Integrated Cross-Platform Analysis Reveals Candidate Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium-Defined Loci Associated with Osteoporosis in Korean Postmenopausal Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

- •

- Illumina Infinium HumanExome BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) group: 98 healthy controls and 191 low BMD cases (total n = 289).

- •

- Affymetrix Axiom Exome Array group: 99 healthy controls and 194 low BMD cases (total n = 293).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Linkage Disequilibrium Block Analysis and SNP Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Subjects

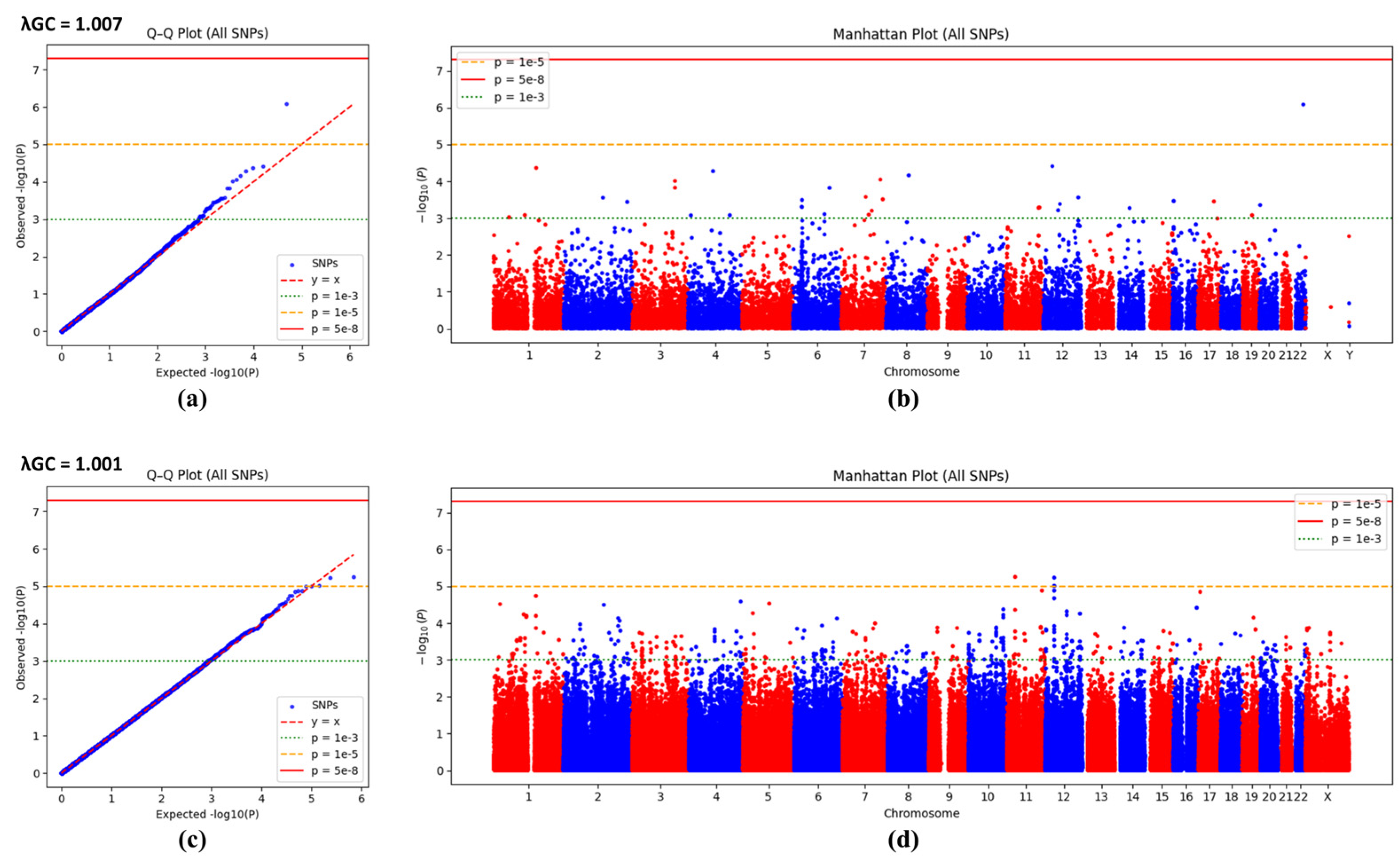

3.2. Q-Q Plots and Manhattan Plots of Logistic Regression

3.3. Overlapping SNPs Across Two Genotyping Platforms (111 SNPs Across 70 Genes)

3.4. Top SNP Selection via Multiple Machine Learning Models

3.5. Predicted Deleterious Non-Synonymous SNPs Identified Across Both Platforms by Multiple in Silico Algorithms

3.6. Conservation Analysis

3.7. Post Hoc Power and Minimum Detectable Effect Size Analysis

3.8. Protein–Protein Interactions and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3.9. LD Block Analysis and Cross-Platform Locus Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KoGES | Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| LD | Linkage Disequilibrium |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| QC | Quality Control |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| PLINK | Persistent Linked INtegrated Kit |

| GERP++ | Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling |

| phyloP | Phylogenetic p-value (phylogenetic conservation score) |

| phastCons | Phylogenetic Hidden Markov Model Conservation Score |

| CADD | Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion |

| SIFT | Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant |

| PROVEAN | Protein Variation Effect Analyzer |

| REVEL | Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner |

