Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was to report the evidence on optimal prandial timing of insulin bolus in youths with type 1 diabetes. A systematic search was performed including studies published in the last 20 years (2002–2022). A PICOS framework was used in the selection process and evidence was assessed using the GRADE system. Up to one third of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes injected rapid-acting insulin analogues after a meal. Moderate–high level quality studies showed that a pre-meal bolus compared with a bolus given at the start or after the meal was associated with a lower peak blood glucose after one to two hours, particularly after breakfast, as well as with reduced HbA1c, without any difference in the frequency of hypoglycemia. There were no differences related to the timing of bolus in total daily insulin and BMI, although these results were based on a single study. Data on individuals’ treatment satisfaction were limited but did not show any effect of timing of bolus on quality of life. In addition, post-prandial administration of fast-acting analogues was superior to rapid-acting analogues on post-prandial glycemia. There was no evidence for any difference in outcomes related to the timing of insulin bolus across age groups in the two studies. In conclusion, prandial insulin injected before a meal, particularly at breakfast, provides better post-prandial glycemia and HbA1c without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia, and without affecting total daily insulin dose and BMI. For young children who often have variable eating behaviors, fast-acting analogues administered at mealtime or post-meal could provide an additional advantage.

1. Introduction

Post-prandial hyperglycemia is a key factor influencing glycemic outcomes in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [1]. There are currently three rapid-acting insulin analogues on the market, and manufacturers recommend injecting insulin five to 10 minutes prior to a meal (Aspart) or up to 15 to 20 minutes after a meal (Lispro and Glulisine, respectively) [2,3,4]. In adults, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of rapid-acting insulin analogues [5] and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems data [6,7] showed that the injection of insulin 10 to 30 minutes before a meal provides optimal post-prandial glycemia [8]. Other studies in adults showed that the post-prandial spike is more effectively controlled by proper timing of insulin administration rather than increasing the pre-meal insulin dose or administering a super-sized correction bolus, which could result in hypoglycemia [9]. Inaccurate insulin bolus timing has been shown to result in suboptimal glycemic control in people with T1D [1]. Fast-acting analogues are now available on the market, and they have an onset of action approximately five to seven minutes earlier, and a glucose lowering effect 78–147% higher, than rapid-acting analogues [10], and they should provide more flexibility in the timing of the insulin bolus.

Timing of bolus is critical even when advanced insulin technologies are used. Data from advanced hybrid closed loop (AHCL) systems clearly show that the timing of bolus remains critical to achieve optimal glycemic targets, and a delayed administration may cause automated over-delivery of insulin and subsequent hypoglycemia [11]. In fact, even with the use of algorithms, refinements to mealtime boluses are necessary in order to control prandial glycemic excursions [11]. Smart pens, which record and store data on the amount and timing of recent insulin injections, provide dose reminder alerts, and the option to view active insulin on board, may facilitate and improve diabetes management and support people with T1D in achieving better timing of insulin boluses, particularly if combined with CGM use [12]. However, there is not enough supportive strong evidence for any of the bolus timing strategies, likely because significant interindividual and intraindividual variations exist in post-prandial glucose peak times [13]. A previous review on optimal prandial timing of bolus insulin concluded that in adults with T1D, the administration of rapid-acting insulin analogues 15–20 min before a meal led to a 30% reduction in post-meal glucose levels and rates of hypoglycemia compared with a bolus given immediately before a meal [8]. Improving post-meal glycemia is important as this will result in better HbA1c levels [14].

In the pediatric population, rapid-acting insulin analogues are now widely used, but there is no clear consensus on the optimal timing of bolus and whether this varies according to age. Given the recent introduction of fast-acting analogues, it would also be important to have an overview of the evidence of the optimal timing of bolus for these new insulin formulations. The aim of this systematic review is to provide an up-to-date summary of the available evidence on optimal prandial timing of insulin boluses in the pediatric population with T1D and its effect on glycemic outcomes and on treatment satisfaction.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Data for the present review were collected through searches of Pubmed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Clinicaltrial.gov, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Articles published between 1 January 2002 and 30 September 2022 were considered. Search terms, or “MESH” (Medical Subject Headings) used different combinations of terms: “insulin timing” or “time of dose” or “timing of bolus” or “timing of prandial” or “insulin-meal interval” AND “Type 1 diabetes” or “T1D” “insulin dependent” AND “post-prandial hyperglycemia” or “post-prandial excursion” or “metabolic control” or “glucose level” or “hypoglycemia” or “total daily insulin” or BMI or “treatment satisfaction”.

