A Pilot Study of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Comparative Insights from Culture and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.3. Microbiological Methods

2.4. DNA Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.5. Preparing Libraries and Tngs

2.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. Identification of K. pneumoniae Using MALDI-TOF MS and tNGS

3.2.1. Microbial Co-Detection and Diversity

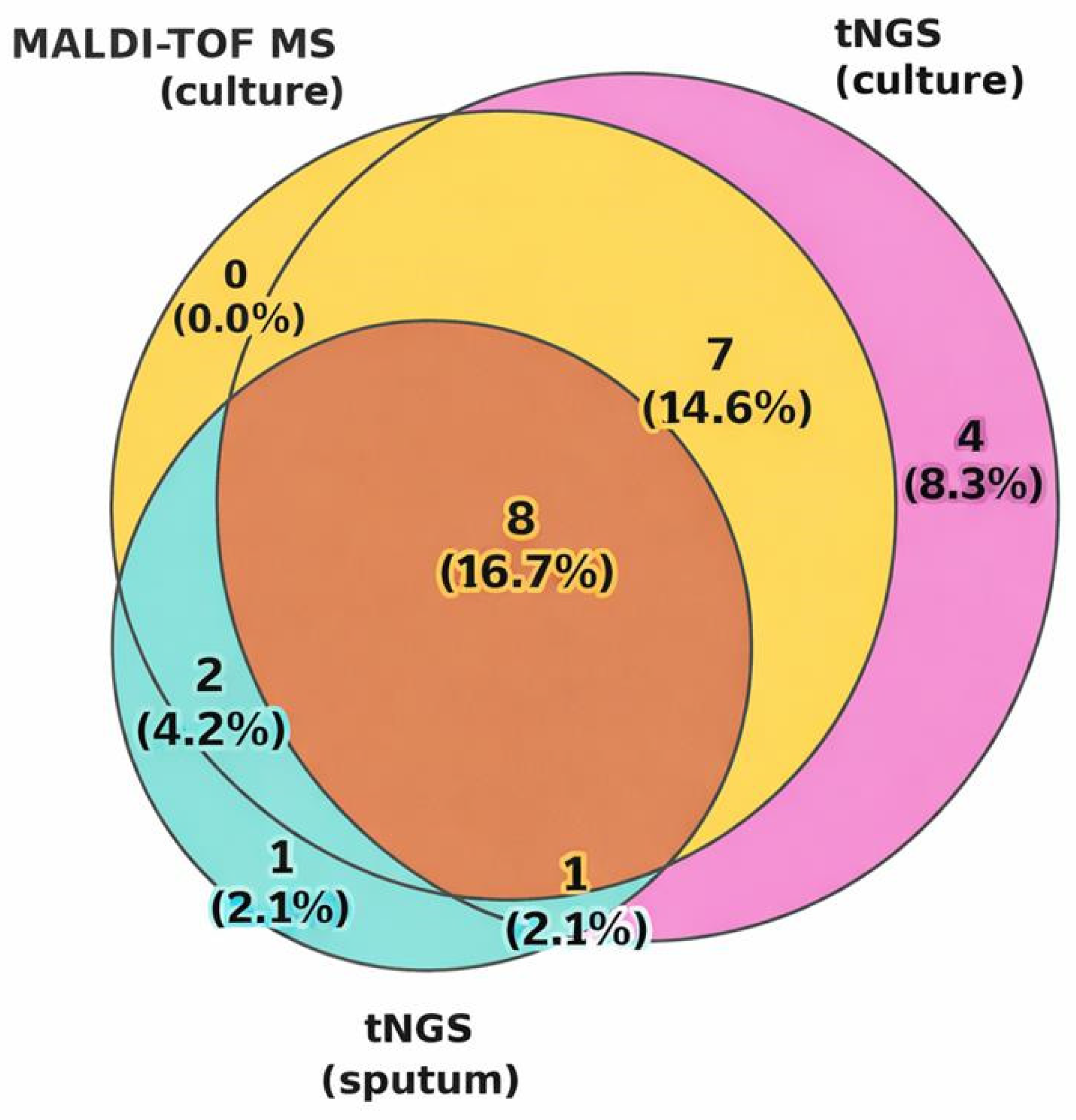

3.2.2. Concordance Analysis

