Abstract

In recent years, recognizing patients’ experiential knowledge to improve the quality of care has resulted in the participation of patient advisors at various levels of healthcare systems. Some who are working at the clinical level are called accompanying patients (AP). A PRISMA-ScR exploratory scoping review of the literature was conducted on articles published from 2005 to 2021. Articles not in English or French and grey literature were excluded. The databases searched included Medline, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The data were organized according to the similarities in the ethical foundations of the included papers. Out of 2095 identified papers, 8 met inclusion criteria. Terms used to describe APs included peer support, resource parent, and peer health mediator. The clinical settings included psychiatry/mental health and neonatology. APs, patients, healthcare professionals, managers and policy makers were included in the studies. Three personal ethical foundations describing the foundations of the AP role were found: resilience, listening skills and altruism. The ethical foundations of this role also addressed interpersonal and interprofessional relationships with other actors in the healthcare system. The literature on the ethical foundations of APs is sparse, with heterogeneous methodologies. Further studies mobilizing well-defined methodologies would further validate the current results and deepen our understanding of the ethical foundations of the AP role.

1. Introduction

In recent years, recognizing patients’ experiential knowledge to enhance quality of care has resulted in the creation of the role of patient advisors (PAs). PAs are patients, currently or previously receiving care, participating in various levels of the healthcare system. They are involved in clinical care, research, policy making, and the training of health professionals [1]. At the clinical level, PAs are known as accompanying patient (AP) and they develop experiential knowledge through living with a health condition and receiving healthcare services. They complement the scientific and professional knowledge of caregivers, researchers, and trainers. Inscribed in the Montreal model [2], the care partnerships between an AP, a healthcare team and patients allow patients to invest in their care, make informed decisions based on their life plans and become their own caregivers. At the clinical level, the AP role is rooted in a desire to mobilize APs’ expertise as patients beyond their own care, to provide emotional, informational, and educational support to other patients who are experiencing situations that they may have experienced themselves. APs complement the services offered by healthcare professionals by providing additional and unique expertise stemming from their personal experiences in the healthcare system. The particularity of the AP role is that an AP becomes a full member of the team, developing interpersonal and interprofessional relationships with all parties in the healthcare network. However, the arrival of this new actor in clinical teams raises certain ethical questions, particularly regarding integration, contribution and recognition, in addition to issues of confidentiality and the loyalty conflicts that arise when exercising this role [3,4]. Researchers have addressed some of the ethical issues underlying the introduction of APs at different levels of the healthcare system, including highlighting emerging ethical issues [1,4,5,6] such as remuneration, tokenism, and the professionalization of this role [4]. These issues call for work to clarify and define the ethical foundations of the emerging AP role and of its position within the clinical team. In order to bring forth the ethical foundations of the role of AP, we intend to describe the principles, values, and motivations that guided APs toward the healthcare system and encouraged them to become involved and help other patients living with a similar health condition [7]. This is a skill set of intrinsic know-how competencies based on who APs are and what they needed to mobilize to be part of a clinical team, including the organizational imperative of healthcare systems. APs’ ethical foundation may be compared to the professional conduct expected by employees/staff members in healthcare systems.

We conducted an exploratory scoping review of the ethical foundations underlying the AP role. This review is part of an overarching project, PAROLE-Onco (Le Patient Accompagnateur, une Ressource Organisationnelle comme Levier pour une Expérience patient améliorée en oncologie/[The Accompanying Patient, an Organizational Resource as a Lever for an Enhanced Oncology Patient Experience]), which seeks to better understand the concept of patient advocates as integral members of clinical teams and their impact on the quality and safety of care. These caregivers are patients who have experienced a health condition and are sharing their experience and experiential knowledge to the benefit of other patients with the same health problem.

2. Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used as a guideline to ensure the methodological transparency of this review [8]. This scoping review was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley framework [9]. The framework consists of the following six stages: (1) identifying the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting the studies, (4) charting the data, (5) collating and summarizing, and (6) reporting the results.

2.1. Research Questions

This scoping review was based on the following research questions:

- What are the motivations and the reasons for which accompanying patients become involved with other patients with a similar health problem?

- What is the nature of the relationship between accompanying patients and various other actors in the healthcare system (i.e., the patients advised, the health professionals and the health organizations)?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

The following eligibility criteria were established to guide the literature review. We included articles published from 2005 to 2021 to reflect the recent nature of patient partnership. This time period was selected because partnership models with patient-centered approaches to care emerged in the early 2010s [2].

