The Role of Imaging Techniques in the Evaluation of Extraglandular Manifestations in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Imaging Evaluation of Systemic Manifestations in Sjögren’s Syndrome

| Systemic Manifestations | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Muscle involvement | <2 |

| Joint involvement | 53 |

| Pulmonary involvement | 23 |

| Central nervous system involvement | 10.8 |

| Systemic Involvement | Findings | Imaging Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Muscular | Myositis | Ultrasonography Elastography |

| Articular | Synovitis RC 1 joint MCP 2 joint PIP 3 joint Tenosynovitis Erosive arthritis | Ultrasonography |

| Pulmonary | Interstitial lung disease | High-resolution computed tomography |

| Central nervous system | Demyelinating lesions Neuromyelitis optica Pseudotumoral brain lesions | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Lymphoproliferative | Lymphoma | Ultrasonography Magnetic resonance imaging |

3.1. Imaging Evaluation of Muscle Involvement in Sjögren’s Syndrome

| Grade | Clinical Significance | Ultrasonographic Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | Hypoechoic muscle with a clearly visible bone cortex |

| 2 | Mild changes | Mild increase in muscle echogenicity, with a clearly visible bone cortex |

| 3 | Moderate changes | Marked increase in muscle echogenicity, with blurring of the bone cortex |

| 4 | Severe changes | Markedly hyperechoic muscle, with no visualization of the bone cortex |

3.2. Imaging Evaluation of Joint Involvement in Sjögren’s Syndrome

| Joints | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Radiocarpal | 30 |

| Metacarpophalangeal | 35 |

| Proximal interphalangeal | 35 |

| Grade | Synovitis | Synovial Hypertrophy on B-Mode US | Power Doppler Signal | Combined Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Absent | No SH 1, regardless of effusion | No PD 2 | No SH 1 or PD 2 |

| 1 | Minimal | SH 1 not extending beyond the horizontal line connecting the bony surfaces, regardless of effusion | ≤3 isolated spots ≤1 confluent spot + 2 isolated spots ≤2 confluent spots | SH 1 Grade 1 and PD 2 ≤ Grade 1 |

| 2 | Moderate | SH 1 extending beyond the joint line, with a linear or concave surface, regardless of effusion | >Grade 1, with PD 2 spots < 50% of the SH 1 area | SH 1 Grade 2 and PD 2 ≤ Grade 2 OR SH 1 Grade 1 and PD 2 Grade 2 |

| 3 | Severe | SH 1 extending beyond the joint line, with a convex surface, regardless of effusion | >Grade 2, with PD 2 spots > 50% of the SH 1 area | SH 1 Grade 3 and PD 2 ≤ Grade 3 OR SH 1 Grade 1 or 2 and PD 2 Grade 3 |

| Articular Involvement | Se 4 (%) | Sp 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Synovitis | ||

