The Role of Aurora Kinase A in HBV-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinomas: A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Creation of Study Protocol and Selection of Cases

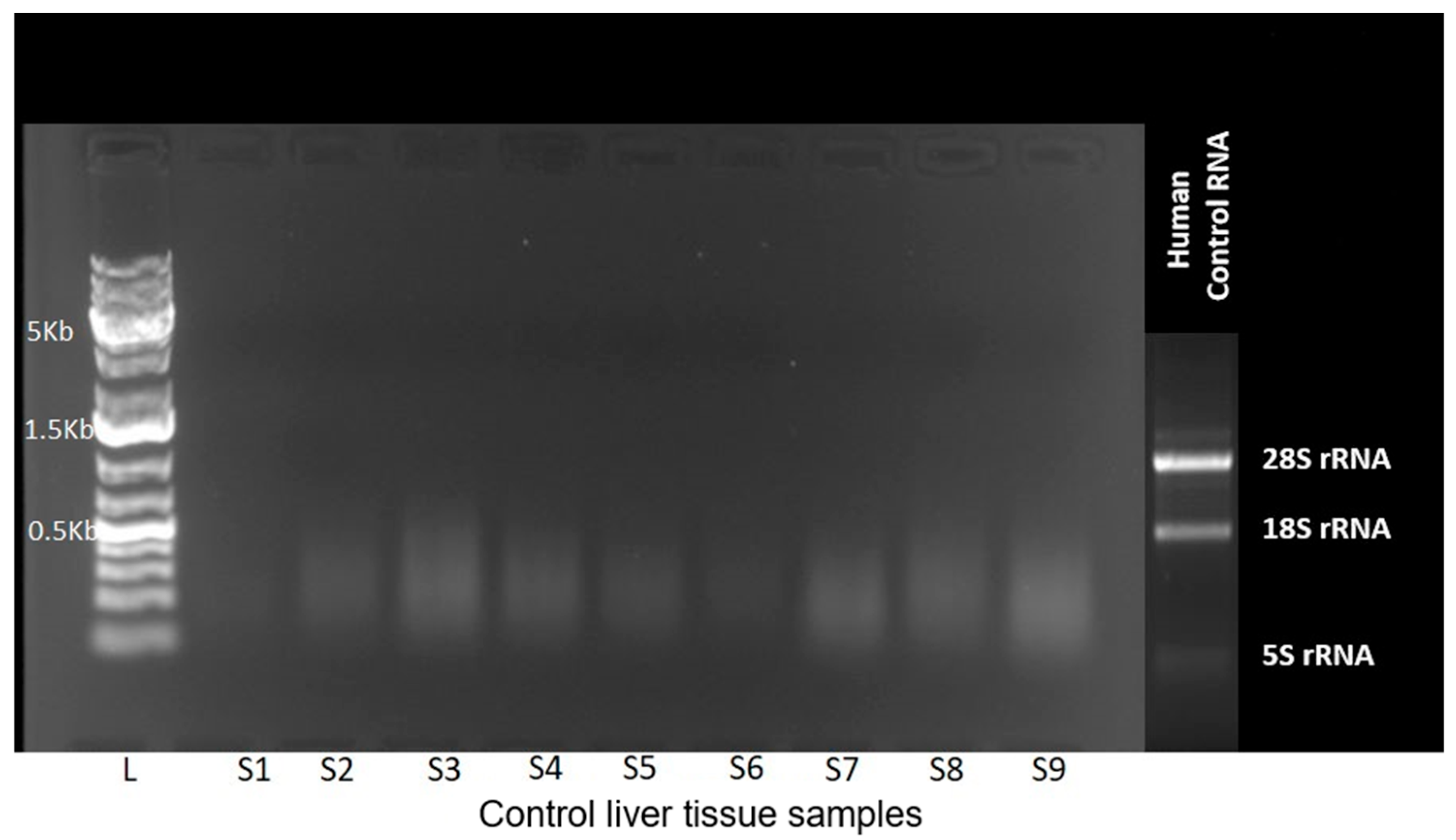

2.2. Molecular Genetic Analyzes

2.3. Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AURKA Gene Expression

3.2. AURKA Gene Copy Number Variation

3.3. Immunohistochemical Markers Findings

4. Discussion

Factors Limiting the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.G.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S.; Lencioni, R.; Koike, K.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Finn, R.S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, K.A.; Petrick, J.L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2021, 73, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, D.; Mishra, A.; Rai, S.N.; Vamanu, E.; Singh, M.P. Identification of Prognostic Biomarkers for Suppressing Tumorigenesis and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Transcriptome Analysis. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, K.S.; Lagarón, N.O.; McGowan, E.M.; Parmar, I.; Jha, A.; Hubbard, B.P.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: Progress, challenges and future directions. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R. A historical overview of protein kinases and their targeted small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.; Ricci, A.D. Challenges and Future Trends of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahnassy, A.A.; Zekri, A.-R.N.; Loutfy, S.A.; Mohamed, W.S.; Moneim, A.A.; Salem, S.E.; Sheta, M.M.; Omar, A.; Al-Zawahry, H. The role of cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases in development and progression of hepatitis C virus-genotype 4-associated hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2011, 91, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghufran, H.; Azam, M.; Mehmood, A.; Butt, H.; Riazuddin, S. Standardization of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma rat model with time based molecular assessment. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2021, 123, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, O.; Sahin, T.K.; Karahan, L.; Rizzo, A.; Guven, D.C. Prognostic significance of the cachexia index (CXI) in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 68, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, D.C.; Lee, J.E.; Yoo, J.E.; Oh, B.-K.; Choi, G.H.; Park, Y.N. Invasion and EMT-associated genes are up-regulated in B viral hepatocellular carcinoma with high expression of CD133-human and cell culture study. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2011, 90, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marumoto, T.; Hirota, T.; Morisaki, T.; Kunitoku, N.; Zhang, D.; Ichikawa, Y.; Sasayama, T.; Kuninaka, S.; Mimori, T.; Tamaki, N.; et al. Roles of aurora-A kinase in mitotic entry and G2 checkpoint in mammalian cells. Genes Cells 2002, 7, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, N.; Pandey, R.K.; Mishra, A.; Kumar, S.; Jha, H.C. Aurora Kinase A: Integrating Insights into Cancer, Inflammation, and Infectious Diseases. Gut Microbes Rep. 2024, 1, 2419069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AURKA Gene—GeneCards. AURKA Protein. AURKA Antibody. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=AURKA (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Magnaghi-Jaulin, L.; Eot-Houllier, G.; Gallaud, E.; Giet, R. Aurora A Protein Kinase: To the Centrosome and Beyond. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisetti, L.; Garcia, C.J.C.; Saponaro, A.A.; Tiribelli, C.; Pascut, D. The role of Aurora kinase A in hepatocellular carcinoma: Unveiling the intriguing functions of a key but still underexplored factor in liver cancer. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H.B.; Mandlik, S.K.; Mandlik, D.S. Role of p53 suppression in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2023, 14, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, R.; Huang, C.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Dong, Z. Targeting AURKA in Cancer: Molecular mechanisms and opportunities for Cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasudhan, E.; Blake, N.; Lu, Z.; Meng, J.; Rong, R. Hepatitis B Viral Protein HBx and the Molecular Mechanisms Modulating the Hallmarks of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2022, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, H.; Sasai, K.; Kawai, H.; Yuan, Z.