| STRING | Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| DAVID | Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery |

| MCL | Markov Cluster Algorithm |

| DR-SOS | Distal Radius Speed of Sound |

| DR-T | Distal Radius T-score |

| DR-Z | Distal Radius Z-score |

| MT-SOS | Midshaft Tibia Speed of Sound |

| MT-T | Midshaft Tibia T-score |

| MT-Z | Midshaft Tibia Z-score |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| Q-Q plots | Quantile-Quantile plots |

Appendix A

| Chr | Chip ID | rs ID | CHR | Pos | Gene | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | exm2249926 | rs55877187 | 1 | 151230929 | PSMD4 | Silent |

| 1 | SNP_A-2293176 | rs11204791 | 1 | 151240542 | ||

| 1 | SNP_A-1966584 | rs6587562 | 1 | 151246241 | ||

| 2 | SNP_A-1884547 | rs2356967 | 2 | 193068151 | ||

| 2 | SNP_A-2237714 | rs2592273 | 2 | 193093850 | ||

| 2 | SNP_A-4256617 | rs2356971 | 2 | 193101110 | ||

| 3 | exm359040 | rs3732765 | 3 | 151090424 | MED12L, P2RY12 | Missense_R1210Q, Silent |

| 3 | exm2265629 | rs9859538 | 3 | 151090963 | MED12L, P2RY12 | Silent |

| 3 | SNP_A-1974833 | rs3821663 | 3 | 151100677 | MED12L | |

| 3 | SNP_A-4205327 | rs10935840 | 3 | 151101083 | MED12L | |

| 3 | SNP_A-4217243 | rs17204501 | 3 | 151114889 | MED12L | |

| 3 | SNP_A-2166335 | rs17204508 | 3 | 151115204 | MED12L | |

| 3 | SNP_A-4203518 | rs4680406 | 3 | 151116816 | MED12L | |

| 3 | SNP_A-2041875 | rs2276765 | 3 | 151131222 | MED12L | |

| 5 | SNP_A-2221307 | rs893547 | 5 | 92776972 | ||

| 5 | SNP_A-1862456 | rs2344386 | 5 | 92848652 | ||

| 10 | SNP_A-2150516 | rs2148476 | 10 | 122175555 | ||

| 10 | SNP_A-2043377 | rs2420717 | 10 | 122175979 | ||

| 10 | SNP_A-4303428 | rs1326663 | 10 | 122179526 | ||

| 10 | SNP_A-2159301 | rs10886690 | 10 | 122213646 | PPAPDC1A | |

| 11 | SNP_A-2268822 | rs1914475 | 11 | 28749414 | ||

| 11 | SNP_A-1856716 | rs10835398 | 11 | 28759826 | ||

| 12 | SNP_A-2258849 | rs1798255 | 12 | 32287259 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | exm2267339 | rs2608405 | 12 | 32296621 | BICD1 | Silent |