| RC 1 joint | 73 | 78 |

| MCP 2 joint | 64 | 93 |

| PIP 3 joint | 71 | 94 |

| Tenosynovitis | 86.5 | 100 |

| Erosive arthritis | 67.2 | 97.5 |

3.3. Imaging Evaluation of Pulmonary Involvement in Sjögren’s Syndrome

3.4. Imaging Evaluation of Central Nervous System Involvement in Sjögren’s Syndrome

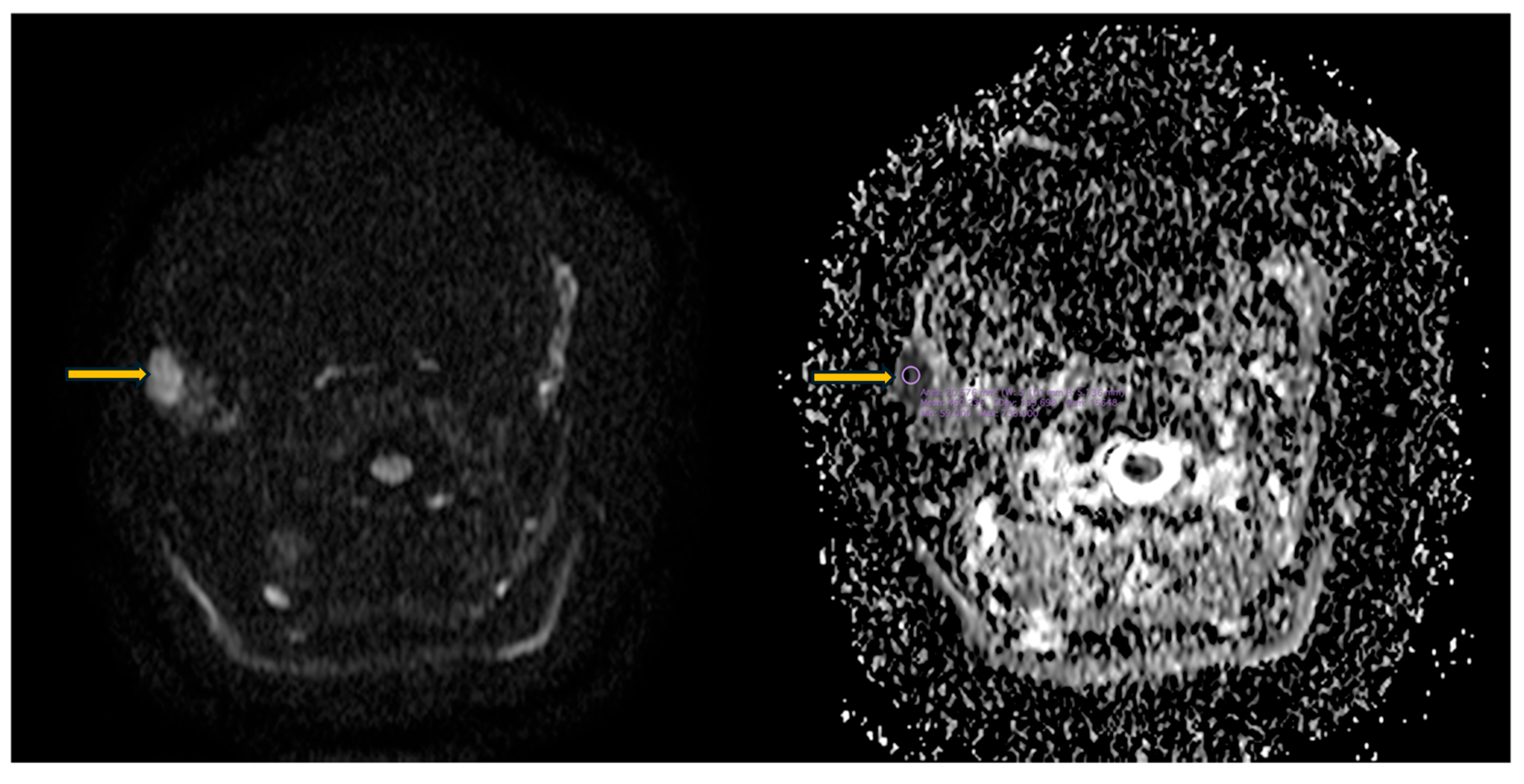

3.5. Imaging Evaluation of Lymphoproliferative Complications in Sjögren’s Syndrome

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR/EULAR | American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism |

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| Anti-SSA | anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ESSDAI | European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index |

| FLAIR | Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| HRCT | High-resolution computed tomography |

| IBM | Inclusion body myositis |

| LIP | Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia |

| MALT | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue |

| MCP | Metacarpophalangeal |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NSIP | Non-specific interstitial pneumonia |

