Influence of ApoE Genotype and Clock T3111C Interaction with Cardiovascular Risk Factors on the Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Clinical Assessment

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessment

2.3. Apolipoprotein E ε4, Clock T3111C and Per2 C111G Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Clinical Assessment

3.2. Description of Sample at Follow-Up

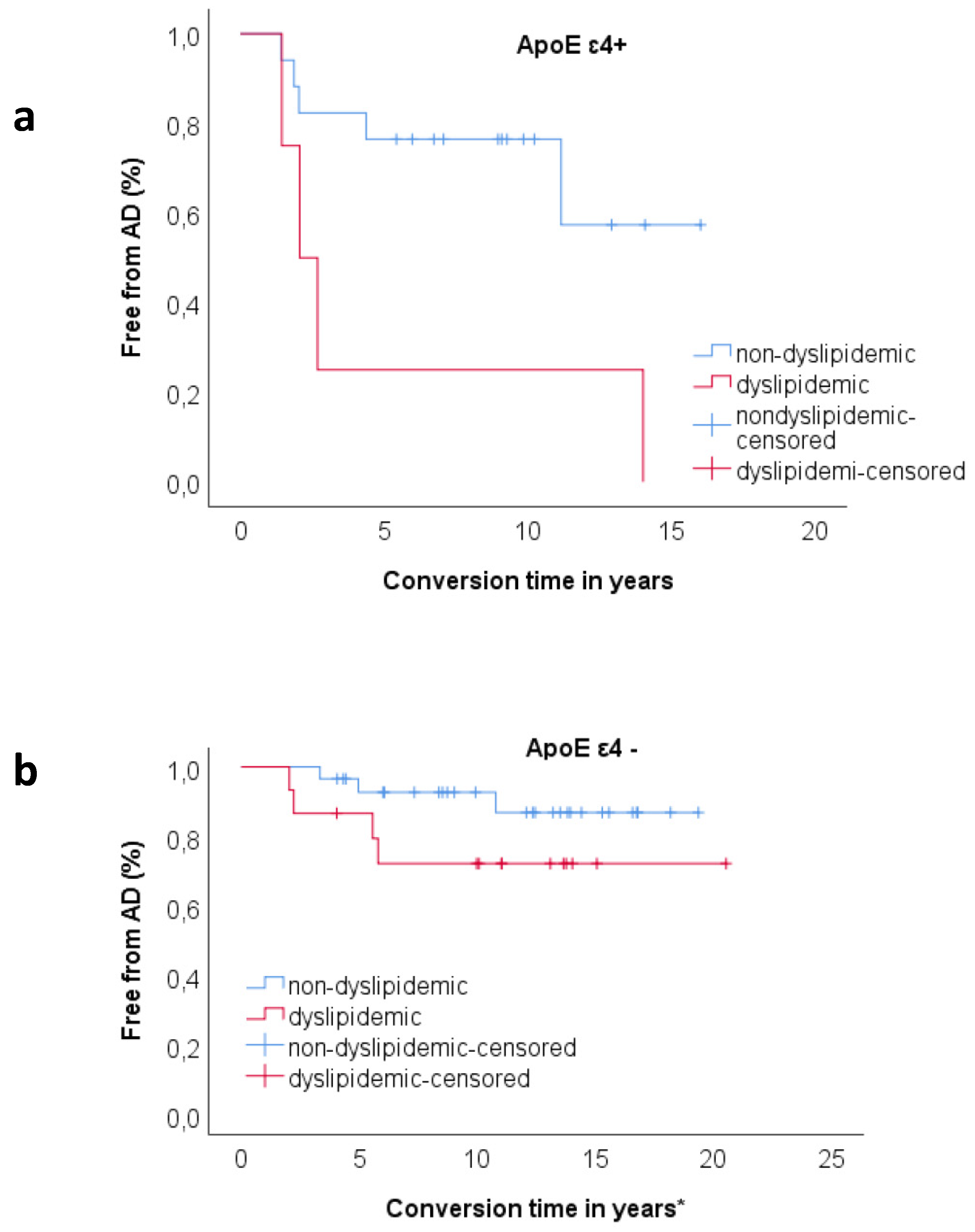

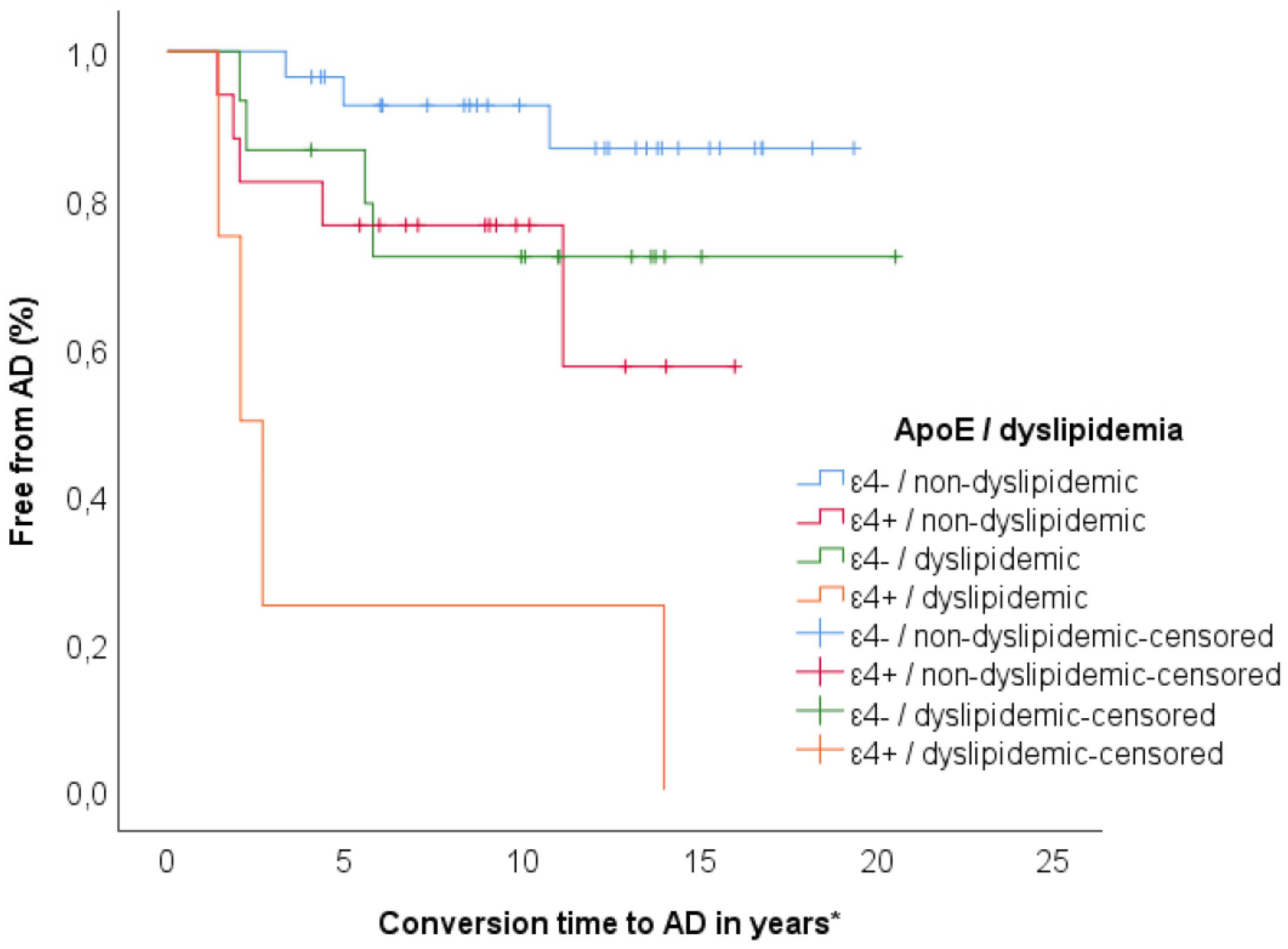

3.3. Relationship between ApoE and Dyslipidemia

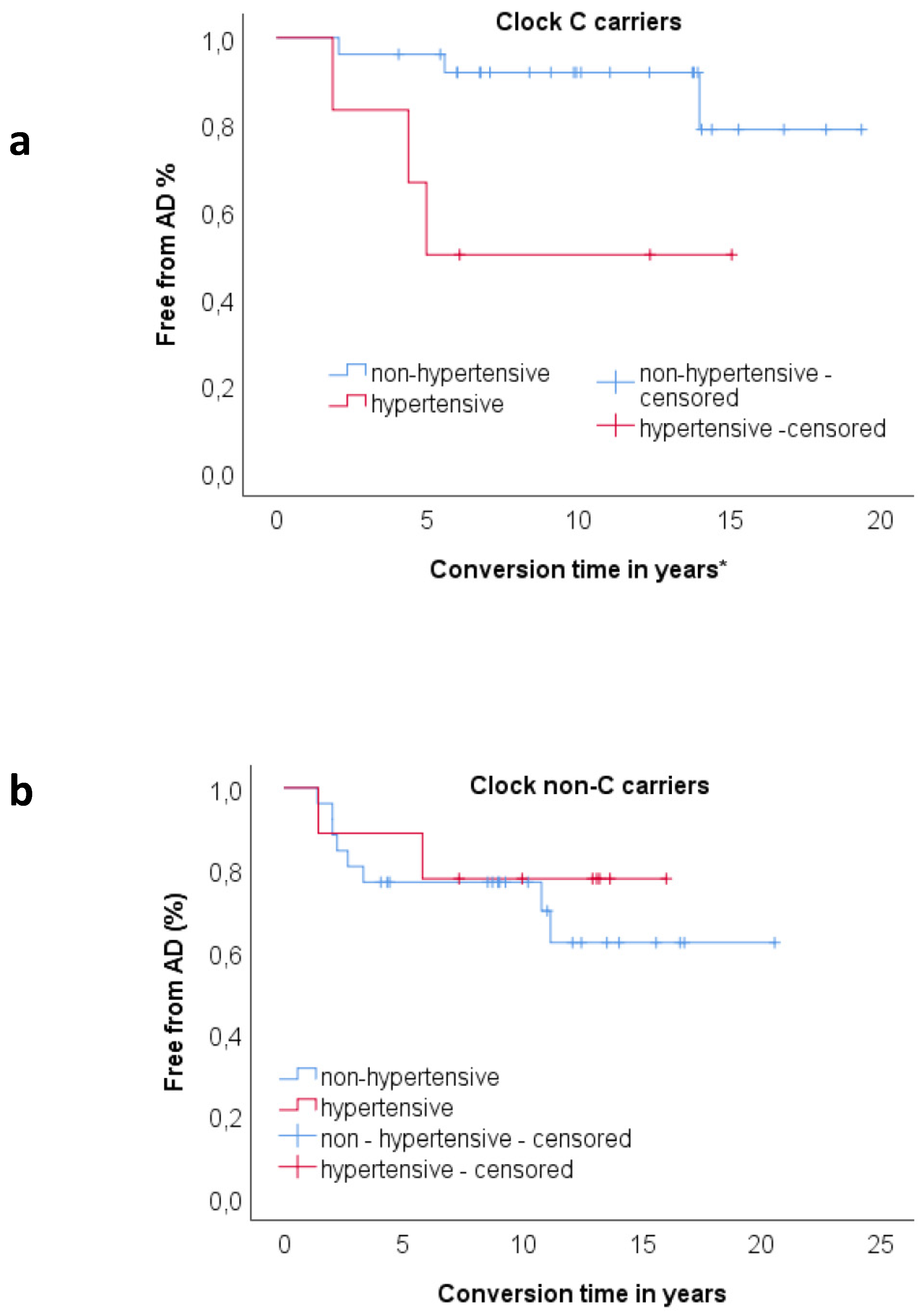

3.4. Relationship between Clock and Per2 and Risk Factors on Progression to AD

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Jack, C.R.; Kaye, J.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufouil, C.; Ellis, K.A.; van der Flier, W.M.; et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessi, V.; Mazzeo, S.; Padiglioni, S.; Piccini, C.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Bracco, L. From Subjective Cognitive Decline to Alzheimer’s Disease: The Predictive Role of Neuropsychological Assessment, Personality Traits, and Cognitive Reserve. A 7-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H.; Heffernan, M.; Kochan, N.A.; Draper, B.; Trollor, J.N.; Reppermund, S.; Slavin, M.J.; Sachdev, P.S. Mild cognitive impairment in a community sample: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013, 9, 310–317.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Beaumont, H.; Ferguson, D.; Yadegarfar, M.; Stubbs, B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: Meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichlen, D.A.; Bharadwaj, P.K.; Nguyen, L.A.; Franchetti, M.K.; Zigman, E.K.; Solorio, A.R.; Alexander, G.E. Effects of simultaneous cognitive and aerobic exercise training on dual-task walking performance in healthy older adults: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, K.; Nielson, K.A.; Smith, T.J.; Weiss, L.R.; Alfini, A.J.; Smith, J.C. Improved Cardiorespiratory Fitness Is Associated with Increased Cortical Thickness in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. JINS 2015, 21, 757–767. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, S.; Matthews, F.E.; Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K.; Brayne, C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazaly, E.; Charlesworth, J.; Dickinson, J.L.; Holloway, A.F. Genetic Determinants of Epigenetic Patterns: Providing Insight into Disease. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, R271–R277. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, S.; Amir, S. Neurodegeneration and the Circadian Clock. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Musiek, E.S.; Hu, K.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Yaffe, K. Association between circadian rhythms and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, S.; Kominsky, D.; Brodsky, K.; Eltzschig, H.; Walker, L.; Eckle, T. Cardiac Per2 functions as novel link between fatty acid metabolism and myocardial inflammation during ischemia and reperfusion injury of the heart. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Abellán, P.; Hernández-Morante, J.J.; Luján, J.A.; Madrid, J.A.; Garaulet, M. Clock genes are implicated in the human metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Sofi, F.; Dinu, M.; Sticchi, E.; Vannetti, F.; Molino Lova, R.; Ordovàs, J.M.; Gori, A.M.; Marcucci, R.; Giusti, B.; et al. CLOCK gene polymorphisms and quality of aging in a cohort of nonagenarians—The MUGELLO Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.; Snowden, J.S.; Gustafson, L.; Passant, U.; Stuss, D.; Black, S.; Freedman, M.; Kertesz, A.; Robert, P.H.; Albert, M.; et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998, 51, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; Decarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D.; et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, L.; Amaducci, L.; Pedone, D.; Bino, G.; Lazzaro, M.P.; Carella, F.; D’Antona, R.; Gallato, R.; Denes, G. Italian Multicentre Study on Dementia (SMID): A neuropsychological test battery for assessing Alzheimer’s disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1990, 24, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarra, P.; Vezzadini, G.; Dieci, F.; Zonato, F.; Venneri, A. Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: Normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 22, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Della Sala, S.; Papagno, C.; Spinnler, H. Dual-task performance in dysexecutive and nondysexecutive patients with a frontal lesion. Neuropsychology 1997, 11, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Spinnler, H.; Tognoni, G. Standardizzazione e Taratura Italian di Test Neuropsicologici: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio Neuropsicologico Dell’invecchiamento; Masson Italia Periodici: Milano, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli, A.R.; Del Pesce, M.; Mascheroni, S.; Simoncelli, M.; Laiacona, M.; Capitani, E. Trail making test: Normative values from 287 normal adult controls. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996, 17, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazzelli, M.; Della Sala, S.; Laiacona, M. Taratura della versione italiana del Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test: Un test di valutazione ecologica della memoria. Giunti Organ. Spec. 1993, 206, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, L.; Sartori, G.; Brivio, C. Stima del quoziente intellettivo tramite l’applicazione del TIB (Test Breve di Intelligenza). Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 2002, 29, 613–638. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, H. National Adult Reading Test (NART): For the Assessment of Premorbid Intelligence in Patients with Dementia: Test Manual; Windsor: Windsor, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, K.; Tozawa, T.; Satoh, K.; Saitoh, H.; Mishima, Y. The 3111T/C polymorphism of hClock is associated with evening preference and delayed sleep timing in a Japanese population sample. Am. J. Med Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005, 133, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Choub, A.; Mancuso, M.; Coppedè, F.; LoGerfo, A.; Orsucci, D.; Petrozzi, L.; DiCoscio, E.; Maestri, M.; Rocchi, A.; Bonanni, E.; et al. Clock T3111C and Per2 C111G SNPs do not influence circadian rhythmicity in healthy Italian population. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffroy, R.; Lafaye, G.; Desterke, C.; Ortiz-Tudela, E.; Amirouche, A.; Innominato, P.; Pham, P.; Benyamina, A.; Lemoine, A. Several clock genes polymorphisms are meaningful risk factors in the development and severity of cannabis addiction. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Krail, D.; McClung, C. Implications of circadian rhythm and stress in addiction vulnerability. F1000Research 2016, 5, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Perreau-Lenz, S.; Spanagel, R. Clock genes × stress × reward interactions in alcohol and substance use disorders. Alcohol 2015, 49, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessi, V.; Giacomucci, G.; Mazzeo, S.; Bagnoli, S.; Padiglioni, S.; Balestrini, J.; Tomaiuolo, G.; Piaceri, I.; Carraro, M.; Bracco, L.; et al. Per2 C111G polymorphism influences cognition in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment. A 10-year follow-up study. Eur. J. Neurol. under review.