| 12 | SNP_A-2138255 | rs4931615 | 12 | 32303400 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1898535 | rs4931616 | 12 | 32303456 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-4301892 | rs2630578 | 12 | 32305787 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-4278412 | rs161962 | 12 | 32360803 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-4283755 | rs161961 | 12 | 32361233 | BICD1 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1863901 | rs4017759 | 12 | 77771495 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2225499 | rs1880881 | 12 | 77772555 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2174026 | rs1527063 | 12 | 77782433 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1799650 | rs4761376 | 12 | 77786244 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1829924 | rs1465070 | 12 | 77790549 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2229564 | rs2011194 | 12 | 77799416 | NAV2 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1793840 | rs11057394 | 12 | 124407676 | DNAH10 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1888303 | rs11057401 | 12 | 124427306 | CCDC92 | |

| 12 | exm1049349 | rs11057401 | 12 | 124427306 | CCDC92 | Missense_S70C |

| 12 | SNP_A-2035335 | rs4765219 | 12 | 124440110 | CCDC92 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2209355 | rs7305864 | 12 | 124441880 | CCDC92 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1821027 | rs6488914 | 12 | 124447841 | CCDC92 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2163277 | rs4765127 | 12 | 124460167 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | exm-rs4765127 | rs4765127 | 12 | 124460167 | ZNF664 | Silent |

| 12 | SNP_A-2288649 | rs12311114 | 12 | 124460703 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2267281 | rs4765528 | 12 | 124462254 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2296376 | rs11057408 | 12 | 124464836 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-4238292 | rs7978610 | 12 | 124468572 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1787908 | rs7311969 | 12 | 124470333 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2079815 | rs7311233 | 12 | 124475940 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2194556 | rs4765148 | 12 | 124478637 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1867568 | rs4765568 | 12 | 124479161 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-4204952 | rs11057409 | 12 | 124479331 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-1961399 | rs7975482 | 12 | 124481690 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2058919 | rs1187415 | 12 | 124491529 | ZNF664 | |