| OMERACT | Outcome Measures in Rheumatology |

| OP | Organizing pneumonia |

| PD | Power Doppler |

| PIP | Interphalangeal |

| RC | Radiocarpal |

| SE | Strain elastography |

| SH | Synovial hypertrophy |

| STIR | Short tau inversion recovery |

| SWE | Shear-wave elastography |

| UIP | Usual interstitial pneumonia |

| US | Ultrasonography |

References

- André, F.; Böckle, B.C. Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 980–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Talarico, R.; Tzioufas, A.G.; Bombardieri, S. Primary Sjogren Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431049/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Negrini, S.; Emmi, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Murdaca, G.; Indiveri, F.; Puppo, F. Sjögren’s syndrome: A systemic autoimmune disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki-Fischbach, M.; Kastsianok, L.; Koslow, M.; Chan, E.D. Manifestations and management of Sjögren’s disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodba, A.; Ancuta, C.; Tatarciuc, D.; Ghiorghe, A.; Lodba, L.O.; Iordache, C. Comparative Analysis of Glandular and Extraglandular Manifestations in Primary and Secondary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Study in Two Academic Centers in North-East Romania. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabotti, A.; Zandonella Callegher, S.; Tullio, A.; Vukicevic, A.; Hocevar, A.; Milic, V.; Cafaro, G.; Carotti, M.; Delli, K.; De Lucia, O.; et al. Salivary Gland Ultrasonography in Sjögren’s Syndrome: A European Multicenter Reliability Exercise for the HarmonicSS Project. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 581248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horai, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Nakamura, H.; Kawakami, A. Recent Advances in Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Imaging, and Treatment of Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Y.; Wintermark, M.; Penta, M. Imaging characteristics of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Imaging 2022, 92, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, A.; Caruntu, C.; Jurcut, C.; Blajut, F.C.; Casian, M.; Opris-Belinski, D.; Ionescu, R.; Caruntu, A. The Spectrum of Extraglandular Manifestations in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, A.; Bruyn, G.A.; Terslev, L.; De Agustin, J.J.; MacCarter, D.; Chrysidis, S.; Collado, P.; Dejaco, C.; Fana, V.; Filippou, G.; et al. Development of a new ultrasound scoring system to evaluate glandular inflammation in Sjögren’s syndrome: An OMERACT reliability exercise. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 3341–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, A.; Coiffier, G.; Bleuzen, A.; Goasguen, J.; de Bandt, M.; Deligny, C.; Magnant, J.; Ferreira, N.; Diot, E.; Perdriger, A.; et al. What is the best salivary gland ultrasonography scoring methods for the diagnosis of primary or secondary Sjögren’s syndromes? Jt. Bone Spine 2019, 86, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, I.; Sakamoto, M.; Iikubo, M.; Kumamoto, H.; Muroi, A.; Sugawara, Y.; Satoh-Kuriwada, S.; Sasano, T. Diagnostic performance of MR imaging of three major salivary glands for Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, M.S.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; van der Vegt, B.; Mossel, E.; Kroese, F.G.M.; Bootsma, H.; Vissink, A. Imaging in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ferrada, M.A.; Hasni, S.A. Pulmonary Manifestations of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Underlying Immunological Mechanisms, Clinical Presentation, and Management. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.S.; Baer, A.N. Neurological Complications of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Treatm. Opt. Rheumatol. 2017, 3, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonami, H.; Matoba, M.; Kuginuki, Y.; Yokota, H.; Higashi, K.; Yamamoto, I.; Sugai, S. Clinical and imaging findings of lymphoma in patients with Sjögren syndrome. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2003, 27, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Chávez, A.; Kostov, B.; Solans, R.; Fraile, G.; Maure, B.; Feijoo-Massó, C.; Rascón, F.J.; Pérez Álvarez, R.; Zamora-Pasadas, M.; García-Pérez, A.; et al. Severe, life-threatening phenotype of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Clinical characterisation and outcomes in 1580 patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2018, 36, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Seror, R.; Gottenberg, J.E.; Devauchelle-Pensec, V.; Dubost, J.J.; Le Guern, V.; Hayem, G.; Fauchais, A.; Goeb, V.; Hachulla, E.; Hatron, P.Y.; et al. European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index and European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index: A Complete Picture of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seror, R.; Ravaud, P.; Bowman, S.J.; Baron, G.; Tzioufas, A.; Theander, E.