-M.; Bondaruk, J.; Suzuki, F.; Fujii, S.; Arlinghaus, R.B.; Czerniak, B.A.; Sen, S. Phosphorylation by aurora kinase A induces Mdm2-mediated destabilization and inhibition of p53. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macůrek, L.; Lindqvist, A.; Lim, D.; Lampson, M.A.; Klompmaker, R.; Freire, R.; Clouin, C.; Taylor, S.S.; Yaffe, M.B.; Medema, R.H. Polo-like kinase-1 is activated by aurora A to promote checkpoint recovery. Nature 2008, 455, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, M.; Matthess, Y.; Raab, C.A.; Gutfreund, N.; Dötsch, V.; Becker, S.; Sanhaji, M.; Strebhardt, K. A dimerization-dependent mechanism regulates enzymatic activation and nuclear entry of PLK1. Oncogene 2022, 41, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E.; Soung, N.-K.; Johmura, Y.; Kang, Y.H.; Liao, C.; Lee, K.H.; Park, C.H.; Nicklaus, M.C.; Lee, K.S. Polo-box domain: A versatile mediator of polo-like kinase function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutterer, A.; Berdnik, D.; Wirtz-Peitz, F.; Žigman, M.; Schleiffer, A.; Knoblich, J.A. Mitotic Activation of the Kinase Aurora-A Requires Its Binding Partner Bora. Dev. Cell 2006, 11, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.R.; Sharma, G.; Chakraborty, C.; Kim, J. PLK-1: Angel or devil for cell cycle progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta–Rev. Cancer 2016, 1865, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, K.M.; Henderson, B.R. Characterization of BRCA1 Protein Targeting, Dynamics, and Function at the Centrosome. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 7701–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioniemi, O.-P. Tissue microarray technology for high-throughput molecular profiling of cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, S.; Özsoy, E.R. Aurora Kinases: Their Role in Cancer and Cellular Processes. Türk Doğa Ve Fen Derg. 2024, 13, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, D.L.; He, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Mason, J.T.; O’Leary, T.J. Paraffin Embedding Contributes to RNA Aggregation, Reduced RNA Yield, and Low RNA Quality. J. Mol. Diagn. 2011, 13, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-I.; Wang, C.-C.; Tai, T.-S.; Hwang, T.-Z.; Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-M.; Su, Y.-C. eIF4E and 4EBP1 are prognostic markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma recurrence after definitive surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.-J.; Zhong, Z.-S.; Zhang, L.-S.; Chen, D.-Y.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.-Y. Aurora-A Is a Critical Regulator of Microtubule Assembly and Nuclear Activity in Mouse Oocytes, Fertilized Eggs, and Early Embryos1. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 70, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-Y.; Zheng, Y. Aurora A Kinase-Coated Beads Function as Microtubule-Organizing Centers and Enhance RanGTP-Induced Spindle Assembly. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2156–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhu, Y.; Agopian, V.G.; Tseng, H.; Yang, J.D. Diagnostic Criteria and LI-RADS for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Corrigendum to “EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma [J Hepatol 69 (2018) 182–236]”. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, E.; Fragoulis, A.; Garcia-Alonso, L.; Cramer, T.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Beltrao, P. Widespread Post-transcriptional Attenuation of Genomic Copy-Number Variation in Cancer. Cell Syst. 2017, 5, 386–398.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, H.M.; Jang, B.G.; Hyun, C.L.; Kim, Y.S.; Hyun, J.W.; Chang, W.Y.; Maeng, Y.H. Aurora Kinase A Is a Prognostic Marker in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2017, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Fukuda, Y.; Komeda, T.; Kita, R.; Sando, T.; Furukawa, M.; Amenomori, M.; Shibagaki, I.; Nakao, K.; Ikenaga, M. Amplification and overexpression of the cyclin D1 gene in aggressive human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3107–3110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Hong, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.-M.; Park, C.; Lim, H.Y. An investigation of the role of gene copy number variations in sorafenib sensitivity in metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Li, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Chu, E.; Wei, N. Emerging roles of Aurora-A kinase in cancer therapy resistance. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 2826–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, S.; Isola, J.; Jumppanen, M.; Tanner, M. Aurora-A gene is frequently amplified in basal-like breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 23, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, Y.-M.; Peng, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y.; Hsu, H.-C. Overexpression and Amplification of Aurora-A in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Details. NCT00500903. A Study of MLN8237, a Novel Aurora A Kinase Inhibitor, in Participants with Advanced Solid Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00500903 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Zhang, K.; Wang, T.; Zhou, H.; Feng, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Wang, R. A Novel Aurora-A Inhibitor (MLN8237) Synergistically Enhances the Antitumor Activity of Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralaei, N.; Majd, A.; Ghaedi, K.; Peymani, M.; Safaei, M. Integrated pan-cancer of AURKA expression and drug sensitivity analysis reveals increased expression of AURKA is responsible for drug resistance. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 6428–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.S.K.; Marcus, M.W.; Davies, M.P.A.; Risk, J.M.; Shaw, R.J.; Field, J.K.; Liloglou, T. AURKA mRNA expression is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4463–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, F.J.; Sinilnikova, O.; Vierkant, R.A.; Pankratz, V.S.; Fredericksen, Z.S.; Stoppa-Lyonnet, D.; Coupier, I.; Hughes, D.; Hardouin, A.; Berthet, P.; et al. AURKA F31I Polymorphism and Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, K.; Treekitkarnmongkol, W.; Kai, K.; Katayama, H.; Sen, S. Functional Significance of Aurora Kinases–p53 Protein Family Interactions in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, e1002566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Xiao, B.; Si, H.; Cervini, A.; Gao, J.; Lu, J.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Verma, S.C.; Robertson, E.S. Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpesvirus Upregulates Aurora A Expression to Promote p53 Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, B.; de Cárcer, G.; Ibañez, S.; Bragado-Nilsson, E.; Montoya, G. Molecular and structural basis of polo-like kinase 1 substrate recognition: Implications in centrosomal localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3107–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KY, C.; ED, L.; Sinclair, J.; Nigg, E.A.; Johnson, L.N. The crystal structure of the human polo-like kinase-1 polo box domain and its phospho-peptide complex. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5757–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X. PLK1, A Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 10, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, A.D.; Portmann, B.; Ferrell, L.D.; MacSween, R.N.M. MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 9780702033988. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, P.K.; Yang, E.J.; Shi, C.; Ren, G.; Tao, S.; Shim, J.S. Aurora kinase A, a synthetic lethal target for precision cancer medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Luo, J.; Liu, W.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hu, S.; Shen, X.; Du, X.; Xiang, W. Alisertib impairs the stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting purine synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Luo, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Z.; He, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhou, S. A proteomics-based investigation on the anticancer activity of alisertib, an Aurora kinase A inhibitor, in hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3558–3572. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Pan, F.; Abudoureyimu, M.; Wang, T.; Hao, L.; Wang, R. Aurora-A inhibitor synergistically enhances the inhibitory effect of anlotinib on hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 690, 149247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Histopathologic Feature | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Normal liver tissue. Healthy donor liver sample. | Liver wedge biopsy material. TMA generated from paraffin block. |

