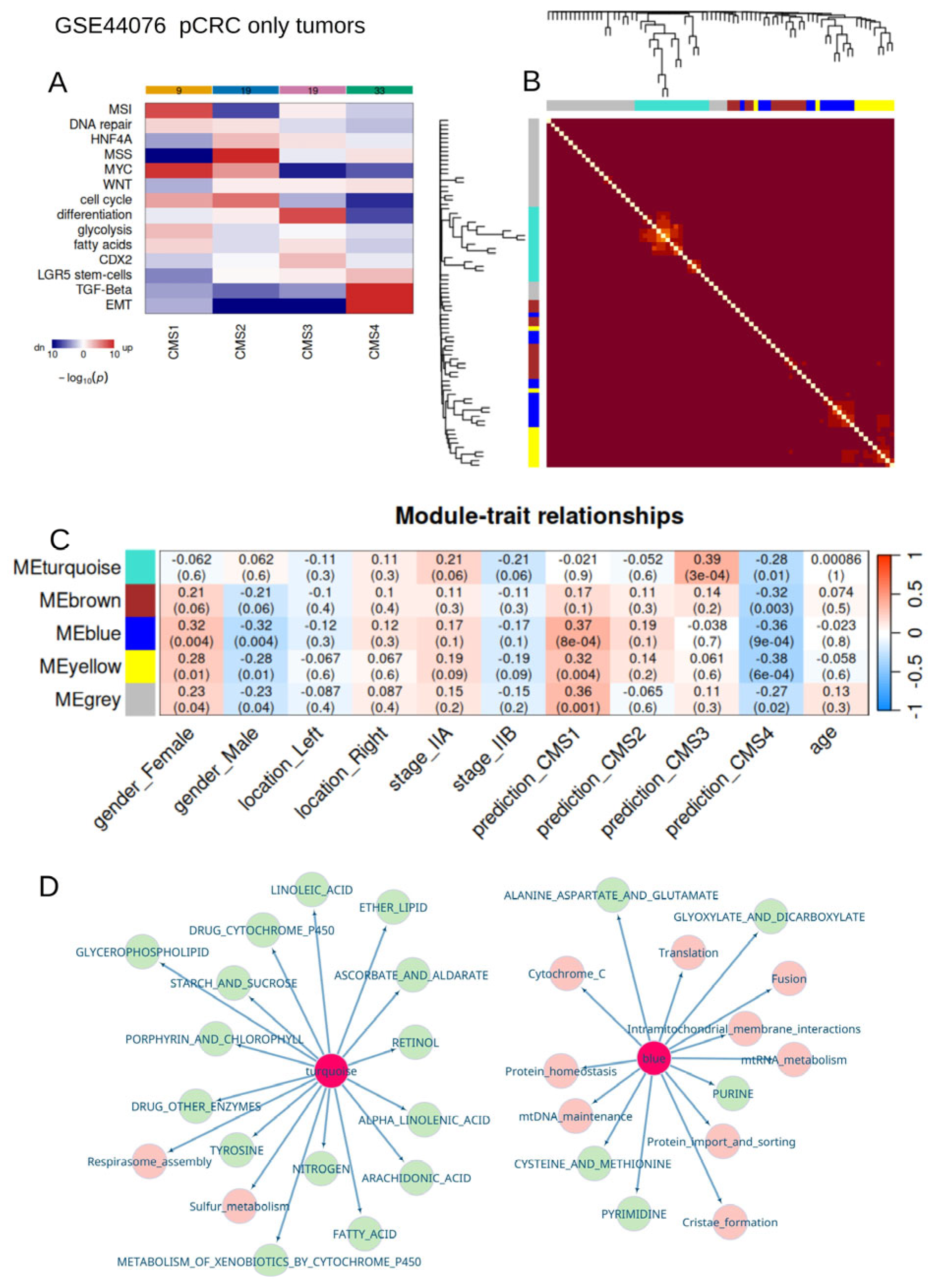

3.4. Metabolism/Mitochondria Activities Are Associated with Consensus Molecular Classification During Colorectal Cancer

