Identification of a Rare Novel KMT2C Mutation That Presents with Schizophrenia in a Multiplex Family

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Systemic Genome-Wide Mutations Scanning

2.3. Sanger Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

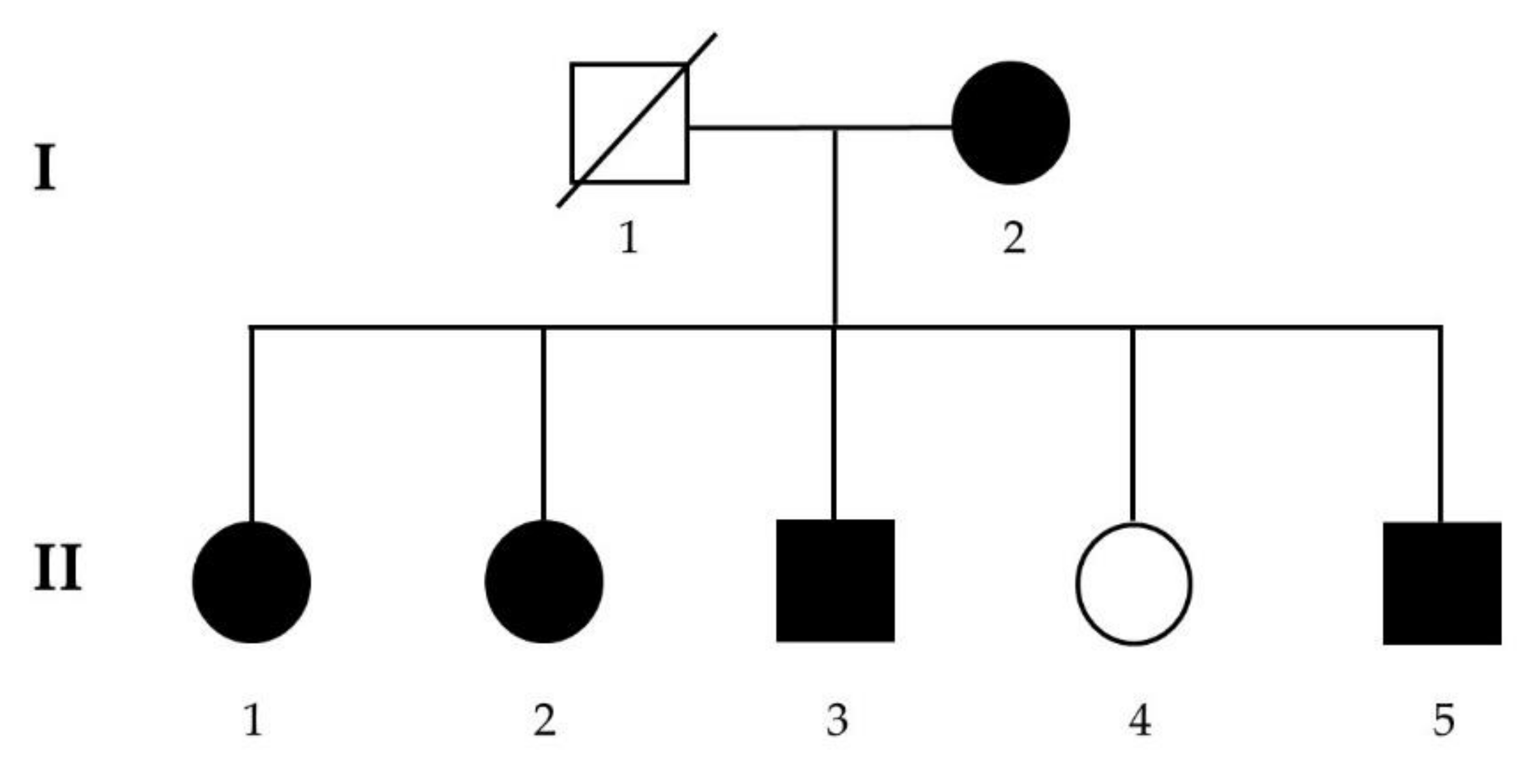

3.1. Recruitment of a Schizophrenia Multiplex Family

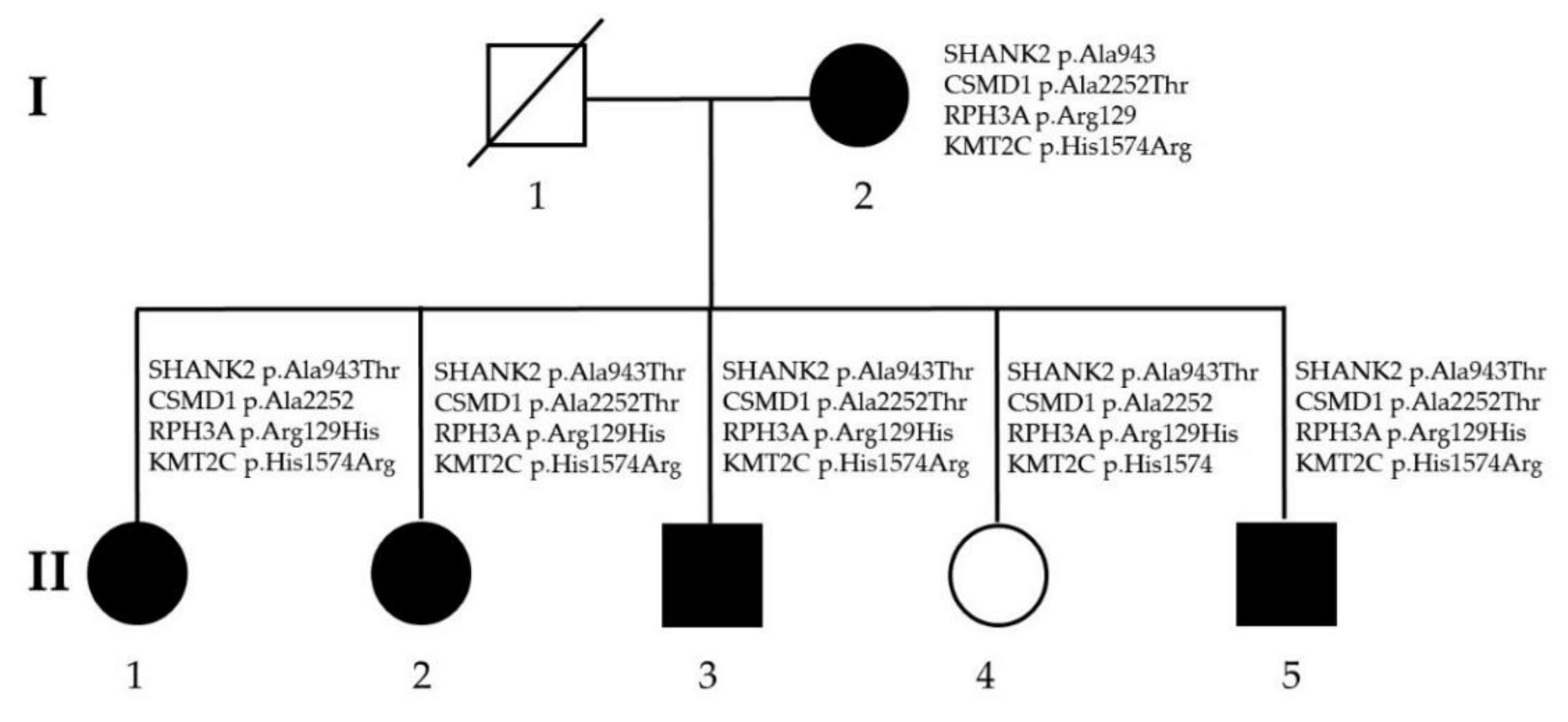

3.2. Identification of Rare, Likely Pathogenic Mutations

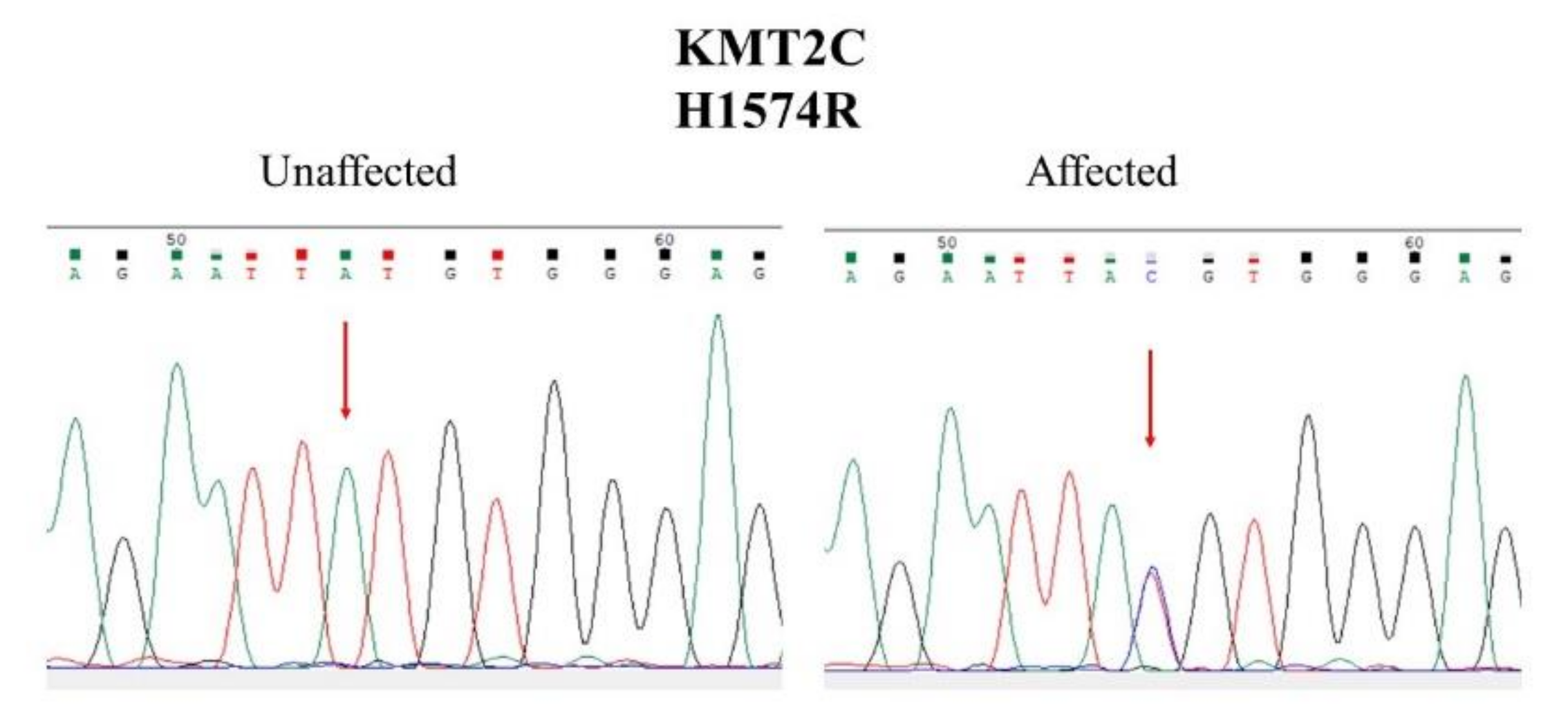

3.3. Sanger Sequencing and Segregation Analysis

3.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trifu, S.C.; Kohn, B.; Vlasie, A.; Patrichi, B.E. Genetics of schizophrenia (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 3462–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavari, B.; Cairns, M.J. Epigenomic Dysregulation in Schizophrenia: In Search of Disease Etiology and Biomarkers. Cells 2020, 9, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scionti, F.; Di Martino, M.T.; Pensabene, L.; Bruni, V.; Concolino, D. The Cytoscan HD Array in the Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. High Throughput 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzey, D.; Evans, E.A.; Lieber, C. Understanding the Basics of NGS: From Mechanism to Variant Calling. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2015, 3, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, E.T.; Goldstein, D.B. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, D.H.; Thiagarajah, T.; Malloy, P.; Pickard, B.S.; Muir, W.J. Chromosome abnormalities, mental retardation and the search for genes in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neurotox Res. 2008, 14, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giegling, I.; Hosak, L.; Mossner, R.; Serretti, A.; Bellivier, F.; Claes, S.; Collier, D.A.; Corrales, A.; DeLisi, L.E.; Gallo, C.; et al. Genetics of schizophrenia: A consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Genetics. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 18, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.; Corvin, A.; Nakagome, S. Genetics of Schizophrenia: Ready to Translate? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.L.; Herrera, L.; Gaspar, P.A.; Nieto, R.; Maturana, A.; Villar, M.J.; Salinas, V.; Silva, H. Shifting the focus toward rare variants in schizophrenia to close the gap from genotype to phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijsman, E.M. The role of large pedigrees in an era of high-throughput sequencing. Hum. Genet. 2012, 131, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bailey-Wilson, J.E.; Wilson, A.F. Linkage analysis in the next-generation sequencing era. Hum. Hered. 2011, 72, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.C.; Van Rechem, C.; Whetstine, J.R. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: Establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, E.; Shulha, H.; Weng, Z.; Akbarian, S. Regulation of histone H3K4 methylation in brain development and disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos, C.N.; Iwase, S. Disrupted intricacy of histone H3K4 