2.2. Criteria for Study Selection

We conducted a systematic search of the literature according to the PICOS model (population, intervention, comparison, results, study design):

| Population | Children and adolescents (1–18 years) with T1D. |

| Intervention | Insulin bolus given immediately before meal (START: ‒2 to 0 min) or post-meal (POST: 10–20 min after the start of the meal) Rapid analogue insulin bolus or mealtime (START) or post-meal (POST) fast-acting insulin analogue bolus. |

| Comparison | Pre-meal bolus (‒20 to ‒10 min), the gold standard in adults. |

| Outcomes | (i) post-prandial glucose levels, blood glucose area under the curve (AUC), maximum blood glucose level; (ii) HbA1c, number of hypoglycemic episodes, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episodes, total daily insulin dose, time in range, time below range; (iii) BMI; (iv) treatment satisfaction. |

| Study design | Randomized clinical trials (RCTs), observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies), exploratory studies, mix of qualitative and quantitative studies. |

The inclusion criteria in this systematic review included (i) youths aged 1–18 year with T1D; (ii) observational studies, exploratory studies, mix of qualitative and quantitative studies; (iii) we excluded review articles, after their reference lists screening to identify potential eligible studies; (iv) only full text papers were included, whereas abstract only were not included; (v) data on intervention (different timing of pre-meal bolus) (vi) publication date in the last 20 years (1 January 2003–30 September 2022).

Exclusion criteria were: (i) data available only for adults ≥18 years; (ii) case reports; studies with <10 children or adolescents with T1D; (iii) full paper not available; (iv) study not yet published; (v) studies not reporting different timing of bolus dose; (vi) languages other than English were not “a priori” exclusion criteria.

2.3. Data Extraction and Management

Two review authors (EM and RF) independently screened for inclusion the title and abstract of all the studies identified using the search strategy, with any disagreement resolved by a third reviewer (MLM). After abstract selection, 4 investigators conducted the full paper analysis.

The following characteristics were reviewed for each included study: (i) reference aspects: authorship(s); published or unpublished; year of publication; year in which the study was conducted; other relevant cited papers; (ii) study characteristics: study design, type of rapid or fast-acting insulin analogue and modality of bolus delivery, timing of bolus; (iii) population characteristics: age, number of pediatric participants with T1D, setting, treatment regimen, meal duration, meal composition, period, region; (iv) methodology: pre-prandial glucose targets, frequency of glucose monitoring, bolus timing: (v) main results: assessment of post-prandial glucose levels, HbA1c, patient and parent’s satisfaction.

2.4. Assessment of the Certainty of the Evidence

Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) was used to assess the certainty of evidence (www.gradeworkinggroup.org, accessed on 22 October 2022) for the included studies. GRADE was independently completed by 2 review authors (EM, RF) and the quality of evidence was rated for each of the outcomes above reported. In the case of risk bias in the study design, imprecision of estimates, inconsistency across studies, indirectness of the evidence, and publication bias, the option of decreasing the level of certainty by 1 or 2 levels according to the GRADE guidelines was applied [15]. GRADE has 4 levels of quality of evidence: very low, low, moderate, and high.

| High | The authors have a lot of confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect. |