We included publications in English and French whose designs produced primary empirical and theoretical studies (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) that were published in the peer-reviewed literature. Publications were excluded if they were considered grey literature (e.g., reports, theses, newsletters). The target population was accompanying patients.

The studies eligible for inclusion were those in which the AP was involved with both patients and healthcare personnel at the same time and for the same purpose. Articles on patient engagement in their own care, decision-making, research, and training were excluded.

Medline, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases were used to capture the literature published in the medical and social science domains. These databases were selected to effectively capture an extended range of literature and to avoid literature in disciplines irrelevant to the topic. The search strategy was developed in Ovid Medline (Box 1). It consisted of keywords and subject headings. It was then adapted for use with other databases. The electronic databases were searched in April 2021.

Box 1. Search Strategy in Ovid Medline

Ethics, Medical/ OR Ethics, Clinical/ OR Ethics/ OR Ethics, Nursing/ OR Ethics, Pro-fessional/ OR Ethics, Institutional/ OR “Attitude of Health Personnel”/

AND

Patient participation/ OR patient engagement OR patient partner OR patient re-source OR patient expert OR patient advisor

2.3. Study Selection

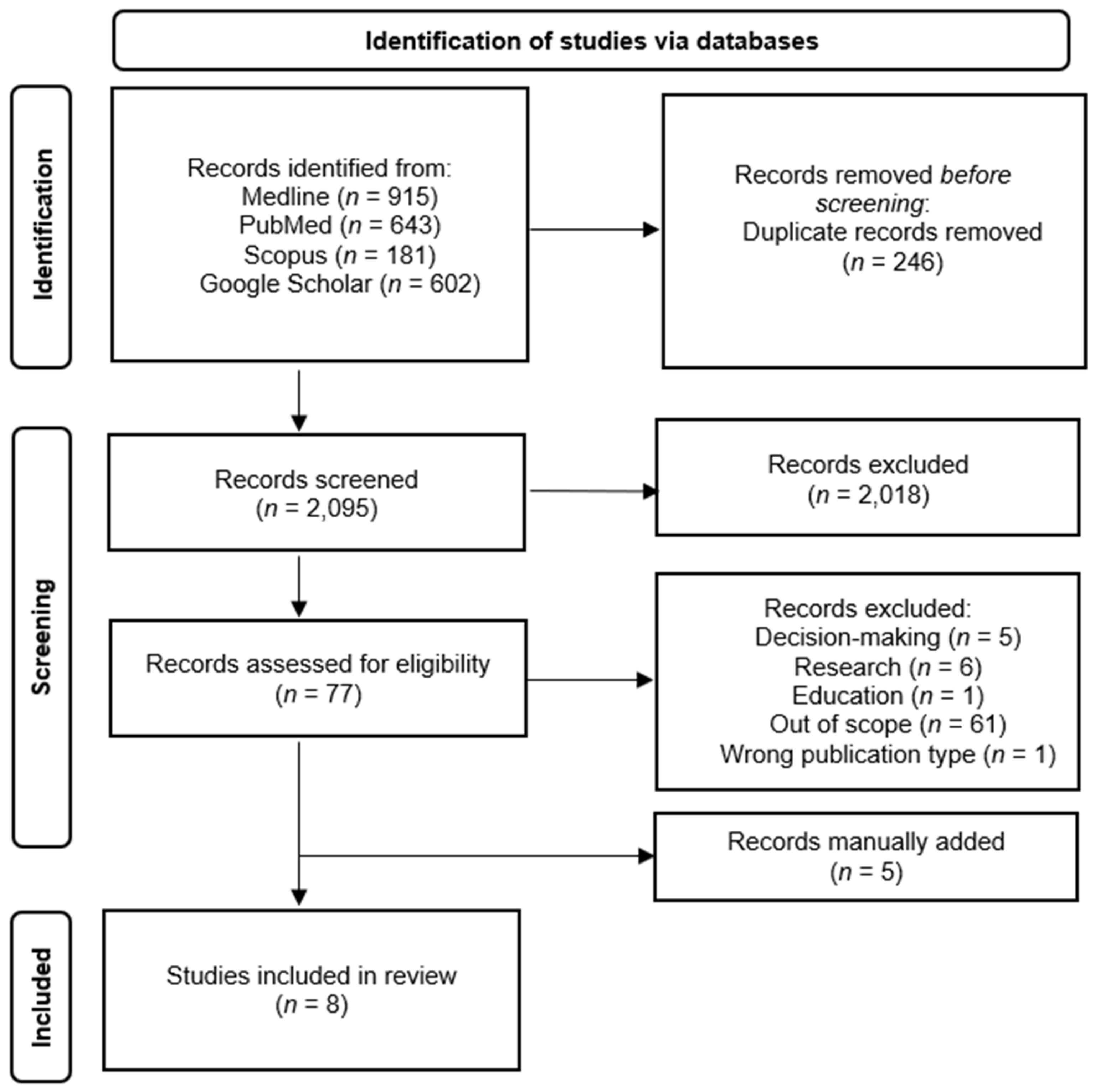

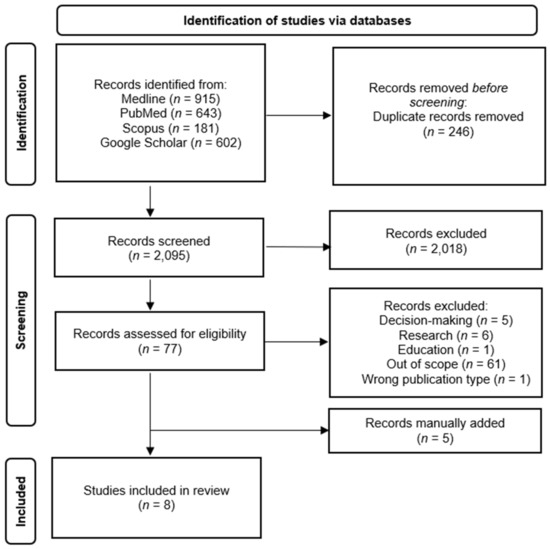

After duplicates were removed, a total of 2095 articles titles and abstracts were assessed for eligibility by the first author (MS) and 20% of them were reviewed by the second author (AF). The screening process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n [10].

2.4. Charting the Data

An inductive data extraction chart was developed based on an initial analysis of 25% of the data. The chart was further refined and validated with a multidisciplinary team of researchers in public health, medicine, ethics, and sociology. One reviewer collected the data (MS) and another reviewer (AF) double-checked 20% of the data collected. A third senior reviewer (IG) was consulted as needed to confirm the charting process. The following data were extracted from the selected articles:

- Descriptive characteristics (e.g., author, year, country, publication date, setting, study aim, study design, participants’ characteristics, and the term used to describe accompanying patients) were collected;