- Bennet, A.M.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ye, Z.; Wensley, F.; Dahlin, A.; Ahlbom, A.; Keavney, B.; Collins, R.; Wiman, B.; de Faire, U.; et al. Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA 2007, 298, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.; Wang, D.; Long, J.; Yang, F.; Si, L. Meta-analysis of the association between whole grain intake and coronary heart disease risk. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B. Risk factors for vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. Stroke 2004, 35, 2620–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Flier, W.M.; Scheltens, P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, v2–v7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawle, M.J.; Davis, D.; Bendayan, R.; Wong, A.; Kuh, D.; Richards, M. Apolipoprotein-E (Apoe) ε4 and cognitive decline over the adult life course. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-L.; Caracciolo, B.; Wang, H.-X.; Santoni, G.; Winblad, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Accelerated progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia among APOE ε4ε4 carriers. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2013, 33, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.J.; Yoon, B.; Shim, Y.S.; Kim, S.-O.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Yang, D.W.; Lee, J.-H. Predictors of Clinical Progression of Subjective Memory Impairment in Elderly Subjects: Data from the Clinical Research Centers for Dementia of South Korea (CREDOS). Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 40, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, S.; Padiglioni, S.; Bagnoli, S.; Bracco, L.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Bessi, V. The dual role of cognitive reserve in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment: A 7-year follow-up study. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, T.S.; Rhea, E.M.; Banks, W.A.; Hanson, A.J. Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and apolipoprotein E interactions as mechanisms in cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1676–1683. [Google Scholar]