| 12 | SNP_A-2222659 | rs7307053 | 12 | 124494540 | ZNF664 | |

References

- Kanis, J.A. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: Synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos. Int. 1994, 4, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Melton, L.J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 2002, 359, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Nguyen, T.V.; Howard, G.M.; Kelly, P.J.; Eisman, J.A. Genetic and environmental correlations between bone formation and bone mineral density: A twin study. Bone 1998, 22, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajanoska, K.; Morris, J.A.; Oei, L.; Zheng, H.F.; Evans, D.M.; Kiel, D.P.; Ohlsson, C.; Richards, J.B.; Rivadeneira, F.; GEFOS/GENOMOS consortium and the 23andMe research team; et al. Assessment of the genetic and clinical determinants of fracture risk: Genome wide association and mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 2018, 362, k3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Park, H.; Zhang, L.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.A.; Yang, J.Y.; Pei, Y.F.; Tian, Q.; Shen, H.; Hwang, J.Y.; et al. Genome-wide association study in East Asians suggests UHMK1 as a novel bone mineral density susceptibility gene. Bone 2016, 91, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.S.; Im, S.W.; Kang, M.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, B.L.; Park, J.H.; Nam, Y.S.; Son, H.Y.; Yang, S.D.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Bone Mineral Density in Korean Men. Genom. Inf. 2016, 14, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, B. Personal genomes: The case of the missing heritability. Nature 2008, 456, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Abecasis, G.R.; Boehnke, M.; Lin, X. Rare-variant association analysis: Study designs and statistical tests. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 95, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, C.M.; Baranzini, S.E.; Mevik, B.H.; Bos, S.D.; Harbo, H.F.; Andreassen, B.K. Assessing the Power of Exome Chips. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi-Man, O.; Woehrmann, M.H.; Webster, T.A.; Gollub, J.; Bivol, A.; Keeble, S.M.; Aull, K.H.; Mittal, A.; Roter, A.H.; Wong, B.A.; et al. Novel genotyping algorithms for rare variants significantly improve the accuracy of Applied Biosystems Axiom array genotyping calls: Retrospective evaluation of UK Biobank array data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.H.; Shao, Y.J.; Mao, C.L.; Hung, M.N.; Lo, Y.Y.; Ko, T.M.; Hsiao, T.H. A Novel Quality-Control Procedure to Improve the Accuracy of Rare Variant Calling in SNP Arrays. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 736390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weedon, M.N.; Jackson, L.; Harrison, J.W.; Ruth, K.S.; Tyrrell, J.; Hattersley, A.T.; Wright, C.F. Use of SNP chips to detect rare pathogenic variants: Retrospective, population based diagnostic evaluation. BMJ 2021, 372, n214, Correction in BMJ 2021, 372, n792. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Brown, M.A.; McCarthy, M.I.; Yang, J. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Schaffner, S.F.; Nguyen, H.; Moore, J.M.; Roy, J.; Blumenstiel, B.; Higgins, J.; DeFelice, M.; Lochner, A.; Faggart, M.; et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 2002, 296, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, F.; Gonzalez-Macias, J.; Diez-Perez, A.; Palma, S.; Delgado-Rodriguez, M. Relationship between bone quantitative ultrasound and fractures: A meta-analysis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2006, 21, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, H.J. High dairy products intake reduces osteoporosis risk in Korean postmenopausal women: A 4 year follow-up study. Nutr. Res. Pr. 2018, 12, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, S.N.; Leslie, W.D.; Schousboe, J.T. Osteoporosis: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Pettersson, F.H.; Clarke, G.M.; Cardon, L.R.; Morris, A.P.; Zondervan, K.T. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, D.; Dudek, S.; Ritchie, M.D.; Pendergrass, S.A. Visualizing genomic information across chromosomes with PhenoGram. BioData Min. 2013, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhi, D.; Wang, K.; Liu, X. MetaRNN: Differentiating rare pathogenic and rare benign missense SNVs and InDels using deep learning. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.L.; Kumar, P.; Hu, J.; Henikoff, S.; Schneider, G.; Ng, P.C. SIFT web server: Predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W452–W457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Chan, A.P. PROVEAN web server: A tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2745–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, N.M.; Rothstein, J.H.; Pejaver, V.; Middha, S.; McDonnell, S.K.; Baheti, S.; Musolf, A.; Li, Q.; Holzinger, E.; Karyadi, D.; et al. REVEL: An Ensemble Method for Predicting the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense Variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentzsch, P.; Witten, D.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D886–D894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davydov, E.V.; Goode, D.L.; Sirota, M.; Cooper, G.M.; Sidow, A.; Batzoglou, S. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1001025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, K.S.; Hubisz, M.J.; Rosenbloom, K.R.; Siepel, A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.A.O.; de Andrade, E.S.; Palmero, E.I. Insights on variant analysis in silico tools for pathogenicity prediction. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1010327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanis, J.A.; Gluer, C.C. An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Osteoporos. Int. 2000, 11, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, P.; Cizza, G.; Bjarnason, N.H.; Thompson, D.; Daley, M.; Wasnich, R.D.; McClung, M.; Hosking, D.; Yates, A.J.; Christiansen, C. Low body mass index is an important risk factor for low bone mass and increased bone loss in early postmenopausal women. Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort (EPIC) study group. J. Bone Min. Res. 1999, 14, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultation, W.H.O.E. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, E.; Delmas, P.D. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2250–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, I.; Yelensky, R.; Altshuler, D.; Daly, M.J. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet. Epidemiol. 2008, 32, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.; Huang, Y.S.; Ma, C.C.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tsai, H.C.; Yeh, H.Y.; Shen, H.C.; Hong, S.Y.; Su, C.W.; Yang, H.I.; et al. GCKR Polymorphisms Increase the Risks of Low Bone Mineral Density in Young and Non-Obese Patients With MASLD and Hyperuricemia. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2025, 41, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, E.P.; Rhee, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Park, J.W. Identification of pleiotropic genetic variants affecting osteoporosis risk in a Korean elderly cohort. J. Bone Min. Metab. 2019, 37, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Ikari, K.; Terao, C.; Kochi, Y.; Ohmura, K.; Higasa, K.; Akiyama, M.; Ashikawa, K.; Kanai, M.; et al. Contribution of a Non-classical HLA Gene, HLA-DOA, to the Risk of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, N.J.; Sawa, A. Linking neurodevelopmental and synaptic theories of mental illness through DISC1. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, M.; Schoorlemmer, J.; Williams, A.; Diwakar, S.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Giza, J.; Tchetchik, D.; Kelley, K.; Vega, A.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors control neuronal excitability through modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 2007, 55, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pandey, A.K.; Mulligan, M.K.; Williams, E.G.; Mozhui, K.; Li, Z.; Jovaisaite, V.; Quarles, L.D.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, J.; et al. Joint mouse-human phenome-wide association to test gene function and disease risk. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, G.; Inouye, M. Genomic risk prediction of complex human disease and its clinical application. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 33, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbrecht, M.W.; Noble, W.S. Machine learning applications in genetics and genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Chen, X.; Lu, L.; Yuan, F.; Zeng, W.; Luo, S.; Yin, F.; Cai, J. Identification of crucial genes related to postmenopausal osteoporosis using gene expression profiling. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Tytell, J.D.; Ingber, D.E. Mechanotransduction at a distance: Mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonewald, L.F. Mechanosensation and Transduction in Osteocytes. Bonekey Osteovision 2006, 3, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Du, W.; Song, D.; Lu, H.; Hamblin, M.H.; Wang, C.; Du, C.; Fan, G.C.; Becker, R.C.; Fan, Y. Genetic ablation of diabetes-associated gene Ccdc92 reduces obesity and insulin resistance in mice. iScience 2023, 26, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.J. Emerging mechanisms of dynein transport in the cytoplasm versus the cilium. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, S. Cilia/Ift protein and motor -related bone diseases and mouse models. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2015, 20, 515–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.J.; Collier, A.C.; Bowen, L.D.; Pritsos, K.L.; Goodrich, G.G.; Arger, K.; Cutter, G.; Pritsos, C.A. Polymorphisms in the NQO1, GSTT and GSTM genes are associated with coronary heart disease and biomarkers of oxidative stress. Mutat. Res. 2009, 674, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Majumdar, A.; Li, X.; Adler, J.; Sun, Z.; Vertuani, S.; Hellberg, C.; Mellberg, S.; Koch, S.; Dimberg, A.; et al. VE-PTP regulates VEGFR2 activity in stalk cells to establish endothelial cell polarity and lumen formation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genomes Project, C.; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; Zhang, Q.; Sklar, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brown, M.A.; Yang, J. 10 Years of GWAS Discovery: Biology, Function, and Translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control | Low BMD | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age (years) | 53.99 ± 4.55 | 58.09 ± 4.24 | 0.000 |