- Relevant results were organized on AP involvement at various levels (e.g., the personal, clinical and systemic levels);

- The data were organized according to similarities in the ethical foundations discussed in the articles.

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the 2018 version of the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [11].

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

This scoping review mobilized a narrative sociological approach that provides a comprehensive view of the value added by accompanying patients in the ecosystem of a healthcare system. This approach is supported by the link between patients and APs, based on connections with respect to the series of events that constitute their lived experience in various structures [12]. Consequently, we focus our reading on the narrative role of APs in the relational and social domains, taking into consideration the dynamic between professional and personal perspectives [12]. We chose this approach because the role of AP is halfway between a helping and a caring relationship [13]. Acting on several levels within institutions [12], we noted, based on the literature, the AP’s interventions in the relational chain of the hospital environment [14]. The nature of the links with healthcare personnel and the environment is a determining factor in the perceived quality of the services obtained [14,15]. We therefore explore APs’ various levels of influence to identify the ethical foundations of their involvement and to demonstrate the relevance of integrating APs into clinical teams and the healthcare system.

3. Results

Our results include the characteristics of this study and findings related to our research questions.

3.1. Article Methodologies and Population (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies on the ethical foundation of the AP role.

The articles were published in the period 2015 to 2019 and represented a total of 7 studies, with 1 study being published in 2 articles [16,17]. Various methodologies were used in 5 empirical qualitative studies [13,16,17,18,19,20], including a study published in 2 articles, 1 empirical mixed methodology [21] and 1 review, which based their arguments on literature and personal experiences as healthcare professionals practicing with APs [22]. These studies were conducted in four countries: 4 in Canada [13,19,21,22], 2 in France [16,17], 1 in Norway and Canada [18] and 1 in the United Kingdom [20]. As for the language of publication, 4 studies were in English (4 studies) [18,20,21,22] and 3 were in French (including the study published in 2 articles) [13,16,17,19].