3.3. Comparative Analysis of K. pneumoniae AMR in Sputum and Cultural Samples

3.3.1. Phenotypic Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles

3.3.2. Genotypic–Phenotypic Correlation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Pure Cultures

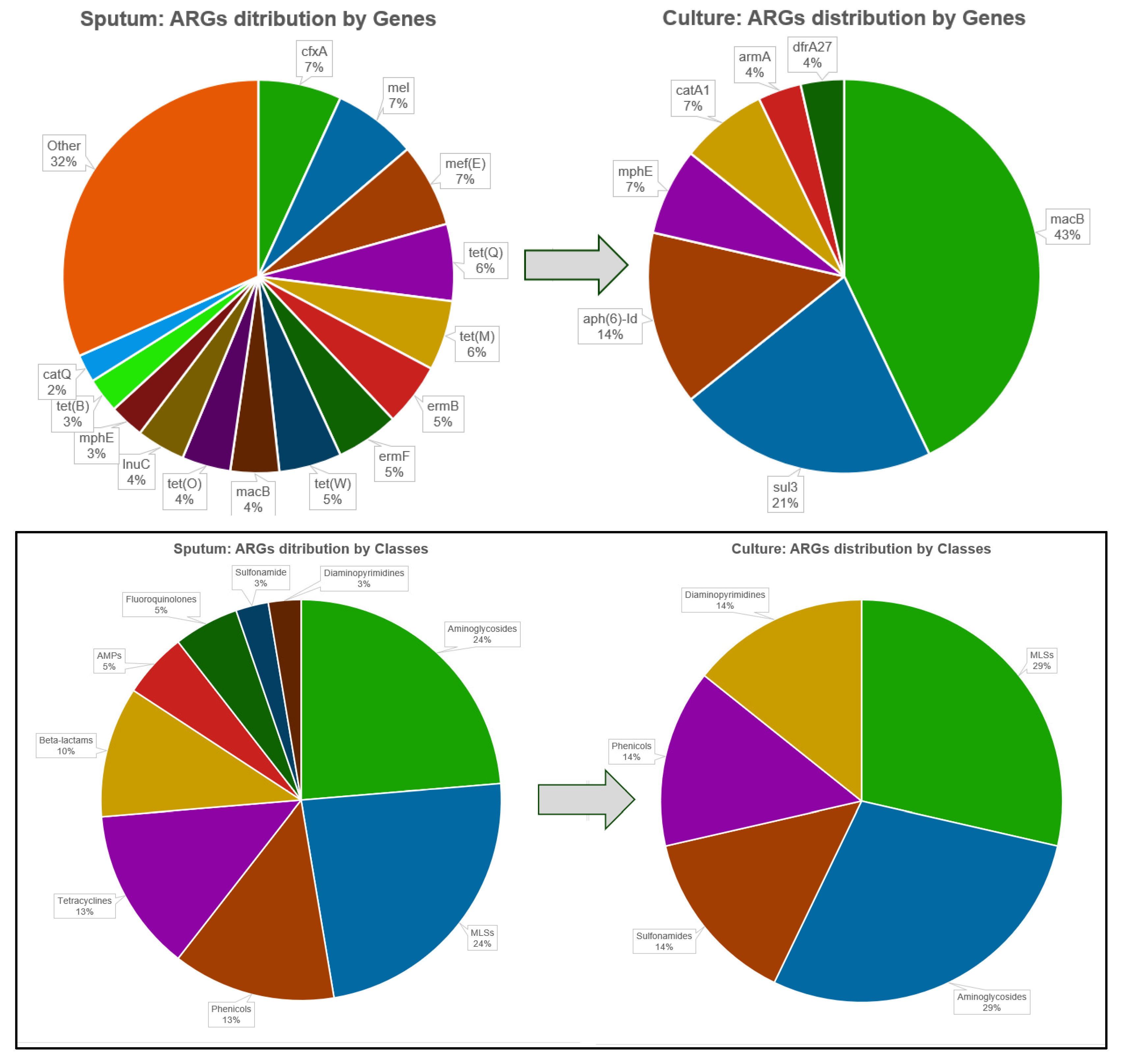

3.3.3. Comparative Analysis of ARG Profiles in Sputum and Pure K. pneumoniae Cultures

3.4. Interesting Findings That Warrant Further Investigation

3.4.1. Divergent Microbial and Resistome Profiles in Fatal CAP Cases

- Case 1: ID 3 (45-year-old male, levofloxacin therapy, death)