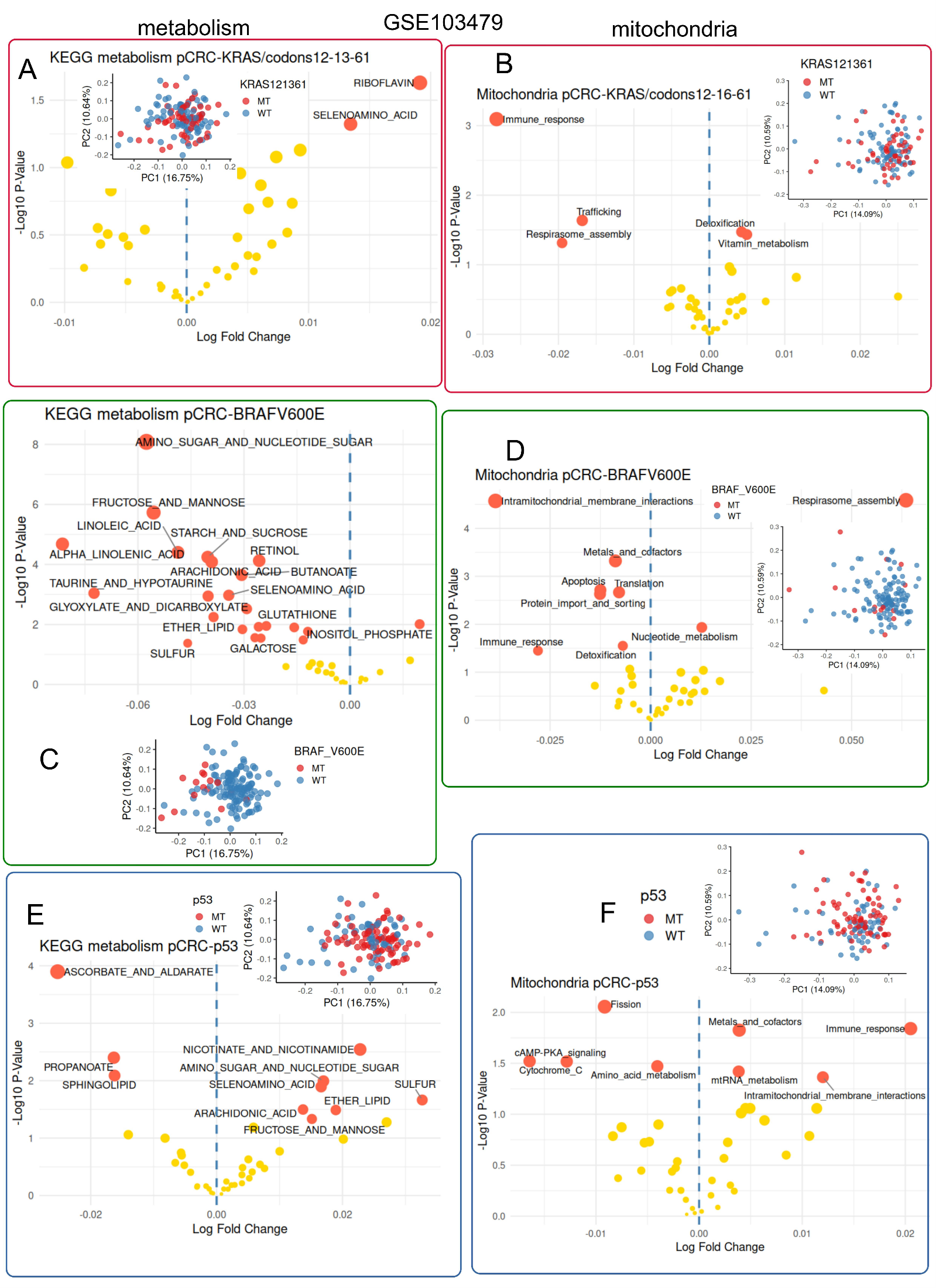

3.5. Colorectal Tumors Mutated for BRAFV600E Harbored Strong Metabolism Repression Associated with Fewer Intramitochondrial Membrane Interactions