| Features | SCD | MCI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per2 G carriers–units (%) | 8 (19.5%) | 5 (18.5%) | 0.919 |

| Clock C carriers-units (%) | 21 (51.2%) | 11 (40.7%) | 0.397 |

| Per2 G carriers and Clock C carriers-units (%) | 4 (9.75%) | 3 (8.10%) | 0.843 |

| Features | Per2 | Clock | ApoE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non G (n = 55) | G (n = 13) | p | non C (n = 36) | C (n = 32) | p | ε4− (n = 45) | ε4+ (n = 23) | p | |

| SCD (% within SCD) | 80.5% | 19.5% | - | 48.8% | 51.2% | - | 68.3% | 31.7% | - |

| MCI (% within MCI) | 81.5% | 18.5% | - | 59.3% | 40.7% | - | 63% | 37% | - |

| Conversion to AD (SCD) (% in consideration of carrier status) | 0.0% | 25.0% | - | 5.0% | 4.8% | - | 3.6% | 7.7% | - |

| Conversion to AD (MCI) (% in consideration of carrier status) | 59.1% | 40.0% | - | 62.5% | 45.5% | - | 35.3% | 90% | - |

| Age at baseline (±SD) in years | 64.03 ± 9.12 | 65.22 ± 7.26 | 0.739 | 64.29 ± 9.33 | 63.69 ± 8.60 | 0.777 | 63.38 ± 9.08 | 65.38 ± 8.75 | 0.354 |

| Age at onset (±SD) in years | 59.69 ± 10.02 | 62.38 ± 7.96 | 0.562 | 60.56 ± 10.87 | 59.25 ± 8.64 | 0.694 | 59.38 ± 10.12 | 61.83 ± 9.17 | 0.228 |

| Follow-up time (±SD) in years | 10.87 ± 4.23 | 12.60 ± 4.68 | 0.234 | 11.34 ± 4.31 | 10.90 ± 4.45 | 0.815 | 13.00 ± 4.63 | 10.54 ± 4.71 | 0.065 |

| Disease duration (±SD) in years | 4.36 ± 3.63 | 2.83 ± 2.33 | 0.090 | 3.73 ± 3.65 | 4.44 ± 3.18 | 0.195 | 4.00 ± 4.85 | 3.55 ± 2.00 | 0.800 |

| Sex (females, males) | 37. 17 | 10. 3 | 0.552 | 26. 10 | 22. 10 | 0.754 | 33, 12 | 15, 8 | 0.487 |

| Family history of AD (%) | 61.11% | 15.38% | 0.003 * | 41.66% | 62.5% | 0.086 | 43.18% | 65.22% | 0.105 |

| Education in years (±SD) | 10.72 ± 4.55 | 7 ± 3.05 | 0.007 * | 9.86 ± 4.80 | 10.19 ± 4.21 | 0.737 | 9.73 ± 4.51 | 10.57 ± 4.54 | 0.455 |

| MMSE (±SD) | 28.46 ± 1.66 | 28.31 ± 1.49 | 0.583 | 28.09 ± 1.78 | 28.81 ± 1.33 | 0.064 | 28.34 ± 1.78 | 28.595 ± 1.26 | 0.839 |

| ApoE ε4 (%) | 35.18% | 23.07% | 0.404 | 30.55% | 37.5% | 0.546 | - | - | - |

| Diabetes (%) * | 5.60% | 7.70% | 0.770 | 8.30% | 3.10% | 0.362 | 2.20% | 13.00% | 0.730 |

| Hypertension (%) * | 22.20% | 23.10% | 0.947 | 25.00% | 18.8% | 0.535 | 22.20% | 21.70% | 0.964 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) * | 30.80%% | 23.10% | 0.585 | 30.60% | 26.70% | 0.728 | 34.10% | 18.20% | 0.178 |

| Heart Disease (%) * | 3.80% | 0.00% | 0.477 | 2.90% | 3.10% | 0.949 | 0.00% | 8.70% | 0.047 |