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; Bootsma, H.; Mariette, X.; Vitali, C. EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity index: Development of a consensus systemic disease activity index for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felten, R.; Giannini, M.; Nespola, B.; Lannes, B.; Levy, D.; Seror, R.; Vittecoq, O.; Hachulla, E.; Perdriger, A.; Dieude, P.; et al. Refining myositis associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Data from the prospective cohort ASSESS. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Priori, R.; Gattamelata, A.; Picarelli, G.; Minniti, A.; Brancatisano, F.; D’Amati, G.; Giordano, C.; Cerbelli, B.; Maset, M.; et al. Myositis in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Data from a multicentre cohort. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015, 33, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Solans, R.; Camps, M.T.; Casanovas, A.; Sopeña, B.; Diaz-Lopez, B.; Rascon, F.-J.; Qanneta, R.; Fraile, G.; et al. Systemic involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome evaluated by the EULAR-SS disease activity index: Analysis of 921 Spanish patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Rheumatology 2014, 53, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardicurti, O.; Marino, A.; Genovali, I.; Navarini, L.; D’Andrea, S.; Currado, D.; Rigon, A.; Arcarese, L.; Vadacca, M.; Giacomelli, R. Interstitial Lung Disease and Pulmonary Damage in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, A.M.; Moog, P.; Kalluri, S.R.; Hofauer, B.; Knopf, A.; Kirschke, J.S.; Hemmer, B.; Berthele, A. CNS demyelinating events in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A single-center case series on the clinical phenotype. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1128315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konen, F.F.; Güzeloglu, Y.E.; Seeliger, T.; Jendretzky, K.F.; Nay, S.; Grote-Levi, L.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Gründges, C.; Ernst, D.; Witte, T.; et al. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy associated with Sjögren’s disease: Features of a distinct clinical entity. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1654576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Thibault, A.; Masseau, A.; Néel, A.; Espitia, O.; Toquet, C.; Mussini, J.M.; Hamidou, M. Sjögren’s syndrome-associated myositis with germinal centre-like structures. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, M.; Felten, R.; Gottenberg, J.E.; Geny, B.; Meyer, A. Inclusion body myositis and Sjögren’s syndrome: The association works both ways. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwenberg, K.E.; van Alfen, N.; Christopher-Stine, L.; Paik, J.J.; Tiniakou, E.; Mecoli, C.; Doorduin, J.; Saris, C.G.; Albayda, J. Ultrasound can differentiate inclusion body myositis from disease mimics. Muscle Nerve 2020, 61, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasca, G.; Monforte, M.; De Fino, C.; Kley, R.A.; Ricci, E.; Mirabella, M. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern recognition in sporadic inclusion-body myositis. Muscle Nerve 2015, 52, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visser, M.; Carlier, P.; Vencovský, J.; Kubínová, K.; Preusse, C.; Albayda, J.; Allenbach, Y.; Benveniste, O.; Diederichsen, L.; Demonceau, G.; et al. 255th ENMC workshop: Muscle imaging in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. 15th January, 16th January and 22nd January 2021—Virtual meeting and hybrid meeting on 9th and 19th September 2022 in Hoofddorp, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2023, 33, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayda, J.; van Alfen, N. Diagnostic Value of Muscle Ultrasound for Myopathies and Myositis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaby, R.; Mohamed, K.A.; Elgenidy, A.; Sonbol, Y.T.; Bedewy, M.M.; Aboutaleb, A.M.; Ebrahim, M.A.; Maallem, I.; Dardeer, K.T.; Heikal, H.A.; et al. Muscle Sonography in Inclusion Body Myositis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 944 Measurements. Cells 2022, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmatt, J.Z.; Leeman, S.; Dubowitz, V. Ultrasound imaging in the diagnosis of muscle disease. J. Pediatr. 1982, 101, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botar-Jid, C.; Damian, L.; Dudea, S.M.; Vasilescu, D.; Rednic, S.; Badea, R. The contribution of ultrasonography and sonoelastography in assessment of myositis. Med. Ultrason. 2010, 12, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Alfuraih, A.M.; O’Connor, P.; Tan, A.L.; Hensor, E.M.A.; Ladas, A.; Emery, P.; Wakefield, R.J. Muscle shear wave elastography in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A case-control study with MRI correlation. Skelet. Radiol. 2019, 48, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Seror, R.; Bootsma, H.; Bowman, S.J.; Dörner, T.