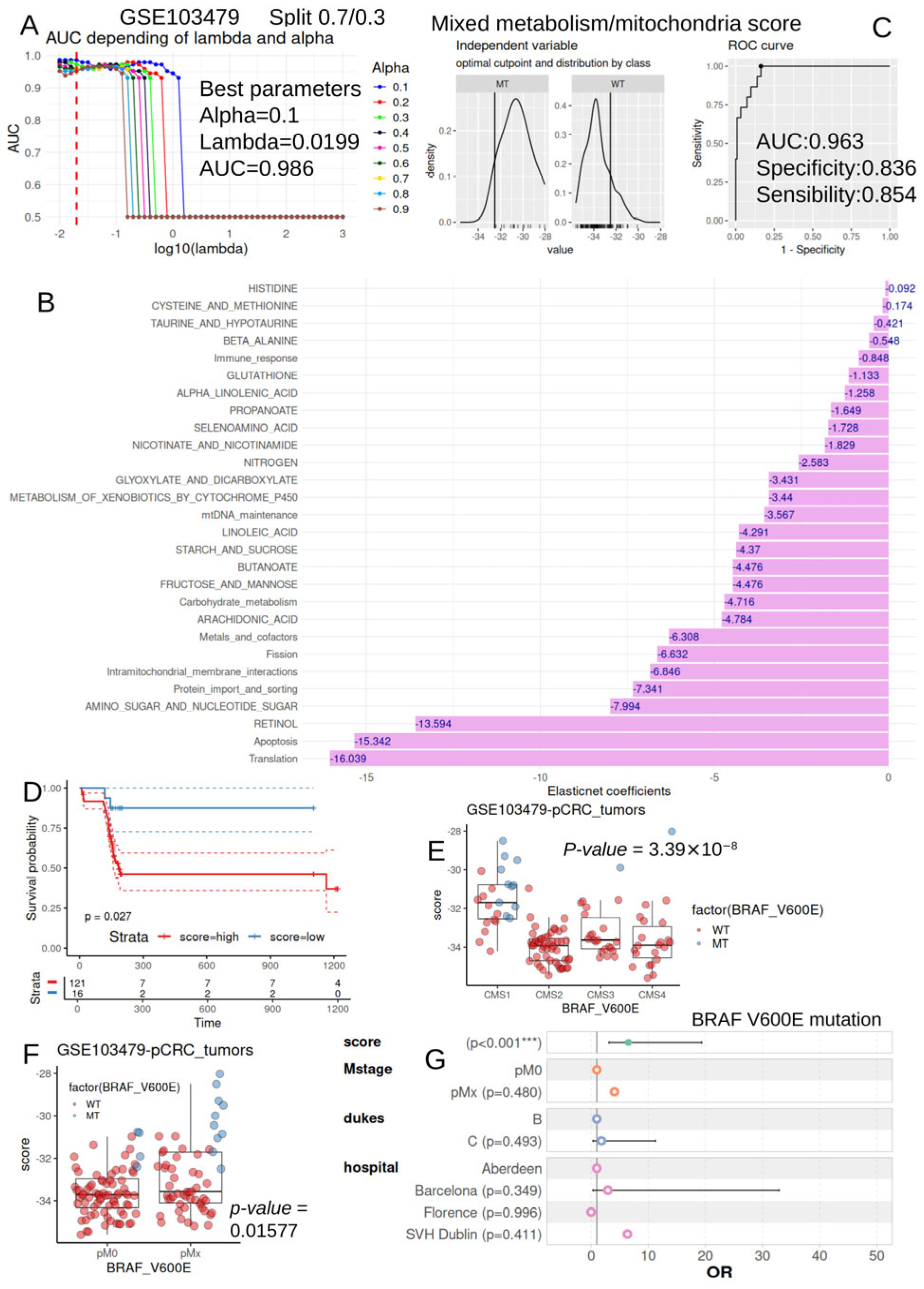

3.6. Metabolism/Mitochondria Activity Score Is an Independent Parameter to Predict BRAF-V600E Mutation Status During Colorectal Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CMS | Consensus molecular subtypes |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araghi, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jenkins, M.; Brierley, J.; Morris, E.; Bray, F.; Arnold, M. Global Trends in Colorectal Cancer Mortality: Projections to the Year 2035. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2992–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porporato, P.E.; Payen, V.L.; Baselet, B.; Sonveaux, P. Metabolic Changes Associated with Tumor Metastasis, Part 2: Mitochondria, Lipid and Amino Acid Metabolism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 1349–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, S. Editorial: Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Metabolism: Implication for Human Health and Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1468758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E. THE METABOLISM OF TUMORS IN THE BODY. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaneophytou, C. The Warburg Effect: Is it Always an Enemy? Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.E.; Short, S.P.; Williams, C.S. Colorectal Cancer and Metabolism. Curr. Color. Cancer Rep. 2018, 14, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, Y.; Taniguchi, K. Intratumoral Metabolic Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 325, C1073–C1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, D.; Casey, R.; Gottlieb, E. Knowledge-Based Therapeutics for Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle-Deficient Cancers. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; White, D.W.; Gross, S.; Bennett, B.D.; Bittinger, M.A.; Driggers, E.M.; Fantin, V.R.; Jang, H.G.; Jin, S.; Keenan, M.C.; et al. Cancer-Associated IDH1 Mutations Produce 2-Hydroxyglutarate. Nature 2009, 462, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.E.; Bittinger, M.A.; Su, S.M.; Fantin, V.R. Cancer-Associated IDH Mutations: Biomarker and Therapeutic Opportunities. Oncogene 2010, 29, 6409–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.A.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.-W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for Microsatellite Instability-High or Mismatch Repair-Deficient Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (KEYNOTE-177): Final Analysis of a Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Guo, T.; Yang, J.; Shao, Z.; Cai, G.; Cai, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Molecular Profiling Provides Clinical Insights Into Targeted and Immunotherapies as Well as Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 414–428.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, H.; Goto, S.; Sato, K.; Fujibuchi, W.; Bono, H.; Kanehisa, M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, S.; Sharma, R.; Gupta, R.; Ast, T.; Chan, C.; Durham, T.J.; Goodman, R.P.; Grabarek, Z.; Haas, M.E.; Hung, W.H.W.; et al. MitoCarta3.0: An Updated Mitochondrial Proteome Now with Sub-Organelle Localization and Pathway Annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1541–D1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, K.; Zheng, N.; Qiu, Y.; Xie, G.; Su, M.; Jia, W.; Li, H. Metformin Suppressed the Proliferation of LoVo Cells and Induced a Time-Dependent Metabolic and Transcriptional Alteration. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, X.; Crous-Bou, M.; Cordero, D.; Olivares, D.; Guinó, E.; Sanz-Pamplona, R.; Rodriguez-Moranta, F.; Sanjuan, X.; de Oca, J.; Salazar, R.; et al. Discovery and Validation of New Potential Biomarkers for Early Detection of Colon Cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, W.L.; Dunne, P.D.; McDade, S.; Scanlon, E.; Loughrey, M.; Coleman, H.; McCann, C.; McLaughlin, K.; Nemeth, Z.; Syed, N.; et al. Transcriptional Subtyping and CD8 Immunohistochemistry Identifies Poor Prognosis Stage II/III Colorectal Cancer Patients Who Benefit from Adjuvant Chemotherapy. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Johnson, W.E.; Parker, H.S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Storey, J.D. The Sva Package for Removing Batch Effects and Other Unwanted Variation in High-Throughput Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 882–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological Systems Database as A Model of the Real World. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene Set Variation Analysis for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Hoffman, P.; Smibert, P.; Papalexi, E.; Satija, R. Integrating Single-Cell Transcriptomic Data across Different Conditions, Technologies, and Species. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Stuart, T.; Kowalski, M.H.; Choudhary, S.; Hoffman, P.; Hartman, A.; Srivastava, A.; Molla, G.; Madad, S.; Fernandez-Granda, C.; et al. Dictionary Learning for Integrative, Multimodal and Scalable Single-cell Analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 42, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElKarami, B.; Alkhateeb, A.; Qattous, H.; Alshomali, L.; Shahrrava, B. Multi-omics Data Integration Model Based on UMAP Embedding and Convolutional Neural Network. Cancer Informatics. 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.L.; Zanella, L.; Ochiai, Y.; Golinelli, L.; Califano, A.; Malagola, E.; Vasciaveo, A. Protocol for Automated Graph-based Clustering of Single-cell RNA-seq Data with Application in Mouse Intestinal Stem Cells. STAR Protoc. 2025, 6, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, P.W.; Bruun, J.; Lothe, R.A.; Sveen, A. CMScaller: An R Package for Consensus Molecular Subtyping of Colorectal Cancer Pre-Clinical Models. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S. Weighted Network Analysis; Applications in Genomics and Systems Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-8819-5. [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Mukhtar, S. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Exploration Using Cytoscape. In: Mukhtar, S. (eds) Protein-Protein Interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2023, 2690, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R. Using the Caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic Net Regularization Paths for All Generalized Linear Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 106, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.; Hirschfeld, G. Cutpointr: Improved Estimation and Validation of Optimal Cutpoints in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2021, 98, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therneau, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, M.; Diprose, W.; Brown, S.B.; Ospel, J.M.; Holodinsky, J.K. Statistical Principles in Neurointervention Part 2. Multivariable Analysis: Generalized Linear Models, Modification, Confounding, and Mediation. J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2025, 17, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-J.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Kan, H.; Song, Y.; Cui, W.; Zhao, G.; Kip, K.E. Reduced Risk of Colorectal Cancer with Metformin Therapy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridges, H.R.; Jones, A.J.Y.; Pollak, M.N.; Hirst, J. Effects of Metformin and Other Biguanides on Oxidative Phosphorylation in Mitochondria. Biochem. J. 2014, 462, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosono, K.; Endo, H.; Takahashi, H.; Sugiyama, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Suzuki, K.; Nozaki, Y.; Yoneda, K.; Fujita, K.; Yoneda, M.; et al. Metformin Suppresses Azoxymethane-Induced Colorectal Aberrant Crypt Foci by Activating AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Mol. Carcinog. 2010, 49, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.R.; Wang, T.; Chan, K.Y.; Trotter, E.W.; Gillespie, A.; Michael, M.Z.; Oakhill, J.S.; Hagan, I.M.; Petersen, J. Elevated Basal AMP-activated Protein Kinase Activity Sensitizes Colorectal Cancer Cells to Growth Inhibition by Metformin. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 230021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Okabayashi, K.; Seishima, R.; Ishida, T.; Shigeta, K.; Tsuruta, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Kitagawa, Y. Metformin Inhibits the Development and Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Med Oncol. 2022, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, W.W.; Weinberg, S.E.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Soberanes, S.; Sullivan, L.B.; Anso, E.; Glasauer, A.; Dufour, E.