methylation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleefstra, T.; Kramer, J.M.; Neveling, K.; Willemsen, M.H.; Koemans, T.S.; Vissers, L.E.; Wissink-Lindhout, W.; Fenckova, M.; van den Akker, W.M.; Kasri, N.N.; et al. Disruption of an EHMT1-associated chromatin-modification module causes intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koemans, T.S.; Kleefstra, T.; Chubak, M.C.; Stone, M.H.; Reijnders, M.R.F.; de Munnik, S.; Willemsen, M.H.; Fenckova, M.; Stumpel, C.; Bok, L.A.; et al. Functional convergence of histone methyltransferases EHMT1 and KMT2C involved in intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iossifov, I.; O’Roak, B.J.; Sanders, S.J.; Ronemus, M.; Krumm, N.; Levy, D.; Stessman, H.A.; Witherspoon, K.T.; Vives, L.; Patterson, K.E.; et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature 2014, 515, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rubeis, S.; He, X.; Goldberg, A.P.; Poultney, C.S.; Samocha, K.; Cicek, A.E.; Kou, Y.; Liu, L.; Fromer, M.; Walker, S.; et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 2014, 515, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, D.; Pevsner, J. The Contribution of Mosaic Variants to Autism Spectrum Disorder. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senormanci, O.; Karakas Celik, S.; Valipour, E.; Dogan, V.; Senormanci, G. Determination of candidate genes involved in schizophrenia using the whole-exome sequencing. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2018, 119, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assiry, A.A.; Albalawi, A.M.; Zafar, M.S.; Khan, S.D.; Ullah, A.; Almatrafi, A.; Ramzan, K.; Basit, S. KMT2C, a histone methyltransferase, is mutated in a family segregating non-syndromic primary failure of tooth eruption. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.D.; Li, Q.R.; Xu, S.N.; Wei, F.J.; Ye, Z.J.; Cheng, J.K.; Chen, J.P. Exome sequencing identifies an MLL3 gene germ line mutation in a pedigree of colorectal cancer and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013, 121, 1478–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Guipponi, M.; Santoni, F.A.; Setola, V.; Gehrig, C.; Rotharmel, M.; Cuenca, M.; Guillin, O.; Dikeos, D.; Georgantopoulos, G.; Papadimitriou, G.; et al. Exome sequencing in 53 sporadic cases of schizophrenia identifies 18 putative candidate genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Kurki, M.I.; Curtis, D.; Purcell, S.M.; Crooks, L.; McRae, J.; Suvisaari, J.; Chheda, H.; Blackwood, D.; Breen, G.; et al. Rare loss-of-function variants in SETD1A are associated with schizophrenia and developmental disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, A.; Xu, B.; Ionita-Laza, I.; Roos, J.L.; Gogos, J.A.; Karayiorgou, M. Loss-of-function variants in schizophrenia risk and SETD1A as a candidate susceptibility gene. Neuron 2014, 82, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| I-2 | II-1 | II-2 | II-3 | II-4 | II-5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 | 47 | 44 | 43 | 41 | 39 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| Education | Primary school | Primary school | Junior high school | Junior high school | Junior high school | Junior high school |