| Moderate | The authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect. |

| Low | The true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect. |

| Very low | The true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect. |

3. Evidence from Clinical Studies

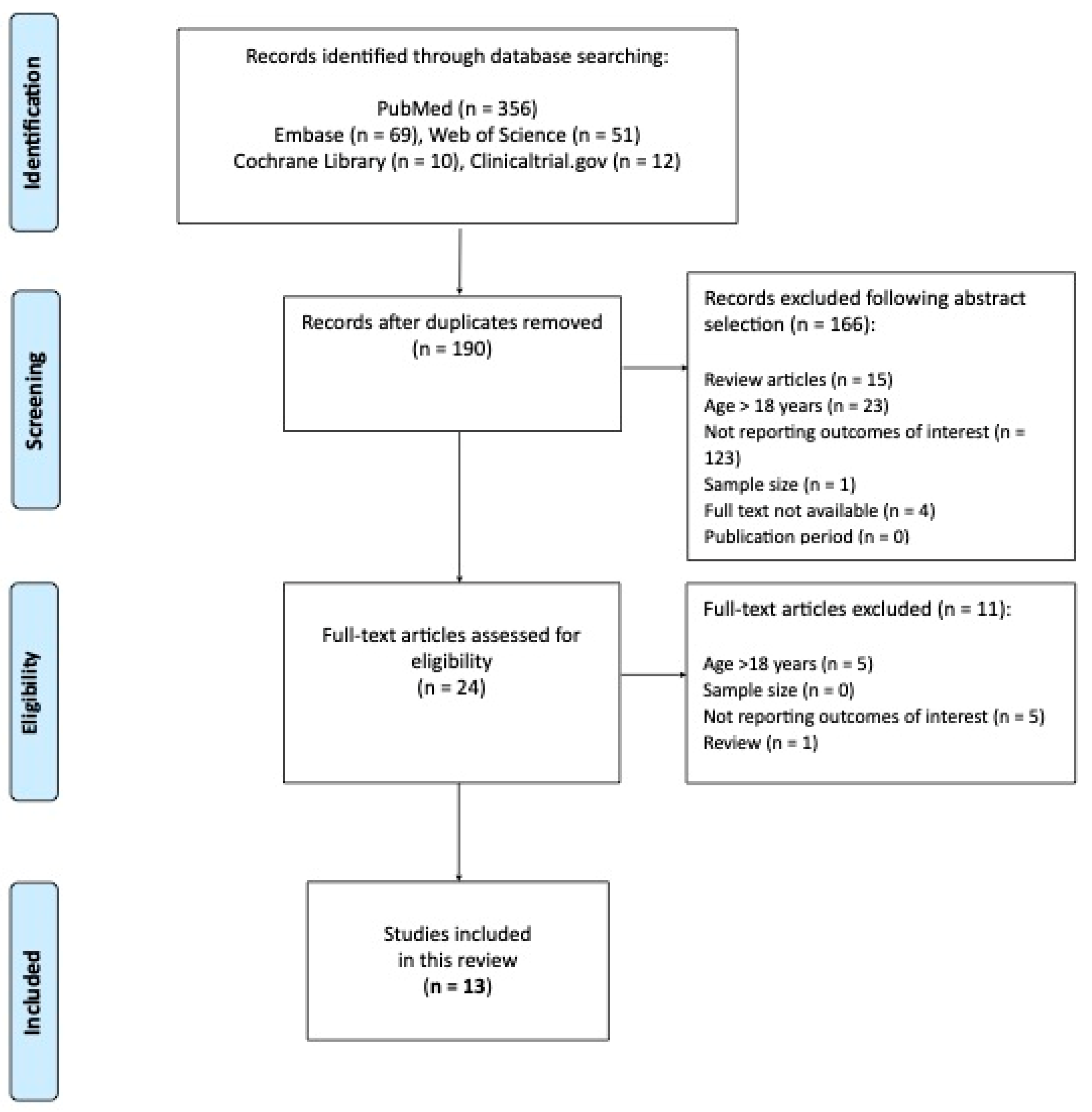

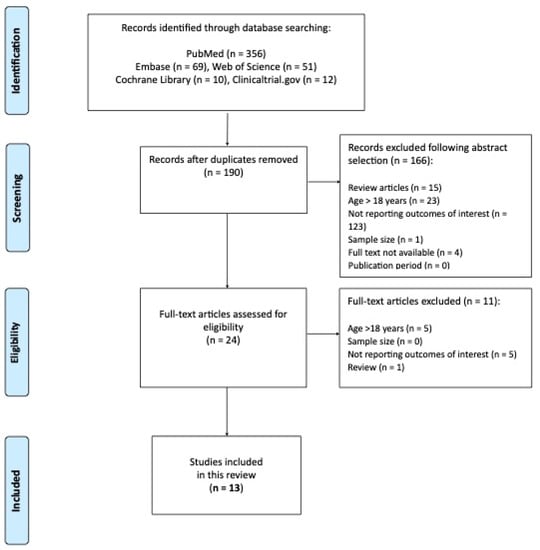

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the process of publications screening.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

A final number of 13 studies were included in this systematic review. A summary of studies along with the grading of evidence are reported in Table 1 [10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Table 1.