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; Mariette, X.; Theander, E.; Bombardieri, S.; et al. Characterization of systemic disease in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations for articular, cutaneous, pulmonary and renal involvements. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carubbi, F.; Alunno, A.; Conforti, A.; Riccucci, I.; Di Cola, I.; Bartoloni, E.; Gerli, R. Characterisation of articular manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Clinical and imaging features. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura, T.; Fujimoto, T.; Hara, R.; Shimmyo, N.; Kobata, Y.; Kido, A.; Akai, Y.; Tanaka, Y. Subclinical articular involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome assessed by ultrasonography and its negative association with anti-centromere antibody. Mod. Rheumatol. 2015, 25, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase-Minegishi, K.; Horita, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Yoshimi, R.; Kirino, Y.; Ohno, S.; Kaneko, T.; Nakajima, H.; Wakefield, R.J.; Emery, P. Diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound for synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, M.A.; Terslev, L.; Aegerter, P.; Backhaus, M.; Balint, P.; Bruyn, G.A.; Filippucci, E.; Grassi, W.; Iagnocco, A.; Jousse-Joulin, S.; et al. Scoring ultrasound synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: A EULAR-OMERACT ultrasound taskforce-Part 1: Definition and development of a standardised, consensus-based scoring system. RMD Open 2017, 3, e000428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, K.; Akyildiz Tezcan, E.; Akgöl, S. Exploring hand function in newly diagnosed primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Clinical, radiographic, and ultrasonographic insights. J. Hand Ther. 2025, 38, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, S.; Vyas, S.; Bhalla, A.S.; Kumar, U.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, A.K. Ultrasonography in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis of Hand and Wrist Joints: Comparison with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Indian J. Orthop. 2020, 54, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, L.K.N.; Leon, E.P.; Bocate, T.S.; Bonfigliolli, K.R.; Lourenço, S.V.; Bonfa, E.; Pasoto, S.G. Characterizing hand and wrist ultrasound pattern in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A case-control study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutry, N.; Hachulla, E.; Flipo, R.M.; Cortet, B.; Cotten, A. MR imaging findings in hands in early rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison with those in systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjögren syndrome. Radiology 2005, 236, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.E.; Frits, M.L.; Iannaccone, C.K.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Shadick, N.A.; Liao, K.P. Clinical characteristics of RA patients with secondary SS and association with joint damage. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, I.; Nagai, S.; Kitaichi, M.; Nicholson, A.G.; Johkoh, T.; Noma, S.; Kim, D.S.; Handa, T.; Izumi, T.; Mishima, M. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: A clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drimus, J.C.; Duma, R.C.; Trăilă, D.; Mogoșan, C.D.; Manolescu, D.L.; Fira-Mladinescu, O. High-Resolution CT Findings in Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Connective Tissue Diseases: Differentiating Patterns for Clinical Practice-A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.H.; Pan, L.; Gao, Y.B.; Cui, G.H.; Wang, Y.H. Utility of lung ultrasound to identify interstitial lung disease: An observational study based on the STROBE guidelines. Medicine 2021, 100, e25217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rocca, G.; Ferro, F.; Sambataro, G.; Elefante, E.; Fonzetti, S.; Fulvio, G.; Navarro, I.C.; Mosca, M.; Baldini, C. Primary-Sjögren’s-Syndrome-Related Interstitial Lung Disease: A Clinical Review Discussing Current Controversies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalayli, N.; Bouri, M.F.; Wahbeh, M.; Drie, T.; Kudsi, M. Neurological injury in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 3381–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Módis, L.V.; Aradi, Z.; Horváth, I.F.; Bencze, J.; Papp, T.; Emri, M.; Berényi, E.; Bugán, A.; Szántó, A. Central Nervous System Involvement in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Narrative Review of MRI Findings. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzarouchi, L.C.; Tsifetaki, N.; Konitsiotis, S.; Zikou, A.; Astrakas, L.; Drosos, A.; Argyropoulou, M.I. CNS involvement in primary Sjogren Syndrome: Assessment of gray and white matter changes with MRI and voxel-based morphometry. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harboe, E.; Beyer, M.K.; Greve, O.J.; Gøransson, L.G.; Tjensvoll, A.B.