DL-PCMNet: Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network for Skin Cancer Classification with Dermatoscopic Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges

- ➢

- The method VGG-SVM in [1] faced high computational complexity issues, and it restricts its applicability to clinical applications;

- ➢

- The model suggested in [3] had class imbalance issues in the dataset because it needed a vast amount of medical image data for effective training;

- ➢

- The model encountered in [4] is computationally expensive, and evaluating the model can utilize additional resources;

- ➢

- ➢

- The model suggested in [8] achieves better performance, but it limits its interpretability in clinical applications due to a lack of transparency.

2.2. Problem Statement

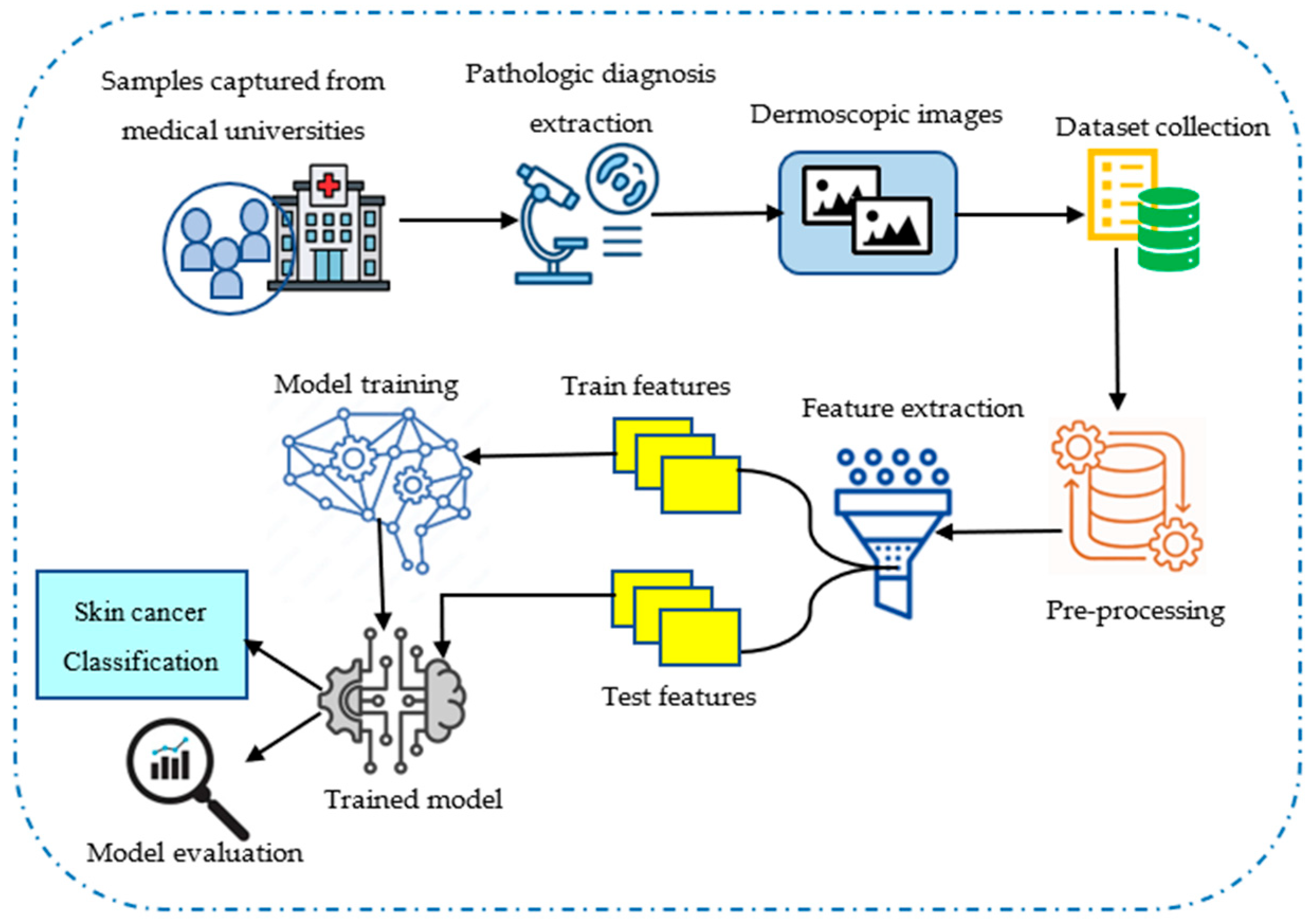

3. System Model

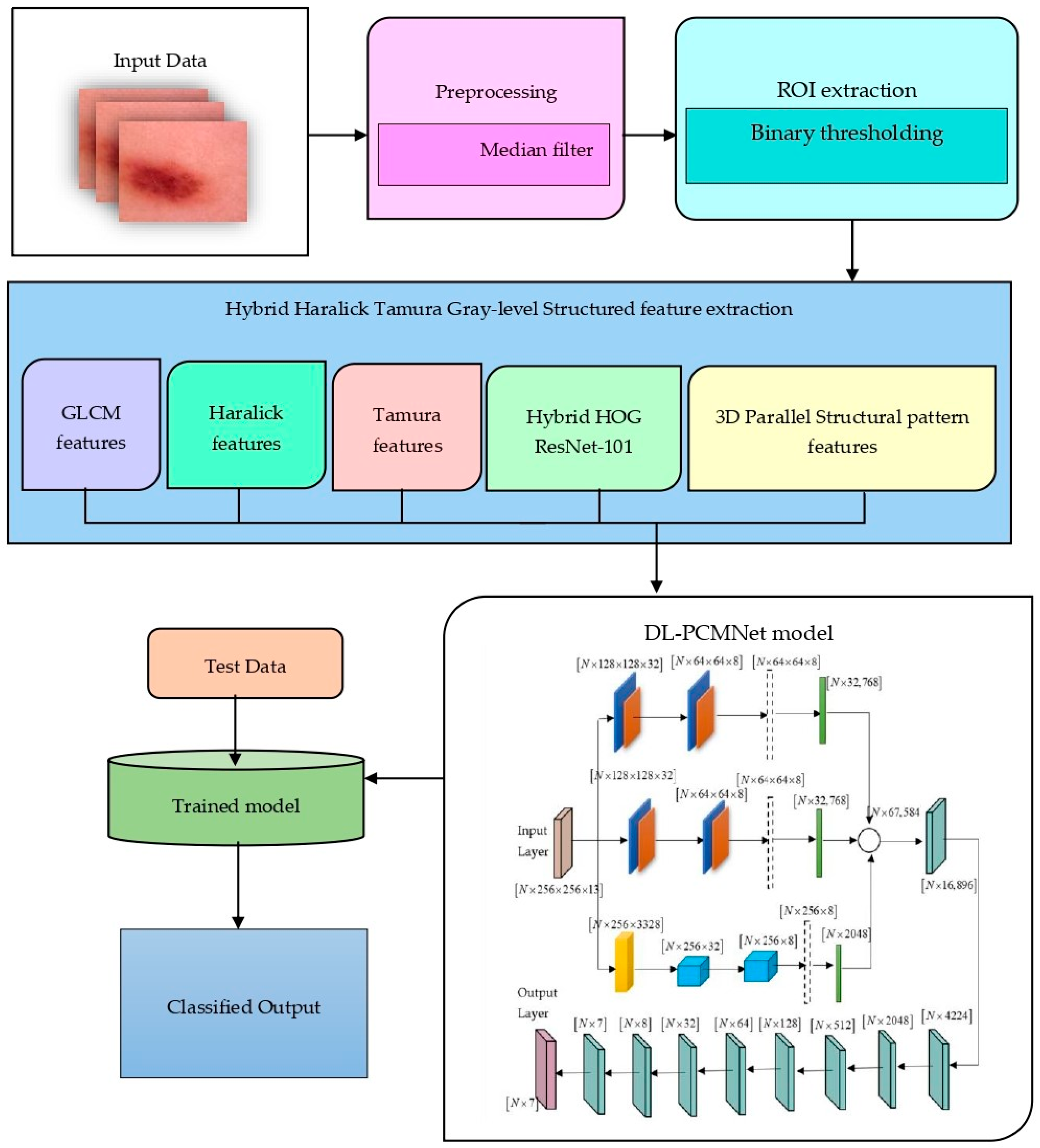

4. Skin Cancer Classification Using Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network

4.1. Collection of Input Data

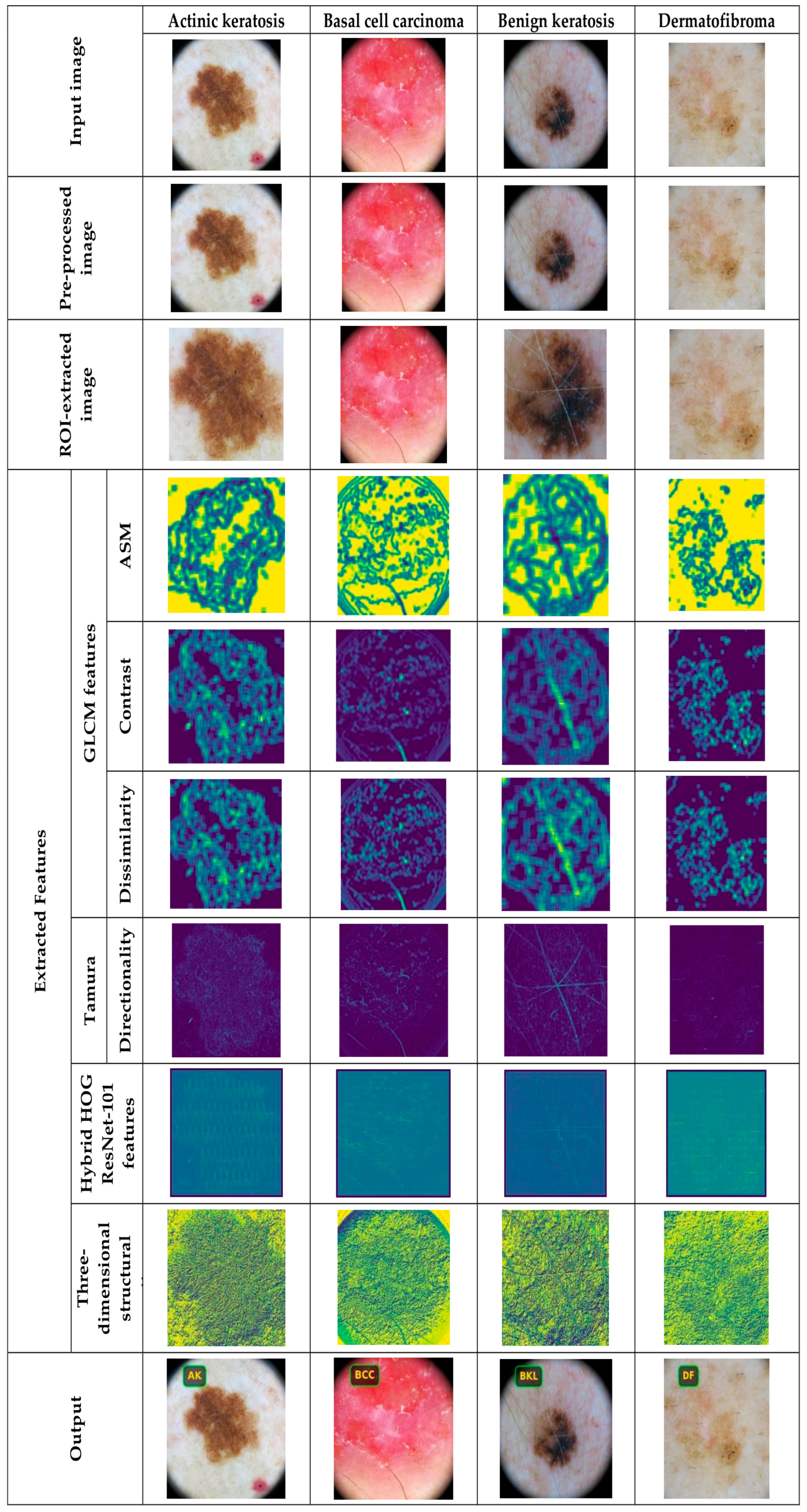

4.2. Data Pre-Processing and ROI Extraction

4.3. Feature Extraction Using Hybrid Haralick Tamura Gray-Level Structured Features (H2TGS)

4.3.1. Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix Feature

4.3.2. Haralick Features

4.3.3. Tamura Feature

4.3.4. Hybrid HOG ResNet-101 Features

4.3.5. Three-Dimensional Parallel Structural Pattern Features

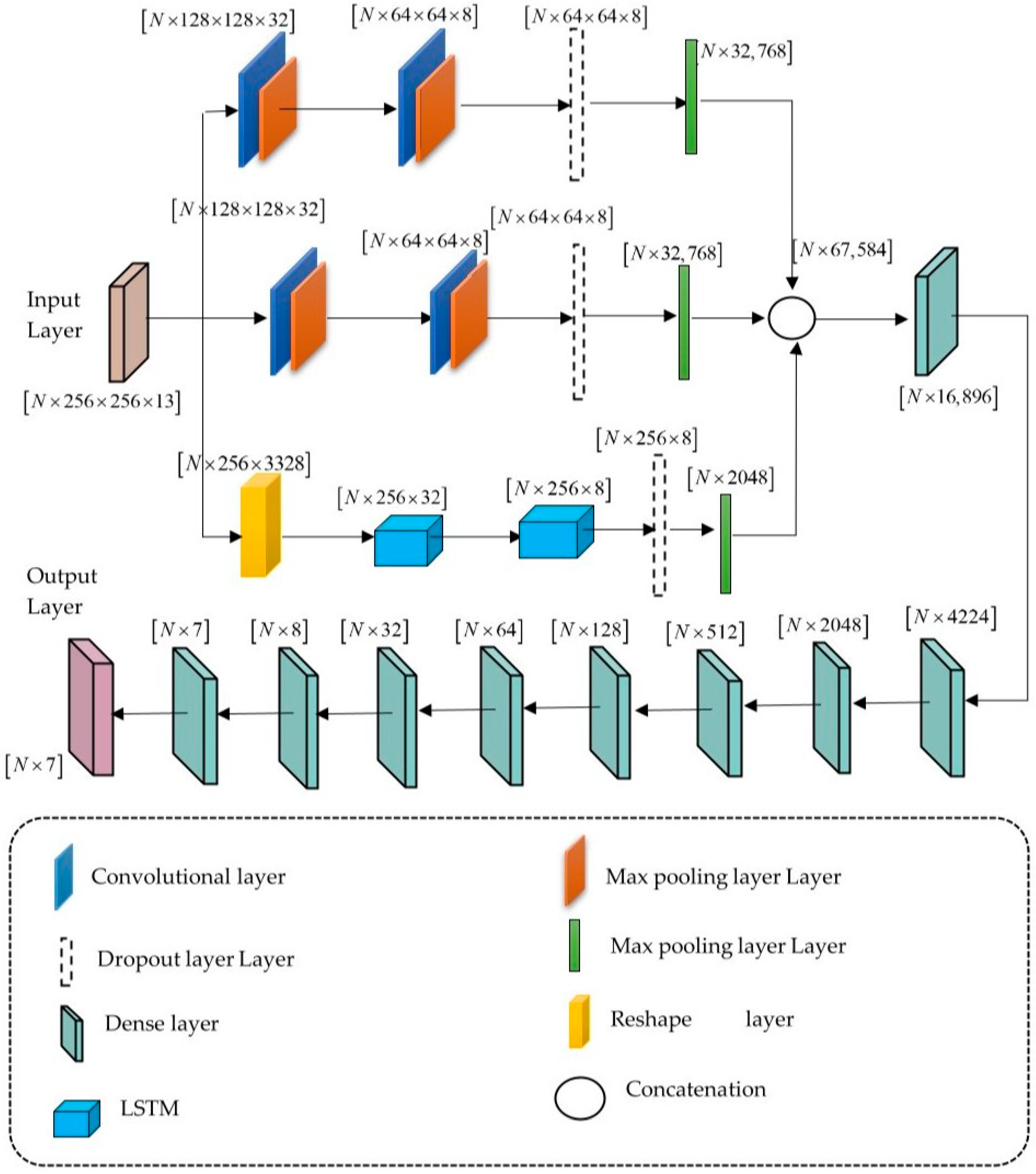

4.4. Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network Model