Four terms were used to describe what we called the accompanying patients. The most-used term was a variation of peer support with “pair aidant [peer supporter]” (n = 2) [13,19], “peer support workers” (n = 1) [20] and “peer support provider” (n = 1) [18] followed by “resource parent” because of the specific medical area of those studies (n = 2) [21,22] and “médiateur santé pair [peer health mediator]” (n = 1) [16,17].

The practice settings where the studies were conducted were psychiatry/mental health (n = 5) [13,16,17,18,19,20] and neonatology (n = 2) [21,22].

This review included the perspectives of patients [16,17,18,19,21], APs [13,16,17,18,19,21], healthcare professionals [18,19,20,21,22], healthcare managers [18,19] and policy makers [18].

3.2. Ethical Foundations Associated with the Personal Characteristics of Accompanying Patients

Three ethical foundations were identified in 6/8 papers to highlight the key personal ethical foundations associated with APs: resilience [13,19,21,22], listening skills [16], and altruism [18,21] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Personal ethical foundations of accompanying patients.

3.3. Foundations of the Relationship (Table 3)

Table 3.

Ethical foundations of the role of accompanying patients based on relationships.

3.3.1. With a Patient

We found 5 ethical foundations in 7/8 papers concerning the relationship with the patient, including hope [13,16,17,18,19,20,22], a reciprocal and egalitarian relationship with the advised patient [13,16,18,20], the autonomy of the patient advised [18], support [16,17,20], and real empathy [13,18,19,20].

3.3.2. With the Clinical Team

We found 6 ethical foundations in 6/8 papers concerning the relationship with the clinical team, including complementarity [18,20,21,22], collaboration [16,18,19,22], assertiveness [19,20], openness [19], respect [19], and respect of privacy [16].

3.3.3. With the Healthcare Setting

We found 6 ethical foundations in 6/8 papers used to describe the AP’s relationship with the healthcare setting: commitment [13,18,19,20,21,22], responsibility [13,18,19,20,22], versatility [13,19,20,22], recognition [13,22], health democracy [19], and transparency [13].

3.3.4. With the Patient and the Clinical Team

We found 2 ethical foundations in 3/8 papers concerning the relationship with the patient and the clinical team: confidentiality [13,18], and professionalism [16].

3.3.5. With the Clinical Team and the Healthcare Setting

We found 1 ethical foundation in 1/8 paper concerning the relationship with both the clinical team and the healthcare setting: collaboration [17].

3.3.6. With the Healthcare Setting and Society

We found 1 ethical foundation in 2/8 papers concerning the relationship with both the healthcare setting and society: collaboration [13,22].

4. Discussion

Over the last few decades, new roles and the involvement of patients in healthcare systems have led to the development of the AP role. While models such as the Montreal model have led the way to integrating these helping patients into clinical teams and healthcare settings [2], there are still unresolved ethical questions regarding this role. To address these challenges, there is a need to understand the ethical foundations of the AP role.

To our knowledge, this scoping review is the first to explore the ethical foundations of APs. It has revealed the underlying ethical foundations and there is a paucity of literature specifically addressing this emerging role. The studies were mostly conducted in Canada [13,18,19,21,22] and France [16,17], with only two conducted in Norway [18] and the United Kingdom [20].

The variety of vocabulary used demonstrates the lack of consensus around a term to describe the AP role and the influence of practice settings. In neonatology, the term resource parent is favoured [21,22]. This refers specifically to the parent role in their involvement with other health service users. Additionally, the variety of terms is symptomatic of the level of institutionalization of the AP role. The term “peer health mediator” is used specifically in France [16,17] and is directly linked to an institutionalized program of study [23]. Additionally, the Canadian mental health field favours the term “peer support” [13,18,19,20], which is a practice that has historically taken place outside of care settings.

Some authors have identified peer support values as “hope and recovery, self-determination, empathic and equal relationships, dignity, respect and social inclusion, integrity, authenticity and trust, health and wellness, lifelong learning and personal growth” [18] (p.68). This corroborates the proximity between peer support and the AP role and supports the results of this review.

4.1. Who Are the APs?

The foundations intrinsic to APs suggest the personal characteristics embedded in peer support practices. This role is merged with the common partnership model, known as the implication of patients in care, policies, research, and training, to motivate others to self-determination [18,23]. APs activate the key principles of partnership in other patients by using their experiential knowledge to improve well-being and motivate others to be part of their own care.