| Smoking (%) * | 11.30% | 7.70% | 0.703 | 2.80% | 19.40% | 0.027 | 6.80% | 17.40% | 0.179 |

| Features | Converters (n = 17) | Non Converters (n = 51) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence Per2 G (%) | 23.5% | 17.6% | 0.593 |

| Prevalence Clock C (%) | 35.3% | 51.0% | 0.262 |

| Age at baseline (±SD) in years | 70.7 (± 6.3) | 61.8 (±8.6) | <0.01 |

| Age at onset * (±SD) in years | 67.4 (± 7.5) | 57.9 (±9.4) | <0.01 |

| Follow-up time (±SD) in years | 9.6 (± 4.7) | 13.03 (±4.5) | <0.01 |

| Disease duration (±SD) in years | 3.3 (± 3.6) | 4.0 (±4.3) | 0.602 |

| Sex (females, males) | 12,5 | 36,15 | 1.000 |

| Family history of AD (%) | 52.9% | 51.0% | 0.889 |

| Education in years (±SD) | 8.4 (±3.9) | 10.6 (±4.6) | 0.059 |

| MMSE (±SD) | 28.1 (±1.1) | 28.5 (±1.8) | 0.399 |

| ApoE ε4 (%) | 58.8% | 25.5% | 0.012 |

| Hypertension (%) | 29.4% | 19.6% | 0.399 |

| Diabetes (%) | 11.8% | 3.9% | 0.234 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 47.1% | 22.4% | 0.053 |

| Heart disease (%) | 11.8% | 0.0% | 0.014 |

| Smoking (current) (%) | 0.0% | 14.0% | 0.103 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | - |

| B | p | HR | 95% C.I. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Whole sample | |||||

| ApoE e4 | 1.826 | 0.001 | 6.212 | 2.045 | 18.872 |

| Age at baseline | 0.151 | 0.001 | 1.163 | 1.067 | 1.269 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.126 | 0.041 | 3.083 | 1.045 | 9.099 |

| Clock C carriers | |||||

| Hypertension | 3.265 | 0.025 | 26.18 | 1.510 | 454.039 |

| Clock non C carriers | |||||

| Age at baseline | 0.204 | 0.002 | 1.23 | 1.078 | 1.394 |

| ApoE | 2.111 | 0.009 | 8.25 | 1.712 | 39.791 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bessi, V.; Balestrini, J.; Bagnoli, S.; Mazzeo, S.; Giacomucci, G.; Padiglioni, S.; Piaceri, I.; Carraro, M.; Ferrari, C.; Bracco, L.; et al. Influence of ApoE Genotype and Clock T3111C Interaction with Cardiovascular Risk Factors on the Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10020045

Bessi V, Balestrini J, Bagnoli S, Mazzeo S, Giacomucci G, Padiglioni S, Piaceri I, Carraro M, Ferrari C, Bracco L, et al. Influence of ApoE Genotype and Clock T3111C Interaction with Cardiovascular Risk Factors on the Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2020; 10(2):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10020045

Chicago/Turabian StyleBessi, Valentina, Juri Balestrini, Silvia Bagnoli, Salvatore Mazzeo, Giulia Giacomucci, Sonia Padiglioni, Irene Piaceri, Marco Carraro, Camilla Ferrari, Laura Bracco, and et al. 2020. "Influence of ApoE Genotype and Clock T3111C Interaction with Cardiovascular Risk Factors on the Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients" Journal of Personalized Medicine 10, no. 2: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10020045

APA StyleBessi, V., Balestrini, J., Bagnoli, S., Mazzeo, S., Giacomucci, G., Padiglioni, S., Piaceri, I., Carraro, M., Ferrari, C., Bracco, L., Sorbi, S., & Nacmias, B. (2020). Influence of ApoE Genotype and Clock T3111C Interaction with Cardiovascular Risk Factors on the Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 10(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10020045