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Dataset Description

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

5.4. Experimental Results

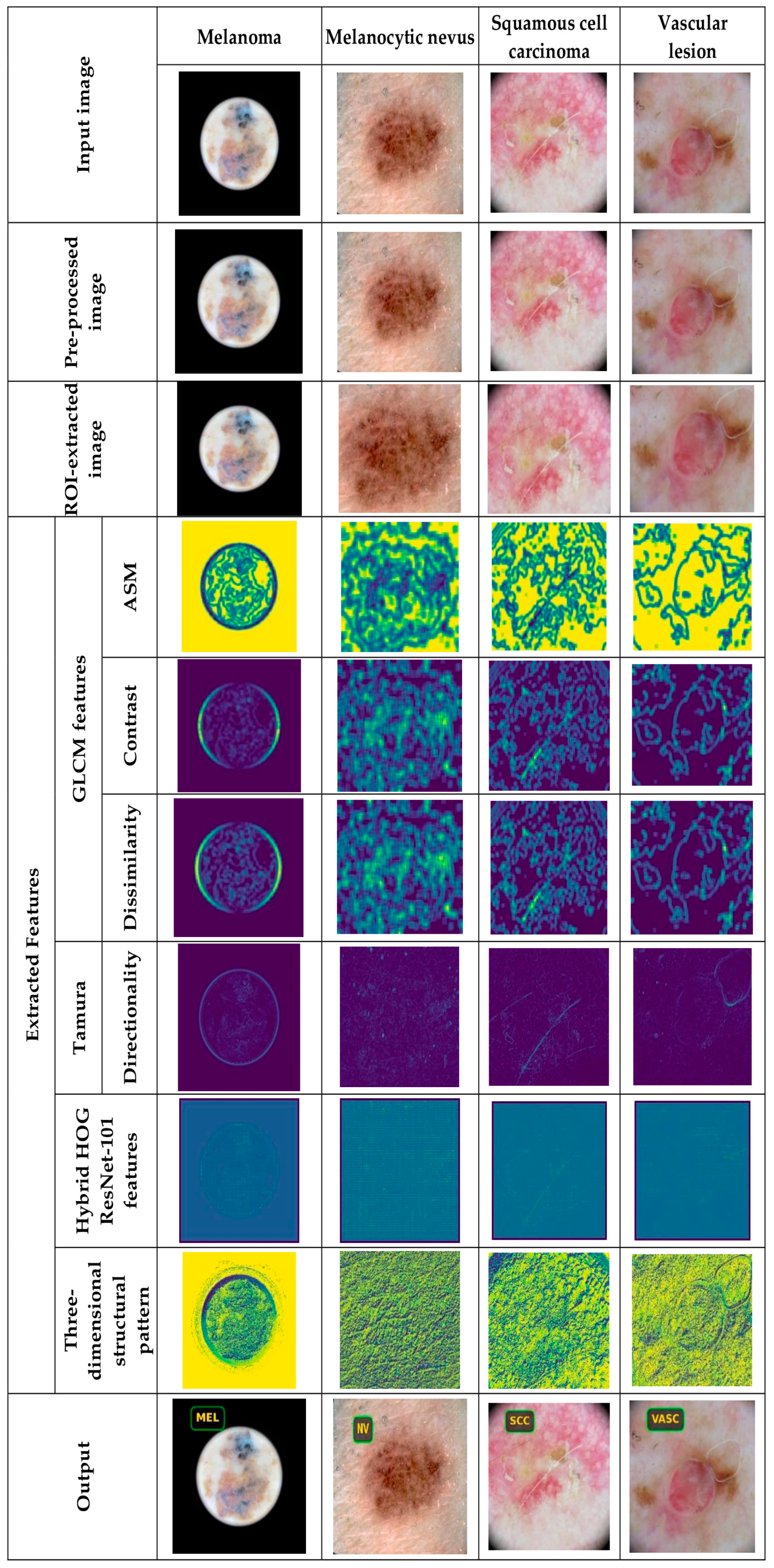

5.4.1. Image Results Using ISIC 2019 Skin Lesion Dataset

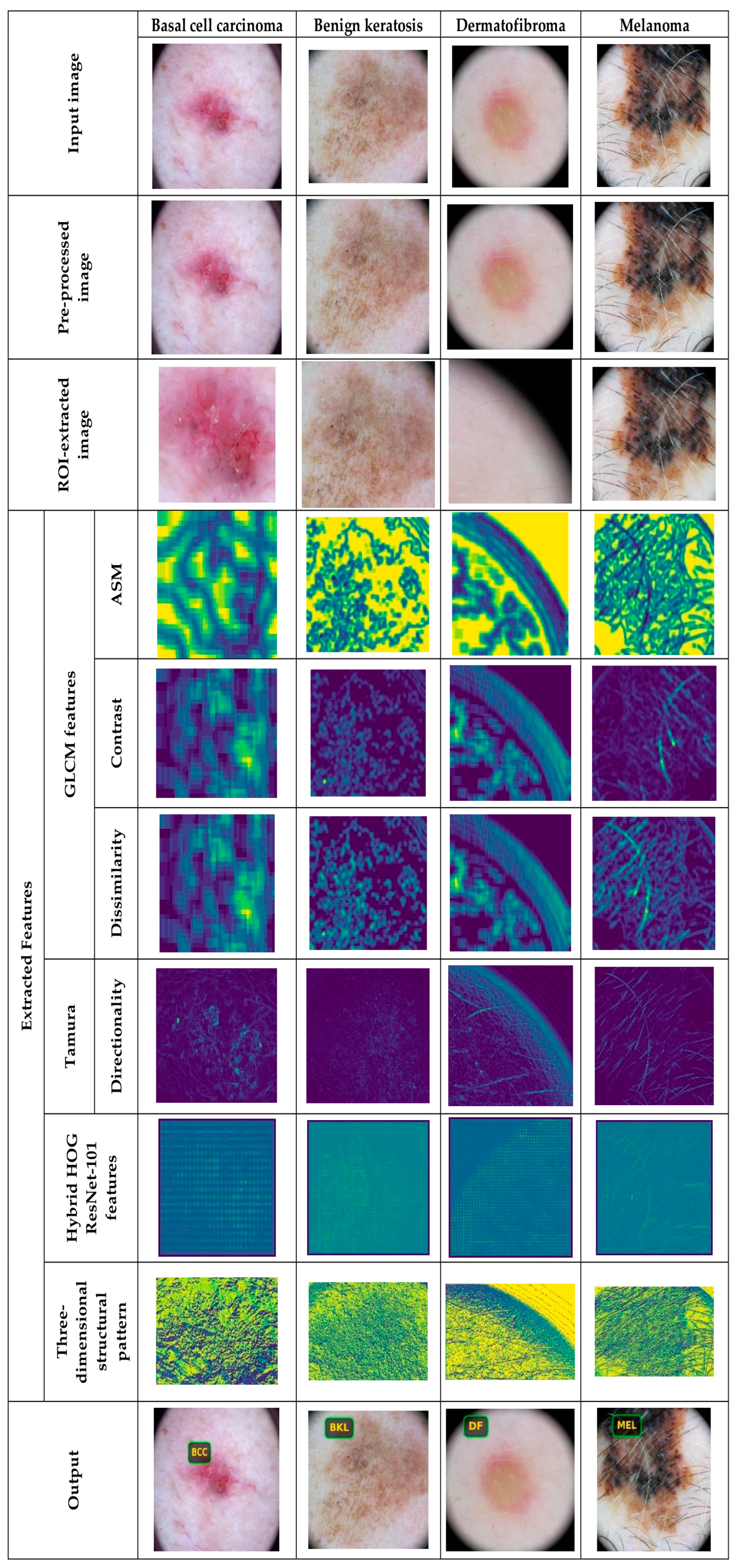

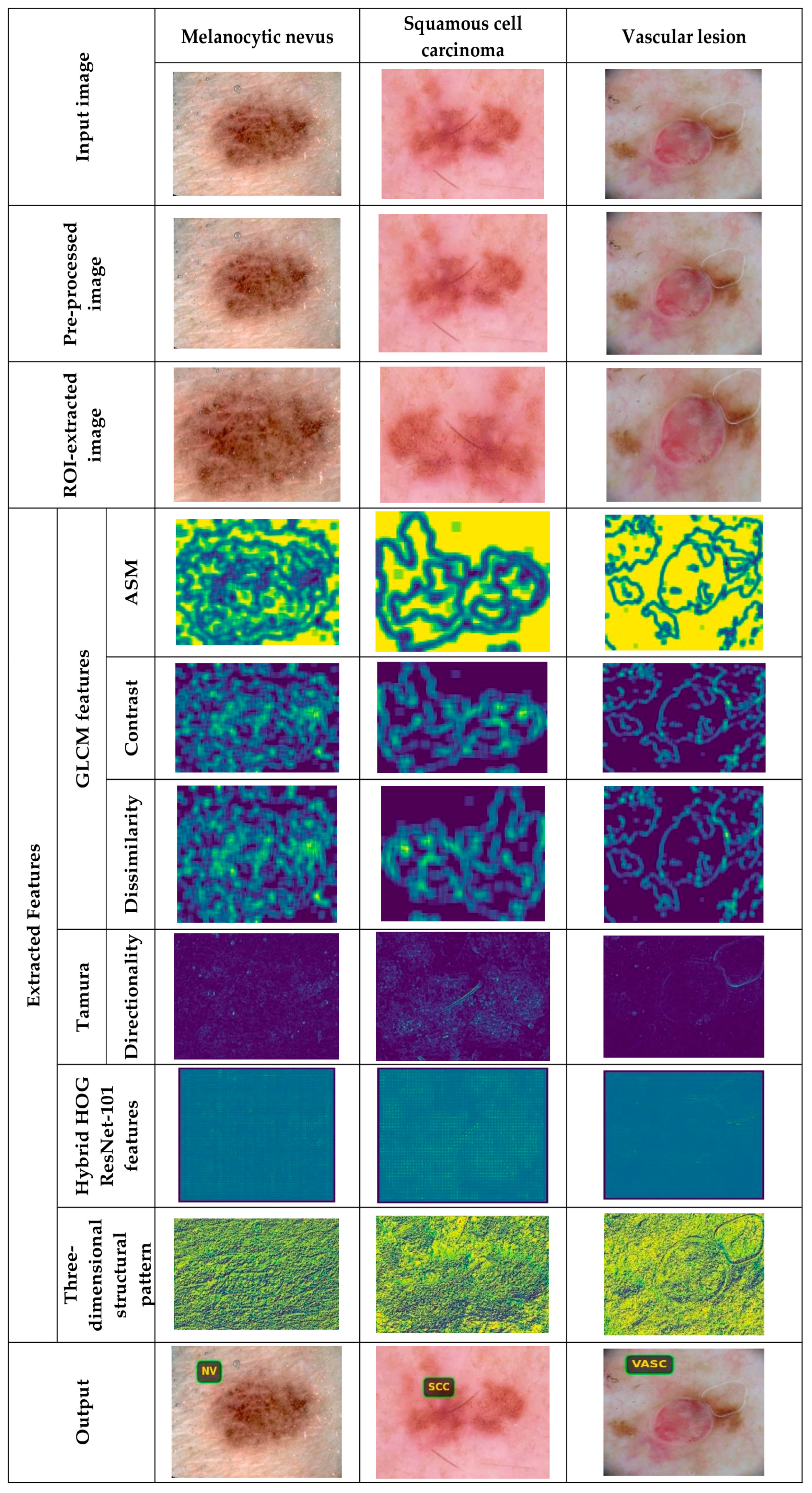

5.4.2. Image Results Using theSkin Cancer MNIST: HAM10000 Dataset

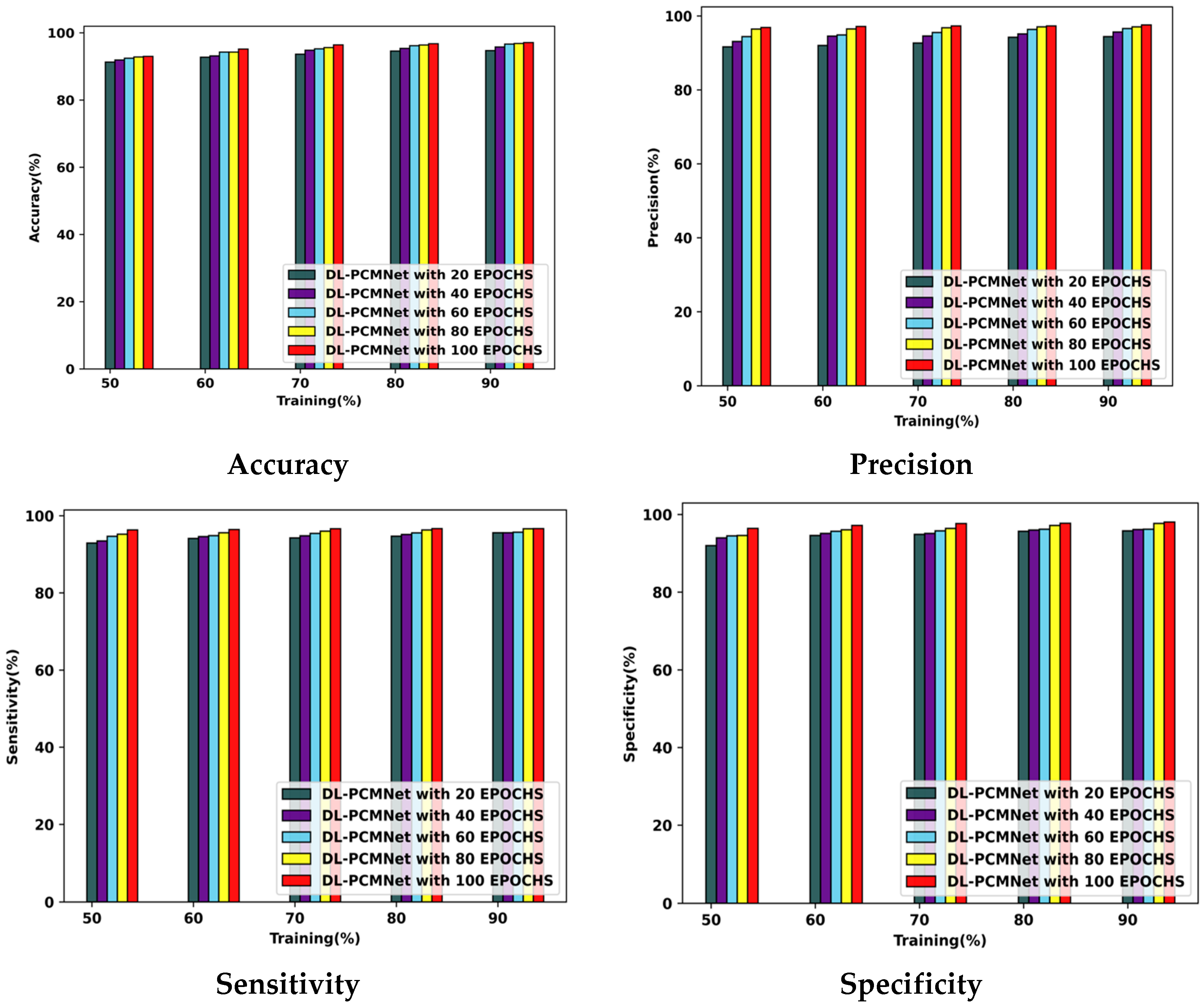

5.5. Performance Analysis

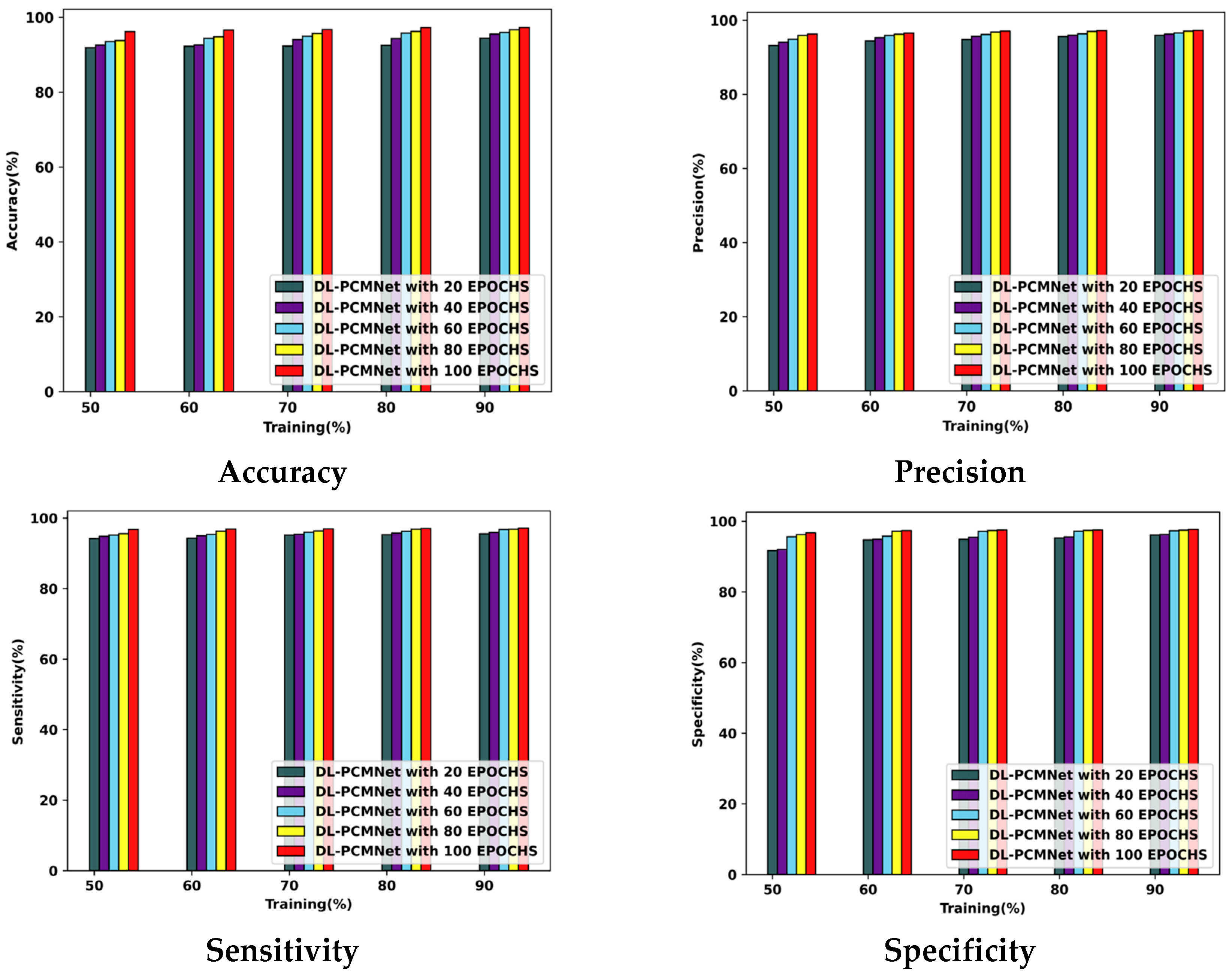

5.5.1. Performance Analysis Using the ISIC 2019 Skin Lesion Dataset

5.5.2. Performance Analysis Using Skin Cancer MNIST: HAM10000 Dataset

5.6. Comparative Methods

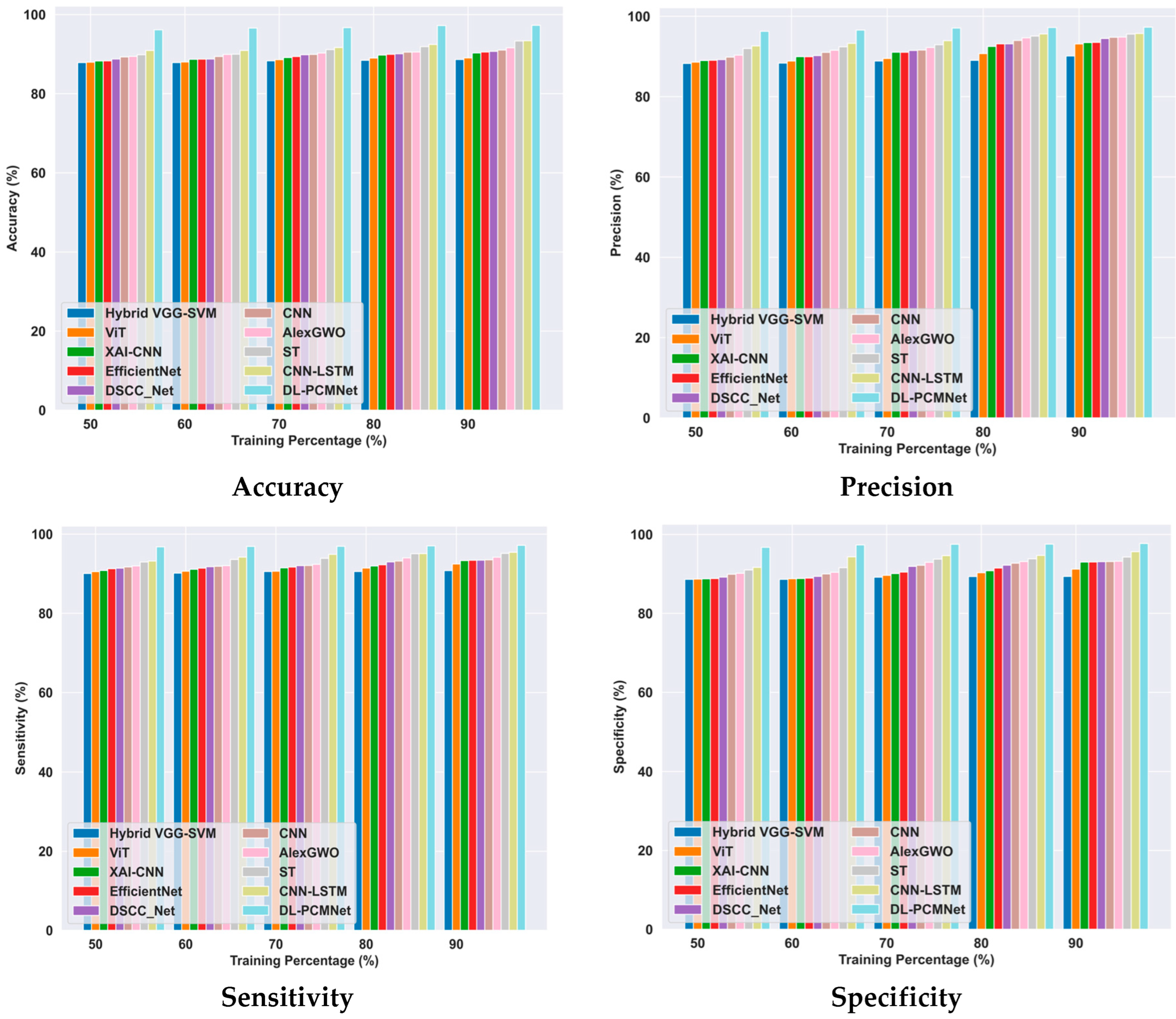

5.6.1. Comparative Analysis Using the ISIC 2019 Skin Lesion Dataset