| HBV-HCC | HBV-associated HCC cases | Hepatectomy material. TMA paraffin block, generating new tissue microarrays from paraffin block. |

| Cr-HCC | HCC cases that cannot be clinically and serologically associated with any etiology. | Hepatectomy material. TMA paraffin block generating new tissue microarrays from paraffin block. |

| Primer | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| AURKA-F | GCAACCAGTGTACCTCATCCTG |

| AURKA-R | AAGTCTTCCAAAGCCCACTGCC |

| 36B4-F | CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC |

| 36B4-R | CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA |

| Staining Prevalence | Score | Color Depth | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staining rate of cells 0% | 0 | No staining | 0 |

| Staining rate of cells 1–25% | 1 | Weak | 1 |

| Staining rate of cells 25–50% | 2 | Middle | 2 |

| Staining rate of cells 50–75% | 3 | Strong | 3 |

| Staining rate of cells 75–100% | 4 | — | — |

| Variables | HBV-HCC | Cr-HCC | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Minimum–Maximum) | |||

| ∆∆Ct | 6.981 (4.454–9.983) | 6.181 (3.753–8.11) | 0.060 |

| 2−∆∆Ct | 0.1 (0.012–0.577) | 0.174 (0.046–0.938) | 0.060 |

| Median (Minimum–Maximum) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Control Group | HBV-HCC | p Value |

| AURKA | 0 (0–1) | 9 (4–12) | <0.001 * |

| P53Ser315 | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–6) | 0.002 ¥ |

| PLK1Thr210 | 1 (0–6) | 2 (0–8) | 0.296 |

| BRCA1 | 1 (0–2) | 4 (0–8) | 0.006 ₫ |

| Control group | Cr-HCC | p | |

| AURKA | 0 (0–1) | 8 (3–12) | <0.001 * |

| P53Ser315 | 1 (0–2) | 4 (0–9) | <0.001 ¥ |

| PLK1Thr210 | 1 (0–6) | 6 (0–12) | <0.001 Ꝋ |

| BRCA1 | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–4) | 0.239 |

| HBV-HCC | Cr-HCC | p | |

| AURKA | 9 (4–12) | 8 (3–12) | 0.224 |

| P53Ser315 | 2 (0–6) | 4 (0–9) | 0.025 ¥¥ |

| PLK1Thr210 | 2 (0–8) | 6 (0–12) | 0.001 Ꝋ |

| BRCA1 | 4 (0–8) | 1 (0–4) | 0.11 |

| Clinical Scenario | Role of Imaging (LI-RADS) | Indication for Liver Biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| Cirrhotic patient with LI-RADS 5 lesion | Diagnostic | Not required |

| Cirrhotic patient with LI-RADS 3–4 lesion | Indeterminate | May be required for diagnostic confirmation |

| Non-cirrhotic patient | Limited diagnostic specificity | Generally required |

| Atypical imaging features | Insufficient for definitive diagnosis | Required for differential diagnosis |

| Patients considered for systemic chemotherapy | Limited role in treatment selection | May be required for molecular subclassification or target identification |

| Patients considered for immunotherapy | Not diagnostic | May be required for immunophenotypic profiling (e.g., PD-L1, TME) |

| Assessment of treatment response or disease progression | Primary follow-up tool | Selected cases only (suspected resistance or transformation) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huz, M.; Karadag Soylu, N.; Koc, A.; Kucukakcali, Z.; Danis, N.; Ozhan, O. The Role of Aurora Kinase A in HBV-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinomas: A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010160

Huz M, Karadag Soylu N, Koc A, Kucukakcali Z, Danis N, Ozhan O. The Role of Aurora Kinase A in HBV-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinomas: A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010160

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuz, Mustafa, Nese Karadag Soylu, Ahmet Koc, Zeynep Kucukakcali, Nefsun Danis, and Onural Ozhan. 2026. "The Role of Aurora Kinase A in HBV-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinomas: A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010160

APA StyleHuz, M., Karadag Soylu, N., Koc, A., Kucukakcali, Z., Danis, N., & Ozhan, O. (2026). The Role of Aurora Kinase A in HBV-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinomas: A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study. Diagnostics, 16(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010160