| age at menopausal (years) | 49.59 ± 2.87 | 49.47 ± 3.8 | >0.05 |

| weight (kg) | 64.05 ± 5.15 | 65.54 ± 6.88 | 0.034 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.98 ± 2.35 | 27.57 ± 2.88 | 0.000 |

| alcohol consumption (g/day) | 0.59 ± 1.4 | 0.57 ± 1.55 | >0.05 |

| calcium consumption (mg/day) | <1000 | <1000 | - |

| DR-SOS (m/s) | 4200.76 ± 118.27 | 4000.31 ± 177.36 | >0.05 |

| DR-T (m/s) | 0.3 ± 0.9 | −1.29 ± 1.46 | >0.05 |

| DR-Z (m/s) | 1.12 ± 1.09 | 0.1 ± 1.39 | >0.05 |

| MT-SOS (m/s) | 3936.63 ± 61.31 | 3625.35 ± 122.15 | 0.000 |

| MT-T (m/s) | −0.2 ± 0.59 | −3.24 ± 1.19 | 0.000 |

| MT-Z (m/s) | 0.59 ± 0.73 | −1.92 ± 1.32 | 0.000 |

| Chr | n | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | KIF1B, ZYG11A, PROK1, DISC1 |

| 2 | 6 | NRXN1, MARCO, CWC22, MAP2 |

| 3 | 11 | C3orf77, COL6A5, ATR, CPB1, GFM1, FGF12 |

| 4 | 3 | DGKQ, SORBS2 |

| 5 | 6 | PDZD2, C7, IQGAP2 |

| 6 | 16 | NRM, NOTCH4, HLA-DOA, BTBD9, THEMIS, LAMA2, SYNE1 |

| 7 | 2 | ASNS |

| 8 | 5 | SLC18A1, C8orf86, UBXN2B, FAM135B |

| 9 | 10 | KDM4C, ACER2, ZNF510, TNFSF15, CERCAM, SETX |

| 10 | 4 | KIAA1217, NRG3, SH3PXD2A |

| 11 | 6 | OSBPL5, DNHD1, MMP13, DYNC2H1 |

| 12 | 12 | CLECL1, SLC4A8, MYO1A, PTPRB, C12orf64, CCDC63, WDR66, GPR81, CCDC92, ZNF664 |

| 13 | 4 | SLC46A3 |

| 14 | 3 | OTX2 |

| 15 | 2 | TNFAIP8L3, LINS |

| 16 | 3 | TRAP1, NQO1, ADAMTS18 |

| 17 | 3 | DLG4, ATAD5 |

| 18 | 0 | |

| 19 | 1 | |

| 20 | 3 | RNF114 |

| 21 | 1 | URB1 |

| X | 0 | |

| Y | 0 |

| LDA | Random Forest | XGBoost | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rsID | Gene | Coefficient | rsID | Gene | Importance | rsID | Gene | Importance | |

| Illumina Infinium HumanExome BeadChip | rs11657270 | ATAD5 | 2.61222 | rs2584021 | PTPRB | 0.012048 | rs11248060 | DGKQ | 0.01788 |

| rs4263839 | TNFSF15 | 0.424226 | rs9554742 | 0.011968 | rs8134971 | URB1 | 0.017365 | ||

| rs4758423 | DNHD1 | 0.38457 | rs11124754 | 0.011813 | rs1049674 | ASNS | 0.016935 | ||

| rs11057401 | CCDC92 | 0.378416 | rs10109439 | FAM135B | 0.011802 | rs6478108 | TNFSF15 | 0.016367 | |

| rs3129304 | HLA-DOA | 0.260162 | rs557135 | 0.011747 | rs10253361 | 0.015085 | |||

| rs1049674 | ASNS | −0.254866 | rs4406360 | 0.011317 | rs4679621 | 0.014259 | |||

| rs4633449 | DNHD1 | −0.356667 | rs4947122 | 0.011187 | rs6556756 | 0.014067 | |||

| rs6478108 | TNFSF15 | −0.433349 | rs6556756 | 0.011181 | rs589623 | DYNC2H1 | 0.013548 | ||

| rs4765127 | ZNF664 | −0.436117 | rs1169081 | WDR66 | 0.011081 | rs10964136 | ACER2 | 0.013402 | |

| rs3816780 | ATAD5 | −2.322621 | rs10490924 | 0.011063 | rs763318 | 0.013336 | |||

| Affymetrix Axiom Exome Array | rs11057401 | CCDC92 | 1.099642 | rs2008344 | TRAP1 | 0.013578 | rs10124818 | 0.021613 | |

| rs11657270 | ATAD5 | 0.777047 | rs7305599 | SLC4A8 | 0.013159 | rs2229032 | ATR | 0.019727 | |

| rs4633449 | DNHD1 | 0.437324 | rs7514102 | PROK1 | 0.01289 | rs629648 | THEMIS | 0.018916 | |

| rs4263839 | TNFSF15 | 0.393153 | rs4758540 | OSBPL5 | 0.012731 | rs4633449 | DNHD1 | 0.015453 | |

| rs11247226 | LINS | 0.315041 | rs10253361 | 0.012213 | rs353372 | 0.014661 | |||

| rs6478108 | TNFSF15 | −0.459254 | rs8134971 | URB1 | 0.012191 | rs6033098 | 0.014627 | ||

| rs2229032 | ATR | −0.525691 | rs10109439 | FAM135B | 0.011849 | rs6795735 | 0.014511 | ||

| rs4758423 | DNHD1 | −0.567479 | rs12033321 | 0.011474 | rs763318 | 0.013953 | |||

| rs3816780 | ATAD5 | −0.896848 | rs1009850 | CERCAM | 0.011446 | rs10253361 | 0.013829 | ||

| rs4765127 | ZNF664 | −1.089067 | rs1169081 | WDR66 | 0.011368 | rs10748869 | NRG3 | 0.013601 | |

| SNP ID | Chr | Pos | Gene | Amino Acid Change | SIFT | Polyphen2 HDIV | Polyphen2 HVAR | PROVEAN | REVEL | CADD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Pred | Score | Pred | Score | Pred | Score | Pred | Score | Phred | |||||

| rs10490924 | 10 | 122,454,932 | ARMS2 | p.Ala69Ser | 0 | D | 0.994 | D | 0.957 | D | −2.63 | D | 0.061 | 15.87 |