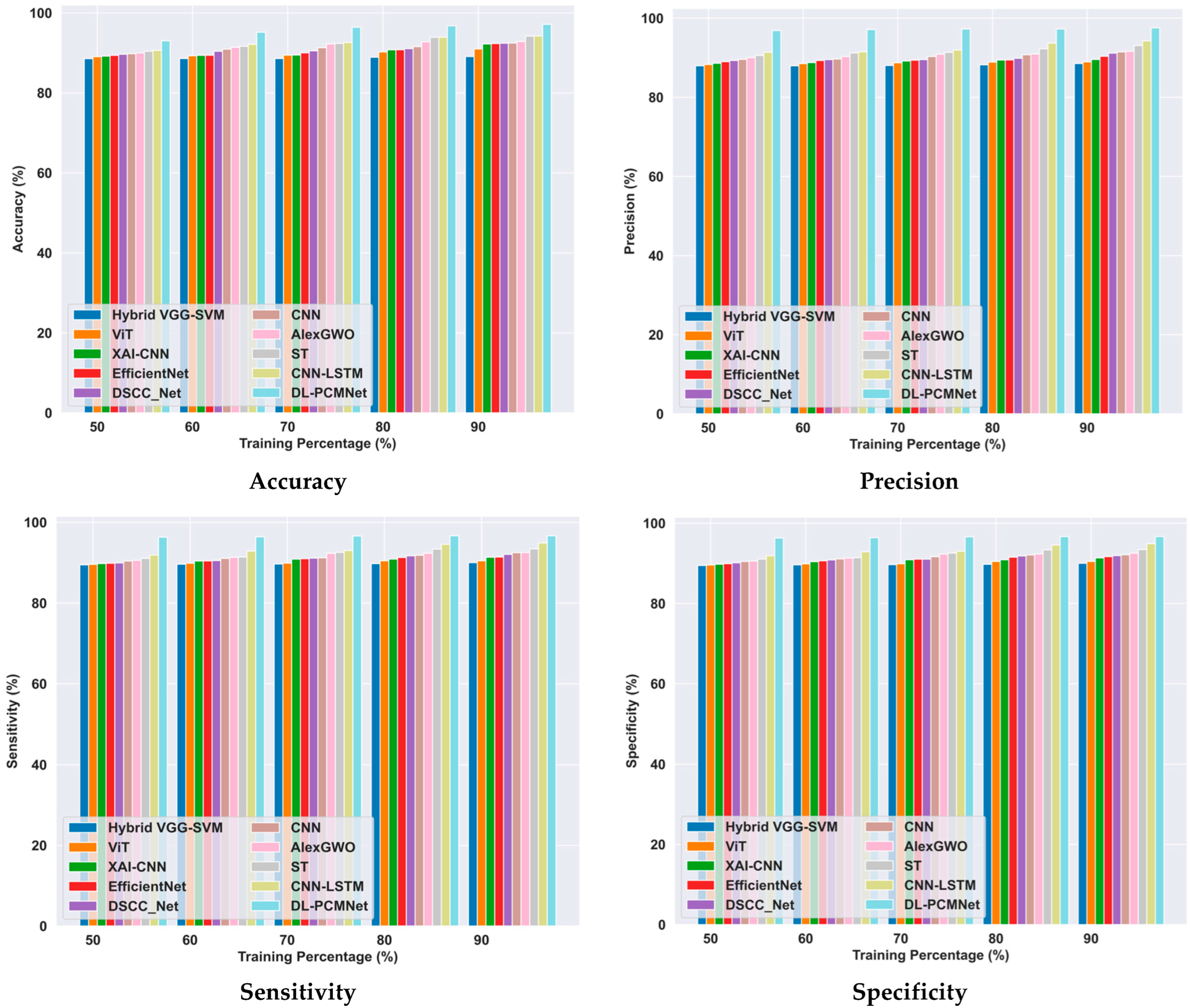

5.6.2. Comparative Analysis Using the Skin Cancer MNIST: HAM10000 Dataset

5.7. Comparative Discussion

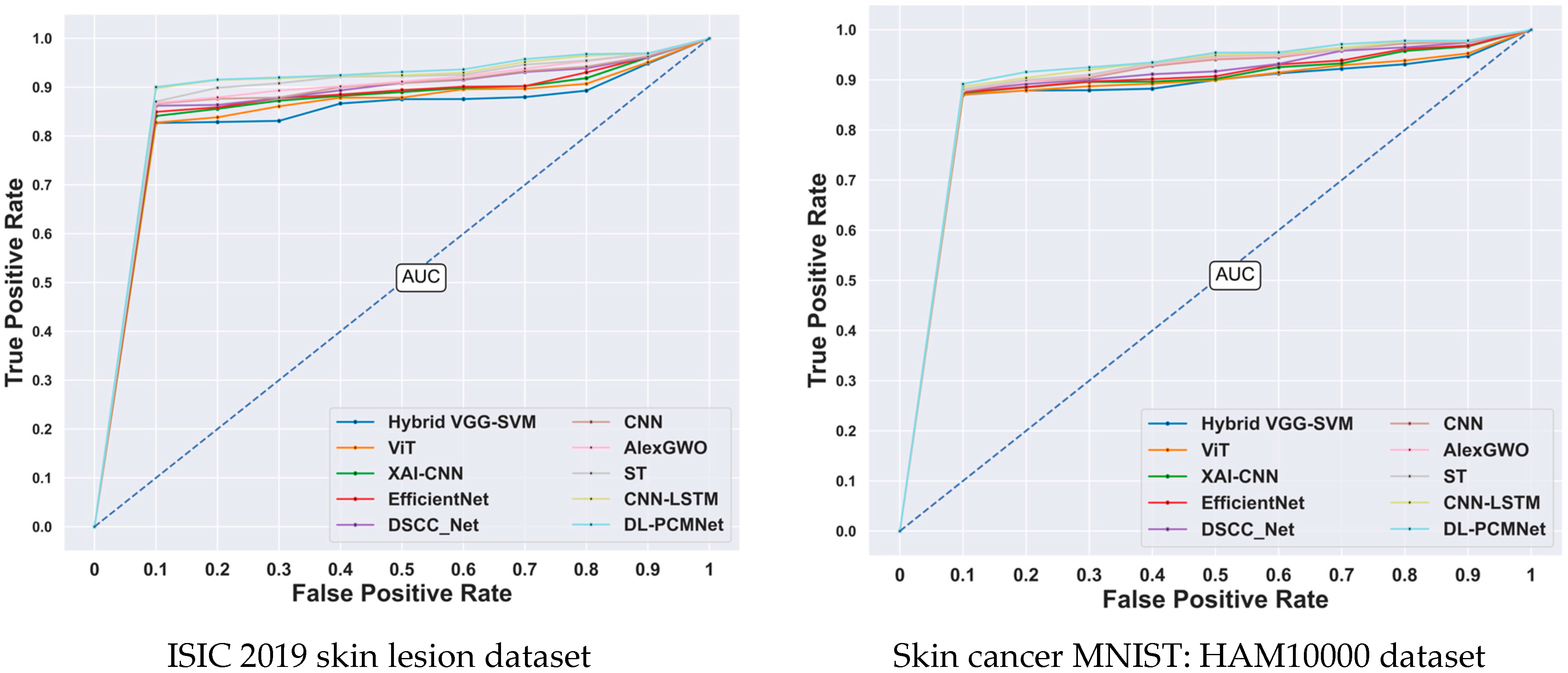

5.8. ROC Analysis

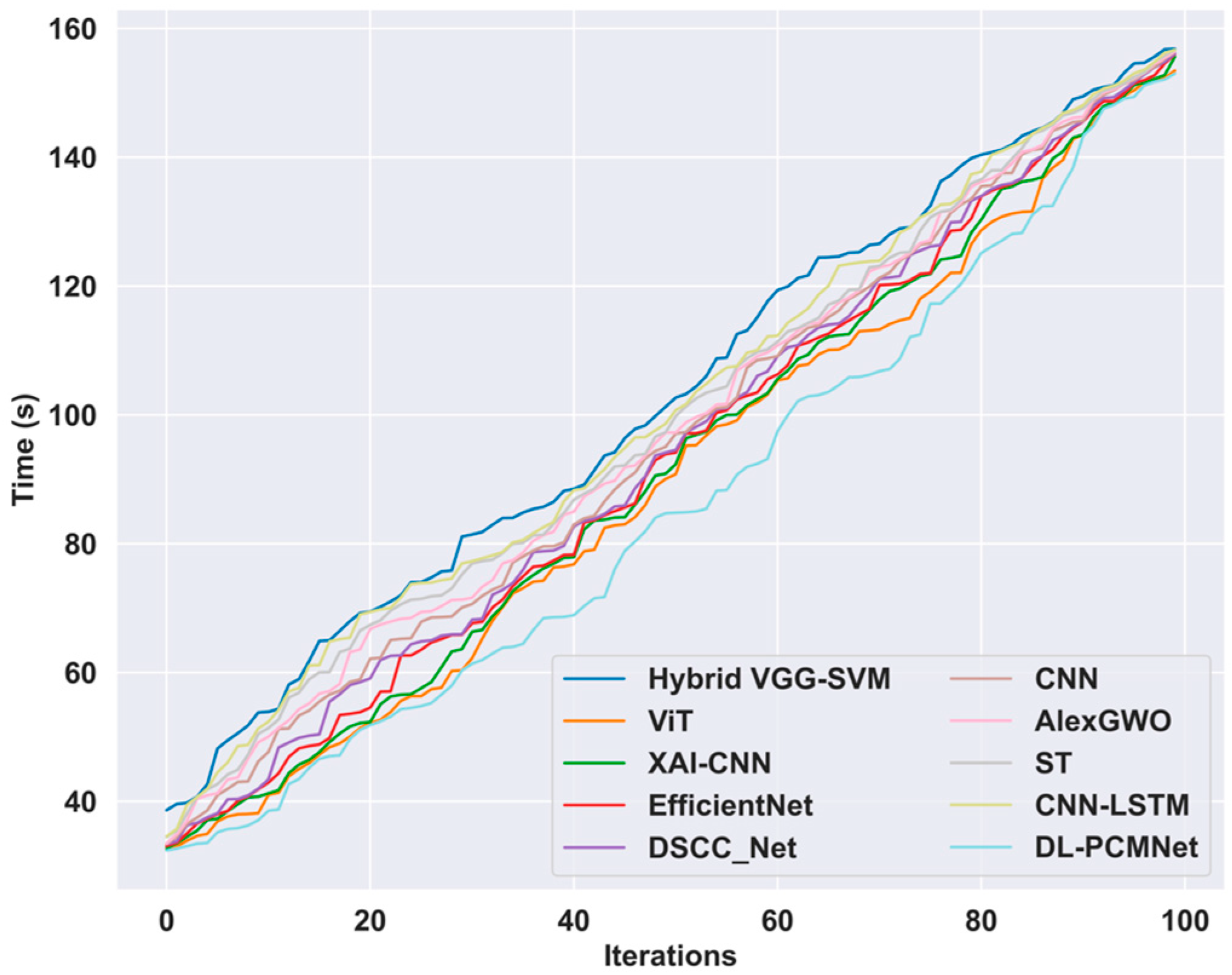

5.9. Time Complexity Analysis

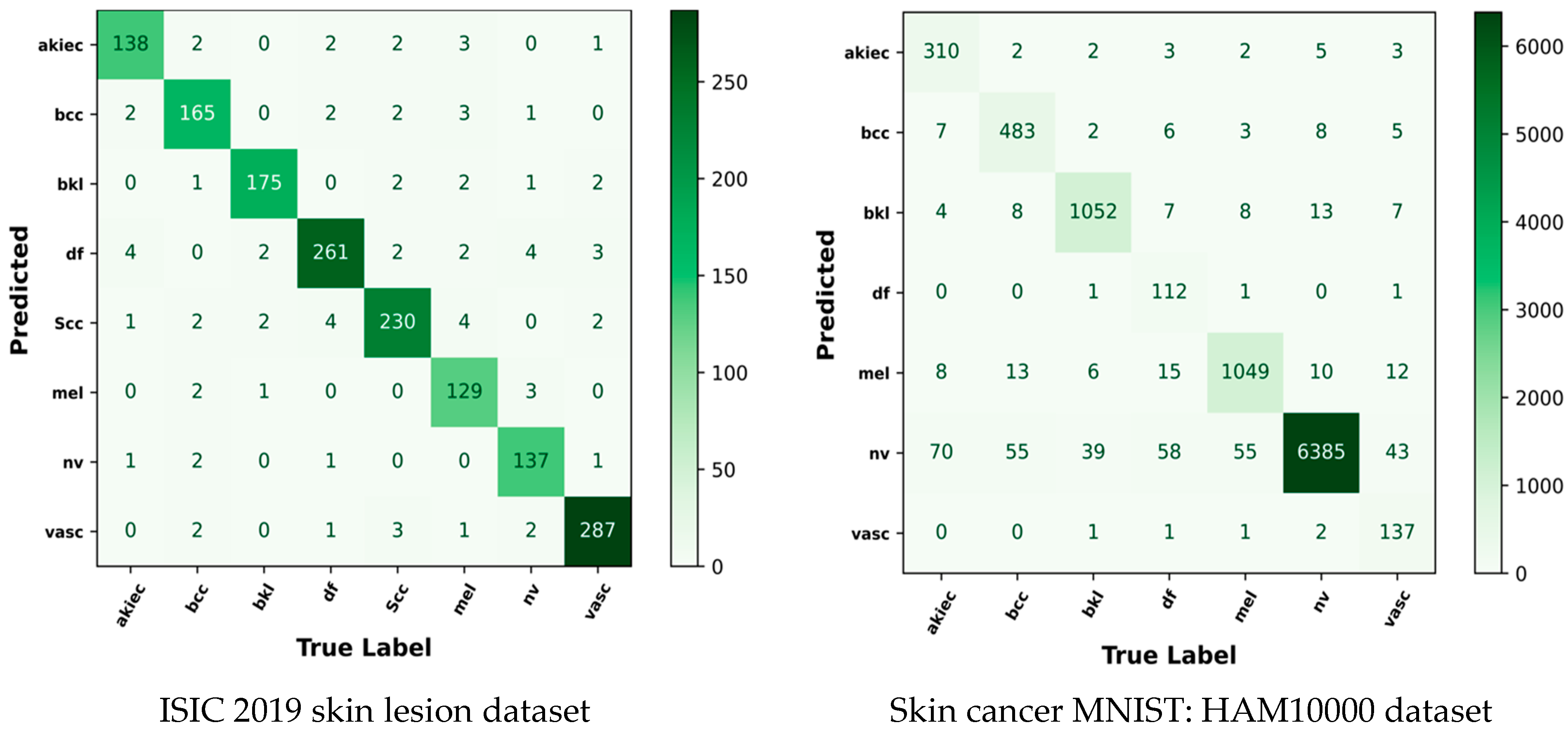

5.10. Confusion Matrix

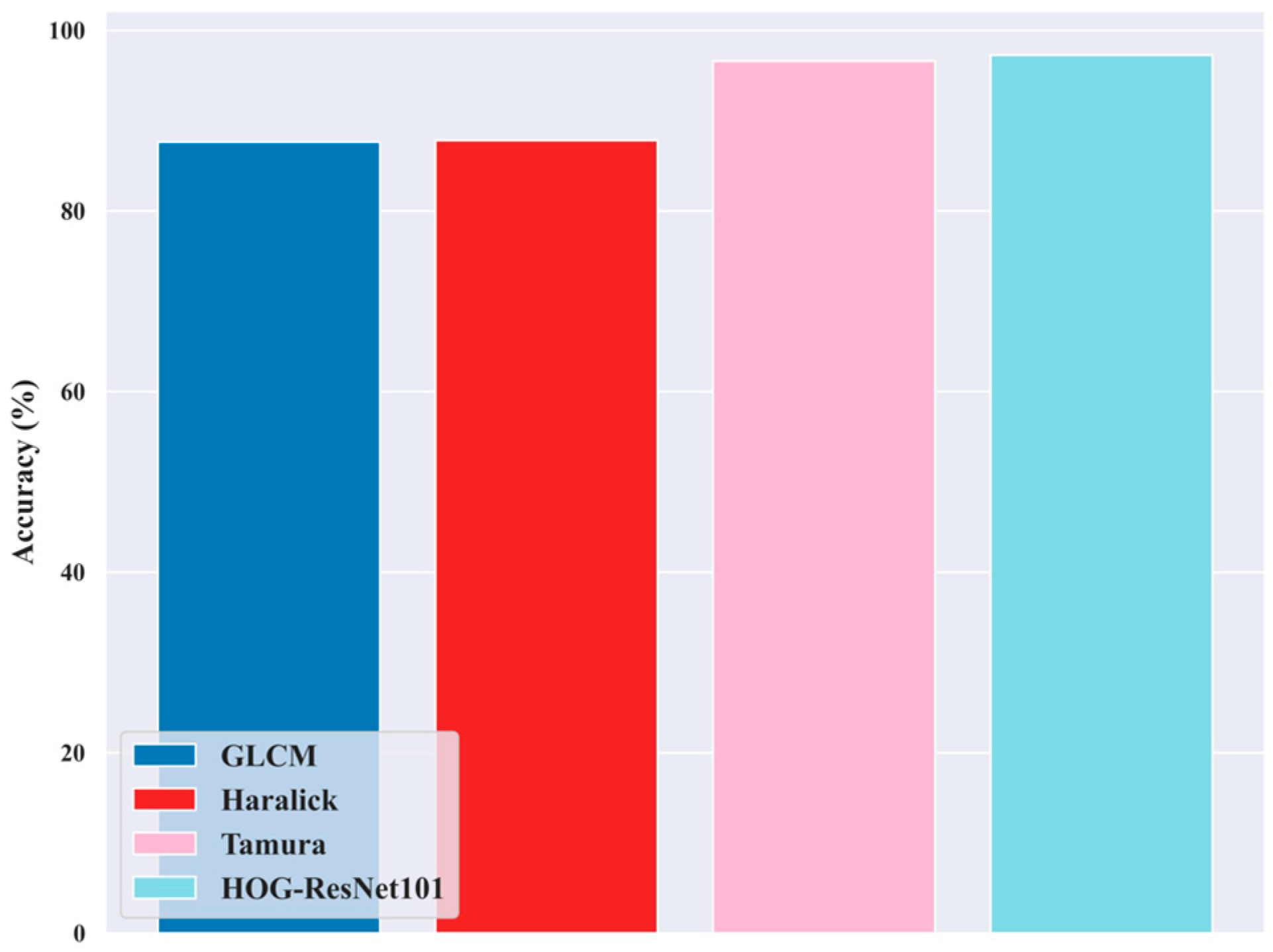

5.11. Ablation Study for Feature Extraction Techniques

5.12. Statistical T-Test Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeed, M.; Naseer, A.; Masood, H.; Rehman, S.U.; Gruhn, V. The power of generative ai to augment for enhanced skin cancer classification: A deep learning approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 130330–130344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshed, M.