The Use of CSF Multiplex PCR Panel in Patients with Viral Uveitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Diagnostic Procedures

2.3. Patient Classification

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Viral Pathogen Distribution

3.3. Subgroup Analysis in Anterior Uveitis (Group I)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| ARN | acute retinal necrosis |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| VZV | varicella-zoster virus |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| HHV | human herpesvirus |

| SUN | standardization of uveitis nomenclature |

| KPs | keratic precipitates |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Darrell, R.W. Epidemiology of Uveitis: Incidence and Prevalence in a Small Urban Community. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1962, 68, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, L. Population Based Assessment of Uveitis in an Urban Population in Southern India. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, N.J.S.; Rathinam, S.R.; Cunningham, E.T. The Epidemiology of Uveitis in Developing Countries. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2010, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.-C.; Shen, D.; Tuo, J. Polymerase Chain Reaction in the Diagnosis of Uveitis. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2005, 45, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, K.; Muccioli, C.; Belfort Junior, R.; Rizzo, L.V. Correlation between Clinical Diagnosis and PCR Analysis of Serum, Aqueous, and Vitreous Samples in Patients with Inflammatory Eye Disease. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2007, 70, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siverio, C.D.; Imai, Y.; Cunningham, E.T. Diagnosis and Management of Herpetic Anterior Uveitis. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2002, 42, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekri, S.; Barzanouni, E.; Samiee, S.; Soheilian, M. Polymerase Chain Reaction Test for Diagnosis of Infectious Uveitis. Int. J. Retina Vitr. 2023, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothova, A.; De Boer, J.H.; Ten Dam-van Loon, N.H.; Postma, G.; De Visser, L.; Zuurveen, S.J.; Schuller, M.; Weersink, A.J.L.; Van Loon, A.M.; De Groot-Mijnes, J.D.F. Usefulness of Aqueous Humor Analysis for the Diagnosis of Posterior Uveitis. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnifro, E.M.; Ashshi, A.M.; Cooper, R.J.; Klapper, P.E. Multiplex PCR: Optimization and Application in Diagnostic Virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, S.; Shimizu, N.; Watanabe, K.; Mizukami, M.; Morio, T.; Sugamoto, Y.; Mochizuki, M. Use of Multiplex PCR and Real-Time PCR to Detect Human Herpes Virus Genome in Ocular Fluids of Patients with Uveitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkus, C.L.; Bispo, P.J.M.; Papaliodis, G.N.; Sobrin, L. Real-time multiplex PCR analysis in infectious uveitis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 34, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, S.; Takase, H.; Nakano, S. Practical use of multiplex and broad-range PCR in ophthalmology. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 65, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichinger, A.; Hagen, A.; Meyer-Bühn, M.; Huebner, J. Clinical Benefits of Introducing Real-Time Multiplex PCR for Cerebrospinal Fluid as Routine Diagnostic at a Tertiary Care Pediatric Center. Infection 2019, 47, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javali, M.; Acharya, P.; Mehta, A.; John, A.A.; Mahale, R.; Srinivasa, R. Use of Multiplex PCR Based Molecular Diagnostics in Diagnosis of Suspected CNS Infections in Tertiary Care Setting—A Retrospective Study. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2017, 161, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailleaux, M.; Pilmis, B.; Mizrahi, A.; Lourtet-Hascoet, J.; Nguyen Van, J.-C.; Alix, L.; Couzigou, C.; Vidal, B.; Tattevin, P.; Le Monnier, A. Impact of a Multiplex PCR Assay (FilmArray®) on the Management of Patients with Suspected Central Nervous System Infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davson, H. A Comparative Study of the Aqueous Humour and Cerebrospinal Fluid in the Rabbit. J. Physiol. 1955, 129, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaichi, N.; Matoba, H.; Ohno, S. The Positive Role of Lumbar Puncture in the Diagnosis of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease: Lymphocyte Subsets in the Aqueous Humor and Cerebrospinal Fluid. Int. Ophthalmol. 2007, 27, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-N.; Cho, M.-C.; Yoo, W.-S.; Kim, R.-B.; Chung, J.-K.; Kim, S.-J. Clinical Results and Utility of Herpesviruses Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction: Assessment of Aqueous Humor Samples from Patients with Corneal Endotheliitis and High Intraocular Pressure. J. Glaucoma 2018, 27, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusko, B.; Thorne, J.; Jabs, D.; Belfort, R.; Dick, A.; Gangaputra, S.; Nussenblatt, R.; Okada, A.; Rosenbaum, J. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Project. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Project: Development of a Clinical Evidence Base Utilizing Informatics Tools and Techniques. Methods Inf. Med. 2013, 52, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, D.A.; Acharya, N.R.; Caspers, L.; Chee, S.