- Case 2: ID 32 (60-year-old male, multiple prior antibiotics, death)

3.4.2. Divergent Culture- and Sputum-Based Profiles in CAP Patients

- Case 3: ID 5 (81-year-old male, multiple myeloma, discharged)

- Case 4: Consistent Loss of S. pneumoniae-Associated ARGs

- ID 18: Loss of mef(E) and pbp1A, a penicillin-binding protein in S. pneumoniae that confers resistance to penicillin-class β-lactams and cephalosporins [42].

- ID 24: Loss of mel.

- IDs 46, 49, 51, 59: Loss of both mel and mef(E).

- Case 5: Detection of mecA in Sputum but Not in Culture

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence and Clinical Importance of K. pneumoniae

4.2. Fatal Outcomes and Diagnostic Discordance

4.3. Microbial Diversity and Cultivation Effects

4.4. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns

4.5. Resistome Profiles in Cultures Versus Primary Sputum

4.6. Microbial Shifts Between Sputum and Culture

4.7. Detection of Clinically Significant but Hidden Resistance Markers

4.8. Complementary Roles of Classical Microbiological Methods and tNGS in CAP

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of This Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves-Pereira, J.; Froes, F.; Pereira, F.G.; Diniz, A.; Oliveira, H.; Mergulhão, P. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Mortality Trends According to Age and Gender: 2009 to 2019. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoar, S.; Musher, D.M. Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: A Systematic Review. Pneumonia 2020, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampatakis, T.; Tsergouli, K.; Behzadi, P. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Virulence Factors, Molecular Epidemiology and Latest Updates in Treatment Options. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarras, C.; Karampatakis, T.; Pappa, S.; Iosifidis, E.; Vagdatli, E.; Roilides, E.; Papa, A. Genetic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates in a Tertiary Hospital in Greece, 2018–2022. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Ding, C.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Liu, X. Exploring Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms through Whole Genome Sequencing Analysis. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, A.K.; Vincent, K.; Mohan, G.B.M.; Ramakrishnan, J. Association of Sequence Types, Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes in Indian Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Comparative Genomics Study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 30, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraya, A.; Kyany’a, C.; Kiyaga, S.; Smith, H.J.; Kibet, C.; Martin, M.J.; Kimani, J.; Musila, L. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in Kenya by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Pathogens 2022, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrinenko, A.; Kolesnichenko, S.; Kadyrova, I.; Turmukhambetova, A.; Akhmaltdinova, L.; Klyuyev, D. Bacterial Co-Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance in Patients Hospitalized with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 Pneumonia in Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2023, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, G.; Wang, Y.; Lu, G.; Wu, B.; Chen, W.; Zhou, W. Antimicrobial Resistance Prediction by Clinical Metagenomics in Pediatric Severe Pneumonia Patients. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2024, 23, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaidullina, E.R.; Schwabe, M.; Rohde, T.; Shapovalova, V.V.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Matsvay, A.D.; Savochkina, Y.A.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Sydow, K.; et al. Genomic Analysis of the International High-Risk Clonal Lineage Klebsiella pneumoniae Sequence Type 395. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, V.K.; Kandi, V.; Bharadwaj, V.G.; Suvvari, T.K.; Podaralla, E. Molecular Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates Through Whole-Genome Sequencing: A Comprehensive Analysis of Serotypes, Sequence Types, and Antimicrobial and Virulence Genes. Cureus 2024, 16, e58449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fursova, N.K.; Astashkin, E.I.; Ershova, O.N.; Aleksandrova, I.A.; Savin, I.A.; Novikova, T.S.; Fedyukina, G.N.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Fursov, M.V.; Kuzina, E.S.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Causing Severe Infections in the Neuro-ICU. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, X.; Stålsby Lundborg, C.; Sun, X.; Gu, S.; Dong, H. Clinical and Economic Burden of Carbapenem-Resistant Infection or Colonization Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii: A Multicenter Study in China. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florio, W.; Tavanti, A.; Barnini, S.; Ghelardi, E.; Lupetti, A. Recent Advances and Ongoing Challenges in the Diagnosis of Microbial Infections by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.M.; Timbrook, T.T.; Hommel, B.; Prinzi, A.M. Breaking Boundaries in Pneumonia Diagnostics: Transitioning from Tradition to Molecular Frontiers with Multiplex PCR. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, V.; Ganaie, F.; Nagaraj, G.; Hussain, A.; Ravi Kumar, K.L. Laboratory Based Identification of Pneumococcal Infections: Current and Future. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Miller, S.; Chiu, C.Y. Clinical Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Detection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandybayev, N.; Beloussov, V.; Strochkov, V.; Solomadin, M.; Granica, J.; Yegorov, S. Metagenomic Profiling of Nasopharyngeal Samples from Adults with Acute Respiratory Infection. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandybayev, N.; Beloussov, V.; Strochkov, V.; Solomadin, M.; Granica, J.; Yegorov, S. Next Generation Sequencing Approaches to Characterize the Respiratory Tract Virome. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandybayev, N.T.; Beloussov, V.Y.; Strochkov, V.M.; Solomadin, M.V.; Granica, J.; Yegorov, S. The Nasopharyngeal Virome in Adults with Acute Respiratory Infection. biorxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strochkov, V.; Beloussov, V.; Orkara, S.; Lavrinenko, A.; Solomadin, M.; Yegorov, S.; Sandybayev, N. Genomic Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Pneumonia Patients in Kazakhstan. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Sun, R.; Gu, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, C.; et al. Clinical Application of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Pneumonia Diagnosis among Cancer Patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1497198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Bao, Z.; Chen, W.; Xi, X.; Ge, X.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, P.; Deng, W.; Ding, R.; et al. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Pneumonia: Applications in the Detection of Responsible Pathogens, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Virulence. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; Chang, X.; Zhang, L.; Gu, D.; Zheng, X.; Chen, J.; Xiao, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Clinical Application of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Severe Pneumonia: A Retrospective Review. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstokstraeten, R.; Piérard, D.; Crombé, F.; De Geyter, D.; Wybo, I.; Muyldermans, A.; Seyler, L.; Caljon, B.; Janssen, T.; Demuyser, T. Genotypic Resistance Determined by Whole Genome Sequencing versus Phenotypic Resistance in 234 Escherichia Coli Isolates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Han, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Mai, C.; Deng, Q.; Ren, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, F.; et al. Novel Clinical mNGS-Based Machine Learning Model for Rapid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e01805-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R.; Patel, R. Molecular Diagnostics for Genotypic Detection of Antibiotic Resistance: Current Landscape and Future Directions. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 5, dlad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Fei, Z.; Xiao, P. Methods to Improve the Accuracy of Next-Generation Sequencing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 982111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Zubair, M.; Sergi, C. Sputum Analysis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Raj Raghubanshi, B.; Singh Karki, B.M. Bacteriology of Sputum Samples: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2020, 58, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiman, L.; Waters, V.; LiPuma, J.J.; Hoffman, L.R.; Alby, K.; Zhang, S.X.; Yau, Y.C.; Downey, D.G.; Sermet-Gaudelus, I.; Bouchara, J.-P.; et al. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: Updated Guidance for Processing Respiratory Tract Samples from People with Cystic Fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e00215-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderaro, A.; Chezzi, C. MALDI-TOF MS: A Reliable Tool in the Real Life of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Cai, K.; Yu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Chen, R.; Xu, R.; Yu, M. Evaluation of Three Sample Preparation Methods for the Identification of Clinical Strains by Using Two MALDI-TOF MS Systems. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2021, 56, e4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, e1–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenkov, A.Y.; Trushin, I.V.; Vinogradova, A.G.; Avramenko, A.A.; Sukhorukova, M.V.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Dekhnich, A.V.; Edelstein, M.V.; Kozlov, R.S. AMRmap: An Interactive Web Platform for Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Data in Russia. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 620002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P.; Pramesh, C.S.; Aggarwal, R. Common Pitfalls in Statistical Analysis: Measures of Agreement. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2017, 8, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimozaki, K.; Hayashi, H.; Tanishima, S.; Horie, S.; Chida, A.; Tsugaru, K.; Togasaki, K.; Kawasaki, K.; Aimono, E.; Hirata, K.; et al. Concordance Analysis of Microsatellite Instability Status between Polymerase Chain Reaction Based Testing and next Generation Sequencing for Solid Tumors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen-Torvik, L.J.; Almoguera, B.; Doheny, K.F.; Freimuth, R.R.; Gordon, A.S.; Hakonarson, H.; Hawkins, J.B.; Husami, A.; Ivacic, L.C.; Kullo, I.J.; et al. Concordance between Research Sequencing and Clinical Pharmacogenetic Genotyping in the eMERGE-PGx Study. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 19, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, A.G.; Clark, R.B. Discovery of Macrolide Antibiotics Effective against Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, K.D.; Nisbet, R.; Stephens, D.S. Macrolide Efflux in Streptococcus pneumoniae Is Mediated by a Dual Efflux Pump (Mel. and Mef) and Is Erythromycin Inducible. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 4203–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, M.J.; Lefébure, T.; Walsh, S.L.; Becker, J.A.; Lang, P.; Pavinski Bitar, P.D.; Miller, L.A.; Italia, M.J.; Amrine-Madsen, H. Positive Selection in Penicillin-Binding Proteins 1a, 2b, and 2x from Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Its Correlation with Amoxicillin Resistance Development. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2008, 8, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umami, Z.; Warni, A.I.; Wahyuni, D. Mec Genes in Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Islam. Pharm. 2023, 8, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuda, C.; Suvorov, M.; Vakulenko, S.B.; Mobashery, S. The Basis for Resistance to β-Lactam Antibiotics by Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 40802–40806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Song, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, H. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella: Advances in Detection Methods and Clinical Implications. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, F. Molecular Epidemiology and Drug Resistant Mechanism of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Elderly Patients with Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 669173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Huang, F.; Fang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, H.; Cai, J.; Cui, W.; Chen, C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Klebsiella pneumoniae Pneumonia Developing Secondary Klebsiella pneumoniae Bloodstream Infection. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beviere, M.; Reissier, S.; Penven, M.; Dejoies, L.; Guerin, F.; Cattoir, V.; Piau, C. The Role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in the Management of Tuberculosis: Practical Review for Implementation in Routine. Pathogens 2023, 12, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widder, S.; Carmody, L.A.; Opron, K.; Kalikin, L.M.; Caverly, L.J.; LiPuma, J.J. Microbial Community Organization Designates Distinct Pulmonary Exacerbation Types and Predicts Treatment Outcome in Cystic Fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baichman-Kass, A.; Song, T.; Friedman, J. Competitive Interactions between Culturable Bacteria Are Highly Non-Additive. eLife 2023, 12, e83398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Application of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1458316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angel, N.Z.; Sullivan, M.J.; Alsheikh-Hussain, A.; Fang, L.; MacDonald, S.; Pribyl, A.; Wills, B.; Tyson, G.W.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H.; et al. Metagenomics: A New Frontier for Routine Pathology Testing of Gastrointestinal Pathogens. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawcutt, K.A.; Kalil, A.C. Viral and Bacterial Co-Infection in Pneumonia: Do We Know Enough to Improve Clinical Care? Crit. Care 2017, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Lu, J.; Liu, G.; Mo, L.; Feng, Y.; Tang, W.; Lu, C.; Lu, X.; et al. Pathogen Distribution and Infection Patterns in Pediatric Severe Pneumonia: A Targeted next-Generation Sequencing Study. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 565, 119985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, P.S.; Deshpande, A.; Yu, P.-C.; Klompas, M.; Haessler, S.D.; Imrey, P.B.; Zilberberg, M.D.; Rothberg, M.B. Bacterial Coinfection in Influenza Pneumonia: Rates, Pathogens, and Outcomes. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbauy, G.; Vivan, A.C.; Simões, G.C.; Simionato, A.S.; Pelisson, M.; Vespero, E.C.; Costa, S.F.; Andrade, C.G.; Barbieri, D.M.; Mello, J.C.; et al. Effect of a Metalloantibiotic Produced by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa on Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing K. pneumoniae. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016, 17, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermkaew, N.; Atipairin, A.; Krobthong, S.; Aonbangkhen, C.; Yingchutrakul, Y.; Uchiyama, J.; Songnaka, N. Unveiling a New Antimicrobial Peptide with Efficacy against P. Aeruginosa and K. Pneumoniae from Mangrove-Derived Paenibacillus Thiaminolyticus NNS5-6 and Genomic Analysis. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; Cuellar-Sánchez, A.; Romero-Cerón, A.L.; Rivera-Urbalejo, A.; Van Dillewijn, P.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Bustillos-Cristales, M.D.R. The Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) State, a Poorly Explored Aspect of Beneficial Bacteria. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mendis, N.; Trigui, H.; Oliver, J.D.; Faucher, S.P. The Importance of the Viable but Non-Culturable State in Human Bacterial Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, A.J.; Lysenko, E.S.; Paul, M.N.; Weiser, J.N. Synergistic Proinflammatory Responses Induced by Polymicrobial Colonization of Epithelial Surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 3429–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, H.K.; Shreevatsa, B.; Dharmashekara, C.; Shruthi, G.; Prasad, K.S.; Patil, S.S.; Shivamallu, C. Review of Known and Unknown Facts of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Its Relationship with Antibiotics. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2022, 15, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, A.C.; Striesow, J.; Pané-Farré, J.; Sura, T.; Wurster, M.; Lalk, M.; Pieper, D.H.; Becher, D.; Kahl, B.C.; Riedel, K. An Innovative Protocol for Metaproteomic Analyses of Microbial Pathogens in Cystic Fibrosis Sputum. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 724569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Sharma, L. Challenges in Understanding Lung Microbiome: It Is NOT like the Gut Microbiome. Respirology 2020, 25, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skachkova, T.S.; Shipulina, O.Y.; Shipulin, G.A.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Yanushevich, Y.G.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Zamyatin, M.N.; Gusarov, V.G.; Petrova, N.V.; Lashenkova, N.N.; et al. Characterization of Genetic Diversity of the Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains in a Moscow Tertiary Care Center Using Next-Generation Sequencing. CMAC 2019, 21, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalefa, H.S.; Arafa, A.A.; Hamza, D.; El-Razik, K.A.A.; Ahmed, Z. Emerging Biofilm Formation and Disinfectant Susceptibility of ESBL-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan-Aydogan, O.; Alocilja, E.C. A Review of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales and Its Detection Techniques. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A Prioritisation Study to Guide Research, Development, and Public Health Strategies against Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadpour, D.; Memar, M.Y.; Leylabadlo, H.E.; Ghotaslou, A.; Ghotaslou, R. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Comprehensive Review of Phenotypic and Genotypic Methods for Detection. Microbe 2025, 6, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Xu, Q.; Pan, F.; Shi, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Liu, W.; Pan, X.; Han, D.; et al. Association between Intestinal Colonization and Extraintestinal Infection with Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Children. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04088-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, G.D.; Maukayeva, S.B.; Kudaibergenova, N.K.; Shabdarbayeva, D.M.; Smailova, Z.K.; Tokayeva, A.Z.; Smail, Y.M.; Nuralinova, G.I.; Issabekova, Z.B.; Karimova, S.S.; et al. Analysis of Antibiotic Susceptibility and Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Various Biological Materials. Sci. Healthc. 2025, 27, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00047-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauba, A.; Rahman, K.M. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.C.; Jacoby, G.A. Mechanisms of Drug Resistance: Quinolone Resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1354, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enany, S.; Zakeer, S.; Diab, A.A.; Bakry, U.; Sayed, A.A. Whole Genome Sequencing of Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates Sequence Type 627 Isolated from Egyptian Patients. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, N.; Wang, M.; Gu, B.; Li, J.; Jin, H.; Xiao, W.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; et al. Prevalence of 16S rRNA Methylation Enzyme Gene armA in Salmonella from Outpatients and Food. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 663210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, B.; Falconer, C.; Vatansever, C.; Özer, B.; Çınar, G.; Aslan, A.T.; Forde, B.; Harris, P.; Şimşek, F.; Tülek, N.; et al. High Prevalence of ArmA-16S rRNA Methyltransferase among Aminoglycoside-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Bloodstream Isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreten, V.; Boerlin, P. A New Sulfonamide Resistance Gene (Sul3) in Escherichia coli Is Widespread in the Pig Population of Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sköld, O. Sulfonamide Resistance: Mechanisms and Trends. Drug Resist. Updates 2000, 3, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, N.; Nishino, K.; Hirata, T.; Yamaguchi, A. Membrane Topology of ABC-type Macrolide Antibiotic Exporter MacB in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lu, W.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, G.; Liu, H.; Qian, C.; Zhou, W.; Lu, J.; Ni, L.; Bao, Q.; et al. Characterization of Two Macrolide Resistance-Related Genes in Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alton, N.K.; Vapnek, D. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of the Chloramphenicol Resistance Transposon Tn9. Nature 1979, 282, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, F.E.; Goodman, R.N.; Gallichan, S.; Forrest, S.; Picton-Barlow, E.; Fraser, A.J.; Phan, M.-D.; Mphasa, M.; Hubbard, A.T.M.; Musicha, P.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Re-Emerging Chloramphenicol Susceptibility in Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Q.; Ni, Y. Characterization of Two Novel Gene Cassettes, dfrA27 and aadA16, in a Non-O1, Non-O139 Vibrio Cholerae Isolate from China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, M.; Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Highly Diverse Sputum Microbiota Correlates with the Disease Severity in Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, H.; Peretz, A.; Lesnik, R.; Aizenberg-Gershtein, Y.; Rodríguez-Martínez, S.; Sharaby, Y.; Pastukh, N.; Brettar, I.; Höfle, M.G.; Halpern, M. Comparison of Sputum Microbiome of Legionellosis-Associated Patients and Other Pneumonia Patients: Indications for Polybacterial Infections. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, M.M.; Tanner, W.; Harris, A.D. The Lung Microbiome and Pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, S241–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, S.; Deng, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, Z. Advances in the Oral Microbiota and Rapid Detection of Oral Infectious Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1121737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillóniz, C.; Ewig, S.; Ferrer, M.; Polverino, E.; Gabarrús, A.; Puig De La Bellacasa, J.; Mensa, J.; Torres, A. Community-Acquired Polymicrobial Pneumonia in the Intensive Care Unit: Aetiology and Prognosis. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, K.E.S.; Otsuki, K.; Vicente, A.C.P.; Vieira, J.M.B.D.; De Paula, G.R.; Domingues, R.M.C.P.; Ferreira, M.C.D.S. Presence of the cfxA Gene in Bacteroides Distasonis. Res. Microbiol. 2003, 154, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, M.; Shintani, M. Microbial Evolution through Horizontal Gene Transfer by Mobile Genetic Elements. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; De Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, C.; Pan, P. Next-Generation Sequencing Guides the Treatment of Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia with Empiric Antimicrobial Therapy Failure: A Propensity-Score-Matched Study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piddock, L.J.V. Assess Drug-Resistance Phenotypes, Not Just Genotypes. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, A.; Kayal, T.; Basu, S. Polymicrobial Infections: A Comprehensive Review on Current Context, Diagnostic Bottlenecks and Future Directions. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Steyn, J.; Conceição, E.C.; Wells, F.B.; Grobbelaar, M.; Ismail, N.; Ghebrekristos, Y.; Opperman, C.J.; Singh, S.; Limberis, J.; et al. Matrix-Based DNA Extraction for Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing on Decontaminated Sputum Samples. J. Vis. Exp. 2025, 220, 68147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Tun, H.M.; Jahan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Kumar, A.; Dilantha Fernando, W.G.; Farenhorst, A.; Khafipour, E. Comparison of DNA-, PMA-, and RNA-Based 16S rRNA Illumina Sequencing for Detection of Live Bacteria in Water. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.; O’Sullivan, O.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D. Development of Sequencing-Based Methodologies to Distinguish Viable from Non-Viable Cells in a Bovine Milk Matrix: A Pilot Study. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1036643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 32 (66.7) |