Literature analysis after PICOS selection: description, summary of the studies and grading of evidence using the GRADE system. PRE: −20 to −10 min before the meal; START: −2 to 0 min; POST: 10–20 min after the start of the meal.

According to moderate–high level quality studies, these are the main results:

3.1. Glycemic Outcomes

Post-prandial blood glucose: Administration of rapid-acting analogues a few minutes before, compared with immediately before or after the meal, leads to a smaller peak blood glucose at one hour after lunch [27] and up to two hours after breakfast [16,17]. No differences in these glycemic parameters were found between children and adolescents [17]. Time to reach post-meal glucose peak was longer when using a pre-meal bolus 20′ before a carbohydrate-rich meal compared with a similar bolus at the beginning of the meal [21]. Only one study reported data on time above range (TAR) and showed that a pre-meal bolus was associated with a better TAR compared with a bolus at the beginning or after the meal [16].

Fast-acting analogues administered at mealtime or post-meal, compared with rapid insulin analogues, provided an additional advantage in terms of reduced post-meal blood glucose peaks in one pediatric study, using fast-acting insulin aspart (FIAsp) [10], and in another using ultra-rapid lispro (URLi) [26]. Blood glucose was lower at one hour post-meal in two studies [24,26], and up to two hours in children, but not in adolescents, with T1D [10].

HbA1c and hypoglycemia: Some studies reported a better HbA1c in individuals who injected rapid-acting insulin analogue before a meal compared to immediately before or after, with no differences in risk of hypoglycemia [16,17,22,27], or even a reduced risk as reported in the study by Peters et al. [20]. These data are very important because, particularly in the pediatric population, giving insulin before a meal is associated with parental concerns about risk of hypoglycemia [20]. Another study did not show any difference in HbA1c associated with timing of bolus in children nor in adolescents [17].

In one study, the use of a fast-acting analogue (FIASP) administered at mealtime or post-meal, to cover a standardized liquid meal, compared with pre-meal rapid insulin analogues, led to better HbA1c results without increasing hypoglycemia [24]. However, another study assessing the fast-acting URLi compared with rapid-acting analogue, to cover real life meals, did not show any difference in HbA1c whereas hypoglycemia (blood glucose <54 mg/dL) two hours post-meal was increased [26].

Other benefits: A pre-meal standard bolus when eating an Italian ‘‘margherita’’ pizza was associated with a reduced zero to six hour glucose area under the curve, without an increase in hypoglycemia, and no differences in post-prandial blood glucose (PBG) and blood glucose (BG) peak was detected [23]. In an adolescent cohort of adolescents with T1D, pre-meal insulin bolus was associated with a reduced prevalence of missed bolus. This is an important finding given that missing even one meal insulin dose per week is associated with suboptimal glycemia and increased risk of DKA [22].

3.2. Total Daily Insulin Dose and BMI

One study with rapid-acting analogues showed that post-meal insulin bolus was associated with a higher total daily insulin dose and BMI compared to a bolus given pre-meal or at the same time as the meal in young people with T1D aged 12–18 years [20]. In contrast, no differences in these parameters were found in another study comparing the fast-rapid-acting analogue FIAsp given at mealtime and post-meal FIAsp with mealtime IAsp [24].

3.3. Treatment Satisfaction

Treatment satisfaction was analyzed only in one study, which reported no differences associated with timing of bolus, as well as no differences when analyzing data separately for children and adolescents [17].

4. Discussion

This systematic review provides an updated summary of current evidence, graded with the GRADE approach, on timing of insulin boluses in the pediatric population. In 2017, Slattery et al. conducted a systematic review on this topic in adults, and concluded that a rapid-acting insulin analog injected 15–20 min before a meal was associated with a ~30% reduction in post-meal glucose levels compared with when injected immediately before the meal [8]. Moreover, a greater risk of post-prandial hypoglycemia was detected when patients injected rapid-acting analogues after compared with before eating [8].

This systematic review shows that one third of children and adolescents inject rapid-acting analogues after a meal [20,22], despite the ISPAD 2018 recommendation of pre-meal injection [1]. Potential explanations for this observation are that post-meal insulin administration might facilitate a better evaluation of the carbohydrates consumed by the child, reduces parental concerns about the risk of hypoglycemia due to delayed or partial consumption of the meal, and could increase treatment satisfaction [20].