-P.; Goldstein, D.; McCluskey, P.; Murray, P.I.; Oden, N.; Palestine, A.G.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; et al. Classification Criteria for Herpes Simplex Virus Anterior Uveitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 228, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, D.A.; Caspers, L.; Chee, S.-P.; Galor, A.; Goldstein, D.; McCluskey, P.; Murray, P.I.; Oden, N.; Palestine, A.G.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; et al. Classification Criteria for Cytomegalovirus Anterior Uveitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 228, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, D.A.; Acharya, N.R.; Caspers, L.; Chee, S.-P.; Goldstein, D.; McCluskey, P.; Murray, P.I.; Oden, N.; Palestine, A.G.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; et al. Classification Criteria for Varicella Zoster Virus Anterior Uveitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 228, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, D.A.; Belfort, R.; Bodaghi, B.; Graham, E.; Holland, G.N.; Lightman, S.L.; Margolis, T.P.; Oden, N.; Palestine, A.G.; Smith, J.R.; et al. Classification Criteria for Acute Retinal Necrosis Syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 228, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P. Infectious Uveitis. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2015, 3, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelcorn, E.D. Infectious Causes of Posterior Uveitis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 48, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabs, D.A.; Belfort, R.; Bodaghi, B.; Graham, E.; Holland, G.N.; Lightman, S.L.; Oden, N.; Palestine, A.G.; Smith, J.R.; Thorne, J.E.; et al. Classification Criteria for Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 228, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.C. Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Aqueous Humour Samples in Necrotising Retinitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, M.A.; Lecuona, K.A.; Rogers, G.; Bunce, C.; Corcoran, C.; Michaelides, M. The Value of Routine Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Intraocular Fluid Specimens in the Diagnosis of Infectious Posterior Uveitis. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 545149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Kwon, K.C.; Park, J.W.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.Y.; Koo, S.H. Evaluation of the Seeplex® Meningitis ACE Detection Kit for the Detection of 12 Common Bacterial and Viral Pathogens of Acute Meningitis. Ann. Lab. Med. 2012, 32, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Marín, J.; Marin, S.; Bernal-Casas, D.; Lillo, A.; González-Subías, M.; Navarro, G.; Cascante, M.; Sánchez-Navés, J.; Franco, R. A Metabolomics Study in Aqueous Humor Discloses Altered Arginine Metabolism in Parkinson’s Disease. Fluids Barriers CNS 2023, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-T.; Kuo, M.-T.; Chiang, W.-Y.; Chao, T.-L.; Kuo, H.-K. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Viral Anterior Uveitis in Southern Taiwan—Diagnosis with Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.-S.; Kim, G.-N.; Chung, I.; Cho, M.-C.; Han, Y.S.; Kang, S.S.; Yun, S.P.; Seo, S.-W.; Kim, S.-J. Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Factors in Hypertensive Anterior Uveitis Diagnosed with Polymerase Chain Reaction. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronopoulos, A.; Roquelaure, D.; Souteyrand, G.; Seebach, J.D.; Schutz, J.S.; Thumann, G. Aqueous Humor Polymerase Chain Reaction in Uveitis—Utility and Safety. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, T.W.; Miller, D.; Schiffman, J.C.; Davis, J.L. Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Aqueous and Vitreous Specimens in the Diagnosis of Posterior Segment Infectious Uveitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 147, 140–147.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.I. Epstein–Barr Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E.T.; Zierhut, M. Epstein-Barr Virus and the Eye. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2020, 28, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, D.; Meyer, D.; Maritz, J.; De Groot-Mijnes, J.D.F. Polymerase Chain Reaction and Goldmann-Witmer Coefficient to Examine the Role of Epstein-Barr Virus in Uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2019, 27, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paor, M.; O’Brien, K.; Fahey, T.; Smith, S.M. Antiviral Agents for Infectious Mononucleosis (Glandular Fever). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD011487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, W.; Sheng, Y. Human herpesvirus 6A infection-associated acute anterior uveitis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 11577–11585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keorochana, N.; Intaraprasong, W.; Choontanom, R. Herpesviridae prevalence in aqueous humor using PCR. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 1707–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group I | Group II | Group III | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 61 (70.1) | 16 (18.6) | 9 (10.3) | - |