| Marital status | Married | Unmarried | Unmarried | Unmarried | Married | Unmarried |

| Diagnosis | Schizophrenia | Schizophrenia | Schizophrenia | Schizophrenia | Normal | Schizophrenia |

| Age of onset (years) | 20 | 20 | 24 | 22 | 22 | |

| Main psychotic symptoms | Self-talking, auditory hallucination, persecutory delusion | Self-talking, auditory hallucination, unstable mood | The idea of reference, persecutory delusion, irrelevant speech | Auditory hallucination, religious and persecutory delusions | Auditory hallucination, persecutory delusion | |

| Social function | Poor, staying in a chronic mental hospital | Poor, staying in a chronic mental hospital | Poor, staying in a chronic mental hospital | Poor, staying in a chronic mental hospital | Good, holding a job | Poor, staying in a chronic mental hospital |

| Co-morbidity | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gene | Chromosome | Mutation | dbSNP | Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHANK2 | 11q13.3-q13. | NC_000011.9:g.70333379C>T NM_012309.4:c.2827G>A NM_012309.4:p.Ala943Thr (Alanine943Threonine) | rs781910453 | 0 in ALPHA and Taiwan biobank |

| CSMD1 | 8p23.2 | NC_000008.10:g.2966125C>T NM_033225.5:c.6754G>A NM_033225.5:p.Ala2252Thr (Alanine2252Threonine) | rs369177851 | 0.000087 in ALPHA and 0 in Taiwan biobank |

| RPH3A | 12q24.13 | NC_000012.11:g.113304599G>A NM_014954.3:c.386G>A NM_014954.3:p.Arg129His (Arginine129Histidine) | rs148899308 | 0 in ALPHA and 0.001648 in Taiwan biobank |

| KMT2C | 7q36.1 | NC_000007.13:g.151884872T>C NM_170606.2:c.4721A>G NM_170606.2:p.His1574Arg (Histidine1574Arginine) | rs199796552 | 0.000096 in ALPHA and 0.002 in Taiwan biobank |

| Mutation | Primer (5‘-3‘) | Ta (℃) | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHANK2 p.Ala943Thr | Forward: GCTGCTCTTGCCGCTGCTGCTGG Reverse: TACAGTCGGAATGCCGGCCCGCA | 60 | 246 |

| CSMD1 p.Ala2252Thr | Forward: ACAGGAAACGCTGGCCTCCAGTG Reverse: TGGCAACACAGCCCTCGAAACGG | 60 | 253 |

| RPH3A p.Arg129His | Forward: GGCTACGTTGCCATGCCTCCCAT Reverse: ACCTCTTAAGGCACCTCTTAAGC | 60 | 224 |

| KMT2C p.His1574Arg | Forward: AAGGCTTGTACCTGGCATCAGGA Reverse: TGTGTTTATGTGGACCCATGCAG | 60 | 257 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.-H.; Huang, A.; Huang, Y.-S.; Fang, T.-H. Identification of a Rare Novel KMT2C Mutation That Presents with Schizophrenia in a Multiplex Family. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121254

Chen C-H, Huang A, Huang Y-S, Fang T-H. Identification of a Rare Novel KMT2C Mutation That Presents with Schizophrenia in a Multiplex Family. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(12):1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121254

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chia-Hsiang, Ailing Huang, Yu-Shu Huang, and Ting-Hsuan Fang. 2021. "Identification of a Rare Novel KMT2C Mutation That Presents with Schizophrenia in a Multiplex Family" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 12: 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121254

APA StyleChen, C.-H., Huang, A., Huang, Y.-S., & Fang, T.-H. (2021). Identification of a Rare Novel KMT2C Mutation That Presents with Schizophrenia in a Multiplex Family. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(12), 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121254