In this review, we analyzed selected studies considering three different bolus timings: pre-meal bolus: −20 to −10 min before the meal; at start of the meal: −2 to 0 min; post-meal bolus: 10–20 min after the start of the meal.

According to moderate–high level quality studies, these are the main findings of this review:

- Similar to adults, in the pediatric population, individuals using pre-meal insulin injection showed better glycemic outcomes (post-prandial BG, HbA1c, and hypoglycemia) compared with those on post-meal injections.

- Studies on fast-acting analogues confirmed the feasibility of post-meal dosing, which could contribute to lower BG levels for two hours after the meal according to their pharmacokinetic properties [10].

- The available data on treatment satisfaction are insufficient to make any conclusion about a negative effect on quality of life associated with pre-meal compared to post-meal bolusing.

- Only a few studies reported CGM data, which are a very important tool to move towards a personalized approach for the timing of insulin boluses based on individual characteristics, age groups, and meal composition. CGM data also provides valuable information on the individual’s glucose trends (stable, increasing, or decreasing levels) to adapt insulin timing or dose and improve time in range (TIR) [28].

The main strengths of this review are the stringent inclusion criteria, the inclusion of studies covering a 20-year period, the application of the PICOS model for the selection of studies, and the GRADE system for evidence assessment. The limitations are the heterogeneity of the studies, in terms of sample size, age of the study population, and the included outcomes. Due to this heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was not possible. In addition, assessment of the outcomes according to age groups was not possible due to limited data. Another key limitation of the available studies is lack of glycemic outcomes based on CGM systems, which are essential to move towards a personalized timing of boluses according to age groups and individual characteristics. Future studies assessing timing of boluses using CGM are needed.

5. Conclusions

The results of this systematic review are in line with those from studies in adults with T1D, in showing that a pre-prandial bolus provided better post-prandial glycemia and HbA1c without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia, and without affecting total daily insulin dose and BMI. For young children who often have variable eating behaviors, fast-acting analogues administered at mealtime or post-meal [29] could provide an additional advantage [24,26].