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Omdal, R. Cerebral white matter hyperintensities are not increased in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009, 16, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, D.G.; da Hygino da Cruz, L.C., Jr.; Dos Santos, R.Q.; Marcondes, J.; de Abreu, M.M. Brain tumefactive vasculitis in primary Sjögren syndrome. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 27, e15304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassi, S.B.; Nabli, F.; Boubaker, A.; Ghorbel, I.B.; Neji, S.; Hentati, F. Pseudotumoral brain lesion as the presenting feature of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 339, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, L.; Toulgoat, F.; Desal, H.; Laplaud, D.A.; Magot, A.; Hamidou, M.; Wiertlewski, S. Atypical neurologic complications in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Report of 4 cases. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 40, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanahuja, J.; Ordoñez-Palau, S.; Begué, R.; Brieva, L.; Boquet, D. Primary Sjögren Syndrome with tumefactive central nervous system involvement. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 1878–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zou, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cao, B. A case report of Sjögren syndrome manifesting bilateral basal ganglia lesions. Medicine 2017, 96, e6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, I.E.; Chatzis, L.G.; Pezoulas, V.C.; Baldini, C.; Fotiadis, D.I.; Voulgarelis, M.; Tzioufas, A.G.; Goules, A.V. The clinical phenotype of primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients with lymphadenopathy. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolfi, S.; Della-Torre, E.; Bongiovanni, L.; Mehta, P.; Fajgenbaum, D.C.; Selmi, C. Lymphadenopathy in the rheumatology practice: A pragmatic approach. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seror, R.; Bowman, S.J.; Brito-Zeron, P.; Theander, E.; Bootsma, H.; Tzioufas, A.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; Ramos-Casals, M.; Dörner, T.; Ravaud, P.; et al. EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI): A user guide. RMD Open 2015, 1, e000022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissink, A.; van Ginkel, M.S.; Bootsma, H.; Glaudemans, A.; Delli, K. At the cutting-edge: What’s the latest in imaging to diagnose Sjögren’s disease? Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, W.U.; Park, S.H.; Kwok, S.K. Clinical value of salivary gland ultrasonography in evaluating secretory function, disease activity, and lymphoma risk factors in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzon, M.; Spina, E.; Tulipano Di Franco, F.; Giovannini, I.; De Vita, S.; Zabotti, A. Salivary Gland Ultrasound in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Current and Future Perspectives. Open Access Rheumatol. 2022, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Kanematsu, M.; Goto, H.; Mizuta, K.; Aoki, M.; Kuze, B.; Hirose, Y. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the salivary glands: MR imaging findings including diffusion-weighted imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 2012, 81, e612–e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Hua, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, Q.; Tao, X.; Zheng, J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR in the diagnosis of lympho-associated benign and malignant lesions in the parotid gland. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2016, 45, 20150343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, D.D.; Lenghel, L.M.; Ștefan, P.A.; Fodor, D.; Bădărînză, M.; Csutak, C.; Dudea, S.M.; Rusu, G.M. Radiomic Features Associated with Lymphoma Development in the Parotid Glands of Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Cancers 2023, 15, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Iojiban, M.; Stanciu, B.-I.; Damian, L.; Lenghel, L.M.; Solomon, C.; Lupșor-Platon, M. The Role of Imaging Techniques in the Evaluation of Extraglandular Manifestations in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020358

Iojiban M, Stanciu B-I, Damian L, Lenghel LM, Solomon C, Lupșor-Platon M. The Role of Imaging Techniques in the Evaluation of Extraglandular Manifestations in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020358

Chicago/Turabian StyleIojiban, Marcela, Bogdan-Ioan Stanciu, Laura Damian, Lavinia Manuela Lenghel, Carolina Solomon, and Monica Lupșor-Platon. 2026. "The Role of Imaging Techniques in the Evaluation of Extraglandular Manifestations in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020358

APA StyleIojiban, M., Stanciu, B.-I., Damian, L., Lenghel, L. M., Solomon, C., & Lupșor-Platon, M. (2026). The Role of Imaging Techniques in the Evaluation of Extraglandular Manifestations in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Diagnostics, 16(2), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020358