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budigner, G.S.; et al. Metformin Inhibits Mitochondrial Complex I of Cancer Cells to Reduce Tumorigenesis. eLife 2014, 3, e02242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chakrabarty, R.P.; D’aLessandro, K.B.; Sebo, Z.L.; Grant, R.A.; Gao, P.; Budinger, G.R.; Chandel, N.S. Metformin Targets Mitochondrial Complex I to Lower Blood Glucose Levels. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eads5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, H.A.; Iliopoulos, D.; Tsichlis, P.N.; Struhl, K. Metformin Selectively Targets Cancer Stem Cells, and Acts Together with Chemotherapy to Block Tumor Growth and Prolong Remission. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 7507–7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, E.; Montazeri, V.; Aliebrahimi, S.; Sezavar, A.H.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Ostad, S.N. Targeting Cancer Stem Cells and Hedgehog Pathway: Enhancing Cisplatin Efficacy in Ovarian Cancer With Metformin. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabkhizan, R.; Avci, Ç.B.; Haiaty, S.; Moslehian, M.S.; Sadeghsoltani, F.; Bazmani, A.; Mahdipour, M.; Takanlou, L.S.; Takanlou, M.S.; Zamani, A.R.N.; et al. Metformin Exerted Tumoricidal Effects on Colon Cancer Tumoroids via the Regulation of Autophagy Pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribbs, J.T.; Strack, S. Reversible Phosphorylation of Drp1 by Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase and Calcineurin Regulates Mitochondrial Fission and Cell Death. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Peng, W.; Ji, J.; Peng, C.; Wang, T.; Yang, P.; Gu, J.; Feng, Y.; Jin, K.; Wang, X.; et al. GPR176 Promotes Cancer Progression by Interacting with G Protein GNAS to Restrain Cell Mitophagy in Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-García, J.L.; Martínez-Torrecuadrada, J.L.; Epifano, C.; Cañamero, M.; Babel, I.; Casal, J.I. Differential Protein Expression on the Cell Surface of Colorectal Cancer Cells Associated to Tumor Metastasis. Proteomics 2010, 10, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Ni, X.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, G.; Shi, T.; Chen, W. FASN Promotes Lipid Metabolism and Progression in Colorectal Cancer via the SP1/PLA2G4B Axis. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytseva, Y.Y.; Rychahou, P.G.; Gulhati, P.; Elliott, V.A.; Mustain, W.C.; O’Connor, K.; Morris, A.J.; Sunkara, M.; Weiss, H.L.; Lee, E.Y.; et al. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Synthase Attenuates CD44-Associated Signaling and Reduces Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1504–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Gong, Z.-C.; Li, C.-Q.; Teng, P.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Huang, Z.-H. Global Research Trends and Prospects of Cellular Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergers, G.; Fendt, S.-M. The Metabolism of Cancer Cells during Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021, 21, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, M.J.; Lonardi, S.; Wong, K.Y.M.; Lenz, H.-J.; Gelsomino, F.; Aglietta, M.; Morse, M.A.; Van Cutsem, E.; McDermott, R.; Hill, A.; et al. Durable Clinical Benefit With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in DNA Mismatch Repair-Deficient/Microsatellite Instability-High Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Wu, H. Metabolic Reprogramming in Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Aerobic Glycolysis and Its Therapeutic Implications for Targeted Treatment Strategies. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-García, L.C.; García-Castillo, V.; Pérez-Toledo, E.; Trujano-Camacho, S.; Millán-Catalán, O.; Pérez-Yepez, E.A.; Coronel-Hernández, J.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, M.; Jacobo-Herrera, N.; Pérez-Plasencia, C. HOTAIR Participation in Glycolysis and Glutaminolysis Through Lactate and Glutamate Production in Colorectal Cancer. Cells. 2025, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Su, F.; Li, Q.; Wen, Y.; Wei, F.; He, Z.; Chen, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; et al. Phytochemicals Targeting Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer Therapy: Effects and Mechanisms of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1257450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.G.; Rao, S.; Weir, T.L.; O’Malia, J.; Bazan, M.; Brown, R.J.; Ryan, E.P. Metabolomics and Metabolic Pathway Networks from Human Colorectal Cancers, Adjacent Mucosa, and Stool. Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; De Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The Consensus Molecular Subtypes of Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaprio, T.; Hagström, J.; Kasurinen, J.; Gkekas, I.; Edin, S.; Beilmann-Lehtonen, I.; Strigård, K.; Palmqvist, R.; Gunnarson, U.; Böckelman, C.; et al. An Immunohistochemistry-based Classification of Colorectal Cancer Resembling the Consensus Molecular Subtypes Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Health and Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Vizarra, E.; Callegari, S.; Garrabou, G.; Pacheu-Grau, D. Editorial: Mitochondrial OXPHOS System: Emerging Concepts and Technologies and Role in Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 924272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, F.; Hamanaka, R.; Wheaton, W.W.; Weinberg, S.; Joseph, J.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial Metabolism and ROS Generation Are Essential for Kras-Mediated Tumorigenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8788–8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Hoyo, A.; Monzonís, X.; Vidal, J.; Linares, J.; Montagut, C. Unveiling Acquired Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapies in Colorectal Cancer: A Long and Winding Road. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1398419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torounidou, N.; Yerolatsite, M.; Zarkavelis, G.; Amylidi, A.-L.; Karafousia, V.; Kampletsas, E.; Mauri, D. Treatment Sequencing in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Wspolczesna Onkol. Oncol. 2024, 28, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallbone, K.; Gatenby, R.A.; Gillies, R.J.; Maini, P.K.; Gavaghan, D.J. Metabolic Changes during Carcinogenesis: Potential Impact on Invasiveness. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 244, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Fang, H.; Wang, R.; Dai, W.; Cai, G. A Comprehensive Overview of the Molecular Features and Therapeutic Targets in BRAFV600E-mutant Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yang, B. The Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Regulating Cancer Metastasis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Pervaiz, S. Bcl-2 Induces pro-Oxidant State by Engaging Mitochondrial Respiration in Tumor Cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, B.; Shu, H.; Lyu, J.; Cui, W.; Fang, H. Oxidative Phosphorylation at the Crossroads of Cancer: Metabolic orchestration, Stromal Collusion, and Emerging Therapeutic Horizons. Interdiscip. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş, E.; Lyakhovich, A. Targeting the Bioenergetics of A Resistant Tumor: Clinical Insights into OXPHOS Inhibition for Cancer Therapy. Redox Exp. Med. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caino, M.C.; Chae, Y.C.; Vaira, V.; Ferrero, S.; Nosotti, M.; Martin, N.M.; Weeraratna, A.; O’Connell, M.; Jernigan, D.; Fatatis, A.; et al. Metabolic Stress Regulates Cytoskeletal Dynamics and Metastasis of Cancer Cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2907–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Gibbs, P.; Lipton, L.; Christie, M.; Jorissen, R.N.; Burgess, A.W.; Croxford, M.; Jones, I.; Langland, R.; Kosmider, S.; et al. Optimizing Targeted Therapeutic Development: Analysis of a Colorectal Cancer Patient Population with the BRAFV600EMutation. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 2075–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, I.; Hirota, T.; Shinozaki, E. BRAF Mutation in Colorectal Cancers: From Prognostic Marker to Targetable Mutation. Cancers 2020, 12, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, G.N.; Dal Pozzo, C.A.; Depetris, I.; Schirripa, M.; Brignola, S.; Biason, P.; Balistreri, M.; Dal Santo, L.; Lonardi, S.; Munari, G.; et al. The Heterogeneous Clinical and Pathological Landscapes of Metastatic Braf-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Level | Mucosa (n = 50) | Normal (n = 98) | Tumor (n = 98) | Total (n = 246) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | Mean (sd) | 62.5 (14.2) | 70.5 (9) | 70.5 (9) | 68.9 (10.7) | <1 × 10−4 |