The involvement of APs enters into a logic of social exchange associated with selflessness [24], real empathy [13,18], destigmatizing illness [19,20] and encouraging patients to hope for recovery [13,16,17,18,19,20,22]. Embodying the hope of recovery, the AP is the materialization of the benefits and outcomes of the patient’s treatments or interventions. Indeed, the uncertainty of care processes and success is expected, but the presence of the AP serves to demonstrate that the care provided can work. This reinforces the patient’s confidence in the clinical team, the healthcare system and the care promulgated [25]. In this way, APs improve the relational chain of care within the healthcare system [14], thereby increasing the perceived quality of the care received [25]. In this sense, we support the idea that the form of exchange matters as much as its content.

4.2. What Is the Added Value of AP?

Mobilizing a personal experience of their life with illness, APs transform their knowledge into practical and technical tools to support patients. Listening skills and authenticity make APs more approachable and give patients the opportunity to share personal thoughts outside of their health concerns [17,20].

The complementarity and collaboration with the clinical team improves services [18,20,21]. As some professionals could perceive the addition of this new member as a failure to develop a professional relationship with patients and an overlap with their responsibilities [18,21], the AP role must be well defined by clearly differentiating the tasks and expectations for all concerned [13,18,19,20,21,22]. In this regard, healthcare settings have a responsibility to properly integrate APs, thereby ensuring their well-being, just as they do for staff members [13,20,22].

The unique perspective of APs enables health democratization [23] and full citizenship [19], since they symbolize the accessibility of health to everyone outside the healthcare system [23], notably because their knowledge differs from the theoretical outcomes [16].

4.3. What Are the Challenges for Institutionalization?

From a management perspective, healthcare systems play a leading role in the deployment and ethical support of APs. The literature presents a variety of models, including some in which APs take specific training within the education system and receive a salary [16,17,20,23], while in others, they suggest training from the healthcare institution and compensation can still be a thorny issue [13,18,19,21,22]. Some authors suggest that remuneration denatures the foundational AP role [13,22] and removes their independent voice [21]. However, our colleagues have analyzed the legal considerations around AP integration in the Québec, Canada healthcare system and concluded that, with or without remuneration, APs still have allegiance to the system [26]. Therefore, without any compensation—beyond being reimbursed for costs related to parking or public transportation, lunch, etc.—the lack of recognition is noticeable and does not capture a full picture of the allegiance dilemma.

Otherwise, APs in the PAROLE-Onco project have raised another ethical dilemma regarding allegiance. Regardless of their allegiance to the system, they may sometimes be in situations that make them feel that they must take the side of either the patient or the clinical team. At this time, this question has not been resolved, but it gives a sense of how allegiance can pose challenges and suggests that we need to take this ethical concern seriously.

This review has some limitations. Few studies were found on this subject. The lack of results demonstrates a gap in the literature that needs to be filled. Restricting the searches to English and French may have excluded relevant research published in other languages. Considering the variety of terms used to describe APs, it is possible that other terms, unknown to our research team, are also used for this role.

5. Conclusions

Even though we found few studies and little diversity in the methodologies used in the field, some more foundations of the AP role were identified, including resilience, listening skills and altruism. Future studies mobilizing stronger methodologies would help us understand how these foundations are applied in practice and how the results obtained in this review reflect APs’ experiences in healthcare systems.

We found that psychiatry/mental health and neonatology are two medical domains that directly address the ethical foundations of the AP role. Both fields engage in peer support and have demonstrated the applicability and added value of integrating APs into clinical teams and healthcare systems. The extant literature on ethics and patient partnership is more focused on research and training issues. However, the values and dilemmas seem to be quite similar among the various partnership models. In this regard, the next literature review should focus on the overall partnership instead of its separate areas.