Author Contributions

R.F., E.M. and M.L.M. conceptualized and designed the study; R.F. and E.M. screened abstracts; F.D.C., L.L., F.M.R., M.G. and A.R. conducted the full paper analysis; E.M. and R.F. independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for each of the outcomes; M.L.M. resolved discrepancies; R.F., E.M. and M.L.M. prepared the draft manuscript. M.L.M., M.L.M. reviewed the manuscript and all the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All databases generated for this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- DiMeglio, L.A.; Acerini, C.L.; Codner, E.; Craig, M.E.; Hofer, S.E.; Pillay, K.; Maahs, D.M. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018, Glycemic control targets and glucose monitoring for children, adolescents, and young adults with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo Nordisk A/S. NovoRapid Summary of Product Characteristics. 2011. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000258/WC500030372.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Eli Lilly. Humalog Summary of Product Characteristics. 2011. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000088/WC500050332.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Sanofi-Aventis. Apidra Summary of Product Characteristics. 2011. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000557/WC500025250.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Home, P.D. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rapid-acting insulin analogues and their clinical consequences. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran-Valdez, E.; Burge, M.R.; Broderick, P.; Shey, L.; Valentine, V.; Schrader, R.M.; Schade, D.S. Insulin timing: A patient-centered approach to improve control in type 1 diabetes. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettus, J.; Price, D.A.; Edelman, S.V. How patients with type 1 diabetes translate continuous glucose monitoring data into diabetes management decisions. Endocr. Pract. 2015, 21, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, D.; Amiel, S.A.; Choudhary, P. Optimal prandial timing of bolus insulin in diabetes management: A review. Diabet. Med. 2018, 35, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettus, J. Time to get serious about insulin timing. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fath, M.; Danne, T.; Biester, T.; Erichsen, L.; Kordonouri, O.; Haahr, H. Faster-acting insulin aspart provides faster onset and greater early exposure vs. insulin aspart in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughton, C.K.; Hartnell, S.; Allen, J.M.; Hovorka, R. The importance of prandial insulin bolus timing with hybrid closed-loop systems. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 1716–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, S.L.; Munshi, M.M.; Toschi, E. Can Smart Pens Help Improve Diabetes Management? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.D.; Gjerløv, I.; Christiansen, J.S.; Hejlesen, O.K. Interindividual and intraindividual variations in postprandial glycemia peak time complicate precise recommendations for self-monitoring of glucose in persons with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.H.; Chen, V.; Miller, K.M.; McGill, J.B.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Goland, R.S.; Harlan, D.M.; Largay, J.F.; Massaro, E.M.; Beck, R.W.; et al. Differences in the management of type 1 diabetes among adults under excellent control compared with those under poor control in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3573–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Cuello, C.; Akl, E.A.; Mustafa, R.A.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Thayer, K.; Morgan, R.L.; Gartlehner, G.; Kunz, R.; Katikireddi, S.V.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobry, E.; McFann, K.; Messer, L.; Gage, V.; VanderWel, B.; Horton, L.; Chase, H.P. Timing of meal insulin boluses to achieve optimal postprandial glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2010, 12, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danne, T.; Aman, J.; Schober, E.; Deiss, D.; Jacobsen, J.L.; Friberg, H.H.; Jensen, L.H.; ANA 1200 Study Group. A comparison of postprandial and preprandial administration of insulin aspart in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohilla, L.; Dayal, D.; Gujjar, N.; Walia, P.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, J. Mealtime bolus insulin dose timing in children with type 1 diabetes: Real-life data from a tertiary care centre in northern India. Acta Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, W.; Lambert, E.; George, J.; Rathor, N.; Thalange, N. Exploring the Burden of Mealtime Insulin Dosing in Adults and Children With Type 1 Diabetes. Clin. Diabetes 2021, 39, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Van Name, M.A.; Thorsted, B.L.; Piltoft, J.S.; Tamborlane, W.V. Postprandial dosing of bolus insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes: A cross-sectional study using data from the T1D Exchange registry. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucholski, K.; Sokołowska, M.; Tucholska, D.; Kamińska, H.; Jarosz-Chobot, P. Assessment of optimal insulin administration timing for standard carbohydrates-rich meals using continuous glucose monitoring in children with type 1 diabetes: A cross-over randomized study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datye, K.A.; Boyle, C.T.; Simmons, J.; Moore, D.J.; Jaser, S.S.; Sheanon, N.; Kittelsrud, J.M.; Woerner, S.E.; Miller, K.M.; T1D Exchange. Timing of Meal Insulin and Its Relation to Adherence to Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2018, 12, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, A.; Giani, E.; Iafusco, D.; Bosetti, A.; Macedoni, M.; Gazzarri, A.; Spiri, D.; Scaramuzza, A.E.; Zuccotti, G.V. Lowering postprandial glycemia in children with type 1 diabetes after Italian pizza “margherita” (TyBoDi2 Study). Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2011, 13, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, B.W.; Iotova, V.; Kovarenko, M.; Laffel, L.M.; Rao, P.V.; Deenadayalan, S.; Ekelund, M.; Larsen, S.F.; Danne, T. Efficacy and Safety of Fast-Acting Insulin Aspart Compared With Insulin Aspart, Both in Combination With Insulin Degludec, in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: The onset 7 Trial. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Horio, H.; Rathor, N.; Ekelund, M. Efficacy and safety of fast-acting insulin aspart versus insulin aspart in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes from Japan. Endocr. J. 2021, 28, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadwa, R.P.; Laffel, L.M.; Franco, D.R.; Dellva, M.A.; Knights, A.W.; Pollom, R.K. Efficacy and safety of ultra-rapid lispro versus lispro in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: The PRONTO-Peds trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaramuzza, A.E.; Iafusco, D.; Santoro, L.; Bosetti, A.; De Palma, A.; Spiri, D.; Mameli, C.; Zuccotti, G.V. Timing of bolus in children with type 1 diabetes using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (TiBoDi Study). Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2010, 12, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemberton, J.S.; Barrett, T.G.; Dias, R.P.; Kershaw, M.; Krone, R.; Uday, S. An effective and cost-saving structured education program teaching dynamic glucose management strategies to a socio-economically deprived cohort with type 1 diabetes in a VIRTUAL setting. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise, T.; Hövelmann, U.; Brøndsted, L.; Adrian, C.L.; Nosek, L.; Haahr, H. Faster-acting insulin aspart: Earlier onset of appearance and greater early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects than insulin aspart. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2015, 17, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).