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Ahmed, S.; Tahir, M.; Shafi, M. Multi-class skin cancer classification using vision transformer networks and convolutional neural network-based pre-trained models. Information 2023, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, D.; Venugopal, V.; Nath, M.K.; Mishra, M. Hybrid convolutional neural networks with SVM classifier for classification of skin cancer. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2023, 5, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururaj, H.L.; Manju, N.; Nagarjun, A.; Aradhya, V.N.M.; Flammini, F. DeepSkin: A deep learning approach for skin cancer classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 50205–50214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridha, K.; Uddin, M.; Shin, J.; Khadka, S.; Mridha, M.F. An interpretable skin cancer classification using optimized convolutional neural network for a smart healthcare system. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41003–41018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, A.; Hussein, H.; Abdel-Kader, R.F.; El Salam, K.A. Performance enhancement of skin cancer classification using computer vision. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 72120–72133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallazzi, M.; Biavaschi, S.; Bulgheroni, A.; Gatti, T.M.; Corchs, S.; Gallo, I. A large dataset to enhance skin cancer classification with transformer-based deep neural networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109544–109559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, M.; Elgendy, I.A.; Chelloug, S.A.; Albashrawi, M.A. Attention-based Convolutional Neural Network Model for Skin Cancer Classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 172027–172050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Luo, S.; Greer, P. A novel vision transformer model for skin cancer classification. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 55, 9335–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfed, N.; Khelifi, F.; Bouridane, A.; Seker, H. Pigment network-based skin cancer detection. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 7214–7217. [Google Scholar]