| Gender | Male | 27 (54.0) | 71 (72.4) | 71 (72.4) | 169 (68.7) | |

| Female | 23 (46.0) | 27 (27.6) | 27 (27.6) | 77 (31.3) | 0.04273 | |

| Tumor location | Left | 23 (46.0) | 60 (61.2) | 60 (61.2) | 143 (58.1) | |

| Right | 27 (54.0) | 38 (38.8) | 38 (38.8) | 103 (41.9) | 0.15003 | |

| Tumor stage | IIA | not available | not available | 90 (91.8) | 90 (91.8) | |

| IIB | not available | not available | 8 (8.2) | 8 (8.2) | not available |

| Variable | Level | Low (n = 102) | High (n = 35) | Total (n = 137) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Aberdeen | 10 (9.8) | 14 (40.0) | 24 (17.5) | |

| Barcelona | 41 (40.2) | 11 (31.4) | 52 (38.0) | ||

| Florence | 17 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (12.4) | ||

| SVH Dublin | 34 (33.3) | 10 (28.6) | 44 (32.1) | 0.0001612 | |

| tumor_size | mean (sd) | 4.9 (1.8) | 5.6 (2.6) | 5.1 (2.1) | 0.1030527 |

| Tumor stage | pT4 | 3 (2.9) | 6 (17.1) | 9 (6.6) | |

| pT3 | 77 (75.5) | 22 (62.9) | 99 (72.3) | ||

| pT2 | 5 (4.9) | 1 (2.9) | 6 (4.4) | ||

| pT4a | 8 (7.8) | 2 (5.7) | 10 (7.3) | ||

| pT4b | 8 (7.8) | 4 (11.4) | 12 (8.8) | ||

| pT1 | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.0838208 | |

| Nodule stage | pN0 | 57 (55.9) | 17 (48.6) | 74 (54.0) | |

| pN1 | 20 (19.6) | 5 (14.3) | 25 (18.2) | ||

| pN2 | 5 (4.9) | 3 (8.6) | 8 (5.8) | ||

| pN2a | 3 (2.9) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (3.6) | ||

| pN1a | 8 (7.8) | 4 (11.4) | 12 (8.8) | ||

| pN1b | 6 (5.9) | 2 (5.7) | 8 (5.8) | ||

| pN2b | 3 (2.9) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (3.6) | 0.8400949 | |