| rs11057401 | 12 | 123,942,759 | CCDC92 | p.Ser70Cys | 0.005 | D | 1 | D | 0.971 | D | −2.44 | N | 0.164 | 23.3 |

| rs1800566 | 16 | 69,711,242 | NQO1 | p.Pro187Ser | 0.032 | D | 0.438 | B | 0.167 | B | −7.39 | D | 0.366 | 24 |

| rs2289651 | 9 | 96,774,789 | ZNF510 | p.Gln43Pro | 0.01 | D | 0.838 | P | 0.202 | B | −3.65 | D | 0.128 | 22.2 |

| rs2584021 | 12 | 70,635,953 | PTPRB | p.Asp57Tyr | 0.004 | D | 0.978 | D | 0.77 | P | −1.12 | N | 0.214 | 20.7 |

| rs589623 | 11 | 103,211,861 | DYNC2H1 | p.Arg2871Pro | 0.015 | D | 0.991 | D | 0.964 | D | −4.2 | D | 0.301 | 27.4 |

| SNP ID | Chr | Pos | Gene | GERP++ | phyloP (V) | phyloP (M) | phyloP (P) | phastCons (V) | phastCons (M) | phastCons (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs9284879 | 3 | 44,243,092 | TOPAZ1 | 2.96 | 1.407 | 2.166 | −0.106 | 0.928 | 1 | 0.975 |

| rs2289651 | 9 | 96,774,789 | ZNF510 | 1.52 | 1.944 | −2.174 | 0.665 | 0.999 | 0 | 0.963 |

| rs10490924 | 10 | 122,454,932 | ARMS2 | 0.998 | 0.215 | 0.618 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.025 | |

| rs589623 | 11 | 103,211,861 | DYNC2H1 | 5.76 | 4.414 | 0.676 | 1 | 1 | 0.997 | |

| rs11057401 | 12 | 123,942,759 | CCDC92 | 3.44 | 3.005 | 1.763 | 0.661 | 1 | 1 | 0.995 |

| rs2584021 | 12 | 70,635,953 | PTPRB | 3.92 | 0.98 | 0.848 | 0.599 | 0.763 | 0.446 | 0.947 |

| rs1800566 | 16 | 69,711,242 | NQO1 | 5.41 | 9.295 | 8.644 | 0.676 | 1 | 1 | 0.997 |

| Cluster | Gene Count | Primary Description | Protein Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | Kinesin binding | KIF1B, DLG4, PTPRB, MAP2, SYNE1, DISC1, NRG3, NRXN1, PDZD2 |

| 2 | 4 | miscellaneous | SETX, THEMIS, ATR, ATAD5 |

| 3 | 4 | miscellaneous | TRAP1, GFM1, KIAA1217, CWC22 |

| 4 | 2 | Mixed, incl. Domain of unknown function DUF4537, and CCDC92/74, N-terminal | CCDC92, ZNF664 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, S.K.; Hong, S.-J.; Song, S.I.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, G.; Choi, B.-J.; Seon, S.; Kim, S.J.; Ban, J.Y.; Kang, S.W. Integrated Cross-Platform Analysis Reveals Candidate Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium-Defined Loci Associated with Osteoporosis in Korean Postmenopausal Women. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010153

Kim SK, Hong S-J, Song SI, Lee JK, Kim G, Choi B-J, Seon S, Kim SJ, Ban JY, Kang SW. Integrated Cross-Platform Analysis Reveals Candidate Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium-Defined Loci Associated with Osteoporosis in Korean Postmenopausal Women. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Su Kang, Seoung-Jin Hong, Seung Il Song, Jeong Keun Lee, Gyutae Kim, Byung-Joon Choi, Suyun Seon, Seung Jun Kim, Ju Yeon Ban, and Sang Wook Kang. 2026. "Integrated Cross-Platform Analysis Reveals Candidate Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium-Defined Loci Associated with Osteoporosis in Korean Postmenopausal Women" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010153

APA StyleKim, S. K., Hong, S.-J., Song, S. I., Lee, J. K., Kim, G., Choi, B.-J., Seon, S., Kim, S. J., Ban, J. Y., & Kang, S. W. (2026). Integrated Cross-Platform Analysis Reveals Candidate Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium-Defined Loci Associated with Osteoporosis in Korean Postmenopausal Women. Diagnostics, 16(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010153