| Age a (years) | 54.0 ± 17.2 | 63.4 ± 16.7 | 62.1 ± 13.3 | 0.085 |

| Male:Female | 44:17 | 3:13 | 8:1 | <0.001 |

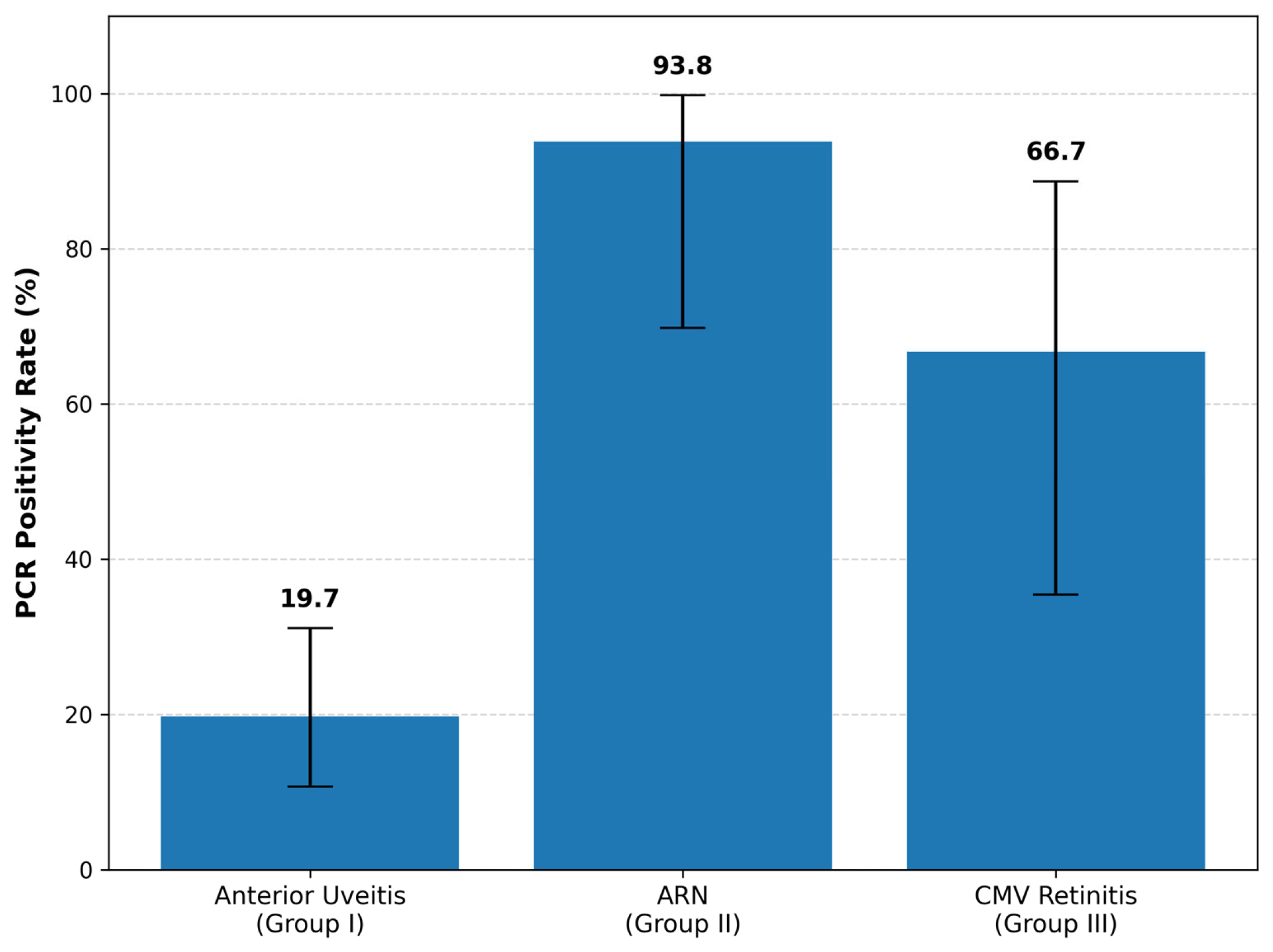

| PCR positive rate | 19.7% (12/61) | 93.8% (15/16) | 66.7% (6/9) | <0.001 |

| Most common pathogen | CMV (66.7%) | VZV (80.0%) | CMV (100.0%) | - |

| Group I | Group II | Group III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMV | 8 | 1 | 6 |

| HHV-6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VZV | 2 | 12 | 0 |

| HSV-1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HSV-2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| EBV | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diagnostic positivity | 12/61 (19.7%) | 15/16 (93.8%) | 6/9 (66.7%) |

| PCR-Positive | PCR-Negative | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 12 | 49 | |

| Age a (years) | 55.8 ± 14.9 | 53.5 ± 17.7 | 0.828 |

| Male:Female | 10:2 | 34:15 | 0.338 |

| Prior topical corticosteroid use | 9 (75.0%) | 25 (51.0%) | 0.186 |

| KPs | 9 (75%) | 29 (59.2%) | 0.315 |

| IOP (mmHg) | 32.0 ± 13.5 | 29.0 ± 13.4 | 0.457 |

| Anti-glaucoma medication history | 10 (83.3%) | 38 (77.6%) | 0.664 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jeong, Y.H.; Park, S.H.; Lee, S.M.; Byon, I.; Yi, J.; Park, S.-W. The Use of CSF Multiplex PCR Panel in Patients with Viral Uveitis. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010143

Jeong YH, Park SH, Lee SM, Byon I, Yi J, Park S-W. The Use of CSF Multiplex PCR Panel in Patients with Viral Uveitis. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Young Hwan, Su Hwan Park, Seung Min Lee, Iksoo Byon, Jongyoun Yi, and Sung-Who Park. 2026. "The Use of CSF Multiplex PCR Panel in Patients with Viral Uveitis" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010143

APA StyleJeong, Y. H., Park, S. H., Lee, S. M., Byon, I., Yi, J., & Park, S.-W. (2026). The Use of CSF Multiplex PCR Panel in Patients with Viral Uveitis. Diagnostics, 16(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010143