| Metastasis stage | pMx | 35 (34.3) | 22 (62.9) | 57 (41.6) | |

| pM0 | 67 (65.7) | 13 (37.1) | 80 (58.4) | 0.0058267 | |

| lymph_nodes_excised | mean (sd) | 21.8 (16) | 18.8 (8.7) | 21 (14.5) | 0.2857346 |

| age_diagnosis | mean (sd) | 69.9 (11.3) | 70.4 (12.3) | 70 (11.5) | 0.8049928 |

| CMS | CMS1 | 6 (6.7) | 17 (58.6) | 23 (19.3) | |

| CMS2 | 50 (55.6) | 2 (6.9) | 52 (43.7) | ||

| CMS4 | 18 (20.0) | 4 (13.8) | 22 (18.5) | ||

| CMS3 | 16 (17.8) | 6 (20.7) | 22 (18.5) | < 1 × 10−4 | |

| BRAF_V600E mutation | WT | 102 (100.0) | 20 (57.1) | 122 (89.1) | |

| MT | 0 (0.0) | 15 (42.9) | 15 (10.9) | < 1 × 10−4 | |

| TP53 mutation | WT | 40 (39.2) | 19 (54.3) | 59 (43.1) | |

| MT | 62 (60.8) | 16 (45.7) | 78 (56.9) | 0.1751699 | |

| KRAS (12-13-61) position mutations | MT | 42 (41.2) | 12 (34.3) | 54 (39.4) | |

| WT | 60 (58.8) | 23 (65.7) | 83 (60.6) | 0.603493 | |

| Overall Survival (months) | mean (sd) | 233.2 (292.9) | 146.2 (47.4) | 211 (256.4) | 0.0810742 |

| Overall survival status | alive | 60 (58.8) | 22 (62.9) | 82 (59.9) | |

| dead | 42 (41.2) | 13 (37.1) | 55 (40.1) | 0.8256887 | |

| Progression free survival (months) | mean (sd) | 55.5 (41.2) | 44.1 (32.4) | 52.6 (39.4) | 0.138873 |

| Recurrence status | no | 73 (73.0) | 24 (68.6) | 97 (71.9) | |

| yes | 27 (27.0) | 11 (31.4) | 38 (28.1) | 0.7771385 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | yes | 42 (42.4) | 13 (37.1) | 55 (41.0) | |

| no | 57 (57.6) | 22 (62.9) | 79 (59.0) | 0.7292902 |

| Term | Odds Ratios | CI95-Low | CI95-High | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism/mitochondria score | 6.53 × 100 | 3.13 × 100 | 1.94 × 101 | 3.32 × 10−5 * |

| Mstage (pMx) | 4.09 × 100 | 1.51 × 10−1 | 3.17 × 102 | 4.80 × 10−1 |

| Dukes (Stage C) | 1.82 × 100 | 3.33 × 10−1 | 1.13 × 101 | 4.93 × 10−1 |

| Hospital (Barcelona) | 2.93 × 100 | 3.24 × 10−1 | 3.29 × 101 | 3.49 × 10−1 |

| hospital (Florence) | 3.27 × 10−6 | non available | 3.44 × 1077 | 9.96 × 10−1 |

| Hospital (SVH-Dublin) | 6.36 × 100 | 1.43 × 10−1 | 9.00 × 102 | 4.11 × 10−1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Desterke, C.; Fu, Y.; Mata-Garrido, J.; Hamaï, A.; Chang, Y. The Heterogeneous Interplay Between Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity in Colorectal Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120571

Desterke C, Fu Y, Mata-Garrido J, Hamaï A, Chang Y. The Heterogeneous Interplay Between Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120571

Chicago/Turabian StyleDesterke, Christophe, Yuanji Fu, Jorge Mata-Garrido, Ahmed Hamaï, and Yunhua Chang. 2025. "The Heterogeneous Interplay Between Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity in Colorectal Cancer" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120571

APA StyleDesterke, C., Fu, Y., Mata-Garrido, J., Hamaï, A., & Chang, Y. (2025). The Heterogeneous Interplay Between Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120571