| Female | 16 (33.3) |

| Age | |

| Median (IQR) | 67.0 (55–75) |

| Mean (range) | 63.4 (24–90) |

| Institution | |

| Clinic at the Medical University | 31 (64.6) |

| Hematology Center | 14 (29.2) |

| Cardiology Center | 3 (6.2) |

| Department | |

| Hematology | 17 (35.4) |

| Surgery | 15 (31.3) |

| Pulmonology | 8 (16.7) |

| Medicine | 4 (8.3) |

| Cardiology | 3 (6.3) |

| ICU | 1 (2.1) |

| Primary Diagnosis Categories | |

| CAP only | 15 (31.3) |

| Hematological malignancy + pneumonia | 21 (43.7) |

| Other conditions + pneumonia | 12 (25.0) |

| Specific Hematological Malignancies | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 6 (12.5) |

| Multiple myeloma | 6 (12.5) |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 3 (6.3) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 2 (4.2) |

| Other leukemias | 4 (8.3) |

| Clinical Outcomes | |

| Discharged | 45 (93.8) |

| Death | 3 (6.2) |

| Method | Positive Samples (n) | % of Total (n = 48) |

|---|---|---|

| MALDI-TOF MS, culture | 17 | 35.4 |

| tNGS, culture | 22 | 45.8 |

| tNGS, sputum | 14 | 29.2 |

| All methods | 8 | 16.7 |

| Any method | 26 | 54.2 |

| Microorganisms | MALDI-TOF MS, Culture | tngs, Culture | tngs, Sputum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 | 5 | 11 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 | 1 | - |

| Escherichia coli | - | 1 | 1 |

| Haemophilus influenzae 1 | - | - | 3 |

| Gram-positive | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Streptococcus spp. | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae 1 | - | - | 18 |

| Streptococcus salivarius 1 | - | - | 16 |

| Other | |||

| Neisseria meningitidis 1 | - | - | 6 |

| Totals | |||

| Number of distinct species | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Mean microorganisms/sample | 1.15 | 1.42 | 3.04 |

| Comparable Methods | Concordance Rate, % (K) |

|---|---|

| MALDI-TOF MS and tNGS (culture) | 85.4 (K = 0.712; p = 1.05 × 10−6) |

| tNGS (culture) and tNGS (sputum) | 64.6 (K = 0.279; p = 0.029) |

| MALDI-TOF MS and tNGS (sputum) | 72.9 (K = 0.3834; p = 0.0094) |

| All three methods | 31.2 |

| Parameter | Cultivation + MALDI-TOF MS + DDM (AST) | tNGS |

|---|---|---|

| Turnaround time | 72–144 h | 24–48 h |

| Detects | Viable bacteria; dominant isolate; phenotypic resistance | DNA from viable + non-viable organisms; predefined taxa and ARGs |

| Strengths | Species confirmation; phenotypic AST; MIC-based therapy; recovery of isolates | Early broad detection; polymicrobial communities; fastidious organisms; ARG identification |

| Limitations | Requires growth; may miss minority/fastidious species; slower turnaround | Cannot assess viability; limited to panel targets; genotype–phenotype gaps; requires sequencing infrastructure |

| Optimal use | Definitive diagnosis; AST-guided therapy; epidemiology | Early pathogen/ARG detection; culture-negative cases; polymicrobial and pretreated infections |

| Role in CAP management | Essential for final confirmation and susceptibility | Complementary tool improving early decision-making and stewardship |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Beloussov, V.; Strochkov, V.; Sandybayev, N.; Lavrinenko, A.; Solomadin, M. A Pilot Study of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Comparative Insights from Culture and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010154

Beloussov V, Strochkov V, Sandybayev N, Lavrinenko A, Solomadin M. A Pilot Study of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Comparative Insights from Culture and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010154

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeloussov, Vyacheslav, Vitaliy Strochkov, Nurlan Sandybayev, Alyona Lavrinenko, and Maxim Solomadin. 2026. "A Pilot Study of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Comparative Insights from Culture and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010154

APA StyleBeloussov, V., Strochkov, V., Sandybayev, N., Lavrinenko, A., & Solomadin, M. (2026). A Pilot Study of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Comparative Insights from Culture and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. Diagnostics, 16(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010154