- Ünver, H.M.; Ayan, E. Skin lesion segmentation in dermoscopic images with combination of YOLO and grabcut algorithm. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Jung, S.H.; Won, H.H. WonDerM: Skin lesion classification with fine-tuned neural networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Shorfuzzaman, M. An explainable stacked ensemble of deep learning models for improved melanoma skin cancer detection. Multimed. Syst. 2022, 28, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Daescu, O. Deep learning for skin lesion segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Kansas City, MO, USA, 13–16 November 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Panja, A.; Christy, J.J.; Abdul, Q.M. An approach to skin cancer detection using Keras and Tensorflow. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1911, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A. Multiclass skin cancer classification using EfficientNets–a first step towards preventing skin cancer. Neurosci. Inform. 2022, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, B.; Zeng, A.; Pan, D.; Wang, R.; Zhao, S. Skin cancer classification with deep learning: A systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 893972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIC. Skin Lesion Images for Classification. 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/salviohexia/isic-2019-skin-lesion-images-for-classification/data (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Skin Cancer MNIST: HAM10000. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Gayathri, S.; Krishna, A.K.; Gopi, V.P.; Palanisamy, P. Automated binary and multiclass classification of diabetic retinopathy using Haralick and multiresolution features. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57497–57504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M. Texture Feature Extraction Using Tamura Descriptors and Scale-Invariant Feature Transform. J. Educ. Sci. 2023, 32, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakheet, S. An SVM framework for malignant melanoma detection based on optimized HOG features. Computation 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwinda, D.; Bustamam, A. Detection of Alzheimer’s disease using advanced local binary pattern from the hippocampus and whole brain of MR images. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 5051–5056. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, S.; Sagheer, A. Difference-based local gradient patterns for image representation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing, Genoa, Italy, 7–11 September 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaseeli, J.D.D.; Briskilal, J.; Fancy, C.; Vaitheeshwaran, V.; Patibandla, R.S.M.L.; Syed, K.; Swain, A.K. An intelligent framework for skin cancer detection and classification using fusion of Squeeze-Excitation-DenseNet with Metaheuristic-driven ensemble deep learning models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Xia, J.; Du, P.; Lin, C.; Samat, A. Integrating multilayer features of convolutional neural networks for remote sensing scene classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 5653–5665. [Google Scholar]

- Harahap, M.; Husein, A.M.; Kwok, S.C.; Wizley, V.; Leonardi, J.; Ong, D.K.; Ginting, D.; Silitonga, B.A. Skin cancer classification using EfficientNet architecture. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2024, 13, 2716–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Naeem, A.; Malik, H.; Tanveer, J.; Naqvi, R.A.; Lee, S.-W. DSCC_Net: Multi-classification deep learning models for the diagnosis of skin cancer using dermoscopic images. Cancers 2023, 15, 2179. [Google Scholar]

| GLCM Feature | Description | Formula | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homogeneity | To calculate the rigidity of element distribution, homogeneity uses a value. | Where . | |

| Contrast | Contrast measures the difference in color of any object. | ||

| Entropy | The function entropy measures the randomness or complexity of an image. | ||

| Dissimilarity | Dissimilarity measures the dissimilarity of textures present in an image. | ||

| Angular Second Moment | It quantifies the uniformity of an image’s gray-level distribution. |

| Hyperparameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 32 |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Number of epochs | 500 |

| Loss function | Categorical Cross-Entropy |

| Metrics | Accuracy |

| Activation Function | ReLU |

| Default Optimizer | Adam |

| Dropout rate | 0.2 |

| Number of convolutional layers | 4 |

| Number of LSTM layers | 2 |

| Filter size of convolutional layers | 32, 8, 32, 8 |

| Unit of LSTM layers | 32, 8 |

| Padding | Same |

| Pool size | 2 |

| Kernal size | 3 |

| Techniques | Hybrid VGG-SVM | ViT | XAI-CNN | EfficientNet | DSCC_Net | CNN | AlexGWO | ST | CNN-LSTM | DL-PCMNet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISIC 2019 skin lesion dataset | Accuracy (%) | 88.64 | 89.04 | 90.28 | 90.54 | 90.70 | 91.05 | 91.60 | 93.33 | 93.39 | 97.28 |

| Precision (%) | 90.11 | 93.11 | 93.46 | 93.52 | 94.48 | 94.79 | 94.83 | 95.59 | 95.73 | 97.30 | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 90.78 | 92.46 | 93.30 | 93.39 | 93.42 | 93.52 | 94.16 | 95.12 | 95.40 | 97.17 | |

| Specificity (%) | 89.36 | 91.22 | 93.00 | 93.02 | 93.12 | 93.13 | 93.23 | 94.27 | 95.65 | 97.72 | |

| Skin cancer MNIST: HAM10000 dataset | Accuracy (%) | 89.06 | 90.98 | 92.22 | 92.33 | 92.41 | 92.46 | 92.85 | 94.17 | 94.25 | 97.13 |

| Precision (%) | 88.53 | 88.96 | 89.56 | 90.37 | 91.16 | 91.47 | 91.65 | 93.09 | 94.27 | 97.57 | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 90.01 | 90.48 | 91.34 | 91.40 | 92.06 | 92.47 | 92.53 | 93.45 | 94.88 | 96.68 | |

| Specificity (%) | 90.01 | 90.48 | 91.34 | 91.69 | 91.92 | 92.16 | 92.53 | 93.45 | 94.88 | 96.68 | |

| Methods/Metrics | ISIC 2019 Skin Lesion Dataset | Skin Cancer MNIST: HAM10000 Dataset | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||||

| T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | T-Statistic | p-Value | |

| Hybrid VGG-SVM | 2.34 | 0.08 | 1.99 | 0.12 | 2.57 | 0.06 | 2.44 | 0.07 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 2.65 | 0.06 | 2.65 | 0.06 |

| ViT | 2.41 | 0.07 | 1.92 | 0.13 | 1.63 | 0.18 | 2.20 | 0.09 | 2.05 | 0.11 | 3.07 | 0.04 | 2.66 | 0.06 | 2.66 | 0.06 |

| XAI-CNN | 2.67 | 0.06 | 2.70 | 0.05 | 2.09 | 0.10 | 1.97 | 0.12 | 1.77 | 0.15 | 2.74 | 0.05 | 3.31 | 0.03 | 3.31 | 0.03 |

| EfficientNet | 2.70 | 0.05 | 2.61 | 0.06 | 1.89 | 0.13 | 2.17 | 0.10 | 1.82 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 0.09 | 3.24 | 0.03 | 3.28 | 0.03 |

| DSCC_Net | 2.29 | 0.08 | 2.62 | 0.06 | 2.44 | 0.07 | 2.50 | 0.07 | 2.51 | 0.07 | 1.70 | 0.16 | 2.96 | 0.04 | 3.08 | 0.04 |

| CNN | 2.25 | 0.09 | 2.60 | 0.06 | 2.08 | 0.11 | 2.45 | 0.07 | 3.24 | 0.03 | 2.19 | 0.09 | 2.80 | 0.05 | 3.25 | 0.03 |

| AlexGWO | 2.55 | 0.06 | 2.73 | 0.05 | 1.96 | 0.12 | 2.62 | 0.06 | 3.49 | 0.03 | 2.59 | 0.06 | 3.32 | 0.03 | 3.32 | 0.03 |

| ST | 2.17 | 0.10 | 2.20 | 0.09 | 2.77 | 0.05 | 2.83 | 0.05 | 2.97 | 0.04 | 2.56 | 0.06 | 2.65 | 0.06 | 2.65 | 0.06 |

| CNN-LSTM | 2.01 | 0.12 | 2.59 | 0.06 | 3.44 | 0.03 | 3.78 | 0.02 | 3.18 | 0.03 | 1.97 | 0.12 | 2.79 | 0.05 | 2.79 | 0.05 |

| DL-PCMNet | 3.06 | 0.04 | 3.10 | 0.04 | 2.70 | 0.05 | 3.76 | 0.02 | 3.59 | 0.02 | 3.08 | 0.04 | 2.93 | 0.04 | 2.93 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alhassan, A.M.; Altmami, N.I. DL-PCMNet: Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network for Skin Cancer Classification with Dermatoscopic Images. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020359

Alhassan AM, Altmami NI. DL-PCMNet: Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network for Skin Cancer Classification with Dermatoscopic Images. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020359

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhassan, Afnan M., and Nouf I. Altmami. 2026. "DL-PCMNet: Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network for Skin Cancer Classification with Dermatoscopic Images" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020359

APA StyleAlhassan, A. M., & Altmami, N. I. (2026). DL-PCMNet: Distributed Learning Enabled Parallel Convolutional Memory Network for Skin Cancer Classification with Dermatoscopic Images. Diagnostics, 16(2), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020359