More empirical studies are needed to further describe the values of the emerging AP role in order to better circumscribe the ethical foundations of this role.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G. and M.-P.P.; methodology, M.S., A.F. and M.-A.C.; validation, I.G. and M.-P.P.; formal analysis, M.S., I.G., M.-A.C., A.F. and M.-P.P.; investigation, M.S. and A.F.; resources, I.G. and M.-P.P.; data curation, M.-P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.F., I.G., M.-A.C. and M.-P.P.; supervision, I.G. and M.-P.P.; funding acquisition, M.-P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec, and the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation. MPP has received a Senior Career Award from the Quebec Health Research Fund (FRQS), the Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank Jim Kroening and Meghan O’Hanlon for their linguistic revision of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pomey, M.-P.; Dumez, V.; Denis, J.-L. Patient Engagement: How Patient-Provider Partnerships Transform Healthcare Organization; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pomey, M.-P.; Flora, L.; Karazivan, P.; Dumez, V.; Lebel, P.; Vanier, M.-C.; Débarges, B.; Clavel, N.; Jouet, E. Le « Montreal model »: Enjeux du partenariat relationnel entre patients et professionnels de la santé. Sante Publique 2015, S1, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bouabida, K.; Pomey, M.P.; Aho-Glele, U.; Gomes Chaves, B. The Paradoxical Injunctions of Partnership in Care: Patient Engagement and Partnership between Issues and Challenges. Patient Exp. J. 2021, 8, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, J.T.; Minyaoui, A.; Boivin, A. Partnering with Patients in Healthcare Research: A Scoping Review of Ethical Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations for Practice. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomey, M.-P.; Hihat, H.; Khalifa, M.; Lebel, P.; Néron, A.; Dumez, V. Patient Partnership in Quality Improvement of Healthcare Services: Patients’ Inputs and Challenges Faced. Patient Exp. J. 2015, 2, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, M.; Martineau, J.T.; Racine, E. Exploring Ethical Issues Related to Patient Engagement in Healthcare: Patient, Clinician and Researcher’s Perspectives. J. Bioethical Inq. 2019, 16, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullen Sansfaçon, A.; Cowden, S. The Ethical Foundations of Social Work; Routledge: New York, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M. A Narrative Approach to Health Psychology. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lierville, A.-L.; Grou, C.; Pelletier, J.-F. Enjeux éthiques potentiels liés aux partenariats patients en psychiatrie: État de situation à l’institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal. Santé Ment. Au Qué. 2015, 40, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Phanuel, D. La Charte d’accueil d’un Centre Hospitalier: Utiliser La Chaîne Relationnelle. Décisions Mark. 2001, 22, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.-L.; Pomey, M.-P. Engaging Patients to Improve Quality of Care: A Systematic Review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demailly, L.; Garnoussi, N. Les rencontres entre médiateurs de santé pairs et usagers de la psychiatrie en France: Caractéristiques générales et effets du dispositif sur les représentations des usagers. Partie 1. Santé Ment. Au Qué. 2015, 40, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demailly, L.; Garnoussi, N. Les rencontres entre médiateurs de santé pairs et usagers de la psychiatrie en France: Effets thérapeutiques, limites et impasses. Partie 2. Santé Ment. Au Qué. 2015, 40, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvale, G.; Wilson, F.; Jones, S.; Green, J.; Johansen, K.-J.; Arnold, I.; Kates, N. Integrating Mental Health Peer Support in Clinical Settings: Lessons from Canada and Norway. Healthc. Manage. Forum 2019, 32, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, M.-H.; Larue, C.; Côté, C. Contribution d’un pair aidant au retour post-isolement en santé mentale: Une étude qualitative exploratoire. Rev. Francoph. Int. Rech. Infirm. 2018, 4, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Firth, L.; Shakespeare, T. “Very Much Evolving”: A Qualitative Study of the Views of Psychiatrists about Peer Support Workers. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, S.; Bourque, C.J.; Reichherzer, M.; Ahmed, M.; Josée, P.; Mantha, G.; Labelle, F.; Janvier, A. Beyond a Seat at the Table: The Added Value of Family Stakeholders to Improve Care, Research, and Education in Neonatology. J. Pediatr. 2019, 207, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, C.J.; Dahan, S.; Mantha, G.; Robson, K.; Reichherzer, M.; Janvier, A. Improving Neonatal Care with the Help of Veteran Resource Parents: An Overview of Current Practices. Semin. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2018, 23, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardien, E.; Laval, C. The Institutionalisation of Peer Support in France: Development of a Social Role and Roll out of Public Policies. Eur. J. Disabil. Res. 2019, 13, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, J. L’esprit Du Don; La Découverte: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Phanuel, D. Confiance Dans Les Soins et Soin de La Confiance: La Réponse Relationnelle. Polit. Manag. Public 2002, 20, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutrouille, L.; Régis, C.; Pomey, M.-P. Enjeux Juridiques Propres Au Modèle Émergent Des Patients Accompagnateurs Dans Les Milieux de Soins Au Québec. Rev. Jurid. Thémis Univ. Montr. 2021, 55, 37. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).